Abstract

Background

Radical oophorectomy was first performed by Hudson in order to remove an "intact ovarian tumour lodged in the pelvis, with the entire peritoneum remaining attached". We report 16 cases of radical oophorectomy done at our institute in the past 3 years and have analysed the perioperative morbidity as well as feasibility of performing the surgery without much of perioperative complication.

Methods

Twenty-three patients with advanced ovarian cancer who underwent modified en bloc pelvic resection at our institute, between November 2018 and October 2021, were initially enrolled. Patients below 70 years, resectable disease on CT scan and no significant comorbidities were included. Exclusion criteria were extra-abdominal metastasis, secondary cancers or complete intestinal obstruction. Initially, 23 patients were enrolled out of which seven patients were excluded. Hence, a total of 16 patients with ovarian cancer extensively infiltrating into nearby pelvic organs and peritoneum were included. In Type 1 radical oophorectomy, retrograde modified radical hysterectomy alongwith in toto removal of the bilateral adnexae, pelvic cul-de-sac and affected pelvic peritoneum is done. Type 2 radical oophorectomy includes total parietal and visceral pelvic peritonectomy as well as an en bloc resection of the rectosigmoid colon below the peritoneal reflection.

Results

Radical oophorectomy is feasible with acceptable complication rate. In our study, only one patient had burst abdomen that too due to the poor nutritional status of the patient. There was no surgery-related deaths, but one patient succumbed to pulmonary embolism 5 days after the operation.

Conclusion

Hence, radical oophorectomy proves to be an effective, feasible and secure surgical technique in cases of advanced ovarian malignancies with extensive involvement of peritoneum, pelvis and visceras.

Keywords: Radical oophorectomy, Epithelial ovarian cancer, Hudson method, En bloc pelvic resection

Background

Amongst the newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients, most of them are diagnosed in an advanced stage, making it the most common cause of death from gynecologic malignancy [1]. Primary cytoreductive surgery, followed by chemotherapy, is the currently recommended course of treatment for ovarian carcinoma [2]. Numerous studies show that patients who were optimally cytoreduced had better survival rate than those who underwent suboptimal cytoreduction [3–6]. Whether or not to perform a thorough cytoreductive procedure depends on the likelihood of removing all visible disease [7]. In order to fully debulk advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients with extensive disease in pelvic and visceral organs, an en bloc pelvic resection is performed [8].

In toto pelvic resection of ovarian tumour alongwith rectosigmoid colectomy was initially reported in 1968 and 1973 separately by Hudson and Chir, which was labelled as “radical oophorectomy”. Radical oophorectomy was first performed by Hudson in order to remove an "intact ovarian tumour lodged in the pelvis, with the entire peritoneum remaining attached". Subsequently, 25 cases (23 with cancer) undergoing the procedure between 1965 and 1972 were reported by Hudson [9].

Reverse hysterocolposigmoidectomy, modified posterior exenteration, en bloc pelvic peritoneal resection [10], en bloc rectosigmoid colectomy and complete parietal and visceral peritonectomy [11] are some of the other terminologies for the modified procedures used in the described surgical method [9].

In Type 1 radical oophorectomy, retrograde modified radical hysterectomy alongwith in toto removal of the bilateral adnexae, pelvic cul-de-sac and affected pelvic peritoneum is done. Type 2 radical oophorectomy includes total parietal and visceral pelvic peritonectomy as well as an en bloc resection of the rectosigmoid colon below the peritoneal reflection. A part of the bladder with or without pelvic ureter is included in a Type 3 radical oophorectomy, which is an annexure of a Type 1 or Type 2 resection.

Here, we report 16 cases of radical oophorectomy done at our institute in the past 3 years and have analysed the perioperative morbidity as well as feasibility of performing the surgery without much of perioperative complication.

Aims and Objectives

The present study was performed with the objective to evaluate the outcomes and morbidities in advanced ovarian cancer patients who have undergone radical oophorectomy.

