Abstract

Objectives:

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a leader in generating transformational research across the cancer care continuum. Given the extensive body of cancer-related literature utilizing VHA data, our objectives are to: (1) describe the VHA data sources available for conducting cancer-related research, and (2) discuss examples of published cancer research using each data source.

Methods:

We identified commonly used data sources within the VHA and reviewed previously published cancer-related research that utilized these data sources. In addition, we reviewed VHA clinical and health services research web pages and consulted with a multidisciplinary group of cancer researchers that included hematologist/oncologists, health services researchers, and epidemiologists.

Results:

Commonly used VHA cancer data sources include the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System, the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW)-Oncology Raw Domain (subset of data within the CDW), and the VA Cancer Care Cube (Cube). While no reference standard exists for cancer case ascertainment, the VACCR provides a systematic approach to ensure the complete capture of clinical history, cancer diagnosis, and treatment. Like many population-based cancer registries, a significant time lag exists due to constrained resources, which may make it best suited for historical epidemiologic studies. The CDW-Oncology Raw Domain and the Cube contain national information on incident cancers which may be useful for case ascertainment and prospective recruitment; however, additional resources may be needed for data cleaning.

Conclusions:

The VHA has a wealth of data sources available for cancer-related research. It is imperative that researchers recognize the advantages and disadvantages of each data source to ensure their research questions are addressed appropriately.

Keywords: data sources, neoplasms, oncology, population health, research methods, Veterans Health Administration

Introduction

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated provider of cancer care in the United States, diagnosing and/or treating approximately 50,000 patients at 129 medical centers annually.1,2 In addition to being a leading health care provider, the VHA has also generated transformational research across the cancer care continuum. Pivotal cancer research includes, but is not limited to, linking cigarette smoking to precancerous lesions,3 demonstrating the superiority of colonoscopy over sigmoidoscopy for colorectal cancer screening,3 determining that observation is as effective as surgery for the treatment of early-stage prostate cancer,4 establishing dental treatment guidelines for patients with head and neck cancers,5,6 and implementing a population-based lung cancer screening program.7-11 The quality of VHA cancer care has also been thoroughly evaluated12-15 and the care delivered in the VHA compares favorably with other health insurers and health care systems. For instance, when compared with Medicare, cancer-related imaging is used more efficiently at the VHA16 and survival rates are higher among older patients with colorectal and non-small lung cancer treated at the VHA.17 The extensive body of published cancer research is largely possible due to the availability of vast cancer data sources within the VHA. Our objective is to describe existing VHA data sources available for conducting cancer-focused health services research.

VHA Cancer Data Sources

The VHA has several cancer-related data sources, some originating from clinically collected data that are updated daily in the national electronic health record (EHR) system, and others assembled for a specific, often time-limited purpose (eg, a single research study). We describe the primary data sources available within the VHA for conducting cancer-related research (Table 1), the relative advantages of each data source (Table 2), and examples of published work and current research using each data source (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 1.

Description of VHA Cancer Data Sources

| VHA Data Source | Primary Purpose | Brief Description | Cancers | Domains | Selected References | Data Steward | Special Considerations * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA Central Cancer Registry |

|

Record of reportable cancers diagnosed or treated in the VHA; data is abstracted and validated by site-based tumor registrars | All cancers |

|

|

The timeline for DUA approval may be significant and, once a DUA is in place, receiving data hinges on availability of staff. This may mean that approved DUAs are not processed. | |

| CDW-Oncology Raw Domain |

|

Information pertaining to cancer diagnosis and care delivery originating from the electronic health record | All cancers |

|

|

The data have not been cleaned. It is relatively straightforward to link with other CDW data including information about VHA health service use and survival. |

|

| VA Cancer Care Cube |

|

The Oncology Domain files from the CDW are accessible via the Cube | All cancers |

|

|

The Cube is accessible using the Pyramid platform. | |

| Facility** Oncology Survey |

|

Cross-sectional survey of resources available at VHA facilities providing cancer care | N/A | VHA facility:

|

|

Site-specific data not available for 2005 survey responses. |

Abbreviations: CDW, Corporate Data Warehouse; DUA, data use agreement; HAIG, Healthcare Analysis & Information Group; NDS, National Data Systems; PCS, Patient Care Services; VA, Veterans Affairs; VHA; Veterans Health Administration; VSSC, Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center Capital Assets

Special considerations are all opinions of the authors based on their personal experiences.

