Abstract

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), characterized by fibro or fibrofatty infiltration of the myocardium with a predominant arrhythmic presentation, is a genetically mediated cause of sudden cardiac death in the young and athletic individuals. We report a case of a severe form of biventricular ACM in a middle-aged man with a family history of cardiomyopathy-related young death. The proband was identified to harbor two novel mutations in the DES and DOLK genes and was managed comprehensively with a multidisciplinary team approach. This report reinforces the need for a dedicated cardiovascular genetics program as well as a population-specific genetic database in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is characterized by fibro or fibrofatty infiltration of the myocardium with a predominant arrhythmic presentation. It is a well-recognized genetically mediated cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the young, especially athletic individuals [1,2]. Initially described as a right ventricular morphology (arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, ARVC), the current understanding of the disease has evolved to include biventricular and left ventricular (LV) forms as well [3]. Desmosomal gene mutations are identified in up to 50–60 % of ACM cases, with PKP2 accounting for the majority of cases followed by DSP, DSG2, DSC2 and JUP; non-sarcomeric genes (TMEM43, DES and PLN) account for a minority of cases. Genetic testing has an established role in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of ACM and should ideally be performed in a multidisciplinary cardiogenetic team setting to ensure comprehensive care for the probands and their family members.

There is a significant overlap between ACM and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), both in the phenotype and the genetic underpinnings. Moreover, the desmoplakin (DSP) gene that is implicated in both forms of cardiomyopathy has recently been recognized to cause a distinct clinical entity known as desmoplakin cardiomyopathy characterized by high arrhythmic burden, variable degrees of left ventricular enlargement, late gadolinium enhancement with subepicaridal distribution and episodes of myocarditis-like picture [4]. We report a case of symptomatic biventricular ACM with two novel genetic mutations, managed comprehensively by a multidisciplinary team of cardiologists, electrophysiologist, genetic counselor and clinical geneticist.

2. Case report

A 42-year old male with a recent history of left-sided hemiparesis was referred for cardiovascular evaluation due to suspicion of cardioembolic stroke. His resting electrocardiogram (ECG) showed depolarization and repolarization abnormalities in the form of low-voltage QRS complexes, intraventricular conduction delay and global T-wave inversion. His echocardiography revealed an organized left ventricle (LV) apical clot with global hypokinesia of the LV and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 40 %. Echocardiography also revealed a dilated right atrium (RA) and right ventricle (RV), with severe right ventricular dysfunction and right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) of 35 %. His cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging confirmed biventricular dysfunction and showed dilated RV with dyskinesis and patchy transmural late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in RV anterior free wall, and confluent midmyocardial LGE in the LV basal septum and RV outflow tract septum. His coronary angiogram was normal. The findings were consistent with right ventricular cardiomyopathy with LV involvement (Fig. 1). Small adherent non-enhancing thrombi were seen in the RV and LV apex.

Fig. 1.

Baseline evaluation of the patient.

Panel A: resting ECG with depolarization and repolarization abnormalities in the form of low-voltage QRS complexes, intraventricular conduction delay and global T-wave inversion; Panel B: ECG showing ventricular tachycardia; Panel C: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the coronal section showing dilated RV with dyskinesis and transmural late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in the RV anterior free wall (*) and patchy and confluent LGE in interventricular septum.

The patient did not have any history of syncope, pre-syncope or palpitations prior to the acute stroke. He was born of consanguineous marriage and had been well prior to the stroke (Fig. 2). He was married and had a daughter and son aged 10 years and 2 years respectively. He was employed in a company; his work did not involve manual labor and he was not an athletic individual. His younger brother and only sibling, diagnosed with cardiomyopathy in his early 20's, had died at the age of 25 years in a road traffic accident while driving, suggestive of arrhythmic sudden cardiac death. Interestingly, their father who was diabetic had also died of a presumed myocardial infarction while driving, at the age of 58 years. Their mother was 64 years of age and healthy. Medical records of the family members were unavailable for review.

