Abstract

Robotic-assisted bronchoscopy (RAB) was recently added to the armamentarium of tools used in sampling peripheral lung nodules. Protocols and guidelines have since been published advocating use of large oral artificial airways, use of confirmatory technologies such as radial endobronchial ultrasound (R-EBUS), and preferably limiting sampling to pulmonary parenchymal lesions. We present three clinical cases where RAB was used unconventionally to sample pulmonary nodules in unusual locations and in patients with challenging airway anatomy. In case 1, we introduced the ion catheter through a nasal airway in a patient with trismus. In case 2, we established a diagnosis by sampling a station 5 lymph node, and in case 3, we sampled a lesion located behind an airway stump from previous thoracic surgery. All three patients would have presented significant challenges for alternative biopsy modalities such as CT-guided needle biopsy or video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Keywords: biopsy, bronchoscopy, robotic bronchoscopy

Introduction

Robotic-assisted bronchoscopy (RAB) was FDA approved in 2018 and has rapidly gained widespread adoption as an important tool for bronchoscopic sampling of pulmonary nodules. 1 Several advantages have led to the adoption of robotic bronchoscopy in the United States. These include the stability of the system, the ability of the catheter to remain in position without the need of human hands, and the improved navigation platform. 2

At our institution, we use the Ion™ endoluminal RB platform (Intuitive Surgical©, Sunnyvale, USA). The Ion RB (IRB) platform uses a shape-sensing technology to allow bronchoscopic navigation of a 3.5-mm OD catheter with an endoluminal vision probe into the lung periphery while maintaining catheter stability and shape to maximize precision in sampling. 3 After reaching the target, the vision probe is removed to allow biopsy tools to be utilized. The IRB platform incorporates a thin slice CT prior to the procedure that creates a 3D airway tree with anatomical borders and provides a pathway to pulmonary nodules or masses for sampling purposes.1,2,4–8 Combining the system with fluoroscopy and radial endobronchial ultrasound (r-EBUS) improves the diagnostic yield even further.

Several published protocols have strongly recommended the use of general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation using large size (8.0–9.0) endotracheal tubes. These protocols also recommend the delivery of 6–8 mL/kg ideal body weight of tidal volume and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5–10 cm H2O. 9 The use of general anesthesia along with bigger endotracheal tube (ETT) and tidal volumes is thought to provide stable anatomic orientation after registration by minimizing CT-to-body divergence. Furthermore, it allows access for a therapeutic bronchoscope to clear pre-existing secretions and to prevent potential intra-procedural atelectasis, which may interfere with the r-EBUS signal leading to lower diagnostic yield. 9

This case series highlights challenging clinical scenarios, during which shape sensing robotic bronchoscopy was used to sample chest lesions in unusual locations or in cases presenting challenges to the recommended airway access and ventilation protocols.

