Abstract

Background: In the last decade, increasing evidence has suggested that high-grade serous ovarian cancers may have their origin in the fallopian tube rather than the ovary. This emerging theory presents an opportunity to prevent epithelial ovarian cancer by incorporating prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy into all surgical procedures for average-risk women. The aim of this review is to investigate the hypothesis that bilateral salpingectomy (BS) may have a negative impact on ovarian reserve, not only following hysterectomy for benign uterine pathologies but also when performed during cesarean sections as a method of sterilization or as a treatment for hydrosalpinx in Assisted Reproductive Technology interventions. Methods: PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Cochrane were searched for original studies, meta-analyses, and opinion articles published between 2014 and 2024. Results: Out of 114 records from the database search, after the removal of duplicates, 102 articles were considered relevant for the current study. Conclusions: Performing opportunistic salpingectomy seems to have no adverse impact on ovarian function in the short term. However, because there is an existing risk of damaging ovarian blood supply during salpingectomy, there are concerns about potential long-term adverse effects on the ovarian reserve, which need further investigation.

Keywords: opportunistic salpingectomy, hysterectomy, ovarian reserve, ovarian cancer

1. Introduction

Among women, ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women and exhibits the highest mortality rate of all gynecologic malignancies. The overall survival rate for epithelial ovarian cancer has improved significantly in the past 50 years [1]. Current efforts to screen for ovarian cancer have proven ineffective, with associated false-positive results, leading to unnecessary surgery and complications associated with surgeries [2].

A hypothesis has been formulated, proposing that the origin of the most frequent type of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC), is the epithelium of the fallopian tube. For this EOC subtype, no precursive lesions have been found in the ovaries; however, a potential precursor for HGSC, known as serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC), has been observed in the fimbrial part of the fallopian tube [3]. These STIC lesions are thought to implant on the ovarian or peritoneal surfaces and, over a concealed period, progress into rapidly growing HGSC. Therefore, bilateral salpingectomy at the time of a planned intra-abdominal surgery, an intervention called “opportunistic salpingectomy”, could become the primary prevention method for EOC [4,5].

In the last decade, opportunistic salpingectomy has become the standard of care for EOC risk reduction in women undergoing interventions for benign gynecological pathologies [6]. Furthermore, there is a growing consideration for advocating for salpingectomy over proximal tubal occlusion during sterilization procedures for women who have finished childbearing [7,8]. There are several studies that support the endorsement of bilateral salpingectomy as a contraceptive method in women who desire permanent sterilization at the time of cesarean delivery [9,10].

Another matter of debate is the surgical technique that should be implemented for the treatment of hydrosalpinx before IVF (in vitro fertilization). Proximal tubal occlusion might be a viable alternative to salpingectomy, with the advantages of fewer surgical risks and avoiding the disruption of normal blood flow to the ovary [11].

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a PubMed/Medline/Google Scholar/Cochrane database search in March 2024. We targeted articles published from 2014 to 2024, regarding the effect of bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian reserve during interventions for benign gynecological pathologies. We used controlled vocabulary, more exactly, MeSH terms: “opportunistic” + “salpingectomy” + “ovarian” + “function”, and also entry terms, like: “ovarian” + “reserve” + “bilateral” + “salpingectomy”, “hysterectomy” + “bilateral” + “salpingectomy”. For articles that analyzed the results of bilateral salpingectomy during cesarean sections, we used the following terms: “salpingectomy” + “cesarean section” + “ovarian” + “reserve”; for the articles regarding the effects of salpingectomy on IVF cycle results, we used the following terms: “ART” (Assisted Reproductive Technology) + “after” + “salpingectomy” and “IVF” + “salpingectomy”.

We considered relevant articles that met the following conditions: (1) retrospective or prospective studies, as well as meta-analyses, which assessed reproductive-age women between 30 and 50 years old, who requested a sterilization method, (proximal tubal occlusion orbilateral salpingectomy following cesarean section) or articles that included the same cathegory of patients to whom a tubal intervention for hydrosalpinx was made (2) articles that included perimenopausal patients with bilateral salpingectomy as a method of ovarian cancer prophylaxis during abdominal or laparoscopic hysterectomy; (3) those that evaluated pre/post-operative serum levels of AMH (Anti-Müllerian Hormone), FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone), AFC (Antral Follicle Count), and estradiol, characteristics of the IVF procedure, and their impact on ovarian response during controlled stimulation cycles. Articles in languages other than English and papers without an available full text were excluded. Other exclusion criteria involved articles that did not include preoperativeand postoperativeevaluation and studies that used animals or in vitro models.