Subject and Methods

In this retrospective observational analysis, medical records of our institute were searched for the patients who have undergone radical oophorectomy between November 2018 and October 2021. Twenty-three patients with advanced EOC who underwent modified en bloc pelvic resection at the Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Acharya Harihar Post Graduate Institute of Cancer (AHPGIC), Cuttack, between November 2018 and October 2021, were initially enrolled. Age under 70, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance level 0 or 1, resectable illness determined by computed tomography (CT) scan, absence of severe comorbidities and written consent were the inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria were extra-abdominal metastasis, other organ parenchymal involvement leading to organ resections, other malignant pathologies, active infections or complete intestinal obstruction and those who did not give consent to participate. Out of those 23 patients, seven patients were excluded. Patients excluded was one patient who had a history of carcinoma breast 10 years back, was treated for the same and had now presented with ovarian cancer, one patient had splenic parenchymal deposit so splenectomy had been done alongwith Type 1 radical oophorectomy, three patients did not give consent for the study and another two patients were lost to follow-up and could not be contacted. Patients undergoing only radical hysterectomy are not included in this study. Hence, a total of 16 patients were included in this study. Figure 1 depicts the complete methodology of the study.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting the detailed methodology of the study

An en block pelvic resection was the prescribed course of action. A circumscribing peritoneal incision is used to commence the en bloc pelvic resection technique and includes all pan-pelvic illness within this circumferential incision. The round and infundibulopelvic ligaments are ligated and cut following retroperitoneal pelvic dissection. The ureters are separated from the peritoneum and mobilised. The urinary bladder is mobilised down, and the vesicovaginal space is created after the anterior pelvic peritoneum overlying the bladder and its tumour nodules have been dissected caudally. At the level of the ureters, the uterine arteries are divided, and the parametrium is resected. Retrograde hysterectomy is done. The tumour and peritoneum can be detached from the anterior surface of the rectum and the sigmoid colon by sharp dissection in Type I modification of radical oophorectomy, if there is only superficial involvement of the tumour to the rectum. If the tumour only partially (2 cm) invades the muscularis of the rectum, a wedge-shaped section of the rectal wall can be excised and reconstructed, using a fine monofilament suture in interrupted inverting stitches that incorporate minimum mucosa and are positioned perpendicular to the long axis of the colon. In Type 2 radical oophorectomy alongwith the steps mentioned in Type 1 radical oophorectomy, an en bloc resection of the rectosigmoid colon below the peritoneal reflection is performed. The pelvis remains macroscopically disease-free when the specimen is removed in one piece along with the uterus, adnexa, pelvic peritoneum, rectosigmoid colon (Type 2) and tumour deposits. This procedure is a part of primary surgery, which utilised several types of peritonectomy together with associated resections to remove all visible disease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Type of peritonectomy

| Types of peritonectomy | Additional resections | No. of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic peritonectomy | Uterus, adnexae and rectosigmoid colon | 16 |

| Upper quadrant peritonectomy | omentectomy | 14 |

| Diaphragmatic stripping | 2 | |

| Subcapsular liver deposits resection | 1 | |

| Complete parietal peritonectomy | 7 | |

| Anterior parietal wall peritonectomy | Previous abdominal incisions | 0 |

| Umbilical metastatic deposits | 1 | |

| Types of lymphadenectomy | Selective BPLNs/PALNS | 3 |

| Systematic PALND/PALNS | 11 |

Statistical Analysis

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel sheet. SPSS version 22 was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages while continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

There were 16 patients altogether that were included in this study. Patients age ranged from 32 to 67 years, with a mean age of 47.18 years. The body mass index (BMI) ranged from 19 to 31 kg/m2 with a median of 26.2 kg/m2. The most common histological type was high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), which was found in 8 out of 16 (or 50%) cases. In 9 out of 16 patients (56.2%), the most prevalent International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage was IIIC confirmed. There were only three patients with ascites that were more than 1000 ml (18.75 per cent). Table 1 provides comprehensive information on the pre-treatment and disease-related features. Tables 2 and 3 display operative details. 14/16 cases lymph node dissection had been done, rest two cases nodal dissection had not been done. The surgery and hospital stay each had median durations of 240 min (within a range of 180–280 min) and 8 days (between 7 and 28 days), respectively. The median estimated blood loss (EBL) was approximately 500 ml. Blood transfusions have been given to all 16 patients. The average number of transfusions of red blood cells (RBCs) was two (range: 0–4 units). The average number of days spent in the ICU was only 1 day (range: 1–4 d). Six patients experienced perioperative complications. Two patients had subacute intestinal obstruction (SAIO), one patient had burst abdomen and two patients had superficial surgical site skin infection (SSSI). There were no any complications specifically related to this procedure. One woman died suddenly 5 days after surgery, but there were no surgery-related deaths. Although all patients received postop thromboprophylaxis, her death was caused due to pulmonary embolism. Platinum-based treatment was administered to the rest 15 individuals who survived. The median interval between the initial operation and the beginning of the chemotherapy treatment was 35 days (interval: 21–42 days) (range: 6–28 months). The median follow-up time was 14 months. Throughout the period of surveillance, there were no cases of recurrence in any of the patients.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features

