Abstract

Introduction:

Infectious diarrhea, a significant global health challenge, is exacerbated by flooding, a consequence of climate change and environmental disruption. This comprehensive study aims to quantify the association between flooding events and the incidence of infectious diarrhea, considering diverse demographic, environmental, and pathogen-specific factors.

Methods:

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, adhering to PROSPERO protocol (CRD42024498899), we evaluated observational studies from January 2000 to December 2023. The analysis incorporated global data from PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and ProQuest, focusing on the relative risk (RR) of diarrhea post-flooding. The study encompassed diverse variables like age, sex, pathogen type, environmental context, and statistical modeling approaches.

Results:

The meta-analysis, involving 42 high-quality studies, revealed a substantial increase (RR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.29–1.52]) in the incidence of diarrhea following floods. Notably, bacterial and parasitic diarrheas demonstrated higher RRs (1.82 and 1.35, respectively) compared to viral etiologies (RR = 1.15). A significant sex disparity was observed, with women exhibiting a higher susceptibility (RR = 1.55) than men (RR = 1.35). Adults (over 15 years) faced a greater risk than younger individuals, highlighting age-dependent vulnerability.

Conclusion:

This extensive analysis confirms a significant correlation between flood events and increased infectious diarrhea risk, varying across pathogens and demographic groups. The findings highlight an urgent need for tailored public health interventions in flood-prone areas, focusing on enhanced sanitation, disease surveillance, and targeted education to mitigate this elevated risk. Our study underscores the critical importance of integrating flood-related health risks into global public health planning and climate change adaptation strategies.

Key Words: Floods, Diarrhea, Disease transmission, infectious, Public health, Climate change, Risk factor

1. Introduction:

In the evolving landscape of global health threats, floods stand as a paramount concern, particularly in their role as catalysts for the spread of infectious diseases (1). Recognized as the most prevalent natural disaster, floods have left an indelible mark on human history, evidenced by catastrophic events such as the 1959 floods in China, the 1974 Bangladesh floods, and the 2004 Southeast Asian tsunami (2-4). The intensifying impact of climate change, manifesting in more frequent and severe flooding due to changing precipitation patterns and rising sea levels, necessitates a profound understanding of the resultant health consequences. This imperative drives the need for strategic public health measures and interventions tailored to these water-related catastrophes.

The relationship between flooding and public health is most evident in the increased incidence of infectious diarrhea following such events (5). The contamination of water sources during floods disrupts sanitary conditions and facilitates the transmission of various pathogens, leading to outbreaks of diarrheal diseases. This rise in disease incidence has been documented globally, indicating a consistent pattern of health crisis following major flooding events. The impact is particularly acute in areas with limited access to clean water and sanitation infrastructure, exacerbating the vulnerability of these populations (6-8).

Infectious diarrhea, caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites, is significantly influenced by flood conditions (9). Bacterial infections such as cholera and E. coli infection, along with parasitic infections like Cryptosporidium spp., have been closely linked to the aftermath of floods (10, 11). Controlling and managing these infections is critical, requiring timely and effective public health interventions. However, the recurrent and unpredictable nature of floods makes sustainable disease management a challenging task (12).

To date, a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis that fully encompasses the broad spectrum of diarrheal infections following flood incidents remains absent. Despite the scarcity of research in this domain, the existing literature serves as a pivotal foundation for understanding the epidemiological patterns of diarrheal diseases post-floods, yet it also highlights significant limitations. A detailed investigation by Lal et al. (2019) elucidated the association between diarrhea induced by Cryptosporidium spp. and various environmental factors, recognizing challenges such as biases in study selection, difficulties in generalizing findings across distinct local ecosystems, and the broader implications of climate change on disease prevalence (13). Similarly, Xin et al. (2021) examined the correlation between flood events and an escalated risk of dysentery in China, facing hurdles like the unquantifiable socioeconomic impacts, inadequate flood occurrence data, study heterogeneity, and reporting biases that complicate causal inferences (14). Levy et al. (2016) conducted a systematic review on the influence of meteorological phenomena on diarrheal diseases, contending with the integration of divergent data sources, an overemphasis on heavy rainfall to the exclusion of other relevant weather conditions, and the omission of sea surface temperature data pertinent to certain pathologies (15). Saulnier et al. (2017) offered a systematic analysis of health outcomes following flood and storm disasters, concentrating on diverse health issues including diarrheal diseases. They identified the variability in study designs and the quality of included studies as a major limitation, affecting the robustness and applicability of their findings to diarrheal outcomes post-disasters. Moreover, they noted the difficulty in directly linking flood and storm exposure to specific health outcomes due to the complex interplay of disaster impacts on health, encompassing indirect effects on sanitation and healthcare access (16).

So, our systematic review and meta-analysis aims to address this need by examining the relative risk (RR) of various types of diarrheal infections in the aftermath of flood events. By providing a detailed analysis of both the immediate and prolonged risks associated with different pathogens and considering the influence of environmental and demographic factors, this study seeks to deepen the understanding of the epidemiological trends of flood-related diarrheal diseases. We intend to overcome the limitations observed in the previous studies by broadening the scope of our search and including a wider range of diarrheal infections and causative agents. The ultimate goal is to provide information and improve public health protocols for managing these infections, particularly in the context of increasing flood events, thereby contributing to the preparedness and resilience of health systems and communities against this growing threat.

2. Methods:

2.1. Study design and setting

In compliance with the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines, this study was registered in PROSPERO (17), bearing the registration number 'CRD42024498899'. Studies reported in English between January 1, 2000, and December 1, 2023, which assessed diarrhea risk at least one week following a flood event were included for consideration. Only observational studies, including cohort, spatial ecology, case-control, cross-sectional and time-series studies, were included. These studies needed to be published as original research articles in peer-reviewed journals.

2.2. Comprehensive literature search strategy

Our methodology for the literature review stringently filtered observational studies quantifying the RR and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for post-flood diarrheal outbreaks. The scope of our review was limited to scholarly articles in English, sourced from prestigious databases including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and ProQuest, alongside grey literature accessed through Google and Google Scholar. Our search strategy was meticulously crafted, incorporating a comprehensive range of terms and their medical subject headings (MeSH) related to both flooding and diarrheal conditions. For a detailed illustration of our search strategy as applied in the PubMed database, refer to Table S1.

2.3. Study selection

Our selection methodology was guided by the PECOS (population, exposure, comparison, outcomes, and study design) criteria:

Population: Our analysis focused on human populations affected by flood events, without restrictions on age, sex, ethnicity, or socio-economic status.

Exposure: The primary exposure of interest was flooding events, defined as significant and sudden increases in water level due to heavy rainfall, dam breakages, or other hydrological phenomena leading to partial or complete inundation of normal dry land.

Comparison: The comparison was made between populations exposed to flooding events and those not exposed, within the same or different geographical regions, to ascertain the RR of developing diarrheal diseases post-exposure.

Outcomes: The primary outcome was the incidence of diarrheal diseases, with required reporting on RR and 95% CI or providing comprehensive data enabling these calculations. Secondary outcomes included risk variation across demographics (age and sex), pathogen types, time delays in disease manifestation during the initial week and/or from the second week forward, duration until resolution, climatic categorizations, diarrheal classifications, the utilization of diverse statistical models and the human development index (HDI) of the flood-affected region.

Exclusion criteria

We omitted studies that did not align with our precise parameters, including research on other natural disasters apart from floods or studies examining non-infectious diarrhea post-flood. Non-observational research formats, such as editorials, conference proceedings, and abstracts, reviews, books, theses, unstructured papers, proceeding papers and dissertations, as well as studies involving animals or employing in vitro/in silico methodologies, were systematically excluded. Moreover, research articles where raw data was inaccessible or where only abstracts were available without full text were also excluded from our analysis.

2.4. Data collection

The process of data extraction was meticulously conducted by two independent evaluators (M.S.Y. and M.A.A.). This involved a detailed scrutiny of titles and abstracts from the initially screened literature, aligned with the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. In instances of divergent opinions, a third adjudicator (M.C.) was brought in to reach a consensus. For the selected studies, an in-depth review of the entire text was performed. A bespoke data extraction template was employed for uniformity and accuracy in data collection. The extracted parameters included the lead author's name, year of publication, geographical location of the study, climatic categorization, duration of the study, diversity in diarrheal types, time lags in disease onset, resolution period, employed statistical models, the HDI of the region and the RR with their corresponding 95% CI. Additionally, the adjusted variables in each study were meticulously recorded to provide clarity on the context and adjustments of the reported associations. To assure the precision and reliability of our systematic review, both reviewers independently cross-verified the extracted data. This comprehensive process also included detailed documentation of pathogen types (bacteria, viruses, and parasites), study types, and demographic details (age and sex groups) involved in the studies.

2.5. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression

In our investigation, we undertook targeted subgroup analyses to delineate the RR of diarrhea across varied demographic profiles and environmental conditions, like age, sex, and the type of pathogen present. The objective was to delineate distinctive risk patterns that could elucidate the mechanisms of disease propagation in the aftermath of flooding events. Concurrently, we employed meta-regression techniques to systematically assess the impact of potential moderating variables on these risk associations, thereby providing a quantified analysis of the factors influencing disease dynamics.

2.6. Assessment of study quality and publication bias

The integrity and potential biases within the observational studies included in our meta-analysis were rigorously assessed by two independent reviewers (M.H. and M.Y.Z.). Conflicts among primary investigators were resolved through adjudication by a third party (R.M.). The evaluation process utilized the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies, focusing on selection, comparability, and outcome exposure. The NOS scores, ranging from 0 (lowest quality) to 9 (highest quality), facilitated the stratification of studies into categories reflecting their methodological quality. Further, to mitigate publication bias, we conducted both a visual assessment of funnel plots and applied Egger's regression test for a more formal evaluation of plot symmetry. As a sensitivity analysis, random trim and fill method was used in cases where the funnel plot was asymmetrical.

2.7. Sensitivity analysis

To validate the robustness of our findings, sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding studies identified as having a high risk of bias or those based on small sample sizes (< 400). This critical step ensured the reliability of our conclusions and the stability of the overall evidence base regarding the incidence of diarrhea associated with flood events.

