Abstract

MRI는 골수의 평가에 있어 가장 예민도가 높은 검사로서 골수 질환의 진단에 있어 매우 중요한 역할을 한다. 그러나, 소아 영상을 자주 접하지 않는 영상의학과 의사들에게는 종종 정상 골수와 병적 골수의 구분이 어려울 수 있고, 소아의 흔한 악성질환인 백혈병이나 신경모세포종의 전이 등 골수를 침범하는 질환들이 임상적으로 다양한 근골격계 증상으로 발현하여 근골격 MRI 검사를 통해 진단되기도 한다. 소아에서 시행되는 MRI를 정확하게 판독하려면 골수의 정상 구성 성분에 대한 이해뿐만 아니라 나이에 따른 골수의 변화(age-related developmental change)와 소아에서 흔하게 골수를 침범하는 질환들에 대한 이해가 중요하다. 본 종설에서는 정상 골수의 구성과 소아 골수의 정상 및 비정상 MRI 소견을 기술하고 백혈병, 신경모세포종의 전이 등의 악성 골수 질환을 중심으로 임상 증례들을 고찰하고자 한다.

Keywords: Bone Marrow, MRI, Children, Leukemia, Neuroblastoma

Abstract

MRI plays a crucial role in bone marrow (BM) assessment, and has very high sensitivity in diagnosing marrow disorders. However, for radiologists who may not frequently encounter pediatric imaging, distinguishing pathologic BM lesion from normal BM can be challenging. Conditions involving the BM in pediatric patients, such as leukemia and metastatic neuroblastoma, often manifest with diverse musculoskeletal symptoms and may be diagnosed using musculoskeletal MRI examinations. Accurate interpretation of pediatric MRI requires not only an understanding of the normal composition of BM but also an awareness of agerelated developmental changes in the marrow and familiarity with conditions that commonly involve pediatric BM. We aim to describe the composition of normal BM and outline the normal and abnormal MRI findings in pediatric BM. Additionally, we aim to present clinical cases of malignant BM disorders including leukemia, neuroblastoma metastasis, and other malignant BM disorders.

서론

골수는 매우 역동적인 변화를 하는 장기이고 모든 자기공명영상(이하 MRI) 검사에서 포함되는 장기로서 소아에서 시행되는 MR 영상검사를 정확하게 판독하려면 골수의 정상 구성 성분에 대한 이해뿐만 아니라 나이에 따른 골수의 변화(age-related developmental change)와 소아에서 흔하게 골수를 침범하는 질환들에 대한 이해가 중요하다. 유아기의 정상 적색 골수는 상대적으로 세포밀집도가 높고 지방이 적으며(1), 성장에 따른 정상 골수의 전환이 성인에 비해 빠르게 진행되어 소아 영상을 자주 접하지 않는 영상의학과 의사들에게는 종종 정상 골수와 병적 골수의 구분이 어려울 수 있다. 또한 소아의 흔한 악성질환인 백혈병이나 신경모세포종의 전이 등 골수를 침범하는 질환들에 이환된 환아들은 임상적으로 다양한 근골격계 증상이 발현하여 내원할 수 있다. 임상적으로 이들 질환을 미처 의심하지 못한 상태에서 증상에 따른 근골격계 MR 영상을 시행하여 골수의 이상이 확인되기도 한다. 본 종설에서는 정상 골수의 구성과 소아 골수의 정상 및 비정상 MRI 소견을 기술하고 백혈병, 신경모세포종의 전이 등의 악성 골수 질환을 중심으로 임상 증례들을 고찰하고자 한다.

정상 골수

뼈는 피질골과 해면골로 구성되어 있으며 해면골 사이에 존재하는 골수는 전체 체중의 약 5% 정도를 차지한다(2). 정상 골수는 조혈작용이 활발한 적색 골수(red marrow)와 그렇지 않은 황색 골수(yellow marrow)로 나누어진다. 적색 골수는 물 40%, 단백질 20%, 지방세포 40%로 구성되며, 황색 골수는 지방세포가 80%, 물 및 비지방세포가 20%를 차지한다(1,3,4). 따라서 지방은 양쪽 골수에서 모두 주요한 구성 성분으로, 지방세포는 단순 저장 조직으로서의 역할뿐만 아니라 대사 및 내분비 등에도 관여하는 것으로 알려져 있다(5). 적색 골수의 성분은 나이에 따라 변화되어 연령이 증가할수록 지방은 증가하고 세포밀집도는 감소된다. 특히 어린 유아기의 정상 적색 골수는 상대적으로 세포밀집도가 높고 지방이 적다(1).