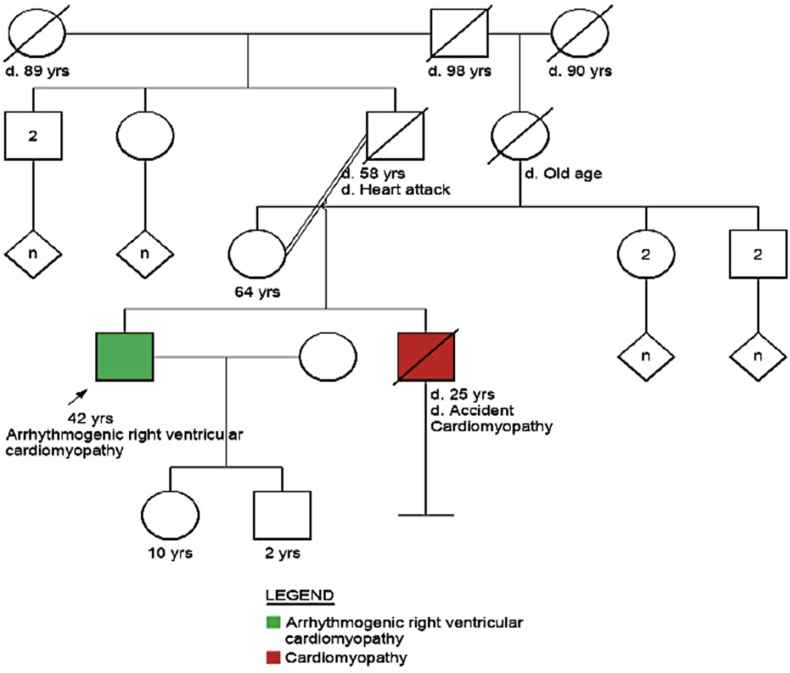

Fig. 2.

Pedigree chart of the patient.

Note death in sibling secondary to cardiomyopathy.

During the cardiac evaluation period, he experienced recurrent episodes of ventricular tachycardia (VT) requiring cardioversion. He was initiated on beta-blocker therapy by the primary cardiologist and referred for further management to our centre. There were more than 2 morphologies of VT noted. As the patient had recurrent episodes of VT despite being on anti-arrhythmic therapy, he was considered for cardiac electrophysiology study (EPS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) procedure. Cardiac EPS revealed an easily inducible tachycardia, whose morphology was the same as the clinical VT. An extensive high density electro-anatomical mapping (EAM) of the RV endocardium and epicardium revealed extensive low voltage zones predominantly in the RV epicardium and extending to the RV endocardium in the RV anterior free wall (Fig. 3). Mapping of the VT also suggested a reentry circuit involving the slow conduction low voltage zones in the RV epicardium. RFA was performed both in the RV anterior free wall in the RV epicardium and the RV endocardium. Fig. 4 shows the entrainment of the VT from the RV epicardium during VT1 and VT2. Both the sites of entrainment were the same region of the epicardium, thus suggesting a shared isthmus for both the VT circuits. RFA was performed at the sites of isthmus on the RV epicardium. Further substrate modification was also performed on the RV endocardium. At the end of the study, no further VT was inducible. A dual-chamber implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was implanted. As the patient had preexisting LV dysfunction, he was intolerant to optimal doses of beta-blockers. Hence, additional atrial lead was provided so as to achieve the optimal dose of beta blockade without causing RV pacing induced worsening of ejection fraction.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac electrophysiology study (EPS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) procedure.

Panel A: fluoroscopy of endo-epicardial mapping performed in the patient; Panel B: color-coded bipolar voltage electro-anatomical map of the RV endocardium. Note the low bipolar voltage zones in the RV anterior free wall; Panel C: color-coded bipolar voltage electro-anatomical map of the RV epicardium. Note the extensive low bipolar voltage in the RV epicardium; Panel D: radiofrequency ablation points in the epicardium (grey shell) and endocardium (green shell); Panel E: electro-anatomical signals in the RV epicardium during ventricular tachycardia. Note the fractionated signals spanning the duration of diastole; Panel F: fluoroscopic picture of the dual chamber ICD implanted in the patient.

