Abstract

Key Points

A negative change in serum sodium during a dialysis session is an independent factor associated with prolonged dialysis recovery time.

Lower hemoglobin is an independent factor associated with fatigue in hemodialysis patients.

Hemodiafiltration use in patients age ≥85 years is associated with a longer dialysis recovery time.

Background

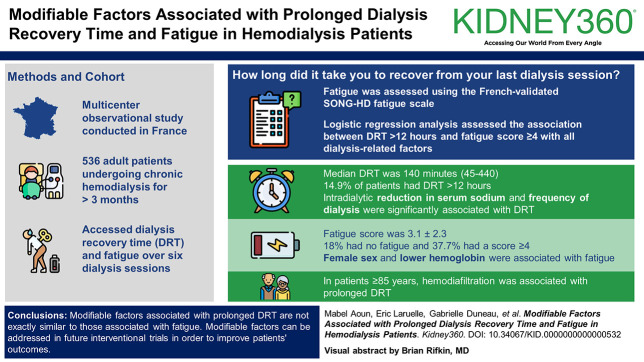

Dialysis recovery time (DRT) and fatigue are two important patient-reported outcomes that highly affect hemodialysis patients' well-being and survival. This study aimed to identify all modifiable dialysis-related factors, associated with DRT and fatigue, that could be addressed in future clinical trials.

Methods

This multicenter observational study included adult patients, undergoing chronic hemodialysis for >3 months during December 2023. Patients admitted to hospital, with cognitive problems or active cancer were excluded. DRT was determined by asking over six sessions: How long did it take you to recover from your last dialysis session? Fatigue was assessed using the French-validated Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis fatigue scale. Logistic regression analysis assessed the association between DRT >12 hours and fatigue score ≥4 with all dialysis-related factors. A subanalysis of DRT-related factors was performed for very elderly patients aged 85 years and above.

Results

A total of 536 patients and 2967 sessions were analyzed. The mean age was 68.1±14.3 years, 60.9% were male, 33.2% had diabetes, and 63.3% were on hemodiafiltration. The median dialysate sodium was 138 (136–140). The median DRT was 140 (45–440) minutes, and 14.9% of patients had DRT >12 hours. Fatigue score was 3.1±2.3, 18% had no fatigue, and 37.7% had a score ≥4. DRT was significantly associated with fatigue score. In multivariable regression analysis, intradialytic reduction in serum sodium and frequency of dialysis were significantly associated with DRT. Factors associated with fatigue included female sex and lower hemoglobin. In patients aged 85 years and above, hemodiafiltration was associated with prolonged DRT.

Conclusions

Modifiable factors associated with prolonged DRT are not exactly similar to those associated with fatigue. Intradialytic reduction in serum sodium and low frequency of dialysis are two independent factors associated with longer DRT, with hemodiafiltration associated with longer recovery in very elderly patients. The hemoglobin level is the modifiable independent factor associated with fatigue. These modifiable factors can be addressed in future interventional trials to improve patients' outcomes.

Keywords: anemia, chronic hemodialysis, hemodialysis adequacy, hyponatremia, patient-centered care, quality of life, sodium (Na+) transport, ultrafiltration

Visual Abstract

Introduction

In 2010, the global scientific community launched the Core Outcomes Effectiveness Trial initiative to establish important outcomes to be studied in clinical trials.1 Following this international call, the nephrology community developed its own standards. The Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) initiative launched a survey among health care providers and patients to prioritize core outcomes to be focused on in hemodialysis patients.2 Fatigue was the most cited along with vascular access problems, cardiovascular disease, and mortality.2 Fatigue is highly prevalent in hemodialysis patients, comparable with patients with malignancy on chemotherapy.3 Fatigue was shown to be highly correlated with pain, depression, and lower socioeconomic status.4 For a long time, a wide range of nonspecific measures were used to assess fatigue in the hemodialysis population.5 In 2020, the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) initiative group developed a short survey for evaluation of fatigue and validated it in 485 patients from the United Kingdom, Australia, and Romania.6 This SONG-HD measure was demonstrated as a reliable measure to be used when studying fatigue in hemodialysis patients. SONG-HD fatigue scale was recently translated and validated in French.7

Dialysis recovery time (DRT) is another important SONG clinical outcome, sometimes called postdialysis fatigue.8 It evaluates the duration of time where patients feel washed out after dialysis sessions. It is assessed using one question.9 The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) working group showed that DRT is associated with lower dialysate sodium, poor quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.10 In 2022, a systematic review from Canada showed a better DRT with medium cutoff (MCO) versus high-flux hemodialysis membranes.11 Ultrafiltration rate and dialysate potassium were also shown to be associated with DRT.12–14 In France, one survey in 2021 assessed electronic patient-reported outcome measures in hemodialysis and found fatigue in 72% of patients.15 All of these studies based their analysis on a one-time DRT question.

The main reason for assessing fatigue and DRT is to find out dialysis-related modifiable factors that could be addressed in clinical trials to improve patients' quality of life and reduce their mortality. So far, very few interventional trials were performed to reduce DRT. A small Canadian trial failed to find an improvement of DRT by using a blood volume monitoring-guided ultrafiltration feedback in 32 randomized patients.16 The Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trials detected shorter recovery times in frequent hemodialysis sessions of six times weekly compared with three times weekly, but these dialysis schedules are not routinely used.17 Large multicenter studies addressing a comprehensive set of potential modifiable factors are still lacking. We hypothesize that factors related to the dialysis session prescription could affect DRT and/or fatigue.

