Abstract

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are considered as the novel treatment modality in certain cancers. They may soon be used widely even as the first-line option for cancer treatment due to their remarkable efficacies and impacts on survival rates, particularly in cases of advanced metastatic cancer. Of note, these agents might unveil new autoimmune diseases as well as causing flare-ups of a pre-existing autoimmune disease. Data in this field have been accumulated during recent years. Early detection and a collaborative approach are, therefore, crucial in the management of a patient who presents with any of these conditions. Herein, we report a patient with a diagnosis of metastatic renal cell cancer presented with vasculitis involvement in the aorta during nivolumab treatment. Our aim with this case is to increase the awareness of ICI-related vasculitis involvement among rheumatologists in the light of literature.

Keywords: Cancer treatment, Immune checkpoint inhibition, Aortitis

Introduction

Since the therapeutic role of T cells in the treatment of cancer has been well established, the significance of regulatory molecules, such as currently available antibodies targeting either the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) or the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), and medications targeting these pathways, known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has exponentially increased in standard oncology practice [1]. This paradigm shift in cancer treatment has provided long-term survival in some advanced metastatic malignancies. Besides our understanding of their efficacy with their widespread use in the last decade, data regarding adverse events associated with ICIs have been increasingly identified in the last few years [2]. Indeed, oncologists are the most familiar clinicians in monitoring and managing these patients. However, from some aspects mentioned above, rheumatologists should be aware of the potential impacts of ICIs that may trigger and/or exacerbate autoimmune diseases via unknown mechanisms [3]. In the literature, polymyalgia rheumatica and rheumatoid-arthritis-like syndromes are most commonly reported clinical entities in patients received ICIs, whereas sicca syndrome, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, and systemic sclerosis have also been described as case reports [4]. Vasculitis involvement can vary, but it most frequently occurs in relation to large vessels, such as the aorta and its branches. Here, we report a case of nivolumab-related vasculitis that affected the aorta and its branches.