2.8. Statistical analysis

We employed Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4 and Stata version 14 for the precise computation of pooled RRs via the inverse variance method, which consolidates the weighted means of the logarithmic transformations of individual study RRs and their 95% CIs. In our analysis, a preference was given to adjusted RRs to enhance the precision of our estimates and minimize potential biases, with all instances of unadjusted RRs explicitly indicated. The heterogeneity across studies was quantified using the I² statistic, which informed our selection of either fixed or random-effects models depending on the level of heterogeneity observed: 0% indicating no heterogeneity, ≤ 25% low, >25%–<75% moderate, and ≥75% high. In situations where moderate to high heterogeneity was detected, we conducted subgroup analyses and meta-regression to explore the sources of variability. For cases where RR values were not directly reported, we utilized a specific formula to determine the comparative risk of diarrhea among populations impacted by floods compared to those that were not: RR=

In this formula:

a represents the count of diarrhea cases in flood-affected zones.

b denotes the number of individuals without diarrhea in the same flood-affected areas.

c is the count of diarrhea cases in areas not affected by floods.

d indicates the number of non-diarrhea individuals in the non-affected areas.

This detailed methodology was supported by EndNote version 21 for reference management and data organization. This meticulous approach, complemented by a strict adherence to a statistical significance threshold (set at p-value < 0.05).

3. Results:

3.1. Study selection

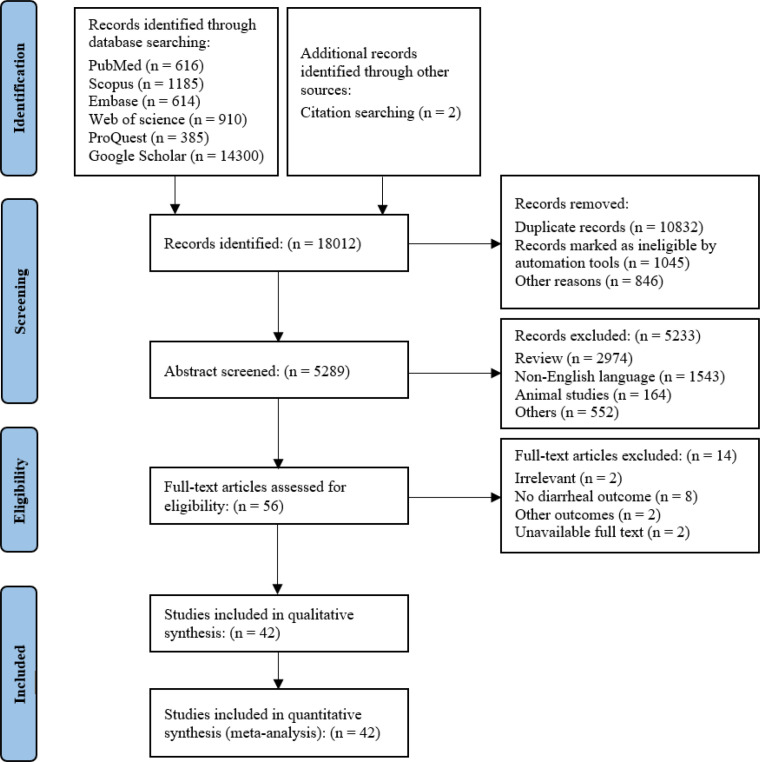

In an exhaustive initial search, 18,012 records were ascertained through multiple databases and ancillary sources. The subsequent deduplication process yielded 5,289 records amenable to the screening phase. Rigorous application of exclusion criteria, predominantly via automated tools and additional stipulations, resulted in the preclusion of 5,233 records from further consideration. A targeted assessment was conducted on 56 full-text articles. This evaluative phase culminated in the exclusion of 14 articles, with the underlying rationales comprehensively catalogued within the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Figure 1). Ultimately, a cohort of 42 studies (18-41) was distilled for qualitative synthesis; this subset was concurrently qualified for quantitative synthesis.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the selection of studies on flood-related infectious diarrhea.

3.2. Study characteristics

In our systematic review and meta-analysis, we scrutinized 42 peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2023, focusing on the role of floods in the spread of infectious diarrhea. This collection of studies provides a rich tapestry of research methodologies, encompassing 2 case-control studies (24), 3 cohort studies (19, 36), 4 cross-sectional studies (18, 22), 2 spatial ecological studies (39), and a majority of 31 time-series studies (21, 23, 25-35, 37, 38, 40-42). The geographical coverage of these studies is extensive, including 7 studies from Bangladesh (20, 22, 23, 36), with additional contributions from Brazil (24), Ghana (18), Peru (19), Vietnam (39), and China (25-35, 37, 38, 40-42). The resolution time analysis within these studies varies, incorporating 15 daily (18, 20, 21, 26, 27, 32, 35, 40), 17 monthly (19, 22, 24, 25, 28-31, 36-38), and 10 weekly studies (23, 30, 33, 39, 41, 42). The studies also reflect a diversity of climatic conditions, with 16 focusing on subtropical regions (26, 28-35), 13 in temperate climates (21, 25, 27, 37, 38, 40-42), and the remaining 13 in tropical areas (18-20, 22-24, 36, 39). Among the reviewed studies, 19 reported on watery diarrhea (18-24, 26, 36, 39), 10 on bacillary dysentery (25, 28, 30, 35, 42), 8 on bacillary dysentery combined with watery diarrhea (32, 34, 37, 40), 1 on dysentery alone (29), and 4 on a combination of dysentery with watery diarrhea (27, 33). Moreover, the statistical models employed in these studies varied including distributed lag non-linear models (DLNM) in 7 studies (30, 33-35), generalized additive mixed model (GAMM) in 11 studies (28, 29, 31, 36-38, 42), generalized linear models (GLM) in 11 studies (19, 21-23), generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) in 2 studies (39), with other models used in the remaining studies (18, 20, 24-27, 32, 40, 41). Notably, the research also delved into the RRs associated with different types of diarrheas, including bacterial (19, 20, 22, 23, 32, 34), viral (19, 22), parasitic (19), and non-infectious (22), as well as sex-specific risks, with 12 studies focusing on men (22, 23, 25, 27, 30, 35, 41) and 9 on women (23, 25, 27, 30, 35, 41). The temporal lag in diarrhea incidence following floods was examined, with 14 studies (19, 21, 23, 27, 28, 30-33, 35, 37, 38) examining risks within 7 days of a flood event, while others assessed longer-term impacts (18-30, 32-34, 36, 37, 39-42). Additionally, concerning the HDI of regions impacted by floods, 10 studies were conducted in areas with a medium HDI (18, 20, 22, 23, 36, 39), whereas the remaining investigations took place in regions classified at a high HDI level. (Table S2).

3.3. Quality assessment and risk of bias analysis

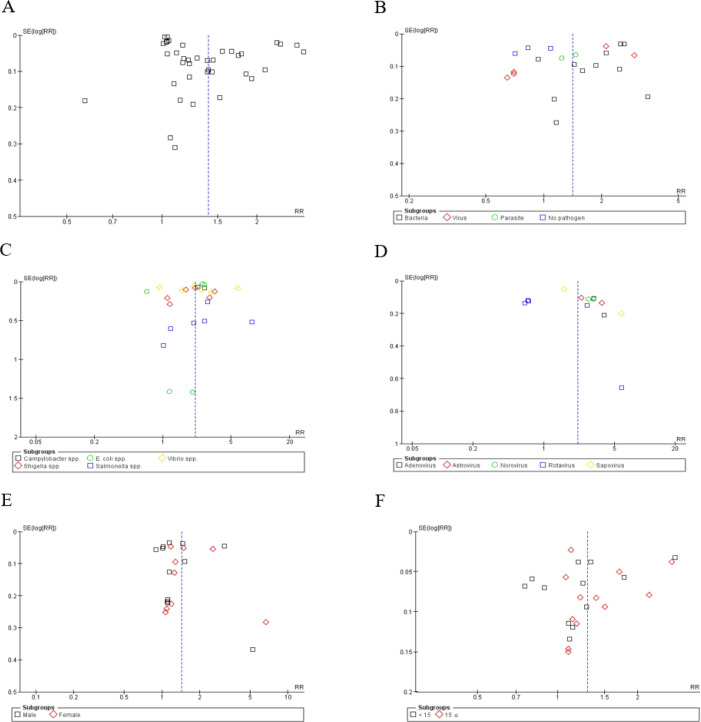

Our publication bias evaluation, using Egger's test and the Trim and Fill method, revealed potential bias (intercept 8.69, p-value = 0.005) across 42 studies. Despite this, the Trim and Fill method kept the pooled RR unchanged at 1.40 (95% CI [1.29, 1.52]). Bias was notable in studies with follow-ups over seven days, requiring 14 studies to be trimmed to adjust the RR to 0.98 (95% CI [0.79, 1.20]), whereas no bias was found in short-term studies (≤ 7 days), maintaining an RR of 1.31 (95% CI [1.11, 1.55]). Bias in monthly studies did not lead to adjustments; however, trimming two weekly studies adjusted the RR to 1.06 (95% CI [0.99, 1.14]). Tropical studies showed bias, corrected by trimming seven studies to an RR of 1.05 (95% CI [0.78, 1.33]). Cross-sectional studies showed bias (p-value = 0.029), adjusted by trimming to an RR of 1.10 (95% CI [0.88, 1.34]), and time-series studies, after trimming 13 studies, adjusted to an RR of 0.95 (95% CI [0.84, 1.07]) (Table S3). However, the sensitivity analysis underscored the robustness of our findings, indicating that no single study unduly influenced the meta-analysis results (Figure S1). Quality assessment using the NOS affirmed the high caliber of the included studies (Table 1), with most achieving top scores. The funnel plots, supplemented by Egger's test, confirmed these results, albeit with a slight asymmetry in the overall risk, suggesting a robust and reliable conclusion of increased diarrhea risks post-flooding (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Assessment of study quality and bias risk according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

| Study Reference | Selection (Out of 4) | Comparability (Out of 2) | Outcome (Out of 3) | Total Score (Out of 9) | Quality Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu et al. 2018 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Colston et al. 2020 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Colston et al. 2020 (1) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Emch 2000 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Gong et al. 2019 (1M) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Gong et al. 2019 (1S) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Gong et al. 2019 (2M) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Gong et al. 2019 (2S) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Harris et al. 2008 (1) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Harris et al. 2008 (2) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Harris et al. 2008 (3) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Hashizume et al. 2008 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Hashizume et al. 2008 (1) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Heller et al. 2003 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Hu et al. 2018 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Lan et al. 2022 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liao et al. 2020 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liao et al. 2020 (1) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liu et al. 2015 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liu et al. 2016 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liu et al. 2016 (1) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liu et al. 2017 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2017 (1M) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2017 (1S) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2017 (2M) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2017 (2S) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2019 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2019 (1) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Liu et al. 2018 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Liu et al. 2018 (1) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Luo et al. 2023 (M) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Luo et al. 2023 (S) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Ma et al. 2021 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Milojevic et al. 2012 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Ni et al. 2014 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Ni et al. 2014 (1M) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Ni et al. 2014 (1S) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Thompson et al. 2015 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Thompson et al. 2015 (1) | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Xu et al. 2017 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Zhang et al. 2016 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Zhang et al. 2019 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

M: Moderate floods: S = Severe floods

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for relative risk (RR) of A) overall diarrhea B) pathogenic and non-pathogenic diarrhea C) bacterial diarrhea D) viral diarrhea E) sex-specific diarrhea and F) age-specific diarrhea.

