ABSTRACT

Taniborbactam, a bicyclic boronate β-lactamase inhibitor with activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), Verona integron–encoded metallo-β-lactamase (VIM), New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM), extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), OXA-48, and AmpC β-lactamases, is under clinical development in combination with cefepime. Susceptibility of 200 previously characterized carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and 197 multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa to cefepime-taniborbactam and comparators was determined by broth microdilution. For K. pneumoniae (192 KPC; 7 OXA-48-related), MIC90 values of β-lactam components for cefepime-taniborbactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, and meropenem-vaborbactam were 2, 2, and 1 mg/L, respectively. For cefepime-taniborbactam, 100% and 99.5% of isolates of K. pneumoniae were inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively, while 98.0% and 95.5% of isolates were susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam and meropenem-vaborbactam, respectively. For P. aeruginosa, MIC90 values of β-lactam components of cefepime-taniborbactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, ceftolozane-tazobactam, and meropenem-vaborbactam were 16, >8, >8, and >4 mg/L, respectively. Of 89 carbapenem-susceptible isolates, 100% were susceptible to ceftolozane-tazobactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, and cefepime-taniborbactam at ≤8 mg/L. Of 73 carbapenem-intermediate/resistant P. aeruginosa isolates without carbapenemases, 87.7% were susceptible to ceftolozane-tazobactam, 79.5% to ceftazidime-avibactam, and 95.9% and 83.6% to cefepime-taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively. Cefepime-taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively, was active against 73.3% and 46.7% of 15 VIM- and 60.0% and 35.0% of 20 KPC-producing P. aeruginosa isolates. Of all 108 carbapenem-intermediate/resistant P. aeruginosa isolates, cefepime-taniborbactam was active against 86.1% and 69.4% at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively, compared to 59.3% for ceftolozane-tazobactam and 63.0% for ceftazidime-avibactam. Cefepime-taniborbactam had in vitro activity comparable to ceftazidime-avibactam and greater than meropenem-vaborbactam against carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and carbapenem-intermediate/resistant MDR P. aeruginosa.

KEYWORDS: taniborbactam, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, bicyclic boronate, beta-lactamase inhibitor, cefepime taniborbactam

INTRODUCTION

In a recent review by the World Health Organization (WHO) of antimicrobials currently under development, 43 antibiotics and combinations with a new therapeutic entity and 27 non-traditional antibacterial agents were identified (1). Of these, 27 are active against WHO-priority pathogens such as carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, 13 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and five against Clostridioides difficile. Twelve of these agents are β-lactam and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, but it was noted that many are not active against metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) producers. The report also noted that, despite 11 new antibiotics being approved for use since 2017, these agents are from existing classes where resistance mechanisms are well established and have limited clinical benefit over existing treatment. Seven agents fulfilled at least one innovation criterion and two were active against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria. Only two of the seven innovative antibiotics, taniborbactam (formerly VNRX-5133) in combination with cefepime and ledaborbactam (formerly VNRX-7145) in combination with ceftibuten, target at least one of the WHO critical priority antimicrobial-resistant Gram-negative bacterial groups.

β-Lactamase inhibitors have been an important component of antibacterials since the introduction of clavulanate into clinical use in 1984. Three classes of β-lactamase inhibitors are now in clinical use—agents with a β-lactam core (clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam), agents with a diazabicyclooctane (DBO) core (avibactam and relebactam), and agents with a boronic acid core (vaborbactam) (2). Vaborbactam inhibits Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) and other class A carbapenemases (IMI/NMC and SME), but not class D (OXA) or metallo (class B; IMP, NDM, VIM) types (3). Taniborbactam has been reported to have a broader spectrum of direct inhibition than any other β-lactamase inhibitor in use or in advanced clinical development, with cefepime-taniborbactam having similar coverage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales as β-lactam/DBO combinations, including aztreonam-avibactam, and cefiderocol (4, 5). Taniborbactam is under clinical development in combination with cefepime at its highest approved dose (6 g/day in three divided doses) (6, 7). In a phase 3, double-blind, randomized trial, 661 hospitalized adults with complicated urinary tract infections, including acute pyelonephritis, were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive intravenous cefepime-taniborbactam (2.5 g) or meropenem (1 g) every 8 hours for 7 days (or up to 14 days for patients with concurrent bacteriemia) (6). Cefepime-taniborbactam was superior to meropenem regarding the primary composite outcome of both microbiologic and clinical success on trial days 19 to 23, with a treatment difference of 12.6% (95% CI, 3.1%–22.2%; P = 0.009). Higher composite success and clinical success rates were sustained at late follow-up (trial days 28 to 35).

This study was undertaken to evaluate the activity of cefepime-taniborbactam against collections of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa with characterized carbapenem resistance mechanisms, including those found in many regions of the United States (8–11).

RESULTS

K. pneumoniae

Of the 200 isolates tested, 192 contained a class A K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) and seven contained a class D carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase (OXA) variant of OXA-48, with one of these seven also containing a class B New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM). One isolate with CTX-M-15, OXA-1, TEM-1, and SHV-28 β-lactamases had no known carbapenemases. The minimum inhibitory concentration inhibiting 50% or 90% of isolates (MIC50/90) and the percentage susceptible to the agents tested are shown in Table 1. As expected, based on most isolates containing carbapenemases, susceptibility to the β-lactam agents tested—ceftazidime, cefepime, and meropenem—was low (<3%). A majority of isolates were susceptible to amikacin (60.0%), and tigecycline (88.5%), with 77.0% intermediate to colistin.