The aim of this study was to identify all available modifiable factors associated with DRT and/or fatigue in hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Study Setting, Population, and Design

This cross-sectional study included all patients undergoing hemodialysis in 14 dialysis units in the North-West of France. Types of hemodialysis offered in these units are (1) in-center hemodialysis providing care for patients whose condition needs the permanent presence of a nephrologist; (2) medicalized dialysis unit three times per week for patients with stable conditions, these patients undergo the conventional thrice weekly sessions of 4 hours or the twice weekly incremental or decremental dialysis; (3) self-care nurse-assisted hemodialysis; (4) nocturnal nurse-assisted hemodialysis three times per week (with sessions of 8 hours); and (5) home hemodialysis.

Data were collected during December 2023 and first week of January 2024.

Eligibility Criteria

Patients age 18 years and older, treated with chronic hemodialysis for at least 3 months, who consented to participate to the study and to respond to the questionnaire of recovery time and fatigue were included. Patients who had cognitive problems, patients with French speaking difficulty, patients with active cancer, and those hospitalized during the study period were excluded.

Outcomes

DRT Assessment

DRT was assessed by asking how long did it take you to recover from your last dialysis session or in French combien de temps vous a-t-il fallu pour récupérer de votre dernière séance d'hémodialyse?7 Nurses asked this question—within December 2023—to each patient at each session for two nonconsecutive weeks in case of thrice weekly hemodialysis and for 3 consecutive weeks in case of twice weekly hemodialysis. Answers were recorded in minutes or hours. Patients who had the same answer for six sessions were considered as having similar or consistent DRT across the six sessions.

Fatigue Assessment

Fatigue was assessed once during the first week of December 2023 by using the French SONG-fatigue validated scale (after authors' approval5). The SONG-HD fatigue scale includes three questions: in the last week, did you feel tired, did you lack energy, and did fatigue limit your usual activities? The response to these questions follows a four-Likert scale: 0=not at all, 1=a little, 2=quite a bit, and 3=severely. The total score of fatigue is defined as the sum of the three scores (0–9).

Variables Collected

Variables collected from electronic medical records included age, sex, weight, body mass index, cause of ESKD, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hepatic disease, pulmonary disease, and cancer), dialysis-related factors including dialysis vintage, type of hemodialysis (day, night, number of weekly sessions, duration of sessions, conventional high-flux hemodialysis, MCO hemodialysis, hemodiafiltration), type and surface of membrane used, blood flow rate, catheter use or arteriovenous fistula, sodium, calcium, bicarbonate and potassium dialysate concentrations, and dialysate type (acetate or hydrochloric acid). We retrieved and calculated the 5-week average (from last week of November 2023 to last week of December 2023) of ultrafiltration rate per kilogram per hour, intradialytic body weight loss (IBWL) defined as the percentage of body weight loss per session, predialysis and postdialysis systolic BP and diastolic BP, and the intradialytic change of systolic BP and diastolic BP (level at the end minus level at the beginning of the dialysis session). The laboratory tests collected were ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, serum albumin, hemoglobin, urea reduction ratio, EqKt/V, serum calcium and phosphate, predialysis and postdialysis serum potassium, sodium, and predialysis serum bicarbonate tested at the beginning of December 2023. We computed as well the intradialytic change in serum sodium defined as postdialysis minus predialysis serum sodium. Medications including darbepoietin, epoetin alfa, epoetin beta, and intravenous iron sucrose were recorded. Weekly doses of erythropoietin-stimulating agents and iron were also collected, and darbepoietin dose was converted to international unit by multiplying by 200 every µg.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as means and SD if their distribution was normal and as medians and interquartile range if the distribution was asymmetrical. Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. DRT was categorized as <2 hours (120 minutes), 120–360 minutes, 361–720 minutes, and >12 hours (720 minutes). Patients with very prolonged DRT >12 hours were mainly addressed in the analysis. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess factors associated with DRT >12 hours and with a fatigue score ≥4. Multivariable regression analysis included all variables found statistically significant in univariate analysis or known to be confounders in the literature. SPSS version 25.0 was used to analyze data. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Inclusion of Patients

A total of 716 adult patients, on hemodialysis for at least 3 months, were screened. One hundred and eighty were excluded: 85 for either cognitive impairment or French speaking difficulty, ten for active cancer, 51 refused to participate, and 34 were admitted to hospital. Finally, 536 patients were included: 152 patients from five units in Rennes, 125 patients from three units in Lorient, 98 patients from one unit in Saint-Malo, 52 patients from one unit in Saint-Brieuc, 43 patients from one unit in Avranches, 30 patients from one unit in Pontivy, 26 patients from one unit in Quimper, and ten patients from one unit in Brest.

General Characteristics of Patients

A total of 536 patients and 2967 sessions were finally included and analyzed. Table 1 summarizes their characteristics. Their mean age was 68.1±14.3 years with 10.4% ≥85 years, and 60.9% were male. Their median dialysis vintage was 41 (22.5–80) months, 63.3% were on hemodiafiltration, and 16.2% were on twice weekly dialysis. Patients who were on twice weekly hemodialysis had a median dialysis vintage of 25 (12–43) months, and those with higher frequency of dialysis had a median dialysis vintage of 46 (26–86) months (P < 0.001). IBWL was 2.5%±1.2% in the whole sample, 1.7%±1.5% in patients on twice weekly hemodialysis, and 2.7%±1.1% in those with more frequent hemodialysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Variable | Total Sample N=536 |

|---|---|

| Demographics and comorbidities | |

| Age in yr, mean±SD | 68.1±14.3 |

| Min–max | 18–93 |

| <60 | 144 (26.9) |

| 60–80 | 137 (62.9) |

| ≥85 | 55 (10.3) |

| Sex (M/F), No. (%) | 327/209 (61/39) |

| Dialysis vintage in mo, median (IQR) | 41 (22.3–80) |

| Weight in kg, mean±SD | 75.2±19.4 |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean±SD | 26.6±6.1 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 178 (33.2) |

