Abstract

Folate enzymes, namely, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and pteridine reductase (PTR1) are acknowledged targets for the development of antiparasitic agents against Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis. Based on the amino dihydrotriazine motif of the drug Cycloguanil (Cyc), a known inhibitor of both folate enzymes, we have identified two novel series of inhibitors, the 2-amino triazino benzimidazoles (1) and 2-guanidino benzimidazoles (2), as their open ring analogues. Enzymatic screening was carried out against PTR1, DHFR, and thymidylate synthase (TS). The crystal structures of TbDHFR and TbPTR1 in complex with selected compounds experienced in both cases a substrate-like binding mode and allowed the rationalization of the main chemical features supporting the inhibitor ability to target folate enzymes. Biological evaluation of both series was performed against T. brucei and L. infantum and the toxicity against THP-1 human macrophages. Notably, the 5,6-dimethyl-2-guanidinobenzimidazole 2g resulted to be the most potent (Ki = 9 nM) and highly selective TbDHFR inhibitor, 6000-fold over TbPTR1 and 394-fold over hDHFR. The 5,6-dimethyl tricyclic analogue 1g, despite showing a lower potency and selectivity profile than 2g, shared a comparable antiparasitic activity against T. brucei in the low micromolar domain. The dichloro-substituted 2-guanidino benzimidazoles 2c and 2d revealed their potent and broad-spectrum antitrypanosomatid activity affecting the growth of T. brucei and L. infantum parasites. Therefore, both chemotypes could represent promising templates that could be valorized for further drug development.

Keywords: antiparasitic agents, dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors, pteridine reductase inhibitors, triazino and guanidino benzimidazoles, Trypanosoma brucei, Leishmania infantum

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT, also known as sleeping sickness) belongs to the group of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) which affect about one billion people worldwide1 and cause significant morbidity and mortality in humans and animals.2 Two subspecies of parasite cause different disease courses in humans: Trypanosoma brucei gambiense is responsible for the chronic and slow-progressing form of the disease, while Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense establishes an acute, faster-progressing, and multiorgan illness.3 To date, control programs have considerably reduced the occurrence of HAT, although it still represents a public health concern until its complete elimination is reached. World Health Organization (WHO) has set this achievement for 2030,4,5 asking for cooperation among multiple sectors, on the basis of the One Health approach.

Only six drugs are in clinics for HAT, whose indications for use depend on the stage of the infection, i.e., melarsoprol, suramin, pentamidine, eflornithine, nifurtimox/eflornithine, and the most recent fexinidazole.6,7 However, the lack of effective treatment due to the toxicity and resistance phenomena are the main hurdles and have prompted researchers to seek more efficacious, safe, and unexpensive drugs.8,9 Along with T. brucei, the Trypanosomatidae family includes T. cruzi and Leishmania parasites which are the etiologic agents of Chagas disease and leishmaniasis, respectively. The diseases caused by these protozoa are a major public health problem in many parts of the world and call for the need of renovating the arsenal of medications, being still restricted to quite obsolete solutions.10,11

In recent years, targeting the enzymes of folate metabolism was demonstrated to be a successful strategy also for the treatment of parasitic infections such as Malaria, Leishmaniasis, and Trypanosomiasis.12−14 Two enzymes, namely, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and pteridine reductase 1 (PTR1), can provision the parasite of reduced folate (tetrahydrofolate, THF), a crucial cofactor in the synthesis of de novo nucleobases and certain amino acids to sustain its proliferation. DHFR is the primary enzyme in the folate path, while PTR1 participates for about 10%; when DHFR is inhibited, e.g., by the antifolate drug methotrexate (MTX), the amplification of both DHFR and PTR1 genes occurs to supply the parasite of folate metabolites.15,16 Further investigations are in due course to incorporate more in-depth knowledge about the fine interplay between the two enzymes and the respective pathway connection. In contrast to humans, trypanosomatids express the DHFR as a homodimer comprising thymidylate synthase (bifunctional DHFR-TS), which catalyzes the reductive methylation of deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to thymidylate (dTMP) for DNA synthesis and repair. Notably, a recent study reinforced the druggability of TbTS and, concurrently, the development of TbTS inhibitors, from the observation that the anticancer drug nolatrexed, a known inhibitor of human TS (hTS, Ki = 15 nM), similarly inhibited TbTS (Ki = 39.4 nM) and the growth of parasites (EC50 ∼ 32 μM, as the mean value from four diverse culture media).17

Folate-dependent enzymes have gained a lot of attention as the valued targets for addressing new treatments for HAT9,14,18,19 and, despite numerous efforts, a moderate antiparasitic effect was observed for the distinct chemotypes developed so far, while demonstrating nanomolar potency against one of these two enzymes. Therefore, these findings support the concept that both PTR1 and DHFR should be targeted simultaneously and, possibly, to an equal extent.13,15,20

Monocyclic and bicyclic aromatic systems such as pyrimidines, pteridines, quinolines, pyrrolo-pyrimidines, benzimidazoles, and benzothiazoles, mimicking the substrate pterin moiety, were extensively studied as molecular scaffolds for the design of TbPTR1 and TbDHFR inhibitors.13,21−24 Also, the antimalarial drug cycloguanil (Cyc) (Figure 1a), featured by a dihydrotriazine core, was found to target TbPTR1 besides Plasmodial and Trypanosoma DHFR.25 Interestingly, Cyc exhibited a superior affinity for TbDHFR (Ki = 256 nM26) than TbPTR1 (IC50 = 31.6 μM25) and a low antiparasitic effect against T. brucei (EC50 > 25 μM26). Conversely, some structurally related analogues of Cyc (Figure 1b), where the 4-Cl atom on the phenyl ring and/or the gem-dimethyl groups at C(6) were modified, showed an opposite trend of selectivity more favorable for TbPTR1 than TbDHFR.27 In particular, a 4-OCH3 on the phenyl ring (TbDHFR IC50 = 33.2 μM, TbPTR1 IC50 = 0.67 μM) and a bulky spiro-cyclohexyl moiety on C(6) (TbDHFR IC50 = 17.6 μM, TbPTR1 IC50 = 1.22 μM) improved the inhibitory performance against TbPTR1 with respect to the prototype Cyc. These data suggested that the enzyme catalytic cavity could also accommodate more expanded molecular cores. The 2,4-diamino pyrimido[4,5-b]indole derivative (PI) (Figure 1b) was described as the first tricyclic compound targeting TbPTR1 (Ki of 83 μM). In the complex with the enzyme, it unveiled an interaction network similar to pyrimethamine (Pyr) (Figure 1a) and Cyc, but it formed additional contacts within the hydrophobic pockets placed nearby in the catalytic site of TbPTR1.21

Figure 1.

(a) Antiprotozoal drugs Cyc and Pyr, as template molecules targeting TbDHFR and TbPTR1; (b) previously studied TbPTR1 inhibitors characterized by a key substitution on the core structure of Cyc or by a pyrimidine-based tricyclic scaffold (PI).

Following the above consideration, in the present paper, we describe the design and synthesis of a new library of 2-aminotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazoles and 2-guanidinobenzimidazoles. The biological profiling of the conceived set first included the evaluation of their on-target activities (TbPTR1 and TbDHFR). Then, we reasoned to examine the activity against TbTS, considering the potential risk of toxic effects as a consequence of a 60% sequence identity to its human ortholog and an active site showing an identical amino acid sequence.18 To estimate the toxicity and species-specificity preferences of the library, the human DHFR (hDHFR) and hTS inhibitions were then assessed. Most of the title compounds were assayed for their ability to inhibit T. cruzi and L. major DHFR enzymes with the aim of developing broad-spectrum antiprotozoan agents. The structures of TbPTR1 and TbDHFR were solved in complex with selected inhibitors and compared with those of Pyr and Cyc to explain the structure–activity relationships of these new compound series. Finally, the antiparasitic effect (EC50) of both series was evaluated against T. brucei brucei and L. infantum promastigotes and the toxicity (CC50) against THP-1 human macrophages as a representative model of the host defense immune response against parasite infection.

Result and Discussion

Design of the Compounds

Evidence from the literature provides several cocrystal structures of TbPTR1 with distinct molecules, while only few examples of TbDHFR–inhibitor complexes are resolved. While for the known drug Pyr the complexes with both enzymes are released, for Cyc only that with TbPTR1 is available. The two antifolate drugs differ in the chemical structure of the core, i.e., the pyrimidine ring of Pyr and the nonaromatic 1,6-dihydrotriazine ring of Cyc. They adopt similar binding modes within the TbPTR1 active site, entailing the same network of H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions,27 as discussed below. Therefore, the structures of DHFR and PTR1 complexes with Pyr were chosen as template models for the design of the novel compound’s library, and the derived information was used for the purpose of a meaningful comparison.

Despite DHFR and PTR1 performing analogous catalytic reactions, recognizing the same substrates, their active sites are structurally distinct and exhibit only a little consensus. Moreover, the comparison between the structures of their complexes with Pyr has allowed the identification of the main structural determinants responsible for common interactions toward both enzymes.

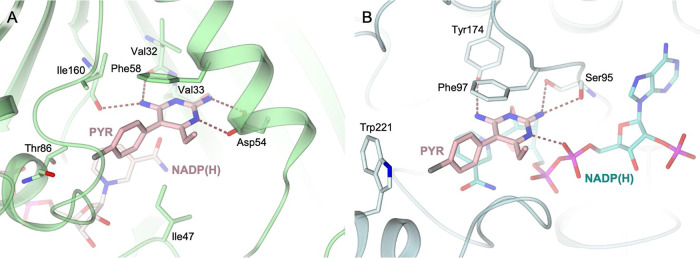

In TbDHFR, the binding of Pyr is stabilized through a network of H-bonds entailed with Val32 (backbone carbonyl group) and Ile160 (backbone carbonyl group), on one side, and with Asp54, on the other (Figure 2A). The inhibitor is further stabilized by van der Waals contacts with Ile47, Phe58, and Ile160 and by a halogen bond with Thr86. In TbPTR1, Pyr binds inside the peculiar π-sandwich lined by the cofactor nicotinamide and the aromatic side chain of Phe97 (Figure 2B). Inside the catalytic cavity, the inhibitor is further stabilized by the H-bonds entailed with Ser95 (hydroxyl and backbone carbonyl groups), Tyr174 (hydroxyl group), and the cofactor (ribose hydroxyl and β-phosphate groups) and by the halogen bond with Trp221 (indole moiety).

