Abstract

Objective

In addition to the surface hemorrhage of cancellous bone after large‐area osteotomy, the intramedullary hemorrhage after the reamed knee joint is also a major cause of postoperative bleeding after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of bone wax application at different time points of prone hemorrhage to reduce perioperative blood loss.

Methods

From August 2023 to December 2023, 150 patients undergoing primary unilateral TKA were included in this prospective, randomized controlled trial, patients were randomly divided into three groups: group A, after autogenous osteotomy plug was used to fill the femoral medullary cavity, the residual space was sealed with bone wax and the exposed cancellous bone surface around the prosthesis was coated with bone wax after the prosthesis adhesion; group B, only the exposed cancellous bone surface around the prosthesis was coated with bone wax; and group C, no bone wax was used. The primary outcome was total perioperative blood loss. Secondary outcomes included occult blood loss, postoperative hemoglobin reduction, blood transfusion rate, lower limb diameter, and knee function, while length of hospital stay was recorded. Tertiary outcomes included the incidence of postoperative related adverse events.

Results

The total blood loss in group A (551.5 ± 224.5 mL) and group B (656.3 ± 267.7 mL) was significantly lower than that in group C (755.3 ± 248.3 ml, p < 0.001), and the total blood loss in group A was also lower than that in group B (p < 0.05). There were also significant differences in the reduction of hemoglobin level and hidden blood loss among the three groups (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant improvement in postoperative lower limb swelling, knee joint activity and hospitalization time; there was no significant difference in the incidence of complications such as thromboembolism.

Conclusion

The use of bone wax in TKA can safely and effectively reduce perioperative blood loss and hemoglobin drop rate, and multiple use at time points during the operation when blood loss is prone to occur can produce more significant hemostatic effect.

Keywords: Blood loss, Bone wax, Perioperative blood management, Safety, Total knee arthroplasty

In addition to surface hemorrhage of cancellous bone after large‐area osteotomy, intramedullary hemorrhage after the knee joint is also a major cause of postoperative bleeding after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of bone wax application at different time points during prone hemorrhage to reduce perioperative blood loss. Finally, it was found that the use of bone wax in TKA can safely and effectively reduce perioperative blood loss and the rate of decrease in hemoglobin, and multiple use steps during surgery, when blood loss is prone to occur, can produce more significant hemostatic effects.

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most successful orthopedic procedures for relieving pain in patients with end‐stage knee degenerative disease. From 2005 to 2030, the annual demand for primary TKA in the United States is expected to increase by 673% to 3.48 million cases. 1 Blood loss and anemia are common complications after TKA, and long‐term anemia after TKA is also an independent risk factor for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI). 2 It has been reported that the maximum blood loss after TKA can reach 1790 ml, which not only affects the recovery of knee function but also leads to higher allogeneic transfusion rates. Allogeneic transfusion is not without risks. It may lead to allergic reactions, transfusion reactions and a great risk of disease transmission, as well as aggravating the financial burden on patients. 3 , 4 Many studies are currently focused on optimizing perioperative blood management in patients to reduce the need for allogeneic transfusion and the occurrence of complications. 5 For example, autologous blood transfusion, intraoperative controlled hypotension, fibrin tissue adhesives, erythropoietin and antifibrinolytic drugs are among the treatment strategies. 4 , 6 , 7 , 8

Bone wax is a centuries‐old material used as a topical hemostatic to control bleeding on fractured bone surfaces. It is composed of beeswax and vaseline and coagulates by physically plugging the capillaries in the cancellous bone marrow cavity and sealing the interosseous bleeding pathway to block the flow of cross‐sectional blood vessels. It has good softening properties, is simple to use, and is cost‐effective. 9 , 10 , 11