The Facility Oncology Survey was administered in 2005, 2009, and 2016.

Table 2.

Relative Advantages of VHA Cancer Data Sources

| VHA Data Source * | Advantage | Disadvantage | Suggested Possible Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| VA Central Cancer Registry |

|

|

|

| CDW-Oncology Raw Domain |

|

|

|

| VA Cancer Care Cube |

|

|

|

CDW, Corporate Data Warehouse; EHR, electronic health record; VA, Veterans Affairs; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Data sources described are those where data is available at the case level.

Table 3.

Recent Health Services Research and Development Studies using VHA Cancer Data Sources

| Grant Number and Title | Cancer Type | VHA Data Source | Data Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDA 13-025 Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Care in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System | Colorectal cancer |

|

|

| CDA 16-151 Implementing Shared Decision-Making for Cancer Screening in Primary Care | Lung cancer | Corporate Data Warehouse (health factor data and patient tables) |

|

| IIR 12-378 Impact of Family History and Decision Support on High-Risk Cancer Screening | Colorectal cancer | Corporate Data Warehouse |

|

| IIR 16-232 Directed Evaluation of Provider Learning Modules to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism after Major Cancer Surgery | Multiple |

|

|

CDA, Career Development Award; CPT, current procedural terminology; IIR, investigator-initiated research; VA, Veterans Affairs; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

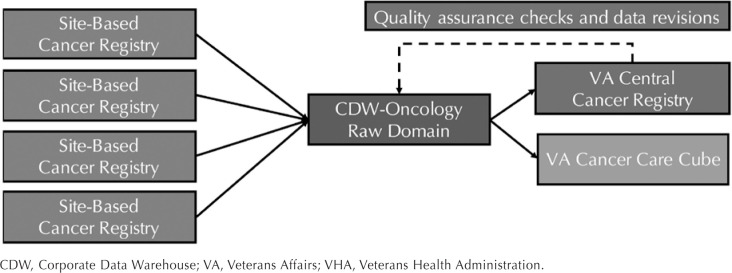

It is worth noting that the data sources reviewed are those that that are most commonly used or are routinely accessed for clinical operations, health services research, and preliminary, feasibility, retrospective, and observational research studies. Herein, we describe the following 4 related VHA cancer data sources: (1) the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System, (2) the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), (3) the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW)-Oncology Raw Domain, and (4) the VA Cancer Care Cube (Cube) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data Flow Between VHA Cancer Data Sources

CDW, Corporate Data Warehouse; VA, Veterans Affairs; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

VA Cancer Registry System

In 1998, a VA policy directive established the VA Cancer Registry System which consists of site-based cancer registries that populate the central component of the system, the aggregated VACCR. The VA Cancer Registry System adheres to the standards developed by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR).18 The system includes data elements required by the Commission on Cancer's Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards (FORDS) manual (eg, patient demographics, cancer or tumor characteristics, stage of disease)19 or the Standards for Oncology Registry Entry manual (STORE, which replaced FORDS 2018).20 Both manuals ensure that registry data are structured and maintained with standardized quality controls and thus support the meaningful evaluation of cancer diagnoses and treatment. The VA Cancer Registry System also includes cases captured by medical centers whose geographic regions are covered by the National Cancer Institute (NCI)'s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.21 Lastly, the VA Cancer Registry System incorporates additional VHA-defined data elements (eg, era and branch of military service, exposure to asbestos, Agent Orange, and ionizing radiation).

It is worth noting that the VHA is distinct from other military health care providers (eg, Department of Defense) and does not routinely share cancer registry data with external providers. In an effort to provide a complete understanding of the national burden of cancer, VHA Directive 1072 enables VHA medical centers to report cancer data to state registries that completed a data-sharing agreement and have satisfied VHA data security standards.22 The Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital (Chicago, Illinois), Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (Houston, Texas), George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center (Salt Lake City, Utah), and Kansas City VA Medical Center (Kansas City, Missouri) are examples of VHA facilities that successfully report cancer data with their affiliated state cancer registry.