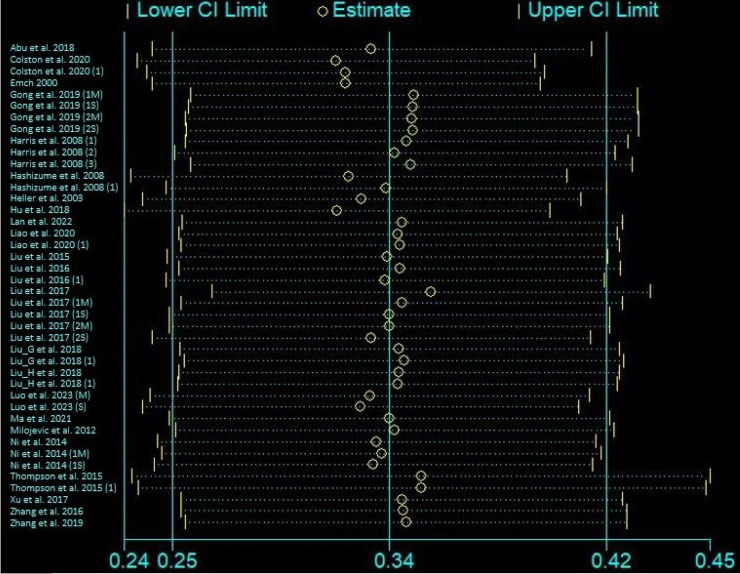

3.4. Meta-analysis

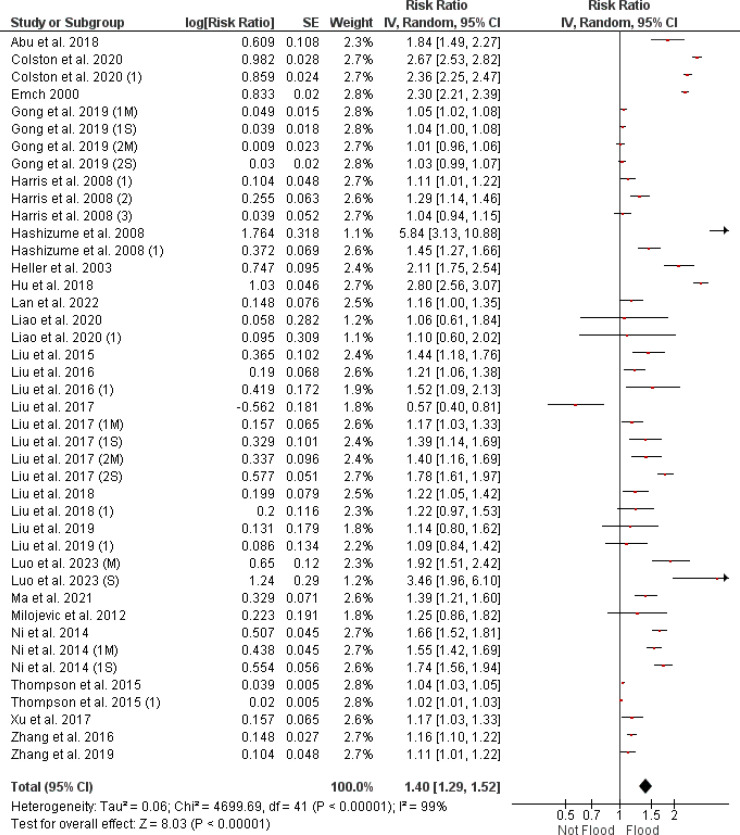

3.4.1. Impact of flooding on diarrhea risk

Figure 3 presents the RRs for diarrhea incidence following flood events, indicating an overall RR of 1.40 (95% CI [1.29, 1.52]) from the meta-analysis of 42 studies. Notwithstanding the indication of publication bias as suggested by the funnel plot in Figure 2A, the effect size remains unchanged and statistically significant after the trim and fill method adjustment (RR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.29, 1.52], as shown in and Table S3). The I² statistic is reported at 99%, and the overall effect has a p-value < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Forest plot depicting the relationship between flood exposure and risk ratio of infectious diarrhea, calculated using a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

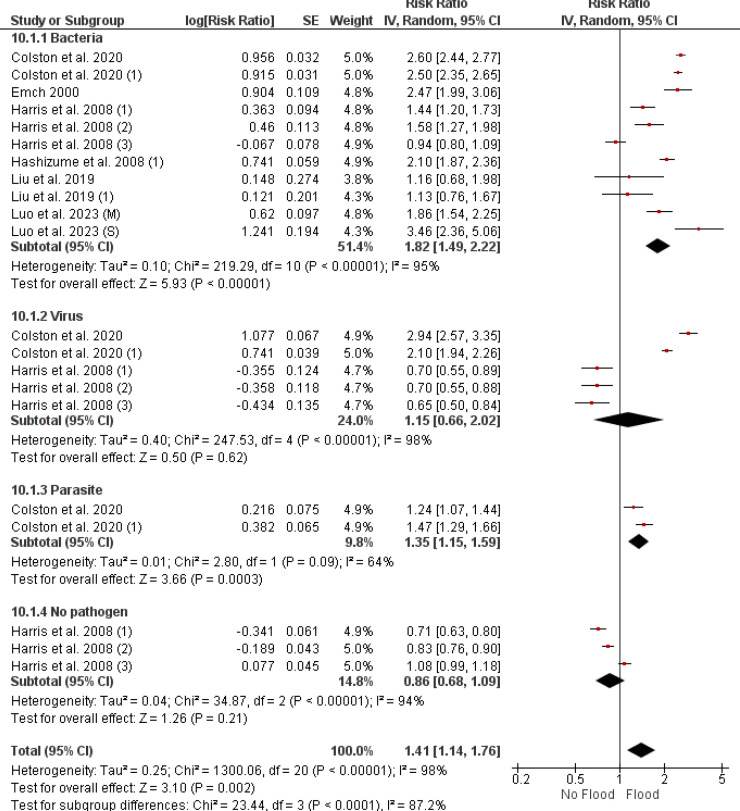

3.4.1.1. Differential impact of flooding on diarrheal diseases

Figure 4 outlines the varied effects of flood events on the RR of diarrheal diseases with bacterial, viral, parasitic, and non-pathogenic origins. The RRs with their 95% CIs are reported as follows: for bacterial diarrhea, the combined RR is 1.82 (95% CI [1.49, 2.22]), viral diarrhea has an RR of 1.15 (95% CI [0.66, 2.02]), while parasitic diarrhea shows an RR of 1.35 (95% CI [1.15, 1.59]). Non-pathogenic diarrhea has a combined RR of 0.86 (95% CI [0.68, 1.09]). I² values indicate substantial heterogeneity among studies: 95% for bacterial, 98% for viral, 64% for parasitic, and 94% for non-pathogenic diarrheas. The p-values for the overall effect are < 0.001 for both bacterial and parasitic diarrheas. Conversely, viral and non-pathogenic diarrheas do not show statistically significant associations.

Figure 4.

Forest plot depicting risk ratios for infectious versus non-infectious diarrhea in flood scenarios, analyzed using a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

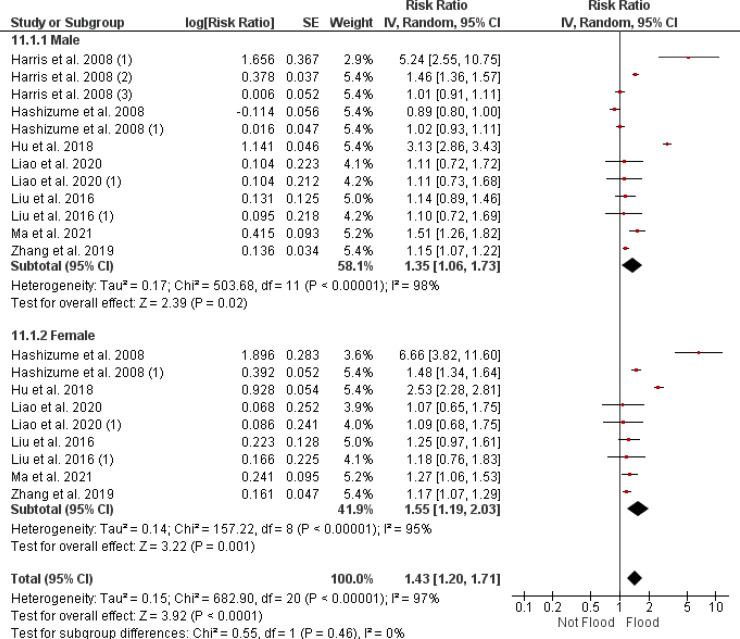

3.4.2. Sex-specific diarrhea risk following flood events

Figure 5 presents the RRs and 95% CIs for diarrhea incidence following flood events, disaggregated by sex. The meta-analysis shows an RR of 1.35 (95% CI [1.06, 1.73]) for males, with an overall effect p-value < 0.05. For females, the RR is reported at 1.55 (95% CI [1.19, 2.03]), with a p-value < 0.001, indicating statistical significance. The heterogeneity within the studies is high, as shown by I² values of 98% for males and 95% for females.

Figure 5.

