ABSTRACT

Escherichia coli ST131 is a multidrug-resistant lineage associated with the global spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing organisms. Particularly, ST131 clade C1 is the most predominant clade in Japan, harboring blaCTX-M-14 at a high frequency. However, the process of resistance gene acquisition and spread remains unclear. Here, we performed whole-genome sequencing of 19 E. coli strains belonging to 12 STs and 12 fimH types collected between 1997 and 2016. Additionally, we analyzed the full-length genome sequences of 96 ST131-H30 clade C0 and C1 strains, including those obtained from this study and those registered in public databases, to understand how ST131 clade C1 acquired and spread blaCTX-M-14. We detected conjugative IncFII plasmids and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 in diverse genetic lineages of E. coli strains from the 1990s to the 2010s, suggesting that these plasmids played an important role in the spread of blaCTX-M-14. Molecular phylogenetic and molecular clock analyses of the 96 ST131-H30 clade C0 and C1 strains identified 8 subclades. Strains harboring blaCTX-M-14 were clustered in subclades 4 and 5, and it was inferred that clade C1 acquired blaCTX-M-14 around 1993. All 34 strains belonging to subclade 5 possessed blaCTX-M-14 with ISEcp1 upstream at the same chromosomal position, indicating their common ancestor acquired blaCTX-M-14 in a single ISEcp1-mediated transposition event during the early formation of the subclade around 1999. Therefore, both the horizontal transfer of plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 to diverse genetic lineages and chromosomal integration in the predominant genetic lineage have contributed to the spread of blaCTX-M-14.

KEYWORDS: extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), Escherichia coli, ST131-H30, chromosomal integration, bla CTX-M-14

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli sequence type (ST)131 is a global multidrug-resistant (MDR) lineage mainly causing bloodstream and urinary tract infections (1–3). Recent studies using whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have revealed the sublineage structure of ST131, classifying it into clades A, B, and C, each defined by the allele of the type 1 fimbriae fimH adhesin: H41 in clade A, H22 in clade B, and H30 in clade C (4, 5). Molecular clock analysis inferred that mutations in gyrA and/or parC, part of the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR), were acquired around 1987 in clade C, leading to its divergence into clades C1 and C2 (6). These clades are strongly associated with CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes (blaCTX-M), each possessing a clade-specific blaCTX-M (7).

Clade C2, also known as H30Rx, commonly harbors blaCTX-M-15 and is predominant in Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia (3). Conversely, clade C1 strains, also known as H30R, typically possess blaCTX-M-9-group genes, including blaCTX-M-14, and are prevalent in Japan, Korea, China, Spain, and Canada (3, 8).

The blaCTX-M genes are originally derived from chromosomal β-lactamase genes of Kluyvera spp. (blaKLU) and are often carried on plasmids specific to each type of blaCTX-M (9). The acquisition process of blaCTX-M by clinically relevant species such as E. coli is proposed to occur as follows (10): an insertion sequence (IS), such as ISEcp1, inserts upstream of blaKLU. The IS transposes blaKLU from the chromosome of Kluyvera spp. to a plasmid via transposase activity. This plasmid is subsequently transferred horizontally to other bacterial species, including E. coli.

Plasmids are generally grouped based on incompatibility (11, 12). IncF family plasmids, which possess a toxin-antitoxin system, tend to be stably maintained in bacterial cells (13). Therefore, the transposition of antimicrobial resistance genes into IncF plasmids is particularly concerning for the dissemination of MDR bacteria, as it may lead to the fixation of resistance genes within the host strain lineage. In ST131-H30 clade C2, some IncF plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-15 have been reported, such as pEC958 with plasmid sequence type (pST) [F2:A1:B-] and pC15-1a with pST [F2:A-:B-], known as the epidemic plasmid in Canada (14–16). In clade C1 strains, an IncF plasmid carrying blaCTX-M-27, with pST [F1:A2:B20], is widespread in Japan (17). Although there are few reports of blaCTX-M-14 being carried on the IncF [F1:A2:B20] plasmid (18), the number of strains carrying it on the chromosome has been increasing recently (19, 20). Chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 is mostly accompanied by ISEcp1, which is located upstream and possesses high transposase activity (21).