Case presentation

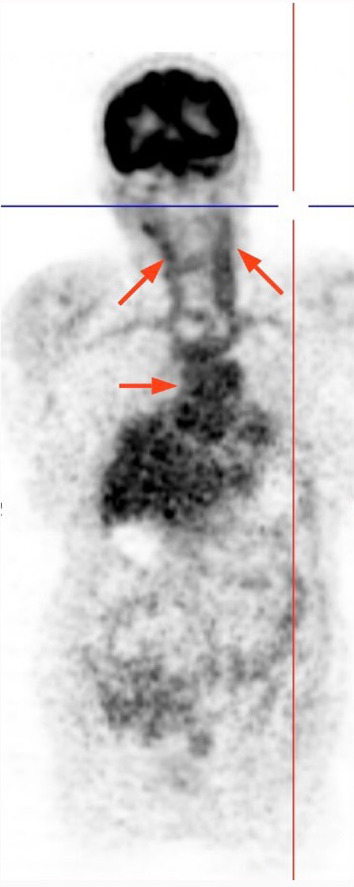

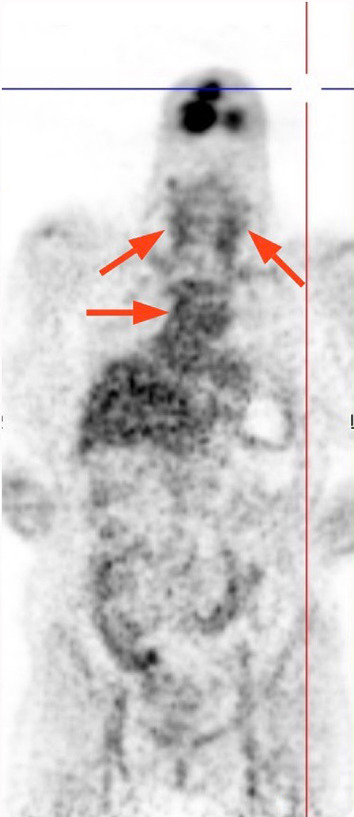

A 69-year-old female with a diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) for 3 years was consulted due to increased metabolic activity in the bilateral carotid arteries, and thoraco-abdominal aorta, consistent with vasculitis involvement on PET–CT scan at last oncology visit (Fig. 1). Previous radiologic exams did not reveal anything concerning the aorta and its branches or evidence of a cancer that was still active but was thought to be in remission after receiving nivolumab. The patient's medical history showed that a metastatic (brain) RCC diagnosis was made in 2019. She was initially given cranial radiotherapy and sunitinib after a left-sided nephrectomy for three months, but nivolumab was later given as a result of a tumor recurrence at the primary site. She received a two-week radiotherapy treatment because of a metastatic lesion at the L5 vertebrae. Based on the radiologic assessment, the patient was then regarded as being in remission. Totally, she was given 58 cycles of nivolumab (240 mg every 2 weeks). At the admission to our rheumatology clinic, the systemic rheumatologic questionnaire was unremarkable with no complaints of headache, fever, jaw claudication, morning stiffness, tenderness at temporal regions. She did not report any loss of appetite, bone pain, and weight loss except non-specific complaints such as fatigue, myalgia, back pain. Physical examination was unrevealing with normal vital signs and bilateral radial and femoral pulse, and no evidence of pathologic murmur on chest auscultation. Laboratory investigations were significant for increased C-reactive protein (CRP) (46 mg/l) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (89 mm/h). Bilateral Doppler ultrasound imaging of temporal arteries was normal, and serum anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody titers (ANCA) were also negative. No evidence of active malignancy was found clinically and radiologically (her last PET–CT scan was normal). After ruling out all other possibilities, we consider nivolumab as an initiating factor based on literature data, despite a weak temporal association between the initiation of nivolumab and the development of vasculitis. As a result, nivolumab was stopped following a collaborative agreement with oncology because the patient had been free of any signs of an active cancer for more than 6 months. Control PET–CT imaging revealed ongoing vasculitis in the aorta and its branches after three months of watchful approach (Fig. 2). Additionally, serum acute phase parameters were relatively higher (CRP of 118 mg/dl and ESR of 62) than the previous visit. Of note, no symptoms suggestive of malignancy were also reported. Thus, the patient was placed on moderate dose methylprednisolone (32 mg/day) with a tapering regime. Despite persistently elevated CRP and ESR levels 4 months following steroid treatment, PET-CT imaging showed no vasculitis involvement in the aorta and its branches (Fig. 3). At the last visit (6 months after steroid initiation), acute phase parameters were within normal reference values with 2 mg daily methylprednisolone. Two months later, the patient was lost due to sudden cardiac death at home.

Fig. 1.

PET–CT scan showed increased activity in bilateral carotid arteries and thoraco-abdominal aorta at admission

Fig. 2.

In the third month, activity relatively decreased but was still ongoing

Fig. 3.

No activity suggestive of vasculitis in the aorta and its branches was found in PET–CT imaging at month 7 of follow-up

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are novel therapeutic agents with encouraging results in certain metastatic malignancies such as melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma [1]. Ipilimumab and nivolumab are the most preferred agents, showing efficacy by targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors, respectively [1]. Despite their outstanding benefits, it is important to note that ICIs may trigger immune-related adverse events. In routine practice, endocrine (thyroid dysfunction), gastrointestinal (mucositis) and cutaneous (dermatitis) are the most frequently affected organ systems, but the spectrum can be variable from mild to life-threatening involvement [1]. According to retrospective observational studies, rheumatoid-like arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and myalgias are most reported ICI-related rheumatic manifestations. However, vasculitis, albeit relatively uncommon, can also occur in the form of large vessel vasculitis (LVV) especially giant cell arteritis (GCA), aortitis and vasculitis of the central nervous system [3, 5, 6]. Additionally, it has been shown that ICI use may also exacerbate the pre-existing rheumatic disease in nearly more than half of cases, therefore rheumatologists should be cognizant of these potential ICI-associated rheumatic adverse events [7].

