Abstract

Standard models of well-child care may not sufficiently address preventive health needs of immigrant families. To augment standard individual well-child care, we developed a virtual group-based psychoeducational intervention, designed to be delivered in Spanish as a single, stand-alone session to female caregivers of 0–6 month-olds. The intervention included a video testimonial of an individual who experienced perinatal depression followed by a facilitated discussion by the clinic social worker and an orientation to relevant community resources by a community health worker. To assess feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, we conducted an open pilot within an academic pediatric practice serving predominantly Latinx children in immigrant families. Participants included 19 female caregivers of infants attending the practice, of whom 16 completed post-intervention measures and 13 completed post-intervention semi-structured interviews. Quantitative measures of acceptability and satisfaction with the intervention were high. We found preliminary effects of the intervention on postpartum depression knowledge and stigma in the expected direction. In interviews, participants described increases in their familiarity with postpartum depression and about relevant community resources, including primary care for caregivers. Participants reported an appreciation for the opportunity to learn from other caregivers and provided suggestions for additional topics of interest.

Keywords: Well-child care, Postpartum Depression, Psychoeducation, Latinx, Immigrant

Background

Well-child care provides an important opportunity to identify and address family-level risk and protective factors. However, standard models of well-child care may be insufficient to address preventive health needs of many families. Children in immigrant families experience numerous health care disparities, including lower likelihood of identifying maternal depression, higher rates of food insecurity, and lower likelihood of having a medical home [1]. Therefore, alternative models of pediatric well-child care have been suggested.

One such model, group well-child care (GWCC), is associated with positive outcomes amongst children in immigrant families including high satisfaction and engagement, increased psychosocial screening, and increased time discussing psychosocial topics (e.g., postpartum depression, child behavior) [2]. However, its dissemination has been limited due to factors such as startup costs and clinic resources (e.g., need for staff to recruit patients/families and to coordinate scheduling) [2]. To address these challenges, and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and increase in use of telehealth modalities, we developed a less resource-intensive care (e.g., a single/stand-alone session could be offered monthly to all patients) virtual group-based intervention to augment standard individual well-child care. The intervention facilitates education/discussion around topics such as perinatal depression and community resources that had been identified as salient to the patient population.

Theoretical Framework

The intervention (Table 1) was informed by Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use [3] and was co-designed and co-facilitated by a bilingual/bicultural social worker and a community health worker. It includes a video testimonial featuring an individual who had experienced perinatal depression, previously developed for a mental health anti-stigma campaign.1

Table 1.

Intervention description

| Section of intervention & description | Time allotted2 | Facilitated by |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Staff introduction and discussion of session purpose Participant introductions: Name, age of children, country of origin |

5–10 min | Research & Clinic staff |

| Video (Berta’s story about perinatal depression) https://www.fortalecebaltimore.org/historias | 5 min | |

| Facilitated discussion of video • Participant reflections about video • Review prevalence and signs of PPD (la Depresión Posparto) • Review rationale for PPD screening in clinic • Review rationale for linkage to primary care for mother • Discussion about social support and self-care |

15 min | Clinic Social Worker |

| Review of community resources • Free/low-cost health care options for parents • Family planning resources • Free/low-cost mental health programming for parents • Domestic violence programming |

10 min | Clinic Community Outreach Specialist (CHW) |

| Review of entitlement programs • Insurance for children • Insurance for parents • Nutrition benefit programs • Identify challenges and plan for follow-up with clinic staff |

10 min | Clinic Community Outreach Specialist (CHW) |

| Summary/Wrap-up | 5 min | Research Staff |

For clinic staff: Training time was approximately 2 h total. Prepara-tory time was approximately 30 min per session.

Methods

Participants/Data Collection

We conducted an open pilot of the intervention within an academic pediatric practice serving predominantly Latinx children in immigrant families. Participants included 19 female caregivers (defined as parents or guardians) of infants attending the practice (see Table 2) who were identified/referred to the research team by clinic staff based on infant age (≤ 6 months) and preferred healthcare language (Spanish). Staff provided informational flyers to participants or asked permission for research staff to contact participants.