A forest plot representation of the sex-specific risk ratios for infectious diarrhea associated with flooding, evaluated with a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

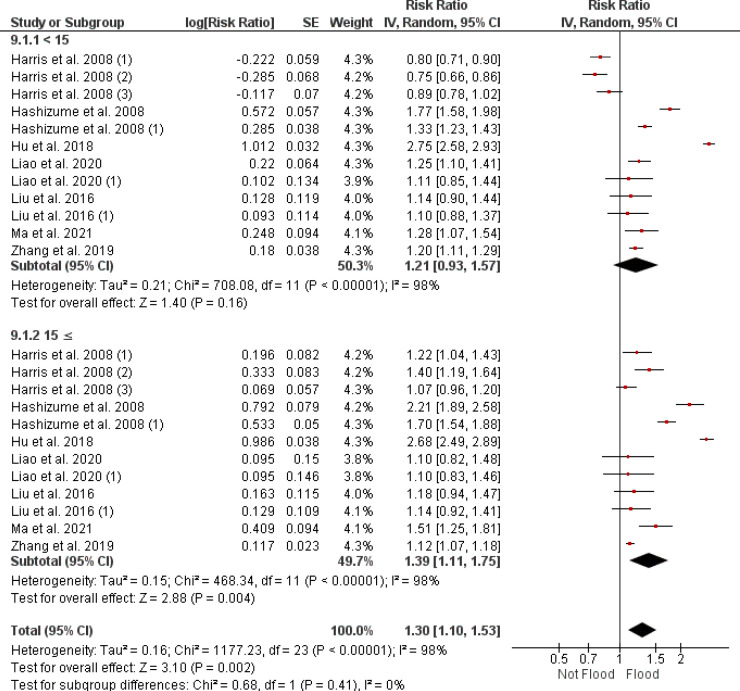

3.4.3. Age-related diarrhea risk following flood exposure

Figure 6 provides a stratified analysis of diarrhea risk after flooding, focusing on two age groups. For individuals under 15 years, the combined RR is 1.21 (95% CI [0.93, 1.57]). In contrast, those aged 15 years and above show a combined RR of 1.39 (95% CI [1.11, 1.75]). There is significant heterogeneity among the studies for both age groups, with an I² of 98%. The aggregated data indicate that the increase in risk for the younger age group is not statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.16, while the older age group's increased risk is significant with a p-value = 0.004.

Figure 6.

A forest plot presenting age-specific risk ratios for diarrhea in the aftermath of flooding, as determined through a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

3.4.4. Infectious diarrhea risk after flooding

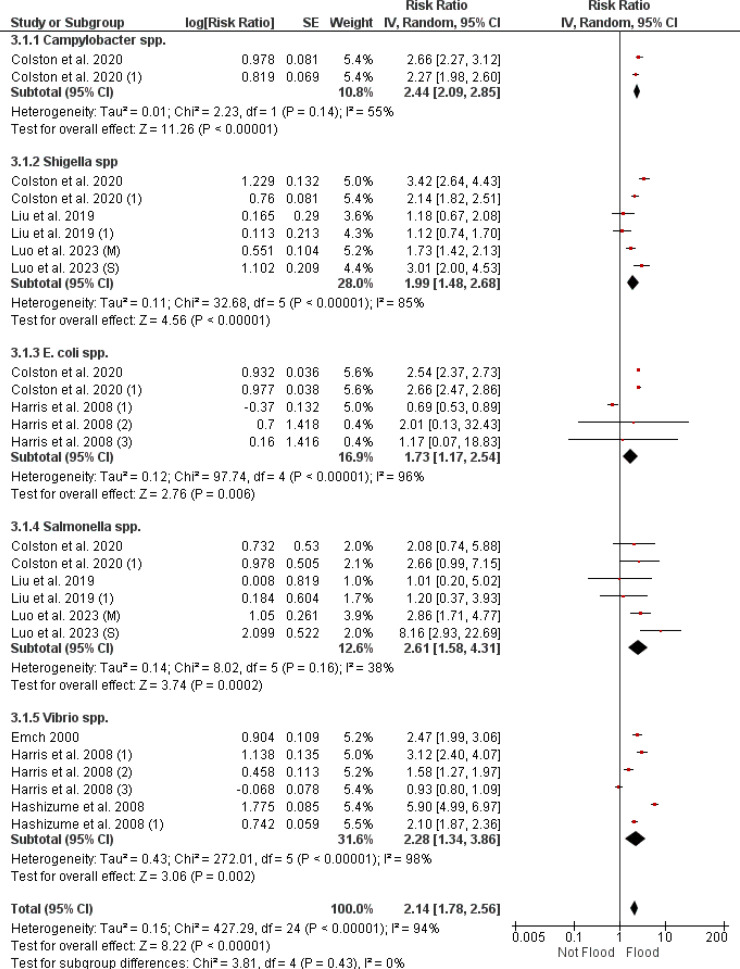

3.4.4.1. Bacterial diarrhea risk after flooding

Figure 7 presents a meta-analysis on the risk of bacterial diarrhea after flooding, examining specific bacterial pathogens. The RR for Campylobacter spp. is 2.44 (95% CI [2.09, 2.85]) with a heterogeneity of 55%. Shigella spp. have an RR of 1.99 (95% CI [1.48, 2.68]) and a heterogeneity of 85%. The RR for E. coli spp. is 1.73 (95% CI [1.17, 2.54]) with a heterogeneity of 96%. Salmonella spp. show an RR of 2.61 (95% CI [1.58, 4.31]) with a heterogeneity of 38%. For Vibrio spp., the overall RR is 2.28 (95% CI [1.34, 3.86]) with a heterogeneity of 98%.

Figure 7.

A forest plot showing the comparative risk ratios for various bacterial diarrheal infections following flooding, calculated through a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

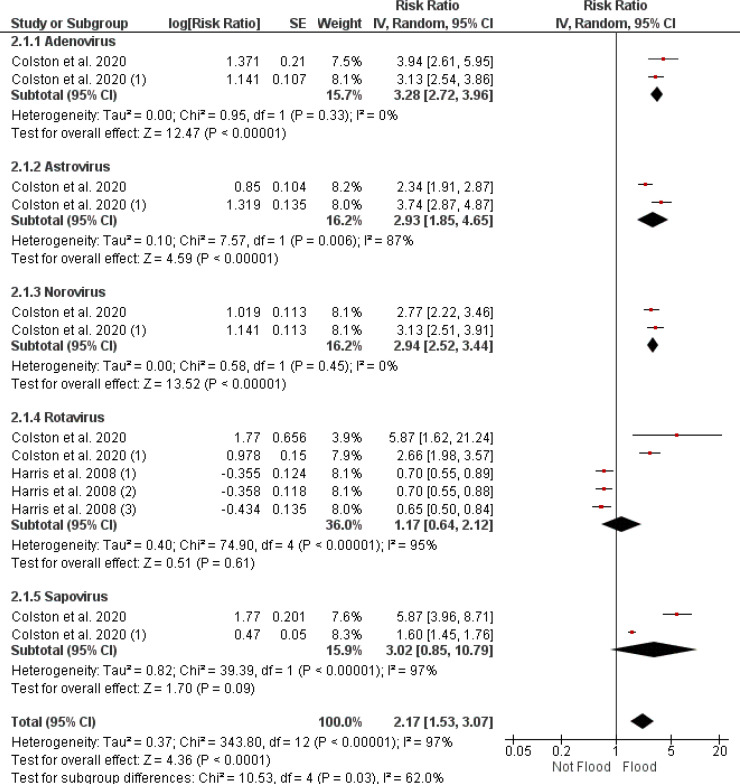

3.4.4.2. Influence of flooding on viral diarrhea risk

Figure 8 reports the RR of viral diarrhea following flood events, segmented by virus type. Adenovirus-related diarrhea has an RR of 3.28 (95% CI [2.72, 3.96]) with consistent findings across studies (I² = 0%). Astrovirus shows an increased RR of 2.93 (95% CI [1.85, 4.65]) with considerable heterogeneity (I² = 87%). The RR for norovirus stands at 2.94 (95% CI [2.52, 3.44]), again with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Rotavirus infections display a combined RR of 1.77 (95% CI [0.64, 2.12]), with notable heterogeneity (I² = 95%) and the p-value = 0.61. Sapovirus-associated RR is reported at 3.02 (95% CI [0.85, 10.79]), with substantial heterogeneity (I² = 97%) and a non-significant p-value = 0.09). The meta-analytic RR for all viral pathogens combined is 2.17 (95% CI [1.53, 3.07]), with an overall heterogeneity of 96%. The p-value for the combined viral pathogen risk is reported as p-value < 0.001.

Figure 8.

A forest plot detailing risk ratios for viral pathogens causing diarrhea after flooding, synthesized via a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

3.4.4.3. Post-flooding risk of parasitic diarrhea

Figure 9 of our meta-analysis report on the risk of parasitic diarrhea following flood events, focusing on Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. Cryptosporidium spp. shows an RR of 2.71 (95% CI [2.10, 3.49]) with low heterogeneity (I² = 6%). For Giardia spp., the RR varies with the timing of floods; in the late stage, an RR of 1.34 (95% CI [1.17, 1.54]) is reported, while the early stage shows an RR of 1.04 (95% CI [0.89, 1.22]) according to Colston et al. (2020) (19). The combined RR for Giardia spp., covering both periods, is 1.19 (95% CI [0.93, 1.52]), with high heterogeneity (I² = 82%). The overall RR for parasitic diarrhea after flooding is 1.74 (95% CI [1.17, 2.61]), with a p-value < 0.001.

Figure 9.

A forest plot summarizing the risk ratios for post-flood diarrheal illness caused by parasites, compiled using a random effects model. CI: confidence interval.

3.4.5. Delineation of diarrhea risk post-flooding through subgroup analysis

Our study conducts a subgroup analysis to explore the risk of diarrhea following flood events, focusing on various factors (Table 2). Temporal lag analysis indicates that risks are higher at an RR of 1.31 (95% CI [1.11-1.55]) within a week after flooding, increasing to 1.44 (95% CI [1.25-1.66]) for reports beyond one week. Despite evidence of publication bias within studies reporting a temporal lag > 7, as indicated by the funnel plot, the RR continued to be significant following the trim and fill adjustment. The adjusted RR was slightly lower but still substantial at 0.98 (95% CI [0.79, 1.20]), with the associated p-value remaining below the threshold of 0.001 (Table S3). Resolution time analysis yields RRs of 1.47 (95% CI [1.23-1.76]) for monthly, 1.12 (95% CI [1.08-1.17]) for weekly, and 1.32 (95% CI [1.11-1.56]) for daily resolutions. However, there is publication bias in the weekly subgroup, as seen by the funnel plot. The RR remained significant (RR = 1.06 (95% CI [0.99, 1.14]), p-value < 0.001, Table S3) even when the trim and fill approach was used. The subgroup analysis shows that subtropical regions have an RR of 1.27 (95% CI [1.13-1.43], tropical climates report an RR of 1.61 (95% CI [1.37-1.88]), and temperate climates have an RR of 1.20 (95% CI [1.11-1.31]). The existence of publication bias in the tropical area category is shown by the funnel plot. Following the implementation of the trim and fill method, although it still remained statistically significant (RR = 1.05 (95% CI [0.78, 1.33]), p-value < 0.001, Table S3). Also, the analysis indicates that all types of diarrhea studied show an increased RR, with bacillary dysentery having the RR of 1.53 (95% CI [1.28, 1.81]), followed by dysentery at 1.44 (95% CI [1.18, 1.76]), a combination of bacillary dysentery and watery diarrhea at 1.53 (95% CI [1.28, 1.81]), and watery diarrhea showing the RR at 1.39 (95% CI [1.24, 1.56]), all with high statistical significance as indicated by p-values < 0.001. The funnel plot reveals publication bias for watery diarrhea, yet the trim and fill-adjusted RR remains significant at 0.916 (95% CI [0.76, 1.08], p < 0.001, Table S3).

