Abstract

Ossification of the glenoid is a predictable developmental process in adolescents. However, a lack of knowledge of the variability of this process provides a challenge in discerning between normal adolescent development and shoulder pathology. We presented a case of a 15-year-old male with chronic intermittent right shoulder pain who was diagnosed with a labral tear based on presentation, physical exam, and magnetic resonance arthrogram. He subsequently underwent a diagnostic arthroscopy which revealed no evidence of labral or bony pathology and was instead concluded to have an incomplete ossification of the glenoid. His symptoms were assessed to be related to rotator cuff tendinitis, for which he underwent focused physical therapy which resulted in complete resolution of symptoms at his 1-month postoperative follow-up. Understanding the normal ossification process of the glenoid clinically and through imaging can help physicians recognize normal shoulder development and avoid misinterpretation of findings as pathology in adolescent patients.

Keywords: Shoulder pain, Glenoid ossification, Glenoid fracture, Labral tear, Case report

Introduction

Ossification of the glenoid is a normal developmental process in adolescents that progresses in a predictable sequence [1]. The ossification centers offer insight into what structural changes should be expected in specific locations on the developing glenoid [2]. There is, however, some variability in the development based on sex and age that is important to highlight to assist in diagnosis [1]. Gaining familiarity with this topic is vital as the growing number of adolescents participating in overhead sports will lead to more cases of shoulder pain and injury in this population.

We presented a case of a 15-year-old male with chronic intermittent right shoulder pain who was diagnosed with a labral tear based on clinical history, physical exam, and magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA). The patient subsequently underwent a diagnostic arthroscopy which revealed no evidence of labral or bony pathology and was instead concluded to have an incomplete ossification of the glenoid. Patient consent was obtained to present this case.

The purpose of this case report is to (a) describe the ossification process of the glenoid with its imaging characteristics and (b) discuss the patient's clinical course to help physicians decipher between normal shoulder development and pathology in adolescents with shoulder pain.

Case report

A 15-year-old male presented with progressive right shoulder pain after throwing a baseball 18 months prior. The patient described a diffuse 5/10 intermittent sharp pain that was followed by numbness and tingling. The symptoms improved with rest and ice and subsided. However, the patient re-experienced his symptoms after restarting pitching a baseball, which worsened with long-distance throws. He developed a sharp aching pain in his right anterior shoulder and along his triceps from the elbow to the shoulder. He rated his pain 3/10 at rest on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scale but stated it was 7/10 while pitching. The patient denied any popping, clicking, or catching sensations, subjective shoulder instability, history of shoulder or neck problems, or impairment in daily abilities. Additionally, the patient had no history of anterior or posterior shoulder dislocation or instability. The patient found relief with over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. On exam, he was found to have tenderness in the biceps tendon and abnormal active abduction of the right shoulder. Further, the patient had negative apprehension, cross-arm, impingement, and sulcus tests in the right shoulder. However, he had a positive Hawkins test. The rest of the exam was unremarkable. Anterior-posterior (AP), lateral, axillary and Y-view X-rays were performed and showed no fractures or abnormal findings. (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3) He was subsequently sent to physical therapy for sports performance with the goal to transition into a throwing program. After 3 physical therapy sessions over the span of 2 and a half weeks, the patient reported no change in his pain or functional improvement and was subsequently sent for an MRA.

Fig. 1.

Anterior-posterior X-Ray of right shoulder at initial visit.

Fig. 2.

Y-view X-ray of the right shoulder at initial visit.

Fig. 3.

Axillary view X-ray of the right shoulder at initial visit.

MRA was interpreted as an “anterior inferior labral tear with associated glenoid fracture (osseous Bankart lesion) measuring 1.6 × 0.6 × 0.4 cm. Slight flattening of the posterosuperior humeral head was suggestive of prior impaction fracture (Hill-Sachs deformity)” (Fig. 4). Given the chronic nature of the patient's condition and failure of nonoperative measures, the patient was referred for surgical evaluation. On exam, he was found to have significant instability on shoulder abduction and external rotation with apprehension and pain but was otherwise found to have full range of motion and normal strength. He had a 2+ anterior shift, compared to a 1+ anterior shift on his opposite shoulder with shift-load testing. After a consultation and evaluation, he agreed to surgery in the form of arthroscopic stabilization with possible augmentation of the bony Bankart.