Site-Based Cancer Registries: Since 2001, all VHA medical centers diagnosing or treating patients with cancer have implemented an operational cancer registry.2 Each site-based registry is maintained by at least 1 registrar (typically a National Cancer Registrars Association [NCRA]-certified tumor registrar), who uses a custom VHA software program called OncoTraX to perform casefinding and follow-up; case abstraction and updating; and data transmission and reporting. Generally, site-based registrars are instructed to abstract cases diagnosed or treated within the VHA, which may necessitate identifying and recording information regarding diagnostic and therapeutic care received outside of the VHA (eg, review of available outside medical records using VistA Imaging Display, a system that integrates clinical images and scanned documents into the EHR).23 It should be noted that site-based cancer registries do not capture information regarding cancer screening. Consistent with other population-based registries, a registry record is only created for patients that receive a cancer diagnosis including in situ cancers; no registry entry will be created for patients who have undergone screening but do not have a confirmed diagnosis of neoplasia. Exceptions include data on squamous and basal cell carcinomas with positive lymph nodes or distant metastasis at diagnosis, intraepithelial neoplasia grade III (eg, high-grade dysplasia bordering on in situ), and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Cases of nonmalignant primary intracranial and central nervous system tumors are required to be abstracted and reported nationally.24

Site-based cancer registry data have been used to estimate the incidence of multiple primary malignancies25 and compare patterns of diagnosis, treatment, and survival in non-small cell lung cancer to those reported in the SEER registry.26 However, the availability and process for acquiring site-based registry data varies and is managed at the medical center-level.

VA Central Cancer Registry: Formally recognized in 2003,2 VACCR consists of aggregate case abstracts from site-based cancer registries across the VHA. Once cases are abstracted and have completed the site-based quality assurance process, data are transmitted via OncoTraX to the VACCR production database. Using the Rocky Mountain Cancer Data Systems, a Windows-based software program designed to facilitate data entry and statistical analysis, VACCR staff perform additional quality assurance checks (eg, correct duplicated data).27

Data aggregation and error-checking processes are a key strength of the VACCR that ensure data are complete, up to date, and meet national standards for cancer reporting. Previous research has suggested that the data available in the VACCR have higher specificity, sensitivity, and positive predictive value (≥90%) compared to cancer case identification using administrative diagnosis codes.28 Prior studies have demonstrated that patient demographics and cancer-specific data (eg, stage, site, treatment) in the VACCR are ≥90% in both completion and concordance with the EHR.12,29,30 However, to our knowledge, the contents of VACCR have not been validated through a secondary abstraction or retrospective data comparison. At the time of this manuscript, it is unclear if this data source will continue to undergo quality assurance and oversight processes due to staffing availability. Therefore, researchers should conduct chart reviews and error-checking to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the data.

Similar to other population-based cancer registries, the VACCR relies on manual abstraction of cancer-specific data from EHRs and supporting documentation, often resulting in significant delays in data entry and aggregation. Delays, which vary across medical centers, are not easily identifiable, and occur for a number of reasons (eg, limited resources or staff). Such delays have contributed to a VACCR reporting delay of 48–72 months. Reporting delays are common in cancer registries; the population-based SEER Program registry has reporting delays of approximately 22 months and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) has a reporting interval of 23 months.31,32 It is important to note that there are 2 types of reporting delays: (1) the time between receipt of a cancer diagnosis and the case being reported to a registry; and (2) the time until which reported data becomes available to users. Due to these delays, we recommend using the VACCR in instances when capturing recently diagnosed cases is not necessary.

Traditionally, the VACCR has been the most commonly used data source for VHA cancer-related research. The aggregated registry data have been used to evaluate health services and epidemiology research questions related to estimating cancer incidence, survival,33,34 and describing characteristics of cancer cases,1,35-37 as well as for case-control studies,38 and ascertainment of cancer cases for both retro-spective studies39-43 and research involving primary data collection.44

Corporate Data Warehouse-Oncology Raw Domain

The CDW45,46 is a national VHA database comprised of financial, administration, and clinical information which is organized into domains and stored in a Structured Query Language (SQL) relational database structure.47 The CDW-Oncology Raw Domain is one of many raw domains and consists of a set of relational database tables, of which the following 3 tables are most commonly used for cohort creation: 1 containing general patient information (eg, identifiers); 1 containing diagnosing and/or treating medical center information; and the last containing cancer-specific information (eg, diagnosis, tumor, and treatment characteristics).45

