Dear Editor,

In September 2022, a 22-year-old Malawian female presented with acute jaundice after consuming twice the prescribed dosage of medications while undergoing family-administered directly observed treatment for pulmonary TB. The patient was a participant in the CLO-FAST study, a phase 2c randomized trial1 to evaluate early bacteriologic efficacy, safety and tolerability of an ultrashort 3-month experimental regimen of once-daily rifapentine (P, RPT; 1,200 mg daily), isoniazid (H, INH; 300 mg daily), pyrazinamide (Z, PZA; 1,000 mg daily), ethambutol (E, EMB; 800 mg daily), and clofazimine (C, CFZ; 100 mg daily, administered with a 2-week 300 mg daily loading dose). The participant received standard-of-care treatment (rifampin [RIF]/INH/PZA/EMB at standard weight-based dosing) for 5 days prior to initiating the study medications; she was taking no other medication associated with hyperbilirubinemia or known to interact with RPT. The patient was randomized to the experimental PHZEC regimen and the prescribed doses (Figure); however, on study Day 2, the patient erroneously took two full doses of the regimen 5 h apart (at 08:00 and 13:00 hours). That evening, the treatment supporter reported that the participant had developed jaundice. The participant was advised to discontinue the study medications on Day 3, but not before the patient had already taken another dose of the study regimen and underwent an urgent clinical evaluation. At baseline, the patient weighed 33 kg and had a body mass index of 14.47 kg/m2. At the screening visit, total bilirubin was 0.2 mg/dL (normal range, 0.2–1.2 mg/dL), with a direct fraction of 0.07 mg/dL; ALT was 7 IU/L (normal range, 0–33 IU/L), AST was 9 IU/L (normal range, 13–37 IU/L), and alkaline phosphatase was 144 IU/L (normal range, 24–118 IU/L). Serologic testing for hepatitis A and B was negative; anti-hepatitis C antibody was initially positive but was undetectable on re-testing 9 months later. HIV type 1 and 2 antigens and antibodies were negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen was unremarkable, and the patient reported no history of alcohol use. Following the resolution of jaundice and normalization of bilirubin levels, the experimental PHZEC regimen was resumed on Day 11. The patient subsequently completed the study regimen with no further episodes of jaundice (Figure), and liver enzymes and biochemical tests remained within normal limits.