Figure 2.

Active site view of the complexes (A) TbDHFR-NADP(H) (light green cartoon and carbons; cofactor in sticks, light pink carbons) and Pyr (in sticks, pink carbons), PDB id 3QFX;26 (B) TbPTR1-NADP(H) (light cyan cartoon and carbons; cofactor in sticks, cyan carbons) and Pyr (in sticks, pink carbons), PDB id 7OPJ.27 In both panels, oxygen atoms are colored red, nitrogen blue, sulfur yellow, and phosphorus magenta. H-bonds are shown as tan dashed lines.

On the wave of these findings, we considered it interesting to synthesize a novel set of compounds (Table 1), the 2-aminotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazoles (1a–g), that were obtained through the scaffold hopping manipulation of Cyc, leading to a new tricyclic system where the key amino dihydrotriazine motif of Cyc was integrated with the benzimidazole ring. Noteworthy, benzimidazole is regarded as a “privileged structure” in heterocyclic chemistry due to its association with a wide range of biological activities.28,29 In the field of antiprotozoan agents, it recurs in several examples as the primary unit or meaningful substructure.30−32

Table 1. Chemical Structures of the Compound’s Library (1a–g and 2a–g) Investigated as Antiprotozoal Agents.

| triazino

benzimidazoles |

2-guanidino

benzimidazoles |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| comp. | R | comp. | R |

| 1a | H | 2a | H |

| 1b | 7(8)-Cl | 2b | 5(6)-Cl |

| 1c | 7,8-diCl | 2c | 5,6-diCl |

| 1d | 7,9-diCl | 2d | 4,6-diCl |

| 1e | 7(8)-CF3 | 2e | 5(6)-CF3 |

| 1f | 7(8)-OCH3 | 2f | 5(6)-OCH3 |

| 1g | 7,8-diCH3 | 2g | 5,6-diCH3 |

Further, their open ring analogues, the 2-guanidino benzimidazoles 2a–g, were included in the study, as pseudoring structures that may exhibit some conformational analogy with 2-aminotriazino benzimidazoles owing to a greater flexibility.

The novel chemotypes were decorated with a Cl atom, as in PYR (Figure 2) and CYC, with a view to preserving the ability of the prototypes to entail a halogen bond with the respective amino acid residues (Thr86 and Trp221) of the TbDHFR and TbPTR1 active sites. Besides exploring the lipophilic CF3 and CH3 groups on the aromatic ring, which are reciprocally characterized by an opposite inductive electronic effect, the polar and electron-donor OCH3 group was also considered (Table 1), since it previously demonstrated to improve the inhibition of TbPTR1 when replacing the 4-Cl atom of Cyc27 (Figure 1).

Chemistry

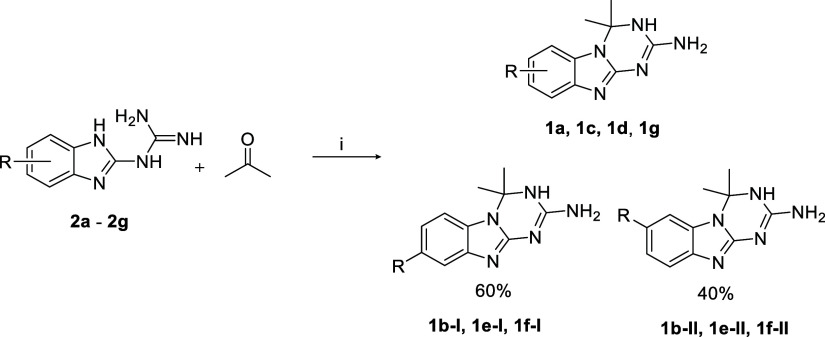

The 2-guanidino benzimidazoles 2a–g were synthesized by reacting the proper 1,2-phenylendiamine with dicyandiamide in acid-catalyzed conditions (Scheme 1), while their respective 2-aminotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole derivatives of series 1 were achieved through a ring annellation reaction of series 2 with acetone under piperidine catalysis (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1. Reagents and Conditions: (i) HCl Conc. (1 Eq), H2O, Reflux 6 h.

Scheme 2. Reagents and Conditions: (i) 0.5 Eq of Piperidine, Reflux 7 h.

The triazino benzimidazole 1a and 2-guanidino benzimidazoles 2a–c, 2e, and 2f were previously obtained.33,34 Compounds 2a-c, 2e, and 2f(33) were reported as free base and/or salts and were characterized only by melting point and elemental analysis related to C and H. Herein, we report the structural elucidation in more detail, including 1H and 13C NMR.

Based on NMR spectra, cycloaddition of acetone to compounds 2 (2b, 2e, and 2f) did not show regioselectivity and gave the corresponding tricyclic compounds 1 as a 60/40 mixture of isomers I and II, respectively, namely, 1b-I and 1b-II, 1e-I, and 1e-II and 1f-I and 1f-II (Scheme 2).

The assignment of each specific isomeric peak and the definition of the proportions between the two isomers in the 1H NMR spectra, COSY, and NOESY experiments were consistent with the previous findings of Dolzhenko et al. relative to a structural analogue of series 1, namely, the 7(8)-methyl triazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole.34 The electronic nature of the R substituent in series 2 did not significantly influence the ring closure taking place at N-1 of benzimidazole and N-3 of the guanidino moiety; in fact, the isomer II, carrying the substituent at C(7) of the tricyclic scaffold always formed in a lower percentage than isomer I, that is substituted at C(8). The 3:2 ratio between the two isomers may be due to the steric hindrance exerted by the gem-dimethyl group of acetone during the formation of the dihydrotriazine ring, from which the R substituent of the guanidino benzimidazole preferentially arranges farther away.

In the 1H NMR spectrum, the C(6)–H signals of triazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole derivatives always display the highest chemical shift values among all the aromatic hydrogens as a result of the deshielding effect caused by their proximity to the gem-diCH3 groups.

The NMR spectra of the asymmetric disubstituted compound 1d allowed observation of the yield of only one reaction product. Dolzhenko and Chui previously described the formation of a cross-peak in the NOESY-2D spectra for the aromatic C(6)–H signal and the H atoms of the two gem-diCH3 groups at C(4).34 In our NOESY-2D and 1D experiments, a strong cross-peak for the doublet at 7.41 at C(6) and the singlet at 1.74 (gem-diCH3) appeared, confirming the exclusive formation of the 7,9-diCl isomer as 1d.

Since the attempt to separate the two isomers of 1f, such as representative samples of series 1, by HPLC (gradient elution with a binary solution—eluent A: H2O/HCOOH 0.1% v/v, eluent B: ACN/HCOOH 0.05% v/v) gave a negative result (see the HPLC chromatogram in SI), the 7(8)-monosubstituted triazino benzimidazoles 1b, 1e, and 1f were tested as a congeners’ mixture in biological and crystallographic experiments.

Regarding the 13C NMR spectra of 2-gauanidino benzimidazoles 2, the signals of carbons 3a, 7a, 4, and 7 are subject to extensive broadening and difficult to be attributed, as already depicted for 2a.35 This could be due to the prototropic interconversion among the 3 tautomeric forms and 14 isomers in which the 2-guanidino benzimidazole nucleus may exist;36 an analogous phenomenon was previously highlighted also for the 3 tautomeric forms of the triazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole scaffold.34

Structure–Activity Relationship Studies against Parasitic and Human Enzymes

The triazino benzimidazoles (1) and 2-guanidino benzimidazoles (2) were tested in enzymatic inhibition assays to investigate their activity profiles against TbPTR1 and TbDHFR (Table 2) seeking dual targeting anti-T. brucei agents. For comparison, the compounds' activities toward LmDHFR and TcDHFR were also evaluated. The kinetic inhibition experiments were conducted by determining the IC50 for each compound in appropriate experimental conditions suitable for deriving the corresponding Ki, assuming a competitive inhibition pattern, as reported in the Methods section. The competitive inhibition was supported by the X-ray crystal structures of the obtained protein/inhibitor complex in which the inhibitor was replacing the enzyme substrate. In the case of PTR1, the replaced substrate was DHB, while in DHFRs, the replaced substrate was DHF. Deepening the mechanistic aspects of the enzyme inhibition for all compounds was out of the scope of this work.

Table 2. Inhibition Constant (Ki) of Series (1) and (2) against TbPTR1 and DHFR Enzymesa.

| cmp | enzymatic screening | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TbPTR1 Ki (μM) | TbDHFR Ki (μM) | TbTS Ki (μM) | hDHFR Ki (μM) | hTS Ki (μM) | selectivity KiTbPTR1/KiTbDHFR | species selectivity KihDHFR/KiTbDHFR | species selectivity KihTS/KiTbTS | LmDHFR Ki (μM) | TcDHFR Ki (μM) | |

| 1a | 12.7 | 0.070 | 30.0 | 3.78 | >500 | 181 | 54 | >17 | 0.48 | 9.66 |

| 1b | 27.0 | 0.459 | 46.5 | 1.52 | >500 | 59 | 3.3 | >11 | 0.54 | 0.94 |

| 1c | 50.6 | 0.339 | 9.77 | 0.663 | >500 | 149 | 2.0 | >51 | 1.20 | 1.07 |

| 1d | 34.2 | 0.336 | 44.3 | 1.35 | >500 | 102 | 4.0 | >11 | 0.16 | 2.29 |

| 1e | 36.4 | 0.758 | 58.6 | 11.2 | >500 | 48 | 15 | >8.5 | 26 | 7.41 |

| 1f | 5.73 | 0.065 | 33.7 | 11.9 | >500 | 88 | 183 | >15 | 14.3 | 11.0 |

| 1g | 7.89 | 1.09 | 22.0 | 1.05 | >500 | 7.2 | 0.96 | >23 | 2.45 | 1.38 |

| 2a | 13.3 | 0.029 | 23.6 | 2.21 | >500 | 459 | 76 | >21 | - | - |

| 2b | 21.1 | 0.070 | 36.0 | 2.77 | >500 | 301 | 40 | >14 | 0.58 | 10.6 |

| 2c | 3.23 | 0.66 | 50.3 | 1.51 | >500 | 4.9 | 2.3 | >9.9 | 1.58 | - |

| 2d | 4.94 | 0.113 | 20.3 | 4.36 | >500 | 44 | 39 | >25 | - | - |

| 2e | 17.8 | 0.038 | 21.0 | 2.12 | >500 | 468 | 56 | >24 | - | - |

| 2f | 9.15 | 0.131 | 44.6 | 18.1 | >500 | 70 | 138 | >11 | - | - |

| 2g | 54.0 | 0.009 | 18.2 | 3.55 | >500 | 6000 | 394 | >27 | 1.04 | 0.60 |

| Cyc | 4.16 | 0.256 | - | 0.396 | 22.5 | 16 | 1.55 | - | - | - |

| Pyr | 0.016 | 0.038 | - | 0.247 | 11.8 | 0.4 | 6.50 | - | - | - |

| MTX | 0.138 | 0.006 | 46.3b | 0.004 | 1.57 | 23 | 0.67 | 0.03 | - | - |

Selectivity index for compounds 1 and 2 for Ki obtained against TbPTR1 vs TbDHFR, hDHFR vs TbDHFR, and hTS vs TbTS. Activity is compared with that of Cyc, Pyr, and MTX, as reference drugs. All the compounds demonstrated <10% inhibition activity when tested up to 200 μM against hTS.