The primary objective was to assess whether opportunistic salpingectomy during hysterectomy for benign pathologies of the uterus might have a negative effect on ovarian function and if the type of surgical intervention addressed (laparotomy/laparoscopy) influences post-operative ovarian reserve. Serum Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH), and Antral Follicle Count (AFC) were considered markers for evaluating ovarian reserve. We observed and compared the variations between these markers pre-operatively and post-operatively. The secondary objective was to assess the risks and benefits of salpingectomy at the time of cesarean section as a means to reduce ovarian cancer for women who have chosen to conclude childbearing.

The third objective was to evaluate the potential negative effect of tubal surgery on ovarian response in controlled stimulation cycles.

Given the objectives of this systematic review, the control groups were chosen as follows: The first control group consisted of women who underwent hysterectomy without opportunistic salpingectomy. The second control group included women who had proximal tubal ligation instead of bilateral salpingectomy. The third control group comprised patients who used assisted reproductive techniques and did not have their fallopian tubes removed.

3. Results

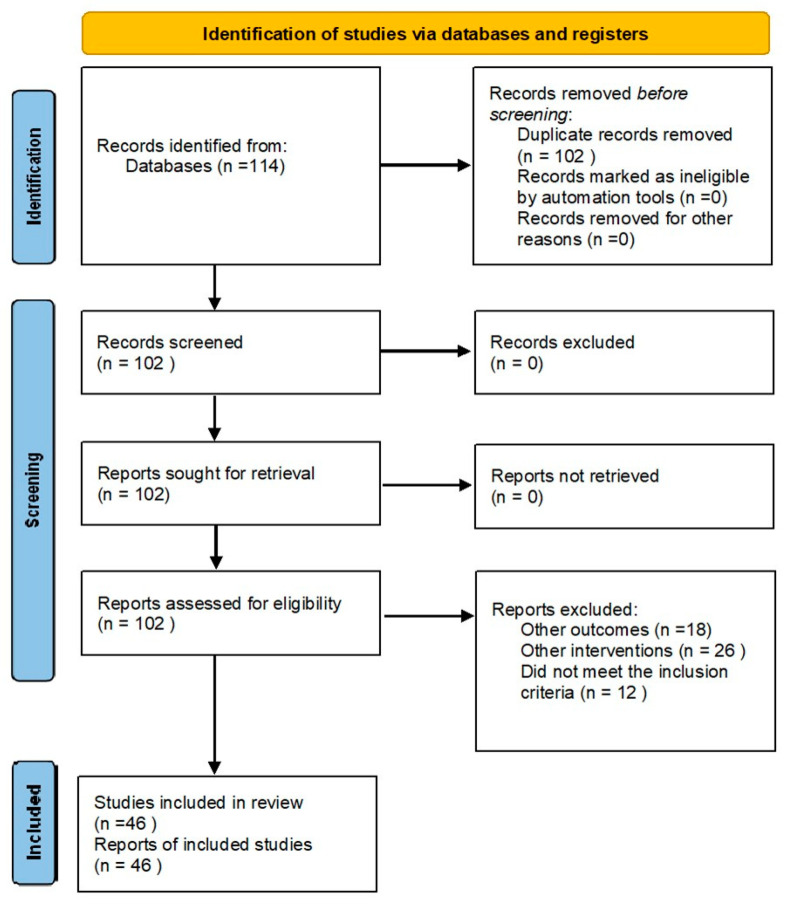

Out of 114 records from the database search, after the removal of duplicates, 102 articles were screened for relevance. A total of 56 articles were excluded, with 45 being deemed irrelevant, and 11 studies lacking full-text availability. Therefore, the total number of articles included in the study was 46:29 articles regarding opportunistic salpingectomy during interventions for benign uterine pathologies, 11 articles related to the effects of tubal surgery on ovarian reserve in stimulation cycles within ART, and 6 articles analyzing the impact of bilateral salpingectomy as a means of surgical sterilization during cesarean section (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, which included searches of databases and registers only.

