Abstract

The pulmonary epithelial glycocalyx is rich in glycosaminoglycans such as hyaluronan and heparan sulfate. Despite their presence, the importance of these glycosaminoglycans in bacterial lung infections remains elusive. To address this, we intranasally inoculated mice with Streptococcus pneumoniae in the presence or absence of enzymes targeting pulmonary hyaluronan and heparan sulfate, followed by characterization of subsequent disease pathology, pulmonary inflammation, and lung barrier dysfunction. Enzymatic degradation of hyaluronan and heparan sulfate exacerbated pneumonia in mice, as evidenced by increased disease scores and alveolar neutrophil recruitment. However, targeting epithelial hyaluronan in combination with S. pneumoniae infection further exacerbated systemic disease, indicated by elevated splenic bacterial load and plasma concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines. In contrast, enzymatic cleavage of heparan sulfate resulted in increased bronchoalveolar bacterial burden, lung damage, and pulmonary inflammation in mice infected with S. pneumoniae. Accordingly, heparinase-treated mice also exhibited disrupted lung barrier integrity as evidenced by higher alveolar edema scores and vascular protein leakage into the airways. This finding was corroborated in a human alveolus-on-a-chip platform, confirming that heparinase treatment also disrupts the human lung barrier during S. pneumoniae infection. Notably, enzymatic pretreatment with either hyaluronidase or heparinase also rendered human epithelial cells more sensitive to pneumococci-induced barrier disruption, as determined by transepithelial electrical resistance measurements, consistent with our findings in murine pneumonia. Taken together, these findings demonstrate the importance of intact hyaluronan and heparan sulfate in limiting pneumococci-induced damage, pulmonary inflammation, and epithelial barrier function and integrity.

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia, acute lung injury, glycosaminoglycans, heparan sulfate, hyaluronan

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is associated with high morbidity and mortality despite vaccination and antibiotic use. Streptococcus pneumoniae (S.pn.) is commonly detected as the most frequent bacterial pathogen in patients with CAP (1–3). Disease progression may result in severe CAP, defined by acute respiratory failure and the need for mechanical ventilation (4–6). Acute lung injury is characterized by hypoxemia, enhanced pulmonary vascular permeability, and inflammation-mediated lung injury (7, 8).

One factor involved in acute lung injury that remains incompletely understood is the functional role of the glycocalyx in the context of pulmonary inflammation (9). The glycocalyx is a functional layer of glycoproteins and proteoglycans anchored to the plasma membrane of virtually all cells (10), including lung epithelial cells (11). The proteoglycans are bound to the cell membrane via core proteins containing a transmembrane domain and have long unbranched glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains consisting of polysaccharides with repeating disaccharide units. Among the most common GAGs in the lung glycocalyx are chondroitin sulfate, heparan sulfate, and hyaluronan (12).

Unlike the glycocalyx of the lung epithelium, the role of the endothelial glycocalyx in pulmonary capillaries has been widely studied: It serves as a mechanosensor and signal transducer (13–15); regulates vascular permeability (16, 17); and binds anticoagulant mediators (18), growth factors, and chemokines (19, 20). Although these functions are of elementary importance, many of them are closely linked to vascular blood flow, leaving the functional role of the alveolar epithelial glycocalyx unclear. It has been postulated that it may be involved in maintaining a functioning air–blood barrier and that shed heparan sulfate may serve as a binding target for inhaled pathogens, acting as a decoy receptor (9). A limited number of studies have investigated its role during lung inflammation, demonstrating alveolar heparan sulfate shedding in mice after LPS-induced lung injury, as well as in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. In both cases, GAG shedding was correlated with increased lung permeability (9, 21).

The role of the epithelial glycocalyx during bacterial pneumonia is of particular interest, because pathogenic bacteria produce a variety of virulence factors to modify host carbohydrates and adhesins, which improve host cell attachment (22, 23). In particular, S.pn. produces the virulence factor hyaluronidase (24, 25) and may thus be able to cleave one of the main GAGs of the glycocalyx. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that the pneumococcal exotoxin pneumolysin contributes to shedding of the glycocalyx from alveolar epithelial cells (26).

Collectively, however, the involvement of microbial and host-mediated GAG processing in the orchestration of pulmonary inflammation and disease pathology remains poorly understood. Here, we used intranasal delivery of heparinase and hyaluronidase to degrade two major glycocalyx GAGs during S.pn. infection in a murine model of pneumococcal pneumonia. Some of the results of these studies were previously reported in the form of a preprint (27).

Methods

Mice and Housing

Eight- to 10-week-old specific pathogen–free female C57BL/6J mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions for at least 5 days before experimental treatments. Mice were kept in groups of three or four in individually ventilated cages with a 12-hour/12-hour day/night cycle and had free access to food and water. All experiments were performed in compliance with national and international guidelines for the care and humane use of animals and approved by the relevant state authority, Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, Berlin, Germany (no. G0099/21).

Infection, Monitoring, and Dissection

Animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine-xylazine (93.75 mg/kg of body weight ketamine, 15 mg/kg xylazine of body weight) and infected transnasally in an upright position with a final volume of 20 μl 1× PBS containing 5 × 106 colony-forming units (CFUs) of S.pn. serotype 3 (ST3) with or without addition of either hyaluronidase from bovine testes type I-S (90 units [unit definition provided in Supplementary Methods section of the data supplement] dissolved in 1× PBS) or heparinase I and III blend from Flavobacterium heparinum (15 sigma units [unit definition provided in Supplementary Methods] dissolved in 1× PBS). Control (sham-infected) mice received 20 μl of PBS with or without the addition of enzymes. Corneas were protected under anesthesia by Thilo-Tears Gel (Alcon Deutschland GmbH). Clinical parameters were recorded and behavioral signs of disease scored (see Table E1 in the data supplement) before the start of the experiment and every 12 hours from 24 hours postinfection (hpi). Dissection of the animals was performed at 2 hpi for electron microscopic analysis and at 48 hpi for all other analyses under terminal ketamine-xylazine anesthesia (intraperitoneal injection; 200 mg/kg of body weight ketamine and 20 mg/kg of body weight xylazine), and exsanguination was performed after loss of the intertoe reflex.