Ki value from Gibson et al.17.

In general, the 2-guanidino benzimidazoles 2 resulted to be more potent than tricyclic derivatives 1, being able to steer their structural flexibility and the related binding ability to T. brucei enzymes. For both series, a preferential inhibition profile versus TbDHFR over TbPTR1 was observed, as demonstrated by the submicromolar/nanomolar potencies reached against TbDHFR that worsened from at least one up to 3 orders of magnitude against TbPTR1. Regarding the impact on the activity exerted by the chemical nature (polar or apolar) and electronic effect (electron-withdrawing or -donating) of the substituents considered, it can be observed that there is no correlation between the two series; indeed, a more prominent contribution to the inhibition activity against TbDHFR seems to be ruled by the steric effect of the substituent in combination with the bicyclic or tricyclic structure of the scaffold. Within the triazino benzimidazoles, the unsubstituted derivative 1a (Ki = 70 nM) and the 7(8)-OCH3 derivative 1f (Ki = 65 nM) were the most potent molecules, while among the open ring guanidino benzimidazoles the unsubstituted derivative 2a (Ki = 29 nM) and 5(6)-CF32e (Ki = 38 nM), all matching the nanomolar potency of Pyr toward TbDHFR (Ki = 38 nM). In addition, even better was the 5,6-dimethyl-2-guanidino benzimidazole 2g exhibiting a Ki of 9 nM against TbDHFR, which compared the potency of MTX (Ki = 6 nM). With respect to MTX, showing a selectivity index of 23 as the ratio between the Ki values of TbPTR1 and TbDHFR, compound 2g elicited interest for its very unbalanced inhibition profile, 6000-fold more favorable for TbDHFR (Table 2). In perspective, this highly selective and potent TbDHFR inhibitor is worthy of further investigations in drug combination tests with a potent and selective TbPTR1 inhibitor, conceivably with a view to getting better management of HAT.

Besides the inhibition of DHFR, also that of TS can interfere with the DNA replication leading to cell death.37 The activity of TS consists of the oxidation of N5,N10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate to DHF, and the methyl donor for the formation of dTMP from dUMP. These functions are unique to TS. Therefore, TS is notoriously recognized as a target for cancer therapy. Unlike mammals, protozoa cannot salvage thymidine and, thus, rely completely on the de novo thymidylate cycle by TS for the synthesis of dTMP.38 However, since the human and parasite TS enzymes share a strong similarity at the primary-sequence level, it is argued that compounds active against the parasite would also be toxic to the host. Hence, the compounds were tested for the inhibition of the TS domain of the bifunctional TbDHFR-TS. It is worth noting that all the Ki values for the compounds fall in the micromolar range as for the DHFR-targeting drugs Cyc, Pyr, and MTX (Table 2), markedly far from the nanomolar inhibition potency of the chemotherapy agent nolatrexed, which was designed to directly inhibit TS.17 To ascertain the species selectivity of the present compounds, i.e., the preference for the protozoan TbDHFR, the study of human DHFR (hDHFR) inhibition was also assessed. Both series showed micromolar inhibition constants against the hDHFR, except for the 7,8-dichloro triazino benzimidazole 1c, which reached a value of 663 nM, which was comparable to those of Cyc and Pyr, but higher than that of MTX (Ki = 4 nM). Hence, a valuable safety profile for these molecules was pointed out, as confirmed by the absence of cytotoxicity (CC50 > 100 μM, Table 3) against THP-1 cells. Indeed, the submicromolar activity of 1c against hDHFR matched up with the appearance of toxicity to the host (CC50 > 50 μM, Table 3). This observation was further corroborated by the calculation of the off-target activity on hTS. Indeed, all the compounds demonstrated <10% inhibition in kinetic assays when tested at 200 μM (Table 2).

Table 3. Antiparasitic Activities (EC50), Cytotoxicity (CC50), and Selectivity Index (SI)a,b.

| cmp | cell-based biological screening | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. brucei EC50 (μM) | T. brucei EC50 (μM) folate deficiency | THP-1 CC50 (μM) | SI CC50/EC50 | SI CC50/EC50 folate deficiency | L. infantum EC50 (μM) | |

| 1a | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 1b | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 1c | >20 | >20 | >50 | // | // | >20 |

| 1d | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 1e | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 1f | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 1g | 6.63 | 18.2 | >100 | 15.1 | 5.50 | >20 |

| 2a | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 2b | 15.2 | 15.2 | >100 | 6.58 | 6.60 | >20 |

| 2c | 7.8 | 6.52 | 95.3 | 12.2 | 14.6 | 22.5 |

| 2d | 2.91 | 5.97 | >100 | 34.4 | 16.8 | 6.62 |

| 2e | 18.2 | >20 | >100 | 5.50 | // | >20 |

| 2f | >20 | >20 | >100 | // | // | >20 |

| 2g | 14.5 | 13.8 | >100 | 6.91 | 7.2 | >20 |

| CYC | >80 | 27.2 | 221 | // | 8.12 | >80 |

| PYR | 17.3 | 2.08 | 105 | 6.07 | 50.4 | 99.2 |

| MTX | 23.3 | 0.0054 | - | // | // | - |

| PENT | 0.0041 | - | - | // | // | - |

| MLF | - | - | - | // | // | 10.9 |

Data are from three independent experiments and are expressed as mean; SD < 10%.

- represents not determined; // represents not detectable at the maximum compound solubility.

By the analysis of the species-selectivity profile (Table 2), as the ratio KihDHFR/KiTbDHFR, MTX turned out to be almost equipotent toward both orthologues (SI = 0.67), in agreement with its clinical application as an anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive agent. Analogous behavior was observed for Cyc (SI = 1.55), while Pyr manifested a ∼6.5-fold higher SI favoring the parasitic enzyme. The triazino benzimidazoles bearing a lipophilic substituent on the aromatic ring generally showed lower SI values ranging from 0.96 (1g) to 15 (1e), except for the unsubstituted derivative 1a (SI = 54) and the even more promising 7(8)-OCH3 analogue 1f (SI = 183), both endowed with a marked preference for TbDHFR. Apart from the 5,6-dichloro derivative 2c (SI = 2.3), the 2-guanidino benzimidazoles (series 2) performed better than Pyr, showing SI values up to the highest 394 for the 5,6-dimethyl derivative 2g, that confirmed to be the most potent and selective TbDHFR inhibitor. Intriguingly, as previously described for Cyc analogues depicted in Figure 1, the polar methoxy group confirmed its worthy impact on fostering the inhibition of the parasitic DHFR, thus allowing the yield of high values of selectivity for compounds 1f and 2f.

Concerning the other DHFRs from L. major and T. cruzi, the first enzyme seemed to be more sensitive as approximately 40% of the compounds tested showed submicromolar Ki values. The 7,9-diCl triazino benzimidazole (1d) and the unsubstituted analogue (1a) were found to be the most effective inhibitors of LmDHFR with Ki values equal to 0.16 and 0.48 μM, respectively. Differently, the 5,6-dimethyl guanidino benzimidazole 2g, the most active TbDHFR inhibitor, was proven to be also the best inhibitor of TcDHFR, but with a drop-off in potency of 67-fold (Ki = 0.60 μM). These encouraging data let envisage the validity of these chemotypes toward the development of broad-spectrum antiprotozoal agents.

The observed activity can be evaluated in a 3D structure obtained from the crystallization complexes of some of the best inhibitors with TbDHFR and TbPTR1 enzymes. In the next section, the structural analysis of the complexes is developed.