Regarding the impact of opportunistic salpingectomy on ovarian function, most studies concluded that there is no relationship between the removal of the fallopian tubes and the impairment of ovarian vascularization. Four studies found an association between opportunistic salpingectomy and its negative impact on ovarian reserve: two studies identified a relationship between changes in AMH and FSH levels at 3 months post-intervention, one study highlighted a decrease in AMH levels after hysterectomy (both abdominal and laparoscopic), and the fourth study concluded that there is a connection between bilateral salpingectomy and decreased AMH levels, as well as a decrease in the AFC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Opportunistic salpingectomy during hysterectomy for benign uterine pathologies.

| Study Characteristics | Study Design | Indication | Intervention | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behnamfar et al. [5], 2017 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Benign pathologies of the uterus in premenopause |

Abdominal hysterectomy +/− BS | Mean FSH, LH did not Differ significantly at 6 months postoperatively |

| Nassif et al. [12], 2020 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Benign pathologies | Vaginal hysterectomy | AMH, FSH, AFC, FI, VI, VFI, OvAge No statistically significant differences at 6 and 8 months postoperatively |

| Yuan et al. [13], 2018 |

Prospective longitudinal study | Uterine myoma/Early stage cervical cancer | Laparoscopic/ abdominal hysterectomy with BS | AMH, FSH AMH levels lower and FSH levels higher at 1 week and 6 weeks postoperatively |

| Suneja et al. [14], 2020 |

Observational | Benign pathologies | Abdominal/laparoscopic/vaginal hysterectomy +/− BS | AMH, ovarian Doppler indices(RI, PI, S/Dratio) No significant differences in AMH levels or Doppler indices 3 months post-operatively |

| Rustamov et al. [15], 2016 |

Retrospective cross-sectional | Benign pathologies | Abdominal salpingectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, cystectomy, excision of endometrioma | AMH, AFC, FSH No significant differerence in their levels post-operatively |

| Gareeb et al. [16], 2021 |

Case control | Benign uterine disease | Abdominal hysterectomy +/− BS | FSH, AFC, ovarian volume, RI, PI ovarian artery No significant differences postoperatively or between the groups |

| Abdelazim et al. [17], 2015 |

Prospective | Benign uterine pathology | Abdominal hysterectomy | AMH, FSH, E2, ovarian volume Statistically insignifiant differences in levels/volume at 6 and 12 months after surgery |

| Poonam et al. [18], 2020 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Benign pathologies | Abdominal hysterectomy +/− BS | FSH, LH, E2 BS did not have any negative effect on ovarian function |

| Wang et al. [19], 2021 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Benign uterine diseases in premenopausal women | Laparoscopic hysterectomy +/− OS | AMH, FSH, LH, E2, AFC No differences between the groups at 3 and 9 months postoperatively |

| Findley et al. [20], 2014 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Benign uterine pathologies | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | No difference in AMH levels 4 to 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively |

| Asgari et al. [21], 2018 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Abnormal uterine bleeding related to benign pathology | Total laparoscopic hysterectomy +/− BS | AMH, FSH Significant lower level of AMH and higher level of fSH at 3 months postoperatively |

| Tavana et al. [22], 2021 |

Prospective | Abnormal uterine bleeding without anatomical or hormonal reasons | Total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) compared with Total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) |

AMH levels decreased after both methods, the decrease was greater in TAH |

| Venturella et al. [23], 2016 |

Observational study |

Abnormal uterine bleeding (benign pathologies) |

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy + prophylactic BS | AMH, FSH, AFC, OvAge Without any negative effect on ovarian reserve 3 to 5 years after surgery |

| Naaman et al. [24], 2016 |

Open-label, prospective cohort | Benign uterine pathologies | Abdominal hysterectomy + BS/Fimbriectomy | FSH, AMH, S/D ratio, RI ovarian artery No significant differences between and 6 months after surgery/between groups |

| Venturella et al. [25], 2015 |

Randomized controlled trial |

Uterine myoma and tubal surgical sterilization |

Laparoscopic hysterectomy+BS/BS | AMH, FSH, AFC, VI, FI, VFI Standard vs. wide resection—no difference in ovarian reserve or vascular flow parameters |

| Singh et al. [26], 2023 |

Prospective case control |

Benign pathologies | Abdominal hysterectomy +/−BS | AMH, FSH, LH No statistical significance impact on ovarian reserve |

| Atalay et al. [27], 2016 |

Prospective longitudinal | Benign uterine disorders | TLH + BS vs. TAH + BS | AMH, FSH, LH, E2, inhibin B, ovarian volume AMH and ovarian volume decreased significantly 6 months postoperatively in the TAH-BS group |

Of the six articles analyzed on the topic of the impact of bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian function as a means of surgical sterilization during cesarean section, only two were original articles, while the others were reviews. One of the original articles concluded that serum AMH levels were not significantly different 6–8 weeks post-salpingectomy, while the other additionally analyzed the AFC at 3 and 6 months post-operatively and reached the same conclusion.