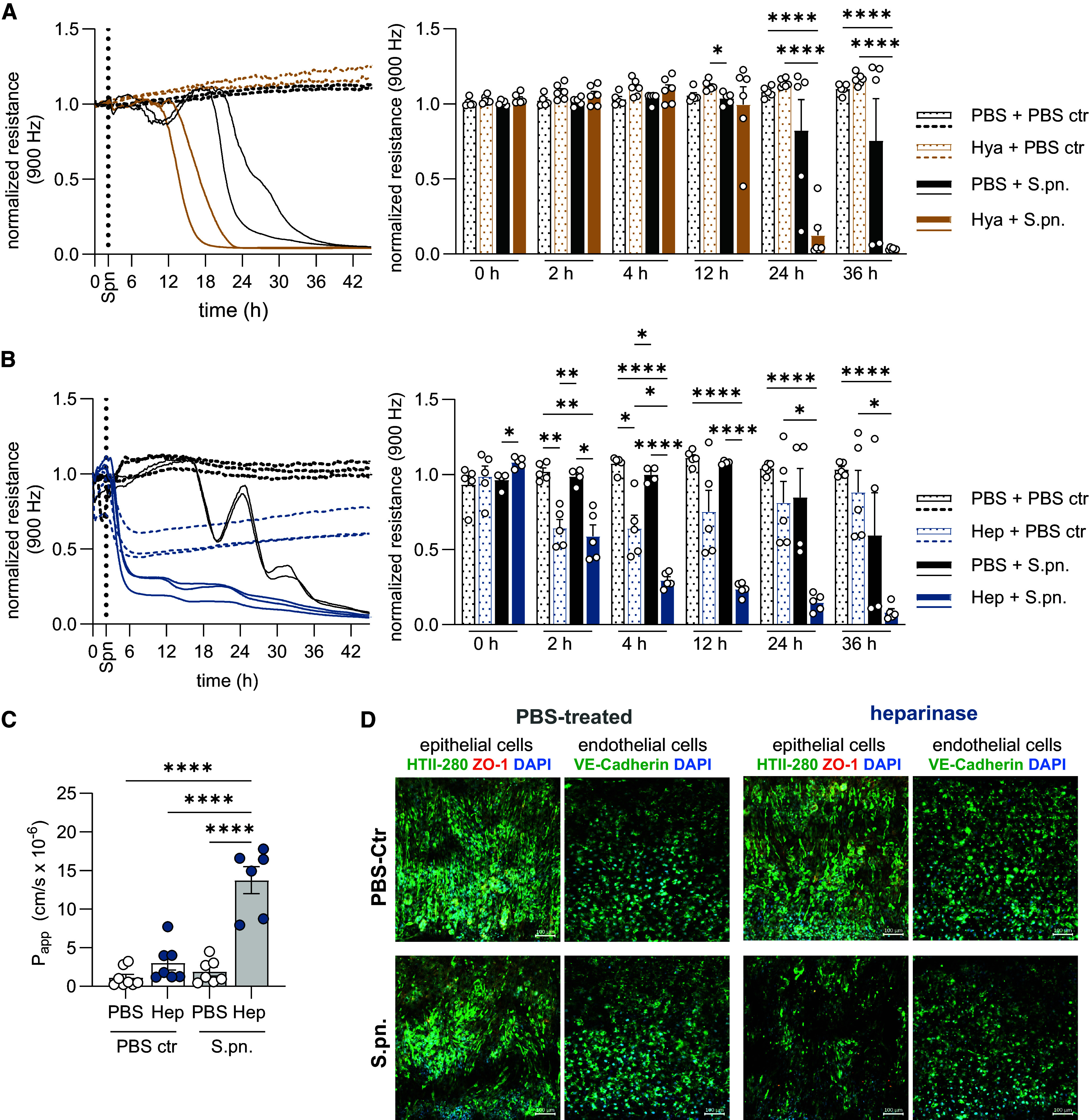

Electric Cell Substrate Impedance Sensing

Electric cell substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) (28) was performed to evaluate changes in barrier properties and viability of human primary alveolar epithelial cells (HPAECs) in monoculture after stimulation with hyaluronidase or heparinase in the presence or absence of S.pn. infection. Transepithelial electrical resistance at low alternating current frequency (900 Hz) was recorded over time.

Human Alveolus-on-a-Chip

HPAECs and human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs) were sequentially seeded on the top and bottom channels of activated and extracellular matrix–coated chips, respectively. Channels were perfused at 60 μl/h with complete human epithelial cell medium for HPAECs and complete EGM-MV2 for HPMECs. Air–liquid interface culture was induced (Day 6 of seeding), and cyclic stretch was applied at 5% strain and 0.2 Hz (Day 10 of seeding). Chips were treated with 500 sigma U/ml final concentration of heparinase I/III or PBS only (Day 15 of seeding). The next day, barrier function was analyzed by applying tracer (Cascade Blue hydrazide) to the bottom channel. After collecting samples for tracer measurement, the cells were fixed for immunofluorescence staining.

Data Analysis

Results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was determined as described in the figure legends. All graphs depict mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All other details are described in the extended Materials and Methods section of the data supplement.

Results

Enzymatic Targeting of Epithelial GAGs Aggravates Pneumococcal Pneumonia

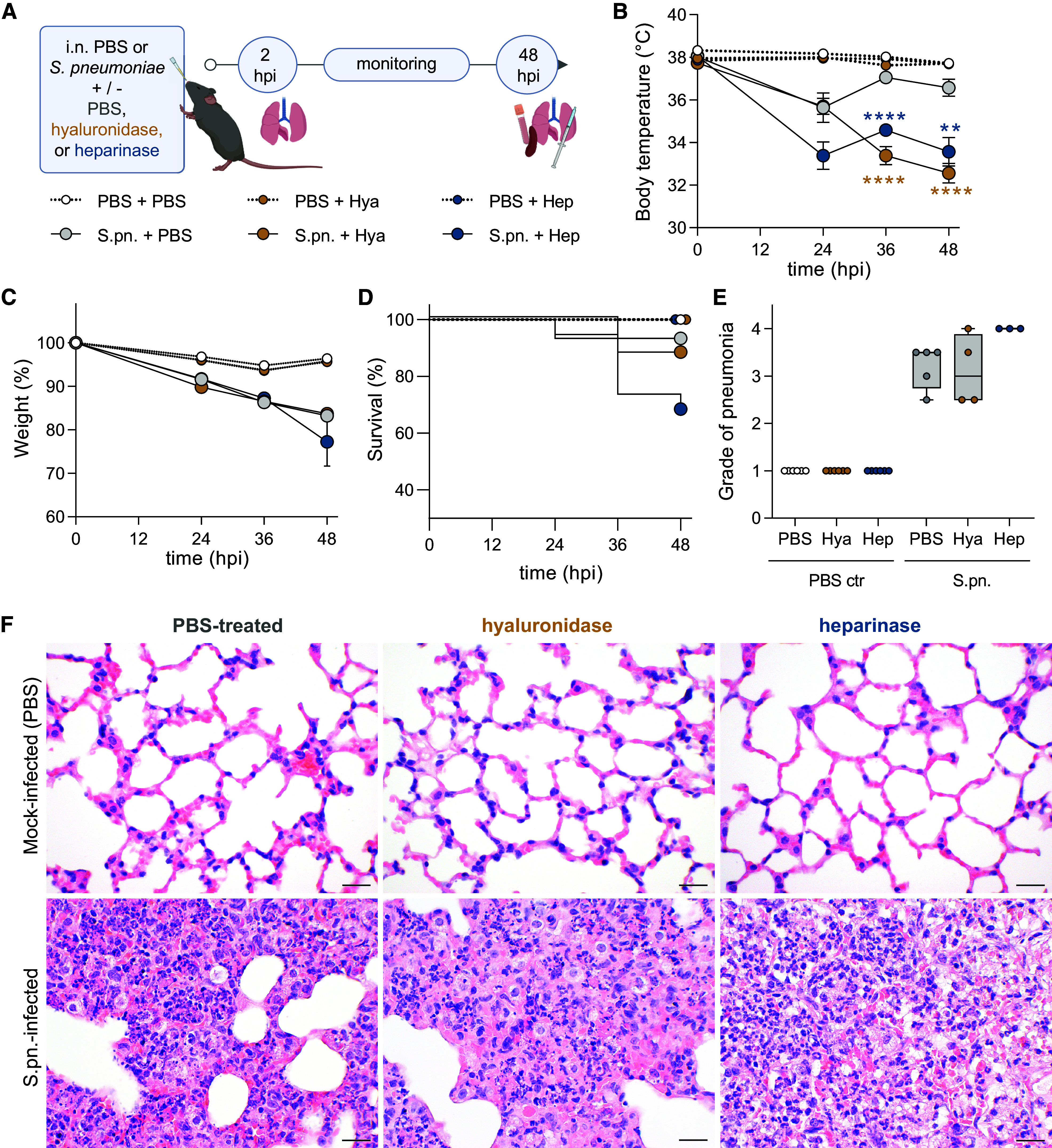

To improve our understanding of epithelial glycocalyx function during bacterial pneumonia, we targeted common glycocalyx GAGs enzymatically with heparinase or hyaluronidase in a murine pneumococcal pneumonia model by adding the enzymes directly to the bacterial inoculum. C57BL/6J mice were transnasally infected with a mixture of S.pn. ST3 and either PBS only (infected-only control) or PBS containing either heparinase (15 sigma units), or hyaluronidase (90 units). Mock-infected control animals received PBS with or without enzymes but without the addition of bacteria. Clinical status was monitored at 24, 36, and 48 hpi, and animals were killed for further analysis at 48 hpi, when pneumonia had developed. In addition, three animals in each group were killed at 2 hpi for electron microscopic imaging (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Enzymatically targeting pulmonary glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) worsens symptoms and severity of pneumococcal pneumonia. Mice were infected intranasally (i.n.) with Streptococcus pneumoniae (S.pn.) or PBS (PBS ctr) with addition of hyaluronidase (Hya) or heparinase (Hep) or PBS as a control and killed at 48 hours postinfection (hpi). (A) Experimental layout. Graphs display (B) body temperature (°C), (C) weight change (%), and (D) survival of experimental animals over the infection course. (B, C) Mixed-effect analysis, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, tested against S.pn. + PBS. Test results displayed for S.pn. groups; n = 14–19 mice per group. **P ≤ 0.01 and ****P ≤ 0.0001. (D) Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test; no significant differences between infected groups. (B–D) Data derived from 17 independent experiments. (E) Histopathological degree of pneumonia ranging from (0) absent to (4) severe at 48 hpi. n = 3–6 mice per group; data derived from six independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparisons tests. Significance was tested between treatments (PBS and enzymes) for sham (PBS ctr) and S.pn.-infected groups. Data are displayed as box plots. Middle line displays median, box indicates first and third quartiles, and whiskers indicate minimum to maximum. (F) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of murine lungs. Although mock infection resulted in almost no lesions across all groups (upper panel), all infected groups developed diffuse alveolar damage with highest severity, density, and damage in heparinase-treated mice (H&E stain). Scale bars, 20 μm.