Table 2.

Baseline participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Full sample n = 19 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Race, n(%) White |

9 | (47.5%) |

| Multiracial | 1 | (5.0%) |

| Other | 9 | (47.5%) |

| Mean maternal age, y (SD) | 33.4 | (6.5) |

| Limited English Proficiency1, n(%) | 18 | (95.0%) |

| Country of Origin, n(%) El Salvador |

5 | (26.0%) |

| Guatemala | 3 | (16.0%) |

| Honduras | 4 | (21.0%) |

| Ecuador | 2 | (11.0%) |

| Mexico | 5 | (26.0%) |

| Mean time in US, y (SD) | 11.5 | (5.7) |

| Mean # children in household, M(SD) | 2.6 | (1.1) |

| Monthly family income, n(%) <$833 |

4 | (21.0%) |

| $834–1,667 | 1 | (5.0%) |

| $1,667–2,500 | 5 | (26.0%) |

| $2,500–3,333 | 2 | (10.5%) |

| $3,334–4,167 | 3 | (15.5%) |

| >$4,167 | 2 | (10.5%) |

| Did not report or unknown | 2 | (10.5%) |

| Maternal Education, n(%) Eighth grade or less |

13 | (68.0%) |

| Some high school | 3 | (16.0%) |

| High school | 3 | (16.0%) |

| Family Structure, n(%) Single |

2 | (10.0%) |

| Spouse or Partner | 17 | (90.0%) |

| Mean Perceived Social Support3, M(SD) | 5.3 | (1.3) |

| Food Insecure2, n(%) | 11 | (50.0%) |

| Food Assistance, n(%) WIC |

17 | (89.0%) |

| SNAP | 7 | (37.0%) |

| Have own primary care provider, n (%) | 7 | (37.0%) |

| 7 | (37.0%) | |

| 7 | ||

| Ever had mental health treatment, n (%) | 5 | (26.0%) |

English proficiency was measured using US Census Bureau question, “How well do you speak English?” with any answers below “very well” considered Limited English Proficiency (LEP)

Food insecurity was assessed with 2-question Hunger Vital Sign screener (Hager et al., 2010), affirmative response to either question indicates household risk for food insecurity

Scores range from 1–7, with higher scores indicating higher perceived support

Nine stand-alone sessions were delivered between June 2022-April 2023, with group sizes ranging from 1 to 4. Pre- and post-intervention surveys (collected within 2 weeks of intervention attendance) were administered over the phone in Spanish by bilingual research staff. Participants were also invited to a post-intervention qualitative interview and were remunerated for completion of surveys and interviews. The study was approved by the [Blinded] IRB and was pre-registered (NCT05423093).

Measures

At baseline, participants provided demographic information (see Table 2) and completed the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support2[4]. Pre-post surveys included 1) the 3-item Stigma Concerns about Mental Health Care3 [5] measuring stigma-related barriers to accessing and using depression treatment (summed for a depression treatment stigma score; 2) the Personal Stigma Scale3 [5], adapted for this study to include 7 items averaged for a score of attitudes towards people with PPD3) the 4-item PROMIS Self-Efficacy to Manage Emotions-Short Form3 [6] measuring level of confidence to manage emotions in response to stressors (averaged for a self-eficacy to manage emotions score; and 4) a yes/no question assessing PPD knowledge: “Have you heard of the phrase postpartum depression?”3 An 8-item satisfaction questionnaire developed for this study4 and a 4-item acceptability questionnaire4 [7] were administered post-intervention. Brief semi-structured interviews were conducted post-intervention to obtain more in-depth intervention feedback.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis included descriptive statistics of key variables and exploratory paired samples t-tests to examine change in self-reported mental health stigma variables (depression treatment stigma and attitudes toward people with PPD), self-efficacy to manage emotions, and depression knowledge. Qualitative analysis used thematic analysis [8]. Two bilingual coders listened to interviews independently, taking initial notes on themes. One coder then transcribed and translated recordings, questions about translations were reviewed with a third study team member who was a native Spanish speaker. After initial transcript review, a preliminary list of codes was created, including a priori codes based on interview questions and emerging themes. Coders re-reviewed transcripts to apply preliminary codes and subsequently met to discuss discrepancies in coding, further refine and re-apply codes, and discuss themes and connections between codes.