When a patient develops vasculitis while receiving ICIs or later, it is important to consider the possibility of paraneoplastic vasculitis (PV), a condition marked by vasculitis involvement secondary to primary tumor via unknown mechanisms. This can be observed in the presence of an active malignancy or as a sign of recurrence; therefore, extensive malignancy investigation is mandatory in all cases [8]. Distinguishing between ICI-related vasculitis and PV is of utmost importance as they have different management and outcomes. Despite challenges in differential diagnosis, duration of vasculitis development, type of underlying malignancy (hematologic over solid in PV) and less responsive to steroids might make the diagnostic dilemma in favor of PV [8]. After excluding recurrence of malignancy with clinical and radiologic examinations, it was unlikely to consider this possibility in our case.

Based on the study reported by Daxini et al. [5], ICI-related vasculitis typically emerged within a median of 3 months following drug administration (1–6 months). In the literature, we have found six reported cases of ICI-related aortitis so far (characteristics, management and outcomes of patients are summarized in Table 1) [9–14]. In our review, it appears that ICI-related aortitis may occur several months after initiation of the drug (maximum 33 months) and most (5 out of 7 cases) received nivolumab treatment. Treatment generally is based on cessation of the culprit agent and/or administration of steroids with achievable remission in many cases [5–9, 14]. We initially preferred a watchful approach with cessation of nivolumab. However, ongoing inflammation seen on subsequent imaging with concomitant high acute phase has led to addition of steroids. Interestingly, inflammation in the aorta and its branches improved following steroid therapy, but the acute phase remained persistently elevated, without any reasonable explanations. There is no consensus in managing these patients as data regarding this adverse event are scarce in the literature. Watchful approach as well as steroids and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can be given according to the severity of ICI-related adverse events. Thus, treatment should be tailored individually in collaboration with oncologists.

Table 1.

Characteristics, management and outcome of immune checkpoint inhibitors related aortitis cases in the literature including our case

| Study | Cancer type | Age (years) | Sex | Involved area | Vessel type | Immunotherapy | Targeted molecule | Time from ICIs to vasculitis onset (mo) | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our case | Renal cell cancer | 68 | F | Aorta and its branches | LVV | Nivolumab | PD-1 | 33 | Discontinued nivolumab steroid 3 months later | Vasculitis improved at 6 months, the patient was lost due to SCD |

| Roy et al. [9] | Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung | 57 | M | Periaortitis | LVV | Nivolumab | PD-1 | 9 | Discontinued nivolumab. Methylprednisolone 60 mg IV once then oral prednisone tapered over 4 weeks | ND |

| Loricera et al. [10] | Melanoma | 48 | F | İsolated aortitis | LVV | Nivolumab | PD-1 | 2 | ND | ND |

| Hotta et al. [11] | Non-small cell lung cancer | 66 | M | Periaortitis | LVV | Nivolumab | PD-1 | 24 | Discontinued nivolumab | Remission |

| Henderson et al. [12] | Metastatic prostate cancer | 67 | M | Aorta and its branches | LVV | İpilimumab and nivolumab | PD-1, CTLA-4 | ND | IV pulse MP and 60 mg prednisolone | Remission |

| Ban et al. [13] | Melanoma | 51 | F | İsolated aortitis | LVV | İpilimumab | CTLA-4 | 2 | Prednisone 1 mg/kg daily for 3 weeks | Remission |

| Pinkston et al. [14] | Melanoma | ND | ND | ND | LVV | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | 1 | ND | ND |

M male, F female, ND not defined, LVV large vessel vasculitis, SCD sudden cardiac death, IV intravenous, MP methylprednisolone, ICIs immune checkpoint inhibitors