Clinical monitoring for signs of pneumonia included measurements of body temperature (Figure 1B), weight (Figure 1C), survival (Figure 1D), and behavioral disease score (Figure E1A, Table E1). Unlike mock-infected animals, mice that were infected with S.pn. displayed loss of body temperature and weight over infection time (Figures 1B and 1C). Addition of hyaluronidase or heparinase to the infection inoculum aggravated the disease course: Body temperature loss was significantly more pronounced by 36 hpi, whereas body weight loss remained similar over time in infected mice, independent of treatment (Figures 1B and 1C). At 48 hpi, the disease score of enzyme-treated mice worsened significantly toward inactivity, poorer grooming, and labored breathing (Figure E1A). Accordingly, 6 of 19 and 2 of 16 infected mice from the heparinase and hyaluronidase groups, respectively, had to be killed at humane endpoints set by the regulatory authority before 48 hpi, compared with only 1 of 15 mice from the infected group that received no enzymes; the survival rates between infected mice with enzyme and control treatment, however, were not significantly different by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Figure 1D).

Histopathology scores were discriminative between infected and mock-infected mice. Among the enzymatically treated groups, heparinase-treated mice had the most severe pneumonia scores (Figure 1E, Table E2). All mock-infected mice, including enzyme-only–treated groups, developed almost no histopathological changes (Figure 1F, upper panel). In contrast, infection resulted in mostly moderate, multifocal, purulent bronchoalveolar pneumonia (Figure 1F, lower panel) with diffuse alveolar damage.

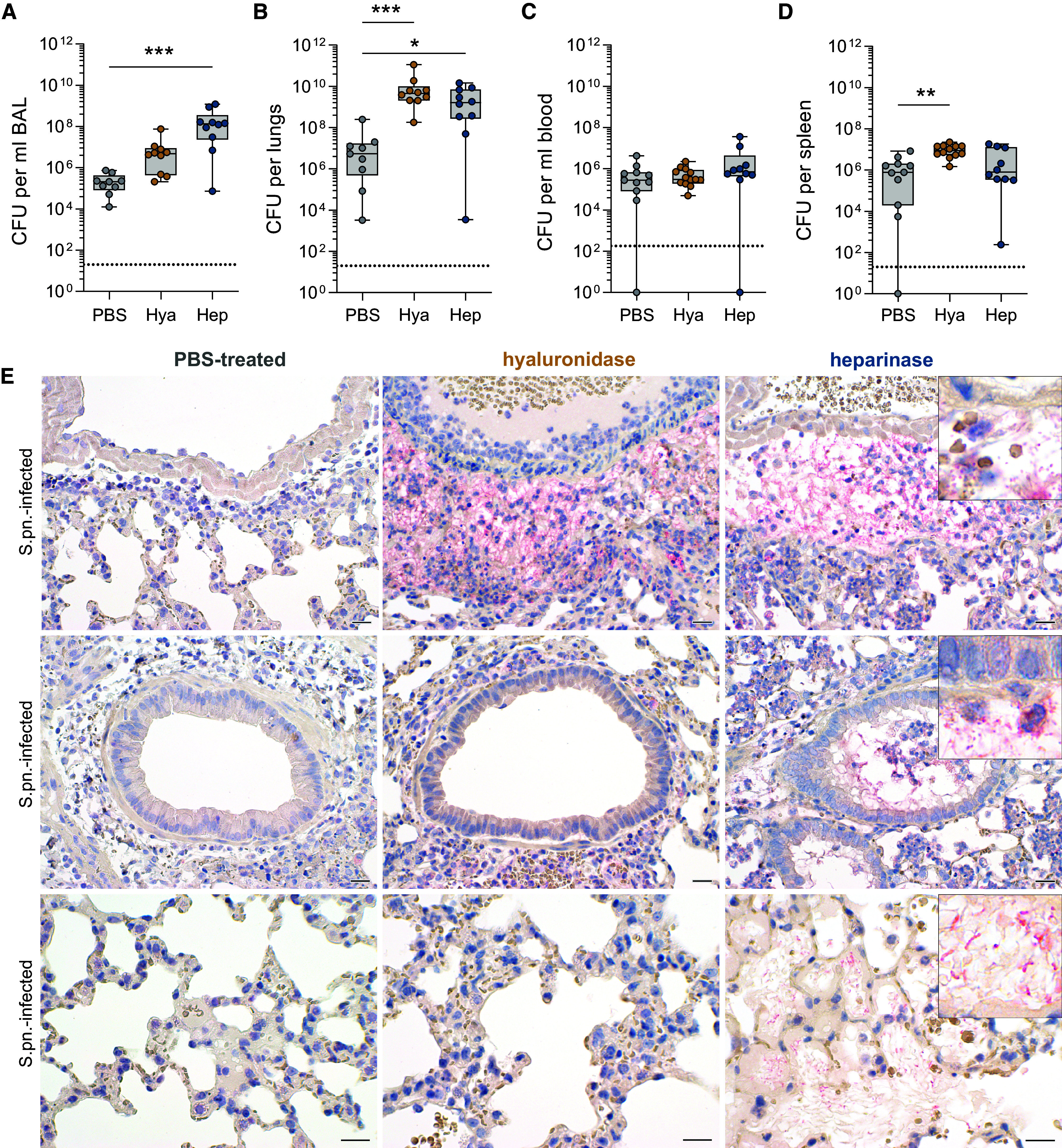

Next, we assessed the bacterial burden and dissemination in S.pn.-infected mice. Hyaluronidase-treated mice displayed a trend for higher bacterial loads in the BAL but exhibited significantly enhanced bacterial burden in lungs, whereas heparinase treatment resulted in significantly elevated bacterial burden in both BAL and lungs compared with the infected PBS-treated group (Figures 2A and 2B). We could not detect any differences in blood bacterial burden among infected groups, whereas only hyaluronidase-treated mice displayed significantly higher bacterial burden in the spleen compared with PBS-treated infected mice (Figures 2C and 2D). To probe whether enzyme treatment directly affected bacterial growth, we grew S.pn. ST3 in Todd Hewitt’s broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract in the presence of heparinase (30 sigma units/ml) or hyaluronidase (180 units/ml) and measured bacterial growth at 600-nm optical density until stationary phase. We observed no difference in growth compared with the control group cultured without enzymes (Figure E1B). In addition, we spread inoculum samples (750 sigma units/ml heparinase, 4,500 units/ml hyaluronidase) on blood agar plates and counted the CFUs after overnight incubation. Again, we observed no difference between samples containing enzymes and controls (Figure E1C). To further assess whether bacteria were using hyaluronic acid, heparin, or their enzymatically cleaved forms as nutrients, we analyzed S.pn. ST3 growth kinetics in chemically defined medium (Table E3) in the presence or absence of hyaluronic acid or heparin with or without hyaluronidase or heparinase, respectively. We observed no differences in bacterial growth kinetics upon supplementation of growth medium with GAGs and associated enzymes (Figure E1D).

Figure 2.

Enzymatic targeting of epithelial glycocalyx alters susceptibility to streptococcal pneumonia. Mice were infected i.n. with S.pn. with addition of Hya or Hep or PBS as a control and killed at 48 hpi. (A–D) Colony-forming units (CFU) for (A) BAL, (B) lungs, (C) blood, and (D) spleen. Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison tests; n = 9–13, data derived from 11 independent experiments, significant differences were tested between treatments (PBS and enzymes) for S.pn.-infected groups. Data are displayed as box plots. Middle line displays median, box indicates first and third quartiles, and whiskers indicate minimum to maximum. Dotted lines indicate the limit of detection (LOD); BAL, 20 CFU/ml; lungs and spleen, 20 CFU/organ; blood, 200 CFU/ml. Samples below LOD were set to 1 or 1/ml. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. (E) Immunohistochemical visualization of S.pn. (New fuchsin, red) in lungs from S.pn-infected and PBS-treated (left panel), hyaluronidase-treated (middle panel), or heparinase-treated (right panel) mice with hematoxylin (blue) as a counterstain. Upper row: perivascular region; middle row: intrabronchiolar region; bottom row, intraalveolar region. n = 3–6 mice per group; data derived from six independent experiments. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Because streptococcal burden in organs pointed toward biased localization between groups, we visualized pulmonary S.pn. by New fuchsin staining (red) and immunohistochemistry. In two out of four PBS-treated mice, bacteria were undetectable by immunohistochemistry throughout the entire lungs. In contrast, all enzyme-treated mice had large amounts of free bacteria in the perivascular spaces. Furthermore, only heparinase-treated mice had numerous free bacteria in intrabronchiolar and intraalveolar spaces (Figures 2E and E1E).