According to literature reports, nearly two‐thirds of the total blood loss after TKA is hidden blood loss. 12 , 13 In addition to the blood loss caused by large area osteotomy and extensive tissue dissection, the femoral alignment is located by opening the femoral medullary cavity in ordinary TKA surgery, and the bleeding of the medullary cavity after reaming has also become one of the important causes of massive bleeding after TKA. 14 When the femoral prosthesis is used without reaming or the femoral medullary cavity is blocked with bone wax, the blood loss after TKA can be significantly reduced. 15 , 16 , 17 Because the bleeding of the exposed cancellous bone surface after osteotomy can be controlled by bone wax, the control of the bleeding of the open medullary cavity at the femoral end has become the focus of research. At present, there are relatively few studies discussing the application of bone wax at different time points during TKA. 11 Therefore, we hypothesized that compared with the application of bone wax only on the cancellous bone surface around the prosthesis, the application of bone wax combined with autogenous osteotomy block to block the femoral medullary cavity can further reduce perioperative blood loss, and designed a prospective randomized controlled study to investigate the following questions: (i) whether the application of bone wax in TKA can effectively reduce perioperative blood loss and lower limb swelling; and (ii) whether repeated application of bone wax at other blood loss prone time points could further control perioperative blood loss.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our institution's clinical trial (ChiCTR2300078822) and biomedical ethics committees (number: 2023‐1917). All study participants received written informed consent from the patient or their guardian before enrollment.

Patient Recruitment

This prospective study enrolled patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis and scheduled for unilateral primary TKA at our institution from August to December 2023. Eligibility criteria were: (1) patients aged 50–80 years; (2) body mass index (BMI) of 18–36 kg/m2; and (3) American College of Anesthesiologists functional status I‐III. Patients were excluded if they had severe knee deformity on the operated side (≥20° flexion deformity, ≥20° varus deformity), preoperative anemia or hematologic disease, use of anticoagulants, lower extremity vascular disease, liver or kidney insufficiency, history of venous thromboembolism or stroke, coronary stenting within the past 12 months, or a proposed revision surgery. We also excluded patients who were unable to communicate or who refused to participate in the study. Finally, 150 patients were enrolled in the study, divided into: multiple applications of bone wax group; single application of bone wax group; and control group, 50 in each group.

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups using a computer‐generated random number table, with neither the patient nor the outcome evaluator being aware of the randomization. The random numbers were sealed in opaque envelopes by an independent observer, and the patient was asked to select one of the sealed envelopes on the morning of the operation to determine the treatment group. Data analysis was performed by a statistician, who was also unaware of the treatment group assignments.

Surgical Technique and Perioperative Management

All TKAs were performed by the same senior surgeon; patients received general anesthesia and post‐stabilized cemented prosthesis (DePuy Synthes, Raynham, MD, USA) was implanted; a tourniquet (pressure 300 mmHg) was prepositioned at the thigh root, using a medial parapatellar approach, anterior median surgical incision. The surgery was performed using standard techniques, and no patients received patella replacement. The surgical area was washed with a medical irrigator. No postoperative drainage was placed, the incision was closed layer by layer, and the wound was compressed with cotton pads. In group A, bone wax was used to seal the residual femoral medullary cavity based on the use of autogenous osteotomy block as a plug to fill the femoral medullary cavity, and after the prosthesis was cemented, bone wax was firmly coated on the exposed cancellous bone surface around the femoral and tibial prosthesis; in group B, after cementation of the prosthesis, a thin, uniform layer of bone wax was applied to the exposed cancellous bone surface around the femoral and tibial prostheses; no bone wax was used in group C. All patients received an intravenous injection of 1000 mg of tranexamic acid before skin incision. Patients were instructed in passive and active physical therapy after anesthesia recovery, quadriceps contraction training and walking with a walker during hospitalization. Low molecular weight heparin (Clexane, Paris, France) was given at a dose of 0.2 ml 10–12 h after surgery, followed by a daily dose of 0.4 ml until discharge. After discharge, patients were given 10 mg rivaroxaban daily for 2 weeks to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Patients were assessed daily for symptomatic VTE, with routine Doppler ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) screening at 14 days and 3 months after surgery, and with computed tomography if pulmonary embolism (PE) was suspected. Blood transfusion was required when hemoglobin (Hb) concentration was below 70 g/l or 70 g/l < Hb < 100 g/l but dizziness, fatigue, and other apparent anemia were observed.

Outcome Measures

Demographic data and general information (age, gender, body mass index [BMI] and American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] score) were collected on admission, as well as the surgical side, preoperative Hb, Hematocrit (HCT), and coagulation were collected.