태아의 모든 골수는 적색 골수로 이루어져 있으나 출생 직후부터 점차적으로 황색 골수로 전환되며 이 두 가지 형의 골수는 역동적인 조절 관계에 놓인다. 이러한 생리적 골수의 변화는 특히 소아에서 빠르게 나타나며 이후에는 매우 천천히 진행된다. 적색 골수에서 황색 골수로의 전환(conversion)과 그 반대의 현상인 황색 골수에서 적색 골수로의 재전환(reconversion)은 예측될 수 있는 순서대로 진행되어, 적색 골수에서 황색 골수로의 전환은 사지골의 말단 수족골에서 시작하여 체간골로 진행되는 구심성(centripetal) 진행을 보인다(3). 장골(long bone)에서는 골단(epiphysis) 및 골기(apophysis)에서 시작하여 골간(diaphysis), 그리고 골간단(metaphysis) 순으로 진행된다(Fig. 1) (4,6).

Fig. 1. Age-related marrow conversion in long bones.

During the perinatal period, a secondary ossification center appears in the epiphysis/apophysis, where the red marrow is rapidly converted to yellow marrow within 6 months. Secondary ossification centers (arrowheads) with yellow marrow signals are prominently noted at either end of the long bones throughout childhood. During adolescence, marrow conversion begins at the central portion of the diaphysis (*) and spreads bidirectionally towards either end of the metaphysis. Conversion occurs until the late 3rd decade of life when most of the marrow is yellow marrow, with a small amount of red marrow (arrow) remaining in the proximal portion of the metaphysis.

황색 골수에서 적색 골수로의 재전환(reconversion)은 조혈증가가 요구되는 다양한 상황에서 전환의 역방향, 즉 체간골에서 먼저, 그 후에 사지골에서 적색 골수의 증가가 일어나게 되며, 재전환의 범위는 조혈이 요구되는 자극의 정도나 기간에 의해 결정된다(4,7). 골수의 변화는 골수 내의 온도 변화, 혈액 분포나 산소압에 의해서도 영향을 받게 되어 만성 빈혈, 흡연, 높은 고도, 청색 증형 심장병, 장거리 달리기 등에서 골수의 재전환이 증가한다(7,8,9,10). 골수의 전환은 대부분 25세 정도에 이르면 완성되어 성인 골수의 형태를 보이게 되며 이 시기에는 적색 골수가 체간골과 대퇴골 및 상완골의 근위부 골간단에만 남아있게 된다(3,4,8,11).

성인에서 척추 골수의 전환은 40세 정도에 척추체정맥얼기(basivertebral venous plexus)에서 시작하여 끝판(endplate) 쪽으로 서서히 진행하게 된다(12,13).

골수의 MR 영상기법 및 소견

MR 영상은 골수의 비침습적 평가에 있어 가장 예민한 진단 방법이며 사용되는 영상기법과 골수 내의 물과 지방의 상대적 비율, 환자의 나이 등에 따라 다양하게 보일 수 있다. 여러 영상기법 중 가장 기본적인 스핀에코기법 중에서 골수의 주성분인 지방을 잘 보여주는 것은 T1 강조영상이다.

T1 강조영상

지방은 짧은 T1 이완시간으로 인해 T1 강조영상에서 고신호강도를 보이게 되며, 따라서 황색 골수는 피하지방과 거의 비슷하거나 약간 낮은 정도의 균질한 고신호강도를 보여준다(Fig. 2) (14). 상대적으로 지방이 적고 T1 이완시간이 긴 물의 함량이 높은 적색 골수는 T1 강조 영상에서 피하지방보다는 낮은 신호를 보이면서 근육이나 추간판 디스크보다는 높은 중등도 신호강도를 보인다(9).

Fig. 2. T1-weighted images of normal marrow conversion of the femur according to age.

A. At 3 months, the marrow is composed of red marrow with an intermediate T1 signal.

B. At 6 months, the epiphysis (arrows) shows yellow marrow conversion with a T1 high signal.

C. During childhood, marrow conversion starts at the center of the diaphysis (arrows), which spreads bidirectionally to either end of the long bone.

D. During adolescence, a heterogeneous T1 signal is noted at the proximal metaphysis (arrows) because of the remaining red marrow.

척추검사시 시상면 (sagittal) T1 강조영상이 골수 평가에 가장 유용하며(Fig. 3) 고관절 검사시에는 관상면(coronal) T1 강조영상이, 그 외 관절을 포함한 검사에는 시상면 또는 관상면 T1 강조영상이 가장 유용하므로 해당 부위 검사시 반드시 포함되어야 한다.