Neutrophil Recruitment and Inflammation Are Enhanced after Enzymatic Targeting of Epithelial GAGs

Immunohistopathology revealed streptococci targeted by professional phagocytes (Figure 2E). We thus quantified the presence of innate immune cells at 48 hpi, using flow cytometric analysis of BAL cells (gating strategy in Figure E2). Significantly increased numbers of CD45+ leukocytes, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocyte-derived inflammatory macrophages were detected in all infected groups compared with uninfected controls. Addition of hyaluronidase and heparinase increased neutrophil numbers further than infection alone. In contrast, recruitment of Ly6Chi inflammatory macrophages remained at PBS treatment level for heparinase-treated mice and was significantly lower in hyaluronidase-treated mice (Figures 3A–3C). Upon infection, neutrophils represented over 70% and Ly6Chi inflammatory macrophages approximately 2–4% of the alveolar leukocytes; the proportion of neutrophils was also significantly enhanced in mock-infected heparinase-treated mice (Figures 3D–3G). We did not detect any significant differences in the numbers of alveolar macrophages in response to enzyme treatment at this stage of infection (Figure E3A), although the overall proportion of alveolar macrophages was reduced in all infected mice, and significantly so in heparinase-treated sham-infected mice (Figures E3B and E3C), likely as a result of neutrophil influx (Figures 3B and 3D). Notably, alveolar concentrations of IL-17A, which is associated with epithelial activation toward neutrophil recruitment, as well as of the neutrophil-chemoattractants CXCL1 and CXCL5, were significantly increased upon heparinase treatment in infected mice (Figures 3H–3J).

Figure 3.

Inflammatory cell recruitment is enhanced after targeting of epithelial glycocalyx in pneumonia. Mice were infected i.n. with S.pn. or PBS (PBS ctr) with addition of Hya or Hep or PBS as a control and killed at 48 hpi. (A–G) Flow cytometry–based analysis of immune cells. Total numbers of (A) CD45+ leukocytes, (B) polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), and (C) Ly6Chi inflammatory monocyte–derived macrophages (Ly6Chi iM) in BAL were determined by use of counting beads, whereas cell frequencies (D–G) were determined as a percentage of CD45+. (E, G) Dot plots representing cellular frequencies among CD45+ leukocytes. (H–J) Protein concentrations of IL-17A (LOD, 4.42 pg/ml), CXCL5, and CXCL1 in BAL fluid (BALF) as quantified by ELISA. Dotted lines indicate LOD. Values below LOD were set to half LOD for statistical analysis. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 8–10; data derived from 11 independent experiments. Significant differences were tested between treatments (PBS and enzymes) for sham (PBS ctr) and S.pn.-infected groups. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

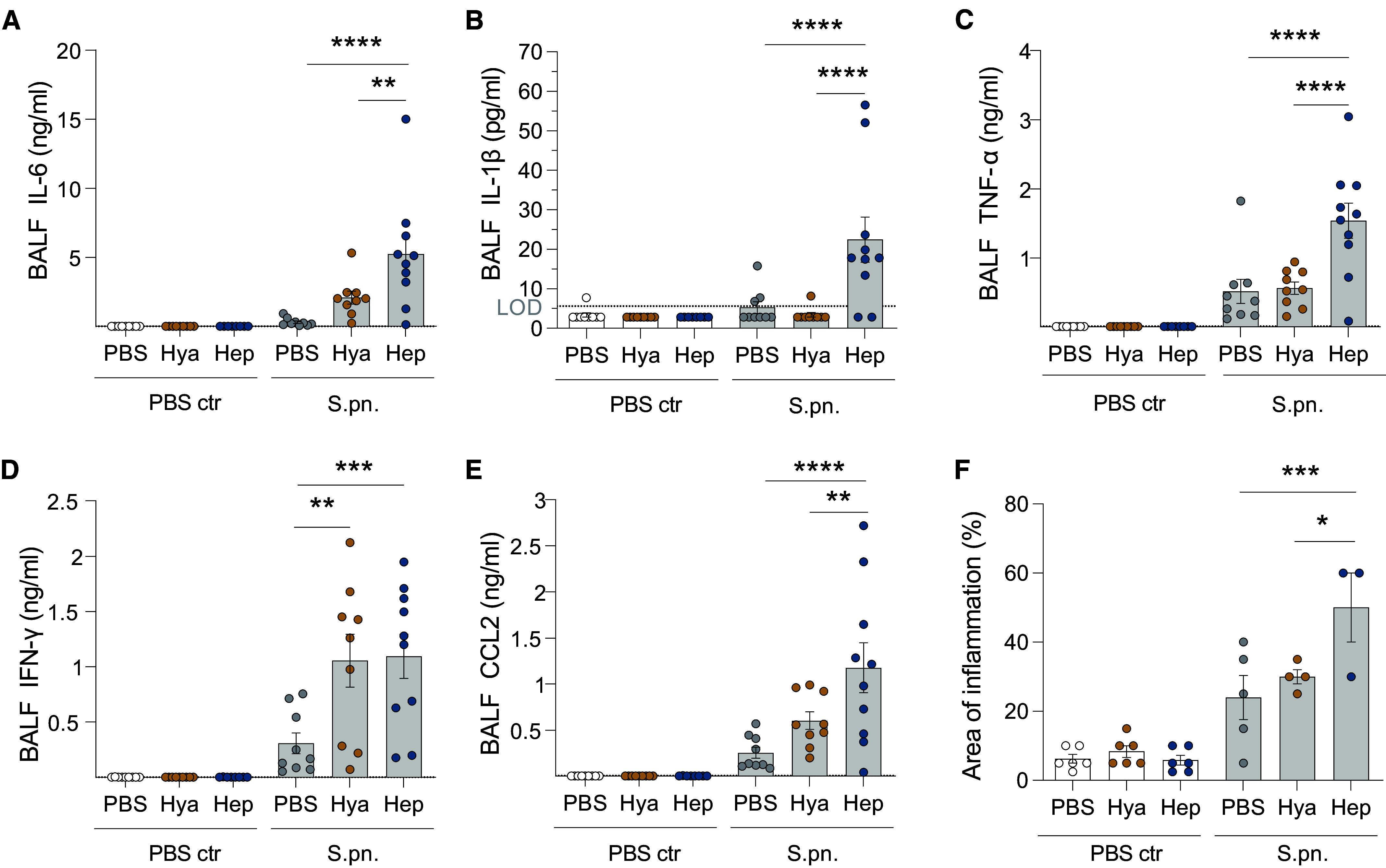

To gain more comprehensive insight into effects on inflammatory mediators known to play a role in pneumococcal infection, we quantified the concentrations of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and CCL2. Without infection, we observed no increase in BAL fluid (BALF) concentrations of any of these factors in response to enzyme treatment. Heparinase treatment of S.pn.-infected animals resulted in significantly elevated BALF concentrations of the examined inflammatory cytokines compared with infection-only or hyaluronidase-treated animals (Figures 4A–4E). In line with this, histopathological evaluation found larger areas of inflammation in infected heparinase-treated animals (Figures 1F and 4F). Treatment with hyaluronidase caused no or only nonsignificant increases in cytokine concentrations over infection alone, except for BALF IFN-γ (Figure 4D). Cytokine concentrations in plasma were only mildly elevated upon infection for IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and CCL2. Enzymatic treatment further elevated the concentrations, with significant increases found for plasma concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and CCL2 upon hyaluronidase treatment (Figures E4A–E4E).

Figure 4.