Table 2.

Comprehensive subgroup analysis of flood-associated infectious diarrhea

| Subgroups | No. of studies | RR [95% CI] | p-value of RR | I 2 (%) | p-value for heterogeneity | p-value for subgroup differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| < 15 | 12 | 1.21 [0.93, 1.57] | 0.16 | 98 | < 0.001 | 0.41 |

| ≥ 15 | 12 | 1.39 [1.11, 1.75] | 0.004 | 98 | < 0.001 | |

| Bacteria | ||||||

| Campylobacter spp. | 2 | 2.44 [2.09, 2.85] | < 0.001 | 55 | 0.14 | 0.43 |

| Shigella spp. | 6 | 1.99 [1.48, 2.68] | < 0.001 | 85 | < 0.001 | |

| E. coli spp. | 5 | 1.73 [1.17 ,2.57] | 0.006 | 96 | < 0.001 | |

| Salmonella spp. | 6 | 2.61 [1.58, 4.31] | 0.0002 | 38 | 0.16 | |

| Vibrio spp. | 6 | 2.28 [1.34, 3.86] | 0.002 | 98 | < 0.001 | |

| Virus | ||||||

| Adenovirus | 2 | 3.28 [2.72, 3.96] | < 0.001 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.03 |

| Astrovirus | 2 | 2.94 [1.85, 4.65] | < 0.001 | 87 | 0.006 | |

| Norovirus | 2 | 2.94 [2.52, 3.44] | < 0.001 | 0 | 0.44 | |

| Rotavirus | 5 | 1.17 [0.64, 2.12] | 0.61 | 95 | < 0.001 | |

| Sapovirus | 2 | 3.02 [0.85,10.79] | 0.09 | 97 | < 0.001 | |

| Parasite | ||||||

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 2 | 2.71 [2.10, 3.49] | < 0.001 | 6 | 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| Giardia spp. | 2 | 1.19 [0.93, 1.52] | 0.18 | 82 | 0.02 | |

| Temporal lag | ||||||

| ≤ 7 | 14 | 1.31 [1.11, 1.55] | 0.002 | 99 | < 0.001 | 0.39 |

| > 7 | 28 | 1.44 [1.25, 1.66] | < 0.001 | 99 | < 0.001 | |

| Resolution | ||||||

| Monthly | 17 | 1.47 [1.23, 1.76] | < 0.001 | 98 | < 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Weekly | 10 | 1.12 [1.08, 1.17] | < 0.001 | 89 | < 0.001 | |

| Daily | 15 | 1.32 [1.11, 1.56] | 0.001 | 99 | < 0.001 | |

| Climate group | ||||||

| Subtropical | 16 | 1.27 [1.13, 1.43] | < 0.001 | 81 | < 0.001 | 0.006 |

| Tropical | 13 | 1.61 [1.37, 1.88] | < 0.001 | 100 | < 0.001 | |

| Temperate | 13 | 1.20 [1.11, 1.31] | < 0.001 | 95 | < 0.001 | |

| Type of diarrhea | ||||||

| Watery | 19 | 1.39 [1.24, 1.56] | < 0.001 | 100 | < 0.001 | 0.21 |

| Bacillary dysentery | 10 | 1.36 [1.07, 1.74] | 0.01 | 97 | < 0.001 | |

| Bacillary dysentery + Watery | 8 | 1.53 [1.29, 1.81] | < 0.001 | 93 | < 0.001 | |

| Dysentery | 1 | 1.44 [1.18, 1.76] | 0.0003 | - | - | |

| Dysentery + Watery | 4 | 1.21 [1.07, 1.36] | 0.003 | 0 | 0.95 | |

| Statistical model | ||||||

| DLNM | 7 | 1.45 [1.23, 1.70] | < 0.001 | 76 | 0.0004 | < 0.001 |

| GAMM | 11 | 1.38 [1.22, 1.56] | < 0.001 | 88 | < 0.001 | |

| GLM | 11 | 1.43 [1.14, 1.79] | 0.002 | 99 | < 0.001 | |

| GLMM | 2 | 1.03 [1.01, 1.05] | 0.002 | 87 | 0.006 | |

| Other | 11 | 1.47 [1.13, 1.91] | 0.004 | 98 | < 0.001 | |

| Type of study | ||||||

| Case-control | 2 | 2.29 [2.20, 2.38] | < 0.001 | 0 | 0.38 | < 0.001 |

| Cohort | 3 | 2.29 [1.95, 2.69] | < 0.001 | 92 | < 0.001 | |

| Cross-sectional | 4 | 1.26 [1.05, 1.51] | 0.01 | 89 | < 0.001 | |

| Spatial ecology | 2 | 1.03 [1.01, 1.05] | 0.002 | 87 | 0.006 | |

| Time-series | 31 | 1.31 [1.20, 1.43] | < 0.001 | 96 | < 0.001 | |

| HDI level | ||||||

| Medium | 10 | 1.38 [1.21, 1.57] | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.89 | |

| High | 32 | 1.39 [1.23, 1.59] | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

HDI: Human Development Index; RR: Relative Risk; CI: Confidence Interval; DLNM: Distributed Lag Non-linear Models; GAMM: Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale, and Shape; GLM: Generalized Linear Models; GLMM: Generalized Linear Mixed Models

Different statistical models produced varied RRs: Distributed lag non-linear models (DLNMs) at 1.45 (95% CI [1.23-1.70]), generalized additive mixed effect models (GAMMs) at 1.38 (95% CI [1.22-1.56]), and generalized linear model (GLM) at 1.43 (95% CI [1.14-1.79]). The risk reported also varied by study design, with RR of case-control studies being at 2.29 (95% CI [2.20-2.38]), cohort studies at 2.29 (95% CI [1.95-2.69]), time-series at 1.31 (95% CI [1.20, 1.43]) and cross-sectional studies at 1.26 (95% CI [1.05-1.51]). Publication bias is evident in cross-sectional and time-series studies per the funnel plot. Post-trim and fill adjustment, the RRs were significant albeit lower at 1.10 (95% CI [0.88, 1.34]) and 0.95 (95% CI [0.84, 1.07]), respectively, with p-value < 0.001 (Table S3).

Also, the results pertaining to the HDI level demonstrate that for medium-HDI countries, the RR is 1.38 (95% CI [1.21, 1.57]), and for high HDI countries, the RR is 1.39 (95% CI [1.23-1.59]).

3.5. Meta regression analysis

In our study, a meta-regression model assessed the impact of different research variables on the risk of infectious diarrhea following flooding events. The time elapsed since flooding events showed no significant effect on diarrhea risk (β = -0.0837, p-value > 0.05). The variety of statistical models used across studies (β = -0.0260, p-value > 0.05) also did not significantly alter the risk estimates. Climate conditions were not a significant modifier of diarrhea risk (β = -0.0958, p-value > 0.05). The detail of data resolution, whether monthly, weekly, or daily, had no significant effect on the risk findings (β = 0.0737, p-value > 0.05). The clinical type of diarrhea, watery or dysenteric, was not associated with different levels of risk due to flooding (coefficient 0.0169, p-value > 0.05). Study design, including case-control and cohort studies, did not significantly influence the risk association (β = -0.0115, p-value > 0.05). Similarly, the HDI status did not significantly predict the risk of diarrhea, with a slight, non-significant decrease in risk as HDI status increased (β = -0.0162, p-value > 0.05).

4. Discussion:

The connection between floods and the rise of infectious diarrhea is a public health concern, highlighted by our meta-analysis of 42 studies. Our findings indicate a 40% increased risk of diarrhea in flood-affected regions (pooled RR of 1.40), reinforcing and expanding on earlier work by Heller et al. (2003) (24). Despite observing some publication bias initially, the adjustment with the trim and fill method left the total RR and its 95% CI unchanged and fully overlapping. We also observed that bacterial diarrhea risk (RR of 1.82) was higher than that for viral (1.15) and parasitic (1.35) diarrheas, supporting Luo et al. (2023)'s findings and suggesting that waterborne transmission is significant (43). Interestingly, non-pathogenic diarrhea risks did not rise post-flood, emphasizing that water contamination is a key factor in the spread of infectious agents during such events (44).

Our sex-specific analysis uncovered a crucial insight into how flooding differentially impacts infectious diarrhea risk between women and men. We found a higher risk for women, with a RR of 1.55, compared to 1.35 for men. This disparity suggests potential sex-related vulnerabilities and different levels of exposure or susceptibility to flood events, possibly due to societal roles, behavioral patterns, or biological differences. This observation is in line with other studies that have highlighted the unique challenges faced by women during natural disasters, including floods (45). Research by Sadia et al. (2014) demonstrated that women, often the primary caregivers and tasked with water collection and food preparation, are more susceptible to exposure to contaminated water during floods, increasing their risk of waterborne diseases (46). This increased risk could also reflect broader socio-economic and health disparities that worsen during disasters, as women in lower-income areas often have less access to healthcare resources and information, hindering their protection efforts during and after floods (47). These findings underscore the need for sex-sensitive public health planning and disaster management, advocating for interventions like targeted health education for women, equitable healthcare access post-disaster, and involving women in disaster planning and response (48). Despite the subgroup analysis of studies focusing on the HDI, and notwithstanding the increased risk of diarrhea in regions with high and medium HDI (p-value < 0.001), there was no notable distinction in the incidence between the two areas (p-value = 0.89).

Our study indicates an increased risk of infectious diarrhea among individuals over 15 years, challenging the conventional focus on children's vulnerability (41). This discrepancy could stem from adults' greater mobility and interactions with flood-impacted environments, such as through work or relief efforts, leading to increased exposure to contaminated water (49). This aligns with Alderman et al. (2012), who noted that adults' participation in outdoor flood-related activities could heighten their risk of waterborne diseases (50). Additionally, adults' health-seeking behaviors and existing health conditions might influence their vulnerability and response to diarrheal diseases after floods. While public health typically focuses on children's higher risk due to their developing immune systems and behaviors (51), our findings suggest a need for age-adjusted public health measures. Strategies should differ, with children's interventions focusing on hygiene and safe play, and adults on safe floodwater handling and quick access to healthcare. This elevated risk among adults emphasizes the necessity for inclusive flood management and public health strategies that address the diverse needs of all age groups, advocating for a broad approach to mitigate risks associated with floods.