| CVD, No. (%) | 248 (46.3) |

| No. of comorbidities, mean±SD | 2.6±2.3 |

| Cause of kidney disease, No. (%) | |

| Nephrosclerosis | 111 (20.7) |

| Diabetes | 103 (19.2) |

| Glomerular disease | 72 (13.4) |

| ADPKD | 60 (11.2) |

| Undetermined | 38 (7.1) |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 57 (10.6) |

| Other | 50 (9.3) |

| Dialysis prescription | |

| Session schedule | |

| Day | 508 (94.8) |

| Nocturnal | 28 (5.2) |

| Frequency per week, No. (%) | |

| Thrice weekly | 440 (82.1) |

| Twice weekly | 87 (16.2) |

| Four times weekly | 6 (1.1) |

| Five days per week | 3 (0.6) |

| Session duration in min, median (IQR) | 240 (210–240) |

| Vascular access, No. (%) | |

| AVF | 457 (85.3) |

| Gore-tex | 2 (0.4) |

| Tunneled catheter | 77 (14.4) |

| Left side | 366 (68.3) |

| Right side | 170 (31.7) |

| Hemodialysis technique, No. (%) | |

| Hemodiafiltration postdilutional | 322 (60.1) |

| Hemodiafiltration predilutional | 17 (3.2) |

| Conventional hemodialysis | 197 (36.8) |

| Membrane used, No. (%) | |

| Polynephron (PES) | 305 (56.9) |

| Purema (high-flux PES) | 101 (18.8) |

| MCO | 44 (8.2) |

| NF (high-flux PMMA) | 40 (7.5) |

| Others | 46 (8.6) |

| Membrane surface in m2, mean±SD | 2.2±0.2 |

| Blood flow rate, ml/min, median (IQR) | 350 (350–400) |

| Dialysate sodium, median (IQR) | 138 (136–140) |

| Min–max | 130–142 |

| Dialysate sodium <136, No. (%) | 150 (28) |

| Dialysate potassium, No. (%) | |

| K=2 mmoL/L | 279 (52.1) |

| K=3 mmoL/L | 257 (47.9) |

| Dialysate bicarbonate, median (IQR) | 34 (33–35) |

| Min–max | 28–39 |

| Dialysate calcium, No. (%) | |

| Ca=1.25 mmoL/L | 24 (4.5) |

| Ca=1.5 mmoL/L | 391 (72.9) |

| Ca=1.75 mmoL/L | 121 (22.6) |

| Dialysate type, No. (%) | |

| HCL | 386 (72) |

| Acetate | 150 (28) |

| Average ultrafiltration and BP over 5 wk | |

| Ultrafiltration per session in liters | 1.9±0.9 |

| Ultrafiltration in ml/kg per hour | 6.4±3.2 |

| Min–max | 0–22.6 |

| IBWL in kg % | 2.5±1.2 |

| Predialysis SBP, mm Hg | 139±18.7 |

| Postdialysis SBP, mm Hg | 137.4±22.4 |

| Intradialytic change in SBP, mm Hg | −1.5±17.3 |

| Predialysis DBP | 70.2±11.9 |

| Postdialysis DBP, mm Hg | 69.6±12.4 |

| Intradialytic change in DBP, mm Hg | −0.6±8.1 |

| Last blood tests | |

| EqKt/V | 1.5±0.3 |

| Hemoglobin in g/dl | 11.5±1.1 |

| Ferritin in ng/ml | 372 (218–522) |

| PTH in pg/ml | 214 (114–373) |

| 25-hydroxy vitamin D in ng/ml | 86.5±29.7 |

| Calcium in mmoL/L | 2.2±0.2 |

| Phosphate in mmoL/L | 1.5±0.5 |

| Predialysis serum sodium in mmoL/L | 137±3.4 |

| Postdialysis serum sodium in mmoL/L | 136.7±2.7 |

| Intradialytic change in serum sodium (postdialysis minus predialysis) | −0.23±2.7 |

| Predialysis serum potassium in mmoL/L | 4.7±0.6 |

| Postdialysis serum potassium in mmoL/L | 3.6±0.4 |

| Predialysis serum bicarbonate in mmoL/L | 22.6±2.6 |

| Serum albumin in g/L | 36.9±4.8 |

| CRP in mg/L | 5 (4–10.1) |

| Anemia medications | |

| ESA dose in UI/kg per week | 87.3±92.6 |

| Iron dose in mg/wk | 50.2±47.9 |

Continuous variables are expressed as means and SD if they have normal distribution and medians and interquartile range if otherwise. Categorical variables are reported as numbers and percentages. AVF, arteriovenous fistula; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic BP; ESA, erythropoietin-stimulating agent; HCL, hydrochloric acid; IBWL, intradialytic body weight loss; IQR, interquartile range; MCO, medium cutoff; PES, polyethylsulfone; PMMA, polymethylmethacrylate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SBP, systolic BP; UI, international unit.

Six comorbidities were assessed (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hepatic disease, pulmonary disease, and cancer).

DRT and Fatigue Score

The median DRT was 140 (45–440) minutes and the mean SONG-HD fatigue total score was 3.1±2.3 with 18% having no fatigue (Table 2). Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 illustrate all characteristics of patients across different DRT categories and fatigue score. DRT and fatigue score were significantly associated (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Dialysis recovery time and fatigue

| Variable | Total Sample N=536 |

|---|---|

| DRT | |

| DRT in minutes, median (IQR) | 140 (45–440) |

| DRT by categories, min, No. (%) | |

| 0 | 75 (14) |

| <120 | 229 (42.7) |

| 120–360 | 87 (16.2) |

| 361–720 | 140 (26.1) |

| >720 | 80 (14.9) |

| Similar DRT across six sessions, No. (%) | 252 (47) |

| Fatigue | |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score (0–9), mean±SD | 3.1±2.3 |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score ≥4, No. (%) | 202 (37.7) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=0 | 95 (18) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=1 | 56 (10.6) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=2 | 84 (15.9) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=3 | 91 (17.2) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=4 | 59 (11.2) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=5 | 49 (9.3) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=6 | 55 (10.4) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=7 | 18 (3.4) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=8 | 7 (1.3) |

| SONG-HD fatigue total score=9 | 14 (2.7) |

DRT, dialysis recovery time; IQR, interquartile range; SONG-HD, Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis.

Figure 1.

Relationship between SONG-HD fatigue score and different categories of DRT. DRT, dialysis recovery time; SONG-HD, Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis.

Factors Associated with DRT

Using the univariate logistic regression analysis, age, catheter use, low dialysate sodium, twice weekly dialysis, and negative intradialytic change in serum sodium were associated with DRT >12 hours (shown in Figure 2 and Table 3).

Figure 2.

Relationship between DRT and the change in serum sodium levels (postdialysis minus predialysis).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with dialysis recovery time >12 hours

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age, yr | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.04 | 0.061 | |||

| Age by categories (ref <60 yr), yr | ||||||

| 60–84 | 0.65 | 0.38 to 1.14 | 0.131 | 0.52 | 0.29 to 0.95 | 0.035 |

| ≥85 | 2.24 | 1.09 to 4.59 | 0.029 | 1.98 | 0.93 to 4.25 | 0.078 |

| Sex (ref. male) | 1.19 | 0.73 to 1.92 | 0.486 | 1.01 | 0.61 to 1.69 | 0.957 |

| Dialysis vintage | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.002 | 0.523 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.977 |

| Diabetes | 0.96 | 0.58 to 1.59 | 0.884 | 0.90 | 0.53 to 1.53 | 0.699 |

| BMI | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.06 | 0.347 | |||

| CVD | 1.11 | 0.69 to 1.78 | 0.678 | |||

| Dialysis ≥thrice weekly (ref. twice weekly) | 0.52 | 0.29 to 0.91 | 0.023 | 0.50 | 0.28 to 0.92 | 0.026 |

| Duration of session | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.001 | 0.140 | |||

| Nocturnal dialysis (ref. day dialysis) | 0.95 | 0.32 to 2.81 | 0.922 | |||

| Catheter use (ref. AVF) | 2.33 | 1.31 to 4.16 | 0.004 | 1.74 | 0.93 to 3.25 | 0.081 |

| Ultrafiltration ml/kg per hour | 0.97 | 0.89 to 1.04 | 0.392 | |||

| Hemodiafiltration (ref. conventional hemodialysis) | 1.64 | 0.97 to 2.78 | 0.065 | |||

| Blood flow | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.275 | |||

| Dialysate sodium | 0.89 | 0.79 to 0.99 | 0.029 | 0.93 | 0.80 to 1.08 | 0.333 |

| Predialysis serum sodium | 1.01 | 0.94 to 1.08 | 0.853 | |||

| Postdialysis serum sodium | 0.89 | 0.82 to 0.98 | 0.012 | 0.96 | 0.85 to 1.08 | 0.450 |

| Intradialytic change in serum sodium | 0.87 | 0.79 to 0.96 | 0.004 | 0.89 | 0.81 to 0.98 | 0.021 |

| Membrane surface | 0.86 | 0.32 to 2.33 | 0.765 | |||

| MCO (ref. all other membranes) | 0.89 | 0.36 to 2.18 | 0.802 | |||

| Acetate dialysate (ref. HCL) | 0.97 | 0.57 to 1.65 | 0.917 | |||

| Dialysate bicarbonate | 1.01 | 0.87 to 1.18 | 0.874 | |||

| Predialysis serum potassium | 1.07 | 0.73 to 1.58 | 0.717 | |||

| Postdialysis serum potassium | 0.97 | 0.52 to 1.79 | 0.926 | |||

| Intradialytic change in serum potassium | 1.09 | 0.73 to 1.65 | 0.670 | |||

| Potassium dialysate (ref. K=2) | 1.24 | 0.77 to 1.99 | 0.377 | |||

| Calcium dialysate (ref. Ca=1.25) | 0.65 | 0.19 to 2.19 | 0.492 | |||

| Kt/V | 0.79 | 0.38 to 1.68 | 0.555 | |||

| Hemoglobin | 0.91 | 0.74 to 1.12 | 0.368 | |||

| Serum albumin | 0.97 | 0.92 to 1.02 | 0.211 | |||

| CRP level | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.938 | |||

| Serum phosphate | 0.81 | 0.49 to 1.35 | 0.417 | |||

| PTH level | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.228 | |||

| Predialysis SBP | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.900 | |||

| Postdialysis SBP | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.475 | |||

| Intradialytic change in SBP | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.395 | |||

| Predialysis DBP | 1.001 | 0.98 to 1.02 | 0.941 | |||

| Postdialysis DBP | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.01 | 0.511 | |||

| Intradialytic change in DBP | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.01 | 0.267 | |||

| SONG-HD fatigue total score | 1.41 | 1.26 to 1.57 | <0.001 | |||

The multivariable analysis included all variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis except for the fatigue score. Eighty patients had a dialysis recovery time >12 hours. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic BP; HCL, hydrochloric acid; MCO, medium cutoff; OR, odds ratio; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SBP, systolic BP; SONG-HD, Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis.

In the multivariable analysis, intradialytic change in serum sodium and the frequency of dialysis per week were the two factors that remained significantly associated with DRT >12 hours (Table 3).

Factors Associated with Fatigue

Using the univariate logistic regression analysis, factors associated with a fatigue score ≥4 were being a women, session duration, dialysate sodium, and hemoglobin level (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis fatigue total score ≥4

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age | 1.004 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.532 | ||||||

| Age categories (ref <60 yr), yr | |||||||||

| 60–84 | 0.76 | 0.51 to 1.13 | 0.177 | 0.59 | 0.38 to 0.93 | 0.023 | 0.65 | 0.42 to 1.00 | 0.051 |

| ≥85 | 1.78 | 0.95 to 3.33 | 0.071 | 1.43 | 0.73 to 2.78 | 0.295 | 1.57 | 0.79 to 3.09 | 0.194 |

| Sex (ref. male) | 1.89 | 1.32 to 2.70 | <0.001 | 1.73 | 1.20 to 2.51 | 0.004 | 1.87 | 1.26 to 2.77 | 0.002 |

| Dialysis vintage | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.849 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.941 | |||

| Diabetes | 1.03 | 0.71 to 1.49 | 0.862 | 1.05 | 0.71 to 1.55 | 0.826 | |||

| BMI | 1.001 | 0.97 to 1.03 | 0.922 | ||||||

| CVD | 1.09 | 0.77 to 1.55 | 0.620 | ||||||

| Dialysis ≥thrice weekly (ref. twice weekly) | 1.61 | 0.98 to 2.66 | 0.061 | ||||||

| Duration of session | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.029 | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.145 | |||

| Nocturnal dialysis (ref. day dialysis) | 0.54 | 0.22 to 1.28 | 0.161 | ||||||

| Catheter use (ref. AVF) | 1.29 | 0.79 to 2.10 | 0.312 | ||||||

| Ultrafiltration ml/kg per hour | 0.98 | 0.93 to 1.04 | 0.550 | ||||||

| Hemodiafiltration (ref. conventional hemodialysis) | 1.24 | 0.86 to 1.79 | 0.249 | ||||||

| Blood flow | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.348 | ||||||

| Dialysate sodium | 0.91 | 0.83 to 0.99 | 0.021 | 0.92 | 0.84 to 0.99 | 0.048 | |||

| Predialysis serum sodium | 0.99 | 0.95 to 1.05 | 0.907 | ||||||

| Postdialysis serum sodium | 0.97 | 0.91 to 1.03 | 0.295 | ||||||

| Change in serum sodium, post-pre | 0.97 | 0.91 to 1.03 | 0.320 | ||||||

| Membrane surface | 0.81 | 0.39 to 1.67 | 0.555 | ||||||

| MCO membrane (ref. all membranes) | 1.28 | 0.69 to 2.39 | 0.433 | ||||||

| Acetate dialysate (ref. HCL) | 0.80 | 0.54 to 1.19 | 0.273 | ||||||

| Dialysate bicarbonate | 0.99 | 0.89 to 1.11 | 0.926 | ||||||

| Predialysis serum potassium | 1.09 | 0.83 to 1.46 | 0.527 | ||||||

| Postdialysis serum potassium | 1.11 | 0.71 to 1.75 | 0.648 | ||||||

| Intradialytic change in serum potassium | 1.08 | 0.79 to 1.47 | 0.617 | ||||||

| Potassium dialysate (ref. K=2) | 1.11 | 0.78 to 1.57 | 0.575 | ||||||

| Calcium dialysate (ref. Ca=1.25) | 2.60 | 0.95 to 7.12 | 0.062 | ||||||

| Kt/V | 1.55 | 0.89 to 2.67 | 0.116 | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 0.80 | 0.69 to 0.94 | 0.006 | 0.83 | 0.70 to 0.98 | 0.023 | 0.83 | 0.70 to 0.99 | 0.040 |

| Ferritin | 1.00 | 0.99,1.00 | 0.831 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.779 | |||

| Serum albumin | 0.96 | 0.93 to 1.00 | 0.055 | 0.98 | 0.94 to 1.02 | 0.375 | |||

| Serum phosphate | 0.83 | 0.58 to 1.20 | 0.332 | ||||||

| CRP level | 1.003 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.454 | 1.003 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.402 | |||

| PTH level | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.747 | ||||||

| Predialysis SBP | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.874 | ||||||

| Postdialysis SBP | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.692 | ||||||

| Intradialytic change in SBP | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.697 | ||||||

| Predialysis DBP | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.703 | ||||||

| Postdialysis SBP | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.408 | ||||||

| Intradialytic change in DBP | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.01 | 0.434 | ||||||

| Dose of ESA | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.587 | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.483 | |||

| Dose of iron | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.213 | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.412 | |||

| DRT | 1.001 | 1.001 to 1.002 | <0.001 | ||||||

Model 1 included age categories, sex, dialysis vintage, diabetes, and all variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis except for the dialysis recovery time. Model 2 included age categories, sex, and all variables that might affect hemoglobin: C-reactive protein, serum albumin, ferritin, iron dose, erythropoietin-stimulating agent dose. Two hundred two patients had a Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis fatigue score ≥4. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic BP; DRT, dialysis recovery time; ESA, erythropoietin-stimulating agent; HCL, hydrochloric acid; MCO, medium cutoff; OR, odds ratio; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SBP, systolic BP.

In the multivariable regression analysis (Table 4), two factors remained associated with a fatigue score ≥4: being a women and lower hemoglobin. The mean hemoglobin in the group with a fatigue score ≥4 was 11.3±1.1 g/dl versus 11.6±1.1 in patients with lower scores. In a model that adjusted hemoglobin for age, sex, CRP, ferritin, serum albumin, erythropoietin-stimulating agent dose, and iron dose, the association of hemoglobin with fatigue score ≥4 became less significant (odds ratio=0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70 to 0.99; P = 0.040).

Subanalysis of Very Elderly Patients

In the subgroup of patients age ≥85 years (Table 5), hemodiafiltration was associated with prolonged DRT, and lower hemoglobin was associated with fatigue.

Table 5.

Subanalysis of the very elderly group, ≥85 years

| Variable | DRT >12 h | Total Fatigue Score ≥4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Sex. ref. male | 0.42 | 0.12 to 1.41 | 0.160 | 1.31 | 0.45 to 3.84 | 0.620 |

| Dialysis vintage | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.775 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | 0.696 |

| Catheter use | 1.14 | 0.25 to 5.23 | 0.863 | 0.61 | 0.15 to 2.59 | 0.508 |

| Hemodiafiltration ref. conventional hemodialysis | 4.2 | 1.04 to 17.03 | 0.045 | 1.57 | 0.53 to 4.69 | 0.419 |

| Intradialytic change in serum sodium | 0.96 | 0.79 to 1.17 | 0.676 | 1.17 | 0.96 to 1.43 | 0.125 |

| Dialysate sodium | 0.91 | 0.72 to 1.16 | 0.464 | 0.98 | 0.78 to 1.22 | 0.835 |

| Duration of session | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.04 | 0.287 | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.02 | 0.715 |

| Intradialytic body weight loss | 1.05 | 0.58 to 1.91 | 0.866 | 0.92 | 0.52 to 1.59 | 0.753 |

| Hemoglobin level | 0.97 | 0.55 to 1.72 | 0.926 | 0.51 | 0.28 to 0.93 | 0.029 |

Univariate logistic regression analysis of factors was performed for both dependent variables. In a model 1 adjusting for intradialytic body weight loss, hemodiafiltration was associated with dialysis recovery time (odds ratio=4.1; 95% confidence interval, 0.99 to 17.13; P = 0.05). In a model 2 adjusting for body mass index, hemodiafiltration was less associated with dialysis recovery time (odds ratio=3.9; 95% confidence interval, 0.96 to 15.9; P = 0.058). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; DRT, dialysis recovery time; OR, odds ratio.

Fifty-five patients were age 85 years and above.

Discussion

This study identified several modifiable factors that could be possibly associated with prolonged DRT and/or fatigue. The main factors found to be associated with prolonged recovery time are the intradialytic reduction in serum sodium and the lower frequency of weekly dialysis sessions. On the other hand, the major modifiable factor that showed association with fatigue is the hemoglobin level.

Our findings revealed a prolonged DRT above 12 hours in 15% of patients, and this was strongly associated with an intradialytic reduction in serum sodium. The largest prospective study that previously evaluated DRT is the DOPPS study that included 6040 patients from 12 countries in 2014.10 The DOPPS study evaluated DRT as four categories, found a DRT >12 hours in 10% of patients, and it did not analyze many laboratory variables such as serum sodium, potassium, or bicarbonate. It focused mainly on dialysis technique and dialysate parameters and showed that a dialysate sodium level <140 mmoL/L, compared with 140 mmoL/L, leads to prolonged DRT. In our cohort, the dialysate sodium was significantly associated with DRT, but, after adjustment to serum sodium, this association was lost, and the intradialytic change in serum sodium remained an independent risk factor. Other studies followed the DOPPS, some found an association with DRT,18 and some did not,13,19 but none of them evaluated the change in intradialytic serum sodium.

The trend to avoid increasing serum sodium during a dialysis session emerged with the rationale that a lower dialysate sodium decreases interdialytic weight gain,20 reduces hypertension, and lowers mortality.21 Excessively increasing serum sodium concentration (>4 mmoL/L) compared with <2 mmoL/L during a dialysis session was also demonstrated as a predictor for higher mortality.22 All this evidence led nephrologists to attempt isonatric hemodialysis or to use lower dialysate sodium,23 which probably led to an intradialytic reduction in serum sodium. However, the lower dialysate sodium did not reduce left ventricular mass,20 and a recent population study showed that a dialysate sodium level below 138 mmoL/L is associated with higher mortality.24 These recent findings concur well with our results knowing that prolonged DRT is associated with mortality. Thus, a more individualized prescription of dialysate sodium that considers DRT along with the weight gain and the BP seems to be necessary.

Surprisingly, we did not find any effect of ultrafiltration or IBWL on DRT. The DOPPS study showed a positive association between these two factors,10 but the mean IBWL in DOPPS was 3.12%, whereas it was 2.5% in our sample. The percentage of patients in DOPPS with ultrafiltration >15 ml/min was 10%. On the contrary, only 1.5% of our patients had a mean ultrafiltration above 15 ml/kg per hour. In fact, as a good clinical practice in the past decade, dialysis facilities are avoiding high ultrafiltration rates.25 This could be the reason for the lack of association between this parameter and DRT in our patients. Similar to the ultrafiltration rate, the intradialytic change in BP is not associated with DRT in our patients. However, several previous studies suggested that intradialytic hypotension or ultrafiltration rates might be associated with recovery time.10,12,13,26 The median DRT in some of these studies ranged between 180 and 300 minutes. The median DRT in our patients was 140 minutes, and to our knowledge, this is the shortest median time reported among recovery time studies, which could be probably due to the fact that high ultrafiltration rates were mostly avoided or because our patients had preserved residual diuresis.

It is noteworthy that some variables collected and analyzed in our study did not vary significantly between patients. This narrow range of variation may have prevented finding an association with the DRT and fatigue outcomes. The blood flow rate and the session duration are two examples of factors that had limited variation range.