X-ray Crystallographic Structure of TbDHFR

At first, the X-ray crystal structure of the TbDHFR as apoenzyme was studied. Despite various attempts, we failed to crystallize the full-length TbDHFR-TS enzyme. On the other hand, we obtained crystals of the isolated TbDHFR domain, covering the N-terminal region extending to residue 241. The structure of TbDHFR was solved in complex with the cofactor NADP(H) and the inhibitor 1g to 2.90 Å resolution, showing an enzyme monomer in the crystal asymmetric unit (Tables S1 and S2). The model was fully rebuilt apart for starting twenty-two N-terminal and the last two C-terminal residues. The TbDHFR domain folds in 11 β-strands, eight α-helices, and one shorter 310 helix (Figure 3A), showing a structure remarkably similar to formerly reported models.26 The cofactor binds in an extended conformation, stabilized by a tight network of conserved interactions with the surrounding residues (Figure 3B). The adenine ring is enclosed in the pocket lined by Leu105 and Arg107 on the β4-α3 loop, Gly136 and Gly137 of loops β5-α5, and Gln168 on helix α7. The NADP(H) α-phosphate forms ionic bonds with Arg84 on helix α2 and is H-bonded to Ser106 of the β4-α3 loop, whereas the β and γ-phosphates entail H-bonds with Thr86 on helix α2 and the three starting residues of helix α7. The terminal ribose and nicotinamide moieties are accommodated in the pocket lined by Ala34 of strand β1, residues 41–47, belonging to strand β2 and the following loop β2-α1, Thr86, and Ser89 of helix α2, residues 160–161 of the β6-α7 loop, and Tyr166 on helix α7. Ala34 plays a key role in keeping the correct alignment of the cofactor nicotinamide inside the cavity; indeed, the NADP(H) amide moiety faces the peptide bonds of the residue, forming two H-bonds with it (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of TbDHFR (light green cartoon and carbons) in the ternary complex with the cofactor NADP(H) (in sticks, turquoise carbons) and 1g (in sticks, magenta carbons). (A) Overall fold of TbDHFR (α-helices and β-strands are colored yellow-green and dark green, respectively). (B) View of the cofactor biding site. (C) Active site view, showing binding of 1g; the inhibitor surrounded by the omit map (green mesh contoured at the 2.5σ level) is displayed in the inset. (D) Active site view of the superimposition between the complexes TbDHFR-NADP(H)-1g and TbDHFR-NADP(H)-Pyr (cofactor and Pyr in sticks, pink carbons; PDB id 3QFX).26 In all panels, oxygen atoms are colored red, nitrogen blue, sulfur yellow, and phosphorus magenta. H-bonds are shown as tan dashed lines.

Compound 1g Binding to the TbDHFR Catalytic Cavity

We selected compound 1g for crystallization purposes because it showed one of the most promising Ki values. The compound behaves as a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme with respect to the DHF substrate, and this is supported by the observed X-ray crystal structure of the complex TbDHFR:1g. The inhibitor occupies the dihydrofolate pocket, located over the nicotinamide ring of the cofactor (inhibitor estimated occupancy of 100%, Figure 3C). This pocket is mostly hydrophobic, except for the area above Ala34, being negatively charged through the exposure of the carboxylate moiety of Asp54, belonging to helix α1. The hydrophobic residues lining the catalytic cavity are Ala34 of strand β1, Ile47 on the β2-α1 loop, Met55 and Phe58 of helix α1, Leu90, Pro91, Phe94, and Leu97 on the loop α2-β4, and Ile160 of the β6-α7 loop (Figure 3C). Among these residues, Phe58 plays a key role in aligning the substrate inside the cavity and stacking with it through its aromatic ring. This interaction is also entailed by 1g, which exploits its benzimidazole rings to form π–π stacking with Phe58. The cofactor nicotinamide is located on the opposite side of the benzimidazole rings, to a distance of ∼3.5 Å. The aromatic systems of 1g and the cofactor form an angle of ∼80°, generating a distorted T-shaped interaction. Inside the cavity, 1g entails a network of van der Waals interactions with Ala34, Ile47, Met55, Thr86, and Leu90. The inhibitor is further stabilized by the H-bonds taken by its nitrogen N(3), which donates to Asp54, and by the C(2) amine moiety, which donates to both the Val33 backbone carbonyl and Thr185 hydroxyl groups (Figure 3C).

The comparison with the complex TbDHFR-NADP(H)-Pyr (PDB id 3QFX) shows both inhibitors occupying the same area of the active site (Figure 3D).26 The position of the 1g dihydrotriazine ring matches the Pyr pyrimidine moiety, sharing the interactions with Asp54 and Thr185. The cofactor nicotinamide is slightly shifted in the complex with Pyr, reasonably because of the hindrance generated by its p-Cl-phenyl moiety which is rotated by 90° on the pyrimidine plane (Figure 3D).

X-ray Crystallography of the Complexes of TbPTR1 with Inhibitors and the NADP(H) Cofactor

The structure of TbPTR1 was solved in complex with the cofactor NADP(H) and five inhibitors, 1f, 1g, 2c, 2d, and 2f (Tables S1 and S2); the overall structure of TbPTR1 is described in the SI. The tricyclic compounds 1f and 1g were crystallized with TbPTR1 and their structures were determined to 1.70 and 1.71 Å resolution, respectively (Tables S1 and S2). In the complex with 1g, the inhibitor binds inside all four catalytic cavities of the TbPTR1 tetramer, although to a low extent in subunit B (estimated to 50%; inhibitor and cofactor estimated occupancies are summarized in Table S3). On the other hand, three chains of the enzyme tetramer are populated in the complex with 1f, whereas in the fourth, only the cofactor is observed (Table S3). The PTR1 substrate, DHB, is replaced by the compounds; therefore, these structural bases support a competitive inhibition pattern with respect to DHB.

In both complexes, the tricyclic inhibitors occupy the substrate-binding pocket, being stacked in the peculiar NADP(H) nicotinamide-Phe97 π-sandwich (Figure 4A,B). The compounds are also stabilized inside the pocket by a tight network of conserved H-bonds entailed with the cofactor and surrounding residues. The nitrogen N(1) of the dihydrotriazine ring receives a H-bond from the NADP(H) ribose hydroxyl, whereas the nitrogen N(3) donates a H-bond to the cofactor β-phosphate. The amine moiety in position 2 of the same ring donates a first H-bond to the same cofactor phosphate, and a second is entailed with the Ser95 hydroxyl. A further H-bond is formed with the Tyr174 hydroxyl, which donates a H-bond to the benzimidazole nitrogen N(10). The inhibitors are characterized by peculiar substituents on the terminal benzene ring, being two methyl groups in positions 7 and 8 of 1g (Figure 4A) and a 7-methoxy group in 1f (Figure 4B). The methyl group in position 8 of 1g is directed toward the Trp221 indole, forming van der Waals interaction with it (Figure 4A). The substituents in position 7 of both inhibitors are accommodated inside the hydrophobic region lined by Val206, Leu209, Pro210, Met213, and Trp221 (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Active site view of TbPTR1 (light cyan car A–E): Active site view of TbPTR1 (light cyan cartoon and carbons) in the ternary complex with the cofactor NADP(H) (in sticks, turquoise carbons) and (A) 1g (in sticks, magenta carbons), (B) 1f (in sticks, light yellow carbons), (C) 2f (in sticks, green carbons), (D) 2d (in sticks, orange carbons), and (E) 2c (in sticks, purple carbons). The inhibitor surrounded by the omit map (green mesh contoured at the 2.5σ level) is displayed in the inset of each panel. (F) Structural comparison among the binding modes of compounds 1g (in sticks, magenta carbons), 1f (in sticks, light yellow carbons), 2f (in sticks, green carbons), 2d (in sticks, orange carbons), and 2c (in sticks, purple carbons) within the TbPTR1 active site (light cyan cartoon and carbons). The comparison highlights the slight opening of Phe97 in the complexes with the tricyclic compounds 1g and 1f (in yellow). This rotation is required to accommodate the bulkier substituents on their dihydrotriazine rings, distorting the peculiar π-sandwich with the cofactor nicotinamide. On the other hand, in the complexes with 2c, 2d, and 2f, Phe97 (in purple) is parallel to the guanidino benzimidazole moiety of the inhibitors and the NADP(H) nicotinamide. In all panels, oxygen atoms are colored red, nitrogen blue, sulfur yellow and phosphorus magenta. Water molecules are shown as red spheres (arbitrary radius) and H-bonds as tan dashed lines.

Three additional bicyclic compounds, 2c, 2d, and 2f, were crystallized in complex with TbPTR1 and the structures were determined to medium-high resolution (1.86, 1.49, and 1.70 Å, respectively; Tables S1 and S2). In the three complexes, the inhibitor populates the active site of all enzyme subunits within the TbPTR1 tetramer (Table S3), showing conserved binding modes and interactions inside the catalytic cavities (Figure 4C–E). The shared guanidino benzimidazole moiety of the compounds occupies the biopterin binding pocket, positioning the five-membered ring inside the NADP(H) nicotinamide-Phe97 π-sandwich. The benzimidazole nitrogen N(1) donates a hydrogen bond to the Tyr174 hydroxyl. Furthermore, the guanidinium moiety in position 2 donates four H-bonds to Ser95 and the NADP(H) β-phosphate and ribose hydroxyl (Figure 4C–E). These interactions are shared with the tricyclic inhibitors 1g and 1f, having the terminal dihydrotriazine ring that mimics the binding mode of the guanidium moiety (Figure 4A,B). Compounds 2c, 2d, and 2f differ in the substituents on the terminal benzene ring. A 5-methoxy is present in compound 2f (Figure 4C), whereas the inhibitors 2c and 2d have two chlorines in positions 5,6 and 4,6, respectively (Figure 4D,E). The substituent in position 5, either the chlorine in 2c or the methoxy in 2f, is accommodated inside the hydrophobic pocket lined by Val206, Leu209, Pro210, Met213, and Trp221 (Figure 4C,E). The shared 6-chlorine of 2c and 2d is directed toward the nearby area defined by Asp161, Met163, Cys168, and Trp221 (Figure 4D,E). In the complex with 2d, water-mediated interactions are formed between this chlorine and both the Asp161 carboxylate and the Gly205 back carbonyl (Figure 4D). On the other hand, the second chlorine substituent in position 4 of 2d faces Leu209 and Pro210, belonging to the substrate-binding loop.

The comparison among the complexes highlights that all compounds populate the active site with analogous binding modes, forming shared interactions with Ser97, Tyr174, and the cofactor. The variable portions of the inhibitors mainly entail hydrophobic interactions inside the cavity resulting in similar Ki values (ranging from 3.23 to 9.15 μM). The cavity configuration is tightly conserved upon inhibitor binding, except for a slight opening of Phe97 in the complexes with tricyclic compounds 1f and 1g (Figure 4F). Indeed, the phenyl ring of Phe97 is rotated by ∼30°, accommodating the bulky dimethyl substituents on the dihydrotriazine rings of 1f and 1g, and distorting the peculiar π-sandwich with the cofactor nicotinamide.