| Clinicopathologic feature | Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 32–67 years | 47.18 years (mean) |

| BMI (mean) | 19–31 | 26.2 |

| ECOG | 0 | 7 |

| 1 | 9 | |

| 2 | 0 | |

| Type of surgery | Primary | 7 |

| IDS | 9 | |

| Tumour histology | HGSOC | 8 |

| LGSOC | 1 | |

| Endometriod | 5 | |

| Mucinous | 1 | |

| Clear cell | 1 | |

| FIGO stage | 2b | 2 |

| 3b | 4 | |

| 3c | 9 | |

| 4a | 1 | |

| Ascites | < 1 L | 3 |

| > 1 L | 3 | |

| Nil | 10 |

Table 3.

Intraoperative and perioperative details

| Case no. | Duration (mins) | EBL (ml) | ICU (days) | Hospital stay (days) | BT (units) | Perioperative complications | Time interval between CRS and CHT (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 250 | 700 | 3 | 10 | 4 | Caecal seromuscular injury | 40 |

| 2 | 180 | 500 | 1 | 8 | 2 | SAIO | 30 |

| 3 | 200 | 600 | 2 | 9 | 2 | No | 35 |

| 4 | 180 | 500 | 1 | 8 | 2 | No | 38 |

| 5 | 190 | 500 | 1 | 8 | 2 | No | 40 |

| 6 | 270 | 600 | 2 | 15 | 3 | SAIO | 42 |

| 7 | 210 | 650 | 2 | 9 | 2 | No | 34 |

| 8 | 240 | 600 | 5 | 12 | 1 | No | 35 |

| 9 | 200 | 500 | 1 | 9 | 2 | No | 30 |

| 10 | 190 | 450 | 1 | 28 | 2 | Burst abdomen | 32 |

| 11 | 250 | 600 | 1 | 9 | 3 | SSSI | 37 |

| 12 | 240 | 550 | 1 | 8 | 2 | SSSI | 48 |

| 13 | 260 | 400 | 1 | 7 | 3 | No | 25 |

| 14 | 240 | 500 | 1 | 8 | 2 | No | 21 |

| 15 | 250 | 500 | 1 | 8 | 2 | No | 30 |

| 16 | 280 | 800 | 4 | Died | 2 | No | Expired |

EBL estimated blood loss, BT blood units transfused, CRS cytoreductive surgery and ChT chemotherapy

Table 4 depicts the intraoperative disease burden at the beginning of the procedure and the disease left after completion of surgery. In 12 cases (75%), complete cytoreduction score (CC) CC0 was achieved, three cases CC1 and, in only one case, CC2 was achieved. The cases where CC0 could not be achieved had a peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) score of more than 20. The case where CC2 was achieved had a PCI score of 32. The median SCS (surgical complexity score) was 6 (range: 5–8). In all nine cases, where either Type 1 modified or Type 2 was performed had bowel infiltration of the cancer cells which was confirmed by histopathology.

Table 4.

Intraoperative details

| Case no. | Type of radical oophorectomy | PCI | CC | SCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type 1 modified | 20 | 1 | 8 |

| 2 | Type 1 modified | 13 | 0 | 6 |

| 3 | Type 2 | 24 | 1 | 6 |

| 4 | Type 1 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 5 | Type 1 | 12 | 0 | 5 |

| 6 | Type 2 | 32 | 2 | 8 |

| 7 | Type 1 modified | 20 | 0 | 5 |

| 8 | Type 2 | 21 | 1 | 6 |

| 9 | Type 1 | 8 | 0 | 6 |

| 10 | Type 1 | 8 | 0 | 5 |

| 11 | Type 1 modified | 14 | 0 | 6 |

| 12 | Type 1 modified | 13 | 0 | 6 |

| 13 | Type 1 | 7 | 0 | 6 |

| 14 | Type 1 modified | 15 | 0 | 8 |

| 15 | Type 1 | 11 | 0 | 6 |

| 16 | Type 1 modified | 12 | 0 | 8 |

PCI peritoneal carcinomatosis index, CC completeness of cytoreduction and SCS surgical complexity score