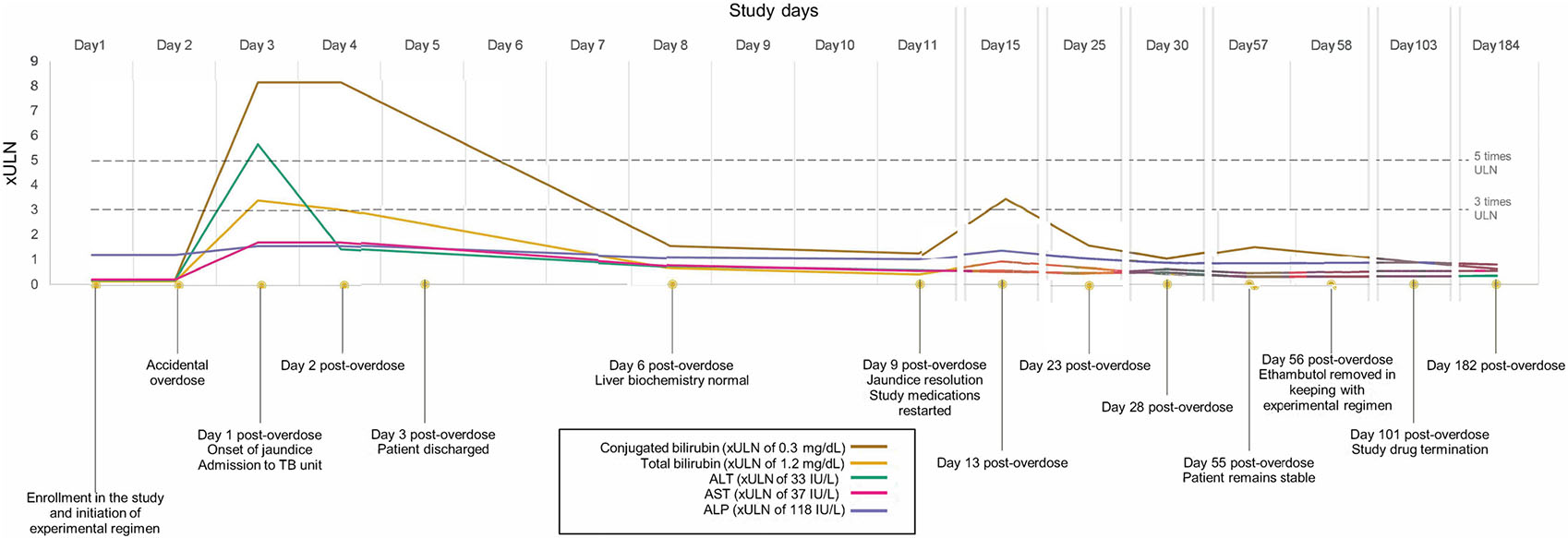

Figure.

Timeline of events. The accidental overdose of study medications occurred on Day 2 (two doses of study treatments), followed by a rapid rise primarily in conjugated bilirubin and subsequent quick resolution in liver biochemistry levels: total bilirubin (peak, 4.1 mg/dL), conjugated bilirubin (peak: 2.45 mg/dL), ALT (peak: 187 IU/L), AST (peak: 64 IU/L), and ALP (peak: 187 IU/L) are shown as multiples of their respective ULN range. ALT = alanine transaminase; AST = aspartate transaminase; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; IU = international units.

RPT, a synthetic derivative of RIF, was developed in 1965, and the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved its use for pulmonary TB since 1998. Access to RPT remains limited outside the United States,2,3 and published evidence on programmatic experience is limited. When established on treatment following an auto-induction phase, RPT has a longer terminal half-life (15 h, compared to 2 h for RIF) and higher potency against Mycobacterium tuberculosis relative to RIF, but decreasing (rather than increasing) bioavailability with increased dose.4 There is substantial interindividual variability in RPT pharmacokinetics.5 The 521T → (rs4149056) polymorphism in SLCO1B1, the gene that encodes hepatocyte organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B (OATP1B1), will presumably predict slower clearance of RPT, as it does with statins.4 The rs1803155 G→A variant in AADAC, which encodes an enzyme that deacetylates RPT, has been associated with decreased RPT clearance.6 Genotyping of a stored specimen from this participant showed AADAC rs1803155 GG, predicting rapid RPT clearance (~6% of black Africans are GG); SLCO1B1 rs4149056 TT predicting normal transporter activity (~96% of Black Africans); NAT2 slow acetylator genotype, predicting higher INH exposure (~50% of Black Africans); and UGT1A1 rs887829 TT predicting slower conjugation of bilirubin (Gilbert’s trait; ~25% of Black Africans). UGT1A1 genotype likely contributed to this participant’s elevated unconjugated bilirubin, but not to the elevated conjugated bilirubin. Acute and transient conjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurs in a dose-dependent manner with RIF,7 and although unstudied, RPT is expected to behave similarly. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurs due to inhibition by RIF of the hepatic transporter OATP1B. Bilirubin is an endogenous substrate for the OATP1B transporter, as are coproporphyrins, bile acids, and dicarboxylate. In the HIGHRIF1 early bactericidal activity study,8 participants received RIF at doses ranging from 20 to 50 mg/kg for 14 days. For doses up to 40 mg/kg, dose-dependent acute conjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurred early (typically, within the first few days) and waned quickly, presumably due to an adaptive increase in the number of OATP1B transporters or reduced RIF concentrations by auto-induction.9

Our study participant consumed 2,400 mg (66.7 mg/kg) of RPT within 5 h, a dose not examined in prior clinical studies.10-12 A phase 1 clinical trial administering RPT doses up to 1,800 mg/day (median 1,350 mg/day) was stopped early for poor tolerability.10 Tuberculosis Trials Consortium (TBTC) Study 29,11 a phase 2 RPT dose-ranging trial, did not investigate RPT doses above 20 mg/kg with a highest administered dose of 1,500 mg daily. The phase 3 TBTC Study 31/A534912 reported a significantly larger proportion of participants with grade 3 or higher serum total bilirubin levels within the 4-month RPT-based regimen containing moxifloxacin (3.3% vs. 1% in the control arm), although adverse events of hepatocellular drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with jaundice were few and distributed equally.12 Classic anti-TB medication-induced DILI (TB-DILI) is considered a clinical diagnosis of exclusion, with a typical latent period of weeks to months. The strongest confirmation of the diagnosis is often based on rechallenge with the suspected drug causing a greater than two-fold ALT elevation, and discontinuation leading to a fall in ALT.13 Our report in the context of the literature summarized above suggests that RPT-associated conjugated hyperbilirubinemia can be clinically differentiated from TB-DILI by 1) RPT doses above 20 mg/kg, 2) a predominant rise in conjugated bilirubin out of proportion to liver enzyme elevation, and 3) rapid resolution of conjugated bilirubin upon initial withholding of RPT, followed by continuation at conventional doses. Accordingly, these factors suggest RPT-associated conjugated hyperbilirubinemia over classic TB-DILI in the current case, despite double doses of PZA and INH in the context of the patient’s slow acetylator status. Finally, the entity is clinically distinct from RPT hypersensitivity syndrome, which is characterized by anaphylactoid signs and symptoms with few hepatotoxic manifestations and is surprisingly common among healthy volunteers receiving high-dose RPT.10