Nivolumab is a monoclonal antibody that primarily targets PD-1 molecules, particularly used effectively in refractory cases of lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma. Although increased T cell activity is the main proposed mechanism theoretically, the pathogenesis beyond occurrence of vasculitis in the setting of ICIs have not been elucidated yet. Zhang et al. [15] published a study conducting transcriptomic analysis of histopathologic specimens of giant cell arteries (GCA) in 68 patients for investigating the role of PD-1 and PDL-1 receptors and signals in inflammation. They have found that PDL-1 expression is low in GCA, with a selective defect in the specific dendritic cells (DCs) expressing PDL-1 in these arteries. In contrast, the presence of PD-1 receptor in affected sera is notable and most T cells in the vasculitis region expressed PD-1 receptor. Interestingly, it was also observed that inhibition of PD-1/PDL-1 interaction augments T cell accumulation in the vessel wall which later causes profound inflammation [15, 16]. These findings with the recent clinical observations might explain the background pathogenesis of LVV occurrence following ICI treatment. This specific type of involvement, particularly large vessels, might potentiate for novel therapeutic implications in LVV in the future.

Conclusion

Post-marketing rheumatic adverse events of ICIs, including aortitis, have been increasingly described during recent years. Rheumatologists will undoubtedly encounter these events more frequently than before given their increased accessibility and use in routine oncology practice, particularly in the upcoming feature. In the presence of unexplained elevations in acute phase parameters in a cancer patient on immune checkpoint inhibitor, it is a prevailing approach to perform a PET–CT imaging for scanning the aorta and its branches for vasculitis, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Johnson DB, Nebhan CA, Moslehi JJ, Balko JM. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 26] Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:254–267. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, Flores-Chávez A, Keegan N, Khamashta MA, Lambotte O, Mariette X, Prat A, Suárez-Almazor ME. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):38. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen P, Deng X, Hu Z, et al. Rheumatic manifestations and diseases from immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:762247. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.762247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostine M, Truchetet ME, Schaeverbeke T. Clinical characteristics of rheumatic syndromes associated with checkpoint inhibitors therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58(Suppl 7):vii68–vii74. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daxini A, Cronin K, Sreih AG. Vasculitis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors-a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(9):2579–2584. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crout TM, Lennep DS, Kishore S, Majithia V. Systemic vasculitis associated with immune check point inhibition: analysis and review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21(6):28. doi: 10.1007/s11926-019-0828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Wahab N, Shah M, Lopez-Olivo MA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of patients with cancer and preexisting autoimmune disease. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:133–134. doi: 10.7326/L18-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park HJ, Ranganathan P. Neoplastic and paraneoplastic vasculitis, vasculopathy, and hypercoagulability. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy AK, Tathireddy HR, Roy M. Aftermath of induced inflammation: acute periaortitis due to nivolumab therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017221852. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-221852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loricera J, Hernández JL, García-Castaño A, Martínez-Rodríguez I, González-Gay MÁ, Blanco R. Subclinical aortitis after starting nivolumab in a patient with metastatic melanoma. A case of drug-associated aortitis? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(2):171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hotta M, Naka G, Minamimoto R, Takeda Y, Hojo M. Nivolumab-induced periaortitis demonstrated by FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2020;45(11):910–912. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson D, Eslamian G, Poon D, Crabb S, Jones R, Sankey P, Kularatne B, Linch M, Josephs D. Immune checkpoint inhibitor induced large vessel vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(5):e233496. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-233496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ban BH, Crowe J, Graham RM (2017) Rheumatology case report immune-related aortitis associated with ipilimumab. Rheumatologist

- 14.Pinkston O, Berianu F, Wang B (2016) Type and frequency of immune-related adverse reactions in patients treated with pembrolizumab (Keytruda), a monoclonal antibody directed against PD-1, in Advanced melanoma at a single institution [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 68(suppl 10)

- 15.Zhang H, Watanabe R, Berry GJ, Vaglio A, Liao YJ, Warrington KJ, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Immunoinhibitory checkpoint deficiency in medium and large vessel vasculitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(6):E970–E979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616848114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe R, Zhang H, Berry G, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Immune checkpoint dysfunction in large and medium vessel vasculitis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312(5):H1052–H1059. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00024.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]