Fig. 3. T1-weighted images of normal spinal marrow maturation.

A-D. Sagittal T1-weighted images of the vertebrae at (A) 3 days, (B) 7 months, (C) 3 years, and (D) 11 years of age. (A) Oval-shaped vertebral body ossification centers (*) are primarily composed of red marrow, and are hypointense compared to the cartilaginous endplates (arrowheads) and intervertebral discs (arrows). (B) Vertebral body ossification centers (*) appear to be isointense compared to intervertebral discs (arrows). (C) Vertebral bodies (*) appear slightly hyperintense compared to the intervertebral disc, especially around the basivertebral vein (curved arrow). (D) The signal intensity of the vertebral body (*) becomes higher than that of the intervertebral disc.

병적 골수는 정상 골수에 비해 물의 함량이 증가하고 지방조직을 대체하면서 T1 강조영상에서 저신호강도를 보이므로, 골수의 신호강도가 T1 강조영상에서 근육이나 추간판보다 비슷하거나 낮은 신호강도를 보이면 일단 병적골수의 가능성을 의심하여야 한다(Fig. 4) (7,12).

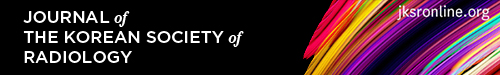

Fig. 4. Normal versus abnormal marrow of two 2-year-old children on T1-weighted image of hip MRI.

A. Coronal T1-weighted image of the hip in a patient with right hip synovitis shows normal signal intensity of yellow and red marrow in the femur, pelvic bones, and vertebrae.

B. Coronal T1-weighted image of the hip in a patient with metastatic neuroblastoma shows diffusely isointense marrow signals at the femurs, pelvic bones, and vertebrae compared to the muscles, which is abnormal considering the extent of marrow conversion seen in a normal 2-year-old.

T2 강조영상 및 Fat Suppression/Short Tau Inversion Recovery

T2 강조영상은 적색 및 황색 골수의 신호강도 차이가 감소하여 골수의 평가에는 제한적이며 이를 대체하는 영상기법으로서 지방억제(fat-saturated) 고속스핀에코(fast spin echo; 이하 FSE), short tau inversion recovery (이하 STIR) 기법이 유용하다. STIR 기법을 통한 지방억제는 fat-saturated FSE에 비해 자장의 불균질성이나 motion artifact에 영향을 덜 받는다는 장점이 있다(9).

Fat-saturated FSE 및 STIR 영상에서 정상 적색 골수는 근육보다 약간 높은 정도의 중등도(intermediate) 신호강도를 보이나 병적 골수는 정상 골수보다 훨씬 높은 고신호강도를 보임으로써 병변의 대조도가 증가된다(Fig. 5, Table 1) (7,14). T1 강조영상에서처럼 골수 평가 시에는 관상면 또는 시상면의 STIR 또는 fat-saturated T2 FSE 영상을 포함하여야 한다.

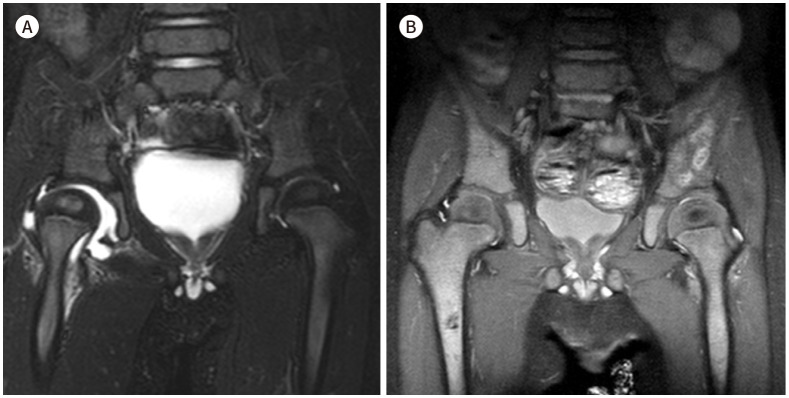

Fig. 5. Normal versus abnormal marrow of two 2-year-old children on fat saturated T2 weighted image of hip MRI.

A. Coronal fat saturated T2-weighted image of the hip in a patient with right hip synovitis shows intermediate signal intensity of normal marrow, slightly higher than that of the skeletal muscles.