Two-thirds of the studies on the potential effects of bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian response in controlled stimulation cycles have drawn attention to the need for increased gonadotropin doses and stimulation days, also highlighting lower fertilization rates and a smaller number of grade 1 embryos. Apparently, there are noticeable decreases in serum AMH, as well as in the AFC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies evaluating response in controlled stimulation cycles and impact on ovarian reserve after salpingectomy.

| Study Characteristics (Year) |

Study Design | Indication | Intervention | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye et al. [7] 2015 |

Retrospective cohort study | Tuboovarian Abscess Ectopic Pregnancy Hydrosalpinx |

Unilateral/Bilateral Salpingectomy | AMH levels lower in the bilateral salpingectomy group (183.48 vs. 127.11, p < 0.037), FSH levels higher in the same group (9.13 vs. 7.85, p = 0.048) |

| Vignarajan et al. [11] 2018 |

Randomized controlled trial | Hydrosalpinx | Bilateral Salpingectomy/ Proximal Tubal Occlusion |

Significant fall in AMH of the salpingectomy group (3.7 vs. 2.6, p < 0.001) and AFC (10.6 vs. 8.6, p < 0.001) Salpingectomy group required higher doses of gonadotropines and more days of stimulation + lower fertilization rates and lower number of grade 1 embryos |

| Huang et al. [28] 2019 |

Retrospective cohort study | Hydrosalpinx | Laparoscopic Salpingectomy | No significant change in AMH, FSH, E2 levels 3 months after surgery |

| Reitz et al. [29] 2023 |

Case-control study | Ectopic Pregnancy Hydrosalpinx |

Unilateral Salpingectomy | Mean number of mature follicles significantly reduced after salpingectomy (3.00 vs. 5.08, p = 0.048) |

| Ho Cheng-Yu et al. [30] 2022 |

Retrospective case-control study | Hydrosalpinx Ectopic Pregnancy |

Unilateral/Bilateral Salpingectomy | AFC and AMH levels statistically significant lower in the salpingectomy group The number of oocytes retrived significantly lower in the same group (10.4 +/− 5.2 vs. 12.2 +/− 3.8, p = 0.06) |

| Yilei H et al. [31] 2023 |

Randomized controlled trial | Hydrosalpinx | Bilateral Salpingectomy | Higher levels of basal FSH in the salpingectomy group and lower AMH levels (p < 0.05) |

| Gluck et al. [32] 2018 |

Retrospective cohort study | Hydrosalpinx Ectopic Pregnancy |

Unilateral/Bilateral Salpingectomy | AMH, FSH, E2, Progesterone levels not significantly different in the groups AFC, oocytes retrieved, amount of Gonadotropin used and number of embryos transferred not significantly different |

4. Discussion

Medeiros et al. first introduced the concept of prophylactic salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention in 2006, which was strongly recommended in subsequent studies. However, concerns regarding post-surgical ovarian function may influence the decision-making process regarding fallopian tube resection during hysterectomy for benign indications [5,12].

This review draws attention to the lack of a consensus in the specialized literature regarding the impact of opportunistic salpingectomy on ovarian function, as there are several studies demonstrating that this intervention has a negative effect on ovarian reserve. This aspect is most clearly illustrated in patients undergoing assisted human reproduction methods, where the treatment response appears to be delayed in those who have undergone bilateral salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx. Moreover, it seems that fertilization rates are lower compared to those who have not undergone this procedure. Most likely, the lack of consensus regarding ovarian function post-salpingectomy resides in the small sample size of studies and the short post-operative follow-up period, which was often limited to 3–6 months post-operatively.

4.1. Opportunistic Salpingectomy during Hysterectomy for Benign Uterine Pathologies

In their study on the effect of bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian function, Tehranian et al. found a significantly decreased serum AMH level at 3 months post-operatively in both groups (p < 0.001) [33]. This finding is consistent with the outcomes reported by Yuan Z et al. (2019), who identified a decreased post-operative AMH level in patients who underwent hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy (p < 0.001). Furthermore, they noted an elevated post-operative FSH level in these patients (p < 0.001). Limitations of this study include the small sample size (84 patients), having a major surgery, and the short follow-up after hysterectomy (only 6 weeks) [13].