Our meta-analysis provides a detailed understanding of how bacterial pathogens spread in flood conditions, with particular focus on Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp., which exhibit high RRs due to their waterborne transmission modes, intensified during floods (52, 53). These findings are consistent with the expected behavior of these pathogens in contaminated water following floods. However, the RRs for E. coli spp. show a distinct variability, from about 0.69 to 2.66, indicating a complex interplay of factors like strain characteristics, environmental conditions, and water and sanitation infrastructure quality that affect its spread during floods, albeit not as variably as previously thought (54, 55). This nuance in our understanding of E. coli transmission risks underlines the need for specific public health actions tailored to the pathogen's unique behavior in flood scenarios. It highlights the necessity of recognizing pathogen behavior diversity in response to environmental changes brought by flooding. Schwartz et al. (2006) support our conclusions, showing that the influence of flooding on waterborne disease transmission, like that caused by E. coli, can differ greatly based on local sanitation conditions, floodwater contamination levels, and public health system effectiveness (56). Our findings emphasize the need for adaptable public health strategies that address the particular transmission dynamics of E. coli in flood contexts, demanding a sophisticated approach to ensure effective management of these risks.

Our research highlights an increased risk for viral diarrheal diseases, specifically adenovirus and norovirus, underscoring their prominence in waterborne outbreaks during floods (57). These viruses are known for their durability in water and their potential to cause significant gastroenteritis outbreaks (58, 59). The observed rise in RRs for these viruses in flood conditions supports their efficient transmission through contaminated floodwaters, consistent with findings from other studies on waterborne diseases. La Rosa et al. (2017) provide evidence of noroviruses' ability to persist in water environments due to their low infectious dose and resilience to environmental pressures, leading to outbreaks after floods (60). Adenoviruses are similarly noted for their stability in water and have been linked to outbreaks where floods have affected sanitary conditions (61).

The notable variability in rotavirus risk ratios identified in our study suggests diverse regional transmission patterns and the influence of differing public health interventions (62). Rotaviruses, known for causing viral gastroenteritis primarily in children, have experienced shifts in epidemiology, largely due to the adoption of rotavirus vaccinations across various regions (63). This widespread vaccination effort may account for the observed variability in RRs, with regions having extensive vaccination coverage showing lower RRs compared to those with limited vaccination (64). This variation in risk is supported by Burnett et al. (2016), who found that rotavirus vaccination programs have significantly decreased disease incidence in certain areas, thereby affecting risk assessments in flood situations (65). The differential effectiveness of public health measures, including vaccination, sanitation practices, and flood management, appears to play a critical role in the diverse risk ratios seen for rotavirus.

Our study identifies a consistent increase in risk for parasitic infections, especially Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp., underscoring the challenge these pathogens present in flood conditions. Both parasites are notably resilient, thriving in harsh environments and thereby posing significant risks during floods due to water contamination (66). Cryptosporidium, causing cryptosporidiosis mainly in children, has a robust oocyst form that endures in water for extended periods (67). Giardia, leading to giardiasis, similarly withstands environmental pressures, persisting in water bodies and elevating transmission risk during floods (68). This aligns with their transmission characteristics and is supported by Efstratiou et al. (2017), who found flooding boosts the prevalence of these waterborne parasites in water systems (69). The study highlighted how floodwaters, contaminated with sewage and animal waste, facilitate the spread of Cryptosporidium and Giardia, triggering gastrointestinal illness outbreaks. Their survival capabilities in water and potential for causing long-lasting infections make these pathogens challenging to manage post-flood, emphasizing the need for comprehensive public health strategies focused on both immediate and prolonged responses, including sanitation enhancements to mitigate transmission risks.

Our study's temporal lag analysis highlights the dynamics of diarrheal disease risk following flooding, noting variable risks with a significant increase in the first week post-flood. This suggests a quick escalation in waterborne disease risk due to immediate water source contamination and sanitary disruption, aligning with findings from Alderman et al. (2012), who pointed out the swift impact of floods on spreading waterborne diseases (50). The influx of contaminants into water sources post-flooding calls for urgent public health actions, emphasizing the importance of immediate interventions such as providing safe drinking water, emergency sanitation, and rapid medical services to prevent disease outbreaks. Immediate public health messaging is also crucial, educating communities on the risks and preventive actions against waterborne diseases. Moreover, the observed variability in prolonged risks indicates the need for sustained efforts in monitoring water quality, maintaining sanitation, and educating the public to mitigate disease spread long after the initial flood event, underscoring the extended nature of flooding's public health impact.

Expanding on meta-regression analysis that highlights floods' widespread effect on diarrheal disease risk, our study broadens the discourse beyond the focused analyses by Lal et al. (2019) (13) and Xin et al. (2021) (14). Unlike Lal et al., who investigated cryptosporidiosis in children within specific socio-economic and environmental contexts, our research covers a wider spectrum of diarrheal diseases, including bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections. Xin et al.'s study, which looked at dysentery in China and observed an increased risk during flood periods, is complemented by our global analysis that not only aligns with their findings but also extends them by evaluating various diarrheal pathogens, resulting in RRs like 1.82 for bacterial and 1.35 for parasitic diarrhea. The broader geographic coverage and variety of diarrheal diseases examined in our study likely contribute to the observed higher RRs. Moreover, by directly associating flood events with an array of diarrheal diseases, our analysis offers a clearer insight into flooding's impact, distinguishing it from the more indirect approaches seen in previous research.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis offer detailed insights into the transmission dynamics of bacterial pathogens in floods, yet there are limitations affecting the generalizability of our findings. The included studies vary widely in terms of geography, demographics, and methodologies, enriching the data but potentially limiting global applicability. Differences in water and sanitation infrastructure quality across regions likely influence the RRs observed, complicating our results' interpretation. Additionally, publication bias and the exclusion of non-English studies may skew risk estimates and omit important data. However, the application of the trim and fill method has also partially addressed the issue of publication bias. Although, the subgroup analysis suggested that variations in time resolution, climate categorization, the statistical models applied, and the nature of the observational studies might be the principal contributors to publication bias. Furthermore, the observational nature of the studies underlying our analysis means we cannot definitively assert causality. The link between flooding and bacterial pathogen transmission, though indicative, requires cautious interpretation, as our observational data do not support the same level of inference as experimental research.

5. Conclusion:

Our comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis has elucidated a significant elevation in the risk of infectious diarrhea attributable to flooding events. This increase is particularly marked in bacterial and parasitic infections, underscoring the critical impact of such natural disasters on public health. Notably, the augmented risk observed in women and adults signifies demographic-specific susceptibilities that warrant focused attention. The findings from this global study transcend geographical boundaries and climatic variations, indicating the widespread and ubiquitous nature of flood-related health risks. Despite some heterogeneity in the data, the evidence strongly supports the necessity of developing and implementing robust public health strategies in anticipation of, and in response to, flood events. These strategies should prioritize the reinforcement of sanitation measures and the assurance of safe water supply to mitigate the heightened risk of infectious diseases post-flooding.

6.1. Funding

No funding was obtained for this study

6.2. Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

6.3. Author Contributions

Each participant in this study has played a pivotal role, beginning with the project's inception, through the design and implementation of the study, to the collection and examination of data, and its ultimate interpretation. Contributors have been actively involved in both the initial drafting and subsequent revisions of the manuscript, providing invaluable insights. The final manuscript, agreed upon by all, has been selected for submission to a mutually chosen journal, with every author jointly taking on the responsibility for the entire work's authenticity. Moreover, all authors assert that the manuscript is an original creation, free from any form of data fabrication, falsification, or unethical practices like image manipulation and plagiarism.

6.4. Data Availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

6.5. Acknowledgements

None.

6.6. Using artificial intelligence chatbots

None.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

PubMed search syntax for assessing health outcomes related to flooding

| Database | Search syntax |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (tsunami[tiab] OR rainfall*[tiab] OR flood*[tiab] OR "hydrological event*"[tiab] OR deluge*[tiab] OR torrent*[tiab] OR "high water"[tiab] OR "high tide"[tiab] OR stormwater*[tiab] OR waterlogging[tiab] OR "water logging"[tiab] OR "storm surge*"[tiab] OR inundation*[tiab]) AND (health[tiab] OR morbidit*[tiab] OR mortalit*[tiab] OR death*[tiab] OR sick*[tiab] OR illn*[tiab] OR wound*[tiab] OR injur*[tiab] OR accident*[tiab] OR disease*[tiab] OR disorder*[tiab] OR syndrome*[tiab] OR infection*[tiab] OR abnormalit*[tiab] OR trauma*[tiab] OR epidemi*[tiab] OR "side effect*"[tiab] OR "risk factor*"[tiab] OR outbreak*[tiab] OR "Frequency"[tiab] OR "Prevalence"[tiab] OR "Incidence"[tiab] OR "Spontaneous"[tiab] OR fever*[tiab] OR "water-related"[tiab] OR "water related"[tiab] OR "water-borne"[tiab] OR "water borne"[tiab] OR diarrhea[tiab] OR diarrhoea[tiab]) AND (protozoa [tiab] OR Giardia[tiab] OR Cryptosporidium[tiab] OR Salmonella[tiab] OR E.coli[tiab] OR cholera[tiab]) AND (2000/01/01:2023/09/30[dp]) |

Table S2.