Case description

The reporting of the following three cases conforms to the CARE checklist. 13

Case 1

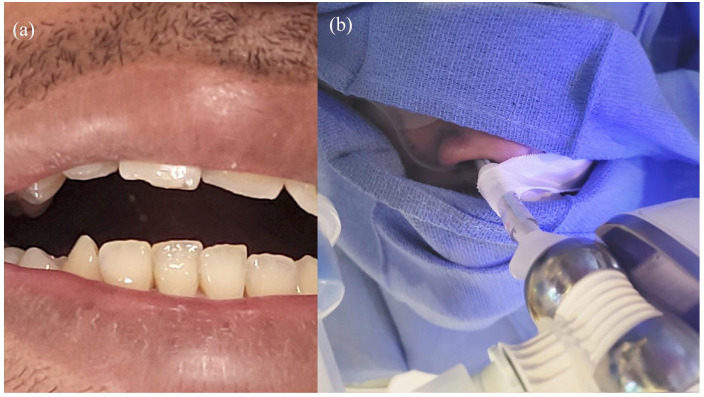

A 32-year-old male, never smoker, with known head and neck cancer status post-resection and adjuvant radiation, presented for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) avid left upper lobe (LUL) pulmonary nodules. The patient had severe trismus [Figure 1(a)], which would potentially inhibit intubation through the oropharynx with a large ETT. A 6.5 cuffed ETT was placed into the right nostril under fiberoptic guidance [Figure 1(b)]. The IRB platform was then docked to the ETT. Navigational guidance was used to reach the LUL nodule up to 0 mm from the edge. Transbronchial needle aspiration was performed using 21- and 19-gauge needles. Transbronchial forceps biopsy with a 1.7-mm forceps, transbronchial brush, and bronchoalveolar lavage were also obtained under fluoroscopic guidance. Rapid onsite evaluation showed scant degenerated cells. Final pathology showed necrotic debris and chronic inflammation, but no malignant cells. Cultures were negative. Follow-up CT scans of the chest were performed at 3, 6, and 12 months showing near complete resolution of his nodules, confirming benign etiology.

Figure 1.

(a) Trismus limiting oral intubation and (b) 6.5 ETT through nare and connected to Ion adapter.

ETT, endotracheal tube.

Case 2

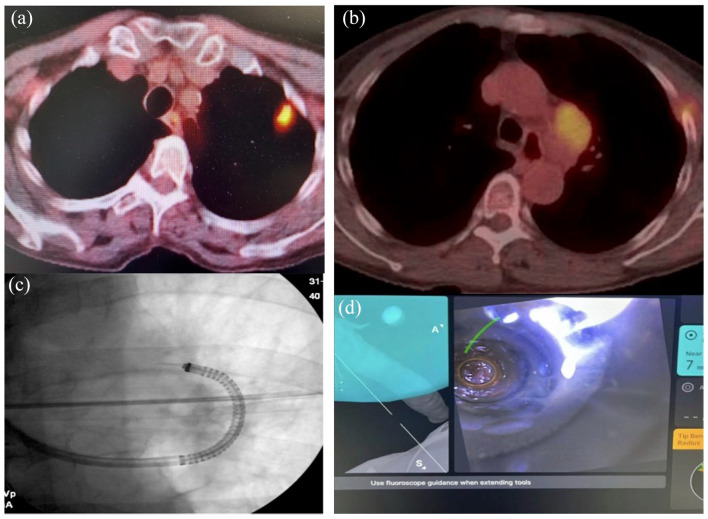

A 67-year-old female with a 60 pack-year smoking history presented with a PET avid LUL nodule and level 5 adenopathy [Figure 2(a) and (b)]. She underwent convex EBUS-TBNA of lymph node stations 4L and 11L. Rapid on-site cytology was negative. The IRB catheter was then advanced to the LUL nodule. Radial-EBUS showed an eccentric view, and multiple TransBronchial Needle Aspiration (TBNA) were obtained using a 21-gauge needle. Rapid-on site cytology did not reveal malignant cells. The catheter was then advanced in the direction of lymph node station 5 under fluoroscopic guidance [Figure 2(c)]. The catheter was parked against an airway wall about 7 mm away from the lymph node [Figure 2(d)]. Multiple TBNA were obtained using a 21-gauge needle. Chest X-ray at the end of the procedure did not show a pneumothorax. Final pathology reports confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic small cell carcinoma from lymph node station 5. All other specimens were non-conclusive on final pathology reports.

Figure 2.

(a) and (b) PET/CT scan showing pet +LUL nodule and station 5 adenopathy. LUL, left upper lobe. (c) and (d) Fluoroscopic image of Ion needle in station 5 and lung window view of lymph node station 5.

PET/CT, Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography.