In Japan, ST131 strains harboring blaCTX-M-14 have been isolated since 2000, with most of them belonging to clade C1 (22). However, investigations on ST131-H30 clade C1 strains isolated during the early emergence period have been limited, primarily using draft WGS data. Consequently, the genetic structure of the plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 has not been fully characterized in many cases, making it unclear how blaCTX-M-14 was acquired and subsequently stabilized in ST131-H30 clade C1.

This study aimed to characterize the plasmids that contributed to the spread of blaCTX-M-14 and to elucidate the evolutionary process of E. coli ST131-H30 clade C1 with blaCTX-M-14. We performed a retrospective analysis using full-length WGS of E. coli strains isolated during the period when the isolation frequency of E. coli with blaCTX-M-14 increased in Japan. In addition, we compared the full-length genome sequences of ST131-H30 strains analyzed in this study with those in public databases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and genome data

As part of a previous study, we performed a draft WGS of 79 E. coli strains with the blaCTX-M-9-group (23). The strains were selected from an original collection of 329 E. coli strains exhibiting the ESBL phenotype, isolated from humans, companion animals, chicks, and broilers from 1997 to 2019 in Japan. Multiplex PCR for blaCTX-M genes and PCR-based plasmid Inc grouping were performed on these isolates, and 79 strains harboring blaCTX-M-9-group, with no redundant isolation year and plasmid Inc group, were selected for draft WGS (24, 25) (Fig. S1; Table S1). Full-length genome sequencing was also performed for one of these strains (TUM2805).

In the present study, we selected 18 additional strains with different combinations of ST, fimH type, and plasmid Inc group based on draft WGS data for full-length genome sequencing using Illumina and nanopore sequencers to obtain complete genome sequences of plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 (Table S2).

As for the IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids harboring blaCTX-M-14, a comparative analysis of genetic structural similarity was performed (Fig. S2 and S3), followed by a search for similar plasmids in public databases (Fig. 1 and 2).

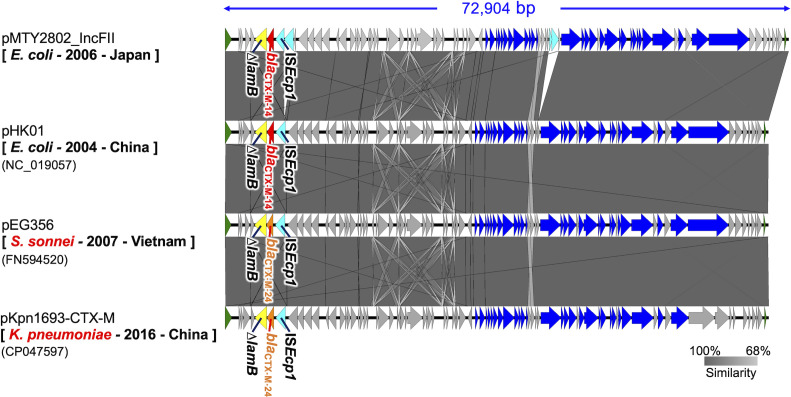

Fig 1.

Structural comparison of IncFII plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 in this study and those in public databases. The gray scale indicates similarity of the genome sequence, with closer to black indicating higher similarity. Block arrows indicate confirmed or putative open reading frames (ORFs) and their orientations. Arrow size is proportional to the predicted ORF length. The meanings of the arrow colors are as follows: red, blaCTX-M-14; orange, blaCTX-M-24; yellow, ∆lamB; cyan, transposase genes; blue, conjugal transfer genes; green, replication initiation protein gene; fuchsia, other antimicrobial resistance genes. Putative, hypothetical, and unknown genes are represented by gray arrows. Square brackets indicate host species, isolation year, and country, and parentheses indicate the accession number of the plasmid.

