Abstract

Lemierre's syndrome can be fatal if diagnosed late or not treated appropriately. We herein report a 40-year-old woman with a fever and pain with tenderness in her palms after the administration of antibiotics for pharyngotonsillitis. She was diagnosed with Lemierre's syndrome, and her symptoms improved after the administration of intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam. In this case, the palmar lesions indicated septic emboli and were an important finding in recognizing Lemierre's syndrome. Lemierre's syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with a persistent fever following oropharyngeal infection, even if they have received antimicrobial therapy, resolved pharyngeal symptoms, and negative culture results.

Keywords: Lemierre's syndrome, palmar lesion, septic emboli, abscess

Introduction

Lemierre's syndrome is characterized by bacterial or viral oropharyngeal infection, followed by sepsis, internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis, and septic emboli at remote sites (1). The annual incidence of Lemierre's syndrome is estimated to be 3-6 cases per million people, but it is more common in young adults than in others, with an annual incidence of 14.4 cases per million people 14-24 years old (1).

Lemierre's syndrome can be fatal if diagnosed late or if not treated appropriately. The lung is the site most commonly affected by distant septic emboli, which are present in the lungs in approximately 80% of cases (2). Other sites involved may include the soft tissue, muscle, spleen, liver, kidney, and brain (1).

We herein report a woman who developed Lemierre's syndrome with a palmar lesion and discuss the clinical significance of palmar lesions in the prompt and accurate diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome.

Case Report

A 40-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with fever and pain in the palms, legs, and right shoulder. Seventeen days previously, she had experienced a sore throat and fever and visited a nearby clinic. On examination, her posterior pharyngeal wall and left palatine tonsillar area showed redness and swelling, with white patches. She was diagnosed with acute pharyngotonsillitis and received oral azithromycin for three days (Fig. 1). The pain in her throat eased slightly, but her fever persisted, and she received lascufloxacin for 5 days, 3 days after the initial clinic visit. However, her body temperature increased further and she developed tenderness and pain in her palms the following day. She had no previous medical history of notes, had not received any dental procedures, or used any injection drugs.

Figure 1.

The clinical course in this case. ABPC/SBT: ampicillin-sulbactam, AMPC/CVA: amoxicillin-clavulanate, AZM: azithromycin, CRP: C-reactive protein

On admission, her body temperature was 37.2°C, and her blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation levels were normal. A physical examination revealed swelling and tenderness of the left palm (Fig. 2), a restricted range of motion in the right shoulder, and subcutaneous induration in the legs but no tenderness in her neck. Auscultation of the chest showed no heart murmur. She did not complain of any difficulties with movement or abnormal sensations in the hands. There were no other skin signs, such as Osler nodes or Janeway lesions. Laboratory results revealed an increased white blood cell count (21,300 /μL), with an increased neutrophil fraction (89.1%) and elevated C-reactive protein (23.3 mg/dL) and D-dimer (10.8 μg/mL) levels. The β-D-glucan level was normal (6.2 pg/mL). Cryptococcus antigens and tuberculosis-specific enzyme-linked immunospot assay (T-SPOTⓇ.TB) were negative. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed thrombosis in the left internal jugular vein (Fig. 3), slightly enlarged lymph nodes near the left accessory nerve, cavitary lung lesions (Fig. 4A), and intramuscular abscesses with ring enhancement in the right shoulder (Fig. 4B) and leg. No masses suggestive of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations were identified, and no abnormalities were found in the kidneys, liver, or spleen. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left hand revealed a high-intensity lesion in the palm during short tau inversion recovery (Fig. 5A). The lesion also appeared to be an abscess with ring enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequence (Fig. 5B).

Figure 2.

A photograph of the left hand of a 40-year-old woman showing significant swelling and redness in the palmar region.

Figure 3.

Axial (Panel A), coronal (Panel B), and sagittal (Panel C) contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the neck showing a filling defect of the left internal jugular vein (arrows).

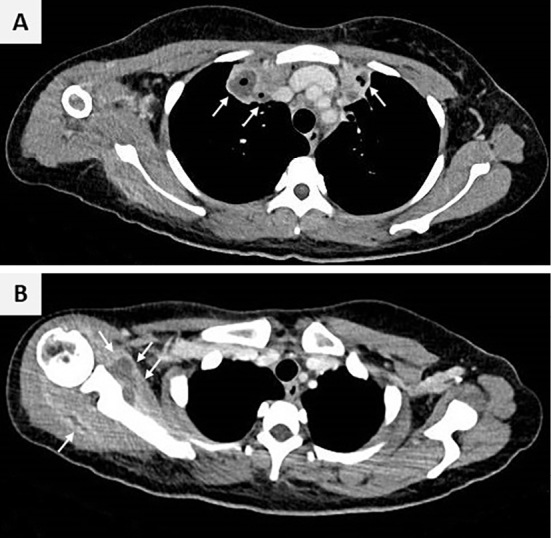

Figure 4.

Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest showing bilateral cavitary lung lesions with internal necrosis (arrows, Panel A) and intramuscular abscesses with ring enhancement around the scapula (arrows, Panel B).

Figure 5.

Axial magnetic resonance imaging of the left hand showing a high-intensity area in the thenar subcutaneous region on short tau inversion recovery (arrows, Panel A) and ring enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequence (arrows, Panel B), suggesting subcutaneous abscess.

We suspected a bloodstream infection because the imaging suggested the presence of multiple abscesses and performed blood and sputum cultures. Echocardiography revealed no vegetation, valvular disorder, atrial and ventricular septal defects, or patent foramen ovale. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the head revealed no intracranial abnormalities. In addition, we performed bronchoscopy to collect bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, shoulder arthrocentesis, and puncture the palmar lesion and submitted the samples for culture. The cultures tested negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. A transbronchial lung biopsy revealed an inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting mainly of neutrophils; however, no organisms were detected.

The patient's anti-streptolysin-o antibody (ASO) level, which was normal [205 (normal: <240) IU/mL] 9 days before admission, was markedly elevated (5,620 U/mL) on admission. Based on a history of acute pharyngotonsillitis, multiple abscesses, thrombosis in the internal jugular vein, and a high ASO titer, Lemierre's syndrome was diagnosed following streptococcal infection. The patient was administered intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam. Her symptoms gradually improved, and contrast-enhanced CT on day 26 of hospitalization revealed that all of the lesions had disappeared. The antibiotic was switched to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the patient was discharged on day 32 of hospitalization.

Discussion

In 1936, Lemierre described postanginal septicemia caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum complicated by internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis and distant septic emboli (3). This condition later became known as Lemierre's syndrome. The pathogenesis of Lemierre's syndrome is thought to be due to the invasion of bacteria from the pharyngeal mucosa damaged by the preceding bacterial or viral pharyngitis. Bacteria reach the lateral pharyngeal space and cause thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, which results in the formation of septic emboli and abscesses in remote organs (1).

Thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein extends hematogenously through the right heart system to the lungs, resulting in a high incidence of pulmonary involvement in Lemierre's syndrome. Peripheral involvement is infrequent, occurring in less than 3% of cases (4). In right-sided infective endocarditis, a similar hematogenous route leads to disseminated disease, with pulmonary embolism occurring frequently, but peripheral embolic symptoms are infrequent (5). Thus, the low frequency of peripheral lesions, including palmar involvement, in Lemierre's syndrome may be related to the hematogenous extension of distant lesions. To our knowledge, only one case of Lemierre's syndrome with palmar lesions has been previously reported (6). In the previous case, abscesses were identified in the shoulder, lung, and pericardium, whereas pain was localized to the hand, as in this case. This suggests that the palmar region is not only a candidate site for abscesses but also an important clue to suspect Lemierre's syndrome. Skin and soft tissue lesions in Lemierre's syndrome present as pustules, subcutaneous abscesses, and necrotic lesions (4). However, similar lesions may also be caused by other infections. Palmar abscesses commonly arise from penetrating trauma and animal bites (7). Consequently, if symptoms are localized to the palms, Lemierre's syndrome may be overlooked and treated as a local infection. Lemierre's syndrome should be considered in patients with palmar lesions in which other causative factors, such as trauma, are absent based on the patient's medical history, particularly if the palmar symptoms are preceded by pharyngeal infection. If Lemierre's syndrome is suspected, the presence of systemic septic emboli should be confirmed using imaging studies.

The diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome is based on the presence of deep neck infection, followed by sepsis, internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis, and septic emboli at remote sites (8). Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for detecting internal jugular vein thrombosis and distant lesions (1). In this case, the main symptom was pain in the extremities, which mimicked arthritis. If CT had not been performed, the patient could have been misdiagnosed with post-streptococcal reactive arthritis based on the high ASO titer and was treated with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents. In our case, CT helped identify asymptomatic internal jugular vein thrombosis and pulmonary lesions, in addition to painful lesions. Therefore, systemic investigation is important if Lemierre's syndrome is suspected. MRI is also useful for detecting epidural and brain abscesses associated with Lemierre's syndrome (1). Furthermore, this case suggests that MRI can be useful for identifying foci of inflammation in subcutaneous tissues, tendons, and joints when soft tissue lesions are present in a limited area, such as the left palm in our patient.