TABLE 1.

MIC50/90 values and percent susceptibility of K. pneumoniae isolates (n = 200)a

| Agent (susceptible breakpoint, mg/L) | MIC range (mg/L) | MIC50 (mg/L) | MIC90 (mg/L) | Percent susceptible |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin (≤16) | ≤0.5 to >32 | 16 | 32 | 60.0 |

| Colistin (≤2)b | 0.25 to >4 | 0.5 | >4 | 77.0b |

| Ceftazidime (≤4) | 0.5 to >16 | >16 | >16 | 1.0 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam (≤8) | ≤0.06 to >8 | 1 | 2 | 98.0 |

| Cefepime (≤2) | 2 to >16 | >32 | >32 | 1.5 |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam (≤8/≤16)c | ≤0.06 to 16 | 0.25 | 2 | 99.5/100c |

| Meropenem (≤1) | 0.5 to >4 | >4 | >4 | 2.5 |

| Meropenem-vaborbactam (≤4) | ≤0.06 to 16 | ≤0.03 | 1 | 95.5 |

| Tigecycline (≤2) | 0.5 to >4 | 1 | 4 | 88.5 |

MIC values of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are shown as MICs of the β-lactam component.

CLSI interpretation is intermediate with no susceptible category (12).

For comparative purposes only, the percent susceptible for cefepime-taniborbactam corresponds to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤8 and ≤16 mg/L.

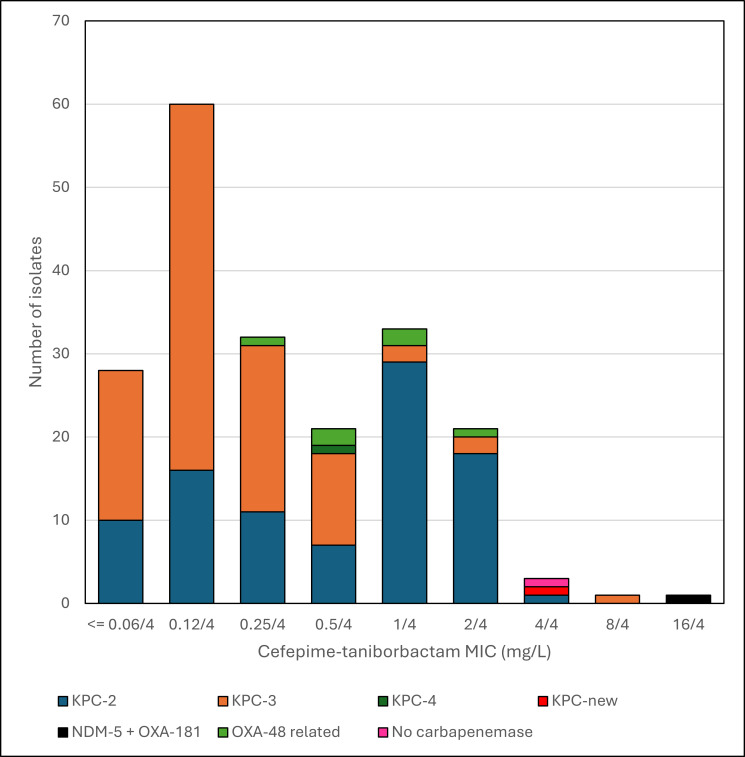

Susceptibility to the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations tested was high: ceftazidime-avibactam (MIC50/90 1/2 mg/L; 98.0% susceptible), cefepime-taniborbactam (MIC50/90 0.25/2 mg/L; 100% and 99.5% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively), and meropenem-vaborbactam (MIC50/90 ≤0.03/1 mg/L; 95.5% susceptible) (Table 1). MIC distributions of cefepime and cefepime-taniborbactam are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. The five isolates with the highest cefepime-taniborbactam MIC values (ranging from 4 to 16 mg/L) were susceptible at a provisional breakpoint of ≤16 mg/L, which is supported by preclinical and clinical data (13–17). MICs for the β-lactam and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations tested against these five isolates, as well as isolates intermediate/resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam and meropenem-vaborbactam and all OXA-producing isolates, are shown in Table 3 with their β-lactam resistance mechanisms. Twelve of these 13 isolates had mutations in ompK35 (n = 12), ompK36 (n = 7), and/or PBP3 genes (n = 1). The ompK35 mutations included insertion sequences (IS), deletions, and premature stop codons. The ompK36 mutations included two di-amino acid insertions. The ftsI mutation encoded a variant PBP3 (F383Y). Six of the seven OXA-48-related producing isolates were intermediate/resistant to meropenem-vaborbactam, with three KPC-producing isolates also resistant to this combination. Four isolates were intermediate/resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam (one OXA-48-related and three KPC-producing). All 13 isolates were inhibited by cefepime-taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L, with 11 (84.6%) inhibited at ≤4 mg/L. The lone isolate in this set with a cefepime-taniborbactam MIC of 16 mg/L harbored both an OXA-48 variant and NDM-5.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of MICs of cefepime alone and in combination with taniborbactam for K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa isolates testeda

| Agent | Number of isolates with MIC value for agent shown (MIC values in mg/L) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | >128 | ||

| K. pneumoniae, all (n = 200) | Cefepime | –b | – | – | – | – | 3 | 3 | 21 | 32 | 141c | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | 28 | 60 | 32 | 21 | 33 | 21 | 3 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | |

| P. aeruginosa, all (n = 197) | Cefepime | – | – | – | – | 9 | 64 | 34 | 25 | 10 | 55c | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | – | – | – | 1 | 38 | 55 | 36 | 34 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | |

| P. aeruginosa, carbapenem resistant, all (n = 108) | Cefepime | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 10 | 21 | 9 | 55c | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | – | – | – | – | 8 | 14 | 22 | 31 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | |

| P. aeruginosa, carbapenem resistant, KPC (n = 20) | Cefepime | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 20c | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| P. aeruginosa, carbapenem resistant, VIM (n = 15) | Cefepime | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 13c | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | – | – | 1 | 3 | |

| P. aeruginosa, carbapenem resistant, other (n = 73) | Cefepime | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 10 | 21 | 7 | 22c | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | – | – | – | – | 8 | 13 | 14 | 26 | 9 | 2 | – | – | 1 | |

| P. aeruginosa, carbapenem susceptible (n = 89) | Cefepime | – | – | – | – | 9 | 51 | 24 | 4 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam | – | – | – | 1 | 30 | 41 | 14 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | |

MIC values of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are shown as MICs of the β-lactam component.

No isolates with MIC indicated or concentration not tested.

MIC value greater than the previous MIC value.

Fig 1.

Histogram of cefepime-taniborbactam MICs of K. pneumoniae by carbapenemase type.

TABLE 3.

β-Lactam resistance mechanisms and MICs of β-lactams and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agents of K. pneumoniae isolates with the highest cefepime-taniborbactam MIC values (≥4 mg/L), intermediate/resistant to one or more of the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agents and/or producing OXA-48-derived β-lactamasesa

| Resistance mechanisms | MIC (mg/L) by agent | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate no. | β-Lactamases | Porin OmpK35 | Porin OmpK36 | PBP3b | Ceftazidime | Ceftazidime- avibactam | Cefepime | Cefepime- taniborbactam | Meropenem | Meropenem- vaborbactam |

| CRK0103 (ALRG2756) | OXA-181, NDM-5, SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15 | Lesionc | TD insertioni | WTk | >16 | >8 | >16 | 16 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0102 (ALRG2757) | OXA-181, SHV-11, CTX-M-15 | Lesionc | TD insertioni | WT | >16 | 0.5 | >16 | 1 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0297 (ALRG2881) | OXA-48, SHV-11, TEM-1 | Lesiond | Intact | WT | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.5 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0298 (ALRG2882) | OXA-48, SHV-11, TEM-1, | Lesiond | Intact | WT | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.25 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0035 (ALRG2946) | OXA-48, OXA-1, SHV-1, CTX-M-15 | Intact | Intact | WT | >16 | 1 | >16 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| CRK0299 (ALRG3126) | OXA-232, SHV-1, TEM-1 | Lesione | TD insertioni | WT | >16 | 1 | >16 | 2 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0300 (ALRG3143) | OXA-232, SHV-1, TEM-1 | Lesione | TD insertioni | WT | >16 | 1 | >16 | 1 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0188 (ALRG1995) | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-1 | Lesionf | GD insertioni | WT | >16 | 4 | >16 | 4 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0089 (ALRG2019) | KPC-3, SHV-12 | Lesionf | Intact | F383Y | >16 | >8 | >16 | 8 | >4 | 0.5 |

| CRK0154 (ALRG2490) | KPC-2, SHV-11 | Lesionf | GD insertioni | WT | >16 | 2 | >16 | 2 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0114 (ALRG2834) | KPC-4, SHV-1, OXA-1, TEM-1 | Lesiong | Intact | WT | >16 | >8 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.03 |

| CRK0113 (ALRG2835) | KPC-new (KPC-4 W105G), SHV-1 | Lesiong | Lesionj | WT | >16 | >8 | >16 | 4 | >4 | >4 |

| CRK0080 (ALRG2512) | CTX-M-15, OXA-1, TEM-1, SHV-28 | Lesionh | Intact | WT | >16 | 1 | >16 | 4 | 1 | 0.12 |

MIC values of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are shown as MICs of the β-lactam component.

PBP3, penicillin-binding protein 3.

IS insertion at codon 274.

Frameshift by 11-bp deletion starting at codon 254.

Premature stop at codon 107.

1-bp insertion at codon 40.

2-bp insertion at codon 20.

1-bp insertion at codon 179.

Key di-amino acid insertion (TD or GD) in the extracellular loop 3 region that restricts entry of many β-lactams into the bacterial cell (18).

IS insertion at codon 82.

Wild-type.