Fig. 4.

Sagittal T2-weighted MRA of the right shoulder shows mild flattening of the posterosuperior humeral head, suggestive of a Hill-Sachs deformity.

Surgical technique

A preoperative interscalene block in addition to general anesthesia was administered. After anesthesia was induced, an exam was performed, which revealed a grade 2+ load and shift. The procedure was done in the lateral decubitus position. A standard posterior incision was made, and a thorough diagnostic arthroscopy was performed. Arthroscopy revealed no evidence of an anterior-inferior labral tear or Bankart fracture and an intact biceps and superior labrum. There was also no evidence of glenohumeral chondral lesions. Based on the benign findings on diagnostic arthroscopy, the patient was diagnosed with incomplete ossification of the glenoid and no additional steps were taken intraoperatively.

Eight days postoperatively, the patient was assessed, and his pain was determined to be related to rotator cuff tendinitis. His shoulder instability was thought to be due to physiologic instability attributed to adolescents. He was subsequently referred to physical therapy and underwent a rotator cuff-focused rehabilitation plan. The patient was seen at 10 days and 4 weeks postoperatively. At his 4-week follow up, the patient did not report any shoulder pain and exhibited 180 degrees of forward shoulder flexion and 170 degrees of shoulder abduction. Further, both Hawkins and Neer impingement signs were negative on exam. The patient was concluded to have full functional and pain recovery at this time.

Discussion

Ossification of the glenoid is a normal developmental process that is divided into 4 stages: Preossification, cartilage anlage, ossification, and fusion. Preossification is characterized by the absence of discernable evidence of cartilage anlage, a primitive material. During the second stage, cartilage anlage is identified with irregular borders and a lack of cortical detail. The development of well-circumscribed borders signals the progression into the ossification stage and the process concludes with fusion across the ossified centers evidenced by bridging. The anterior glenoid rim, coracoid, and superior glenoid rim are the secondary ossification centers of the glenoid and develop at varying times in an adolescent's life [1].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) patterns of pediatric skeletal development of the glenoiddescribed by Kothary et al., focused on “morphology and signal characteristics” to identify and follow the progression of the ossification centers throughout development [3]. Further, Sidharthan et al. found that males on average were found to complete ossification of the coracoid at 13 years, superior rim at 14 years, and the anterior rim at 17 years. Females, on average, were found to complete ossification of the superior glenoid at 11 years, the coracoid at 12 years and the anterior glenoid rim at 13 years [1]. These differing time points can help guide a physician's diagnostic process when determining whether pathology is present or not.

Distinguishing between a secondary glenoid ossification center and an osseous Bankart lesion may prove challenging. Awareness of the presence and typical location of an inferior glenoid ossification center that may remain unfused at mid to late adolescence in boys is crucial [1]. The location of the ossification center in the anterior inferior glenoid extending from 3:00 to 6:00 can help delineate an ossification center from an osseous Bankart defect, which most frequently occurs between 2:30 and 4:20 with the defect pointing towards 3:00 [2] (Fig. 5). However, given the potential of an osseous Bankart defect to occur spanning from the superior glenoid through the inferior glenoid, location alone should be one of many factors taken into consideration to distinguish the two. Findings of acute injury including marrow and soft tissue edema, linear osseous fragment contour with non-sclerotic margins, and joint effusion may assist in detecting a traumatic bony Bankart defect [3]. In contrast, an ossification center should appear smooth with sclerotic borders and may demonstrate a jigsaw configuration [3].

Fig. 5.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRA of the right shoulder demonstrates the ossification center present along the anterior inferior aspect of the glenoid, spanning between 3:00 and 6:00 on the glenoid clockface.