Suneja et al. concurred that bilateral opportunistic salpingectomy during hysterectomy does not seem to have any short-term effects on ovarian function or elevate surgical risk [14]. The same opinion is shared by Rustamov et al. in a large cross-sectional study, which failed to identify any statistically significant difference in AMH levels among women who underwent bilateral salpingectomy compared to those who did not undergo this intervention [15]. Another case–control study from 2021 concluded that this procedure is a safe and convenient treatment and it does not have any deleterious effect on ovarian reserve [16]. There have been other studies with the same objectives that reached similar conclusions; however, the longest follow-up of patients was for a period of 1 year, and the patient cohort enrolled was limited in size [17,18].

Concerning the impact of laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian function, Wang et al., Findley et al., and Zahra et al. concluded that there is no statistically significant difference between the two groups [19,20,21]. The retrospective study by Wang et al. showed no significant difference between the salpingectomy group and control group at 3 and 9 months after the intervention, regarding AMH, E2, FSH, and LH levels and AFC (all p > 0.05). Comparing AMH levels between total abdominal hysterectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy, Tavana et al. found a significant decrease in this hormone level after both methods of hysterectomy. However, a lower level of AMH was noted in the total abdominal hysterectomy group [22].

4.2. Salpingectomy at the Time of Cesarean Section

In a study that aimed to compare longitudinal changes in ovarian reserve markers after cesarean section with or without salpingectomy, Ida T et al. noticed that AMH levels increased over 6 months of follow-up in both groups, but no clinically significant difference was observed (baseline 0.69 ng/mL in the control group vs. 0.49 ng/mL in the salpingectomygroup p = 0.64; at 3 months: 1.35 ng/mL vs. 1.45 ng/mL, p = 0.79; at 6 months: 1.74 ng/mL vs. 2.60 ng/mL, p = 0.27). No difference in the Antral Follicle Count was observed [34].

Regarding the optimal sterilization technique during cesarean section, Ganer et al. concluded that bilateral salpingectomy appears to be as safe as tubal ligation, concerning ovarian reserve and intra/post-operative complications [8]. AMH serum levels were not significantly different between the groups 6–8 weeks following surgery. As salpingectomy has the advantage of reducing the risk of ovarian cancer, it could be suggested to patients planning elective cesarean sections [35].

On the other hand, according to Vignarajan et al., PTO (proximal tubal occlusion) is a better surgical technique. In their randomized controlled trial, they observed a notable decline in ovarian reserve parameters following bilateral salpingectomy, with both AMH levels and AFC experiencing a significant decrease (p < 0.001) [8]. A similar conclusion was drawn by three other studies. PTO involved a higher fertilization rate compared to salpingectomy in the treatment of hydrosalpinx in patients before undergoing IVF [36,37,38]. Additionally, both salpingectomy and PTO effectively eliminated the retrograde flow of the toxic hydrosalpinx fluid into the uterine cavity. This resulted in improved access to the ovary, optimalconditions for oocyte retrieval, increased endometrial receptivity, and facilitation of fertilization and pregnancy [11,12,39,40].

Furthermore, salpingectomy performed after ectopic pregnancy in women requiring future ART results in a reduced number of oocytes from the operated adnexa. However, the overall reproductive outcomes do not show a statistically significant difference compared to women who have not undergone salpingectomy [41].

4.3. The Impact of Tubal Surgery on Ovarian Response during Controlled Stimulation Cycles

Xu-ping et al. retrospectively compared serum AMH levels measured on the ovulation induction day in patients with unilateral, bilateral, and no tubal surgery and found a mean AMH level significantly higher in women without tubal surgery, compared to those with bilateral salpingectomy. Also, the FSH level was higher in the group with bilateral salpingectomy with a p-value = 0.048 [7]. Furthermore, Jacob GP et al. concluded in their study that salpingectomy performed after ectopic pregnancy in women requiring future ART results in a reduced number of oocytes from the operated adnexa. However, the outcomes regarding the live births did not show a statistically significant difference compared to women who had not undergone salpingectomy [42].