Results

Sample Characteristics

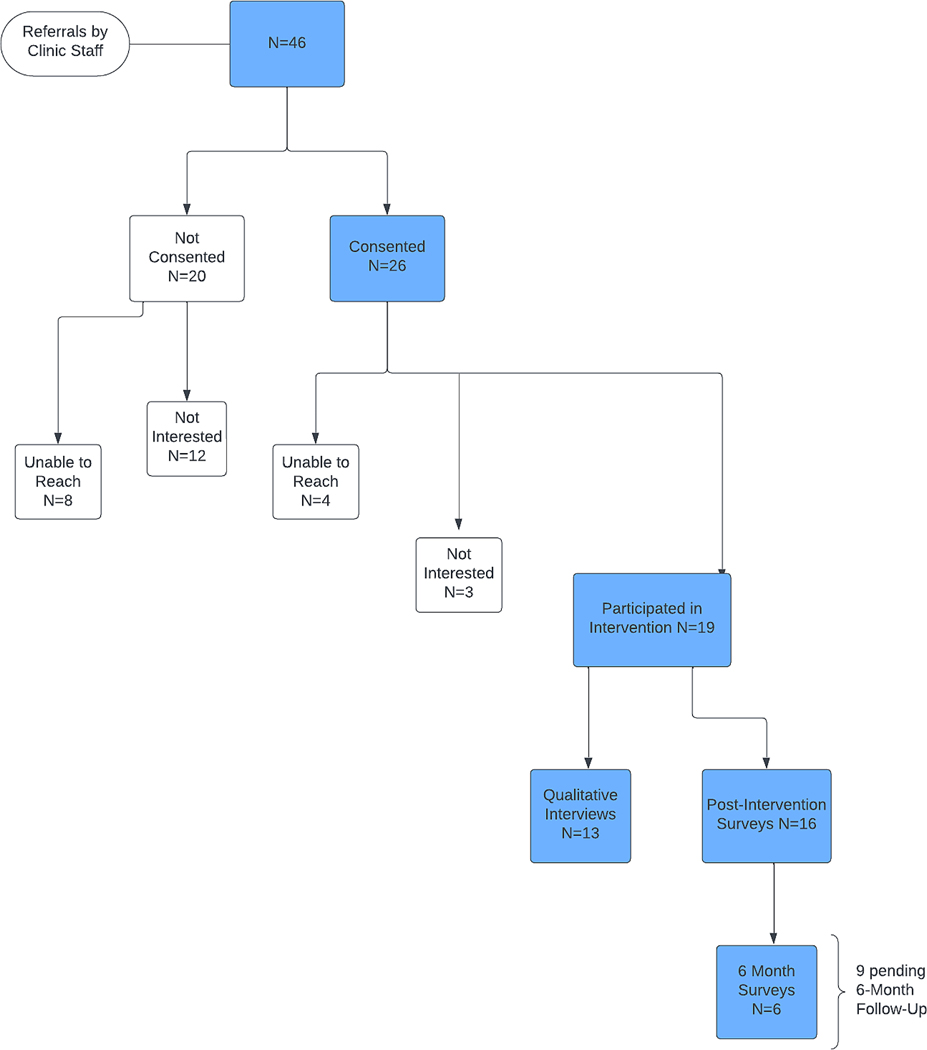

Figure 1 summarizes participant referral and study participation. Results below include the 19 participants completing the intervention, 16 completing post-intervention assessments, and 13 completing interviews.

Fig. 1.