The binding mode of the compounds was compared to those formerly described for Cyc (PDB id 6HNC) (Figure 5A) and Pyr (PDB id 7OPJ) (Figure 5B).25,27 Cyc shares with the tricyclic compounds 1f and 1g the terminal dihydrotriazine ring, acting as an anchoring moiety inside the substrate-binding pocket (Figure 5A). The binding mode of this moiety inside the cavity is remarkably similar, forming also conserved interactions with the cofactor and Ser95. An additional amine substituent is present on the dihydrotriazine ring of Cyc, mimicking the same interaction with Tyr174 formed by the benzimidazole nitrogen N(10) of tricyclic compounds 1g and 1f. A more planar geometry characterizes the terminal guanidinium group of bicyclic compounds 2c, 2d, and 2f, better mimicking the planar triazine ring of Pyr (Figure 5B). The comparison among their complexes enlightens that they share the same interactions inside the substrate-binding pocket, involving the cofactor, Ser95, and Tyr174. On the opposite side of the cavity, Pyr and Cyc form a peculiar halogen bond with Trp221, through the p-chlorine on their phenyl moiety (Figure 5A,B). Despite the presence of either 5,6-diCl or 4,6-diCl substituents on the 2c and 2d benzimidazole rings, the inhibitors are not correctly aligned with Trp221, preventing the formation of the same type of interaction.

Figure 5.

Active site view of the superimposition between the structure of TbPTR1 (light cyan cartoon and carbons) in complex with NADP(H) (in sticks, turquoise carbons) and (A) 1g (in sticks, magenta carbons) and Cyc (in sticks, gold carbons; PDB id 6HNC(25)); (B) 2c (in sticks, purple carbons) and Pyr (in sticks, pink carbons; PDB id 7OPJ(27)); (C) 1g (in sticks, magenta carbons) and the tricyclic inhibitor PI (1, in sticks, gray carbons; PDB id 6TBX(21)); (D) 2c (in sticks, purple carbons) and the tricyclic inhibitor PI (1, in sticks, gray carbons; PDB id 6TBX(21)). In all panels, oxygen atoms are colored red, nitrogen blue, sulfur yellow, and phosphorus magenta.

We formerly reported the development of a tricyclic-based inhibitor, named compound PI (PDB id 6TBX(21)) (Figure 1 and 5C,D). The comparison with the binding modes of tricyclic (1g in Figure 5C) and bicyclic compounds (2c in Figure 5C,D) shows conserved orientations, highlighting once again the importance of the interactions entailed with the cofactor, Ser95, and Tyr174, acting as the main anchoring points inside the cavity (Figure 5C,D).

In Vitro Antiparasitic Activity

The compounds were initially benchmarked for their cytotoxicity against the monocytic THP-1 cell line of human leukemia (Table 3). Excepting the 7,8-dichloro-2-aminotriazino benzimidazole 1c, which produced certain toxicity (CC50 > 50 μM), all the compounds showed a high margin of safety (CC50 = 95.3 to >100 μM). Hence, they were evaluated for their in vitro antiparasitic activities against the cultured bloodstream form of T. brucei and promastigote stage of L. infantum, to probe their potential broad-spectrum antitrypanosomatidic activity.

The compounds were tested at 20 μM against T. brucei and L. infantum, and only when the cell growth inhibition was higher than 50%, a dose response experiment was performed to calculate the corresponding EC50 values (Table 3). Cyc, Pyr, and MTX were used as antifolate reference drugs; pendamidine (PENT) and miltefosine (MLF) were the positive controls for antitrypanosoma and antileishmanial activity tests, respectively (Table 3).

In the case of T. brucei, the activity was evaluated using two media: complete HMI-9 medium, corresponding to a final folate concentration of 9 μM; folate deficiency HMI-9 medium, corresponding to a final folate concentration of about 20 nM, aimed at evaluating the effect of folic acid on the inhibition potency of the compounds. The competitive inhibition mechanism of the molecules was investigated by adding DHF, as a natural substrate of TbDHFR.

The parasite most sensitive to the action of the compounds resulted in T. brucei whose growth was affected by 71% of 2-guanidino benzimidazoles (series 2) which provided EC50 values in the range from 2.91 (2d) to 18.2 μM (2e). The active compounds were monosubstituted at position 5 (2b, 2e), disubstituted at positions 5 and 6 (2c, 2g), or 4 and 6 (2d) of the benzimidazole ring with lipophilic groups, both electron-withdrawing (Cl, CF3) or electron-donating (CH3). Conversely, the presence of a polar group (5-OCH3, 2f) rather than the absence of substituents (2a) was associated with the loss of activity (EC50 > 20 μM).

In the series of triazino benzimidazoles 1, only the 7,8-dimethyl derivative (1g) was proven to inhibit T. brucei, reaching an EC50 of 6.63 μM. Collectively, in the standard folate medium, the compounds showed an antiparasitic activity improved or comparable to those of antifolate drugs Pyr and MTX (EC50 of 17.3 and 23.3 μM, respectively), even better than that of Cyc (EC50 > 80 μM).

In relation to the screening carried out in the folate deficiency medium, the compounds showed no gain in the activity trend, which remained unvaried with respect to folate standard conditions. This supports the concept that these compounds may have a multitargeting activity and do not inhibit only the folate-dependent enzymes, such as DHFR or PTR1.

Differently, for the antifolate reference drugs, the activity ameliorated in the folate deficiency medium, as markedly evidenced by MTX whose EC50 enhanced 4300-fold passing from 23.3 μM to 5.4 nM. Such a behavior agreed with previous findings, in which antifolate drugs containing a terminal glutamic acid moiety like MTX and pemetrexed demonstrated the highest potency against T. brucei when tested in a medium deficient in folate and/or thymidine. This polar side chain was proposed to be relevant for transport and subsequent increased retention of these folate mimetic inhibitors in the trypanosome after polyglutamylation, a post-translational modification leading to an improved antiparasitic effect. The same did not happen to folate inhibitors Pyr, trimetrexate, and nolatrexed where potency did not change between medium types likely due to the fact that they are more lipophilic and lack the terminal glutamyl moiety.17 Analogous consideration could be made for the present compounds, for which lipophilicity was predicted through the SwissADME Web site calculating their Log P values39 in comparison to MTX, pemetrexed, Cyc, Pyr, trimetrexate, and nolatrexed. Interestingly, the results, listed in Table S4, confirmed for both series Log P values were always higher than those of MTX, and pemetrexed (except for 2a and 2f), and comparable to those of the other antifolate drugs.

Finally, most of the compounds did not show an appreciable antiparasitic activity against the promastigote form of L. infantum (Table 3) apart from the 2-guanidino derivatives 2d (EC50 = 6.62 μM) and 2c (EC50 = 22.5 μM), surpassing the potency of Cyc (EC50 > 80 μM) and Pyr (EC50 = 99.2 μM) and well matching that of MLF, which exhibited an EC50 of 10.9 μM. Thus, they demonstrated a valuable broad-spectrum antiparasitic activity, by affecting both Trypanosoma and Leishmania parasites' growth.

Conclusions

To bring out new opportunities for the treatment of HAT and Leishmaniasis, we uncovered two novel chemotypes starting from the structural analysis of Cyc and Pyr, which were proven to be attractive template molecules targeting the DHFR and PTR1 of T. brucei. Accordingly, the amino dihydrotriazine moiety of Cyc was condensed to the benzimidazole nucleus giving the 2-aminotriazino benzimidazoles of series 1, which demonstrated a nanomolar inhibition of TbDHFR and 2 orders of magnitude lower activity against TbPTR1. The isosteric replacement of the 2-aminotriazine moiety from series 1 delivered the 2-guanidino group in series 2, as less conformationally constrained analogues, which even improved their performance against TbDHFR reaching the low nanomolar potency range. Outstandingly, the 5,6-dimethyl-2-guanidinobenzimidazole 2g was found to be the most potent (Ki = 9 nM) and highly selective TbDHFR inhibitor, 6000-fold over TbPTR1 and 394-fold over hDHFR. Considering its peculiar selectivity for TbDHFR, 2g could be valorized in drug combination tests with a potent and selective TbPTR1 inhibitor to yield the synergistic inhibition of the trypanosomatid folate pathway.

However, the pronounced potency against TbDHFR of 2g and structural analogues (2b–2e) is not reflected against the whole cells, as the antiparasitic activity ranges in the low micromolar domain and does not vary linearly with enzymatic inhibition potency. This also encompasses the 7,8-dimethyl triazino benzimidazole (1g), the only compound of series 1 to be found as active against T. brucei parasites (EC50 = 6.63 μM). Conceivably, this outcome could be attributed to the modest inhibition of TbPTR1, whereby the compounds do not properly achieve the dual inhibition of both folate enzymes. Although the definition of a single inhibitor motif targeting both enzymes remains elusive, the structural elucidation of TbDHFR and TbPTR1 in complex with the present chemotypes may benefit the design of more promising, or even dual, inhibitors. Since only few cocrystal structures have been released for TbDHFR, the TbDHFR:1g complex presented in this study may significantly expand on the knowledge of the bonding interactions mapping for active site inhibition, which can serve the purpose of supporting future design work and provide suggestions for the tailored modification of TbDHFR inhibitors.

The strongly basic dihydrotriazine scaffold of Cyc was previously demonstrated to mainly exist in the protonated form at physiological pH. The Cyc protonated form can be held liable for its poor bioavailability. To overcome this issue, in malaria therapy, Cyc is administered through its better-suited prodrug, proguanil. Conceivably, a similar consideration could be made for the present compounds, incorporating the dihydrotriazine ring of Cyc or an isostere guanidine thereof. Thus, subsequent studies deserve to investigate the pharmacokinetic profile of both series that could have jeopardized them from achieving their intracellular targets. For instance, modification of their pKa’s leading to a less alkaline character should be taken into account to improve their subcellular uptake and distribution, thus reaching lower EC50 in vitro. Moreover, the discovery of the 2-guanidino benzimidazoles 2d and 2c as potent and broad-spectrum antiprotozoan leads by inhibiting Trypanosoma and Leishmania parasites may offer the prominent opportunity to affect multiple parasitic diseases, which needs to be further explored.