In a meta-analysis aiming to test the hypothesis that salpingectomy could compromise ovarian function, Mohamed et al. found eight eligible studies (cross-sectional and randomized controlled trials) in which serum AMH and FSH, as well as the AFC, were analyzed post-hysterectomy, myomectomy, and sterilization. Their study found no short-term significant changes in serum AMH but revealed a lower AFC in the salpingectomy group compared to the control group. The limitation of the meta-analysis was the very small number of studies included: only four studies involved salpingectomy during hysterectomy/myomectomy or sterilization, three studies evaluated the impact of salpingectomy on ovarian reserve after ectopic pregnancy, and one study assessed the same impact after salpingectomy for tubal pathology [38].

In another meta-analysis that included five studies, comprising 648 patients, a comparative analysis of AMH, FSH values, and AFC was conducted between patients who underwent proximal tubal occlusion and salpingectomy for treating hydrosalpinx, aiming to evaluate pregnancy rates in ART [43]. The Follicle-Stimulating Hormone values did not differ between the groups, while AMH values and the AFC were significantly higher in the salpingectomy group compared to the proximal tubal occlusion group. Therefore, Shuxie et al. [43] concluded that in the short term, salpingectomy affected ovarian reserve more than proximal tubal occlusion. They found no significant difference in FSH levels between the two techniques, proximal tubal occlusion and laparoscopic salpingectomy, but compared to the salpingectomy group, the PTO group had a significantly higher AFC, both in the 2-month subgroup and overall. Additionally, the PTO group showed significantly higher AMH levels in each specific time subgroup as well as overall.

Although several individual studies with a limited number of cases have demonstrated variable outcomes, a meta-analysis conducted by Mohamed AA et al. in 2017, indicated that salpingectomy has no adverse effects on ovarian reserve [38].

5. Conclusions

Regarding bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy for benign pathologies of the uterus, most studies have not identified any short-term impairment of ovarian function, which is most commonly demonstrated through serum AMH measurement. However, our study identified a lack of consensus concerning the impact on ovarian vascularization following bilateral salpingectomy, as there are some studies cited that show contrary results. As for bilateral salpingectomy as a means of sterilization during cesarean section, the study results are also divergent. Some studies did not identify a statistically significant correlation between this procedure and post-salpingectomy ovarian function, while others, comparing bilateral salpingectomy with proximal tubal occlusion, found a notable decrease in ovarian parameters in the salpingectomy groups, compared to patients who underwent tubal occlusion. The influence of bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian reserve in patients who used assisted human reproduction techniques did not have a major impact. Most studies suggest that this procedure does not negatively affect the outcomes of in vitro fertilization cycles; however, some report that bilateral salpingectomy influenced the number of oocytes retrieved, but not the number of pregnancies achieved.

To conclude, opportunistic salpingectomy seems to have no short-term effect on ovarian function. However, because there is a potential risk of damaging ovarian blood supply during salpingectomy, there is a concern about potential long-term adverse effects on ovarian reserve that need further investigation.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BS | Bilateral salpingectomy |

| OS | Opportunistic salpingectomy |

| EOC | Epithelial ovarian cancer |

| HGSC | High-grade squamous cell |

| STIC | Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| AMH | Anti-Müllerian Hormone |

| FSH | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| AFC | Antral Follicle Count |

| C-section | Cesarean section |

| PTO | Proximal tubal occlusion |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| OvAge | Ovarian age |