Referral and Participation Flowchart

Quantitative Outcomes

Means and standard deviations for key study variables are presented in Table 3. Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant increase from pre- to post-intervention in mean attitudes toward people with PPD, t (14) = −3.51, p = .02, Cohen’s d = − 0.91, representing a shift toward more positive personal views of people with PPD. Additionally, there was a marginally significant reduction in mean levels of stigma towards depression treatment, t (15) = 1.73, p = .052. Participants’ self-efficacy for managing emotions showed a trend towards increasing, but pairwise comparisons were not statistically significant (p > .05). PPD knowledge increased significantly, with 75% of the sample reporting familiarity with the term “postpartum depression” before the intervention and 94% reporting familiarity with the term following intervention completion, t (15) = −1.86, p = .04, Cohen’s d = − 0.47. On average, participants were highly satisfied with the intervention (4.06 on a 5-point scale, individual items shown in Table 4) and found the intervention to be highly acceptable in its delivered format (4.17 on a 5-point scale).

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | n | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1. Soc Support T1 | -- | 19 | 5.32 | 1.33 | ||||||||

| 2. Dep Tx Stigma T1 | − 0.18 | -- | 19 | 0.89 | 1.20 | |||||||

| 3. Dep Tx Stigma T2 | − 0.38 | 0.49 | -- | 16 | 0.50 | 0.97 | ||||||

| 4. Attitudes PPD T1 | 0.11 | − 0.47* | − 0.70** | -- | 18 | 2.85 | 0.31 | |||||

| 5. Attitudes PPD T2 | 0.28 | − 0.50* | − 0.59* | 0.71** | -- | 16 | 3.12 | 0.45 | ||||

| 8. SE Emot T1 | 0.54* | − 0.35 | − 0.22 | − 0.04 | 0.26 | -- | 19 | 3.38 | 0.65 | |||

| 9. SE Emot T2 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.06 | − 0.39 | − 0.17 | -- | 16 | 3.39 | 0.49 | ||

| 10. Satisfaction | 0.38 | − 0.19 | − 0.26 | 0.14 | − 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.29 | -- | 16 | 4.06 | 0.49 | |

| 11. Acceptability | 0.21 | − 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.16 | -- | 16 | 4.17 | 0.34 |

| PPD Knowledge T1 | 19 | 63% | -- | |||||||||

| PPD Knowledge T2 | 16 | 94% | -- | |||||||||

Note. Soc. Support = Perceived Social Support, scores range from 1–7, higher scores indicate higher perceived support; Dep Tx Stigma = Depression Treatment Stigma as measured by Stigma Concerns about Mental Health Care questionnaire, total scores range from 0–3, higher scores indicate increased internalization of stigma to mental health care; Attitudes PPD = Attitudes toward people with post-partum depression (PPD), Average item scores range from 1–5, higher scores indicate higher levels of depression stigma; SE Emot = Self-efficacy for managing emotions, scores range from 1 to 5, higher scores indicate higher self-efficacy. Satisfaction: average item score. Items and scoring described in Table 4. Acceptability: average item score, scores range from 1–5, higher scores indicate higher acceptability

PPD Knowledge = % answering yes to question “Have you heard of the phrase postpartum depression?”

T1 = time 1 (pre-intervention); T2 = time 2 (post-intervention)

p < .05.

p < .01

Table 4.

Item-level satisfaction with intervention

| Post-Session Satisfaction (n = 16) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| This session helped me to… | ||

| Prepare to share my concerns with my child’s health provider | 4.0 | 0.89 |

| Learn about services available in this clinic | 4.25 | 0.45 |

| Learn about services available in my community | 4.25 | 0.45 |

| Learn about postpartum depression | 4.06 | 0.68 |

| Understand why it is important for this clinic to ask me about postpartum depression at my baby’s appointment | 4.19 | 0.75 |

| Learn about ways to take care of myself | 4.0 | 0.63 |

| Connect with other parents in my community | 3.63 | 0.89 |

| I would recommend this session to other first-time mothers who come to this clinic | 4.13 | 0.34 |

Note. Respondents rated items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree)