The main postoperative index was total blood loss (TBL); secondary indexes included hidden blood loss (HBL), intraoperative blood loss (IBL), blood transfusion rate, postoperative hemoglobin decline rate, lower limb diameter on the 1st and 3rd day after operation, knee function recovery at 24, 48, and 72 h after surgery (Hospital for Special Surgery [HSS] score, daily walking distance, and knee range of motion [ROM] measured with a protractor), visual analogue scale [VAS] was used to evaluate postoperative thigh pain, length of stay [LOS], and incidence of symptomatic thromboembolic events or other complications (wound dehiscence, infection, etc.). IBL was calculated by measuring the negative pressure suction canister aspiration volume and gauze weight increase at the end of the operation, and HBL was defined as TBL minus IBL; 12 the perioperative lower limb diameter was measured in the following three areas: 10 cm above the upper patella (thigh circumference); the upper patella (patella circumference); and the maximum circumference of the calf (calf circumference). If allogeneic blood transfusion or infusion was performed, the transfusion was added to the total blood loss calculation. The TBL volume was calculated according to the Gross formula as follows: 18 TBL (ml) = preoperative blood volume (PBV) × (preoperative HCT level − postoperative HCT level on the 3rd day) / the average of preoperative and postoperative HCT. PBV was calculated using the Nadler formula: 19 PBV = k1 × height3 + k2 × weight + k3. k1 = 0.3669, k2 = 0.03219, k3 = 0.6041 for men, and k1 = 0.3561, k2 = 0.03308, k3 = 0.1833 for women.

Data Analysis

Sample size was calculated based on previous studies, which required 47 patients in each group to detect a difference in 100 ml of blood loss at a two‐sided alpha level of 0.05 and power of 90%; we decided to include at least 50 patients in each group to account for loss to follow‐up and exclusion.

For continuous data with normal distribution, we used one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the least significant difference test. For continuous variables with skewness, we used Kruskal–Wallis one‐way analysis of variance with a post hoc test. For categorical data, we used the Pearson chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and categorical data were expressed as numbers or percentages. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). A difference was considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic Data

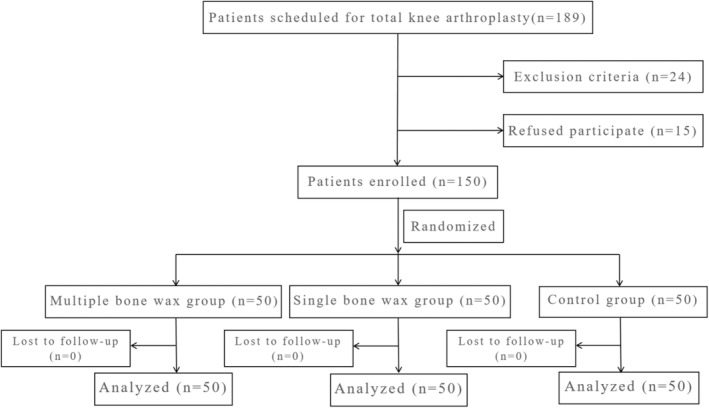

A total of 189 patients underwent eligibility assessment, of whom 24 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 15 declined to participate. Thus, 150 eligible patients were finally enrolled, and no patients were excluded from analysis during the postoperative evaluation of postoperative outcomes. The flow chart of participants is shown in Figure 1, with 50 patients in each of the multiple‐application group, single‐application group, and control group. There were no significant differences in preoperative demographic and characteristics among the three groups (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of patients' selection and exclusion.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Characteristic | Group A (n = 50) | Group B (n = 50) | Group C (n = 50) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 12/38 | 16/34 | 11/39 | 0.483 b |

| Age (years) | 64.2 ± 8.5 | 66.1 ± 8.2 | 64.8 ± 8.6 | 0.545 a |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 3.8 | 25.4 ± 3.9 | 24.4 ± 4.1 | 0.432 a |

| ASA status (I/II/III) | 6/34/10 | 9/28/13 | 7/32/11 | 0.801 b |

| Operated side (right/left) | 26/24 | 28/22 | 23/27 | 0.602 b |

| Time of operation (min) | 69.1 ± 16.4 | 67.2 ± 13.6 | 66.0 ± 12.8 | 0.556 c |

| Preoperative values | ||||

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.1 ± 1.1 | 13.4 ± 1.3 | 13.3 ± 1.2 | 0.430 a |