Fig. 4.

Entrainment of VT during EPS

Panel A shows the entrainment of VT1 from the RV epicardium resulted in concealed fusion with Stim-QRS/VT CL ratio of 35 %. Panel B shows the entrainment of VT2 from the RV epicardium at the same site resulting in concealed fusion with Stim-QRS/VT CL ratio of 52 %, thus suggesting a shared isthmus for both the VT circuits.

The patient was provided pre-test genetic counseling and genetic testing was done using a targeted cardiomyopathy gene panel using next generation sequencing (NGS). He was identified to harbor two novel mutations of uncertain significance: an autosomal dominantly inherited heterozygous missense variant (c.4513G > A) in exon 23 of the DSP (desmoplakin) gene and an autosomal recessively inherited homozygous mutation (c.1277G > A) in exon 1 of the DOLK (dolichol kinase) gene. While the former is a missense mutation implicated in ACM, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and more recently in desmoplakin cardiomyopathy, the latter is also a missense mutation associated with congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG), which often affects the heart in the form of DCM. The amino acid change p.Cys426Tyr in the DOLK gene is predicted to be conserved by GERP++ and PhyloP across 100 vertebrates. Correspondingly, SIFT analysis predicts the variant to be damaging.

During the post-test counseling, he was explained about the implications of the genetic findings, the importance of follow-up for possible variant reclassification and the need for clinical screening of his children. Eight months since the procedure, the patient is on beta-blockers and oral anticoagulation therapy and has had no further VT episodes or device shocks. On account of worsening heart failure symptoms, the patient has been listed for heart transplantation.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing a severe form of ACM in a middle-aged man harboring double mutations of DSP and DOLK genes. This report highlights the importance of coordinated multidisciplinary care and collaborative efforts to deliver a comprehensive diagnostic work-up, life-saving therapeutic interventions and appropriate prognostication of individuals presenting with complex inherited cardiomyopathies.

While a definite biventricular ACM phenotype satisfying several major criteria outlined by the Task Force and the Padua groups was established readily, the treatment of the rapidly progressing arrhythmogenicity and the interpretation of the double novel mutations were the challenges faced by the cardiogenetic team. DSP cardiomyopathy, an increasingly recognized form of ACM, affects both ventricles, carries high risk for ventricular arrhythmia and heart failure, and is associated with worse outcomes in the presence of myocardial injury [5]. In the patient reported here, the CMR revealed biventricular myocardial fibrosis and EAM pointed to a predominant RV epicardial arrhythmic substrate. Though this patient did not have evidence of myocardial injury or predominant LV involvement, the case still fits the description of DSP cardiomyopathy.

There have been studies suggesting that additional genetic variants, cardiovascular comorbidities, and non-genetic factors contribute to the penetrance of DSC2, DSG2, DSP, JUP, and PKP2-related ARVC [6]. DOLK-CDG affects the heart but can also involve other body systems. Though patients typically develop signs and symptoms during infancy or early childhood, the clinical presentation and severity may vary among affected individuals. Nearly all individuals with DOLK-CDG develop DCM along with other systemic manifestations. Non-syndromic DOLK-CDG with a predominant presentation of DCM has also been observed in affected individuals.

Noticeably, all variants identified in this patient are variants of uncertain significance (VUS), that is, evidence for pathogenicity for the variant is conflicting as per ACMG variant classification criteria. The DOLK VUS is in homozygous state with a possible phenotype overlap, as reported earlier [7], where a predominant presentation of DCM has been observed in affected individuals with nonsyndromic DOLK-CDG. Additionally, as this variant appears novel on available databases (genomAD) and other gene to gene interactions cannot be ruled out with the currently available information, further familial and/or functional studies may be necessary to understand the significance of this variant. In other words, presence of variants in two different genes causing cardiomyopathy highlights the possibility of a blending phenotype explaining the unexpected clinical features such as late onset cardiomyopathy as well as the intriguing family history. Presence of the same variant in multiple affected members can help understand the significance of the variant in that family and also address the concern for early surveillance. Cascade screening has been recommended for the proband's children with clinical evaluation followed by imaging and genetic studies as warranted.