Attributes of the selected studies

| Study | Type of study | Diarrhea | Climate group | Statistical model | Resolution | Country | HDI | RR (95% CI) | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu et al. 2018 | Cross-sectional | Watery | Tropical | Other | Daily | Ghana | Medium | 1.84 (1.5-2.27) | 2 months (November 2012- 31 December 2012) |

| Colston et al. 2020 | Cohort study | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Monthly | Peru | High | 2.67 (2.53-2.82) | 5 months (December 2011- May 2012) |

| Colston et al. 2020 (1) | Cohort study | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Monthly | Peru | High | 2.36 (2.25-2.47) | 5 months (December 2011- May 2012) |

| Emch 2000 | Case-Control | Watery | Tropical | Other | Daily | Bangladesh | Medium | 2.3 (2.21-2.4) | 36 months (January 1992-December 1994) |

| Gong et al. 2019 (1M) | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Temperate climate | GLM | Daily | China | High | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | 55 months (January 2013- August 2017) |

| Gong et al. 2019 (1S) | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Temperate climate | GLM | Daily | China | High | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 55 months (January 2013- August 2017) |

| Gong et al. 2019 (2M) | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Temperate climate | GLM | Daily | China | High | 1.05 (1.02-1.09) | 55 months (January 2013- August 2017) |

| Gong et al. 2019 (2S) | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Temperate climate | GLM | Daily | China | High | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | 55 months (January 2013- August 2017) |

| Harris et al. 2008 (1) | Cross-Sectional | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Monthly | Bangladesh | Medium | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) | 4 months (July- October 1998) |

| Harris et al. 2008 (2) | Cross-Sectional | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Monthly | Bangladesh | Medium | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) | 4 months (July- August 2004, September-October 2004) |

| Harris et al. 2008 (3) | Cross-Sectional | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Monthly | Bangladesh | Medium | 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | 3 months (July-September 2007) |

| Hashizume et al. 2008 | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Weekly | Bangladesh | Medium | 5.84 (3.13-10.88) | 10 months (July 1998- April 1999) |

| Hashizume et al. 2008 (1) | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Tropical | GLM | Weekly | Bangladesh | Medium | 1.45 (1.27-1.66) | 10 months (July 1998- April 1999) |

| Heller et al. 2003 | Case-Control | Watery | Tropical | Other | Monthly | Brazil | High | 2.11 (1.75-2.55) | 3.5 months (December 1993- April 1994) |

| Hu et al. 2018 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Temperate climate | Other | Monthly | China | High | 2.8 (2.54-3.08) | 60 months (2005-2009) |

| Lan et al. 2022 | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Subtropical | Other | Daily | China | High | 1.16 (1.0-1.34) | 36 months (2017-2019) |

| Liao et al. 2020 | Time-series Analysis | Dysentery & Watery | Temperate climate | Other | Daily | China | High | 1.1 (0.67-1.8) | 50 months (June 2013- August 2017) |

| Liao et al. 2020 (1) | Time-series Analysis | Dysentery & Watery | Temperate climate | Other | Daily | China | High | 1.06 (0.67-1.67) | 50 months (June 2013- August 2017) |

| Liu et al. 2015 | Time-series Analysis | Dysentery | Subtropical | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.44 (1.18-1.76) | 84 months (January 2004 - December 2010) |

| Liu et al. 2016 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | DLNM | Weekly | China | High | 1.21 (1.06-1.38) | 42 months (April 2005- September 2011) |

| Liu et al. 2016 (1) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | DLNM | Weekly | China | High | 1.52 (1.09-2.13) | 42 months (April 2005- September 2011) |

| Liu et al. 2017 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 0.57 (0.39-0.84) | 108 months (January 2004 - December 2012) |

| Liu et al. 2017 (1M) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.17 (1.03-1.33) | 108 months (January 2004 - December 2012) |

| Liu et al. 2017 (1S) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.39 (1.14-1.7) | 108 months (January 2004 - December 2012) |

| Liu et al. 2017 (2M) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.4 (1.16-1.69) | 108 months (January 2004 - December 2012) |

| Liu et al. 2017 (2S) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.78 (1.61-1.97) | 108 months (January 2004 - December 2012) |

| Liu et al. 2019 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Subtropical | Other | Daily | China | High | 1.14 (0.8-1.62) | 60 months (2006–2010) |

| Liu et al. 2019 (1) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Subtropical | Other | Daily | China | High | 1.09 (0.84-1.42) | 60 months (2006–2010) |

| Liu et al. 2018 | Time-series Analysis | Dysentery & Watery | Subtropical | DLNM | Weekly | China | High | 1.22 (1.05-1.42) | 96 months (2004- 2011) |

| Liu et al. 2018 (1) | Time-series Analysis | Dysentery & Watery | Subtropical | DLNM | Weekly | China | High | 1.22 (0.97-1.53) | 96 months (2004- 2011) |

| Luo et al. 2023 (M) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Subtropical | DLNM | Daily | China | High | 1.92 (1.51-2.42) | 60 months (May 2016- September 2020) |

| Luo et al. 2023 (S) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Subtropical | DLNM | Daily | China | High | 3.46 (1.96-6.1) | 60 months (May 2016- September 2020) |

| Ma et al. 2021 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Subtropical | DLNM | Daily | China | High | 1.39 (1.21-1.59) | 144 month (2005- 2016) |

| Milojevic et al. 2012 | Cohort study | Watery | Tropical | GAMM | Monthly | Bangladesh | Medium | 1.25 (0.86-1.82) | 6 months (August 2004- February 2005) |

| Ni et al. 2014 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Temperate climate | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.66 (1.52-1.82) | 72 months (2004 to 2009) |

| Ni et al. 2014 (1M) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Temperate climate | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.55 (1.43-1.68) | 72 months (2004 to 2009) |

| Ni et al. 2014 (1S) | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Temperate climate | GAMM | Monthly | China | High | 1.74 (1.56-1.94) | 72 months (2004 to 2009) |

| Thompson et al. 2015 | Spatial Ecological Study | Watery | Tropical | GLMM | Weekly | Vietnam | Medium | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | 72 months (2005- 2010) |

| Thompson et al. 2015 (1) | Spatial Ecological Study | Watery | Tropical | GLMM | Weekly | Vietnam | Medium | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 72 months (2005- 2010) |

| Xu et al. 2017 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery | Temperate climate | GAMM | Weekly | China | High | 1.17 (1.03-1.33) | 84 months (2004- 2010) |

| Zhang et al. 2016 | Time-series Analysis | Bacillary dysentery & Watery | Temperate climate | Other | Daily | China | High | 1.16 (1.1-1.22) | 84 months (January, 2005- December, 2011) |

| Zhang et al. 2019 | Time-series Analysis | Watery | Temperate climate | Other | Weekly | China | High | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) | 50.5 months (June, 2013- August 2017) |

HDI: Human Development Index, RR: Relative Risk, CIs: Confidence Intervals, DLNM: Distributed Lag Non-linear Models, GAMM: Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale, and Shape, GLM: Generalized Linear Models, GLMM: Generalized Linear Mixed Models

Table S3.

Evaluation of publication bias using Egger's Test and Trim and Fill method

| Egger's | Trim and fill method | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | No. of studies in each subgroup | intercept | p-value | Number of trimmed studies | Adjusted pooled RR (After trim) | p-value |

| Total (No subgrouping) | 42 | 8.69 | 0.005 | 0 | 1.40 [1.29, 1.52] | < 0.001 |

| Temporal lag | ||||||

| ≤ 7 | 14 | 7.95 | 0.126 | 0 | 1.31 [1.11, 1.55] | 0.002 |

| > 7 | 28 | 8.96 | 0.029 | 14 | 0.98 [0.79, 1.20] | < 0.001 |

| Resolution | ||||||

| Monthly | 17 | -15.72 | 0.010 | 0 | 1.61 [1.30, 1.92] | < 0.001 |

| Weekly | 10 | 4.67 | 0.022 | 2 | 1.06 [0.99, 1.14] | < 0.001 |

| Daily | 15 | 2.83 | 0.652 | 0 | 1.32 [1.11, 1.56] | < 0.001 |

| Climate group | ||||||

| Subtropical | 16 | -0.14 | 0.954 | 0 | 1.27 [1.13, 1.43] | < 0.001 |

| Tropical | 13 | 19.63 | 0.043 | 7 | 1.05 [0.78, 1.33] | < 0.001 |

| Temperate | 13 | 10.09 | 0.102 | 0 | 1.20 [1.11, 1.31] | < 0.001 |

| Type of diarrhea | ||||||

| Watery | 19 | 13.90 | 0.046 | 9 | 0.916 [0.76, 1.08] | < 0.001 |

| Bacillary dysentery | 10 | -14.02 | 0.102 | 0 | 1.36 [1.07, 1.74] | 0.01 |

| Bacillary dysentery + Watery | 8 | 5.09 | 0.176 | 0 | 1.53 [1.29, 1.81] | < 0.001 |

| Dysentery | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dysentery + Watery | 4 | -0.64 0.060 | 0 | 1.21 [1.07, 1.36] | 0.003 | |

| Statistical model | ||||||

| DLNM | 7 | 4.55 | 0.194 | 0 | 1.45 [1.23, 1.70] | < 0.001 |

| GAMM | 11 | -5.64 | 0.442 | 0 | 1.38 [1.22, 1.56] | < 0.001 |

| GLM | 11 | 12.94 | 0.383 | 0 | 1.43 [1.14, 1.79] | 0.002 |

| GLMM | 2 | -200.00 | - | 0 | 1.03 [1.01, 1.05] | 0.002 |

| Other | 11 | -5.46 | 0.057 | 0 | 1.47 [1.13, 1.91] | 0.004 |

| Type of study | ||||||

| Case-control | 2 | -200.00 | - | 0 | 2.29 [2.20, 2.38] | < 0.001 |

| Cohort | 3 | -6.53 | 0.644 | 0 | 2.29 [1.95, 2.69] | < 0.001 |

| Cross-sectional | 4 | 13.11 | 0.029 | 1 | 1.10 [0.88, 1.34] | < 0.001 |

| Spatial ecology | 2 | -2.53 | - | 0 | 1.03 [1.01, 1.05] | 0.002 |

| Time-series | 31 | 5.84 | 0.011 | 13 | 0.95 [0.84, 1.07] | < 0.001 |

| HDI level | ||||||

| Medium | 10 | 10.03 | 0.167 | 0 | 1.38 [1.21, 1.57] | < 0.001 |

| High | 32 | 1.52 | 0.721 | 0 | 1.39 [1.23, 1.59] | < 0.001 |

HDI: Human Development Index, RR: Relative Risk, CIs: Confidence Intervals, DLNM: Distributed Lag Non-linear Models, GAMM: Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale, and Shape, GLM: Generalized Linear Models, GLMM: Generalized Linear Mixed Models

Figure S1.