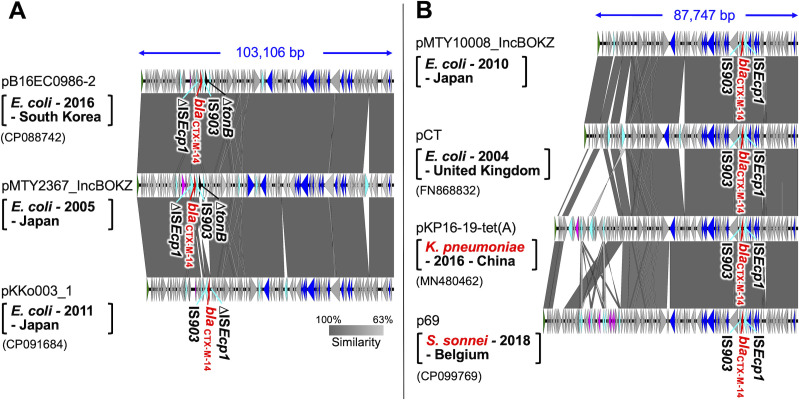

Fig 2.

Structural comparison of IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 in this study and those in public databases. The gray scale indicates similarity of the genome sequence, with closer to black indicating higher similarity. Block arrows indicate confirmed or putative open reading frames (ORFs) and their orientations. Arrow size is proportional to the predicted ORF length. The meanings of the arrow colors are as follows: red, blaCTX-M-14; black, ∆tonB; cyan, transposase genes; blue, conjugal transfer genes; green, replication initiation protein gene. Putative, hypothetical, and unknown genes are represented by gray arrows. The A-type pMTY2367_IncBOKZ is shown in (A), and the B-type pMTY10008_IncBOKZ is shown in (B). Square brackets indicate host species, isolation year, and country, and parentheses indicate the accession number of the plasmid.

In this study, we focused on ST131-H30 strains and obtained genomic data registered in public databases such as GenBank (26). The complete genome sequences of E. coli (n = 3,010, accessed on 29 July 2022) underwent multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and fimH typing to extract the genome sequences of E. coli ST131-H30. Based on the information registered in the BioSample database or relevant literature, we excluded sequences originating from the same strain or lacking information about the isolation year or geographic location. To determine the process by which E. coli ST131-H30 isolated worldwide acquired and stabilized blaCTX-M-14, we performed plasmid analysis and molecular phylogenetic analysis on the four strains newly sequenced in this study and 141 strains from public databases (Fig. S5). The genetic structure similarity of the IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids commonly possessed by ST131-H30 clade C strains was compared (Fig. S6). Among the 145 strains, 96 clade C1 strains were analyzed using molecular phylogenetic and molecular clock analysis to characterize the evolutionary process (Fig. 3).