The lack of a population specific genetic database and the dearth of literature pertaining to ACM in India together contribute to the paucity of knowledge of this condition in our patients. Sparing a few reports of ARVC [8,9], one of them highlighting the presenting symptom of stroke in a young adult male and another attempting to unravel the genetic etiology in three ARVC families in the pre-NGS era, there are no systematic studies on the genotype-phenotype correlations in this interesting subset of inherited cardiomyopathies in the Indian population.

The authors would like to highlight that with the recent launch of their dedicated cardiovascular genetics program [10], a concept still unique to a developing country like India, it has been possible to provide an integrated and comprehensive diagnostic, therapeutic and preventive care for this patient. In the authors’ opinion, the rapid advances in the field of genetics and genomics in the last decade has lead to the emergence of reliable and cost-effective genetic testing services in India. It is however the responsibility of the healthcare professionals involved in the cardiogenetic team to perform adequate phenotyping and pre-test genetic counseling prior to submitting the patients for genetic testing and to provide post-test genetic counseling once the genetic test result becomes available. A multidisciplinary team discussion with the patients and their family members to explain the implications of the findings of the genetic test and its impact on the prognostic and therapeutic aspects is an important step. This systematic approach to all familial cardiovascular conditions will result in a better understanding of the genetic underpinnings in our population and help minimize uncertainty in interpreting genetic variations in the future.

In conclusion, we report a case of a severe form of biventricular ACM managed comprehensively with a multidisciplinary team approach. The presence of two novel mutations of uncertain significance reinforces the need for a population-specific genetic database that may enable more accurate interpretation as well as application in the cascade screening process.

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the genetic testing and interpretation support rendered by Neuberg Centre for Genomic Medicine.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Indian Heart Rhythm Society.

References

- 1.Krahn A.D., Wilde A.A.M., Calkins H., et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. JACC (J Am Coll Cardiol): Clinical Electrophysiol. 2022;8:533–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilde A.A.M., Semsarian C., Marquez M.F., et al. Expert Consensus Statement on the state of genetic testing for cardiac diseases. EP Europace. 2022;24:1307–1367. doi: 10.1093/europace/euac030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graziano F., Zorzi A., Cipriani A., et al. The 2020 "Padua criteria" for diagnosis and phenotype characterization of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in clinical practice. J Clin Med. 2022 Jan 5;11(1):279. doi: 10.3390/jcm11010279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Lorenzo F., Marchionni E., Ferradini V., et al. DSP-related cardiomyopathy as a distinct clinical entity? Emerging evidence from an Italian cohort. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:2490. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W., Murray B., Tichnell C., et al. Clinical characteristics and risk stratification of desmoplakin cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2022;24:268–277. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourfiss M., van Vugt M., Alasiri A.I., et al. Prevalence and disease expression of pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants associated with inherited cardiomyopathies in the general population. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2022;15 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.122.003704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefeber D.J., de Brouwer A.P., Morava E., et al. Autosomal recessive dilated cardiomyopathy due to DOLK mutations results from abnormal dystroglycan O-mannosylation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singhi A.K., Bhargava A., Mukherjee S.S., et al. Role of imaging in the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in presence of congenital heart disease. J Indian Acad Echocardiogr Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;5:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh J.M., Ganeshwala G., Mathew N., Venkitachalam A., Natarajan K.U. Young stroke: an unusual presentation of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Neurol India. 2019;67:1528–1531. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.273639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad F., McNally E.M., Ackerman M.J., et al. Establishment of specialized clinical cardiovascular genetics programs: recognizing the need and meeting standards: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]