Case 3

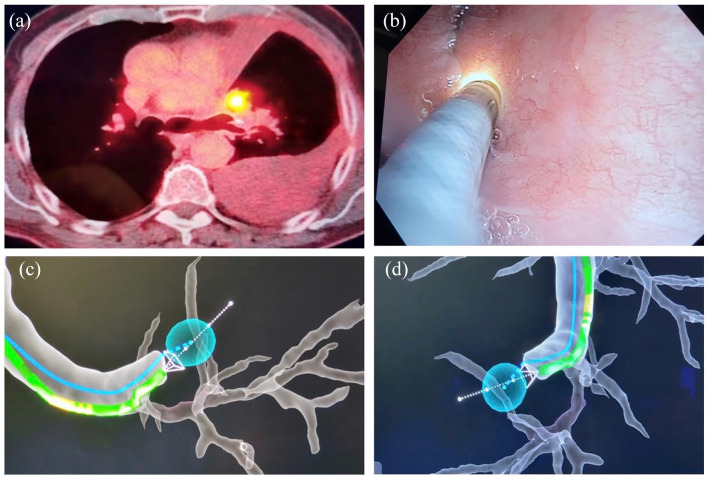

A 71-year-old male with tobacco use and a history of squamous cell lung cancer status post LUL lobectomy presented with a large left pleural effusion and a hypermetabolic mass at the site of the prior left upper lobectomy, indicating tumor recurrence. This mass was located behind the LUL bronchus stump [Figure 3(a)]. Pleural fluid cytology showed no malignant cells. He underwent robotic bronchoscopy. The IRB catheter was parked against the LUL stump [Figure 3(b)–(d)]. A 25-gauge needle was extended through the stump into the mass, which was sampled. Cytology showed recurrent squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 3.

(a) PET + nodule behind LUL bronchus stump. (b) Ion catheter visualized with another bronchoscope view. (c) and (d) Virtual view of PET + nodule behind airway stump.

LUL, left upper lobe.

Discussion

The diagnosis of peripheral lesions is challenging, and no single tool or technology has been associated with 100% diagnostic yield. Robotic bronchoscopy has shown a navigation success of 88.6%, with a 70–77% diagnostic yield, and has been rapidly adopted across the United States. The demand for peripheral bronchoscopy and RAB has increased with the higher incidence of pulmonary nodules seen with the wide adoption of lung cancer screening.10,11

Case 1 featured significant airway access limitation in a patient with trismus and a challenging LUL nodule location, which made the option for CT-guided biopsy unrealistic. Published guidelines advocate for larger artificial airways during RAB to facilitate initial airway clearance with therapeutic bronchoscopes prior to docking the robot.4,6 In this particular case, oral intubation with a large artificial airway was not possible. Although not optimal, initial airway clearance was performed using a small bronchoscope through a 6.5 ETT prior to performing RAB. The ETT adapter was connected to the 6.5 cuffed ETT, and RAB was performed without interruption. We are not aware of any other reported cases in the literature describing the use of robotic bronchoscopy through a small nasal airway. This case highlights a deviation from recommended protocols suggesting larger oral ETT in patients undergoing RAB. This illustrated approach of using a smaller ETT, via oral or nasal routes, could be useful in patients with history of head and neck cancers, limited jaw movement, and in patients with a known history of tracheal stenosis.

Case 2 highlights the reach of RAB beyond the airway walls when the catheter is parked in close proximity to the target. We have experienced this type of reach in intraparenchymal lesions without a bronchus sign, and sometimes without a R-EBUS signal, by extending a needle through an airway wall into a lesion in close proximity to the tip of the Ion catheter. Multiple reports have documented the advantage of RAB in nodules with no bronchus sign, with similar diagnostic yield when compared to lesions with bronchus sign.3,12 In this case, we chose lymph node station 5 as a target during the planning phase considering its proximity to a branch of the LUL bronchus. Since rapid on-site cytology was negative from the LUL nodule, we drove the IRB catheter and parked it 7 mm away from lymph node station 5. We then extended a 21-gauge needle under fluoroscopic guidance and obtained a sample, which came back consistent with small cell carcinoma. The final pathology from LUL nodule was non-diagnostic. This approach has definitely allowed us to avoid further invasive procedures such as Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) biopsy and mediastinoscopy.

Case 3 shows the utility of RAB in recurrent lung cancer at a previous stump site. The new lesion was certainly challenging to access with conventional bronchoscopy (lesion behind the stump) or CT-guided biopsy considering its central location. In addition, the patient was not a good surgical candidate. When we considered attempting to biopsy this lesion with RAB, we were concerned about applying excessive pressure with the catheter against the airway stump. The drive force signal feature was helpful in alleviating these concerns. In addition, we used a diagnostic bronchoscope which was navigated through the airways on the side of the ETT. We wanted to document the position of the Ion catheter tip in close proximity to the stump while avoiding excessive pressure. A 25-gauge needle was used through the airway wall, and the lesion was sampled with positive rapid on-site cytology examination.