B. Coronal fat saturated T2-weighted image of the hip in a patient with metastatic neuroblastoma shows diffusely abnormal high signal intensity of the marrow due to marrow metastasis.

Table 1. Comparison of Signal Intensities of Red, Yellow, and Pathologic Marrow in MRI Sequences with that of Muscle or Intervertebral Disc.

| T1WI | T2WI | FS T2WI or STIR | Chemical Shift | Enhancement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red marrow | Intermediate* | Intermediate | Intermediate | Signal drop in opposed phase | Present |

| Yellow marrow | High | High | Low | Signal drop in opposed phase | No |

| Pathologic marrow | Low | High | High | No signal drop in opposed phase | Present |

*Higher signal intensity compared to muscle or intervertebral disc in children > 1 year old, but may be lower in children < 1 year old.

FS = fat-saturation, STIR = short tau inversion recovery, T1WI = T1-weighted image, T2WI = T2-weighted image

많이 쓰이고 있는 또 다른 지방억제의 기법으로는 Dixon 기법이 있는데, 물과 지방의 양성자(proton)의 공명주파수의 차이에 기초한 화학적 이동을 이용한 지방-물 분리(chemical shift-based fat-water separation) 기법으로 지방과 물 양성자의 동위상(in phase)과 역위상(out of phase)을 얻어 역위상에의 신호 소실 여부로 지방의 존재를 평가한다(15). 균일한 지방억제와 함께 지방의 정량적 평가가 가능하다는 장점으로 골수 질환의 평가 시에 특히 유용한 기법이다(16,17,18).

조영증강 T1 강조영상

조영증강 영상에서 병적 골수는 조영증강을 보인다. 그러나 적색 골수도 정상적으로 조영증강을 보이며 특히 나이가 어릴수록 골수의 혈관분포가 풍부하고 세포밀집도가 높아 성인에 비해 조영증강이 잘 된다(3,7). 또한 이 시기에는 적색 골수가 상대적으로 지방이 적고 높은 세포밀집도로 인해 T1 강조영상에서 근육과 비슷하거나 좀 더 낮은 신호강도를 보이므로 병적 골수와 구분이 어려울 수 있어 주의가 요구된다(7).

소아의 악성 골수 질환

급성백혈병

급성백혈병은 소아에서 가장 흔한 악성질환으로 급성 림프구성 백혈병(acute lymphoblastic leukemia)이 가장 흔한 아형이다. MRI에서 백혈병에 의한 골수의 침윤은 미만성 및 국소성 양상으로 나누어진다(19). 이 중 미만성 침윤이 가장 흔하며 T1 강조영상에서 정상 황색 골수의 고신호 강도가 균질하게 소실되고 지방억제 T2 강조영상에서는 균질하게 고신호강도를 보이는 “flipflop” sign을 보인다(Figs. 6, 7) (20,21). 말초혈액에서 모세포가 발견되지 않는 무백혈성 백혈병(aleukemic leukemia)의 경우 MRI에서 확인되는 골수의 침윤 분포가 골수 검사의 위치를 결정하는데 있어 매우 중요한 역할을 한다(Fig. 8) (21).

Fig. 6. Spine MRI in a 17-year-old leukemia patient who presented with back pain.

A. T1-weighted image shows a slightly lower marrow signal of the vertebrae compared to that of the intervertebral disc.

B. On T2-weighted image, the marrow shows a diffusely higher signal intensity than that of normal marrow.

C. Postcontrast fat-saturated T1-weighted image shows homogeneous enhancement of the vertebrae.

Fig. 7. Thigh MRI of a 10-year-old patient who presented with right thigh swelling and pain.

A. Axial T2 short tau inversion recovery image shows intramuscular abscess cavity in right rectus femoris along with myositis and cellulitis, and an abnormally high marrow signal of the femur (arrow).

B. Diffusely low marrow signal on T1-weighted image is noted in the femurs and pelvic bones, indicating diffuse infiltrative marrow disease. Following MRI examination, the patient underwent incision and drainage of the thigh with antibiotics treatment, and the abscess was resolved. However, detection of abnormal marrow signal was missed during initial MRI interpretation, and after prolonged cytopenia, the patient was diagnosed with leukemia with bone marrow biopsy 2 weeks after MRI.