Targeting of epithelial glycocalyx enhances release of proinflammatory mediators. Mice were infected i.n. with S.pn. or PBS (PBS ctr) with addition of Hya or Hep or PBS as a control and killed at 48 hpi. The concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokine CCL2 in BALF were measured by multiplex ELISA: (A) IL-6 (LOD, 1.72 pg/ml), (B) IL-1β (LOD, 5.66 pg/ml), (C) TNF-α (LOD, 13.49 pg/ml), (D) IFN-γ (LOD, 1.06 pg/ml), and (E) CCL2 (LOD, 5.54 pg/ml). Dotted lines indicate LOD. Values below LOD were set to half LOD for statistical analysis. (F) Area of inflammation detected during histopathological examination of H&E-stained lung tissue. (A–F) Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, control group versus treated groups. (A–E) n = 8–10; data derived from 11 independent experiments. (F) n = 3–6; data derived from six independent experiments. (A–F) Significant differences were tested between treatments (PBS and enzymes) for sham (PBS ctr) and S.pn.-infected groups. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

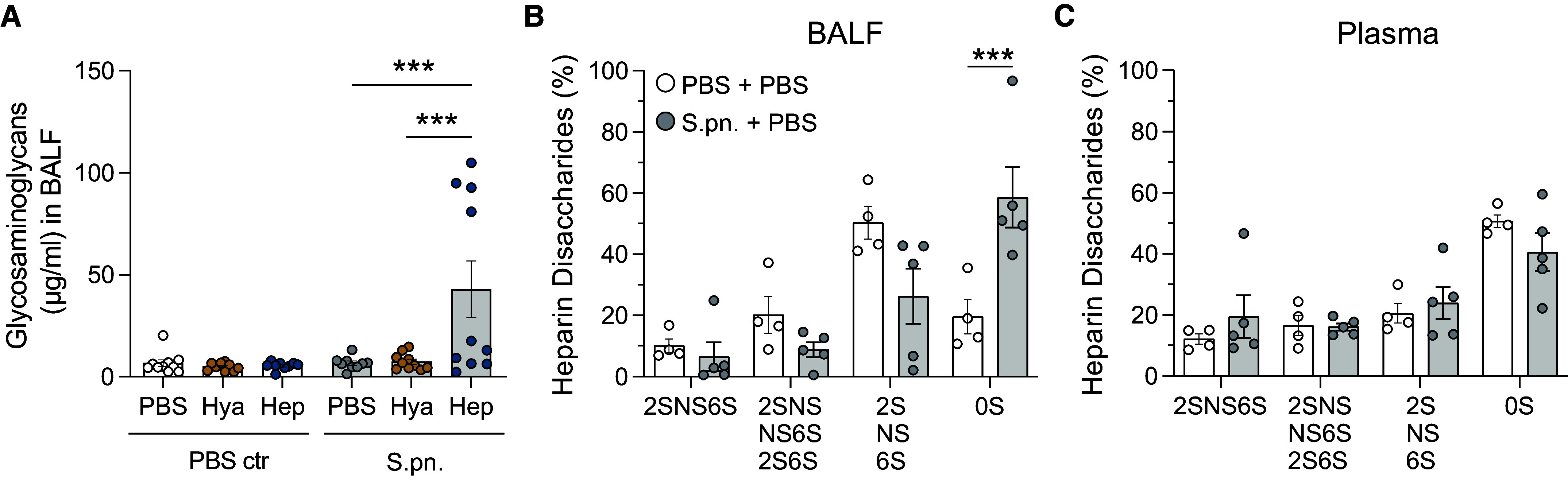

Streptococcal Pneumonia Mediates Glycocalyx Shedding and Alters the Sulfation Pattern of Shed Heparan Sulfate

To test how enzymatic targeting of heparan sulfate or hyaluronan GAGs of the glycocalyx affected subsequent GAG shedding, we used the 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue assay to determine the concentration of sulfated GAGs in BALF at 48 hpi. Enzymatic treatment or infection alone did not elevate concentrations above the low concentrations observed in PBS-only controls, whereas heparinase treatment in combination with infection led to a significant increase in the GAG concentration present in BALF (Figure 5A). Although increased GAG shedding into BALF could be quantified during S.pn. infection in combination with heparinase treatment at 48 hpi (Figure 5A), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining of murine lungs at 48 hpi did not reveal any pattern of enzyme- or infection-mediated signal loss along alveolar epithelial cell surfaces (Figure E5A). In a qualitative assessment of vascular endothelial cells, however, WGA signal was strongly reduced during S.pn. infection relative to PBS-infected mice, regardless of PBS or enzymatic treatment (Figure E5B). To further test whether enzyme exposure in the absence of infection results in shedding of GAGs, we performed a 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue assay, which revealed no differences in plasma GAG concentrations in the presence or absence of hyaluronidase or heparinase (Figure E6).

Figure 5.

Heparin disaccharides are shed and remodeled during pneumococcal infection and after heparinase treatment in mice. Mice were infected i.n. with S.pn. or PBS (PBS ctr) with addition of Hya or Hep or PBS as a control and killed at 48 hpi. (A) GAG shedding into BALF was determined by dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 9–10, data derived from 11 independent experiments. Significant differences were tested between treatments (PBS and enzymes) for sham (PBS ctr) and S.pn.-infected groups. High-performance liquid chromatography was performed on pooled (B) BALF and (C) plasma samples to analyze sulfation of heparin disaccharides. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 4–5 (pooled from two or three independent samples derived from 11 independent experiments). Significant differences were tested between sham (PBS + PBS) and S.pn.-infected (S.pn. + PBS) groups. HexA-GlcNAc = 0S, HexA(2S)-GlcNAc = 2S, HexA-GlcNS = NS, HexA-GlcNAc(6S) = 6S, HexA(2S)-GlcNAc(6S) = 2S6S, HexA(2S)-GlcNS = 2SNS, HexA-GlcNS(6S) = NS6S, HexA(2S)-GlcNS(6S) = 2SNS6S. ***P ≤ 0.001.

To detect changes in the sulfation status of shed heparan sulfate, we determined the proportions of different disaccharides using high-performance liquid chromatography of full-length heparan sulfate derived from BALF (Figure 5B) and plasma (Figure 5C). Infection led to a marked increase in unsulfated (0S) heparin disaccharides detected in BALF (Figure 5B), whereas monosulfated (2S, NS, 6S), disulfated (2SNS, NS6S, 2S6S), or trisulfated (2SNS6S) heparin disaccharide fractions remained similar between infected and sham groups. By contrast, in plasma, the proportions of heparin disaccharide fractions did not change significantly between infected and sham groups (Figure 5C). It should be noted that small GAG fragments already present in the BALF, such as those generated by hyaluronidase and heparinase activity, are currently not detectable because of methodical limitations. For these reasons, we restricted the analysis to groups without prior enzyme treatment.

Disruption of Epithelial Glycocalyx Aggravates Infection-triggered Damage of the Epithelial Lung Barrier

Next, we examined how enzymatic glycocalyx modulation affected lung barrier permeability to macromolecules, because severe pneumonia is characterized by breakdown of the air–blood barrier. At 48 hpi, BALF from infected animals contained elevated concentrations of protein, which were significantly higher in the heparinase group. Indeed, even in the noninfected animals, heparinase caused a small, insignificant increase in protein concentrations compared with PBS only (Figure 6A). As expected, perivascular edema was minimal in all noninfected groups but moderate to high in the infected groups (Figure 6B). In addition, the infected groups also showed low- to moderate-grade alveolar edema (Figure 6C). Fluid accumulation in the adventitia was accompanied by extravasation of neutrophils and erythrocytic leakage into the perivascular space (Figure 6D, upper panel). Notably, alveolar edema and alveolar hemorrhage were most pronounced in the heparinase-treated mice (Figure 6D, lower panel). Taken together, combination of S.pn. infection with heparinase treatment led to the most severe edema, inflammation, and tissue damage when compared with the other groups. In addition, only heparinase treatment in combination with S.pn. infection resulted in intraalveolar hemorrhage (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Lung barrier function is impaired by enzymatic glycocalyx modulation during pneumococcal pneumonia. Mice were infected i.n. with S.pn. or PBS (PBS ctr) with addition of Hya or Hep or PBS as a control and killed at 48 hpi. (A) Protein content in BALF was determined by colorimetric assay. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 9–10; data derived from 11 independent experiments. (B, C) Graph displaying results of histopathological scoring of (B) perivascular edema and (C) alveolar edema in H&E-stained lung sections. Scoring 0 = none, 1 = scattered, 2 = low grade, 3 = medium grade, 4 = severe, 5 = massive. Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Data are displayed as box plots; middle line displays median, box indicates first and third quartiles, and whiskers indicate minimum to maximum. n = 3–6; data derived from six independent experiments. (D) Representative H&E staining of murine lungs. Upper panels display representative perivascular edema, ovals highlight perivascular hemorrhage, and # highlights alveolar hemorrhage only found in heparinase-treated groups. Lower panels display representative alveolar edema in corresponding groups indicated by dotted circles. Scale bars, 20 μm. (A–C) Significance tested between treatments (PBS ctr and enzymes) for sham (PBS ctr) and S.pn.-infected groups and between sham (PBS ctr) and S.pn-infected per treatment. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