The CDW-Oncology Raw Domain and the VACCR originate with information from site-based cancer registries, therefore it is worth comparing these 2 data sources. While a reporting delay still occurs due to limited resources, the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain is updated on a biweekly basis (consistent with most CDW data) and thus is timelier than the VACCR. In addition, being part of the data warehouse allows for relatively easy linkage between CDW-Oncology Raw Domain tables and other CDW data tables (eg, laboratory results, procedures, comorbid diagnoses, vital status, prescription benefits). The most notable limitation is that CDW-Oncology Raw Domain data are “raw,” for there are no centralized error identification or quality assurance processes. Therefore, researchers will need to ensure data validity. One common data cleaning practice is to check for duplicate records and account for individuals with various identifiers across CDW tables. Despite this limitation, the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain has demonstrated similar sensitivity and specificity (≥90%) for colorectal cancer case ascertainment when compared to the VACCR and administrative diagnostic codes.48

CDW data and the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain have been widely used in research. Specifically, these data have been used for patient identification,49,50 case-control studies,50 and to address health services research questions related to the identification of delays in cancer diagnosis.51

VA Cancer Care Cube

The Cube was designed for oncology stakeholders, including VHA clinicians and operations groups that need access to cancer-related data in near real-time. The Cube, which was built and is maintained by the VHA Support Service Center Capital Assets (VSSC) on the Pyramid platform, is comprised of information contained in the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain tables. Information about incident cancer cases (site-based, regional, national) is pulled into the Cube when identified criteria (eg, diagnosis date, primary cancer site, course of therapy) are applied to the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain tables. Since the Cube consists of raw data, researchers are able to monitor the timeliness and completeness of the data. For example, the Cube includes information on patients with incomplete and complete registry abstraction data, which in turn, allows potential cases to be identified earlier and diagnostic or clinical information to be tracked as it becomes available over time.

Accessing the Cube is different than both the VACCR and CDW-Oncology Raw Domain. First, accessing the VACCR and CDW-Oncology Raw Domain require a fully executed data use agreement (DUA) with Patient Care Services and the Corporate Data Warehouse, respectively. Prior to using the Cube, researchers must submit Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval or a DUA request to Patient Care Services. However, other nonresearch uses, including clinical care, may not be subject to approval processes. Researchers outside of the VHA may access the Cube by identifying a VHA-affiliated collaborator and pursuing regulatory approval (eg, IRB approval or exemption). Second, while the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain typically requires a user within the VHA computing network to access the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) and query the data via a Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio, the Cube is a business intelligence application (point-and-click interface) that allows a user to access data over the VA intranet.

A primary advantage of the Cube is a user's ability to create reports and cross-tabulations within the tool via a graphical interface without the need to write SQL queries. Despite increased usability, the ability to validate the resulting reports is difficult to achieve. While data precision is improving, it is important to note that the Cube may overestimate cases and should be used as an upper bound to understand volume (especially when planning a study). Therefore, researchers may need to conduct chart reviews to confirm the accuracy of cancer diagnoses prior to conducting prospective or retrospective studies.

The Cube has commonly been used for cancer case ascertainment. For example, researchers have used the Cube to prospectively identify patients for qualitative interviews.52 In addition, the Cube has been used to assess the association between staging and survival in patients with colorectal cancer53 and to evaluate the relationship between the Commission on Cancer accreditation and treatment and survival in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer.54

Other VHA Cancer Data Sources

There are several additional oncology data resources, which are often used for a specific purpose (eg, a single research study) or to address a specific cancer population, that may be of interest to clinicians and researchers. Below, we highlight 3 data sources: (1) the External Peer Review Program (EPRP), (2) the Facility Oncology Survey, and (3) the Epidemiology of Cancer among Veterans (EpiCAN).