| Hct (%) | 40.1 ± 3.9 | 41.5 ± 4.4 | 40.3 ± 4.2 | 0.193 a |

| PLT (×109/l) | 217.8 ± 72.3 | 231.4 ± 63.3 | 210.6 ± 68.6 | 0.305 a |

| INR | 1.02 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.09 | 1.03 ± 0.10 | 0.410 a |

| D‐dimer (mg/l FEU) | 0.87 ± 0.49 | 0.93 ± 0.55 | 0.96 ± 0.52 | 0.667 a |

| Knee ROM (°) | 109.2 ± 7.5 | 107.4 ± 6.9 | 110.2 ± 7.6 | 0.119 a |

| Lower extremity circumference (cm) | ||||

| Thigh | 41.3 ± 4.8 | 43.0 ± 4.9 | 41.8 ± 5.4 | 0.220 a |

| Patella | 36.7 ± 3.5 | 37.7 ± 3.7 | 36.3 ± 3.3 | 0.215 a |

| Calf | 32.8 ± 3.4 | 33.7 ± 3.6 | 33.4 ± 3.5 | 0.445 a |

Notes: Values are mean ± SD or number of cases.

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; FEU, fibrinogen equivalent unit; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; INR, international normalized ratio; PLT, platelet count; ROM, range of motion.

One‐way analysis of variance.

Pearson's chi‐squared test.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

Primary Outcomes

The average TBL in group C (755.3 ± 248.3 ml) was significantly higher than that in group A (551.5 ± 224.5 ml) and group B (656.3 ± 267.7 ml), with statistically significant differences (p < 0.001); and the average TBL in group B was also significantly higher than that in group A (p = 0.036) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Outcome measures of blood loss.

| Outcome | Group A (n = 50) | Group B (n = 50) | Group C (n = 50) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A vs. B vs. C | A vs. B | A vs. C | B vs. C | ||||

| TBL (mL) | 551.5 ± 224.5 | 656.3 ± 267.7 | 755.3 ± 248.3 | <0.001 a | 0.036 a | <0.001 a | 0.047 a |

| IBL (mL) | 100.2 ± 27.2 | 98.2 ± 25.9 | 106.2 ± 27.2 | 0.302 a | |||

| HBL (mL) | 451.3 ± 227.2 | 558.1 ± 269.5 | 649.1 ± 248.6 | 0.001 a | 0.034 a | <0.001 a | 0.070 a |

| Serum Hb level (g/dl) | |||||||

| POD 1 | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 11.7 ± 1.1 | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 0.020 a | 0.662 a | 0.028 a | 0.009 a |

| POD 3 | 10.5 ± 1.0 | 10.4 ± 1.1 | 9.7 ± 0.9 | <0.001 a | 0.604 a | <0.001 a | <0.001 a |

| Change in Hb level (g/dl) | |||||||

| POD 1 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 0.002 a | 0.218 a | 0.001 a | 0.022 a |

| POD 3 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | <0.001 a | 0.045 a | <0.001 a | 0.006 a |

Abbreviations: HBL, hidden blood loss; IBL, intraoperative blood loss; POD, postoperative day; TBL, total blood loss.

One‐way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni test.