To qualitatively determine the direct effects of transnasal fluid inoculation and enzymatic treatments on the alveolar glycocalyx ultrastructure, we examined alcian blue–stained tissue samples with transmission electron microscopy at 2 hpi and compared them with samples from untreated WT mice (Figures E7A–E7C). Alcian blue is a cytochemical dye that binds to negative charges, such as the ones highly present on GAG molecules, and has been used to visualize the glycocalyx by light and electron microscopy. At the electron microscopic level, positive alcian blue staining results in electron-dense precipitates; however, the degree of electron density depends on many factors and does not necessarily correlate with the amount of GAGs present. In uninfected mice, after hyaluronidase treatment, the electron-dense alcian blue layer seemed to be unchanged, whereas after heparinase treatment, we observed areas that were less electron dense than PBS-treated (Figure E7A) or nontreated lungs (Figure E7C). After bacterial infection, the PBS-treated samples showed disorganized filamentous stained material (Figure E7B), which may come from cell debris or inactivated surfactant lipid structures. After infection and heparinase treatment, we observed a denser layer on top of and around the microvilli, suggestive of proteinaceous material potentially coming from extravascular fluid. Interestingly, infected hyaluronidase-treated samples (Figure E7B) showed less dense but more staining around the microvilli than that observed with the enzymatic treatment alone (Figure E7A). We can therefore conclude that the ultrastructure of the alveolar epithelial glycocalyx changed with enzymatic treatment and infection; however, a formal quantification of glycocalyx loss was not feasible.

To directly assess the barrier integrity and viability of enzyme-treated and infected alveolar epithelial cells (HPAECs), we used an impedance-based in vitro method (ECIS) to record changes in monolayer resistance after treatment and infection over time. Employing a low-frequency alternating current, reduction in measured resistance represents loss of cell–cell contacts (barrier function loss), whereas decrease of resistance to levels of cell-free electrodes indicates cell detachment (viability loss). HPAECs treated with hyaluronidase or PBS alone did not exhibit reduced resistance indicative of unaffected barrier function (Figure 7A), whereas heparinase treatment alone mildly reduced resistance in the early hours after exposure (Figure 7B). In combination with bacterial stimulation, pretreatment with either enzyme resulted in accelerated disruption of the epithelial barrier, albeit much more rapidly after heparinase treatment (Figure 7B). Furthermore, all cells with bacterial stimulation exhibited reduction in resistance levels indicative of barrier function loss that progressed to viability loss over time, whereas enzyme pretreatment accelerated this kinetic (Figures 7A and 7B).

Figure 7.

Human epithelial barrier function is impaired by enzymatic glycocalyx disruption in vitro. (A, B) Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurement by electric cell substrate impedance sensing to assess barrier function of human primary alveolar epithelial cells (HPAECs) after (A) Hya or (B) Hep or PBS treatment with subsequent S.pn. infection or mock infection (PBS ctr). Left: Continuous TEER measurements over time of two or three replicates of one representative experiment; n = 2–3. Right: Individual datapoints of TEER measurements across all experimental groups at designated time points during baseline and postinfection; summary data derived from two or three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Significant differences were tested between all groups. (C) Determination of alveolus-on-a-chip barrier integrity upon 24 hours of heparinase treatment and S.pn. infection by apparent permeability (Papp) measurement of tracer molecules. Experiment was performed two to four times with two or three different cell donors per group. Graph shows a summary of experiments and replicates. Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Significant differences were tested between all groups. (D) Immunofluorescence of HPAECs (HTII-280, green; zona occludens [ZO]-1, orange [pseudocolored]; DAPI, blue) on the alveolar side and human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs, VE-cadherin, green; DAPI, blue) on the vascular side. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Using a human alveolus-on-a-chip model (Figure E8), we determined that heparinase treatment alone resulted in a marginal increase in apparent permeability; however, in combination with S.pn. infection, apparent permeability levels were significantly increased compared with control groups (Figure 7C). Immunofluorescence analyses of the alveolus chip revealed that heparinase treatment during S.pn. infection resulted in signs of epithelial damage and loss of tight junction marker (zona occludens [ZO]-1), whereas the endothelium remained largely intact (Figure 7D). To further assess loss of glycocalyx, junctional proteins, and cellular cytotoxicity individually, we analyzed the mean fluorescence intensity of WGA and ZO-1 in HPAECs that were treated for 2 hours with heparinase in the presence or absence of S.pn. infection in vitro while also measuring lactate dehydrogenase in the culture supernatants to determine cytotoxicity (Figure E9). Heparinase treatment gave rise to a trend toward decreased mean fluorescence intensity of WGA and ZO-1 markers (Figures E9A–E9C) in HPAECs while also leading to a mild increase in lactate dehydrogenase release (Figure E9D), neither of which was statistically significant. Taken together, we conclude that enzymatic disruption of the glycocalyx in vitro results in rapid changes in epithelial barrier permeability that accelerates S.pn.-induced cellular cytotoxicity, whereas in vivo the exacerbated pathology likely results from a combination of lung barrier breakdown, enhanced bacterial growth, and proinflammatory mediators.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the significant role played by the glycocalyx in limiting the development and severity of pneumococcal disease in mice. Intranasal inoculation with S.pn. in the presence of hyaluronidase or heparinase caused more severe disease, resulting in increased pulmonary bacterial burden and inflammatory leukocyte recruitment. Targeting hyaluronan and heparan sulfate resulted in histopathological exacerbations that were manifested in perivascular and intraalveolar compartments, respectively. Heparinase treatment culminated in increased alveolar permeability in vivo and disruption of the epithelial barrier in primary alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. In addition, S.pn. infection, in combination with heparinase treatment, induced enhanced shedding of GAGs into BALF, whereas S.pn. infection induced desulfation of heparan sulfate.

Hyaluronan and heparan sulfate are the most abundant nonsulfated and sulfated GAGs found in the lungs, respectively, and are involved in a wide spectrum of physiological processes that affect tissue homeostasis (29). Heparan sulfate is a major contributor to the negative charge harbored by the glycocalyx (30), enabling retention of the positively charged chemokines (31) while also playing a role in masking of important leukocyte adhesion molecules such as selectins (32). Hyaluronan can act as a cell adhesion molecule and can regulate intercellular and cell–extracellular matrix interactions via its receptor CD44 (33). It is able to bind large volumes of water and has been shown to regulate extravascular lung water volume (34) as well as pulmonary edema during experimental lung injury (35). The importance of these GAGs in regulating pneumococci-induced damage, pulmonary inflammation, and epithelial barrier function during bacterial pneumonia, however, remain to be elaborated.

Our findings are in agreement with previous studies investigating hyaluronan in the context of lung edema and streptococcal infections. S.pn. has evolved the ability to hydrolyze hyaluronan to orchestrate invasion (25), whereas group A Streptococci can use hyaluronic acid capsular polysaccharide to bind epithelial CD44 during colonization of the mouse pharynx (36). Pneumococci may also exhibit strain-specific competence in using hyaluronan as a carbon source during colonization (37), but this was not evident in the invasive S.pn. serotype 3 strain used in our study. Heparan sulfate has previously been shown to interact with S.pn. (38) as well as various other respiratory pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2 (39) and S. aureus (40).