P. aeruginosa

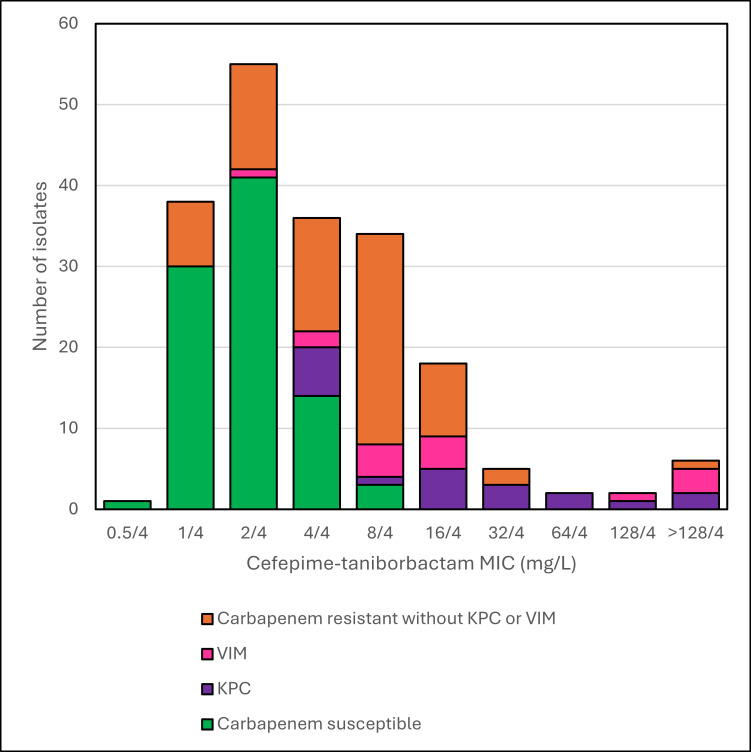

Of the 197 tested MDR isolates of P. aeruginosa, 89 were carbapenem-susceptible and 108 were intermediate/resistant, with carbapenem resistance associated with porin changes or efflux pumps (n = 73), and with the presence of acquired carbapenemases, KPC (n = 20) and VIM (n = 15). MIC distributions of cefepime-taniborbactam by carbapenem resistance mechanism are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. MIC50/90 values and percentage of isolates susceptible to agents tested are shown in Table 4 for all isolates and by carbapenem resistance mechanism. Overall, amikacin (89.3% susceptible) and cefepime-taniborbactam (92.4% and 82.7% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively) were the most active agents, followed by ceftazidime-avibactam (79.7%), tobramycin (78.6%), and ceftolozane-tazobactam (77.7%). Greater than 95% of isolates in the carbapenem-susceptible group (n = 89) were susceptible to the agents tested, except for aztreonam (88.8% susceptible). In the carbapenem-intermediate/resistant group without KPC or VIM (n = 73), amikacin (97.3% susceptible), ceftolozane-tazobactam (87.7%), cefepime-taniborbactam (95.9% and 83.6% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively), and tobramycin (82.2%) were the most active agents, and these four agents were also the most active against all carbapenem-intermediate/resistant isolates (n = 108). In the KPC group (n = 20), only amikacin (55.0% susceptible), ceftazidime-avibactam (50.0%), and cefepime-taniborbactam (60.0% and 35.0% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively) had any activity among the tested agents. In the VIM group (n = 15), only cefepime-taniborbactam (73.3% and 46.7% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively), aztreonam (33.3%), and amikacin (6.7%) had any activity. MICs of the β-lactams and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations tested for isolates with KPC (n = 11) or VIM (n = 7) and susceptible to one or more of the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agents are shown in Table 5. In this isolate set (n = 18), cefepime-taniborbactam (83.3% and 77.8% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L and ≤8 mg/L, respectively) was the most active agent, followed by ceftazidime-avibactam (55.6% susceptible) and aztreonam (16.7% susceptible, n = 3 isolates, all producing VIM). All isolates with VIM were resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam, while 10 of the 11 isolates with KPC were susceptible. Cefepime-taniborbactam was active against 8 of the 11 isolates with KPC and all 7 with VIM.

Fig 2.

Histogram of cefepime-taniborbactam MICs of P. aeruginosa by carbapenem resistance mechanism.

TABLE 4.

MIC50/90 values and percent susceptibility of P. aeruginosa isolates (n = 197)a

| Agent (susceptible breakpoint, mg/L) | All (n = 197) | Carbapenem susceptible (n = 89) | Carbapenem intermediate/ resistant, KPC (n = 20) |

Carbapenem intermediate/ resistant, VIM (n = 15) |

Carbapenem intermediate/ resistant, other (n = 73) |

All carbapenem intermediate/ resistant (n = 108) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50/90 | %S | MIC50/90 | %S | MIC50/90 | %S | MIC50/90 | %S | MIC50/90 | %S | MIC50/90 | %S | |

| Amikacin (≤16) | 4/64 | 89.3 | 4 | 100.0 | 16/>32 | 55.0 | >32/>32 | 6.7 | 4/16 | 97.3 | 4/>32 | 76.9 |

| Aztreonam (≤8) | 8/>16 | 53.8 | 4/16 | 88.8 | >16/>16 | 0.0 | 16/>16 | 33.3 | >16/>16 | 38.4 | >16/>16 | 25.0 |

| Ceftolozane-tazobactam (≤4) | 0.5/>8 | 77.7 | 0.5/1 | 100.0 | >8/>8 | 0.0 | >8/>8 | 0.0 | 1/8 | 87.7 | 4/>8 | 59.3 |

| Ceftazidime (≤8) | 4/>16 | 60.9 | 2/8 | 97.8 | >16/>16 | 0.0 | >16/>16 | 0.0 | 16/>16 | 45.2 | >16/>16 | 30.6 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam (≤8) | 2/>8 | 79.7 | 2/4 | 100.0 | 8/>8 | 50.0 | >8/>8 | 0.0 | 4/>8 | 79.5 | 8/>8 | 63.0 |

| Cefepime (≤8) | 4/>32 | 67.0 | 2/4 | 98.9 | >16/>16 | 0.0 | >16/>16 | 0.0 | 8/>16 | 60.3 | >16/>16 | 40.7 |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam (≤8)b | 4/16 | 82.7 | 2/4 | 100.0 | 16/128 | 35.0 | 4/>128 | 46.7 | 8/16 | 83.6 | 8/32 | 69.4 |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam (≤16)b | 4/16 | 92.4 | 2/4 | 100.0 | 16/128 | 60.0 | 4/>128 | 73.3 | 8/16 | 95.9 | 8/32 | 86.1 |