MRA may also assist in distinguishing the 2. Intermediate T1 signal interposed between the labrum and the ossification center is expected given the presence of articular cartilage in this area [4] (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). In the setting of an MRA, gadolinium contrast intensity signal would not be expected to interpose the labrum and ossification center, but it may interpose the labrum and Bankart osseous defect. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution as fibrovascular tissue within a Bankart tear site may prevent contrast from extending into the tear.

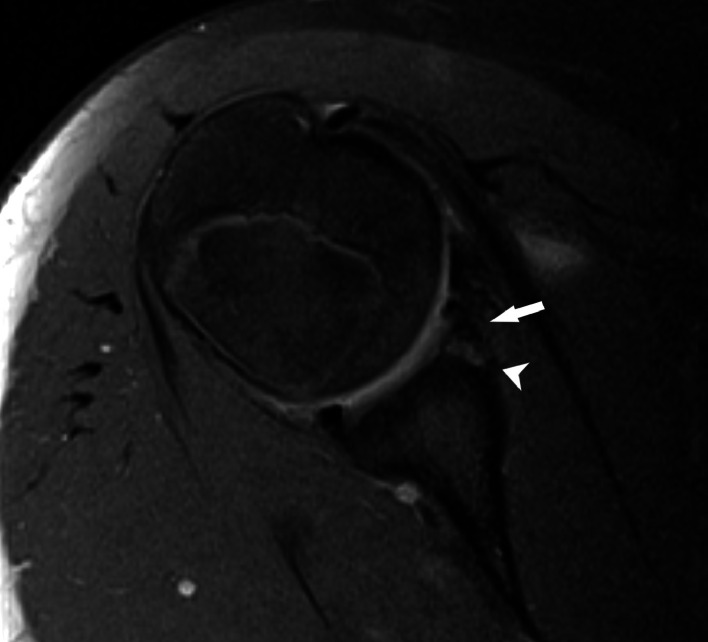

Fig. 6.

T1-weighted MRA of abducted and externally rotated right shoulder showing glenoid secondary ossification center at the anterior inferior aspect of the glenoid with an intact labrum (arrow). Intermediate T1 signal is seen at the border of the secondary ossification signal (arrowhead) representing cartilage.

Fig. 7.

T1-weighted Axial MRA of the right shoulder showing glenoid secondary ossification center at the anterior inferior aspect of the glenoid with an intact labrum (arrow). Intermediate T1 signal is seen at the border of the secondary ossification signal (arrowhead) representing cartilage.

Our patient, a 15-year-old adolescent male underwent an MRA in which the report described an “anterior inferior labral tear with associated glenoid fracture (osseous Bankart lesion)”. Due to their similarity on imaging, incomplete ossification of the anterior rim can be improperly diagnosed as a labral tear in a developing glenoid. MRA is the preferred imaging modality for detecting these lesions as it has a higher sensitivity and specificity for detection. The detachment of the anteroinferior labrum, often with a glenoid rim fracture, can be seen on MRA as a “cleft” of contrast separating the labrum from the glenoid [4,5]. In the 2020 case series by Sidharthan et. al, investigators used 3-dimensional (3D) frequency-selective, fat-suppressed MRI sequences to identify an imaging pattern that could better delineate the stages of glenoid ossification from pathology, such as a Bankart lesion. In addition to MRI, contralateral radiographs can help overcome the individual variability of glenoid ossification as developmental stages may be progressing at a similar rate [2]. However, relying solely on imaging to differentiate pathology from normal development can be a source for misdiagnosis.

Therefore, it is imperative to consider the whole clinical picture, including the history and physical exam. A significant portion of the glenohumeral joint anatomy serves the purpose of ensuring stability. Instances of instability can arise when aspects of the anatomy are compromised such as in glenoid fractures (bony Bankart lesions), humeral head fractures (Hill-Sachs fractures), or labral tears (soft tissue Bankart lesions) [5]. Our adolescent patient's imaging studies were described with the presence of an “anterior inferior labral tear” and “prior impaction fracture (Hill-Sachs deformity)”. Both pathologies, with or without the presence of a labral tears, can be associated with anterior shoulder dislocation [6].