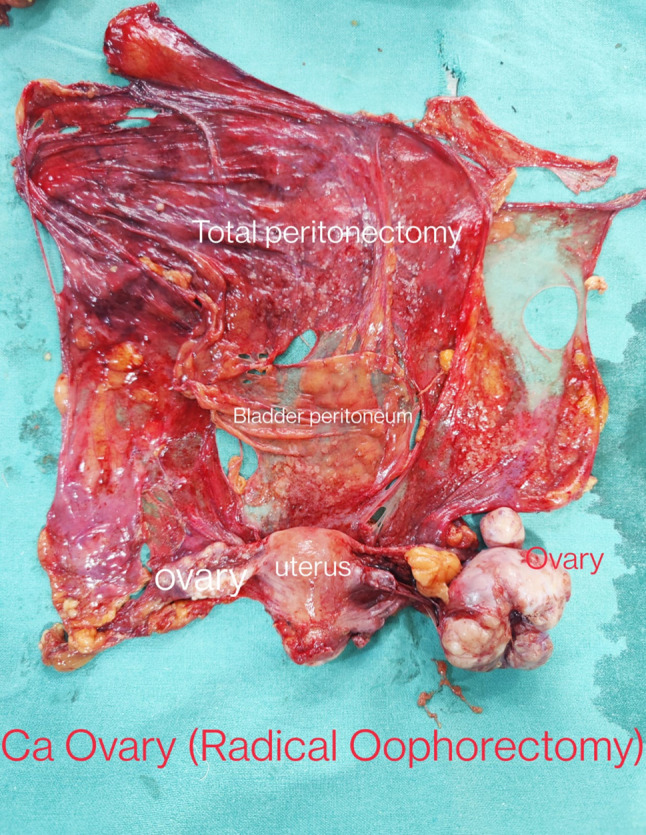

Figure 2 shows a postoperative picture of a Type 1 radical oophorectomy specimen. [Total abdominal hysterectomy with total peritonectomy and en bloc retrieval of the radical oophorectomy specimen has been done.]

Fig. 2.

Image showing postoperative specimen of Type 1 radical oophorectomy (case of advanced CA ovary with extensive disease, enbloc retrieval done)

Discussion

In advanced EOC, tumour dissemination to the peritoneal surfaces of the bladder and bowel is common. En bloc pelvic resections, with or without rectosigmoid colectomy, might be beneficial for patients given the patterns of EOC dissemination and potential remnants of microscopic disease that may not be visible intraoperatively. In our institute, 16 cases of radical oophorectomy where there was extensive disease with the obliteration of cul-de-sac and involvement of bowel peritoneal surfaces have been performed. The cases where there was only superficial rectosigmoid involvement upto ≤ 2 cm, Type 1 modified radical oophorectomy was performed instead of Type 2 radical oophorectomy hence avoiding rectosigmoid colon resection and anastomosis. By this type of modification, the morbidity associated with bowel resection was avoided.

The most common type of radical oophorectomy in our study was Type I modified unlike Kim et al. [9] where they had reported Type 2 radical oophorectomy to be the most common type: Type 1 (18%), Type 2 (74%) and Type 3 (8%).

We were able to achieve CC0 in 75% of cases with radical oophorectomy even with the presence of extensive disease in the pelvis. The four cases where CC0 could not be achieved had a PCI score of more than 20. Except 1 case of burst abdomen, there were only minor complications observed in our study. Minor complications were those that did not require readmission or have an effect on the patient's clinical course. [Clavien–Dindo Grading of complications] The patient's poor nutritional status could be the cause of burst abdomen in our study. Prior to surgery, we usually check the serum albumin levels; however, it was not helpful to detect the patient's poor nutritional condition preoperatively. There were no surgery-related deaths, but one patient succumbed to pulmonary embolism 5 days after the operation. During her hospital stay, she got combined pharmacologic and mechanical venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylactic treatment. Since she was obese, with a BMI of 32.4 kg/m2, which is a risk factor for VTE, the appraisal of the outlined surgical treatment should not be impacted by her death 0.8 patients who underwent interval debulking surgery received 3 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy, while the seven patients who underwent primary cytoreductive surgery each received 6 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin. It took 35 days from surgery to the beginning of chemotherapy, which is comparable to the standard time frame of 4–5 weeks noted in the literature [12, 13]. During the period of our monitoring, there was no recurrence in any of our patients who had been optimally debulked. Fourteen months (a range of 6–28 months) after surgery was the median follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) intervals described in the literature range from 14 to 18 months [14]; therefore, we think that radical oophorectomy in situations when the POD is obliterated could potentially result in a longer PFS.