Methods

Chemistry

Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Zentek (Milan, Italy). Melting points were determined using a Büchi apparatus and are uncorrected. 1H NMR spectra and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using a Jeol instrument at 400 and 101 MHz, respectively; chemical shifts are reported as δ (ppm) and are referenced to DMSO-d6, quintet at 2.5 ppm (1H), septet at 39.5 ppm (13C); J in Hz. Elemental analyses were performed on a Flash 2000 CHNS (Thermo Scientific) instrument in the Microanalysis Laboratory of the Department of Pharmacy, University of Genova. NMR spectra of the novel compounds are shown in the Supporting Information. Results of elemental analyses indicated that the purity of all compounds was ≥95%.

Synthesis of 2-Aminotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazoles 1a–g

A mixture of the proper 2-guanidinobenzimidazole of series 2 (5.7 mmol) and piperidine (2.9 mmol) dissolved in 5 mL of acetone was heated at 70 °C for 7 h. The reaction mixture was then concentrated under vacuum and kept cooling to r.t. overnight. The expected product precipitated as a white solid, which was filtered and crystallized from acetone/Et2O.

2-Amino-4,4-dimethyl-3,4-dihydrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1a)

Yield: 59%. M.p. 284.8–285.6 °C (M.p. 295–296 °C34). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.71 (s, 1H, NH), 7.35 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.24 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.98 (td, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H, C(7)–H arom.), 6.91 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H, C(8)-H arom.), 6.36 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.77 (s, 6H, C(4)-diCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 155.21, 153.66, 143.74, 130.67, 120.55, 118.90, 116.08, 109.60, 69.31, 28.50 (2C). Anal. calcd for C11H13N5: C 61.38, H 6.09, N 32.54; found: C 61.31, H 6.12, N 32.30.

2-Amino-7(8)-chloro-4,4-dimethyl-3,4-diidrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1b)

Yield: 41%, m.p. 161.2–163 °C. Ratio 1b-I/1b-II: 60% 1b-I and 40% 1b-II. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1b-I δ 7.68 (s, 1H, NH), 7.35 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.23 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.89 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H, C(7)–H arom.), 6.36 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.74 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3). 1b-II δ 7.65 (s, 1H, NH), 7.40 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.20 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.99 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H, C(8)–H arom.), 6.33 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.75 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1b-I δ 155.48, 155.08, 145.27, 129.59, 124.97, 118.32, 115.37, 110.43, 69.79, 28.34 (2C); 1b-II δ 155.36, 154.56, 142.76, 131.43, 122.94, 120.57, 116.86, 109.30, 69.44, 28.30 (2C). Anal. calcd for C11H12N5Cl: C 52.91, H 4.84, N 28.05; found: C 52.89, H 5.16, N 28.09.

2-Amino-7,8-dichloro-4,4-dimethyl-3,4-dihydrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1c)

Yield: 56%. M.p. 285.1–285.9 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.73 (s, 1H, NH), 7.59 (s, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.40 (s, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.43 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.75 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 155.75, 155.62, 144.11, 130.42, 122.90, 120.39, 116.52, 110.52, 69.58, 28.17 (2C). Anal. calcd for C11H11N5Cl2: C 46.50, H 3.90, N 24.65; found: C 46.43, H 4.00, N 24.30.

2-Amino-7,9-dichloro-4,4-dimethyl-3,4-dihydrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1d)

Yield: 89%, m.p. 283.2–283.7 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.86 (s, 1H, NH), 7.41 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.11 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, C(8)–H arom.), 6.46 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.74 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3).13C (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 155.64, 155.10, 139.97, 132.07, 122.73, 120.11, 119.97, 108.39, 69.74, 28.21 (2C). Anal. calcd for C11H11N5Cl2: C 46.50, H 3.90, N 24,65; found: C 46.68, H 3.71, N 24,71.

2-Amino-7(8)-trifluoromethyl-4,4-dimethyl-3,4-dihydrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1e)

Yield: 20%, m.p. 259–261 °C. Ratio 1e-I/1e-II: 60% 1e-I and 40% 1e-II. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1e-I δ 7.78 (s, 1H, NH), 7.53 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.50 (s, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 7.20 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H, C(7)–H arom.), 6.43 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.79 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3); 1e-II δ 7.80 (s, 1H, NH), 7.57 (s, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.36 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 7.30 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H, C(8)–H arom.), 6.47 (s, 2H, NH2), 1.79 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3). 13C (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1e-I δ 155.77, 155.58, 143.82, 133.28, 125.31 (d, 1JCF = 272.7 Hz), 121.42 (q, 2JCF = 31.2 Hz), 115.47 (d, 3JCF = 3.8 Hz), 112.41 (d, 3JCF = 3.7 Hz), 109.71, 69.59, 28.38 (2C); 1e-II δ 156.18, 155.50, 147.03, 130.36, 125.44 (d, 1JCF = 272.7 Hz, CF3), 118.92 (q, 2JCF = 31.5 Hz), 117.77 (d, 3JCF = 3.6 Hz), 115.91, 106.10 (d, 3JCF = 3.7 Hz), 69.64, 28.32 (2C). Anal. calcd for C12H12F3N5: C 50.88, H 4.74, N 24.72; found: C 50.82, H 4.53, N 24.75.

2-Amino-7(8)-methoxy-4,4-dimethyl-3,4-dihydrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1f)

Yield: 21%. M.p. 264–266 °C. Ratio 1f-I/1f-II: 64% 1f-I and 36% 1f-II. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1f-I δ 7.63 (s, 1H, NH), 7.21 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 6.82 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.52 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.5 Hz, 1H, C(7)–H arom.), 6.27 (s, 2H, NH2), 3,72 (s, 3H, C(8)–OCH3), 1.72 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3); 1f-II δ 7.59 (s, 1H, NH), 7.13 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.88 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 6.63 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H, C(8)–H arom.), 6.22 (s, 2H, NH2), 3,75 (s, 3H, C(7)–OCH3), 1.75 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1f-I δ 155.14, 154.70, 153.48, 144.86, 125.16, 109.58, 106.42, 100.77, 69.21, 55.32, 28.43 (2C); 1f-II δ 154.81, 154.38, 153.07, 137.97, 131.09, 116.15, 107.56, 95.90, 69.24, 55.72, 28.43 (2C). Anal. calcd for C12H15N5O: C 58.76, H 6.16, N 28.55; found: C 59.03, H 6.22, N 28.93.

2-Amino-4,4,7,8-tetramethyl-3,4-dihydrotriazino[1,2-a]benzimidazole (1g)

Yield: 40%. M.p. 266.5–268.5 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.54 (s, 1H, NH), 7.12 (s, 1H, C(6)–H arom.), 7.02 (s, 1H, C(9)–H arom.), 6.16 (s, 1H, NH2), 2.25 (s, 3H, C(8)–CH3), 2.21 (s, 3H, C(7)–CH3), 1.73 (s, 6H, C(4)–diCH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 154.91, 153.07, 142.09, 129.06, 128.09, 126.73, 116.89, 110.33, 69.14, 28.49 (2C), 19.90, 19.75. Anal. calcd for C13H17N5: C 64.17, H 7.04, N 28.78; found: C 64.22, H 7.32, N 28.50.

Synthesis of 2-Guanidino Benzimidazoles 2a–g

The properly substituted 1,2-phenylendiamine (1,4 mmol) and dicyandiamide (1,4 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL of H2O, and 0.23 mL (1,4 mmol) of conc. HCl. The mixture was heated to reflux for 6h with stirring. After cooling to rt, the solution was alkalinized with 6 M NaOH inducing the precipitation of an amorphous solid, which was either crystallized from Et2O (2a) or purified by CC (SiO2/Et2O + 10% MeOH) (2b–2g), to afford the final product. Compounds 2b, 2c, and 2e were converted to their respective hydrochloride salts by adding HCl 1N (ethanolic solution) to perform elemental analysis.

2-Guanidinobenzimidazole (2a)

Yield: 59%. M.p. 237–240 °C (m.p. 243–244 °C33). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.95 (br s, 1H, benzimidazole exchangeable NH), 7.33–6.46 (br s, 4H, 2NH, and NH2 signals superimposed to H arom.), 7.18–7.12 (m, 2H, H arom.), 6.93–6.88 (m, 2H, H arom.), 3.35 (br s, 1H, NH signal partially superimposed to the H2O peak). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 158.96, 158.72, 133.60 (2C), 119.36 (2C), 111.91 (2C). Anal. calcd for C8H9N5: C 54.85, H 5.18, N 39.98; found: C 54.51, H 5.40, N 39.94.

5(6)-Chloro-2-guanidinobenzimidazole (2b)

Yield: 40%. M.p. 208–211 °C (M.p. 207 °C33). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.12 (br s, 1H, benzimidazole exchangeable NH), 7.20–6.50 (br s, 3H, NH and NH2 signals superimposed to H arom.), 7.15 (s, 1H, H arom.), 7.11 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 6.90 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 3.38 (br s, 1H, NH signal partially superimposed to the H2O peak). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 160.16, 158.99, 142.76, 133.63, 123.54, 119.06, 113.84, 109.77. Anal. calcd for C8H8ClN5 · 2HCl: C 34.01, H 3.57, N 24.79; found: C 34.06, H 3.45, N 24.88.

5,6-Dichloro-2-guanidinobenzimidazole (2c)

Yield: 70%. M.p. 236–240 °C (M.p. 244 °C33). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.21 (s, 1H, benzimidazole exchangeable NH), 7.29 (s, 2H, H arom.), 6.97 (br s, 3H, NH + NH2), 3.34 (br s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 161.01, 159.20, 121.09 (2C), 114.13 (2C), 110.33 (2C). Anal. calcd for C8H7Cl2N5·HCl: C 34.25, H 2.87, N 24.96; found: C 34.31, H 3.10, N 24.54.

4,6-Dichloro-2-guanidinobenzimidazole (2d)

Yield: 40%. M.p. 244–245.5 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.60 (s, 1H, benzimidazole exchangeable NH), 7.17 (br s, 3H, NH + NH2), 7.12 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 7.05 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, H arom.). 3.34 (br s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 159.29, 158.88, 135.72, 131.13, 123.42, 119.00, 115.24, 109.11. Anal. calcd for C8H7Cl2N5: C 39.37, H 2.89, N 28.69; found: C 39.44, H 3.02, N 28.38.