Secondary Outcomes

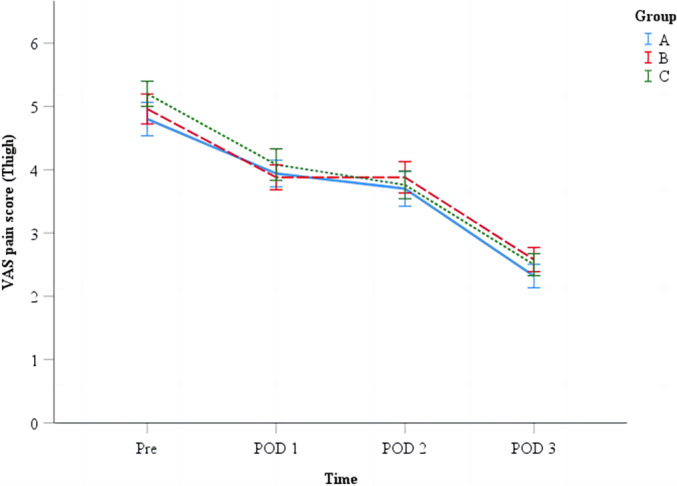

Similarly, the mean HBL in group A (451.3 ± 227.2 mL) and Group B (558.1 ± 269.5 mL) was significantly lower than that in group C (649.1 ± 248.6 mL) (p = 0.001); the mean HBL in group A was significantly lower than that in group B (p = 0.034). There was a significant difference in the decrease in Hb levels on the first day after surgery among the three groups (group A: 1.5 ± 0.8 g/dl; group B: 1.8 ± 0.8 g/dl; group C: 2.2 ± 1.0 g/dl; p = 0.002), with no significant difference between group A and group B (p = 0.218). There was also a significant difference in the decrease in Hb levels on the third day after surgery among the three groups (group A: 2.6 ± 0.9 g/dl; group B: 3.0 ± 1.0 g/dl; group C: 3.6 ± 1.2 g/dl; p < 0.001), and a significant difference between group A and group B (p = 0.045) (Table 2). Only one patient in group C received postoperative blood transfusion due to an Hb level < 7 g/dl, with no significant difference in the rate of blood transfusion among the three groups (p = 0.170). Bone wax did not significantly affect postoperative lower limb swelling and knee joint function recovery (daily walking distance, HSS score, range of motion) (Table 3), nor did it significantly affect pain score (p > 0.05) (Figure 2). There were also no significant differences in IBL and LOS among the groups (p = 0.302, p = 0.475). There was no difference in the occurrence of thromboembolic complications among the three groups (p = 0.034), with calf muscle venous thrombosis occurring in three patients in Group A, six patients in Group B, and four patients in Group C.

TABLE 3.

Postoperative functional recovery.

| Outcome | Group A (n = 50) | Group B (n = 50) | Group C (n = 50) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thigh (cm) | ||||

| POD 1 | 42.0 ± 5.4 | 44.0 ± 5.5 | 42.3 ± 6.1 | 0.170 a |

| POD 3 | 42.6 ± 5.1 | 44.4 ± 5.5 | 43.1 ± 5.7 | 0.279 a |

| Patella (cm) | ||||

| POD 1 | 37.3 ± 4.0 | 38.2 ± 3.7 | 37.4 ± 3.5 | 0.457 a |

| POD 3 | 37.9 ± 4.1 | 38.7 ± 3.9 | 38.2 ± 4.0 | 0.649 a |

| Calf (cm) | ||||

| POD 1 | 33.6 ± 3.9 | 34.6 ± 3.9 | 34.0 ± 3.8 | 0.458 a |

| POD 3 | 33.9 ± 4.0 | 35.1 ± 3.8 | 34.6 ± 4.0 | 0.311 a |

| Knee ROM (°) | ||||

| POD 1 | 99.9 ± 9.2 | 98.5 ± 10.2 | 101.5 ± 10.1 | 0.316 a |

| POD 3 | 108.2 ± 9.0 | 106.8 ± 8.8 | 108.7 ± 9.3 | 0.554 a |

| Ambulation distance (m) | ||||

| POD 1 | 31.3 ± 9.4 | 28.8 ± 8.5 | 32.2 ± 10.8 | 0.198 a |

| POD 3 | 48.7 ± 13.1 | 45.8 ± 10.4 | 46.9 ± 13.5 | 0.492 a |

| HSS score | ||||

| POD 1 | 58.1 ± 8.7 | 57.4 ± 10.9 | 55.8 ± 9.9 | 0.482 a |

| POD 3 | 65.8 ± 10.4 | 63.3 ± 8.2 | 63.6 ± 9.4 | 0.335 a |

| LOS (h) | 72.8 ± 13.3 | 74.2 ± 12.4 | 76.1 ± 14.4 | 0.475 a |

Abbreviation: LOS, length of stay.

One‐way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni test.

FIGURE 2.