| Imipenem (≤2) | 4/>4 | 45.2 | 1/2 | 100.0 | >4/>4 | 0.0 | >4/>4 | 0.0 | >4/>4 | 0.0 | >4/>4 | 0.0 |

| Meropenem (≤2) | 1/>4 | 55.8 | 0.25/0.5 | 100.0 | >4/>4 | 0.0 | >4/>4 | 0.0 | >4/>4 | 28.8 | >4/>4 | 19.4 |

| Meropenem-vaborbactamc | 1/>4 | –d | 0.12/0.5 | – | >4/>4 | – | >4/>4 | – | >4/>4 | – | >4/>4 | – |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam (≤16) | 8/>64 | 56.8 | 4 | 97.8 | >64/>64 | 0.0 | >64/>64 | 0.0 | 32/>64 | 34.2 | >64/>64 | 23.1 |

| Tobramycin (≤4) | 0.5/>8 | 78.6 | 0.5/1 | 100.0 | >8/>8 | 0.0 | >8/>8 | 0.0 | 0.5/>8 | 82.2 | 1/>8 | 61.1 |

MIC values of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are shown as MICs of the β-lactam component.

For comparative purposes only, the percent susceptible for cefepime-taniborbactam corresponds to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤8 and ≤16 mg/L.

No CLSI breakpoint is available.

Not applicable.

TABLE 5.

MICs of β-lactam and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations of 18 P. aeruginosa isolates with KPC or VIM and susceptible to one or more of the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agentsa,b

| Agent (susceptible breakpoint, mg/L) | MICs (mg/L) of 11 KPC-producing isolates | MICs (mg/L) of 7 VIM-producing isolates | Percent susceptible | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aztreonam (≤8) | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16.7 |

| Ceftolozane-tazobactam (≤4) | >8 | >8 | 8 | 8 | >8 | >8 | 8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 0 |

| Ceftazidime (≤8) | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | 0 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam (≤8) | 8 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 4 | >8 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 2 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 55.6 |

| Cefepime (≤8) | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | 16 | >16 | >16 | >16 | 16 | >16 | >16 | 0 |

| Cefepime-taniborbactam (≤8/≤16)c | 4 | 32 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 128 | >128 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 77.8/83.3 |

| Meropenem (≤2) | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | 4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | 0 |

| Meropenem-vaborbactamd | 4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | 4 | –e |

MIC values of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are shown as MICs of the β-lactam component; shaded results indicate MICs in the susceptible range.

All other KPC- (n = 9) and VIM-producing isolates (n = 8) were intermediate/resistant to aztreonam and the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agents tested.

For comparative purposes only, the percent susceptible for cefepime-taniborbactam corresponds to the percentage of isolates inhibited at ≤8 and ≤16 mg/L.

No CLSI breakpoint is available.

Not applicable.

DISCUSSION

In a recent review of eight β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors in development, the authors concluded that these agents provide various levels of in vitro coverage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, with only cefepime-zidebactam, aztreonam-avibactam, meropenem-nacubactam, and cefepime-taniborbactam showing in vitro activity against isolates producing MBLs (19). Cefepime-zidebactam and cefepime-taniborbactam were also noted to have in vitro activity against carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, and cefepime-zidebactam and sulbactam-durlobactam against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (19). Among these β-lactamase inhibitors, only taniborbactam has been shown in vitro to inhibit class B metallo-β-lactamases (NDM, VIM, and SPM, but not IMP) (4, 5).

Recent publications have documented the in vitro activity of cefepime-taniborbactam. A study by Mushtaq et al. showed that cefepime-taniborbactam was active against Enterobacterales with KPC, other class A, OXA-48-like, VIM, and NDM carbapenemases, with MICs similar to those of ceftazidime-avibactam for Enterobacterales with KPC or OXA-48-like carbapenemases and a wider spectrum (3). Against the subset Enterobacterales with NDM (n = 124), cefepime-taniborbactam inhibited 89 (71.8%) isolates at ≤8 mg/L and 98 (79.0%) at ≤16 mg/L compared to <1% susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam and meropenem-vaborbactam. The cefepime-taniborbactam MIC90 value for Enterobacterales with KPC in that study (0.5 mg/L) was similar to that in our study (2 mg/L). In a study by Wang et al., taniborbactam was reported to improve the activity of cefepime to the same level that avibactam improved the activity of ceftazidime against 66 KPC-2 producers and 30 non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-intermediate/resistant Enterobacteriaceae (20). Vazquez-Ucha et al. reported cefepime-taniborbactam MIC90 of 2 mg/L against a collection of 400 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales, noting that activity was excellent against OXA-48- and KPC-producing Enterobacterales but lower against MBL-producing isolates (21). Kloezen et al. found that cefepime-taniborbactam demonstrated potent activity against ESBL-producing Enterobacterales, restoring the susceptibility of all isolates tested (22). Karlowsky et al. tested the in vitro activity of cefepime-taniborbactam and comparators against a 2018–2020 collection of 13,731 Enterobacterales and 4,619 P. aeruginosa isolated from patients in 56 countries (23). This study showed that cefepime-taniborbactam exhibited potent in vitro activity against Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa and inhibited most carbapenem-resistant isolates, including isolates carrying serine carbapenemases (KPC) or metallo-β-lactamases (NDM or VIM). Against Enterobacterales, MIC90 was 0.25/4 mg/L, with 99.7% susceptible at a breakpoint of ≤16/4 mg/L. Against P. aeruginosa, MIC90 was 8 mg/L, with 97.4% susceptible at a breakpoint of ≤16/4 mg/L.