Regardless of which GAG was targeted, the mice in our study exhibited significantly higher bacterial burden in the lungs, coupled to intraalveolar growth of pneumococci after heparinase treatment, together with abundant and diffuse distribution of pneumococci within the perivascular interstitium after hyaluronidase treatment. The majority of histopathological findings, such as hemorrhages, neutrophilic infiltrates, and edema, seen in intraalveolar and intrabronchiolar regions were more prominent in the heparinase-treated group, whereas hyaluronidase treatment could be distinguished by pronounced effects on the lung vasculature. This is in line with the prominent role of intact pulmonary hyaluronan for maintaining vascular homeostasis and preventing leakiness (41). Accordingly, we detected increased splenic bacterial burden, perivascular edema, and adventitial neutrophil extravasation and significantly elevated proinflammatory cytokine concentrations in the plasma of hyaluronidase-treated mice.

Heparinase treatment, on the other hand, gave rise to elevated chemokine and cytokine concentrations in the BALF, including CXCL1, CXCL5, IL-6, and TNF-α. Considering that endothelial heparan sulfate may bind to and regulate transcytosis of chemokines such as IL-8 (31), it is likely that the intact glycocalyx also binds and stores neutrophil chemoattractants. In addition, it is known that heparan sulfate can act as a ligand for neutrophil L-selectin to regulate tissue extravasation (42). Studies have shown that intact, unfractionated heparin binds to and potently inhibits binding of L- and P-selectin to other ligands, whereas fractionated low-molecular-weight heparin molecules lose this ability (43). Accordingly, we observed that treatment with heparinase, which cleaves sulfated saccharides from heparin (44), resulted in the highest number of neutrophils infiltrating into alveolar spaces during S.pn. infection. Furthermore, heparinase treatment also increased alveolar permeability during pneumococcal pneumonia, a finding we could reproduce in vitro in human models of epithelial barrier function (alveolus-on-a-chip and ECIS) after heparinase treatment and S.pn. infection of HPAECs. The sharp increase in permeability of the alveolus chip after heparinase treatment and S.pn. infection thus indicates the synergistic effect of loss of heparan sulfate and bacterial infection on rapid epithelial disintegration and loss of barrier function. Thus, targeting heparan sulfate may have a multipronged effect on pneumonia pathology, enhancing the availability of chemokines and adhesion molecules, increasing barrier permeability, and driving loss of epithelial integrity.

The recent demonstrations that alveolar heparan sulfate can be actively shed into the airways during lung inflammation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (9), in an LPS-mediated experimental model of acute lung injury (9), and after influenza infection in mice (45) are in line with our observations. We observed increased GAG shedding into BAL upon heparinase treatment, but only in infected mice, indicating that it is an active process driven by pneumococcal pneumonia. WGA lectin, which targets sialic acid and N-acetylglucosamine residues (the latter found in GAGs such as hyaluronan and heparan sulfate) (46, 47), was used to stain murine lungs, revealing that lectin signal derived from alveolar epithelial cells was not reduced after S.pn. infection or enzyme treatment 48 hpi. Lectin signal derived from endothelial cells, however, was reduced in S.pn.-infected mice independent of enzymatic treatment. These findings suggest that in contrast to the epithelial glycocalyx, the endothelial glycocalyx may have lower capacity to reconstitute N-acetylglucosamine–harboring GAGs (as stained by WGA). Indeed, a recent study has shown that the endothelial glycocalyx has regenerative potential after nonseptic degradation but that its reconstitution may be abrogated or delayed during sepsis (14). This notion is well in line with our finding that S.pn.-infected mice, with or without enzymatic treatment, had reduced endothelial WGA signal, possibly due to local inflammatory effects or bacteremia, including dissemination of bacteria into the spleen and subsequent systemic inflammation during pneumococcal pneumonia. When probed in vitro, we observed modest changes in epithelial permeability of HPAECs after 2 hours of heparinase treatment, which accelerated S.pn.-induced cell death over the infection time course, suggesting that small changes in epithelial barrier integrity may pave the way for bacteria to exploit and trigger enhanced pathology. In addition, we found that in contrast to control mice, the BALF of infected mice contained predominantly unsulfated heparin disaccharides. Although it is possible that pneumococci are directly involved in desulfation of heparin disaccharides through bacterial sulfatases, heparin desulfation was also described in an LPS-mediated acute lung injury model in mice in the absence of live bacterial infection (9), indicating that remodeling of heparan sulfate can be mediated not only by microbes but also by the host. The removal of highly sulfated moieties may further exacerbate infection-induced pulmonary inflammation, because it has been shown that only unfractionated, sulfated heparin is able to block selectin-mediated cell adhesion (48). Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that highly sulfated motifs of heparan sulfate also inhibit pneumococcal adhesion to host extracellular matrix, resulting in attenuation of corneal infection (49). Because some pneumococcal strains may express putative sulfatases in genomic islands (50), it is possible that S.pn. sulfatases may contribute to remodeling of heparan sulfate to reduce the fraction of sulfated moieties in favor of its virulence. One limitation of our study is the lack of in-depth transcriptional analysis of S.pn. during infection of the host, particularly in relation to expression of sulfatases. Unfortunately, the published draft genome sequence of the S.pn. serotype 3 NCTC7978 we used in this study (51) lacks the sulfatase genes denoted in the genomic island shown to be present in the S.pn. serotype 3 strain (OXC141, ST180).

In conclusion, our study shows the critical importance of pulmonary hyaluronan and heparan sulfate in controlling pneumococcal virulence, disease severity, and pulmonary inflammation in mice. Further investigations into the mechanisms of GAG shedding and remodeling, especially in the context of host–pathogen interactions, would provide valuable contributions to infectious disease research and respiratory medicine.

Supplemental Materials

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Ulrike Behrendt, John Horn, and Katja Doerfel for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) project ID 431232613 – SFB 1449, subproject B02 (M.W. and G.N.), subproject B01 (M.O.), and subprojects C03 and Z01 (K.P.) and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant SFB TR84, subproject Z01b (A.D.G.) and subprojects C06 and C09 (M.W.) and grant SFB 1340-372486779, subproject C02 (K.P.); Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) - MAPVAP grant 16GW0247 (G.N. and M.W.); BMBF - e:Med CAPSyS grant 01ZX1604B (M.W.); BMBF - e:Med SYMPATH grant 01ZX1906A (M.W.); Sanitätsakademie der Bundeswehr SoFo39K4 (C.M.Z.) and E/U2ED/PD014/OF550 (M.W. and G.N.); Charité 3R grant (C.G.); Jürgen Manchot Foundation Stipend (K.A.K.L.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions: C.G., K.A.K.L., K.H., and G.N. performed experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data. A.N. and S.M.K.S. performed experiments. E.L.-R., V.G., and S.T. performed electron microscopic analysis and interpreted the data. M.O. interpreted and supervised electron microscopic studies. A.V. and S.K. performed histopathology and interpreted the data. A.D.G. interpreted and supervised histopathology. A.Z. performed high-performance liquid chromatography analysis and interpreted the data. K.P. interpreted and supervised high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. C.M.Z. provided resources and interpreted chip data. M.W. interpreted data. G.N., C.G., and K.A.K.L. drafted the manuscript. K.H., E.L.-R., A.V., S.K., A.Z., and A.D.G. wrote sections of the manuscript. G.N. conceived the study and supervised the work. All authors revised and edited the manuscript and approved the final submitted version for publication.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible at the Supplements tab.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2024-0003OC on July 23, 2024