| RI | Ovarian artery resistance index |

| PI | Ovarian artery pulsatility index |

| S/D | Systolic/diastolic ratio ovarian artery |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R. and C.M.; methodology, T.R.; investigation, T.R.; resources, M.M. and V.T.; data curation, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, T.R., M.M., V.T. and C.M.; visualization, M.M. and V.T.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, T.R.; funding acquisition, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Târgu Mures, Research, Grant number 171/09.01.2024.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Menon U., Karpinskyj C., Gentry-Maharaj A. Ovarian Cancer Prevention and Screening. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;131:909–927. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daly M., Dresher C., Yates M., Jeter J., Karlan B., Alberts D., Lu K. Salpingectomy as a means to reduce ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Prev. Res. 2015;8:342–348. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelderblom M.E., IntHout J., Dagovic L., Hermens R.P., Piek J.M., de Hullu J.A. The effect of opportunistic salpingectomy for primary prevention of ovarian cancer on ovarian reserve a systematic review and metaanalysis. Maturitas. 2022;166:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2022.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darelius A., Lycke M., Kindblom J., Kristjansdottir B., Sundfeldt K., Strandell A. Efficacy of salpingectomy at hysterectomy to reduce the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: A systematic review. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017;124:880–889. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behnamfar F., Jabbari H. Evaluation of ovarian function after hysterectomy with or without salpingectomy: A feasible study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2017;22:68. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_81_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon J.S. Ovarian cancer risk reduction through opportunistic salpingectomy. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015;26:83–86. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2015.26.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye X., Yang Y., Sun X. A retrospective analysis of the effect of salpingectomy on serum antiMüllerian hormone level and ovarian reserve. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;212:53.e1–53.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ely L., Troung M. The Role of Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy vs Tubal Occlusion or Ligation for Ovarian Cancer Prophylaxis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roeckner J.T., Sawangkum P., Sanchez-Ramos L., Duncan J.R. Salpingectomy at the time of Cesarean Delivery—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;135:550–557. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganer Herman H., Gluck O., Keidar R., Kemer R., Kovo M., Levran D., Bar J., Sagiv R. Ovarian reserve Following Cesarean-delivery with Salpingectomy Versus Tubal Ligation—A Randomized Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;217:472.e1–472.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vignarajan C., Malhotra N., Singh N. Ovarian Reserve and Assisted Reproductive Technique Outcomes After Laparoscopic Proximal Tubal Occlusion or Salpingectomy in Women with Hydrosalpinx Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:1070–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nassif A., Elnory M.A. Impact of prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian reserve in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Evid. Based Womens Health J. 2020;10:150–161. doi: 10.21608/ebwhj.2020.22949.1074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Z., Cao D., Bi X., Yu M., Yang J., Shen K. The effects of hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian reserve. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019;145:233–238. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suneja A., Garg A., Bhatt S., Guleria K., Madhu S.V., Sharma R. Impact of Opportunistic Salpingectomy on Ovarian Reserve and Vascularity in Patients Undergoing Hysterectomy. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020;18:107. doi: 10.1007/s40944-020-00455-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rustamov O., Krishnan M., Roberts S.A., Fitzgerald C.T. Effect of salpingectomy, ovarian cystectomy and unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy on ovarian reserve. Gynecol. Surg. 2016;13:173–178. doi: 10.1007/s10397-016-0940-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gareeb M.A., El-sayed Mohamed M.L., Lashin H.A., El-Bakri M.A. Impact of Total Salpingectomy Versus Tubal Conservation During Abdominal Hysterectomy on Ovarian Function. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2021;85:3980–3984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdelazim I.A., Abdelrazak K.M., Elbiaa A.A., Farghali M.M., Essam A., Zhurabekova G. Ovarian function and ovarian blood supply following premenopausal abdominal hysterectomy. Przegląd Menopauzalny. 2015;14:238–242. doi: 10.5114/pm.2015.56312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poonam L., Ranjeet M., Urvashi M., Anil L., Shalini G., Kadam V.K. Comparative Study of Ovarian Function in Patients Undergoing Hysterectomy With or Without Bilateral Complete Salpingectomy. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020;18:38. doi: 10.1007/s40944-020-00418-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S., Gu J. The effect of prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian reserve in patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy. J. Ovarian Res. 2021;14:86. doi: 10.1186/s13048-021-00825-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Findley A.D., Siedhoff M.T., Hobbs K.A., Steege J.F., Carey E.T., McCall C.A., Steiner A.Z. Short-term effects of salpingectomy during laparoscopic hysterectomy on ovarian reserve: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2014;100:1704–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asgari Z., Tehranian A., Rouholamin S., Hosseini R., Sepidarkish M., Rezainejad M. Comparing surgical outcome and ovarian reserve after laparoscopic hysterectomy between two methods of with and without prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018;14:543–548. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.193114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tavana Z., Askary E., Poordast T., Soltani M., Vaziri F. Does laparoscopic hysterectomy + bilateral salpingectomy decrease the ovarian reserve more than total abdominal hysterectomy? A cohort study, measuring anti-Müllerian hormone before and after surgery. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:329. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01472-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venturella R., Lico D., Borelli M., Imbrogno M.G., Cevenini G., Zupi E., Zullo F., Morelli M. 3 to 5 years later: Long-term Effects of Prophylactic Bilateral Salpingectomy on Ovarian Function. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.08.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naaman Y., Hazan Y., Gillor M., Marciano G., Bardenstein R., Shoham Z., Ben-Arie A. Does the addition of salpingectomy or fimbriectomy to hysterectomy in premenopausal patients compromise ovarian reserve? A prospective study. Eur. J. Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venturella R., Morelli M., Lico D., Di Cello A., Rocca M., Sacchinelli A., Mocciaro R., D’Alessandro P., Maiorana A., Gizzo S., et al. Wide excision of soft tissues adjacent to the ovary and fallopian tube does not impair the ovarian reserve in women undergoing prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy: Results from a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1332–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh N., Srivastava S., Singh N., Ali W. Impact of ovarian disease on fertility reserve as assessed through serum AMH levels in reproductive age women. J. Endom Uterine Dis. 2023;4:10051. doi: 10.1016/j.jeud.2023.100051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atalay M.A., Demir B.C., Ozerkan K. Change in the ovarian environment after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy: Is it the technique or surgery itself? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod Biol. 2016;204:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.07.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang D., Zhu Y., Chen J., Zhang S. Effect of modified laparoscopic salpingectomy on ovarian reserve: Changes in the serum antimüllerian hormone levels. Laparosc. Endoscop Robotic Surg. 2019;2:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lers.2019.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reitz L., Balaya V., Pache B., Feki A., Le Conte G., Bennamar A., Ayoubi J.M. Ovarian Follicular Response Is Altered by Salpingectomy in Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Pre- and Postoperative Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023;12:4942. doi: 10.3390/jcm12154942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho C.Y., Chang Y.Y., Lin Y.H., Chen M.J. Prior salpingectomy impairs the retrieved oocyte number in in vitro fertilization cycles of women under 35 years old without optimal ovarian reserve. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0268021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yilei H., Shuo Y., Caihong M., Yan Y., Xueling S., Jiajia Z., Ping L., Rong L., Jie Q. The influence of timing of oocytes retrieval and embryo transfer on the IVF-ET outcomes in patients having bilateral salpingectomy due to bilateral hydrosalpinx. Front. Surg. 2023;9:1076889. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1076889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gluck O., Tamayev L., Torem M., Bar J., Raziel A., Sagiv R. The impact of salpingectomy on Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels and Ovarian Response of In Vitro Fertilization Patients. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2018;20:509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tehranian A., Zangbar R., Aghajani F., Sepidarkish M., Rafiei S., Esfidani T. Effects of salpingectomy during abdominal hysterectomy on ovarian reserve: A randomized controlled trial. Gynecol. Surg. 2017;14:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s10397-017-1019-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ida T., Fujiwara H., Taniguchi Y., Kohyama A. Longitudinal assessment of anti-Müllerian hormone after cesarean section and influence of bilateral salpingectomy on ovarian reserve. Contraception. 2021;103:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masouleh T.Z., Etchegary H., Hodgkinson K., Wilson B.J., Dawson L. Beyond Sterilization: A comprehensive Review on the Safety and Efficacy of Opportunistic Salpingectomy as a Preventative Strategy for Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2023;30:10152–10165. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30120739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng K.Y.B., Cheong Y. Hydrosalpinx—Salpingostomy, salpingectomy or tubal occlusion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019;59:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Arpe S., Franceschetti S., Caccetta J., Pietrangeli D., Muzii L., Panici P.B. Management of hydrosalpinx before IVF: A literature review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015;35:547–550. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2014.985768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohamed A.A., Yosef A.H., James C., Al-Hussaini T.K., Bedaiwy M.A., Amer S. Ovarian reserve after salpingectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017;96:795–803. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotlyar A., Gingold J., Shue S., Falcone T. The effect of salpingectomy on ovarian function. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:563–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong X., Ding W.B., Yuan R.F., Ding J.Y., Jin J. Effect of interventional embolization treatment for hydrosalpinx on the outcome of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Medicine. 2018;97:e13143. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo J., Shi Y., Liu D., Yang D., Wu J., Cao L., Geng L., Hou Z., Lin H., Zhang Q., et al. The effect of salpingectomy on the ovarian reserve and ovarian response in ectopic pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98:e17901. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacob G.P., Oraif A., Power S. When helping hurts: The effect of surgical interventions on ovarian reserve. Hum. Fertil. 2016;19:3–8. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2016.1148826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shuxie W., Zhang Q., Li Y. Effect comparison of salpingectomy versus proximal tubal occlusion on ovarian reserve. Medicine. 2020;99:e20601. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.