5(6)-Trifluoromethyl-2-guanidinobenzimidazole (2e)

Yield 38%. M.p. 200–203 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.38 (br s, 4H, 2NH + NH2), 7.72 (s, 1H, H arom.), 7.59 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 7.49 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H, H arom.). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 156.46, 149.15, 137.33, 134.68, 124.88 (q, 1JCF = 271.5 Hz), 122.61 (q, 2JCF = 31.5 Hz), 118.96 (d, 3JCF = 3.9 Hz), 113.70, 110.54. Anal. calcd for C9H8F3N5·HCl: C 38.65, H 3.24, N 25.04; found: C 38.41, H 3.21, N 25.01.

5(6)-Methoxy-2-guanidinobenzimidazole (2f)

Yield: 36%. M.p. 201.7–202.7 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.88 (br s, 1H, benzimidazole exchangeable NH), 7.20–6.26 (br s, 3H, NH and NH2 signals superimposed to H arom.), 7.03 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 6.74 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 6.53 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H, H arom.), 3.71 (s, 3H, C(5)–OCH3), 3.34 (br s, 1H, NH signal partially superimposed to the H2O peak). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 158.84, 158.44, 154.02, 133.97, 111.54, 107.05, 96.72, 55.35. Anal. calcd for C9H11N5O: C 52.67, H 5.40, N 34.13; found: C 52.63, H 5.45, N 34.43.

5,6-Dimethyl-2-guanidinobenzimidazole (2g)

Yield: 65%. M.p. 167.2–170 °C (m.p. 191 °C33). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.84 (s, 1H, benzimidazole exchangeable NH), 6.94 (s, 2H, H arom.), 6.84 (br s, 3H, NH + NH2 signals partially superimposed to H arom.), 3.35 (br s, 1H, NH), 2.22 (s, 6H, C(5)–CH3 and C(6)–CH3). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 158.98, 158.57, 135.81 (2C), 127.57 (2C), 112.97 (2C), 20.39 (2C). Anal. calcd for C10H13N5: C 59.10, H 6.45, N 34.46; found: C 59.16, H 6.74, N 34.73.

HPLC Chromatography

The product was analyzed using an Agilent 1100 HPLC-MSD Ion Trap XCT system equipped with an electrospray ion source (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Chromatographic analyses were performed using a Waters Symmetry 300 C18 column (particle size 3,5 μm–150 × 1 mm) at room temperature and gradient elution with a binary solution (eluent A: H2O/HCOOH 0.1% v/v, eluent B: ACN/HCOOH 0.05% v/v). The analysis started with 0 of B (t0); then, B was increased to 100% (from t0 to t1 = 30 min), then kept at 100% (from t1 to t2 = 35 min), and finally returned to 0% of eluent B in 7 min. The flow rate was 300 μL/min and the injection volume was 8 μL. UV detection was monitored at 254. Mass spectra were acquired in positive ion mode, in the 50–500 m/z range and ion charged control with a target ion value of 50,000 and an accumulation time of 300 ms. A capillary voltage of 3000 V, nebulizer pressure of 10 psi, drying gas of 5 L/min, dry temperature of 325 °C, and rolling averages of 3 (averages: 5) were the parameters set for the MS detection.

Protein Production for X-ray Crystallography and Enzymatic Characterization

Recombinant TbDHFR-TS and TbDHFR

6xHis-TbDHFR-TS (EC:1.5.1.3) was produced in E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) cells and purified by exploiting the N-terminal His6-tag, according to established protocols.40

The synthetic gene encoding for TbDHFR, optimized for E. coli expression, and cloned in the pET-15b expression vector within the NdeI-BamHI restriction sites (pET15b–TbDHFR plasmid), was purchased from GenScript. Through this plasmid vector, the target protein is produced as a thrombin cleavable His6-tag protein (HT-TbDHFR), allowing its purification through the IMAC technique. The pET15b–TbDHFR plasmid was used to heath-shock transform chemically competent E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) cells. Bacteria were cultured at 20 °C in the ZYP-5052 autoinduction medium41 (supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin) for 48 h under vigorous aeration (220 rpm). Cells, harvested by centrifugation (3500 g, 15 min, 8 °C), were resuspended in buffer A (25 mM KPi pH 7.4 and 0.15 M NaCl), supplemented with lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL) and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and disrupted by sonication after 30–60 min of incubation on ice. The supernatant of the resulting crude extract, including the target protein, was clarified by centrifugation (14,000g, 1 h, 8 °C). HT-TbDHFR was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography on a HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE-Healthcare), performing the elution from the matrix using buffer A supplemented with 250–500 mM imidazole. Collected fractions including the target protein, identified by SDS-PAGE analysis, were combined and subjected to dialysis in buffer A at 8 °C (dialysis membrane cutoff 14 kDa). The His6-tag was cleaved during dialysis by adding thrombin protease (5U/mgHT-TbDHFR) to the target sample. The resulting mature TbDHFR was separated by a second stage of nickel-affinity chromatography and finally purified through size-exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75pg (GE-Healthcare), equilibrated in buffer A. The high purity of the final sample of mature TbDHFR was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis (purity >98%) and high-resolution MS (aa 244, M.W. 26,549.71 Da), and the yield was established to be ∼9 mg/Lcell culture. Enzymatic activity of each protein was calculated with kinetics direct assay and spectrophotometric readout as reported in the literature.27,40 Measured parameters for TbDHFR-TS for the reductase domain were kcat 1.07 ± 0.06 s–1, KM(DHF) 4.88 ± 1.15 μM, and KM(NADPH) 23.01 ± 5.12 μM.27,40

Recombinant LmDHFR-TS

Recombinant LmDHFR-TS (EC:1.5.1.3) was cloned in the pET-15b(TEV) vector and expressed in theE. coli strain ArcticExpress (DE3). Bacterial culture was grown at 30 °C in ZYP-5052 autoinduction medium (supplemented with ampicillin 100 mg/L) to OD600 nm value of about 1, and then cell growth was continued for 60 h at 12 °C under vigorous aeration. Cells, harvested by centrifugation (3500g, 15 min, 8 °C), were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM sodium citrate pH 5.5 and 0.25 M NaCl), supplemented with lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL) and 0.1 mM PMSF, and disrupted by sonication after 30–60 min of incubation on ice. The enzyme was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography on a HisTrap FF 5 mL column (GE-Healthcare), performing the elution from the matrix using buffer A, supplemented with 250–500 mM imidazole. Collected fractions including the target proteins, identified by SDS-PAGE analysis, were combined and dialyzed overnight in buffer A at 8 °C. The resulting protein sample was further purified on a gel filtration column (HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200pg, GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer A. The high purity of the final sample was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (≥98%) and MS (aa 541, M.W. 61,094.19 Da), and the yield was established to be ∼20 mg/Lcell. Enzymatic activity of each protein was calculated with kinetics direct assay and spectrophotometric readout as reported in the literature.27,40 Enzymatic measured parameters for LmDHFR were kcat 13.02 ± 1.12 s–1, KM(DHF) 4.56 ± 0.98 μM, and KM(NADPH) 11.1 ± 1.25 μM. These data agree with previous literature studies.27,42,43

Recombinant TcDHFR-TS

The synthetic gene encoding for TcDHFR-TS, optimized for E. coli expression and cloned in the pET-11a expression vector, was purchased from GenScript. The plasmid vector was introduced by thermal shock in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3). The bacterial culture was grown at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin. Protein over-expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG when the cell density reached an OD600 nm of 0.6–0.8 and cell growth was continued at 25 °C for 16 h. Cells, harvested by centrifugation (3500 g, 15 min, 8 °C), were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2), supplemented with lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL) and 0.1 mM PMSF, and disrupted by sonication. The enzyme was purifed by anion exchange chromatography (Mono Q HR 16/10 column, 20 mL) and proteins were eluted using a linear gradient of sodium chloride (0-500 mM). Fractions containing TcDHFR-TS were identified by SDS-PAGE, pooled and concentrated. The resulting sample was purified by size-exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200pg column (GE-Healthcare), equilibrated with 25 mM Tris pH 7.2, 250 mM NaCl, and 10 mM DTT. The target protein was further purified through a second anion-exchange DEAE Sepharose FF column (GE-Healthcare), using a linear gradient of sodium chloride (0–250 mM) in 25 mM Tris pH 7.2, supplemented with 10 mM DTT. The high purity of the final sample of mature proteins was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (≥98%) and MS (aa 521, M.W. 58,853.26 Da, per monomer), and the yield was established to be ∼15 mg/Lcell. Enzymatic activity was calculated with kinetics direct assay and spectrophotometric readout as reported in the literature.27,40 Measured parameters for TcDHFR-TS were kcat 28.01 ± 2.22 s–1, KM(DHF) 2.35 ± 0.24 μM, and KM(NADPH) 8.12 ± 0.84 μM, which agree with previous findings.43

Recombinant TbPTR1

6xHis-TbPTR1 (EC:1.5.1.33) was produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and purified by exploiting the N-terminal His6-tag (HT-TbPTR1), according to established protocols.40 The synthetic gene encoding for TbPTR1 is cloned in the pET-15b vector. The pET15b–TbPTR1 plasmid was used to heath-shock transform chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Bacteria were cultured at 30 °C in Luria–Bertani broth supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin under vigorous aeration (220 rpm) and induced with 1 mM IPTG at 30 °C overnight. Cells, harvested by centrifugation (3500 g, 15 min, 8 °C), were resuspended in 50 mM Tris HCl, 250 NaCl, pH 7.5, supplemented with lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL) and 0.1 mM PMSF, and disrupted by sonication after 30–60 min of incubation on ice. The supernatant of the resulting crude extract, including the target protein, was clarified by centrifugation (14,000g, 1 h, 8 °C). HT-TbPTR1 was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography on a HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE-Healthcare), performing the elution from the matrix using buffer A supplemented with 250–500 mM imidazole. Collected fractions including the target protein, identified by SDS-PAGE analysis, were combined and subjected to dialysis in buffer A at 8 °C (dialysis membrane cutoff 14 kDa). The high purity of the final sample of HT-TbPTR1 was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis and high-resolution MS (aa 289, 30,764.99 Da, per monomer), and the yield was established to be ∼9 mg/Lcell culture. Enzymatic activity was calculated with kinetics direct assay and spectrophotometric readout as reported in the literature.27,40 Kinetic parameters for TbPTR1 were kcat 0.74 ± 0.07 s–1, KM(BH2 or DHB) 5.62 ± 0.64 μM, and KM(NADPH) 12.30 ± 0.31 μM.40