Fig. 8. A 5-year-old boy with recurrent fever and left shoulder pain, who was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

A. T1-weighted sagittal image shows abnormal low signal intensity of the marrow in the humerus.

B, C. Fat saturated coronal T2-weighted image (B) shows heterogenously increased marrow signals of the scapula, clavicle and humerus, with (C) heterogeneous enhancement in fat-saturated postcontrast T1-weighted image. Peripheral blood was unremarkable without blasts, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis was suspected clinically. However, due to prolonged fever for one month, the patient underwent bone marrow biopsy and was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

악성세포의 골수 침윤에 의한 미세혈관 폐색으로 인해 골수괴사(marrow necrosis)나 골괴사(osteonecrosis or bone infarction)가 이차적으로 생길 수 있으며, 이는 급성 림프구성 백혈병 환자의 6.5%–15%에서 보고된다(22,23). 이러한 골수 또는 골괴사가 뼈의 통증을 일으킬 수 있고 급성기에는 테두리 조영증강(peripheral rim-like enhancement)을 보여 골농양으로 오인될 수 있다(24). 이러한 골수괴사는 백혈병뿐만 아니라 신경모세포종을 포함한 다른 악성질환의 골수 전이에서도 보일 수 있는 소견으로, 전반적인 골수의 신호강도를 주의 깊게 관찰하여 기저 골수의 침윤성 질환 유무를 평가하여야 한다(Fig. 9). 백혈병 환자에서 경미한 외상으로 인해 병적 골절이 발생할 수도 있는데, 외상과 관련하여 시행한 근골격 영상에서 골수의 이상 유무를 항상 확인하여 진단을 놓치거나 지체하지 않도록 하여야 한다(Fig. 10) (25,26).

Fig. 9. A 3-year-old girl presented with right thigh pain, who was diagnosed with metastatic neuroblastoma.

A, B. T1-weighted (A) and fat-saturated T2-weighted (B) images of both thighs show diffusely abnormal marrow signals of the femurs and pelvic bones, representing diffuse infiltrative marrow disease.

C. In the postcontrast fat-saturated T1-weighted image, the right femoral shaft shows a lesion (arrowhead) with peripheral rim enhancement, which is considered to be marrow necrosis.

D. Abdominal CT reveals a small left adrenal tumor (arrow), which was surgically confirmed as neuroblastoma.

Fig. 10. Pathologic fracture triggered by jumping rope in a 15-year-old girl who was diagnosed with B-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia.

A, B. Sagittal T1- (A) and fat-saturated T2-weighted (B) images show cortical discontinuity along with marrow signal change (arrows) at the medial cuneiform. Note another nodular marrow lesion (arrowheads) with low T1 and high T2 signals. Conservative treatment was done, and further evaluation was not done at that time. One and a half month later, the patient presented with azotemia.

C. Renal ultrasonography shows marked globular enlargement with multiple scattered hypoechoic lesions at the cortex. Kidney biopsy confirmed B-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia.

D. Note multifocal FDG uptake of lower leg bones/marrow in 18F-FDG PET.

FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose

신경모세종의 골수 전이

신경모세포종(neuroblastoma)은 소아의 두개외 종양 중 가장 흔한 고형암으로 주로 2–5세에서 발생하며 환자의 약 반수에서 진단 시 이미 골수나 뼈, 림프절 등에 원격전이를 동반한다(27). 신경모세포종 환자들은 뼈나 관절 통증으로 인해 초기에 고관절, 무릎 또는 척추 등의 MR 영상검사를 하여 골수나 골전이가 먼저 발견되고 이후 원발 부위 종양이 진단되는 경우가 적지 않다(28,29). 신경모세포종의 골수 전이의 MRI 소견은 백혈병과 비슷하나 미만성 침윤보다는 다발성의 국소성 침윤이 더 흔하다. 골수나 골괴사도 동반되어 그 부위에 통증을 호소하기도 하는데 임상적으로 발열 및 혈액검사 상 염증수치 증가가 동반되어 골수염으로 오진되는 경우가 흔하다(Fig. 11) (29,30,31). 백혈병에서와 마찬가지로 전반적인 골수의 이상 유무를 잘 파악하여 진단의 오류를 범하지 않도록 하여야 한다. 복부나 골반강이 같이 스캔된 경우 후복막강에 원발병소가 함께 확인되거나 다른 전이 병변을 추가적으로 확인할 수 있다(Fig. 12) (29,32).

Fig. 11. A 2-year-old boy with fever and limping, who was diagnosed with metastatic neuroblastoma.

A. On plain radiograph, permeative osteolysis is noted, with cortical destruction in distal tibial shaft.

B, C. Coronal T1-weighted image (B) shows abnormal low signal of the marrow of the tibia, with (C) increased signal in sagittal fat-saturated T2-weighted image.