The EPRP is an example of unique data source that is used by VHA officials for monitoring facility performance and determining areas for quality improvement.55 The EPRP data are narrow in scope (eg, focused on a single cancer during a narrow diagnosis time frame) and contain information that is manually extracted from the EHR and chart abstraction. However, researchers using EPRP data may have to conduct additional chart reviews to appropriately define measures. For example, the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 (ACE-27), a comorbidity measure contained in the lung cancer EPRP data,56 requires chart reviews to appropriately grade conditions as mild, moderate, or severe.57 EPRP cancer data have been used in studies focused on evaluating racial disparities in care and survival in patients with colorectal cancer,14,15,58 assessing the use of expectant management among patients with prostate cancer,59 and examining refusal of or contraindications with recommended therapy and racial differences in receipt of surgery in patients with non-small cell lung cancer.56,60

The Facility Oncology Survey is a cross-sectional survey of all VHA facilities that provide cancer care. The survey was administered by the Healthcare Analysis and Information Group (HAIG) 3 times (2005, 2009, 2016), and captures resource availability—services, staffing, equipment, space—for cancer care delivery. For example, the survey has identified which medical centers have tumor boards and various certifications (eg, American College of Surgeons), as well as documented available imaging technologies and consultation services (eg, inpatient and outpatient palliative care consultations).61 To access the Facility Oncology Survey data, researchers must first receive DUA approval from Patient Care Services and then send a copy of the DUA to the HAIG. The Facility Oncology Survey has been used for research purposes,59,61 but it has not been as widely used as the previously described data sources. Researchers focused on describing cancer treatment variation across the VHA should consider using the Facility Oncology Survey to account for medical center characteristics.

In contrast to the other VHA cancer-related data sources previously described, EpiCAN is a research study that incorporates the aforementioned data sources.62 Specifically, EpiCAN identifies cancer cases using the VACCR and the CDW-Oncology Raw Domain, and provides a comprehensive assessment of VHA cancer care by linking information from the CDW, National Death Index, and the Facility Oncology Survey. Due to these data linkages, the objectives of the EpiCAN study are twofold: (1) to broadly evaluate cancer incidence, treatment, survivorship, and outcomes in the VHA; and (2) to identify improvements in and ensure the delivery of high-quality cancer care. A primary goal of EpiCAN is to create a unified data source for others within the VHA community to use to answer research questions. Other cancer-specific research and operations studies have followed suit and linked VA data sources with supplemental cancer registry sources to develop a unified cancer resource.63

Conclusion

The VHA is a nationwide high-volume provider of cancer care and has a wealth of data sources that are well-suited for answering health services, clinical, epidemiologic, and population health research questions. We described several commonly used VHA cancer-related data sources available for prospective and retrospective studies; however, this is not an exhaustive list. Existing data sources are routinely updated, new sources are being created, and non-cancer-specific data sources may also be relevant. For example, additional information available within the CDW (eg, diagnostic codes) have been used successfully to identify cohorts in VHA cancer-related research,64,65 and thus may be an appropriate approach for addressing many cancer-related research questions. Prior to commencing a study, researchers should understand the advantages and disadvantages of the available VHA cancer data sources to ensure appropriate alignment with their research question and scope.

Footnotes

Dr. Zullig reports research grant support from the PhRMA Foundation and Proteus Digital Health, as well as consulting from Novartis. Dr. Slatore receives grant funding from the Knight Cancer Institute to develop a lung cancer risk prediction model that utilizes machine learning software from a for-profit company, Optellum.

The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, or in the preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Dr. Zullig was supported by a VA Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Career Development Award (CDA 13-025). Dr. Slatore was supported by resources from the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, OR.

This work was supported by the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT), (CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System.

Originally published in Fall 2019;46(3):76-83.