Sinave et al. (9) proposed four criteria that must be met for the diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome: 1) prior infection of the mid-pharynx, 2) at least one positive blood culture, 3) thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, and 4) at least one distant site of infection (9). In this case, we cultured samples from various sites where lesions were present; however, all cultures were negative. Therefore, this case did not meet the criteria proposed by Sinave et al. (9) and cannot be classified as classic Lemierre's syndrome (9). However, there are no standard diagnostic criteria for Lemierre's syndrome, and some definitions do not require positive blood culture (2,4,10). In the present case, the blood culture was negative, probably because of prior antibiotic administration but met the other three clinical criteria proposed by Sinave et al. (9) Therefore, we diagnosed this case as Lemierre's syndrome based on a broader definition. In this case, the ASO level was normal when the patient developed pharyngotonsillitis but was markedly elevated on admission. ASO is an antibody against streptolysin-O, a hemolytic toxin produced by beta-hemolytic streptococci, and typically rises approximately one week after streptococcal infection, peaking at approximately three to five weeks. In this case, azithromycin and lascufloxacin were administered before admission, and the pharyngotonsillitis improved on admission. Therefore, we concluded that the pharyngitis was caused by Streptococcus. However, the persistence of a fever, as well as the symptoms on the palms, right shoulder, and legs, suggest that Lemierre's syndrome may have been caused by other bacteria that were refractory to the initial antimicrobial agents. The most frequent causative agent of Lemierre's syndrome is F. necrophorum, which is resistant to macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines. In addition, some strains of F. necrophorum produce β-lactamases (11). Consequently, an antibiotic regimen that includes β-lactamase inhibitors is recommended. Lemierre's syndrome should be considered in patients with recent pharyngitis with a persistent fever, even if they have been treated with antibiotics, and the pharyngeal symptoms have resolved.

In addition to prompt and appropriate antimicrobial therapy, surgical drainage may be required to treat Lemierre's syndrome. In the present case, the patient had a palmar lesion with severe swelling and tenderness. The hand is anatomically divided into several compartments. Various factors, such as trauma, burns, abscess, and reperfusion injury, can increase intracompartmental pressure (12). If this condition persists, it can lead to significant functional impairment owing to neuromuscular necrosis, a condition known as compartment syndrome. In our case, although localized swelling and pain were present, there were no signs of motor or sensory impairments in the hand. We concluded that compartment syndrome was unlikely, observed the symptoms carefully, and treated the patient with ampicillin-sulbactam without additional treatment, such as debridement or other surgical procedures.

A review of 114 cases of Lemierre's syndrome reported a case fatality rate of 5% (13). In another review, all cases that did not receive antimicrobial therapy within 12 days of the onset resulted in death (4). Therefore, the prognosis of Lemierre's syndrome may be better if antibacterial treatment and surgical procedures are initiated early. Lemierre's syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis of multiple abscesses, including palmar abscesses, following pharyngitis, as seen in this case.

In conclusion, this case suggests that palmar lesions can be a sign of septic emboli in Lemierre's syndrome and provides an important clue to the diagnosis. Lemierre's syndrome should be considered in patients with a persistent fever following oropharyngeal infection, even if they have a history of antimicrobial therapy, resolved pharyngeal symptoms, and negative blood culture results.

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Lee WS, Jean SS, Chen FL, Hsieh SM, Hsueh PR. Lemierre's syndrome: a forgotten and re-emerging infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 53: 513-517, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 81: 458-465, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemierre A. On certain septicemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet 227: 701-703, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riordan T. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre's syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev 20: 622-659, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 111: e394-e434, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braunbeck A, Geiger EV, Weber R, et al. Hohlhandphlegmone als erstmanifestation des Lemierre-syndroms [Phlegmon of the palm of the hand as initial manifestation of the Lemierre syndrome]. Unfallchirurg 113: 155-158, 2010. (German. Abstract in English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koshy JC, Bell B. Hand infections. J Hand Surg Am 44: 46-54, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong AW, Spooner K, Sanders JW. Lemierre's Syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2: 168-173, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinave CP, Hardy GJ, Fardy PW. The Lemierre syndrome: suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to oropharyngeal infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 68: 85-94, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg NA, Knapp-Clevenger R, Hays T, Manco-Johnson MJ. Lemierre's and Lemierre's-like syndromes in children: survival and thromboembolic outcomes. Pediatrics 116: e543-e548, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook I. Infections caused by beta-lactamase-producing Fusobacterium spp. in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 12: 532-533, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oak NR, Abrams RA. Compartment syndrome of the hand. Orthop Clin North Am 47: 609-616, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karkos PD, Asrani S, Karkos CD, et al. Lemierre's syndrome: a systematic review. Laryngoscope 119: 1552-1559, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]