Differences in VAS scores of thigh pain. VAS = visual analogue scale. POD = postoperative day.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of bone wax at several time points during TKA when blood loss is prone. The results showed that bone wax during TKA reduced total and hidden blood loss, and further reduced perioperative blood loss when the residual gap was closed with bone wax after autologous bone plug was filled into the femoral medullary cavity. However, bone wax did not affect postoperative lower limb swelling or improve joint motion. Bone wax application did not increase the incidence of related complications.

Advantages of Intraoperative Application of Bone Wax to Control Blood Loss

The perioperative blood loss of TKA is relatively large, and up to 65% of the bleeding occurs within 8 h after surgery. 20 It is estimated that about 20%–50% of patients need to receive allogeneic blood transfusion after surgery. 21 At present, how to reduce the blood loss after TKA has always been a concern of joint surgeons. In addition to the application of complete hemostasis of soft tissue during surgery, antifibrinolytic agents and tranexamic acid, 8 , 20 , 22 the use of some local hemostatic agents is also very effective. In a prospective randomized controlled study including 100 TKA patients, Moo et al. 11 found that the use of bone wax closure hemostasis can significantly reduce the total and hidden blood loss after TKA, which is consistent with our study. Mortazavi et al. also found that the use of bone wax on the femoral neck section in THA through direct anterior approach can significantly reduce the perioperative blood loss. 10 Another study also showed that the blood transfusion rate was significantly reduced after the application of bone wax in TKA, and only 2% of patients needed blood transfusion after surgery. 23

Effectiveness of Bone Wax Applied at Different Time Points Prone to Blood Loss on Perioperative Blood Loss and Lower Limb Swelling

The previous literature on the application of bone wax in TKA mostly focused on the application of bone wax on the uncovered bone surface around the prosthesis, and the blood loss of the femoral medullary cavity after osteotomy is also one of the main sources of blood loss after TKA. 24 Because the tourniquet is routinely used in TKA, there is no obvious difference in intraoperative blood loss. 25 , 26 , 27 Therefore, the blood loss mainly comes from hidden blood loss. 13 , 28 From the results of this study, we observed that the application of bone wax can significantly reduce the hidden blood loss after surgery. Furthermore, we found that the hidden blood loss of some patients who used osteotomes to seal the femoral medullary cavity and then used bone wax to seal the residual gaps around the medullary cavity was significantly lower than that of patients who only used bone wax around the prosthesis. The reason may be that the continuous bleeding of the open medullary cavity at the femoral end is an important part of hidden blood loss. Part of this bleeding is the continuous hemorrhage of the nutrient vessels at the osteotomy surface. When only the autogenous osteotomes were used to seal the femoral medullary cavity, there were still large or more residual gaps around the femoral medullary cavity. The hemorrhage of the nutrient vessels in the femoral medullary cavity can enter the joint cavity or tissue gap through these residual gaps, forming hidden blood loss. 14 Another part of the stimulation for the release of large amounts of free fatty acids during the medullary expansion operation can stimulate neutrophils to produce reactive oxygen species, which lead to peroxidative damage of red blood cells and hemoglobin membrane molecules, and finally cause hidden blood loss. 29 , 30 Related studies have also reported the adverse effect of bleeding from femoral intramedullary packing on TKA blood loss. A meta‐analysis showed that the use of femoral intramedullary bone plug significantly reduced blood loss and reduced the risk ratio of blood transfusion in patients undergoing TKA. 31 Another study suggested that filling the intramedullary canal with bone cement could also reduce the rate of postoperative hemoglobin drop and estimated blood loss. 32 However, other researchers disagree with this. Puri et al. found in a large retrospective cohort analysis that the removal of intramedullary instrumentation in the femur by computer‐assisted surgery did not reduce the rate of blood transfusion, and the difference in total blood loss was small. 33

Although the lower limb swelling rate after TKA is related to the early postoperative invisible blood loss and body mass index, 34 this study observed that the degree of postoperative lower limb swelling in patients with bone wax application was not improved. This may be because the body mass index of most patients included in our institution was below 25 kg/m2, and the degree of swelling was generally more obvious in 3–5 days after surgery; 34 another important reason may be that patients received timely postoperative pneumatic compression of ankle joint pump, which helped postoperative swelling subside and knee joint function recovery. 35 , 36