Our study provides additional data showing that the activity of cefepime-taniborbactam is comparable to that of ceftazidime-avibactam and meropenem-vaborbactam against carbapenem-resistant, predominantly KPC-producing, K. pneumoniae (100% of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L; MIC50/90 0.25/2 mg/L) (Table 1). Cefepime-taniborbactam was active (MICs 0.5 to 16 mg/L) against all study isolates, including 10 isolates intermediate/resistant to one or more of the other β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agents tested (Table 3). These isolates had several resistance mechanisms, including OXA-48-derived β-lactamases, mutations in the major porin genes ompK35 and ompK36, associated with decreased drug permeability (18), or the ftsI (PBP3) gene, associated with decreased cefepime binding (24) (Table 3). Mutations in the porin gene ompK35 included IS insertion at codon 274 (n = 2), frameshift by 11 bp deletion starting at codon 254 (n = 2), premature stop at codon 107 (n = 2), 1 bp insertion at codon 40 (n = 3), 2 bp insertion at codon 20 (n = 2), and 1 bp insertion at codon 179 (n = 1). Mutations in porin gene ompK36 included TD or GD insertion in the extracellular loop (n = 6) and IS insertion at codon 82 (n = 1). An F383Y mutation in the ftsI (PBP3) gene was present in one isolate.

A limitation of our study is that the isolates contained a limited spectrum of β-lactamases other than KPC. Only seven isolates produced OXA-48-derived β-lactamases, with one of these coproducing a MBL (NDM-5).

Our study also shows that the activity of cefepime-taniborbactam is comparable to that of ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam against carbapenem-resistant MDR P. aeruginosa not associated with carbapenemases (95.9%/83.6% of isolates susceptible at ≤16 mg/L/≤8 mg/L) and has activity against some VIM-producing isolates (73.3%/46.7% of isolates inhibited at ≤16 mg/L/≤8 mg/L) (Table 4). Both ceftazidime-avibactam (50% susceptible) and cefepime-taniborbactam (60%/35% inhibited at ≤16 mg/L/≤8 mg/L) had activity against some KPC-producing P. aeruginosa isolates. According to ongoing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance, non-carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa overwhelmingly represents the most prevalent genotype among carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa in the United States, where 97.8% of 68,172 isolates tested as of June 2023 did not carry a carbapenemase gene (25). In the present study, cefepime-taniborbactam at ≤16 mg/L inhibited 70/73 (95.9%) of carbapenem-intermediate/resistant, non-carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa isolates, a greater proportion than the percentage of these isolates that were susceptible to ceftolozane-tazobactam (87.7%) and ceftazidime-avibactam (79.5%).

In conclusion, cefepime-taniborbactam was active against most isolates in a set of carbapenem intermediate/resistant K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa isolates with carbapenem resistance mechanisms representative of those currently found in these species in the United States. Cefepime-taniborbactam was very active against KPC-producing K. pneumoniae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

K. pneumoniae study isolates included 200 clinical isolates collected from 2012–2016 in the Great Lakes Region as part of the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) Consortium on Resistance against Carbapenems in Klebsiella (CRACKLE-I) Study (26). All isolates had previously been characterized as being carbapenem-resistant, with 199 containing a known carbapenemase determined from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (NCBI BioProject PRJNA339843 and PRJNA433394). One isolate contained CTX-M-15, OXA-1, TEM-1, and SHV-28 β-lactamases.

P. aeruginosa study isolates included 197 MDR clinical P. aeruginosa isolates collected as part of the Platforms for Rapid Identification of MDR-Gram-negative bacteria and Evaluation of Resistance Studies IV (PRIMERS-IV) study (11). These isolates came primarily from northeast Ohio and the mid-Atlantic states. Approximately half had been determined to be carbapenem-resistant when initially characterized. Isolates had been tested using two molecular diagnostic platforms, the Acuitas Resistome test (OpGen Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) and VERIGENE Gram-negative blood culture test (VERIGENE BC-GN, Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX), to identify genes that potentially confer resistance associated with porins, efflux pumps, and the presence of acquired carbapenemases (KPC and VIM).

MICs of cefepime-taniborbactam and comparators were determined using Sensititre custom frozen panels (ThermoFisher, Cleveland, OH) inoculated using cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth (ThermoFisher). Taniborbactam was supplied by Venatorx Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Malvern, PA). In-house frozen panels were used to obtain cefepime-taniborbactam MIC endpoints of up to 128 mg/L for isolates with MICs of >8 mg/L from the initial panel. β-Lactamase inhibitors were tested at fixed concentrations in combination with varying concentrations of β-lactams, with avibactam, tazobactam, taniborbactam, and tazobactam tested at 4 mg/L and vaborbactam at 8 mg/L. Panels were inoculated according to standard methods and were read visually after incubation as previously described (9, 10). MICs were interpreted using CLSI M100-S30 standard (12), with two exceptions. Meropenem-vaborbactam MICs for P. aeruginosa were not interpreted due to a lack of applicable breakpoints in the CLSI M100-S30 standard. Cefepime-taniborbactam MICs against both Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa were interpreted using provisional breakpoints of ≤8 mg/L and ≤16 mg/L (susceptible) and >16 mg/L (resistant) (23), based upon in vivo efficacy data from neutropenic murine infection models (thigh, complicated urinary tract, lung) (13, 14, 17) and data from safety and pharmacokinetics studies in human volunteers (15, 16). Quality control isolates E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 35218, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA-1705, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were tested on each day of testing.