With efforts to expand availability and use of high-dose RPT for drug-susceptible TB and TB infection,14,15 and newer patient-centered dosing formulations that exceed 150 mg/pill on the horizon, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia may become more commonly observed if liver function is maintained. For our patient, malnutrition may have increased her risk of DILI, and we cannot rule out the possibility that the companion regimen contributed to hepatic toxicity. Clinicians prescribing high-dose RPT should be aware of the possibility of RPT-associated conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and its resolution with conservative management (i.e., temporary suspension followed by reintroduction without the need for individual drug rechallenge).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants who volunteered for the ACTG Study A5362. Genotyping was performed at Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE). The research reported here was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Award nos. UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636, and UM1 AI106701). This work was supported in part by grants funded by the National Center for Research (grants R01 AI077505, UM1 AI069439, UL1 TR002243, the Malawi site core grant (2005794197), and the Malawi site ACTG grant (1560 B LC935). This study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health Advancing Clinical Therapeutics Globally for HIV/AIDS and Other Infections (ACTG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: JM, DH, ES, KS, IW, and GM have institutional funding from NIH. JM is also chair of the NIH ACTG Trial A5362. ES has institutional funding from UNITE4TB, a Veni Grant from the Dutch Research Council (The Hague, Utrecht, The Netherlands), and a UNITAID grant. ES has research collaborations with TB Alliance (New York, NY, USA) and Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Beerse, Belgium). ES is a DSMB member for the BE-PEOPLE Study and a member of the CHEETA Task Force. The remaining authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Metcalfe J. Clofazimine- and rifapentine-containing treatment shortening regimens in drug-susceptible tuberculosis: The CLO-FAST Study. ClinicalTrials.gov, 2020. NCT04311502. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04311502 Accessed December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guglielmetti L, et al. Rifapentine access in Europe: growing concerns over key tuberculosis treatment component. Eur Respir J 2022;59(5):2200388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frick M. An activist’s guide to rifapentine for the treatment of TB infection. Treatment Action Group, 2020. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/publication/an-activists-guide-to-rifapentine-for-the-treatment-of-tb-infection/ Accessed January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung JY, et al. Effect of OATP1B1 (SLCO1B1) variant alleles on the pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78(4):342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savic RM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of rifapentine and desacetyl rifapentine in healthy volunteers: Nonlinearities in clearance and bioavailability. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58(6):3035–3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis J, et al. A population pharmacokinetic analysis shows that arylacetamide deacetylase (AADAC) gene polymorphism and HIV infection affect the exposure of rifapentine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019;63(4):e01964–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori D, et al. Dose-dependent inhibition of OATP1B by rifampicin in healthy volunteers: comprehensive evaluation of candidate biomarkers and OATP1B probe drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020;107(4):1004–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Te Brake LHM, et al. Increased bactericidal activity but dose-limiting intolerability at 50 mg·kg–1 rifampicin. Eur Respir J 2021;58(1):2000955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svensson RJ, et al. A population pharmacokinetic model incorporating saturable pharmacokinetics and autoinduction for high rifampicin doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018;103(4): 674–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dooley KE, et al. Novel dosing strategies increase exposures of the potent antituberculosis drug rifapentine but are poorly tolerated in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59(6):3399–3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorman SE, et al. Daily rifapentine for treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: A randomized, dose-ranging trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191(3):333–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorman SE, et al. Four-month rifapentine regimens with or without moxifloxacin for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2021;384(18):1705–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saukkonen JJ, et al. An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174(8):935–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment Drug-susceptible tuberculosis treatment. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr W, et al. Interim guidance: 4-month rifapentine-moxifloxacin regimen for the treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis–United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71(8):285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]