Strengths and Limitations

Reducing blood loss and lower limb swelling after TKA contributes to enhanced recovery after surgery. 34 , 37 This study is the first to evaluate the efficacy and safety of applying bone wax at different time points during surgery when blood loss is likely to occur, and also to discuss the effect of topical hemostatic agents on lower extremity swelling. The intervention method of intraoperative bone wax is not complicated and has good repeatability.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the calculation of blood loss was mainly based on the Hct value on the 3rd day after surgery, while the decline of perioperative Hb and Hct is not limited to 72 h after surgery, and longer periods of hemodilution may lead to inaccurate results. 38 , 39 However, there was no significant difference in the length of hospital stay among the three groups, so we believe that this calculation method does not affect the clinical significance of the results. Second, we did not evaluate the prosthesis coverage during the operation, and the exposed cancellous bone surface area of osteotomy is also related to HBL to some extent. 14 Finally, although the incidence of DVT, PE and other complications was observed to be low, no longer follow‐up was conducted, and a larger sample size and longer observation time may be needed in the future to fully evaluate the between‐group differences in these adverse events.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study shows that single application of bone wax around the prosthesis in TKA can effectively reduce the total perioperative blood loss and hidden blood loss, and reduce the decline of postoperative hemoglobin level. Re‐application of bone wax to seal the bone marrow gap at other time points prone to blood loss can more significantly reduce perioperative blood loss, and will not increase the incidence of early postoperative thromboembolism, infection and other adverse events.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Clinical Trials and Biomedical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital.