References

- 1.Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883–e1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G.. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer: Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilt TJ. The Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial: VA/NCI/AHRQ Cooperative Studies Program #407 (PIVOT): design and baseline results of a randomized controlled trial comparing radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting for men with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(45):184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson PA, Kansara S, Chen GG, et al. Treatment patterns in veterans with laryngeal and oropharyngeal cancer and impact on survival. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3(4):275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White JM, Panchal NH, Wehler CJ, et al. Department of Veterans Affairs consensus: preradiation dental treatment guidelines for patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41(5):1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caverly TJ, Fagerlin A, Wiener RS, et al. Comparison of observed harms and expected mortality benefit for persons in the Veterans Health Affairs Lung Cancer Screening Demonstration Project. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):426–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartman E, Jankowich M, Baptiste J, Schiff A, Nici L.. Outcomes of the first three years of a lung cancer screening program at a Veterans Affairs medical center. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(11):1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okereke IC, Bates MF, Jankowich MD, et al. Effects of implementation of lung cancer screening at one Veterans Affairs medical center. Chest. 2016;150(5):1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeliadt SB, Heffner JL, Sayre G, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about smoking cessation in the context of lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1530–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, et al. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3176–3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson GL, Zullig LL, Zafar SY, et al. Using NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology to measure the quality of colorectal cancer care in the veterans health administration. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(4):431–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale D, Weinberger M, Reeve BB, Jackson GL.. Examining potential colorectal cancer care disparities in the Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3579–3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Weinberger M, Provenzale D, Reeve BB, Carpenter WR.. An examination of racial differences in process and outcome of colorectal cancer care quality among users of the veterans affairs health care system. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12(4):255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McWilliams JM, Dalton JB, Landrum MB, Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Keating NL.. Geographic variation in cancer-related imaging: Veterans Affairs health care system versus Medicare. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landrum MB, Keating NL, Lamont EB, et al. Survival of older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus fee-for-service Medicare. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1072–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.North American Association of Central Registries website. https://www.naaccr.org/. Accessed November 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Registry manuals. American College of Surgeons website. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/call-for-data/cocmanuals. Accessed April 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Registry manuals: Standards for Oncology Registry Entry (STORE) 2018. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/call-for-data/cocmanuals. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- 21.List of SEER registries. National Cancer Institute website. https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Release of VA Data to State Cancer Registries. VHA Directive 1072. July 23, 2014. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3028. Accessed November 7, 2019.

- 23.VistA Imaging Overview. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. https://www.va.gov/health/imaging/overview.asp. Updated May 11, 2015. Accessed November 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Commission on Cancer. Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards. Chicago; IL: American College of Surgeons; 2016. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/fords-2016.ashx?la=en. Accessed August 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell S, Tarchand G, Rector T, Klein M.. Synchronous and metachronous malignancies: analysis of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs (VA) tumor registry. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(8):1565–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeliadt SB, Sekaran NK, Hu EY, et al. Comparison of demographic characteristics, surgical resection patterns, and survival outcomes for veterans and nonveterans with non-small cell lung cancer in the Pacific Northwest. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(10):1726–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocky Mountain Cancer Data Systems (RMCDS). US Department of Veterans Affairs website. https://www.oit.va.gov/Services/TRM/ToolPage.aspx?tid=7358. Updated November 13, 2018. Accessed August 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park LS, Tate JP, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Cancer incidence in HIV-infected versus uninfected veterans: comparison of cancer registry and ICD-9 code diagnoses. J AIDS Clin Res. 2014;5(7):1000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamont EB, Landrum MB, Keating NL, Boseman SR, McNeil BJ.. Evaluating colorectal cancer care in the Veterans Health Administration: how good are the data? J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2(3):187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherer EA, Fisher DA, Barnd J, Jackson GL, Provenzale D, Haggstrom DA.. The accuracy and completeness for receipt of colorectal cancer care using Veterans Health Administration administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cancer incidence rates adjusted for reporting delay. National Cancer Institute website. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/delay/. Accessed April 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Interpreting the Incidence Data: change to the 2000 U.S. standard population. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/technical_notes/interpreting/incidence.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/technical_notes/interpreting/incidence.htm. Updated May 29, 2019. Accessed November 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyer MJ, Williams CD, Harpole DH, Onaitis MW, Kelley MJ, Salama JK.. Improved survival of stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a VA central cancer registry analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(12):1814–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganti AK, Gonsalves W, Loberiza FR Jr, et al. Effect of surgical intervention on survival of patients with clinical N2 non-small cell lung cancer: a Veterans' Affairs central cancer registry (VACCR) database analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(2):142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colonna S, Halwani A, Ying J, Buys S, Sweeney C.. Women with breast cancer in the Veterans Health Administration: demographics, breast cancer characteristics, and trends. Med Care. 2015;53(4 suppl 1):S149–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zullig LL, Goldstein KM, Sims KJ, et al. Cancer among women treated in the Veterans Affairs healthcare system. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(2):268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zullig LL, Smith VA, Jackson GL, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics from the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15(4):e199–e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zullig LL SV, Lindquist JH, Williams CD, et al. Cardiovascular disease-related chronic conditions among Veterans Affairs nonmetastatic colorectal cancer survivors: a matched case–control analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:6793–6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulus JK, Williams CD, Cossor FI, Kelley MJ, Martell RE.. Metformin, diabetes, and survival among U.S. veterans with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(10):1418–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sehdev A, Sherer EA, Hui SL, Wu J, Haggstrom DA.. Patterns of computed tomography surveillance in survivors of colorectal cancer at Veterans Health Administration facilities. Cancer. 2017;123(12):2338–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629–3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tukey MH, Faricy-Anderson K, Corneau E, Youssef R, Mor V.. Procedural aggressiveness in veterans with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams CD, Gajra A, Ganti AK, Kelley MJ.. Use and impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(13):1939–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Ryn M, Phelan SM, Arora NK, et al. Patient-reported quality of supportive care among patients with colorectal cancer in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):809–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price LE, Shea K, Gephart S.. The Veterans Affairs's Corporate Data Warehouse: uses and implications for nursing research and practice. Nurs Adm Q. 2015;39(4):311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). US Department of Veterans Affairs website. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm. Accessed March 28, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonsoulin M. CDW: A Conceptual Overview 2017. Presented March 29, 2017. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/2287-notes.pdf.