MIC values were analyzed and MIC distributions, categorical susceptibility, and MIC50 and MIC90 values were determined. Categorical susceptibility results were classified into two groups—susceptible and intermediate/resistant, the latter including intermediate, susceptible dose-dependent, and resistant interpretations. MIC values of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are shown as MICs of the β-lactam component.

The genetic basis of β-lactamase, porin ompK35 and ompK36, and ftsI (penicillin-binding protein 3, PBP3) genes in isolates of K. pneumoniae intermediate/resistant to one or more of the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor agents tested or producing OXA-48-derived β-lactamases was determined by analysis of results of previously performed WGS (26) with reference genomes as follows. WGS analysis from the genome assembly and FASTQ files (NCBI BioProject PRJNA339843 for CRK0001-CRK0191 and PRJNA433394 for CRK0192-CRL0390) was performed using Geneious Prime version 2023.2 (Biomatters Inc., Boston, MA, USA). β-Lactamases in each genome were annotated using a search set of 90 representative β-lactamases with a cut-off of 40% identity and BLAST search at the Beta-Lactamase DataBase (BLDB) (http://www.bldb.eu/) (27). This search set identifies all ∼2,000 β-lactamases included in ResFinder 4.1 (28). The genes encoding major porins (ompK36 and ompK35) and the ftsI gene encoding PBP3 (the major target of cefepime) were analyzed using the gene sequences of a reference genome (Nucleotide accession NZ_KN046818.1).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was sponsored by Venatorx Pharmaceuticals Inc. and funded in part with federal funds from the Department of Health and Human Services; Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, under Contract No. HHSO100201900007C. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R21AI114508. Additional funds and/or facilities were provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs to R.A.B. and K.M.P.-W., the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program Awards 1I01BX001974 (R.A.B.) and 1I01BX002872 (K.M.P.-W.) from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development, and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center VISN 10 (R.A.B.). Bacterial isolates identified as “ARLG” were provided by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group Laboratory Center, which is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1AI104681.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, Department of Health and Human Services, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Presented at: Partial results of this work were presented at IDWeek 2021, 29 September to 3 October 2021, as oral presentation 133 and poster presentation 1063.

Contributor Information

Robert A. Bonomo, Email: Robert.Bonomo@va.gov.

Alessandra Carattoli, Universita degli studi di roma La Sapienza, Rome, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . 2022. 2021 antibacterial agents in clinical and preclinical development: an overview and analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240047655 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tooke CL, Hinchliffe P, Bragginton EC, Colenso CK, Hirvonen VHA, Takebayashi Y, Spencer J. 2019. β-lactamases and β-lactamase inhibitors in the 21st century. J Mol Biol 431:3472–3500. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mushtaq S, Vickers A, Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Woodford N, Livermore DM. 2021. Activity of β-lactam/taniborbactam (VNRX-5133) combinations against carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 76:160–170. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamrick JC, Docquier J-D, Uehara T, Myers CL, Six DA, Chatwin CL, John KJ, Vernacchio SF, Cusick SM, Trout REL, Pozzi C, De Luca F, Benvenuti M, Mangani S, Liu B, Jackson RW, Moeck G, Xerri L, Burns CJ, Pevear DC, Daigle DM. 2020. VNRX-5133 (Taniborbactam), a broad-spectrum inhibitor of serine- and metallo-β-lactamases, restores activity of cefepime in Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e01963-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01963-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu B, Trout REL, Chu G-H, McGarry D, Jackson RW, Hamrick JC, Daigle DM, Cusick SM, Pozzi C, De Luca F, Benvenuti M, Mangani S, Docquier J-D, Weiss WJ, Pevear DC, Xerri L, Burns CJ. 2020. Discovery of taniborbactam (VNRX-5133): a broad-spectrum serine- and metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor for carbapenem-resistant bacterial infections. J Med Chem 63:2789–2801. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wagenlehner FM, Gasink LB, McGovern PC, Moeck G, McLeroth P, Dorr M, Dane A, Henkel T, Team C-S. 2024. Cefepime-taniborbactam in complicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med 390:611–622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2304748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Venatorx Pharmaceuticals . 2023. Cefepime-taniborbactam vs meropenem in adults with VABP or ventilated HABP (CERTAIN-2). Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06168734?id=NCT06168734&rank=1