Author Contributions

YSW was responsible for conceptualized and designed the experiments, and GYF was responsible for data collection. LQH was responsible for data analysis. CLJ was responsible for manuscript writing. KPD was responsible for the supervision and communication of the entire research process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our sincere appreciation for all the patients that joined this study. This study was funded by 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence–Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, grant no. ZYJC18040.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dobson PF, Reed MR. Prevention of infection in primary THA and TKA. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5(10):604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kolin DA, Sculco PK, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Rodriguez JA, Ast MP, Chalmers BP. Risk factors for blood transfusion and postoperative anaemia following total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt J. 2023;105(10):1086–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frisch NB, Wessell NM, Charters MA, Yu S, Jeffries JJ, Silverton CD. Predictors and complications of blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loftus TJ, Spratling L, Stone BA, Xiao L, Jacofsky DJ. A patient blood management program in prosthetic joint arthroplasty decreases blood use and improves outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(1):11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu D, Dan M, Martinez Martos S, Beller E. Blood management strategies in Total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2016;28(3):179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kimball CC, Nichols CI, Vose JG. Blood transfusion trends in primary and revision Total joint arthroplasty: recent declines are not shared equally. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(20):e920–e927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li J, Li HB, Zhai XC, Qin L, Jiang XQ, Zhang ZH. Topical use of topical fibrin sealant can reduce the need for transfusion, total blood loss and the volume of drainage in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 1489 patients. Int J Surg. 2016;36:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou H, Ge J, Bai Y, Liang C, Yang L. Translation of bone wax and its substitutes: history, clinical status and future directions. J Orthop Transl. 2019;17:64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mortazavi SMJ, Razzaghof M, Ghadimi E, Seyedtabaei SMM, Vahedian Ardakani M, Moharrami A. The efficacy of bone wax in reduction of perioperative blood loss in Total hip arthroplasty via direct anterior approach: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2022;104(20):1805–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moo IH, Chen JYQ, Pagkaliwaga EH, Tan SW, Poon KB. Bone wax is effective in reducing blood loss after Total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(5):1483–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li ZJ, Zhao MW, Zeng L. Additional dose of intravenous Tranexamic acid after primary Total knee arthroplasty further reduces hidden blood loss. Chin Med J. 2018;131(6):638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sehat KR, Evans RL, Newman JH. Hidden blood loss following hip and knee arthroplasty. Correct management of blood loss should take hidden loss into account. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2004;86(4):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gao F, Guo W, Sun W, Li Z, Wang W, Wang B, et al. Correlation between the coverage percentage of prosthesis and postoperative hidden blood loss in primary total knee arthroplasty. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(12):2265–2269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ko PS, Tio MK, Tang YK, Tsang WL, Lam JJ. Sealing the intramedullary femoral canal with autologous bone plug in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(1):6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singla A, Malhotra R, Kumar V, Lekha C, Karthikeyan G, Malik V. A randomized controlled study to compare the Total and hidden blood loss in computer‐assisted surgery and conventional surgical technique of Total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7(2):211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang K, Yuan W, An J, Cheng P, Song P, Li S, et al. Sealing the intramedullary Femoral Canal for blood loss in Total knee arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Knee Surg. 2021;34(2):208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gross JB. Estimating allowable blood loss: corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology. 1983;58(3):277–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nadler SB, Hidalgo JH, Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery. 1962;51(2):224–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Su EP, Su S. Strategies for reducing peri‐operative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt J. 2016;98(1):98–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nogalo C, Meena A, Abermann E, Fink C. Complications and downsides of the robotic total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(3):736–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shin KH, Choe JH, Jang KM, Han SB. Use of bone wax reduces blood loss and transfusion rates after total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2020;27(5):1411–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Demey G, Servien E, Pinaroli A, Lustig S, Aït Si Selmi T, Neyret P. The influence of femoral cementing on perioperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2010;92(3):536–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao HY, Yeersheng R, Kang XW, Xia YY, Kang PD, Wang WJ. The effect of tourniquet uses on total blood loss, early function, and pain after primary total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Bone Jt Res. 2020;9(6):322–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dennis DA, Kittelson AJ, Yang CC, Miner TM, Kim RH, Stevens‐Lapsley JE. Does tourniquet use in TKA affect recovery of lower extremity strength and function? A randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(1):69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stronach BM, Jones RE, Meneghini RM. Tourniquetless total knee arthroplasty: history, controversies, and technique. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang GP, Jia XF, Xiang Z, Ji Y, Wu GY, Tang Y, et al. Tranexamic acid reduces hidden blood loss in patients undergoing Total knee arthroplasty: a comparative study and meta‐analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:797–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bao N, Zhou L, Cong Y, Guo T, Fan W, Chang Z, et al. Free fatty acids are responsible for the hidden blood loss in total hip and knee arthroplasty. Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(1):104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yuan T, Yang S, Lai C, Yu X, Qian H, Meng J, et al. Pathologic mechanism of hidden blood loss after total knee arthroplasty: oxidative stress induced by free fatty acids. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2022;15(3):88–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khanasuk Y, Ngarmukos S, Tanavalee A. Does the intramedullary femoral canal plug reduce blood loss during total knee arthroplasty? Knee Surg Relat Res. 2022;34(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dikmen İ, Kose O, Cakar A, Tasatan E, Ertan MB, Yapar D. Comparison of three methods for sealing of the intramedullary femoral canal during total knee arthroplasty; a randomized controlled trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143(6):3309–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puri S, Chiu YF, Boettner F, Cushner F, Sculco PK, Westrich GH, et al. Avoiding Femoral Canal instrumentation in computer‐assisted Total knee arthroplasty with contemporary blood management had minimal differences in blood loss and transfusion rates compared to conventional techniques. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(7):1278–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao FQ, Li ZJ, Zhang K, Huang D, Liu ZJ. Risk factors for lower limb swelling after primary total knee arthroplasty. Chin Med J. 2011;124(23):3896–3899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Windisch C, Kolb W, Kolb K, Grützner P, Venbrocks R, Anders J. Pneumatic compression with foot pumps facilitates early postoperative mobilisation in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2011;35(7):995–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maradei‐Pereira J, Sauma ML, Demange MK. Thromboprophylaxis with unilateral pneumatic device led to less edema and blood loss compared to enoxaparin after knee arthroplasty: randomized trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seo JG, Moon YW, Park SH, Kim SM, Ko KR. The comparative efficacies of intra‐articular and IV tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(8):1869–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ke C, Tian N, Zhang X, Chen M. Changes in perioperative hemoglobin and hematocrit in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a prospective observational study of optimal timing of measurement. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(11):300060520969303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou Q, Zhou Y, Wu H, Wu Y, Qian Q, Zhao H, et al. Changes of hemoglobin and hematocrit in elderly patients receiving lower joint arthroplasty without allogeneic blood transfusion. Chin Med J. 2015;128(1):75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.