D. After gadolinium injection, heterogeneous enhancement of the marrow is noted with bone/bone marrow infarction in the distal tibia (arrowhead).

E. Abdominal CT taken 2 months later reveals left adrenal neuroblastoma (arrow) with multiple bone metastasis (not shown here).

Fig. 12. A 5-year-old boy with back pain, who was diagnosed with metastatic neuroblastoma.

A, B. Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and fat-saturated postcontrast T1-weighted (B) images show a diffusely abnormal marrow signal (low T1 signal with increased enhancement) of the spine as well as an epidural mass (arrows) with a non-enhancing bone lesion at L1 (arrowhead).

C, D. In the axial view, the primary tumor is conspicuous in the left paravertebral area (arrows) on both T2-weighted (C) and fat-saturated postcontrast T1-weighted (D) images, which was confirmed as neuroblastoma. The peripheral enhancing marrow/bone lesion in L1 (arrowheads) represents bone/marrow infarction in the underlying diffuse marrow metastasis.

림프종

골 및 골수의 침범은 호지킨 림프종(Hodgkin lymphoma)보다 비호지킨 림프종(non-Hodgkin lymphoma)에서 좀 더 흔하며 골 및 골수를 직접 침범하거나 전이로 인한 골수 침범을 보이기도 한다(21,23,33). 국소 병변으로 주로 보이나 드물게 미만성으로 침범도 확인된다(Fig. 13) (13,20).

Fig. 13. A 14-year-old boy with lymphoma, who presented with lower extremity weakness.

A-C. Sagittal T1-weighted (A), T2-weighted (B), and fat-saturated postcontrast T1-weighted (C) images show diffuse abnormal marrow infiltration of the vertebrae with marrow necrosis, most prominent in the T2 vertebral body (black arrowhead). Note the large enhancing cervical mass (arrows) extending to the prevertebral space and multiple epidural enhancing lesions (white arrowheads). Biopsy of the neck mass revealed lymphoma, which was accompanied by epidural and marrow metastases.

그 외 악성 종양 및 골수 전이

신경모세포종 외에도 소아에서 흔한 원발성 악성 골종양인 골육종(osteosarcoma)과 유잉 육종(Ewing sarcoma)의 경우 골 및 골수를 직접 침범하고 혈행성 전이를 통해 다른 부위의 골수로 퍼질 수 있다(34). 연부조직 종양인 횡문근육종(rhabdomyosarcoma) 등도 골수로 전이될 수 있으며 이들은 주로 혈행성 전이를 하게 되므로 혈관이 풍부한 적색 골수에 다발성의 국소 병변을 형성한다(Fig. 14) (35). 골수의 전이는 뼈의 전이 평가를 위해 시행하는 핵의학 검사에서는 잘 나타나지 않으며 골수 전이 여부는 MRI가 가장 예민한 진단 방법이다(23,36).

Fig. 14. A 14-year-old girl diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma with diffuse bone marrow metastasis.

A-C. Coronal T1-weighted image (A), STIR (B), and fat suppressed postcontrast T1-weighted (C) images show an irregularly enhancing mass from the left perineum to the left pelvic sidewall (white arrowheads) and another mass in the left lower retroperitoneal space (black arrowheads). Biopsy of the inguinal lymph nodes (not shown here) revealed alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. On T1-weighted image (A), the marrow signals of the humeri, vertebrae, and femurs are diffusely low. On STIR (B), the bone marrow signal in the entire skeleton is heterogeneously increased, (C) with heterogeneous enhancement, suggesting extensive marrow metastasis.

STIR = short tau inversion recovery

함정(Pitfalls)

골수 병변이 국소적으로 있는 경우에는 영상에서 비교적 쉽게 찾을 수 있으나 백혈병 등에서 미만성으로 균질하게 골수를 침범한 경우 병적 골수를 간과할 수 있으므로 판독 시 주의하여야 한다. 때로 신호강도만으로는 국소성 적색 골수와 병적 골수의 감별이 어려울 수 있는데, 적색 골수는 대개 경계가 불분명하거나 부드러운 경계를 보이면서 황색 골수와 상호 교차되는(interdigitation) 양상으로 비교적 대칭적으로 보이는 반면, 병적 골수는 경계가 분명하면서 좀 더 둥근 모양으로 보인다(3). 성장기의 소아에서는 잔존하는 적색 골수로 인해 정상 골수가 다소 비균질하게 보일 수 있으며 특히 청소년기에 장골의 성장판이 닫히면서 그 주위 골간단과 골단에 국소적으로 불꽃모양(flame-shaped)의 골수 부종(focal periphyseal edema 또는 FOPE)이 보일 수 있는데 이는 성장판 융합(fusion)에 따른 정상 과정으로 알려져 있다(Fig. 15) (4,37). 족부 골수의 적색 골수가 국소적으로 남아있거나 운동 제한(immobilization)이나 생리학적 스트레스 등으로 황색 골수에서 적색 골수로 재전환시 경계가 불분명한 T2 고신호강도의 국소병변으로 보이기도 하는데 이들도 병적 골수로 오인하지 않도록 주의가 필요하다(Fig. 16) (37,38).