- 48.Earles A, Liu L, Bustamante R, et al. Structured approach for evaluating strategies for cancer ascertainment using large-scale electronic health record data. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018;2:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mowery A, Conlin M, Clayburgh D.. Risk of head and neck cancer in patients with prior hematologic malignant tumors [published online May 2, 2019]. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papaleontiou M, Banerjee M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Hawley ST, Haymart MR.. Risk of osteoporosis and fractures in patients with thyroid cancer: a case-control study in U.S. veterans. Oncologist. 2019;24(9):1166–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy DR, Meyer AND, Vaghani V, et al. Development and validation of trigger algorithms to identify delays in diagnostic evaluation of gastroenterological cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(1):90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zullig LL, Goldstein KM, Bosworth HB, et al. Chronic disease management perspectives of colorectal cancer survivors using the Veterans Affairs healthcare system: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Virk GS, Jafri M, Mehdi S, Ashley C.. Staging and survival of colorectal cancer (CRC) in octogenarians: Nationwide Study of US Veterans. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(1):12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azar I, Virk G, Esfandiarifard S, Wazir A, Mehdi S.. Treatment and survival rates of stage IV pancreatic cancer at VA hospitals: a nation-wide study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(4):703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hysong SJ, Teal CR, Khan MJ, Haidet P.. Improving quality of care through improved audit and feedback. Implement Sci. 2012;7:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams CD, Stechuchak KM, Zullig LL, Provenzale D, Kelley MJ.. Influence of comorbidity on racial differences in receipt of surgery among US veterans with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel EL, Jr.. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2441–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale DT, et al. The association of race with timeliness of care and survival among Veterans Affairs health care system patients with late-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2013;5:157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Filson CP, Shelton JB, Tan HJ, et al. Expectant management of veterans with early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(4):626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryoo JJ, Ordin DL, Antonio AL, et al. Patient preference and contraindications in measuring quality of care: what do administrative data miss? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2716–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryoo JJ, Malin JL, Ordin DL, et al. Facility characteristics and quality of lung cancer care in an integrated health care system. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(4):447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams CD, Gu L, Redding T, et al. Poster abstract: Trends in cancer incidence and survival in the Veterans Health Administration. https://www.fedprac-digital.com/federalpractitioner/2018_avaho_abstracts/MobilePagedReplica.action?pm=1&folio=S32#pg34. Accessed April 28, 2019.

- 63.Office of Research & Development: Cancer Outcomes Research Program. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. https://www.research.va.gov/programs/csp/cspec/cancer_outcomes.cfm. Accessed April 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karnes RJ, Mackintosh FR, Morrell CH, et al. Prostate-specific antigen trends predict the probability of prostate cancer in a very large US Veterans Affairs cohort. Front Oncol. 2018;8:296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schroeck FR, Sirovich B, Seigne JD, Robertson DJ, Goodney PP.. Assembling and validating data from multiple sources to study care for Veterans with bladder cancer. BMC Urol. 2017;17(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoffman RM, Shi Y, Freedland SJ, Keating NL, Walter LC.. Treatment patterns for older veterans with localized prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(5):769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shelton JB, Skolarus TA, Ordin D, et al. Validating electronic cancer quality measures at Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(12):1041–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mescher C, Gilbertson D, Randall NM, et al. The impact of Agent Orange exposure on prognosis and management in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a National Veteran Affairs Tumor Registry Study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(6):1348–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]