Qualitative Interview Themes

Codes were categorized into three overarching themes described below and displayed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of qualitative interview themes and exemplar quotes

| Theme | Description/Subthemes | Exemplar Quotes (corresponding subtheme) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Expanding Knowledge | Participants described learning about: | |

| Participants described learning about: a) Postpartum depression and how to ask for help |

a) Learning about PPD I learned how to try to understand, if this [postpartum depression] were to happen to me (although it hasn’t); I would know what to do and where to go, who I can call. [Just] knowing that there is someone there to help me if I start to feel like this [is helpful]. |

|

| b) Health and social resources in the community | b) Learning about health and social resources in the community I didn’t know about the resources that provided free/discounted services. The resource list was important because I don’t have a medical doctor to take care of my ane-mia. There was a lot of information on how to receive discounts so I can be seen by someone. I called already to schedule an appointment. It was easy to call and schedule because I found someone who spoke Spanish. |

|

| c) Self-care/communication within individual cultural context | c) Learning about self-care/communication within individual cultural context The most important thing is communication and I think this is something we sometimes lack, especially us as Latinas, because we are accustomed to a culture of “machista” marriages where you don’t feel free to express yourself. But, through these resources we are reminded that we have a voice and a vote, and we have a right. We are free to express ourselves as we’d like. |

|

| Sharing/Shared Experiences | Participants described: | |

| a) Shared experiences (for example, identifying with other participants or with the woman in the video) | a) Sharedexperiences Good, because you share. Every mom, every family, every baby, is a different experience. [Whether] you have other children or you are a first-time mom, it always serves you well to have these conversations [about shared experiences]. Sometimes people feel the same way that the woman felt in the video. | |

| b) Sharing experiences (the process of sharing experiences with and learning from peers) | b) Sharing experiences [It] was over an hour and yet it felt very short. I think it was because we were all “conviviendo” and sharing with other people. Sometimes we don’t have anyone to talk to, we don’t have family. Sometimes we need the opportunity to talk, to unburden ourselves. For me it was really interesting. |

|

| Feedback and Recommendations | Participants provided feedback about: | |

| a) Format of the session, describing both benefits and drawbacks of the virtual group format. | a) Feedback about session format/content/processesSometimes you have to care for the baby, and you can’t really pay attention to the session. I would have liked to communicate with other moms and have conversations with them but unfortunately that was not the case. I don’t know what happened. It would have been interesting because, first, you can make new friends, and second, you can get their numbers, keep talking, ask when you have doubts. But, I haven’t had that opportunity yet. In my case I am a little reserved when discussing things. One, because I don’t like to share my personal life, but with a psychologist I could talk with her and tell her this is what’s happening. Sometimes the topics are delicate, and we don’t want to discuss it with others. But with a psychologist we could talk, and they could give advice, I think it would be important. |

|

| b) Recommended additional topics, including health resources for children, infant behavior, and nutrition, and how to care for oneself in the context of multiple family obligations. | b) Recommendations for additional topics The health of the children is very important because sometimes we ask where do you recommend a dentist for the baby or an ophthalmologist. Sometimes we don’t know where to go. Each baby is different. I would love to hear about each experience for each mom. For example, my first baby ate every hour, and my second baby prefers to sleep more instead of eating, so nutrition is different for him…things like that. For my first baby I was a first-time mother, and I didn’t know many things, like exercises like tummy time and things to stimulate the baby. The only thing I can say for sure is that these topics are really important. I know that there are many women, not only Hispanics, there are men that are very “machista,” they can leave the house at whatever time but not me, I have to stay here while the kids are small, I have to help them. But who thinks about me? So, it would be very good to focus on this, how to help yourself because there aren’t options when they are little. I can’t say I’m going to leave my children [when] my husband is like this. There are men that help their wives with cooking, but my husband doesn’t even know how to cook an egg, nothing. |

|

Expanding Knowledge

Participants described learning about a range of topics in sessions. With respect to PPD, some described gaining awareness of its existence and prevalence, others described increased familiarity with potential PPD symptoms and the importance of symptom disclosure. Nearly all participants described identifying with the video testimonial and increasing their familiarity with community resources. Several reported being previously unfamiliar with health care resources for uninsured individuals and as a result of their participation, accessed their own primary care or family planning services. One participant linked increased awareness of community resources with decreased stress. Several expressed interest in sharing session information with others in their community.