Fig. 15. Focal periphyseal edema in a 14-year-old girl who presented with knee pain.

A. Sagittal fat suppressed T2-weighted image shows flame-shaped edema-like high signal intensity lesion (arrows) in the metaphysis and epiphysis of the distal femur, centered at the physis.

B. On coronal T1-weighted image, the flame shaped lesion (arrows) shows an intermediate signal.

Fig. 16. Normal hematopoietic foci in a child’s foot.

A, B. T1-weighted (A) and fat-saturated T2-weighted (B) images show multiple ill-defined nodular marrow lesions with intermediate signals in the talus and calcaneus, representing normal hematopoietic foci. A small amount of effusion is observed in the talofibular joints.

결론

MRI는 골수 질환의 평가에 있어 비침습적이면서 매우 예민도가 높은 검사로서, 정확한 판독을 위해서는 정상 골수의 구성과 나이에 따른 골수의 변화에 대한 이해와 골수 평가를 위한 적절한 영상기법과 정상 및 병적 골수의 영상 소견 그리고 병변으로 오인될 수 있는 정상 변이들을 숙지하여야 한다. 특히 소아에서 시행되는 MRI는 어느 부위에서 검사가 시행되었든 상관없이 항상 골수에 주의를 기울여서 백혈병이나 전이성 신경모세종과 같은 악성질환의 진단을 놓치지 않도록 하여야 한다.

Footnotes

- Conceptualization, Y.S.

- data curation, all authors.

- investigation, Y.S.

- supervision, Y.S., K.J.H.

- visualization, Y.A., J.T.Y., P.J.

- writing—original draft, Y.A., J.T.Y.

- writing—review & editing, Y.A., Y.S., P.J., K.J.H.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: None

Supplementary Materials

English translation of this article is available with the Online-only Data Supplement at https://doi.org/10.3348/jksr.2024.0039.