Besides this, the described method can also be used in other conditions like adnexal mass with obliterated Pouch of Doughlas (POD), grade IV endometriosis, endometriomas, previous history of multiple surgeries where there is the presence of dense adhesions around the uterus and the usual surgical approach is impossible [15]. Besides malignancy even in cases of distorted anatomy of the pelvis encountered during surgery, this approach will prove to be beneficial. The precise oncological advantage of the proposed strategy must be evaluated in prospective clinical trials with a control group.

Conclusion

In today's era, the resection of ovarian cancer (OC) from the pelvis is built on the tenets of Hudson's method.

The present study optimal cytoreduction (residual disease < 1 cm) was obtained in 93.75% cases (15/16 cases). Although three patients had Clavien–Dindo grade 3 complications (two cases of SSSI and one case of burst abdomen), there were no any complications specifically related to this procedure. This method enabled complete clearance of pelvic disease with minimal morbidity. Hence, radical oophorectomy proves to be an effective, feasible and secure surgical technique in cases of advanced ovarian malignancies with extensive involvement of peritoneum, pelvis and visceras.

Funding

No funding received.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the Institutional Ethics Committee of in view of the retrospective nature of the study, and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Dr. Sony Nanda has completed her MCH Gynaecologic Oncology from Acharya Harihar Post Graduate Institute of Cancer in 2023. Currently she is posted as an Assistant Professor at JK Medical College & Hospital. Dr. Manoranjan Mahapatra is an Associate Professor. Dr. Janmejaya Mohapatra is an associate Professor. Dr. Ashok Padhy is an assistant Professor. Dr. Bhagyalaxmi Nayak is a Professor. Dr. Jita Parija is a Professor.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tate S, Nishikimi K, Matsuoka A, et al. Introduction of rectosigmoid colectomy improves survival outcomes in early-stage ovarian cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26(5):986–994. doi: 10.1007/s10147-021-01864-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcazar JL, Jurado M, Minguez JA, et al. En-bloc rectosigmoid and mesorectum resection as part of pelvic cytoreductive surgery in advanced ovarian cancer. J Turk German Gynecol Assoc. 2020;21(3):156. doi: 10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2019.2019.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall M, Savvatis K, Nixon K, et al. Maximal-effort cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer patients with a high tumor burden: variations in practice and impact on outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(9):2943–2951. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07516-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghisoni E, Katsaros D, Maggiorotto F, et al. A predictive score for optimal cytoreduction at interval debulking surgery in epithelial ovarian cancer: a two-centers experience. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0415-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas QD, Boussere A, Classe JM, et al. Optimal timing of interval debulking surgery for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a retrospective study from the ESME national cohort. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;167(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanderpuye VD, Clemenceau JR, Temin S, et al. Assessment of adult women with ovarian masses and treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer: ASCO resource-stratified guideline. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2022;77(2):96–97. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munoz-Zuluaga CA, Sardi A, Sittig M, et al. Critical analysis of Stage IV epithelial ovarian cancer patients after treatment with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy followed by Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC) Int J Surg Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/1467403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erkilinç S, Karataşli V, Demir B, et al. Rectosigmoidectomy and Douglas peritonectomy in the management of Serosal implants in advanced-stage ovarian cancer surgery: survival and surgical outcomes. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28(9):1699–1705. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MS, Noh JJ, Lee YY. En bloc pelvic resection of ovarian cancer with rectosigmoid colectomy: a literature review. Gland Surg. 2021;10(3):1195. doi: 10.21037/gs-19-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shan Y, Jin Y, Li Y, et al. Rectosigmoid sparing en bloc pelvic resection for fixed ovarian tumors: Surgical technique and perioperative and oncologic outcomes. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Somashekhar SP, Ashwin KR, Yethadka R, et al. Impact of extent of parietal peritonectomy on oncological outcome after cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Pleura Perit. 2019 doi: 10.1515/pp-2019-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Zhang G, Peng C, et al. Choosing the right timing for interval debulking surgery and perioperative chemotherapy may improve the prognosis of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a retrospective study. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13048-021-00801-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Zhang T, Wu Q, et al. Relationship between initiation time of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in ovarian cancer patients: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MJ, Vaughan-Shaw P, Vimalachandran D. ACPGBI GI Recovery Group. A systematic review and meta-analysis of baseline risk factors for the development of postoperative ileus in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Ann R Coll Surg England. 2020;102(3):194–203. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecointre L, Gabriele V, Faller E, et al. Laparoscopic En Bloc Pelvic Resection with rectosigmoid resection and anastomosis for stage IIB Ovarian Cancer: Hudson's procedure revisited. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29(9):1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2022.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]