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax . 2012;67:71–79. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghia CJ, Dhar R, Koul PA, Rambhad G, Fletcher MA. Streptococcus pneumoniae as a cause of community-acquired pneumonia in Indian adolescents and adults: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med . 2019;13:1179548419862790. doi: 10.1177/1179548419862790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howard LS, Sillis M, Pasteur MC, Kamath AV, Harrison BD. Microbiological profile of community-acquired pneumonia in adults over the last 20 years. J Infect . 2005;50:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrer M, Travierso C, Cilloniz C, Gabarrus A, Ranzani OT, Polverino E, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: characteristics and prognostic factors in ventilated and non-ventilated patients. PLoS One . 2018;13:e0191721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ewig S, Woodhead M, Torres A. Towards a sensible comprehension of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive Care Med . 2011;37:214–223. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mongardon N, Max A, Bougle A, Pene F, Lemiale V, Charpentier J, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of severe pneumococcal pneumonia admitted to intensive care unit: a multicenter study. Crit Care . 2012;16:R155. doi: 10.1186/cc11471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. ARDS Definition Task Force Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA . 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Niederman MS, Torres A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir Rev . 2022;31:220123. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0123-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haeger SM, Liu X, Han X, McNeil JB, Oshima K, McMurtry SA, et al. Epithelial heparan sulfate contributes to alveolar barrier function and is shed during lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2018;59:363–374. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0428OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mockl L. The emerging role of the mammalian glycocalyx in functional membrane organization and immune system regulation. Front Cell Dev Biol . 2020;8:253. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haeger SM, Yang Y, Schmidt EP. Heparan sulfate in the developing, healthy, and injured lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2016;55:5–11. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0043TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ochs M, Hegermann J, Lopez-Rodriguez E, Timm S, Nouailles G, Matuszak J, et al. On top of the alveolar epithelium: surfactant and the glycocalyx. Int J Mol Sci . 2020;21:3075. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Florian JA, Kosky JR, Ainslie K, Pang Z, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a mechanosensor on endothelial cells. Circ Res . 2003;93:e136–e142. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000101744.47866.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Y, Haeger SM, Suflita MA, Zhang F, Dailey KL, Colbert JF, et al. Fibroblast growth factor signaling mediates pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx reconstitution. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2017;56:727–737. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0338OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weinbaum S, Zhang X, Han Y, Vink H, Cowin SC. Mechanotransduction and flow across the endothelial glycocalyx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2003;100:7988–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332808100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reitsma S, Slaaf DW, Vink H, van Zandvoort MA, Oude Egbrink MG. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch . 2007;454:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van den Berg BM, Vink H, Spaan JA. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res . 2003;92:592–594. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065917.53950.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alphonsus CS, Rodseth RN. The endothelial glycocalyx: a review of the vascular barrier. Anaesthesia . 2014;69:777–784. doi: 10.1111/anae.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang G, Tiemeier GL, van den Berg BM, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial glycocalyx hyaluronan: regulation and role in prevention of diabetic complications. Am J Pathol . 2020;190:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoogewerf AJ, Kuschert GS, Proudfoot AE, Borlat F, Clark-Lewis I, Power CA, et al. Glycosaminoglycans mediate cell surface oligomerization of chemokines. Biochemistry . 1997;36:13570–13578. doi: 10.1021/bi971125s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rizzo AN, Haeger SM, Oshima K, Yang Y, Wallbank AM, Jin Y, et al. Alveolar epithelial glycocalyx degradation mediates surfactant dysfunction and contributes to acute respiratory distress syndrome. JCI Insight . 2022;7:e154573. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.154573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sjogren J, Collin M. Bacterial glycosidases in pathogenesis and glycoengineering. Future Microbiol . 2014;9:1039–1051. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol . 2018;16:355–367. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitchell AM, Mitchell TJ. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors and variation. Clin Microbiol Infect . 2010;16:411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berry AM, Lock RA, Thomas SM, Rajan DP, Hansman D, Paton JC. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus pneumoniae hyaluronidase gene and purification of the enzyme from recombinant Escherichia coli. Infect Immun . 1994;62:1101–1108. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1101-1108.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Timm S, Lettau M, Hegermann J, Rocha ML, Weidenfeld S, Fatykhova D, et al. The unremarkable alveolar epithelial glycocalyx: a thorium dioxide-based electron microscopic comparison after heparinase or pneumolysin treatment. Histochem Cell Biol . 2023;160:83–96. doi: 10.1007/s00418-023-02211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goekeri C, Linke KAK, Hoffmann K, Lopez-Rodriguez E, Gluhovic V, Voß A, et al. Enzymatic modulation of the pulmonary glycocalyx alters susceptibility to Streptococcus pneumoniae [preprint] 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. Szulcek R, Bogaard HJ, van Nieuw Amerongen GP. Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing for the quantification of endothelial proliferation, barrier function, and motility. J Vis Exp . 2014;(85):51300. doi: 10.3791/51300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Souza-Fernandes AB, Pelosi P, Rocco PR. Bench-to-bedside review: the role of glycosaminoglycans in respiratory disease. Crit Care . 2006;10:237. doi: 10.1186/cc5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lieleg O, Baumgartel RM, Bausch AR. Selective filtering of particles by the extracellular matrix: an electrostatic bandpass. Biophys J . 2009;97:1569–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Middleton J, Neil S, Wintle J, Clark-Lewis I, Moore H, Lam C, et al. Transcytosis and surface presentation of IL-8 by venular endothelial cells. Cell . 1997;91:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luo J, Kato M, Wang H, Bernfield M, Bischoff J. Heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans inhibit E-selectin binding to endothelial cells. J Cell Biochem . 2001;80:522–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miyake K, Underhill CB, Lesley J, Kincade PW. Hyaluronate can function as a cell adhesion molecule and CD44 participates in hyaluronate recognition. J Exp Med . 1990;172:69–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhattacharya J, Cruz T, Bhattacharya S, Bray BA. Hyaluronan affects extravascular water in lungs of unanesthetized rabbits. J Appl Physiol (1985) . 1989;66:2595–2599. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.6.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nettelbladt O, Tengblad A, Hallgren R. Lung accumulation of hyaluronan parallels pulmonary edema in experimental alveolitis. Am J Physiol . 1989;257:L379–L384. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1989.257.6.L379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cywes C, Stamenkovic I, Wessels MR. CD44 as a receptor for colonization of the pharynx by group A Streptococcus. J Clin Invest . 2000;106:995–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marion C, Stewart JM, Tazi MF, Burnaugh AM, Linke CM, Woodiga SA, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae can utilize multiple sources of hyaluronic acid for growth. Infect Immun . 2012;80:1390–1398. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05756-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tonnaer EL, Hafmans TG, Van Kuppevelt TH, Sanders EA, Verweij PE, Curfs JH. Involvement of glycosaminoglycans in the attachment of pneumococci to nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Microbes Infect . 2006;8:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clausen TM, Sandoval DR, Spliid CB, Pihl J, Perrett HR, Painter CD, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell . 2020;183:1043–1057.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liang OD, Ascencio F, Fransson LA, Wadstrom T. Binding of heparan sulfate to Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun . 1992;60:899–906. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.899-906.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Singleton PA, Mirzapoiazova T, Guo Y, Sammani S, Mambetsariev N, Lennon FE, et al. High-molecular-weight hyaluronan is a novel inhibitor of pulmonary vascular leakiness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2010;299:L639–L651. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00405.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hayward R, Nossuli TO, Lefer AM. Heparinase III exerts endothelial and cardioprotective effects in feline myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther . 1997;283:1032–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koenig A, Norgard-Sumnicht K, Linhardt R, Varki A. Differential interactions of heparin and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans with the selectins. Implications for the use of unfractionated and low molecular weight heparins as therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest . 1998;101:877–889. doi: 10.1172/JCI1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mourier P. Heparinase digestion of 3-O-sulfated sequences: selective heparinase II digestion for separation and identification of binding sequences present in ATIII affinity fractions of bovine intestinal heparins. Front Med (Lausanne) . 2022;9:841726. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.841726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Langouet-Astrie C, Oshima K, McMurtry SA, Yang Y, Kwiecinski JM, LaRiviere WB, et al. The influenza-injured lung microenvironment promotes MRSA virulence, contributing to severe secondary bacterial pneumonia. Cell Rep . 2022;41:111721. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kubota Y, Fujioka K, Takekawa M. WGA-based lectin affinity gel electrophoresis: a novel method for the detection of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins. PLoS One . 2017;12:e0180714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zeng Y, Ebong EE, Fu BM, Tarbell JM. The structural stability of the endothelial glycocalyx after enzymatic removal of glycosaminoglycans. PLoS One . 2012;7:e43168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang L, Brown JR, Varki A, Esko JD. Heparin’s anti-inflammatory effects require glucosamine 6-O-sulfation and are mediated by blockade of L- and P-selectins. J Clin Invest . 2002;110:127–136. doi: 10.1172/JCI14996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hayashida A, Saeed HN, Zhang F, Song Y, Liu J, Parks WC, et al. Sulfated motifs in heparan sulfate inhibit Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesion onto fibronectin and attenuate corneal infection. Proteoglycan Res . 2023;1:e9. doi: 10.1002/pgr2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McAllister LJ, Ogunniyi AD, Stroeher UH, Paton JC. Contribution of a genomic accessory region encoding a putative cellobiose phosphotransferase system to virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS One . 2012;7:e32385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hahn C, Harrison EM, Parkhill J, Holmes MA, Paterson GK. Draft genome sequence of the Streptococcus pneumoniae Avery strain A66. Genome Announc . 2015;3:e00697-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00697-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.