Forest plot for the sensitivity analysis

References

- 1.Angmor GDM. Climate Change Flooding And Diseases In Sub Sahara Africa: Trends And Adaptions Strategies (A Review) Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2024;28(1):8–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qian W, Lin X, Zhu Y, Xu Y, Fu J. Climatic regime shift and decadal anomalous events in China. Climatic Change. 2007;84:167–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery R. The Bangladesh floods of 1984 in historical context. Disasters. 1985;9(3):163–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang CS-k. Trajectory of traumatic stress symptoms in the aftermath of extreme natural disaster: A study of adult Thai survivors of the 2004 Southeast Asian earthquake and tsunami. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(1):54–9. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000242971.84798.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown L, Murray V. Examining the relationship between infectious diseases and flooding in Europe: A systematic literature review and summary of possible public health interventions. Disaster Health. 2013;1(2):117–27. doi: 10.4161/dish.25216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kouadio IK, Aljunid S, Kamigaki T, Hammad K, Oshitani H. Infectious diseases following natural disasters: prevention and control measures. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10(1):95–104. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baqir M, Sobani ZA, Bhamani A, Bham NS, Abid S, Farook J, Beg MA. Infectious diseases in the aftermath of monsoon flooding in Pakistan. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(1):76–9. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60194-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okaka FO, Odhiambo B. Relationship between flooding and out break of infectious diseasesin Kenya: A review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;2018:5452938. doi: 10.1155/2018/5452938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakim ST, Afaque F, Javed S, Kazmi SU, Nadeem SG. Microbial agents responsible for diarrheal infections in flood victims: a study from Karachi, Pakistan. Open J Med Microbiol. 2014;4(2):106–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols G, Lake I, Heaviside C. Climate change and water-related infectious diseases. Atmosphere. 2018;9(10):385. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shokri A, Sabzevari S, Hashemi SA. Impacts of flood on health of Iranian population: Infectious diseases with an emphasis on parasitic infections. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2020;9:e00144. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadarette SM. In: Effects of climate change on the epidemiology of flood-related waterborne disease: A Systematic Literature Review. Omaha (NE), editor. University of Nebraska Medical Center; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal A, Fearnley E, Wilford E. Local weather, flooding history and childhood diarrhoea caused by the parasite Cryptosporidium spp A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science Total Environ. 2019;674:300–6. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xin X, Jia J, Hu X, Han Y, Liang J, Jiang F. Association between floods and the risk of dysentery in China: a meta-analysis. Int J Biometeorol. 2021;65(7):1245–53. doi: 10.1007/s00484-021-02096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy K, Woster AP, Goldstein RS, Carlton EJ. Untangling the Impacts of Climate Change on Waterborne Diseases: a Systematic Review of Relationships between Diarrheal Diseases and Temperature, Rainfall, Flooding, and Drought. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(10):4905–22. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b06186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saulnier DD, Brolin Ribacke K, von Schreeb J. No Calm After the Storm: A Systematic Review of Human Health Following Flood and Storm Disasters. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(5):568–79. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X17006574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu K, Mei F, Gao Q, Zhao L, Chen F, Liu Q, et al. Assessment of whether published non-Cochrane systematic reviews of nursing follow the review protocols registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): A comparative study. bioRxiv. 2020;2020 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu M, Codjoe SNA. Experience and future perceived risk of floods and diarrheal disease in urban poor communities in Accra, Ghana. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2830. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colston J, Paredes Olortegui M, Zaitchik B, Peñataro Yori P, Kang G, Ahmed T, et al. Pathogen-specific impacts of the 2011–2012 La Niña-associated floods on enteric infections in the MAL-ED Peru Cohort: a comparative interrupted time series analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):487. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emch M. Relationships between flood control, kala-azar, and diarrheal disease in Bangladesh. Environ Plan A. 2000;32(6):1051–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong L, Hou S, Su B, Miao K, Zhang N, Liao W, et al. Short-term effects of moderate and severe floods on infectious diarrheal diseases in Anhui Province, China. Science Total Environ. 2019;675:420–8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris AM, Chowdhury F, Begum YA, Khan AI, Faruque AS, Svennerholm A-M, et al. Shifting prevalence of major diarrheal pathogens in patients seeking hospital care during floods in 1998, 2004, and 2007 in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79(5):708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashizume M, Wagatsuma Y, Faruque AS, Hayashi T, Hunter PR, Armstrong B, Sack DA. Factors determining vulnerability to diarrhoea during and after severe floods in Bangladesh. J Water Health. 2008;6(3):323–32. doi: 10.2166/wh.2008.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heller L, Colosimo EA, Antunes CMdF. Environmental sanitation conditions and health impact: a case-control study. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003;36(1):41–50. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822003000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu X, Ding G, Zhang Y, Liu Q, Jiang B, Ni W. Assessment on the burden of bacillary dysentery associated with floods during 2005–2009 in Zhengzhou City, China, using a time-series analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(4):500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan T, Hu Y, Cheng L, Chen L, Guan X, Yang Y, et al. Floods and diarrheal morbidity: Evidence on the relationship, effect modifiers, and attributable risk from Sichuan Province, China. J Glob Health. 2022;12:11007. doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao W, Wu J, Yang L, Benmarhnia T, Liang X-Z, Murtugudde R, et al. Detecting the net effect of flooding on infectious diarrheal disease in Anhui Province, China: a quasi-experimental study. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15(12):125015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Liu Z, Ding G, Jiang B. Projected burden of disease for bacillary dysentery due to flood events in Guangxi, China. Science Total Environ. 2017;601:1298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Ding G, Zhang Y, Xu X, Liu Q, Jiang B. Analysis of risk and burden of dysentery associated with floods from 2004 to 2010 in Nanning, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(5):925. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Z-D, Li J, Zhang Y, Ding G-Y, Xu X, Gao L, et al. Distributed lag effects and vulnerable groups of floods on bacillary dysentery in Huaihua, China. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):29456. doi: 10.1038/srep29456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Jiang B. The effects of floods on the incidence of bacillary dysentery in Baise (Guangxi Province, China) from 2004 to 2012. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):179. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, Ding G, Zhang Y, Lao J, Liu Y, Zhang J, et al. Identifying different types of flood–sensitive diarrheal diseases from 2006 to 2010 in Guangxi, China. Environ Res. 2019;170:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Z, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Li J, Liu X, Ding G, et al. Association between floods and infectious diarrhea and their effect modifiers in Hunan province, China: a two-stage model. Science Total Environ. 2018;626:630–7. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo P-y, Chen M-x, Kuang W-t, Ni H, Zhao J, Dai H-y, et al. Hysteresis effects of different levels of storm flooding on susceptible enteric infectious diseases in a central city of China. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1874. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16754-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Y, Wen T, Xing D, Zhang Y. Associations between floods and bacillary dysentery cases in main urban areas of Chongqing, China, 2005–2016: a retrospective study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021;26(1) doi: 10.1186/s12199-021-00971-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milojevic A, Armstrong B, Hashizume M, McAllister K, Faruque A, Yunus M, et al. Health effects of flooding in rural Bangladesh. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):107–15. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823ac606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ni W, Ding G, Li Y, Li H, Liu Q, Jiang B. Effects of the floods on dysentery in north central region of Henan Province, China from 2004 to 2009. J Infect. 2014;69(5):430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ni W, Ding G, Li Y, Li H, Jiang B. Impacts of floods on dysentery in Xinxiang city, China, during 2004-2010: A time-series poisson analysis. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23904. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson CN, Zelner JL, Nhu TDH, Phan MV, Le PH, Thanh HN, et al. The impact of environmental and climatic variation on the spatiotemporal trends of hospitalized pediatric diarrhea in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Health Place. 2015;35:147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, Liu Z, Gao L, Zhang C, Jiang B. Short-term impacts of floods on enteric infectious disease in Qingdao, China, 2005-2011. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(15):3278–87. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang N, Song D, Zhang J, Liao W, Miao K, Zhong S, et al. The impact of the 2016 flood event in Anhui Province, China on infectious diarrhea disease: An interrupted time-series study. Environ Int. 2019;127:801–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X, Ding G, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Liu Q, Jiang B. Quantifying the Impact of Floods on Bacillary Dysentery in Dalian City, China, From 2004 to 2010. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017;11(2):190–5. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moe CL. Waterborne transmission of infectious agents. Manual Environ Microbiol. 2007:222–48. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du W, FitzGerald GJ, Clark M, Hou X-Y. Health impacts of floods. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25(3):265–72. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00008141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erman A, De Vries Robbe SA, Thies SF, Kabir K, Maruo M. Gender dimensions of disaster risk and resilience: Existing evidence. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sadia H, Iqbal MJ, Ahmad J, Ali A, Ahmad A. Gender-sensitive public health risks and vulnerabilities’ assessment with reference to floods in Pakistan. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016;19:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava D, McGuire A. Patient access to health care and medicines across low-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cvetković VM, Roder G, Öcal A, Tarolli P, Dragićević S. The Role of Gender in Preparedness and Response Behaviors towards Flood Risk in Serbia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2761. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe D, Ebi KL, Forsberg B. Factors increasing vulnerability to health effects before, during and after floods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(12):7015–67. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10127015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alderman K, Turner LR, Tong S. Floods and human health: a systematic review. Environ Int. 2012;47:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pal M, Ayele Y, Hadush M, Panigrahi S, Jadhav V. Public health hazards due to unsafe drinking water. Air Water Borne Dis. 2018;7(1000138) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abulreesh HH, Organji SR, Elbanna K, Osman GEH, Almalki MHK, Ahmad I. Campylobacter in the environment: A major threat to public health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;7(6):374–84. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tracogna MF, Lösch LS, Alonso JM, Merino LA. Detection and characterization of Salmonella spp in recreational aquatic environments in the Northeast of Argentina. Rev Ambiente Água. 2013;8:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yard EE, Murphy MW, Schneeberger C, Narayanan J, Hoo E, Freiman A, et al. Microbial and chemical contamination during and after flooding in the Ohio River—Kentucky, 2011. J Environ Sci Health Part A. 2014;49(11):1236–43. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2014.910036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teague C. Assessing how rainfall and other environmental factors affect the level of E. coli contamination in two species of bivavle. Exeter (UK): University of Exeter; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz BS, Harris JB, Khan AI, Larocque RC, Sack DA, Malek MA, et al. Diarrheal epidemics in Dhaka, Bangladesh, during three consecutive floods: 1988, 1998, and 2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74(6):1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang X-Y, Su J, Lu Q-C, Li S-Z, Zhao J-Y, Li M-L, et al. A large outbreak of acute gastroenteritis caused by the human norovirus GI 17 strain at a university in Henan Province, China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40249-017-0236-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kauppinen A, Miettinen IT. Persistence of norovirus GII genome in drinking water and wastewater at different temperatures. Pathogens. 2017;6(4) doi: 10.3390/pathogens6040048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.La Rosa G, Sanseverino I, Della Libera S, Iaconelli M, Ferrero V, Barra Caracciolo A, Lettieri T. The impact of anthropogenic pressure on the virological quality of water from the Tiber River, Italy. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2017;65(4):298–305. doi: 10.1111/lam.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mena KD, Gerba CP. Waterborne adenovirus. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2009;198:133–67. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09647-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bennett A, Pollock L, Bar-Zeev N, Lewnard JA, Jere KC, Lopman B, et al. Community transmission of rotavirus infection in a vaccinated population in Blantyre, Malawi: a prospective household cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(5):731–40. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30597-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]