- 8. van Duin D, Arias CA, Komarow L, Chen L, Hanson BM, Weston G, Cober E, Garner OB, Jacob JT, Satlin MJ, et al. 2020. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 20:731–741. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30755-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobs MR, Good CE, Hujer AM, Abdelhamed AM, Rhoads DD, Hujer KM, Rudin SD, Domitrovic TN, Connolly LE, Krause KM, Patel R, Arias CA, Kreiswirth BN, Rojas LJ, D’Souza R, White RC, Brinkac LM, Nguyen K, Singh I, Fouts DE, van Duin D, Bonomo RA, for the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group . 2020. ARGONAUT II study of the in vitro activity of plazomicin against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00012-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jacobs MR, Abdelhamed AM, Good CE, Rhoads DD, Hujer KM, Hujer AM, Domitrovic TN, Rudin SD, Richter SS, van Duin D, Kreiswirth BN, Greco C, Fouts DE, Bonomo RA. 2019. ARGONAUT-I: activity of cefiderocol (S-649266), a siderophore cephalosporin, against Gram-negative bacteria, including carbapenem-resistant nonfermenters and Enterobacteriaceae with defined extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e01801-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01801-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Evans SR, Tran TTT, Hujer AM, Hill CB, Hujer KM, Mediavilla JR, Manca C, Domitrovic TN, Perez F, Farmer M, Pitzer KM, Wilson BM, Kreiswirth BN, Patel R, Jacobs MR, Chen L, Fowler VG, Chambers HF, Bonomo RA, Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) . 2019. Rapid molecular diagnostics to Inform empiric use of ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: PRIMERS IV. Clin Infect Dis 68:1823–1830. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 30th informational supplement. In CLSI document M100-S30. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abdelraouf K, Almarzoky Abuhussain S, Nicolau DP. 2020. In vivo pharmacodynamics of new-generation β-lactamase inhibitor taniborbactam (formerly VNRX-5133) in combination with cefepime against serine-β-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:3601–3610. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abdelraouf K, Stainton SM, Nicolau DP. 2019. In vivo pharmacodynamic profile of ceftibuten-clavulanate combination against extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the murine thigh infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00145-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dowell JA, Dickerson D, Henkel T. 2021. Safety and pharmacokinetics in human volunteers of taniborbactam (VNRX-5133), a novel intravenous β-lactamase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e0105321. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01053-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dowell JA, Marbury TC, Smith WB, Henkel T. 2022. Safety and pharmacokinetics of taniborbactam (VNRX-5133) with cefepime in subjects with various degrees of renal impairment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e0025322. doi: 10.1128/aac.00253-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lasko MJ, Nicolau DP, Asempa TE. 2022. Clinical exposure-response relationship of cefepime/taniborbactam against Gram-negative organisms in the murine complicated urinary tract infection model. J Antimicrob Chemother 77:443–447. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. David S, Wong JLC, Sanchez-Garrido J, Kwong HS, Low WW, Morecchiato F, Giani T, Rossolini GM, Brett SJ, Clements A, Beis K, Aanensen DM, Frankel G. 2022. Widespread emergence of OmpK36 loop 3 insertions among multidrug-resistant clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog 18:e1010334. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yahav D, Giske CG, Grāmatniece A, Abodakpi H, Tam VH, Leibovici L. 2020. New β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Clin Microbiol Rev 34:e00115-20. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00115-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang X, Zhao C, Wang Q, Wang Z, Liang X, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Meng H, Chen H, Li S, Zhou C, Li H, Wang H. 2020. In vitro activity of the novel β-lactamase inhibitor taniborbactam (VNRX-5133), in combination with cefepime or meropenem, against MDR Gram-negative bacterial isolates from China. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:1850–1858. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vazquez-Ucha JC, Lasarte-Monterrubio C, Guijarro-Sanchez P, Oviano M, Alvarez-Fraga L, Alonso-Garcia I, Arca-Suarez J, Bou G, Beceiro A. 2021. Assessment of activity and resistance mechanisms to cefepime in combination with the novel beta-lactamase inhibitors zidebactam, taniborbactam and enmetazobactam against a multicenter collection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01676-21:AAC0167621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kloezen W, Melchers RJ, Georgiou PC, Mouton JW, Meletiadis J. 2021. Activity of cefepime in combination with the novel β-lactamase inhibitor taniborbactam (VNRX-5133) against extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing isolates in in vitro checkerboard assays. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e02338-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02338-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karlowsky JA, Hackel MA, Wise MG, Six DA, Uehara T, Daigle DM, Cusick SM, Pevear DC, Moeck G, Sahm DF. 2023. In vitro activity of cefepime-taniborbactam and comparators against clinical isolates of Gram-negative Bacilli from 2018 to 2020: results from the global evaluation of antimicrobial resistance via surveillance (GEARS) program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 67:e0128122. doi: 10.1128/aac.01281-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hernández-García M, García-Castillo M, Nieto-Torres M, Bou G, Ocampo-Sosa A, Pitart C, Gracia-Ahufinger I, Mulet X, Pascual Á, Tormo N, Oliver A, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Cantón R. 2024. Deciphering mechanisms affecting cefepime-taniborbactam in vitro activity in carbapenemase-producing enterobacterales and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas spp. isolates recovered during a surveillance study in Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 43:279–296. doi: 10.1007/s10096-023-04697-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control . 2024. Antimicrobial resistance & patient safety portal (AR&PSP) AR lab network data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. Available from: https://arpsp.cdc.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Duin D, Perez F, Rudin SD, Cober E, Hanrahan J, Ziegler J, Webber R, Fox J, Mason P, Richter SS, Cline M, Hall GS, Kaye KS, Jacobs MR, Kalayjian RC, Salata RA, Segre JA, Conlan S, Evans S, Fowler VG Jr, Bonomo RA. 2014. Surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: tracking molecular epidemiology and outcomes through a regional network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4035–4041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02636-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naas T, Oueslati S, Bonnin RA, Dabos ML, Zavala A, Dortet L, Retailleau P, Iorga BI. 2017. Beta-lactamase database (BLDB) - structure and function. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 32:917–919. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2017.1344235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bortolaia V, Kaas RS, Ruppe E, Roberts MC, Schwarz S, Cattoir V, Philippon A, Allesoe RL, Rebelo AR, Florensa AF, et al. 2020. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]