Further, the Hill-Sachs deformity could also be attributed to repeat anterior shoulder subluxations leading to damage to the glenoid labrum. This is especially of concern in “overhead athletes” who participate in sports like baseball, swimming, and tennis, who place an extraordinary amount of stress on the stabilizing anatomy of the glenohumeral joint [7]. Our patient identified a potential inciting event while throwing a baseball, describing the pain to be sharp, intermittent, and diffuse around the right shoulder. Clinically, patients with an injury to the glenoid labrum would resist any movement of the shoulder and physicians would be able to elicit anterior instability with provocative testing on physical exam. Patients with these subluxations would elicit a positive apprehension relocation test by expressing either a sensation of impending dislocation or relief of pain on relocation [6]. Unfortunately, this patient had been through almost a year of conservative measures. This, in combination with the examination and MRI findings, resulted in this patient having a diagnostic arthroscopy.

The increasing number of adolescents who are participating in competitive sports today further underscores the importance of having a strong understanding of the developing shoulder anatomy [8]. Shoulder injuries in pediatric athletes tend to be due to overuse or an acute injury and will only continue to increase in incidence [9]. We aimed to identify the cause of our patient's shoulder pain in a logical and stepwise manner by obtaining the correct diagnostics to arrive at a reasonable diagnosis. However, the lack of immediate recognition of glenoid ossification patterns resulted in the patient undergoing a diagnostic arthroscopy yielding no evidence of structural shoulder pathology.

Ultimately, the similarities between normal adolescent development and shoulder pathology serve as a challenge for orthopedic surgeons. Imaging characteristics of the developing glenoid ossification centers draw a close parallel to those of glenoid fractures and labral tears. Although 3D-MRIs have been shown to identify the subtle differences in ossification and fusion, it is unclear as to whether this can be gleaned on standard MRI and should therefore not solely be relied upon to proceed for operative management [1,8]. Assessing for shoulder instability and apprehension on exam and identifying the clinical history of the pain can provide valuable insight into the potential presence of a true glenoid or labral injury. However, gaining an understanding of the variation in development based on age and sex can help orthopedic surgeons better contextualize shoulder pain in their adolescent patients. We hope this case sheds light on the importance of approaching shoulder pain in adolescent patients in a more nuanced manner to help guide effective clinical management.

Patient consent

Written informed patient consent was obtained for publication of this patient's case for research purposes.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This work was performed at Allegheny General Hospital. The Allegheny Health Network Institutional Review board deemed this study exempt from IRB approval.

Acknowledgments: No funding was involved. There were no proprietary interests in the materials described in the article.

References

- 1.Sidharthan S, Greditzer HG, Heath MR, Suryavanshi JR, Green DW, Fabricant PD. Normal glenoid ossification in pediatric and adolescent shoulders mimics bankart lesions: a magnetic resonance imaging–based study. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(2):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galán-Olleros M, Egea-Gámez RM, Palazón-Quevedo Á, Martínez-Álvarez S, Suárez Traba OM, Pérez ME. Normal ossification of the glenoid mimicking a glenoid fracture in an adolescent patient: a case report. Clin Shoulder Elb. 2023;26(3):306–311. doi: 10.5397/cise.2022.01151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.S K, Zs R, Ll P, S K. Skeletal development of the glenoid and glenoid-coracoid interface in the pediatric population: MRI features. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(9):1281–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00256-014-1936-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The bony bankart lesion: how to measure the glenoid bone loss - PubMed. Accessed September 26, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28243338/.

- 5.Ladd LM, Crews M, Maertz NA. Glenohumeral Joint instability: a review of anatomy, clinical presentation, and imaging. Clin Sports Med. 2021;40(4):585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evaluation of acute traumatic shoulder injury in children and adolescents - UpToDate. Accessed September 26, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-acute-traumatic-shoulder-injury-in-children-and-adolescents.

- 7.Abrams GD, Safran MR. Diagnosis and management of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):311–318. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.070458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Md F. Editorial commentary: Bankart lesion in an adolescent athlete? Not so fast. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(2):345–346. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moyer JE, Brey JM. Shoulder injuries in pediatric athletes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(4):749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]