Sharing/Shared Experiences

Most participants expressed appreciation for the opportunity to share experiences with other mothers, whether those experiences related to challenges caring for newborns and managing older children, or challenges accessing health care services. Several described sessions as an opportunity to alleviate isolation related to being a new parent and/or a recent immigrant. One participant noted that the session provided opportunity for self-expression, a liberty she rarely felt she had due to gender roles and cultural expectations. Several participants also described learning from other mothers through distinct cultural traditions and others’ experiences as parents.

Feedback and Recommendations

Participants described both benefits and drawbacks of the virtual group format. Benefits included convenience and time; several noted that not having to leave the house with a newborn or arrange childcare was helpful. Conversely, others expressed interest in meeting other mothers and seeing their babies in-person. Several expressed a desire for more mothers to attend sessions and opportunities to learn more about the other participants. Nearly all participants expressed an interest in attending additional sessions in the future. Most expressed interest in additional discussion topics (e.g., child development, child behavior, parenting).

Discussion

We describe preliminary acceptability and outcomes from a virtual group session (including a video testimonial about PPD) for Spanish-speaking caregivers attending pediatric primary care. The intervention goal was to augment primary care for infants in immigrant families, where providers have a unique opportunity to address salient family risk factors (e.g., access to health care, health literacy) and promote protective factors (e.g., social support) [1]. Overall, participants described the intervention as acceptable, with preliminary effects on PPD knowledge and stigma in the expected direction. Qualitatively, participants reported increased knowledge about PPD and relevant community resources, including primary care for caregivers. An emphasis on access to primary care for children in immigrant families may be an increasingly relevant link in access to treatment for PPD in the context of policies focused on expanding insurance eligibility in the postpartum period [9].

There are several study limitations. Intervention delivery occurred at a single site and was only delivered in Spanish, limiting generalizability. Recruitment was limited by clinic staff turnover, diminished clinic capacity during the study and lack of interest or time amongst potential participants. We note small group sizes, which has implications for feasibility and may have influenced intervention outcomes. The sample size and lack of comparison group limit our ability to draw conclusions about intervention effects or explore subgroup effects. There may also have been desirability bias related to research staff involvement in the intervention and data collection.

New Contribution to the Literature

Despite these limitations, we describe preliminary acceptability of a low-intensity intervention (including a freely available educational video testimonial about perinatal depression) to address inter-related health care needs and augment well-child care for Latinx families. Future studies should refine the intervention/study design based on the science of single-session interventions [10] and examine implementation across sites.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Isabella Perea, Ariana Tovar, and Annette Faria for their assistance with the research study described in this manuscript. Production of the website/video described in the intervention was funded by the Leonard & Helen R Stulman Charitable Foundation.

Funding

Work completed by Dr. Platt, Ms. Richman and Dr. Caroline Martin was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH118431, PI: Platt). Creation/Production of the website/video described in the intervention was funded by the Leonard & Helen R Stulman Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Declarations

Conflict of Interest The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Video available at www.fortalecebaltimore.org/historias.

Measure has been validated in Spanish.

Measure professionally translated for this study.

References

- 1.Linton JM, Choi R, Mendoza F. Caring for children in immigrant families: vulnerabilities, Resilience and opportunities. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(1):115–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gresh A, et al. A conceptual Framework for Group Well-Child Care: A Tool to Guide implementation, evaluation, and Research. Matern Child Health J. 2023;27(6):991–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.RM A. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimet GD, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grieb SM, et al. Mental Health Stigma among Spanish-speaking latinos in Baltimore, Maryland. J Immigr Minor Health. 2023;25(5):999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruber-Baldini AL, et al. Validation of the PROMIS(®) measures of self-efficacy for managing chronic conditions. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(7):1915–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner BJ, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hettinger K, Margerison C. Postpartum Medicaid Eligibility Expansions and Postpartum Health Measures. Popul Health Manag. 2023;26(1):53–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schleider JL, Beidas RS. Harnessing the single-Session intervention approach to promote scalable implementation of evidence-based practices in healthcare. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:997406. 10.3389/frhs.2022.997406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]