Conclusion

This case series highlights unusual applications of RAB in clinically challenging situations. The advanced features of RAB in these scenarios allowed for obtaining diagnostic samples in patients who otherwise would have required surgical and more invasive approaches. RAB was used unconventionally in this series to access through a nasal artificial airway, to sample mediastinal lymph node stations not reachable with convex EBUS bronchoscope, and to reach recurrent lung cancer hidden behind a previous airway stump. RAB systems provide advantageous catheter maneuverability and stability, and these promising features should be explored further in clinical situations not amenable to conventional bronchoscopy.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tar-10.1177_17534666241259369 for Unlocking the potential of robotic-assisted bronchoscopy: overcoming challenging anatomy and locations by Wissam Abouzgheib, Christopher Ambrogi and Michele Chai in Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Wissam Abouzgheib  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5202-4096

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5202-4096

Christopher Ambrogi  https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1505-1866

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1505-1866

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Wissam Abouzgheib, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, 3 Cooper plaza, suite 312, Camden, NJ 08103, USA.

Christopher Ambrogi, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ, USA.

Michele Chai, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ, USA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Followed Cooper University Hospital’s IRB guidelines stating that case series consisting of 5 or fewer cases do not need to be submitted or reviewed by the IRB.

Consent for publication: Consent was obtained verbally over the phone and witnessed by Dr. Abouzgheib and Michele Chai. Written consent was not obtained due to patients not being able to travel into office to sign.

Author contributions: Wissam Abouzgheib: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Christopher Ambrogi: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Michele Chai: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: Available upon request

References

- 1. Agrawal A, Hogarth DK, Murgu S. Robotic bronchoscopy for pulmonary lesions: a review of existing technologies and clinical data. J Thorac Dis 2020; 12: 3279–3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diddams MJ, Lee HJ. Robotic bronchoscopy: review of three systems. Life (Basel). 2023; 13: 354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kalchiem-Dekel O, Connolly JG, Lin IH, et al. Shape-sensing robotic-assisted bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of pulmonary parenchymal lesions. Chest 2022; 161: 572–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ali MS, Ghori UK, Wayne MT, et al. Diagnostic performance and safety profile of robotic-assisted bronchoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023; 20: 1801–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ho E, Hedstrom G, Murgu S. Robotic bronchoscopy in diagnosing lung cancer-the evidence, tips and tricks: a clinical practice review. Ann Transl Med 2023; 11: 359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar A, Caceres JD, Vaithilingam S, et al. Robotic bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesion biopsy: evidence-based review of the two platforms. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021; 11: 354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu M, Nath S, Semaan RW. A review of robotic-assisted bronchoscopy platforms in the sampling of peripheral pulmonary lesions. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ravikumar N, Ho E, Wagh A, et al. Advanced imaging for robotic bronchoscopy: a review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023; 13: 990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agrawal A, Ho E, Chaddha U, et al. Factors associated with diagnostic accuracy of robotic bronchoscopy with 12-month follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg 2023; 115: 1361–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khouzam MS, Wood DE, Vigneswaran W, et al. Impact of federal lung cancer screening policy on the incidence of early-stage lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2023; 115: 827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ortiz-Jaimes G, Reisenauer J. Real-world impact of robotic-assisted bronchoscopy on the staging and diagnosis of lung cancer: the shape of current and potential opportunities. Pragmat Obs Res 2023; 14: 75–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen AC, Pastis NJ, Jr., Mahajan AK, et al. Robotic bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: a multicenter pilot and feasibility Study (BENEFIT). Chest 2021; 159: 845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al.; the CARE Group. The CARE Guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Glob Adv Health Med 2013; 2: 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tar-10.1177_17534666241259369 for Unlocking the potential of robotic-assisted bronchoscopy: overcoming challenging anatomy and locations by Wissam Abouzgheib, Christopher Ambrogi and Michele Chai in Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease