Abstract

With breast cancer emerging as a pressing global health challenge, characterized by escalating incidence rates and geographical disparities, there is a critical need for innovative therapeutic strategies. This comprehensive research navigates the landscape of nanomedicine, specifically focusing on the potential of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), with magnetite (Fe3O4) taking center stage. MNPs, encapsulated in biocompatible polymers like silica known as magnetic silica nanoparticles (MSN), are augmented with phosphotungstate (PTA) for enhanced chemodynamic therapy (CDT). PTA is recognized for its dual role as a natural chelator and electron shuttle, expediting electron transfer from ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+) ions within nanoparticles. Additionally, protein-based charge-reversal nanocarriers like silk sericin and gluten are introduced to encapsulate (MSN-PTA) nanoparticles, offering a dynamic facet to drug delivery systems for potential revolutionization of breast cancer therapy. This study successfully formulates and characterizes protein-coated nanocapsules, specifically MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU, with optimal physicochemical attributes for drug delivery applications. The careful optimization of sericin and gluten concentrations results in finely tuned nanoparticles, showcasing uniform size, enhanced negative zeta potential, and remarkable stability. Various analyses, from Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-Ray diffraction analysis (XRD), and Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), provide insights into structural integrity and surface modifications. Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) analysis underscores superparamagnetic behavior, positioning these nanocapsules as promising candidates for targeted drug delivery. In vitro evaluations demonstrate dose-dependent inhibition of cell viability in MCF-7 and Zr-75–1 breast cancer cells, emphasizing the therapeutic potential of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU. The interplay of surface charge and pH-dependent cellular uptake highlights the robust stability and versatility of these nanocarriers in tumor microenvironment, paving the way for advancements in targeted drug delivery and personalized nanomedicine. This comparative analysis explores the suitability of silk sericin and gluten, unraveling a promising avenue for the development of advanced, targeted, and efficient breast cancer treatments.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Nanomedicine, Magnetic nanoparticles, Chemodynamic therapy, Protein-based nanocarriers, Silk sericin, Gluten, pH-responsive, Drug delivery, Targeted therapy

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Cancer, Chemical biology, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Health care, Medical research, Oncology

Introduction

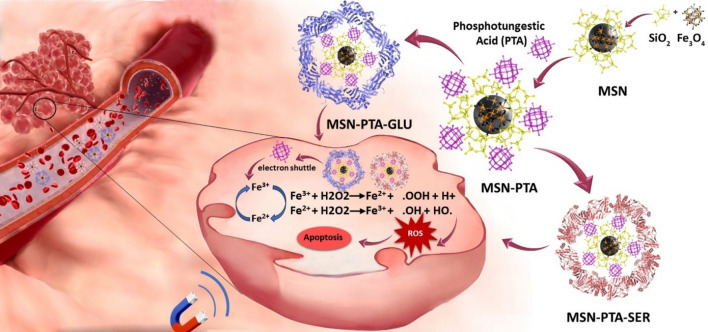

In recent years, the reported number of new breast cancer cases reached approximately 2.3 million worldwide, contributing to an estimated 685,000 deaths attributed to this disease1. So, despite persistent advancements in medical research and technology, breast cancer remains a significant global health concern, ranking as the second most prevalent and fatal malignancy in women’s cancer2,3. Contemporary therapeutic approaches for breast cancer, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, demonstrate efficacy in diminishing the impact of the disease4. The primary mechanism involves cellular disruption, affecting both malignant and normal cells, resulting in undesirable consequences. Challenges associated with this phenomenon include unintended repercussions, negative outcomes, a lack of specificity, heightened toxicity, and the potential for drug resistance5. Nanomedicine offers a hopeful avenue for tackling medical obstacles through the utilization of biocompatible nanoparticles. Specifically, smart drug delivery systems (SDDSs) aim to enhance drug efficacy, minimize toxicity, and improve drug availability through precise administration at targeted sites6, utilizing both internal factors like redox potential, pH levels and external influences such as light, magnetic fields, and ultrasound7–11. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), derived from metals like iron, cobalt, nickel, or metal-polymer blends, are versatile and find applications in various medical fields12, including hyperthermia cancer treatment13, controlled drug release14, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)15, and biosensing16. Specially, magnetic iron oxides, for example magnetite, hematite, and maghemite, offer numerous advantages, including affordability, abundance, low toxicity, stability, biocompatibility, and eco-friendliness17–20. Magnetite, a standout among superparamagnetic nanoparticles, exhibits unique structural and magnetic properties, making it a significant choice for various applications. Cellular responses differ between magnetite and maghemite due to their distinct redox-reactive properties, with magnetite inducing higher levels of oxidative deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) lesions21,22. Magnetite and maghemite, central to superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs), are coated with biocompatible polymers to improve targeting and allow for functionalization, enhancing multifunctionality, where silica coating stands out for its exceptional biocompatibility. However, a notable drawback of chemically synthesized iron nanoparticles is their tendency to aggregate, reducing the surface area-to-volume ratio and potentially causing excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, leading to cell apoptosis or death23–25. Silica-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles prevent aggregation, allowing for selective coupling and labeling of biotargets, enhancing versatility in biomedical applications26,27. Phosphotungstate (PW12O403−, PTA) is a common polyoxometalate featuring the typical Keggin structure28. It is notable for its dual capacity as a chelating agent and a facilitator of electron transfer29. It plays a role in accelerating the electron transfer process from ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+) ions within the nanoparticles30. This property is crucial for the efficient functioning of the Fenton reaction, where the transfer of electrons is essential for the generation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH) from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). (MSN-PTA) enhances the efficiency of chemodynamic therapy (CDT) by participating in the electron transfer process by PTA, facilitating sustained Fenton reaction activity that generates hydroxyl radicals, renowned for their efficacy in damaging cancer cells31. An emerging strategy focuses on protein-based charge-reversal nanocarriers that exhibit responsiveness to pH fluctuations, especially within the acidic tumor microenvironment32. Coating nanoparticles (MSN-PTA) with protein not only aids in targeting cancer cells but also enhance the activation of these particles. Due to the protonation of the functional groups of the protein, the surface charge of the nanocarrier becomes positive, leading to a transition in charge polarity from negative to positive, which aids in their cellular uptake and interaction with negatively charged cell membranes33. Research into protein nanocarriers as drug delivery systems, recognized for their Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status due to exceptional attributes, is currently underway34. These attributes encompass biodegradability, non-antigenicity, abundance from renewable sources, robust drug-binding capacity, and the potential to mitigate Reticuloendothelial System (RES) uptake by forming a spatial hindrance, alongside lacking immune activation effects35. Silk sericin (SS) and gluten, are two proteins under consideration for encapsulating (MSN-PTA) nanoparticles. SS, a pH-responsive protein derived from the silk cocoon of Bombyx mori36, offers sustainability and cost-effectiveness due to its industrial waste utilization37. Silk sericin, a hydrophilic protein with molecular weights ranging from 20 to 400 kDa, encompasses diverse amino acids38, including charged, aromatic, polar, and nonpolar types39,40. Comprised of 18 amino acids, silk sericin features domains with lower molecular weights, enhancing its structural and functional versatility. Sericin's solubility and high hydrophilic amino acid content make it capable of forming stable nanoparticles that encapsulate various compounds. It exhibits multiple beneficial properties like antioxidant, antibacterial, and antitumor activities while allowing prolonged circulation and targeted release of encapsulated compounds41. On the other hand, gluten, primarily composed of gliadin and glutenin proteins, presents a heterogeneous mixture characterized by high glutamine and proline content42. Gliadin's unique composition and properties, including hydrophobicity due to disulfide bonds and cooperative hydrophobic interactions, enable its potential as a biodegradable material for therapeutic applications. Its bioadhesive characteristics on the mucous membrane and solubility in aqueous ethanol binary solvents make gliadin nanocarriers advantageous for encapsulating and targeting hydrophobic compounds in controlled-release delivery systems43. This comparison explores the potential suitability of silk sericin and gluten in encapsulating (MSN-PTA) nanoparticles for breast cancer therapy. A comprehensive schematic diagram illustrating the structures of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU, along with their functional mechanisms in targeted drug delivery, is provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

General schematic of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU and their functional mechanism in targeted drug delivery.

Materials and methods

Materials

Chemicals used in this study include FeCl2·4H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, acid hydrochloride (HCL), ammonium solution (NH4OH), Tetraethyl-ortho-silicate (TEOS), Phosphotungstic acid (PTA), NaOH were purchased from (Merck, Germany), and ethanol (99%) purchased from Dr. Mojalali Co, Iran. Sericin Bombyx mori (silkworm) powder (S5201, reagent grade, ≥ 99%), Gluten from wheat protein (G5004), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), N,N-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), nonsolvent acetone (ACS reagent, ≥ 99.5%) and Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were prepared from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Furthermore, biological materials including Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM), RPMI 1640, and FBS were provided by Gibco BRL Life Technologies. Ultrapure water (UP-Water) was produced using Milli-Q (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Sequence retrieval

In this study, two proteins, namely sericin and gluten, have been employed. Comprising gliadin proteins alongside high molecular weight and low molecular weight glutenin constituents44. The protein sequences for sericin (P07856), Gliadin (P18573), Glutenin, high molecular weight (P10388), and Glutenin, low molecular weight (P10386) were obtained from the UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/). These proteins were chosen due to their amino acid counts closely matched those of the target proteins in this study, enabling insightful comparisons.

Structure prediction by I-TASSER

For proteins not available on the Uniprot website, such as Sericin, we employed I-TASSER (Iterative Threading Assembly Refinement) to predict their structure. The protein sequence was entered into I-TASSER, an internet-based tool that employs a layered methodology to forecast protein structure and function. This tool can be accessed at (https://seq2fun.dcmb.med.umich.edu//I-TASSER/).

Molecular docking analyses with AutoDock4

In our study, we utilized molecular docking analyses to explore the interactions between sericin and gluten with PTA, with the goal of identifying the key amino acids involved in these interactions. AutoDock4 was employed for this investigation, which included the selected sericin protein with PTA, as well as gluten with PTA. The preparation of the macromolecules began with the pre-processing of the RBD protein using AutoDockTools1.5.7. Our methodology encompassed several steps for preparing the molecules. Firstly, we eliminated water molecules and introduced Kollman charges while also adding polar hydrogens, ultimately generating a PDBQT format file. Regarding ligand preparation, we initially sketched the 2D structures of PTA using ChemBioDrawUltra14.0, then transformed them into 3D structures via Chembio3D Ultra14.0. Following this, we performed energy minimization and saved the structure in PDB format. To optimize computational effectiveness, we divided the protein into three grid boxes, strategically positioned and sized. The grid box number 1 for sericin had center coordinates at x = 70.993, y = 91.179, z = 101.504, with dimensions measuring 80 × 75 × 60 Å and a spacing of 0.8 Å. The grid box number 2, centered at x = 113.987, y = 110.149, z = 115.112, had dimensions of 60 × 50 × 90 Å and a spacing of 1 Å. Positioned at x = 152.955, y = 130.116, z = 133.516 nm, the third grid box boasted dimensions of 120 × 80 × 50 Å and a spacing of 0.851 Å. This segmentation approach facilitated the efficient processing of the complex structure, guaranteeing comprehensive coverage and accuracy in this analysis through the use of strategically designed overlapping grid boxes. Additionally, the docking analysis for gluten involved three subtype proteins: gliadin, high molecular weight glutenin, and low molecular weight glutenin, each analyzed separately. For gliadin, the grid box was situated at x = 18.425, y = 31.527, z = 37.938, with dimensions measuring 76 × 60 × 94 Å and a spacing of 0.813 Å. The high molecular weight glutenin grid box was positioned at x = − 6.692, y = 7.518, z = − 5.708, with dimensions of 126 × 126 × 126 Å and a spacing of 1 Å. Lastly, the grid box for low molecular weight glutenin was placed at x = − 4.544, y = 0.334, z = 7.14 nm, boasting dimensions of 108 × 80 × 98 Å and a spacing of 1 Å. To conduct the docking simulation, we employed the AutoDock Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) with 250 runs and 25 million energy evaluations per run to identify optimal combination models. The selection of the most stable clusters was based on the lowest bonding energy, with further confirmation obtained from the amino acid histogram and repetition45.

Preparation and characterization of protein-based nanocarrier

Preparation of MSN

The Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles were synthesized utilizing the nano-precipitation method. Initially, 0.37 g of FeCl2·4H2O and 1.08 g of FeCl3·6H2O were dissolved in 6 mL of HCl (1 mol/L). Upon the addition of 50 mL (5% v/v) of ammonium solution, a yellowish-green solution was formed. The resultant black mixture was then magnetically stirred for a duration of 1 h. The obtained Fe3O4 nanoparticles were subsequently subjected to washing procedures involving deionized water and ethanol. Following this, 0.2 g of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles was dispersed in 40 mL of ethanol and subjected to sonication for 1 h. Subsequently, a solution comprising 4.5 mL of aqueous ammonia, 0.1 mL of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), and 3.7 mL of deionized water underwent sonication for 1 h and stirring for 8 h. The resultant MNPs were separated utilizing a magnetic field and subjected to washing processes. Finally, the synthesized core–shell structured MNPs were dried in an oven at 60 °C.

Synthesis of MSN-PTA

Synthesis of MSN-PTA involved the gradual addition of a solution comprising 0.7 g of PTA dissolved in 5 mL of methanol to a mixture containing 1 g of core–shell magnetic nanoparticles MSN and 50 mL of methanol. Subsequently, the resulting solution underwent sonication for a duration of 1 h. The solution was then subjected to drying using a rotary apparatus at 70 °C.

Protein encapsulation of MSN-PTA

The preparation of protein-based nano capsules commenced with an investigation into the optimal concentration of sericin and gluten proteins through a prior study flash-nanoprecipitation system adapted from our previous work45,46. This study examined various concentrations of Sericin protein, and the concentration of 0.1% (w/v) emerged as the most advantageous, demonstrating favorable physicochemical properties. In this investigation, the loading of MSN-PTA into protein-based nanocapsules was executed by directly adding drop-wise of silk sericin solution (20 µl/5 s) and 2 mg/mL of MSN-PTA into the non-solvent phase (acetone) under high-speed stirring (1200 rpm) at room temperature and pH 7.4. This method was repeated for gluten solution (20 µl/5 s). Notably, this procedure was conducted using only an insulin syringe, delivering one drop per 5 s, without the utilization of any specific tools or devices, while maintaining intense stirring. The resulting protein-based nanocapsules containing the MSN-PTA were obtained through the complete evaporation of water and acetone. Subsequently, the study accomplished the intracellular delivery of MSN-PTA using pH-responsive proteins for potential anticancer therapeutics. Besides evaluating the physical characteristics and stability, the MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU underwent testing to assess variations in quality attributes upon addition to cell culture media.

Basic physicochemical properties

The physicochemical characteristics of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU were examined in this study. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) analysis was employed utilizing the Zetasizer (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) at a controlled temperature of 25 °C. The analysis aimed to ascertain the polydispersity index (PDI), particle size, and particle Zeta Potential of both MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU.

Morphological and structural characteristics

Comprehensive assessments of critical attributes such as aggregation tendencies, morphology, as well as size and shape characteristics of both MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU were conducted using the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (EM3200, KYKY technology Co., China) operating at 25 kV and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Philips EM 208S).

Entrapment efficiency (EE%) and drug loading (DL%) capacities

To evaluate entrapment efficiency and MSN-PTA loading, an ultracentrifugation method was employed. The solutions of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 18,000 rpm for 10 min using the Optimal L-90 k centrifuge (Beckman Coulter Co., USA) to separate the free MSN-PTA from the loaded carriers. Following centrifugation, 1 mL of the supernatant was collected and analyzed with a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Mini 1240, Shimadzu Co., Japan) at 200 nm to determine the concentration of unentrapped MSN-PTA. A standard calibration curve was prepared with MSN-PTA concentrations ranging from 7.8 to 500 µg/mL, resulting in a linear relationship with an r2 of 0.99. Using this calibration curve, the amount of free MSN-PTA was calculated. Finally, the EE% and DL% of MSN-PTA in MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU were calculated using specific formulas (Eqs. 1, 2):

| 1 |

| 2 |

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

To analyze the chemical composition, molecular attributes, and surface adsorption characteristics of nanoparticle functional groups, samples were prepared. These samples included 2 mg each of pure Fe3O4 powder, MSN, and MSN-PTA, as well as 2 mL of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU. Subsequently, the samples underwent a process of homogenization, freeze-drying, and were then ground together with 100 mg of high-quality spectroscopy-grade potassium bromide. The resulting mixture was subsequently positioned in the sample holder of the FT-IR spectrophotometer (IR Prestige-21, Shimadzu Co., Japan) and compressed, facilitating the recording of spectra across a scanning range spanning from 400 to 4000 cm−1, with a spectral resolution set at 4 cm−1.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

TGA was conducted on Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU samples. The process involved accurately weighing 2–8 mg of the dry and unaltered samples, which were then placed into a platinum sample holder while sustaining a controlled nitrogen atmosphere. The measurements were taken over a temperature range spanning from 100 to 900 °C, employing a consistent heating rate set at 10 °C per minute.

X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRD)

XRD analysis was conducted using a Shimadzu XD-610 instrument to elucidate the phase structure of magnetite nanoparticles. X-rays were emitted at a wavelength (λ = 0.15406 nm). This examination, was performed to determine the crystalline structure of the samples including pure Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU.

Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM)

VSM was employed to explore the magnetic characteristics, specifically the magnetization and magnetic field hysteretic cycles, of nanoparticle magnetic samples including Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU. This analysis aimed to ascertain the magnetic saturation values, representing the maximum magnetization achievable under an external magnetic field.

In vitro release profile

The in vitro release behavior of MSN-PTA from MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU was investigated at different pH levels (pH 7, 6) using a dialysis approach. 5 mL aliquot of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU was enclosed in separated dialysis bags with a 20 kDa molecular weight cutoff (Sigma Aldrich) and immersed in 80 mL of release medium (ultrapure water, pH adjusted to 7 or 6 with 1 N HCl). These setups were placed in an orbital shaker (Benchmark Scientific) and maintained at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 50 h. Samples of 1 mL were taken from the release medium at specific time points (0.5, 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 h), replaced with fresh medium, and analyzed by UV–vis spectrophotometry (Mini 1240, Shimadzu Co., Japan) at 200 nm to measure the concentration of MSN-PTA. The release percentages of MSN-PTA from both MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU at each pH level were calculated based on the initial amount of MSN-PTA entrapped.

In vitro biological evaluation of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU

Cell culture model

The study utilized the MCF-7 and Zr-75–1 cell lines derived from human breast adenocarcinoma as an in vitro model. The MCF-7 and Zr-75–1 cell lines, classified as luminal A subtype, exhibit features akin to differentiated mammary epithelium. These include actively expressing estrogen receptors, being responsive to estradiol, and demonstrating the capability for invasion and metastasis, rendering them suitable candidates for our investigation. MCF-7 and Zr-75–1 cells, were nurtured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cell cultures were incubated at 37 °C in an environment with 5% CO2 to ensure optimal growth conditions. The culture medium underwent daily replenishment during the course of the experiment.

Cell viability and cytotoxicity assessment

Cell viability and cytotoxicity assessment were conducted on MCF-7 and Zr-75–1 cells by examining the growth-inhibiting effects of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU at varying concentrations (0.4, 0.6, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 25, and 50 μM) at pH 7.4.

Utilizing a colorimetric MTT assay, we conducted this evaluation according to a well-established procedure. Initially, cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a density of 3 × 103 cells/well. Subsequently, they underwent treatment with MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU at designated concentrations in media with pH 7.4 for durations of 24 and 48 h. Subsequent to the treatment, 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline) was dispensed into each well. The plates were then placed in a 37 °C incubator for 4 h. Following this incubation, the media was aspirated, and a solubilization solution (composed of 10% SDS in 0.01 M HCl) was introduced into each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance readings were obtained at 570 nm using a spectrophotometric plate reader.

Intracellular uptake and DAPI staining

We investigated the cellular uptake of the developed nanoparticles through intracellular uptake procedures. Initially, a suspension of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU (1 mg/mL each) was mixed with FITC (5 μg/mL) and incubated for 12 h in darkness at room temperature. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min, the resulting mixture underwent three washes with PBS. Subsequently, MCF-7 and Zr-75–1 cells were separately plated in 6-well culture dishes at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. Following medium removal and rinsing with PBS, the cells were exposed to stained MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU (1000 μg/mL each) at pH 6 for 8 h. Following this, PBS was used to wash the cells three times, after which they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (100 μL/well) for a duration of 15 min. Subsequently, staining with DAPI (40 μM) was performed to label the cell nuclei. After a 24-h incubation, the cells underwent further PBS washing, fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and two more PBS rinses. DAPI staining was performed for 20 min in the dark to visualize the nuclei. The cells were then washed thrice with PBS, and the wells were examined using a cytation cell imaging reader to analyze the investigation outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the collected data was conducted using SPSS version 23.0 for Windows and GraphPad Prism 8 software. To identify significant differences among the groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. Each experiment was replicated independently three times, and the findings were expressed as mean values ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical significance was established at a p-value less than 0.05.

Results and discussion

Molecular docking analyses

The primary goal of molecular docking is to comparatively analyze sericin and gluten, proteins rich in negatively charged amino acids, as a nanocarrier. Our research focuses on revealing the active domains and specific amino acids within these proteins interacting with phosphotungstic acid, aiming to discern and compare the nature of these interactions and exploring potential implications for biomedical applications. Specifically, sericin exhibits a noteworthy composition with 14% negative aspartic acid content47. Conversely, gluten is characterized by a more substantial presence of negative amino acids, particularly glutamic acid, which constitutes 30–35% of its overall composition48. This investigation is conducted with a specific focus on assessing the interaction of these proteins, specifically their aspartic and glutamic acid residues, with phosphotungstic, thereby elucidating their respective roles in facilitating the coating layer, as a nanocarrier, and augmenting biocompatibility. Also, we focus on the effect of these interactions on zeta potential. Through 250 runs, we analyzed distinct conformational clusters with an RMSD tolerance of 0.5 Å across three grid boxes. The docking computations consistently displayed remarkable performance, with consistently average RMSD values ≤ 1.045. Notably, poses with the highest affinity exhibited lower RMSD values. The analysis highlighted specific amino acids crucial in the PTA-Sericin interaction, including (Asp 209, 202), (Ser 208, 211, 127, 1141, 561, 562, 768), (Arg 292, 399, 515), (Gln 302, 402), (Thr 521), (Asn 295), signifying their significance in the binding process (Fig. 2a). Understanding the dispersion of binding energy within detected clusters were gleaned from the clustering histogram. Cluster 1 in grid box A (Fig. 3a), displaying the lowest binding energy of -4.57 kcal/mol and involving Ser 208 and Asp 209, demonstrated stability. In grid box B (Fig. 3b), a remarkable stability was evident with the lowest binding energy recorded at − 3.53 kcal/mol. This stability was associated with Arg 292, 399, Gln 302, 402, and Asn 295, emphasizing the robustness within this particular region. Meanwhile, in grid box C (Fig. 3c), displayed the minimal binding energy of − 4.59 kcal/mol, involving Ser 561, 562, 768, Arg 515, Thr 521, portraying stability within this region. The concurrent alignment or overlap of these three grid boxes pertaining to sericin was implemented to enhance the precision and accuracy of the docking process.

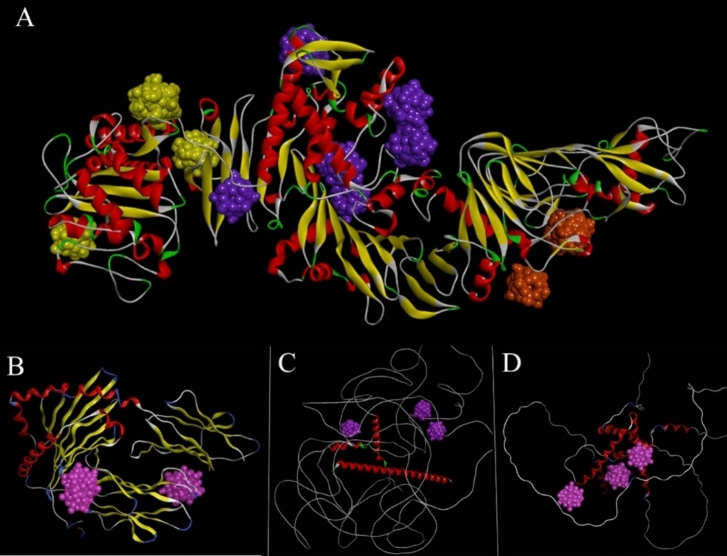

Figure 2.

Possible binding sites of sericin and gluten. (A) showcases the docking of sericin with PTA, highlighting possible binding sites indicated by boxes 1, 2, and 3, depicted in yellow, purple, and orange, respectively. (B–D) Similarly, purple represents the binding sites for the three subtypes of gluten.

Figure 3.

Most important amino acids involved in interactions with PTA. The clusters with the highest stability in terms of energy and reproducibility, along with the critical amino acids engaged in interactions, have been illustrated. Sericin interactions (A–C) correspond to sericin gridboxes 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Similarly, gluten interactions (D–F) are linked to gliadin, glutenin high molecular weight, and glutenin low molecular weight, respectively.

Regarding the PTA-Gluten interaction (Fig. 2b–d), key amino acids crucial for different subtypes were identified. For the Gliadin subtype (Fig. 3d), the lowest binding energy of − 6.44 kcal/mol was associated with stability involving Glu 134, Ser 19, Tyr 16, Gly 20, Gln 14, Pro 115, Lys 147, Val 117. In the Gluten in high molecular weight subtype (Fig. 3e), the lowest binding energy of − 3.87 kcal/mol displayed stability, implicating Thr 499, Gln 569, Ala 568, Leu 567. Similarly, for the Gluten in low molecular weight subtype (Fig. 3f), the most minimal binding energy of − 3.51 kcal/mol was observed, showing stability involving Gln 146, 188, Ser 142, Trp 73. The histogram's distribution pattern highlighted the varied energetically favorable conformations, emphasizing the importance of these findings in understanding the complex molecular landscape of the studied system. As observed, the most stable clusters, characterized by energy values of − 4.57 and − 6.44 kcal/mol, were those composed of the amino acids, aspartic acid and glutamic acid. Specifically in cluster with the most minimal binding energy of − 4.57 kcal/mol, oxygen atoms at positions 25 and 27 in sericin form hydrogen bonds with serine 208 and aspartic acid 209 of the receptor, respectively. With distances of 3.00 Å and 3.16 Å and binding energies of − 0.7 kcal/mol and − 1.4 kcal/mol, these interactions indicate favorable molecular recognition and binding affinities, highlighting the potential importance of hydrogen bonding in the sericin-PTA complex. The docking analysis of gluten with phosphotungstic acid reveals multiple interactions highlighting the molecular recognition between the ligand and the receptor. Notably, the oxygen atom (O) at position 28 in gluten forms a hydrogen bond with GLU 134 at a distance of 3.07 Å, resulting in a significant binding energy of − 4.0 kcal/mol. Additionally, interactions involving LYS 147, GLY 20, GLN 14, TYR 16, and SER 19 exhibit binding energies of − 5.5 kcal/mol, − 2.1 kcal/mol, − 1.9 kcal/mol, − 2.6 kcal/mol, and − 0.8 kcal/mol, respectively. These findings underscore the diverse hydrogen bonding interactions between gluten and phosphotungstic acid, suggesting a complex network of molecular associations that contribute to the stability and specificity of the ligand-receptor complex. Notably, while the gliadin clusters associated with gluten exhibited the lowest bond energy (− 6.44 kcal/mol), it is essential to underscore that the number of binding sites for PTA within sericin (# denoting the frequency of observed binding events in dlg file of docking) surpassed those observed for the gluten clusters. Moreover, the grid boxes designated as Sericin number 1 and 2 exhibited a greater number of binding sites, whereas grid box 3 demonstrated heightened stability in terms of energy, indicative of a more stable binding environment. The extensive analysis underscores the efficacy of blind-docking calculations in predicting favorable binding conformations, revealing distinctive conformational clusters and pivotal amino acids crucial for interactions within PTA-Sericin and PTA-Gluten complexes. Lower RMSD values associated with high-affinity poses affirm the computational reliability in capturing near-native conformations, elucidating the molecular dynamics governing these interactions and highlighting essential binding sites and amino acids. Moreover, clustering histograms depict diverse energetically favorable conformations, emphasizing the intricate nature of protein–ligand interactions and advocating for exploring varied binding modes in protein–ligand design. Special consideration was given to the influence of negatively charged amino acids, particularly aspartic acid and glutamic acid, as these interactions are crucial in regulating the zeta potential of the nanocarrier45. Significantly, our findings highlight Asp 209, 202, and Glu 134 as key contributors, underscoring their substantial roles in orchestrating these interactions through the formation of hydrogen bonds. These insights offer a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the binding dynamics between sericin, gluten, and phosphotungstic acid, with implications for nanocarrier properties.

Development and characterization of protein-based nanocapsules

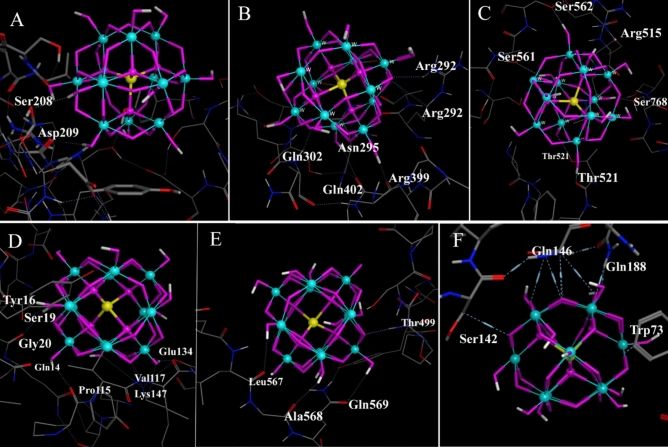

The physicochemical characteristics of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU were investigated in each section. Figure 4, displays DLS measurements for Fe3O4, MSN, and MSN-PTA, revealing average sizes of 37 nm, 71 nm, and 103 nm, respectively, with a Polydispersity Index (PDI) below 0.3. The MSN magnetic nanoparticles exhibited a size of approximately 71 nm, displaying superparamagnetic behavior. The nanoprecipitation method was employed for synthesizing these nanoparticles. To identify the ideal protein concentration for formulating protein nanocapsules, we experimentally tested various concentrations of sericin and gluten. After conducting these inquiries, we opted for the formulation employing proteins at a concentration of 0.1% (w/v) for our experiments45. It's important to highlight that the protein concentration within these nanocarriers can impact their size, with elevated protein concentrations resulting in a broader spectrum of nanoparticle sizes49,50. Protein coating typically imparts favorable attributes such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, reduced immunogenicity, and lower cytotoxicity to MNPs. Sericin markedly increases drug solubility by a factor of 8–tenfold, contrasting with the water insolubility of monomeric gluten, particularly gliadin51,52. The coating of sericin and gluten on MSN-PTA resulted in a marginal increase in size distribution, with an average size of 251 nm and PDI 0.3 for MSN-PTA-SER, and an average size of 314 nm and PDI 0.34 for MSN-PTA-GLU. These findings indicate that the coating procedure resulted in a marginally increased particle size for the gluten-based particles when contrasted with the sericin-based particles. Notably, sericin-based nanocarriers exhibited a more uniform and smaller size than their gluten-based counterparts. Sericin has been systematically investigated for diverse pharmaceutical applications, encompassing solubility augmentation, release profile adjustments, formulation stabilization, and its utilization as a carrier for therapeutic agents53. Remarkably, sericin demonstrates notable solubility, especially at a low concentration of 0.1%, making it an exceptionally promising choice for anti-solvent utilization54. This feature corresponds to the intrinsic traits of proteins with high water solubility, which have garnered significant interest for their effectiveness in methodologies based on anti-solvent precipitation55. The increased size of the coating seen in gluten compared to sericin may be attributed to wheat gluten's restricted solubility in water. This trait is often linked to the significant molecular size and aggregation between molecules of gluten, which arise from strong non-covalent bonds, such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions56. However, it is well known that particles with dimensions below a certain threshold can evade the body's natural clearance mechanisms (RES), resulting in an extended period of circulation for MSN-PTA-SER. Consequently, for optimal cellular uptake and evasion of the RES, the nanocarrier size must fall within this specified range57. Our discovery aligns with a prior investigation in which the smallest concentration of sericin (0.1%) resulted in sericin nanocarriers displaying uniformity in size as measured by DLS, indicating appropriateness45,46.

Figure 4.

DLS analysis of (A) Fe3O4, (B) MSN, (C) MSN-PTA, (D) MSN-PTA-SER, and (E) MSN-PTA-GLU. Zeta potential analysis of (F) Fe3O4, (G) MSN, (H) MSN-PTA, (I) MSN-PTA-SER, (J) MSN-PTA-GLU and (K) Overall comparison of zeta potential of mentioned nanoparticles with zeta of sericin and gluten alone.

In addition, the zeta potential of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA was observed at − 9.97, − 14, and − 18.8 respectively at pH 7.4 (Fig. 4). The isoelectric point (PI) of uncoated MNPs has been documented in the literature to be at pH 6.8, specifically for magnetite58. Therefore, at pH 7.4, as expected, the zeta potential for magnetite − 9.97 was obtained. So Fe3O4 do not benefit from the good stability in aqueous solution. Fe3O4 particles coated with a SiO2 shell exhibit a lower PI of approximately pH 3.959. Consequently, MSN particles possess a higher negative charge compared to bare Fe3O4 nanoparticles, with a measured value of − 14. This lower isoelectric point and increased negative charge contribute to the enhanced stability and dispersibility of MSN magnetic nanoparticles. This suggests that improving these properties for Fe3O4 nanoparticles can be easily achieved by applying a SiO2 coating. Additionally, the zeta potential becomes negative as the pH increases to 7.4 due to the rise in OH− ions in the dissociated solution and subsequent deprotonation60. The Keggin anion tends to agglomerate and create less negative surface charge in comparison to MSN. In solutions with a pH below 8, the inclusion of ethanol or acetone stabilizes the [PW12O40]3− anion, thereby mitigating decomposition61. In our investigation, we examined the zeta potentials of sericin and gluten both independently and as coatings on the magnetic core of nanoparticles. At pH 7.4, sericin alone exhibited a zeta potential of − 15.2 mV, while gluten alone displayed a zeta potential of − 14.3 mV. However, the coating of sericin on the MSN-PTA induced a substantial reduction in zeta potential to − 28.5 mV (MSN-PTA-SER), surpassing the reduction observed for gluten-coated nanoparticles, which reached − 23.3 mV (MSN-PTA-GLU) at pH 7.4. This outcome suggests that the sericin coating imparts a more negative charge to the nanoparticles compared to gluten. Molecular docking results align with this observation, indicating more binding sites for sericin, potentially contributing to the stronger negative zeta potential. Despite the low binding sites in gluten, the most stable cluster in terms of energy was associated with the phosphotungstic interaction with the gliadin subunit of gluten. These findings collectively point towards a greater interaction of sericin with the MSN-PTA, emphasizing the significance of the sericin coating in altering the surface properties and potential applications of the nanoparticles. Particles with zeta potential values around ± 30 mV62, notably observed in MSN-PTA-SER nanoparticles, indicate stability, particularly when compared to gluten-coated nanoparticles. Further exploration of the biological and functional implications of these interactions is warranted for a comprehensive understanding of the observed phenomena.

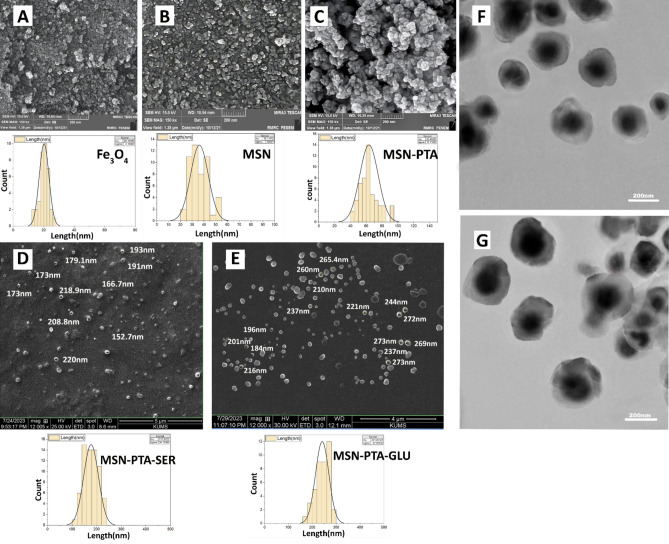

Morphological and structural characteristics

The examination through SEM demonstrated a uniform dispersion of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU, displaying a spherical morphology (Fig. 5). The average diameter observed was consistent with the measurements obtained through DLS for Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU, with values of 20.1 nm, 36.1 nm, 63.4 nm, 177 nm, and 241 nm, respectively. The SEM-determined dry particle size was smaller than that obtained by the DLS, which measures in solution and considers the size increase caused by particle hydration63. SEM analysis performed on three powder samples (Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA) revealed no aggregation in the final syntheses, indicating well-dispersed nanoparticles in the final products. The TEM images provided a detailed visualization of the MSN-PTA-GLU and MSN-PTA-SER morphologies, revealing significant size differences between the samples while both retained a consistent spherical shape. Notably, the MSN-PTA-GLU nanoparticles appeared larger than the MSN-PTA-SER nanoparticles, indicating that the inclusion of gluten influences the overall size more significantly than sericin. The core structures of the magnetic nanoparticles were distinctly visible in the TEM images, highlighting the successful incorporation of the MSN-PTA core within the nanoparticle matrix. This core visibility confirms the magnetic nature of the nanoparticles and provides insight into the core–shell architecture of the synthesized materials. Additionally, the nanoparticles exhibited a predominantly spherical shape across all samples. This spherical morphology is crucial for uniformity in application and enhances the consistency of the nanoparticles' physical and chemical properties.

Figure 5.

SEM and TEM analyses with size distribution assessment performed using Image J. SEM images include: (A) Fe3O4, (B) MSN, (C) MSN-PTA, (D) MSN-PTA-SER, and (E) MSN-PTA-GLU, with detailed size distribution analysis using Image J. TEM images include: (F) MSN-PTA-SER, and (G) MSN-PTA-GLU.

Encapsulation efficiency and drug loading capacities

The EE% of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU were determined to be 94% and 95%, respectively. The higher EE for gluten can be attributed to its larger protein structure, which comprises three subunits. However, under identical conditions, the DL% for both sericin and gluten was found to be 19%. This suggests that despite the high encapsulation efficiencies, the loading capacities for both biopolymers remain at 19%. This discrepancy highlights the distinct behavior of these biopolymers in terms of MSN-PTA release and loading capacities, emphasizing their potential roles and applications in drug delivery systems.

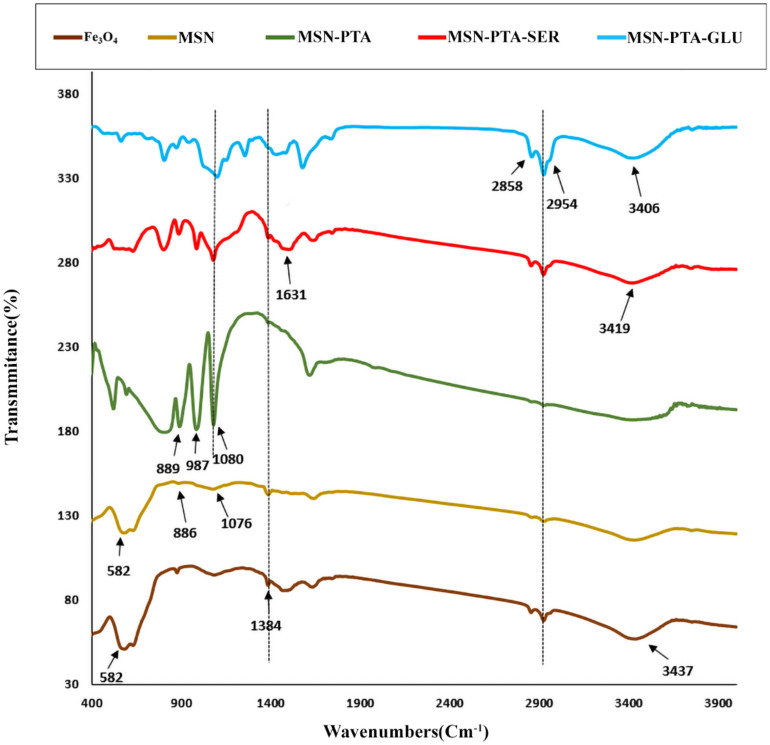

FTIR analysis

The synthesis process of the composite was further explored by examining any alterations in the FTIR spectra of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU (Fig. 6). In the spectrum of Fe3O4, the prominent peak at 582 cm−1 is ascribed to the stretching vibrations of the Fe–O groups within the Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Additionally, the peak observed at approximately 3437 cm−1 is attributed to both the bending and stretching vibrations of –OH groups, originating from both water molecules and surface –OH groups on the particles. In the case of MSN, the F–O adsorption peak is notably evident at 582 cm−1. The most significant alterations, distinguishing it from bare Fe3O4 nanoparticles, include the emergence of a peak at 1076 cm−1 associated with the asymmetrical vibrations of the Si–O–Si group. This peak confirms the successful surface modification with silica. Additionally, the presence of a peak at 886 cm−1 is indicative of the Si–OH bond. The distinctive FTIR bands associated with the Keggin structure are prominently exhibited in pure PTA, featuring peaks at 1080, 987, 889, and 780 cm−1. The observed peaks are associated with distinct vibrational modes: P–Oa, W = Ot, W–Ob–W, and W–OC–W, respectively. These spectral features represent different oxygen configurations within the Keggin framework, including oxygen in the central tetrahedral PO4 (Oa), terminal oxygen linked exclusively to the tungsten atom (Ot), bridge oxygen situated between two separate W3O13 units (Ob), and bridge oxygen within the same W3O13 cluster (OC)64. The FTIR analysis uncovered distinctive peaks in sericin's molecular makeup. At 3419 cm−1, the stretching oscillations of O–H bonds suggested the existence of hydroxyl functional groups. A singular absorption related to amide vibrations at 1631 cm−1, identified as the amide I band, verified the existence of proteins, signifying the stretching oscillations of C = O bonds. Additionally, peaks ranging from 1540 to 1520 cm−1 were linked to the amide II band, originating from N–H bending vibrations. The amide III region, spanning from 1240 to 1384 cm−1, highlighted the presence of a random coil structure within sericin, involving C–N stretching and N–H bending. In contrast, gluten, the wheat-derived protein complex, exhibited peaks corresponding to various functional groups. Notably, the stretching oscillations of gluten N–H bonds at 3406 cm−1 and O–H bonds hinted at the protein's hydroxyl groups. The band at 2954–2958 cm−1 aligns with the stretching vibrations of the CH2– group. Additionally, distinctive peaks corresponding to the amide I and amide II bands were detected at 1635 cm−1 and 1575 cm−1, respectively, with an amide III band ranging from 1200 to 1340 cm−1. These bands are consistent with the characteristic features of gliadins.

Figure 6.

The FT-IR spectra of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU.

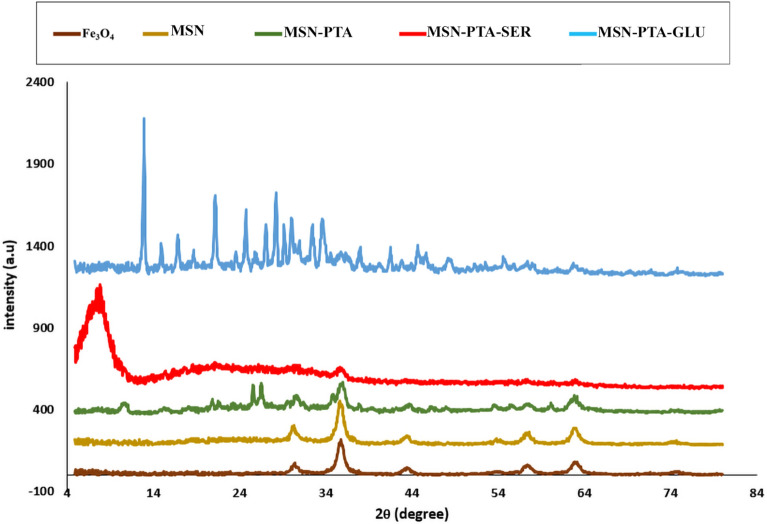

XRD analysis

XRD ascertains the crystalline structure of samples. XRD pattern of pure Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU nanoparticles illustrated in Fig. 7. Peaks at 30.5°, 35.5°, 43.2°, 53.5°, 57.62°, and 62.5° (2θ) were assigned to (220), (311), (400), (422), (511) and (440) miller indices of Fe3O4, respectively. The XRD spectrum of Fe3O4 indicates that the nanoparticles exhibit an inverse spinel structure, characteristic of magnetite. This structure features a cubic lattice with space group Fd3m65,66. The corresponding ICDD file number for magnetite is 19–629, which matches the observed Bragg peaks67. The results suggest that the synthesis of MSN nanoparticles occurred effectively, preserving the crystal structure of the Fe3O4 core. Furthermore, the presence of broad peaks centered around 23° in the MSN sample indicates the formation of an amorphous silica shell encasing the nanoparticles' surface. The XRD pattern shows that there are no other impurity phases present. The XRD pattern of the MNP reveals a diffuse scattering or broad hump around 20° (2θ), as depicted in the Fig. 7. This characteristic feature may be ascribed to the presence of amorphous SiO2 materials. In the case of MSN-PTA, the primary XRD peaks are observed at 2θ values of 10.5, 18.3, 23.7, 26.1, 30.2, 35.6, and 38.8. The observed peaks are consistent with the cubic structure characteristic of Keggin-type heteropolyacids, corroborating findings from previous studies (JCPDS#7521–25)68. XRD analysis of silk sericin indicates a broad diffraction peak appearing at 2θ = 18.86°–20°, attributed to the presence of the amorphous organic phase. Additionally, the highest diffraction peak observed at 2θ = 14.2° suggests a transition from the random coil structure to the β-sheet structure within sericin. This transition is likely facilitated by intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl groups of the amino acids present in sericin69. In contrast, gluten exhibited dual diffraction peaks around 2θ = 10° and 2θ = 20°, signaling its amorphous composition and the presence of α-helix structures. The lower 2θ value peak denotes the typical inter-helix spacing, while the higher 2θ value peak indicates the average distance between helix backbones70.

Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction patterns of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU.

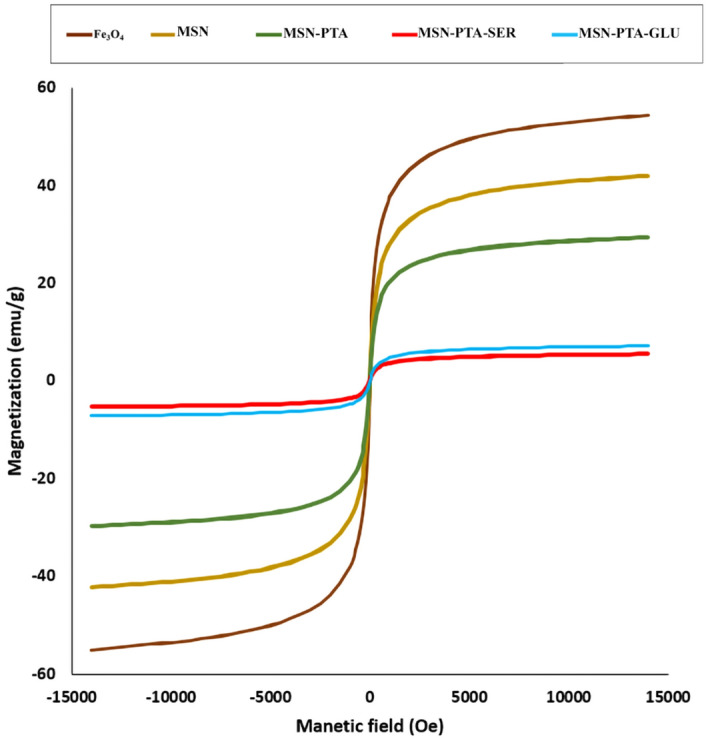

VSM analysis

The primary hysteresis curve analysis of Fe3O4 and its derivatives, namely MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU, was conducted using a VSM (Fig. 8). The magnetization of MNPs were recorded in an applied magnetic field of − 15,000 ≤ H(Oe) ≤ 15,000 at room temperature. The magnetic properties of MNPs and bare MNPs could be seen by magnetic (Ms) attraction. the magnetization curves revealed that the magnetic nanoparticles were superparamagnetic. The magnetization values obtained were 54 emu/g for uncoated Fe3O4, 41 emu/g for MSN, 28 emu/g for MSN-PTA, 6 emu/g for MSN-PTA-GLU, and 5 emu/g for MSN-PTA-SER, as depicted in Fig. 8. The results demonstrate that the coercivity of SiO2-coated and protein-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles is notably lower than that of the uncoated counterparts. The magnetic behavior of magnetite nanoparticles is known to be influenced by dipole–dipole interactions, which are strongly dependent on the interparticle distance. The SiO2 layer enveloping the Fe3O4 nanoparticles in this study serves as an insulating layer, hindering electron transfer, increasing the distance between nanoparticles, and preventing their agglomeration. Consequently, MSN nanoparticles exhibit reduced coercivity71.

Figure 8.

The VSM examination of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU.

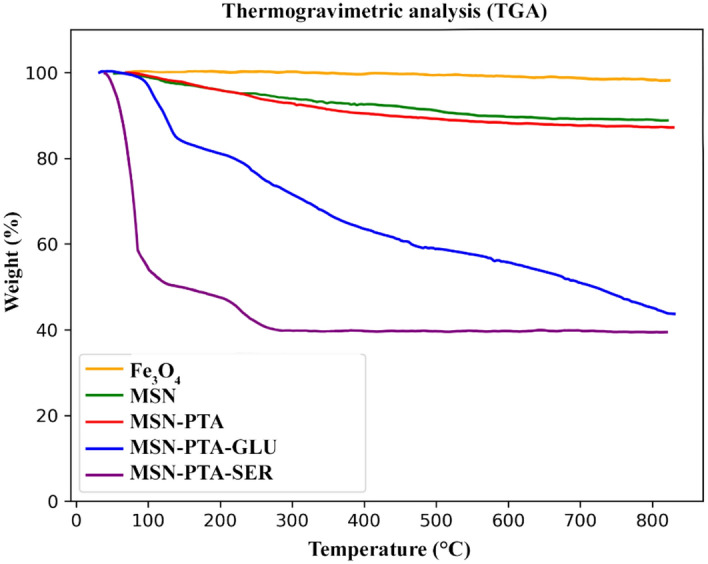

TGA analysis

To determine the weight percentage of Fe3O4 in MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU, TGA was conducted in an air environment from room temperature to 900 °C. In the pure Fe3O4 graph, only a minimal weight loss of 0.8% was observed, attributed to the removal of adsorbed physical and chemical water. The residual mass percentages were used to estimate the magnetite content in the samples. The TGA results depicted in the (Fig. 9) indicate an increase in weight loss above 200 °C, attributed to the removal of the SiO2 layer coated on the Fe3O4. The estimated weight loss of the SiO2 coating on the Fe3O4 nanoparticles is approximately 9.4%. In the graph related to MSN, no significant difference was observed with the graph of MSN-PTA, however, a decrease of 2.4% was observed in the temperature range of 250 and above, which is related to the weight loss of PTA. The TGA results reveal distinct thermal behaviors for magnetic nanoparticles coated with gluten and sericin. The gluten-coated nanoparticles show a gradual weight loss from 100 to 43% across the temperature range of 0 to 900 °C, indicating continuous decomposition of the gluten coating; in Fig. 9, for MSN-PTA-GLU, the initial weight loss stage (below 140 °C) is attributed to the evaporation of water molecules, while the subsequent stage (about 200 °C) corresponds to the decomposition of gluten. On the other hand, sericin-coated nanoparticles exhibit a more intense weight loss from 100 to 39%, followed by a constant weight percentage up to 900 °C. This indicates a rapid and substantial change or decomposition in the sericin coating at the initial stage, with the material remaining stable thereafter. The differences in weight loss patterns provide insights into the distinct thermal stabilities and decomposition characteristics of the gluten and sericin coatings on the magnetic nanoparticles.

Figure 9.

The TGA examination of Fe3O4, MSN, MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU.

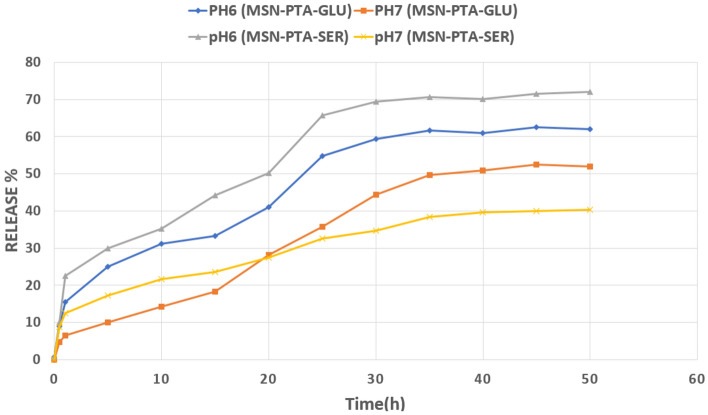

In vitro release profile

The MSN-PTA release test was conducted under laboratory conditions for nanoparticles coated with sericin and gluten over a 50-h period at pH 6 and 7 (Fig. 10). At the 25-h mark, the release percentages for MSN-PTA-GLU were 35% at pH 7 and 54% at pH 6. For MSN-PTA-SER, the release percentages were 32% at pH 7 and 65% at pH 6 after 24 h. By the end of the 50-h period, the release of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU reached their maximum levels: 40% and 71% at pH 7 and 6, respectively, for MSN-PTA-SER, and 51% and 61% at pH 7 and 6, respectively, for MSN-PTA-GLU. The graphs indicate that MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU reach a steady state of approximately 70% and 60%, respectively, after 30 h at pH 6. In contrast, at pH 7, they achieve a steady state of around 40% and 50%, respectively, after 35 h. This difference in release profiles can be attributed to the proteins releasing more quickly and efficiently at the lower pH level. These results indicate that both types of nanoparticles exhibit controlled release capabilities. However, nanoparticles coated with sericin demonstrate a higher release capacity compared to those coated with gluten, attributed to the charge reversal property of sericin at lower pH levels. This means that sericin has more charge reversal properties.

Figure 10.

The in vitro release of MSN-PTA at pH value of 7, 6.

In vitro biological evaluation

Cell viability

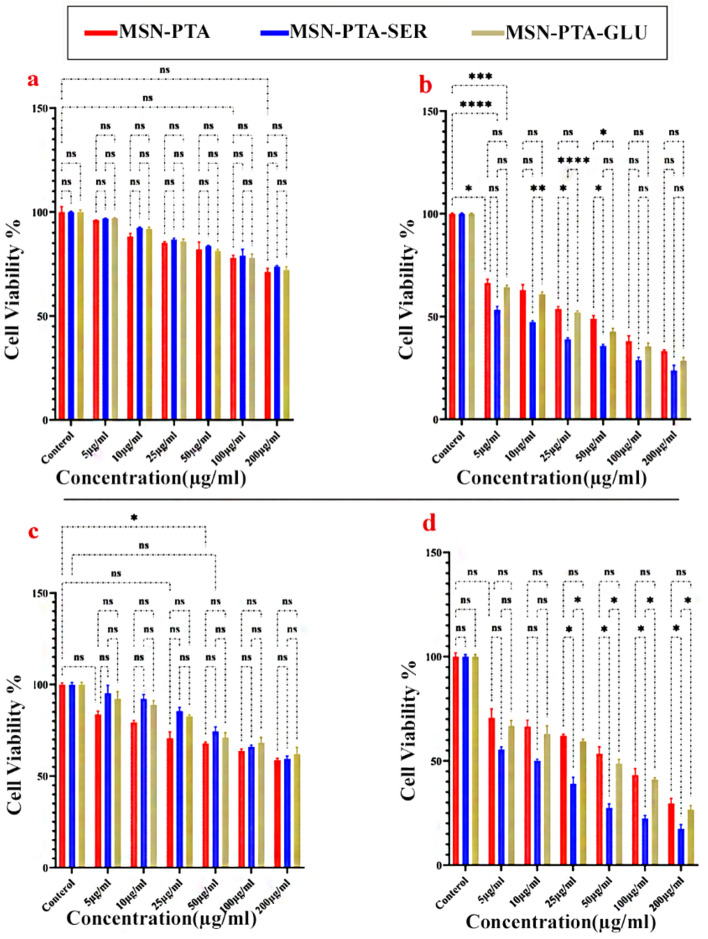

Assessing the capability of MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU (at concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200 μg/mL) on the viability of MCF-7 cells and ZR-75–1 at pH 7.4, the MTT assay was conducted (Fig. 11). After 24 h for MCF-7 (Fig. 11a), a mild reduction in cell viability was noted in the groups treated with MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU compared to the control group. Nevertheless, within 24-h timeframe, this reduction was notably more pronounced for the ZR-75–1 cell group (Fig. 11c). Despite a gradual decrease, no statistically significant differences in cell viability were observed over a 24-h period for both MCF-7 cells and ZR-75–1 when comparing cells treated with MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU, both within each concentration and across different concentrations. Cells subjected to a 48-h treatment exhibited a more pronounced and dose-dependent inhibition. In a 48-h treatment of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 11b) at a concentration of 5 μg/mL, MSN-PTA showed a significant 68% decrease in cell viability (P-value ≤ 0.05), MSN-PTA-GLU exhibited a 64% decrease (P-value ≤ 0.001), and MSN-PTA-SER demonstrated a significant 54% reduction (P-value ≤ 0.0001) compared to the control group. For MCF-7 (Fig. 11b), the decrease and distinction persist until the concentration of 50 μg/mL, which represents the IC50 of MSN-PTA with a statistically significant difference (P-value ≤ 0.05) compared to sericin and gluten-coated particles. At 10 μg/mL (sericin coated IC50), a significant difference (P-value ≤ 0.01) is observed compared to gluten-coated particles, resulting in a 63% reduction in cell viability. Similarly, at 25 μg/mL (gluten coated IC50), a highly significant difference (P-value ≤ 0.0001) is noted compared to sericin-coated particles, accompanied by a 40% reduction in cell viability. Ultimately, for MCF-7 at a concentration of 200 μg/mL nanoparticles coated with sericin, the resulting 25% cell viability did not significantly differ from that observed with gluten-coated nanoparticles at the same concentration. The viability of the ZR-75–1 cell line treated with MSN-PTA-SER exceeded that of the MCF-7 cell line across all doses over a 48-h period (Fig. 11d). This discrepancy, however, led to a notable difference (P-value ≤ 0.05) in the final concentration of 200 μg/mL between sericin and gluten-coated nanoparticles in the ZR-75–1 cell line. In summary, the treatment with MSN-PTA-SER resulted in reduced cell viability for both ZR-75–1 and MCF-7 cells compared to the treatment with MSN-PTA-GLU. These findings suggest that MSN-PTA-SER is a more effective treatment option than MSN-PTA-GLU, and could potentially lead to better outcomes for patients.

Figure 11.

Viability of MCF-7 cells at 24 h (A) and 48 h (B), and ZR-75–1 cells at 24 h (C) and 48 h (D) following exposure to different concentrations of MSN-PTA, MSN-PTA-SER, and MSN-PTA-GLU. Results represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, with statistical significance denoted by *P ≤ 0.05 compared to the respective controls.

Intracellular uptake and DAPI staining

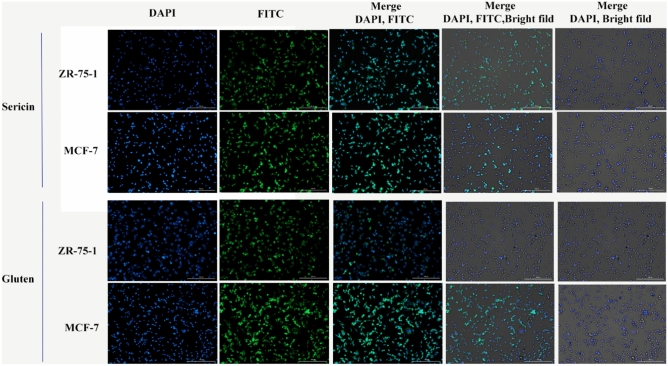

The cytotoxicity of the synthesized MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU nanoparticles was assessed by determining their IC50 values. Subsequently, intracellular uptake and nuclear assessment were evaluated using fluorescence microscopy (Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader). The morphologies of ZR-75–1 and MCF-7 cells were examined after exposure to FITC-labeled nanocarriers for 4 h under acidic conditions (pH 6) (Fig. 12). In our prior investigation, we conducted experiments involving sericin under varying pH conditions to examine drug release dynamics and evaluate cell viability. Results showed that optimal drug release and cellular uptake were observed at pH 6, albeit with a significant reduction in cell viability45,46. Cancer cells typically possess negatively charged surfaces, attributed to the secretion of lactic acid, a metabolic trait resulting from heightened glycolysis rates72. The experimental findings demonstrate the successful cellular uptake of both MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU following a 4-h incubation period, resulting in their localization within the cytoplasm. This uptake was evidenced by the accumulation of the fluorescent dye within the cellular compartments, leading to a notably enhanced green fluorescence intensity compared to the untreated control samples. The increased efficiency of cellular uptake observed for MSN-PTA-SER can be attributed to its transition from a negatively charged surface to a positively charged one under lower pH conditions, along with its comparatively lower zeta potential. Conversely, at pH 7.4, the negative surface charge of both MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU impedes their internalization into the cells due to repulsive electrostatic interactions with negatively charged components such as phospholipid head groups, glycans, and membrane proteins73. Conversely, at a lower pH of approximately 6, aligning with the pI of sericin and gluten, the transformation of surface charge to positive for these nanocarriers enhances its affinity for cell membranes, thereby facilitating the facile internalization of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU by MCF-7 and ZR-75–1 cells (charge reversal effect). To assess the cytotoxic effects of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU, cell nucleus staining was conducted using DAPI. Sericin and gliadin subtype of gluten, have been shown to elevate apoptotic cells and regulate the expression levels of Bax, Bcl‑2, Cyto‑C, and Caspase‑3 in cancer cells, consistent with observations reported in previous studies across diverse cancer cell types74,75. As represented in Fig. 12, significant nuclear changes were detected in MCF-7 and ZR-75–1 cells, as they emit a bright blue fluorescence. It indicated the DNA fragmentation and apoptosis after treatment with IC50 doses of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU. Generally, sericin-based nanocarriers exhibited more robust uptake in both cell lines compared to gluten-based nanocarriers. However, gluten-based nanocarriers demonstrated superior cell uptake specifically in the MCF-7 cell line. This outcome can be ascribed to the more negative zeta potential of sericin nanocarriers, suggesting that the enhanced stability of the nanocarrier led to a further reduction in cell viability, as evidenced by the cell viability test.

Figure 12.

Fluorescence microscopy revealed intracellular uptake of FITC-labeled MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU at pH 6 in MCF-7 cells, alongside DAPI staining for visualizing cell nuclei, presented with a bar scale of 200 nm.

Conclusion

In summary, this study successfully formulates and characterizes protein-coated nanocapsules, specifically sericin-based and gluten-based, exhibiting optimal physicochemical attributes for drug delivery applications. The meticulous optimization of sericin and gluten concentrations results in finely tuned nanoparticles, with sericin and gluten coated nanoparticles showcasing uniform size, enhanced negative zeta potential, and remarkable stability. The comprehensive analyses, spanning from DLS and SEM measurements to FTIR, XRD and TGA examinations, provide a thorough understanding of structural integrity and surface modifications. VSM analysis underscores superparamagnetic behavior, positioning these nanocapsules as promising candidates for targeted drug delivery. In vitro evaluations highlight the dose-dependent inhibition of cell viability, underscoring the therapeutic potential of MSN-PTA-SER and MSN-PTA-GLU. The interplay of surface charge and pH-dependent cellular uptake further accentuates the versatility of these nanocarriers, paving the way for advancements in targeted drug delivery and personalized nanomedicine. Overall, the sericin-based nanocarrier, distinguished by its charge reversal property, emerges as a smaller and more stable alternative, showcasing a significantly more negative zeta potential. Molecular docking results and cellular uptake observations substantiate the efficacy of sericin as a nanocarrier with superior properties for targeted delivery to cancerous cells, especially when contrasted with gluten-based nanoparticles.

Author contributions

S.J. led all laboratory work and compiled primary data; K.B. contributed to writing the manuscript and designing schematic illustration; S.J. and K.B. contributed as co-first authors. E.A. and M.J. contributed to writing specific sections of the article; and F.A. served as the article editor, offering valuable insights and improvements throughout the process.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text and are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. https://research.kums.ac.ir/attachments.json/downloadpdf/279900.pdf.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Saba Jalilian and Kiana Bahremand.

References

- 1.Li, Y. et al. Global burden of female breast cancer: Age-period-cohort analysis of incidence trends from 1990 to 2019 and forecasts for 2035. Front. Oncol.12, 891824 (2022). 10.3389/fonc.2022.891824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giaquinto, A. N. et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin.72, 524–541 (2022). 10.3322/caac.21754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodai, B. I. & Tuso, P. Breast cancer survivorship: A comprehensive review of long-term medical issues and lifestyle recommendations. Perm J.19, 48–79. 10.7812/TPP/14-241 (2015). 10.7812/TPP/14-241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunasekaran, G., Bekki, Y., Lourdusamy, V. & Schwartz, M. Surgical treatments of hepatobiliary cancers. Hepatology73, 128–136 (2021). 10.1002/hep.31325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao, Y. et al. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery in cancer therapy and its role in overcoming drug resistance. Front. Mol. Biosci.7, 193 (2020). 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang, Z., Wan, L.-Y., Chu, L.-Y., Zhang, Y.-Q. & Wu, J.-F. ‘Smart’ nanoparticles as drug delivery systems for applications in tumor therapy. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv.12, 1943–1953. 10.1517/17425247.2015.1071352 (2015). 10.1517/17425247.2015.1071352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong, F., Huang, S. & Gu, N. Magnetic nanoparticles: Recent developments in drug delivery system. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm.44, 697–706 (2018). 10.1080/03639045.2017.1421961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang, H. et al. Visible-light-sensitive titanium dioxide nanoplatform for tumor-responsive Fe2+ liberating and artemisinin delivery. Oncotarget8, 58738 (2017). 10.18632/oncotarget.17639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury, S. M., Lee, T. & Willmann, J. K. Ultrasound-guided drug delivery in cancer. Ultrasonography36, 171 (2017). 10.14366/usg.17021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, H., Fan, T., Chen, W., Li, Y. & Wang, B. Recent advances of two-dimensional materials in smart drug delivery nano-systems. Bioact. Mater.5, 1071–1086 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hossen, S. et al. Smart nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy and toxicity studies: A review. J. Adv. Res.15, 1–18 (2019). 10.1016/j.jare.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alagiri, M., Muthamizhchelvan, C. & Ponnusamy, S. Structural and magnetic properties of iron, cobalt and nickel nanoparticles. Synth. Metals161, 1776–1780 (2011). 10.1016/j.synthmet.2011.05.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kallumadil, M. et al. Corrigendum to “Suitability of commercial colloids for magnetic hyperthermia”[J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 321 (2009) 1509–1513]. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.321, 3650–3651 (2009). 10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.06.069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pankhurst, Q. A., Connolly, J., Jones, S. K. & Dobson, J. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys.36, R167. 10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/201 (2003). 10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, N. & Hyeon, T. Designed synthesis of uniformly sized iron oxide nanoparticles for efficient magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Chem. Soc. Rev.41, 2575–2589. 10.1039/c1cs15248c (2012). 10.1039/c1cs15248c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Issadore, D. et al. Magnetic sensing technology for molecular analyses. Lab Chip14, 2385–2397. 10.1039/C4LC00314D (2014). 10.1039/C4LC00314D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannas, C. et al. Superparamagnetic behaviour of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dispersed in a silica matrix. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.3, 832–838 (2001). 10.1039/b008645m [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotin, G., Piant, S., Mertz, D., Felder-Flesch, D. & Begin-Colin, S. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications 43–88 (Elsevier, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hakkani, M. F., Gouda, G. A. & Hassan, S. H. A review of green methods for phyto-fabrication of hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles and their characterization, properties, and applications. Heliyon7, e05806 (2021). 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma, P. et al. Revisiting the physiochemical properties of Hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticle and exploring its bio-environmental application. Mater. Res. Express6, 095072 (2019). 10.1088/2053-1591/ab30ef [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson, H. L., Cronholm, P., Gustafsson, J. & Moller, L. Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: A comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem. Res. Toxicol.21, 1726–1732 (2008). 10.1021/tx800064j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson, H. L., Gustafsson, J., Cronholm, P. & Möller, L. Size-dependent toxicity of metal oxide particles—A comparison between nano-and micrometer size. Toxicol. Lett.188, 112–118 (2009). 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piao, Y., Burns, A., Kim, J., Wiesner, U. & Hyeon, T. Designed fabrication of silica-based nanostructured particle systems for nanomedicine applications. Adv. Funct. Mater.18, 3745–3758 (2008). 10.1002/adfm.200800731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, W. et al. Insights into the synthesis, types and application of iron nanoparticles: The overlooked significance of environmental effects. Environ. Int.158, 106980. 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106980 (2022). 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ezealigo, U. S., Ezealigo, B. N., Aisida, S. O. & Ezema, F. I. Iron oxide nanoparticles in biological systems: Antibacterial and toxicology perspective. JCIS Open4, 100027. 10.1016/j.jciso.2021.100027 (2021). 10.1016/j.jciso.2021.100027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alterary, S. S. & AlKhamees, A. Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@ SiO2 core@ shell nanostructure. Green Process. Synth.10, 384–391 (2021). 10.1515/gps-2021-0031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abd Elrahman, A. A. & Mansour, F. R. Targeted magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Preparation, functionalization and biomedical application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol.52, 702–712 (2019). 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.05.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keggin, J. The structure and formula of 12-phosphotungstic acid. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Char.144, 75–100 (1934). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, C., Keenan, C. R. & Sedlak, D. L. Polyoxometalate-enhanced oxidation of organic compounds by nanoparticulate zero-valent iron and ferrous ion in the presence of oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol.42, 4921–4926 (2008). 10.1021/es800317j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, J., Kim, J. & Choi, W. Oxidation on zerovalent iron promoted by polyoxometalate as an electron shuttle. Environ. Sci. Technol.41, 3335–3340 (2007). 10.1021/es062430g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao, P. et al. Ferrous-cysteine–phosphotungstate nanoagent with neutral pH fenton reaction activity for enhanced cancer chemodynamic therapy. Mater. Horiz.6, 369–374 (2019). 10.1039/C8MH01176A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, P., Chen, D., Li, L. & Sun, K. Charge reversal nano-systems for tumor therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol.20, 1–27 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu, D. et al. pH-triggered charge-reversal silk sericin-based nanoparticles for enhanced cellular uptake and doxorubicin delivery. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.5, 1638–1647 (2017). 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kariduraganavar, M. Y., Heggannavar, G. B., Amado, S. & Mitchell, G. R. Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery 173–204 (Elsevier, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narwade, M., Gajbhiye, V. & Gajbhiye, K. R. Stimuli-Responsive Nanocarriers 393–412 (Elsevier, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamboni, L., Gauthier, M., Yang, G. & Wang, Q. Silk sericin: A versatile material for tissue engineering and drug delivery. Biotechnol. Adv.33, 1855–1867 (2015). 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo, S.-J., Das, G., Shin, H.-S. & Patra, J. K. Silk sericin protein materials: Characteristics and applications in food-sector industries. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 4951 (2023). 10.3390/ijms24054951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunz, R. I., Brancalhão, R. M., Ribeiro, L. F. & Natali, M. R. Silkworm sericin: Properties and biomedical applications. Biomed Res. Int.2016, 8175701. 10.1155/2016/8175701 (2016). 10.1155/2016/8175701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kundu, S. C., Dash, B. C., Dash, R. & Kaplan, D. L. Natural protective glue protein, sericin bioengineered by silkworms: Potential for biomedical and biotechnological applications. Prog. Polym. Sci.33, 998–1012 (2008). 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu, J.-H., Wang, Z. & Xu, S.-Y. Preparation and characterization of sericin powder extracted from silk industry wastewater. Food Chem.103, 1255–1262 (2007). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhaorigetu, S., Yanaka, N., Sasaki, M., Watanabe, H. & Kato, N. Inhibitory effects of silk protein, sericin on UVB-induced acute damage and tumor promotion by reducing oxidative stress in the skin of hairless mouse. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol.71, 11–17 (2003). 10.1016/S1011-1344(03)00092-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mardliyati, E. & Kaswati, N. M. N. Encapsulation of gluten. Procedia Chem.16, 457–464 (2015). 10.1016/j.proche.2015.12.079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang, S. et al. Impact of different crosslinking agents on functional properties of curcumin-loaded gliadin-chitosan composite nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll.112, 106258 (2021). 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balakireva, A. V. & Zamyatnin, A. A. Properties of gluten intolerance: Gluten structure, evolution pathogenicity and detoxification capabilities. Nutrients10.3390/nu8100644 (2016). 10.3390/nu8100644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bahremand, K., Aghaz, F. & Bahrami, K. Enhancing cisplatin efficacy with low toxicity in solid breast cancer cells using pH-charge-reversal sericin-based nanocarriers: Development, characterization, and in vitro biological assessment. ACS Omega9, 14017–14032 (2024). 10.1021/acsomega.3c09361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aghaz, F. et al. Codelivery of resveratrol melatonin utilizing pH responsive sericin based nanocarriers inhibits the proliferation of breast cancer cell line at the different pH. Sci. Rep.13, 11090 (2023). 10.1038/s41598-023-37668-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Züge, L. et al. Emulsifying properties of sericin obtained from hot water degumming process. J. Food Process Eng.40, e12267 (2017). 10.1111/jfpe.12267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reeds, P. J., Burrin, D. G., Stoll, B. & Jahoor, F. Intestinal glutamate metabolism. J. Nutr.130, 978S-982S. 10.1093/jn/130.4.978S (2000). 10.1093/jn/130.4.978S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbasi Kajani, A., Haghjooy Javanmard, S., Asadnia, M. & Razmjou, A. Recent advances in nanomaterials development for nanomedicine and cancer. ACS Appl. Bio Mater.4, 5908–5925 (2021). 10.1021/acsabm.1c00591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandra, F., Khaliq, N. U., Sunna, A. & Care, A. Developing protein-based nanoparticles as versatile delivery systems for cancer therapy and imaging. Nanomaterials9, 1329 (2019). 10.3390/nano9091329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salunkhe, N. H., Jadhav, N. R., More, H. N. & Jadhav, A. D. Screening of drug-sericin solid dispersions for improved solubility and dissolution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.107, 1683–1691 (2018). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joye, I. J., Nelis, V. A. & McClements, D. J. Gliadin-based nanoparticles: Fabrication and stability of food-grade colloidal delivery systems. Food Hydrocoll.44, 86–93 (2015). 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shitole, M., Dugam, S., Tade, R. & Nangare, S. Pharmaceutical applications of silk sericin. Ann. Pharm. Franç.78, 469–486. 10.1016/j.pharma.2020.06.005 (2020). 10.1016/j.pharma.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tao, G. et al. Bioinspired design of AgNPs embedded silk sericin-based sponges for efficiently combating bacteria and promoting wound healing. Mater. Des.180, 107940 (2019). 10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joye, I. J. & McClements, D. J. Production of nanoparticles by anti-solvent precipitation for use in food systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol.34, 109–123 (2013). 10.1016/j.tifs.2013.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mejri, M., Rogé, B., BenSouissi, A., Michels, F. & Mathlouthi, M. Effects of some additives on wheat gluten solubility: A structural approach. Food Chem.92, 7–15 (2005). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.07.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kommareddy, S. & Amiji, M. Poly (ethylene glycol)-modified thiolated gelatin nanoparticles for glutathione-responsive intracellular DNA delivery. Nanomedicine3, 32–42 (2007). 10.1016/j.nano.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Na, Y., Yang, S. & Lee, S. Evaluation of citrate-coated magnetic nanoparticles as draw solute for forward osmosis. Desalination347, 34–42. 10.1016/j.desal.2014.04.032 (2014). 10.1016/j.desal.2014.04.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cuddy, M. F., Poda, A. R. & Brantley, L. N. Determination of isoelectric points and the role of pH for common quartz crystal microbalance sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces5, 3514–3518. 10.1021/am400909g (2013). 10.1021/am400909g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petrinic, I. et al. Superparamagnetic Fe3O4@ Ca nanoparticles and their potential as draw solution agents in forward osmosis. Nanomaterials11, 2965 (2021). 10.3390/nano11112965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu, Z., Tain, R. & Rhodes, C. A study of the decomposition behaviour of 12-tungstophosphate heteropolyacid in solution. Can. J. Chem.81, 1044–1050 (2003). 10.1139/v03-129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clogston, J. D. & Patri, A. K. Zeta potential measurement. In Characterization of Nanoparticles Intended for Drug Delivery, 63–70 (2011).

- 63.Liu, M. et al. Luminescence tunable fluorescent organic nanoparticles from polyethyleneimine and maltose: Facile preparation and bioimaging applications. RSC Adv.4, 22294–22298 (2014). 10.1039/c4ra03103b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.da Costa, N. L. et al. Phosphotungstic acid on activated carbon: A remarkable catalyst for 5-hydroxymethylfurfural production. Mol. Catal.500, 111334 (2021). 10.1016/j.mcat.2020.111334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arista, D. et al.IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (IOP Publishing, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haavik, C., Stølen, S., Fjellvag, H., Hanfland, M. & Hausermann, D. Equation of state of magnetite and its high-pressure modification: Thermodynamics of the Fe-O system at high pressure. Am. Mineral.85, 514–523 (2000). 10.2138/am-2000-0413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamaura, M. & Fungaro, D. A. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic adsorbent prepared by magnetite nanoparticles and zeolite from coal fly ash. J. Mater. Sci.48, 5093–5101. 10.1007/s10853-013-7297-6 (2013). 10.1007/s10853-013-7297-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Atia, H., Armbruster, U. & Martin, A. Dehydration of glycerol in gas phase using heteropolyacid catalysts as active compounds. J. Catal.258, 71–82 (2008). 10.1016/j.jcat.2008.05.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saha, J., Mondal, M., Sheikh, M. R. & Habib, M. A. Extraction, structural and functional properties of silk sericin biopolymer from Bombyxmori silk cocoon waste. J. Text. Sci. Eng.10.4172/2165-8064.1000390 (2019). 10.4172/2165-8064.1000390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuktaite, R. et al. Changes in the hierarchical protein polymer structure: Urea and temperature effects on wheat gluten films. RSC Adv.2, 11908–11914 (2012). 10.1039/c2ra21812g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thanh, B. T. et al. Immobilization of protein a on monodisperse magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Nanomater.2019, 1–9 (2019). 10.1155/2019/2182471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le, W., Chen, B., Cui, Z., Liu, Z. & Shi, D. Detection of cancer cells based on glycolytic-regulated surface electrical charges. Biophys. Rep.5, 10–18 (2019). 10.1007/s41048-018-0080-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li, Z., Ruan, J. & Zhuang, X. Effective capture of circulating tumor cells from an S180-bearing mouse model using electrically charged magnetic nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol.17, 1–9 (2019). 10.1186/s12951-019-0491-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Niu, L. et al. Sericin inhibits MDA-MB-468 cell proliferation via the PI3K/Akt pathway in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Med. Rep.23, 1–1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perez, F., Ruera, C. N., Miculan, E., Carasi, P. & Chirdo, F. G. Programmed cell death in the small intestine: Implications for the pathogenesis of celiac disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 7426 (2021). 10.3390/ijms22147426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text and are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. https://research.kums.ac.ir/attachments.json/downloadpdf/279900.pdf.