Interestingly, twice weekly dialysis compared with thrice weekly is found in our study as an independent factor associated with prolonged DRT. This is in accordance with the concept that more frequent hemodialysis is better. The Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trials detected lower DRT in six times weekly dialysis compared with thrice weekly, whether daily or nocturnal.17 However, patients included in our study on twice weekly are most on incremental dialysis, with higher residual diuresis and are expected to have lower DRT. In fact, a previous study found lower DRT in patients on incremental dialysis, but they did not adjust for dialysis vintage.27

Another interesting finding is the association of hemodiafiltration with prolonged DRT in our very elderly patients age ≥85 years. Our cohort included 63% of patients treated with hemodiafiltration, and their mean age was 68 years. This is the higher mean age among all studies that assessed hemodiafiltration versus conventional high-flux dialysis.28 DOPPS included patients with a mean age of 64.8 years,10 and the CONVINCE trial had a mean age of 62 years and did not report specifically DRT.29 On the other hand, a meta-analysis comparing hemodiafiltration to MCO dialysis showed shorter DRT with the MCO membranes.11 In our patients, MCO did not affect DRT, but the number of patients treated with MCO membrane was too small to draw a solid conclusion. To our knowledge, no previous study assessed the impact of hemodiafiltration in very elderly patients and this research question should be addressed in future trials.

Finally, the fatigue score in our study was found to be 3.1, the lowest reported. In 2020, the SONG-HD measure revealed a score of 5.2 in the United Kingdom, 4.3 in Australia, and 3.8 in Romania.6 The low score of fatigue despite the older age of our patients is surprising. On the other hand, fatigue was significantly associated with anemia in our study. A previous smaller French cohort including 173 patients with a mean age of 66.2 years did not find an association between fatigue and anemia, but they did not use the SONG fatigue scale.15 Correlation between fatigue/quality of life and anemia is inconsistent in the literature, especially when targeting high hemoglobin levels like in the CHOIR and CREATE trials.30,31 The mean hemoglobin in our patients was 11.6 g/dl in those with lower fatigue scores versus 11.3 g/dl in those with a score ≥4. Several factors play a role in the association between anemia and fatigue. In the model that adjusted for sex, serum albumin, and CRP, the association between hemoglobin and fatigue became less significant (P = 0.05). It is worth emphasizing that being a woman is an important factor related to fatigue in our sample. While sex is typically regarded as a nonmodifiable factor, the approach to caring for women may require adjustment, given the likelihood of weaker muscles in comparison with men.

This study has many strengths. Its multicenter design helped assessing all possible modifiable dialysis-related factors. It has no missing data. It includes laboratory data that helped reduce confounding by indication regarding dialysate prescriptions. And most of all, the methodology used to assess DRT included the average of six sessions unlike previous studies that drew conclusions based on a one-time question; in fact, only 47% of our patients replied to the DRT question similarly and consistently throughout the six sessions.

On the other hand, this study has some limitations related to its relatively small sample size, its observational design, and multiple testing. In addition, it might have missed some potential unmeasured confounding variables associated with specific facility practices. It did not collect data on residual diuresis, blood volume monitoring sessions, and medications such as diuretics, antihypertensive medications, anxiolytics, or antidepressants. It has also a small group of very elderly patients that preclude from drawing strong conclusions regarding hemodiafiltration in this subgroup. Finally, the characteristics of our sample with high percentage of arteriovenous fistula and high Kt/V might preclude from generalizing our results to other, noncomparable populations.

In conclusion, dialysis-related modifiable factors associated with prolonged DRT are not exactly similar to those associated with fatigue. Intradialytic reduction of serum sodium and twice weekly dialysis are two independent factors associated with longer DRT, with hemodiafiltration associated with longer recovery in very elderly patients, whereas the modifiable independent factor associated with more fatigue is the low hemoglobin level. These factors need to be addressed in future clinical trials to assess their impact on reducing recovery time and fatigue in the hemodialysis population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mrs. Gaëlle Durocher, Mrs. Romina Aguilar, Mr. Alain Tehery, and all nurses of the 14 dialysis units in Brittany and Normandy who helped with the data collection. We are also very grateful to all patients who participated to this study.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Dialysis Recovery Time—Can We Do Better?,” on pages 1235–1237.

Disclosures

Disclosure forms, as provided by each author, are available with the online version of the article at http://links.lww.com/KN9/A615.

Funding

None.

Statement of Ethics

The study got the approval of the institutional ethics committee (CLE-GHBS-23-07), and it was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Mabel Aoun.

Data curation: Mabel Aoun, Simon Duquennoy, Céline Bellier, Claire Cain, Pauline Colin, Sandrine Fleury, Christel Floch, Marion Gritti, Juliette Hervé, Eric Laruelle, Thibault Dolley-Hitze.

Formal analysis: Mabel Aoun, Bruno Legendre.

Investigation: Mabel Aoun, Simona Baluta, Gabrielle Duneau, Simon Duquennoy, Morgane Gosselin, Aldjia Lamri, Eric Laruelle, Thérèse Maroun.

Methodology: Mabel Aoun, Thibault Dolley-Hitze.

Project administration: Mabel Aoun.

Resources: Mabel Aoun, Juliette Baleynaud, Simona Baluta, Céline Bellier, Claire Cain, Béatrice Champtiaux-Dechamps, Jonathan Chemouny, Pauline Colin, Thibault Dolley-Hitze, Gabrielle Duneau, Simon Duquennoy, Sandrine Fleury, Christel Floch, Morgane Gosselin, Marion Gritti, Juliette Hervé, Philippe Jousset, Aldjia Lamri, Eric Laruelle, Lionel Le Mouellic, Thérèse Maroun.

Software: Mabel Aoun.

Supervision: Mabel Aoun.

Validation: Mabel Aoun, Thibault Dolley-Hitze, Eric Laruelle.

Visualization: Mabel Aoun, Thibault Dolley-Hitze, Bruno Legendre.

Writing – original draft: Mabel Aoun.

Writing – review & editing: Mabel Aoun, Juliette Baleynaud, Simona Baluta, Céline Bellier, Claire Cain, Béatrice Champtiaux-Dechamps, Pauline Colin, Thibault Dolley-Hitze, Gabrielle Duneau, Simon Duquennoy, Sandrine Fleury, Christel Floch, Morgane Gosselin, Marion Gritti, Juliette Hervé, Philippe Jousset, Aldjia Lamri, Eric Laruelle, Lionel Le Mouellic, Bruno Legendre, Thérèse Maroun.

Data Sharing Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/KN9/A616.

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients (comparing different categories of DRT).

Supplemental Table 2. Baseline characteristics of patients (comparing different categories of fatigue score).

References

- 1.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Gargon E. The COMET (core outcome measures in effectiveness trials) initiative. Trials. 2011;12(S1):A70. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-S1-A70 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evangelidis N Tong A Manns B, et al. Developing a set of core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: an international Delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(4):464–475. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Sandwijk MS Al Arashi D van de Hare FM, et al. Fatigue, anxiety, depression and quality of life in kidney transplant recipients, haemodialysis patients, patients with a haematological malignancy and healthy controls. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(5):833–838. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devaraj SM Roumelioti ME Yabes JG, et al. Correlates of rates and treatment readiness for depressive symptoms, pain, and fatigue in hemodialysis patients: results from the TĀCcare study. Kidney360. 2023;4(9):e1265–e1275. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000000000000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ju A Unruh ML Davison SN, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(3):327–343. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju A Teixeira-Pinto A Tong A, et al. Validation of a core patient-reported outcome measure for fatigue in patients receiving hemodialysis: the SONG-HD fatigue instrument. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(11):1614–1621. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05880420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mainguy A Ju A Tong A, et al. Validation de l’échelle SONG-Fatigue en Français. Nephrol Ther. 2022;18(5):306–307. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2022.07.235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bossola M, Hedayati SS, Brys ADH, Gregg LP. Fatigue in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;82(4):464–480. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindsay RM, Heidenheim PA, Nesrallah G, Garg AX, Suri R.; Daily Hemodialysis Study Group London Health Sciences Centre. Minutes to recovery after a hemodialysis session: a simple health-related quality of life question that is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):952–959. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00040106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rayner HC Zepel L Fuller DS, et al. Recovery time, quality of life, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(1):86–94. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandi M, Brignardello-Petersen R, Couban R, Wu C, Nesrallah G. Clinical outcomes with Medium cut-off versus high-flux hemodialysis membranes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022;9:20543581211067087. doi: 10.1177/20543581211067087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussein WF, Arramreddy R, Sun SJ, Reiterman M, Schiller B. Higher ultrafiltration rate is associated with longer dialysis recovery time in patients undergoing conventional hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46(1):3–10. doi: 10.1159/000476076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossola M Di Stasio E Monteburini T, et al. Recovery time after hemodialysis is inversely associated with the ultrafiltration rate. Blood Purif. 2019;47(1-3):45–51. doi: 10.1159/000492919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harford A Gul A Cumber S, et al. Low dialysate potassium concentration is associated with prolonged recovery time. Hemodial Int. 2017;21(suppl 2):S27–S32. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerraoui A Prezelin-Reydit M Kolko A, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in hemodialysis patients: results of the first multicenter cross-sectional ePROMs study in France. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):357. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02551-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung KCW, Quinn RR, Ravani P, Duff H, MacRae JM. Randomized crossover trial of blood volume monitoring-guided ultrafiltration biofeedback to reduce intradialytic hypotensive episodes with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1831–1840. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01030117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg AX Suri RS Eggers P, et al. Patients receiving frequent hemodialysis have better health-related quality of life compared to patients receiving conventional hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2017;91(3):746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsayed MM, Zeid MM, Hamza OMR, Elkholy NM. Dialysis recovery time: associated factors and its association with quality of life of hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):298. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02926-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossola M Di Stasio E Monteburini T, et al. Intensity, duration, and frequency of post-dialysis fatigue in patients on chronic haemodialysis. J Ren Care. 2020;46(2):115–123. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall MR Vandal AC de Zoysa JR, et al. Effect of low-sodium versus conventional sodium dialysate on left ventricular mass in home and self-care satellite facility hemodialysis patients: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(5):1078–1091. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019090877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecking M Karaboyas A Saran R, et al. Predialysis serum sodium level, dialysate sodium, and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):238–248. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujisaki K Joki N Tanaka S, et al. Pre-dialysis hyponatremia and change in serum sodium concentration during a dialysis session are significant predictors of mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(2):342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall MR, Karaboyas A. Temporal changes in dialysate [Na+] prescription from 1996 to 2018 and their clinical significance as judged from a meta-regression of clinical trials. Semin Dial. 2020;33(5):372–381. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinter J Smyth B Stuard S, et al. Effect of dialysate and plasma sodium on mortality in a global historical hemodialysis cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024;35(2):167–176. doi: 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Assimon MM, Wenger JB, Wang L, Flythe JE. Ultrafiltration rate and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(6):911–922. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozen N, Cepken T, Tosun B. Do biochemical parameters and intradialytic symptoms affect post-dialysis recovery time? A prospective, descriptive study. Ther Apher Dial. 2021;25(6):899–907. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.13624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davenport A Guirguis A Almond M, et al. Comparison of characteristics of centers practicing incremental vs. conventional approaches to hemodialysis delivery - postdialysis recovery time and patient survival. Hemodial Int. 2019;23(3):288–296. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bossola M Monteburini T Parodi E, et al. Post-dialysis fatigue: comparison of bicarbonate hemodialysis and online hemodiafiltration. Hemodial Int. 2023;27(1):55–61. doi: 10.1111/hdi.13058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blankestijn PJ Vernooij RWM Hockham C, et al. Effect of hemodiafiltration or hemodialysis on mortality in kidney failure. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(8):700–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2304820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh AK Szczech L Tang KL, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drüeke TB Locatelli F Clyne N, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2071–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. All data are included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.