References

- 1.Chiarilli MG, Delli Pizzi A, Mastrodicasa D, Febo MP, Cardinali B, Consorte B, et al. Bone marrow magnetic resonance imaging: physiologic and pathologic findings that radiologist should know. Radiol Med. 2021;126:264–276. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travlos GS. Normal structure, function, and histology of the bone marrow. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:548–565. doi: 10.1080/01926230600939856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan BY, Gill KG, Rebsamen SL, Nguyen JC. MR imaging of pediatric bone marrow. Radiographics. 2016;36:1911–1930. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augusto ACL, Goes PCK, Flores DV, Costa MAF, Takahashi MS, Rodrigues ACO, et al. Imaging review of normal and abnormal skeletal maturation. Radiographics. 2022;42:861–879. doi: 10.1148/rg.210088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Leng Y, Gong Y. Bone marrow fat and hematopoiesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:694. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster K, Chapman S, Johnson K. MRI of the marrow in the paediatric skeleton. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:651–673. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdiles A, Babyn PS. Pediatric bone marrow MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2009;17:391–409. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Małkiewicz A, Dziedzic M. Bone marrow reconversion - imaging of physiological changes in bone marrow. Pol J Radiol. 2012;77:45–50. doi: 10.12659/pjr.883628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang S, Panicek DM. Magnetic resonance imaging of bone marrow in oncology, part 1. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:913–920. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez FM, Mitchell J, Monfred E, Anguh T, Mulligan M. Knee MRI patterns of bone marrow reconversion and relationship to anemia. Acta Radiol. 2016;57:964–970. doi: 10.1177/0284185115610932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aparisi Gómez MP, Ayuso Benavent C, Simoni P, Musa Aguiar P, Bazzocchi A, Aparisi F. Imaging of bone marrow: from science to practice. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2022;26:396–411. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1745803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah LM, Hanrahan CJ. MRI of spinal bone marrow: part I, techniques and normal age-related appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1298–1308. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanrahan CJ, Shah LM. MRI of spinal bone marrow: part 2, T1-weighted imaging-based differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1309–1321. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynes JP, Hughes N, Cunningham P, Kavanagh EC, Eustace SJ. Whole-body MRI of bone marrow: a review. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50:1687–1701. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Vucht N, Santiago R, Lottmann B, Pressney I, Harder D, Sheikh A, et al. The Dixon technique for MRI of the bone marrow. Skeletal Radiol. 2019;48:1861–1874. doi: 10.1007/s00256-019-03271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Grande F, Santini F, Herzka DA, Aro MR, Dean CW, Gold GE, et al. Fat-suppression techniques for 3-T MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiographics. 2014;34:217–233. doi: 10.1148/rg.341135130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winfeld M, Ahlawat S, Safdar N. Utilization of chemical shift MRI in the diagnosis of disorders affecting pediatric bone marrow. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45:1205–1212. doi: 10.1007/s00256-016-2403-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeder Y, Dunet V, Richard R, Becce F, Omoumi P. Bone marrow metastases: T2-weighted Dixon spin-echo fat images can replace T1-weighted spin-echo images. Radiology. 2018;286:948–959. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resnick D, Kang HS, Pretterklieber ML. Internal derangements of joints. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007. pp. 231–257. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen JC, Davis KW, Arkader A, Guariento A, Sze A, Hong S, et al. Pre-treatment MRI of leukaemia and lymphoma in children: are there differences in marrow replacement patterns on T1-weighted images? Eur Radiol. 2021;31:7992–8000. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-07814-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Averill LW, Acikgoz G, Miller RE, Kandula VV, Epelman M. Update on pediatric leukemia and lymphoma imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2013;34:578–599. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vesterby A, Myhre Jensen O. Aseptic bone/bone marrow necrosis in leukaemia. Scand J Haematol. 1985;35:354–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1985.tb01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang S, Panicek DM. Magnetic resonance imaging of bone marrow in oncology, part 2. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:1017–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nies BA, Kundel DW, Thomas LB, Freireich EJ. Leukopenia, bone pain, and bone necrosis in patients with acute leukemia: a clinicopathologic complex. Ann Intern Med. 1965;62:698–705. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-62-4-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tannenbaum MF, Noda S, Cohen S, Rissmiller JG, Golja AM, Schwartz DM. Imaging musculoskeletal manifestations of pediatric hematologic malignancies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:455–464. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saifuddin A, Tyler P, Rajakulasingam R. Imaging of bone marrow pitfalls with emphasis on MRI. Br J Radiol. 2023;96:20220063. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuBois SG, Kalika Y, Lukens JN, Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Atkinson JB, et al. Metastatic sites in stage IV and IVS neuroblastoma correlate with age, tumor biology, and survival. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21:181–189. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parmar R, Wadia F, Yassa R, Zenios M. Neuroblastoma: a rare cause of a limping child. How to avoid a delayed diagnosis? J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33:e45–e51. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318279c636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu CM, Rasalkar DD, Hu YJ, Cheng FW, Li CK, Chu WC. Clinical presentations and imaging findings of neu roblastoma beyond abdominal mass and a review of imaging algorithm. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:81–91. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31861984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirano N, Goto H, Suenobu S, Ihara K. Bone marrow metastasis of neuroblastoma mimicking purulent osteomyelitis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50:1227–1228. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaa046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orr KE, McHugh K. The new international neuroblastoma response criteria. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49:1433–1440. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nour-Eldin NE, Abdelmonem O, Tawfik AM, Naguib NN, Klingebiel T, Rolle U, et al. Pediatric primary and metastatic neuroblastoma: MRI findings: pictorial review. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwee TC, Kwee RM, Verdonck LF, Bierings MB, Nievelstein RA. Magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of bone marrow involvement in malignant lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaste SC. Imaging pediatric bone sarcomas. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:749–765. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JR, Yoon HM, Koh KN, Jung AY, Cho YA, Lee JS. Rhabdomyosarcoma in children and adolescents: patterns and risk factors of distant metastasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:409–416. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taoka T, Mayr NA, Lee HJ, Yuh WT, Simonson TM, Rezai K, et al. Factors influencing visualization of vertebral metastases on MR imaging versus bone scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1525–1530. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Person A, Janitz E, Thapa M. Pediatric bone marrow: normal and abnormal MRI appearance. Semin Roentgenol. 2021;56:325–337. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2021.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter WR, Goldman LH, Rosenberg ZS. Pitfalls in MRI of the developing pediatric ankle. Radiographics. 2021;41:210–223. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.