Recombinant hDHFR

6xHis-hDHFR (EC:1.5.1.3) was produced in E. coli strain ArcticExpress(DE3) cells. The synthetic gene encoding for hDHFR, optimized for E. coli expression and cloned in the pET15b expression vector within the NdeI-BamHI restriction sites, was purchased from GenScript. Through this plasmid vector, the target protein is produced as a thrombin cleavable His6-tag protein. The pET15b–hDHFR plasmid was used to heath-shock transform chemically competent E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) cells. Bacterial culture was grown at 30 °C in ZYP-5052 autoinduction medium (supplemented with ampicillin 100 mg/L) to OD600 nm value of about 1, and then cell growth was continued for 60 h at 12 °C under vigorous aeration. Cells, harvested by centrifugation (3500g, 15 min, 8 °C), were resuspended in buffer A (25 mM KH2PO4 pH 7 and 50 mM NaCl), supplemented with lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL) and 0.1 mM PMSF and disrupted by sonication after 30–60 min of incubation on ice. HT-hDHFR was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography on a HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE-Healthcare). The target protein was eluted using buffer A supplemented with 250 mM imidazole. Collected fractions containing HT-hDHFR were combined with thrombin protease (3 units/mgHT-hDHFR) and dialyzed overnight in buffer A (membrane cutoff 14 kDa) at 8 °C. The resulting mature hDHFR was separated by a second stage of nickel-affinity chromatography and finally purified through size-exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75pg (GE-Healthcare), equilibrated in buffer A. The high purity of the final sample of mature hDHFR was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (≥98%) and high-resolution MS (aa 190, M.W. 21,734.00 Da), and the yield was established to be ∼10 mg/Lcell culture. Enzymatic activity was calculated with kinetics direct assay and spectrophotometric readout as reported in the literature.27,40 Human enzymes for the measurement of the compounds' off target activity were characterized as well, and hDHFR exhibited a kcat of 1.21 ± 0.14, KM(DHF) 5.41 ± 0.84 μM, and KM(NADPH) 9.98 ± 1.14 μM. These data agree with previous studies.44

Recombinant hTS

6xHis-hTS (EC:2.1.1.45) was produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and purified by exploiting the N-terminal His6-tag, according to established protocols.40 The synthetic gene encoding for hTS, optimized for E. coli expression, was cloned in the pQE80L expression vector within the BamHI-HindIII restriction sites (pQE80L–hTS plasmid). Through this plasmid vector, the target protein is produced as His6-tag protein allowing its purification through the IMAC technique. The pQE80L–hTS plasmid was used to heath-shock transform chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Bacteria were cultured at 30 °C in LB medium (supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin) under vigorous aeration (220 rpm) to OD600 nm value of 0.6–0.8, and then 0.1 mM IPTG was added for 4hs at 37 °C. Cells, harvested by centrifugation (3500g, 15 min, 8 °C), were in buffer A (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 30 mM NaCl) supplemented with lysozyme (0.5 mg/mL) and 0.1 mM PMSF and disrupted by sonication after 30–60 min of incubation on ice. HT-hTS was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography on a HisTrap FF 5 mL column (GE-Healthcare), performing the elution from the matrix using buffer A supplemented with 250–500 mM imidazole. Collected fractions including the target protein, identified by SDS-PAGE analysis, were combined and subjected to Hi trap size exclusion to remove imidazole. The high purity of the final sample of HT-hTS was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis as >98% and high-resolution MS (aa 325, M.W. 37,114 Da, per monomer), and the yield was established to ∼20 mg/Lcell culture. Human enzymes for the measurement of the compounds' off target activity were characterized as well, and hTS kcat is 0.98 ± 0.03 s–1, KM(dUMP) 13.44 ± 1.21 μM, and KM(THF) 5.87 ± 0.98 μM. These data agree with the literature.45

Protein Crystallization

TbPTR1 was crystallized at room temperature by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion technique, as described elsewhere.46 Briefly, well-ordered TbPTR1 crystals grew within a few days (to final dimensions of ∼600 μm × 400 μm × 100 μm) in drops prepared by mixing equal volumes of protein (20–40 mg/mL, in 20 mM TRIS, pH 7.5 and 10 mM DTT) and precipitant (1.6–2.5 M sodium acetate and 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5) solutions. TbPTR1–NADP(H)–inhibitor complexes were obtained by the soaking technique; compound solutions (in DMSO) were added to a final concentration of 4–5 mM directly to the drops containing preformed protein crystals. After 1–2 h exposure, crystals were washed in the cryoprotectant solution (30% v/v glycerol, 2 M sodium acetate, and 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

The purified sample of TbDHFR (6 mg/mL, in buffer A) was cocrystallized with the cofactor NADPH (2 mM) and the inhibitor 1g (4 mM), using the microbatch method at room temperature. Crystallization drops were prepared by mixing equal volumes (1.5 μL) of the ternary complex solution and the precipitant, 35% (w/v) PEG4000, 50 mM ammonium sulfate, 50 mM bis–tris, pH 6.5, under Al’s oil. Needle-shaped crystals, grown within a few days, were transferred to the cryoprotect (precipitant supplemented with 25% v/v PEG400) and then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The cocrystallization of TbDHFR (6 mg/mL, in buffer A) in complex with the cofactor NADPH (2 mM) and the inhibitor 2g (2–4 mM) was also attempted using both the microbatch method and the vapor diffusion technique, at room temperature. Crystallization trials were performed in both methods using precipitant solutions including different concentrations of PEGs (10–40% (w/v) of either PEG3350, PEG4600, or PEG8000) and ammonium sulfate (10–200 mM), in 50 mM bis-tris, pH 6.0–7.0. Small needle-shaped crystals were obtained using the microbatch under the oil (Al’s oil) technique, which showed only poor diffraction when tested using synchrotron radiation.

X-ray Crystallography

Diffraction data were collected using synchrotron radiation at Diamond Light Source (DLS, Didcot, United Kingdom) beamlines I04 and I24, equipped with the Dectris Eiger2 XE 16 M detector and a Pilatus3 6 M detector, respectively, and at European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, France) beamline ID23-1, equipped with Eiger X 9M. X-ray diffraction data were integrated using XDS47 and scaled with Aimless48,49 from the CCP4 suite.50TbPTR1 crystals belong to the monoclinic space group P21, with only slight variations in the cell parameters among crystals. Four enzyme chains, forming a functional TbPTR1 tetramer, populate the crystal asymmetric unit (ASU). TbDHFR crystals belong to the orthorhombic space group P212121 with one protein monomer in the crystal ASU. Data collection and processing statistics are reported in Table S1. The structures were solved by molecular replacement using the software Molrep.51 For TbPTR1 structures, a whole enzyme tetramer (PDB id 6TBX(21)) was used as the search model; on the other hand, a single monomer (PDB id 3QFX(26)) was adopted as the model for TbDHFR. All structures were refined with the program REFMAC552 from the CCP4 suite. The molecular graphic software Coot53 was used for electron density inspection and model manipulation. Since early cycles of refinement, large positive maxima were observed in both cofactor and substrate sites, having shapes and sizes coherent with their population by NADP(H) and inhibitor molecules. Exogenous ligands were modeled in these sites according to the visible electron densities, and their occupancies were adjusted and refined to values resulting in atomic-displacement parameters close to those of the neighboring protein atoms in fully occupied sites. The automatic placement of water molecules was performed in all structures with the ARPwARP suite.54 The final models were inspected manually and checked with the programs Coot and Procheck;55 refinement and validation statistics are summarized in Table S2. Coordinates and structure factors were validated and deposited in the PDB, under accession codes 8RHT (TbDHFR–NADP(H)–1g (P25)), 8RHU (TbPTR1–NADP(H)–1g (P25)), 8RHV (TbPTR1–NADP(H)–1f (P30)), 8RHW (TbPTR1–NADP(H)–2f (P31)), 8RHX (TbPTR1–NADP(H)–2d (P32)), and 8RHY (TbPTR1–NADP(H)–2c (P34)). Figures were generated with CCP4 mg.56

Enzyme Inhibition Assays

Compounds to be tested were dissolved in DMSO at 100 μM stock solution and 1:10 dilutions. DMSO final concentration in the sample was <4% vol/vol in order to not interfere with the reaction rate during inhibition assays.

TbPTR1 Inhibition Assay

A direct kinetic assay was performed to monitor NADPH consumption over time with a Jasco V730 double-beam spectrophotometer. Thawed protein was incubated in 40 mM citrate buffer pH 3.7 at a final concentration of 30 nM and with the endogenous substrate dihydrobiopterin at a final concentration of 27 μM, in a Kartell semimicro disposable polystyrene plastic cuvette (Kartell LABWARE, Milan, Italy). The inhibitor was added at increasing final concentration from the DMSO initial stocks and incubated with the enzyme for 15 min at room temperature. Every compound was assayed in duplicate and in parallel with the noninhibited protein control assay. NADP(H) solution at a final concentration of 134 μM was then added to the cuvette to start the reaction, and the Δ(OD)/min at 340 nm was recorded over 180s at 25 °C and DHB of 27 μM.27 Six different concentrations were measured and plotted with a 3PL fitting. A 95% interval of confidence (CI) of fitting was employed to calculate the associated standard error per each curve fitting, and a t-student was run per each duplicate with a p-value ≤ 0.05. GraphPad Prism Suite (2021) was employed for data fitting and statistics. Associated Ki for each inhibitor was calculated from IC50 assuming a competitive, nontight binding inhibition mode, according to the kinetic assumption that IC50 = Ki(1 + [S]/[Km]).57 Pyrimethamine (Ki = 0.016 μM), cycloguanil (Ki = 4.16 μM), and methotrexate (Ki = 0.138 μM) were used as reference inhibitors.

TbDHFR-TS Inhibition Assay versus the DHFR Domain