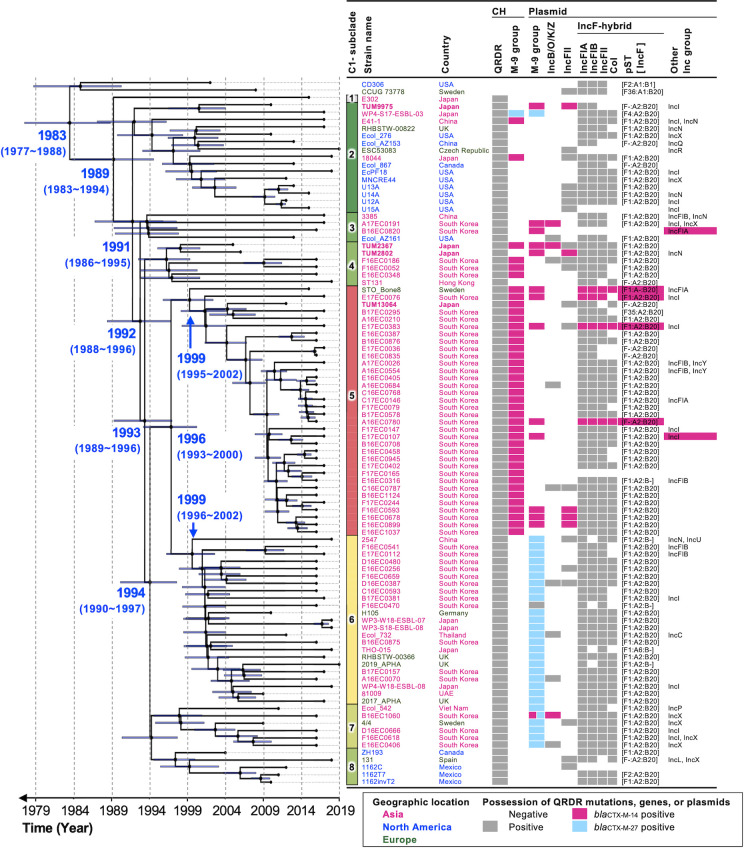

Fig 3.

A time-calibrated phylogeny of E. coli ST131-H30 clade C0 (n = 2) and C1 (n = 94). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using BEAST v.2.6.7 based on 2,401 bp single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the core genome, excluding homologous recombination regions, for 96 strains in this study and in the public database. The core-genome region comprised 83.6% (4,241,105/5,073,822 bp) of the genome of the reference strain, E. coli strain CD306 (GenBank accession number NZ_CP013831). We used the Hasegawa, Kishino, and Yano substitution model and strict clock model. The Markov chain Monte Carlo generations were performed for 30 million steps and sampled every 5,000 steps. The x-axis indicates the time estimates for the emergence of the corresponding subclade. CH indicates the chromosome. Isolated countries were classified by geographic region according to the following colors: fuchsia, Asia; blue, North America; green, Europe.

Draft whole-genome sequencing

DNA was extracted from bacterial cells using a boiling method and subsequently purified using Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). DNA libraries were prepared using the Illumina DNA Prep Kit (Illumina, Inc., CA, USA) and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) with 250 bp paired-end reads or a MiSeq (Illumina) with 300 bp paired-end reads. The sequencing read data were trimmed for adapter sequences and reads not passing a quality score of Q30 or higher using Trimmomatic version 0.39 (27). The trimmed reads were then assembled de novo using SPAdes version 3.15.2 (28).

Species identification was performed by average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis using FastANI version 1.32 (29) against the E. coli type strain DSM 30083 (= JCM 1649 = ATCC 11775) genome (GenBank accession no. CP033092). ANI values above 95% confirmed the strain as E. coli (29, 30).

MLST, fimH typing, identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes, detection of QRDR mutations, plasmid Inc grouping, and plasmid MLST (pMLST) were performed using MLST version 2.0, FimTyper version 1.1, ResFinder version 4.1, PointFinder version 2.1, PlasmidFinder version 2.1, and pMLST version 2.0, respectively. We ran those programs with default parameters. These resources are available at the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (https://www.genomicepidemiology.org/).

Long-read sequencing and hybrid assembly with Illumina reads

High molecular weight DNA was extracted from cultured bacterial cells using the NucleoBond AXG 20 column (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan) combined with the NucleoBond Buffer Set III (TaKaRa Bio). DNA libraries were prepared using the Rapid Barcoding Kit SQK-RBK004 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies: ONT, Oxford, UK) and sequenced using the MinION flow cell R9.4 (ONT) on a MinION Mk1B (ONT). Basecalling and demultiplexing were performed using Guppy v5.0.11 (ONT).

MinION reads were adapter trimmed and quality filtered using NanoFilt version 2.6.0 with a quality score cutoff of Q6 and a minimum length of 5,000 bp (31). The generated reads were subsequently assembled with the Illumina reads, which had been trimmed using Trimmomatic version 0.39 with a quality score cutoff of Q30, using Unicycler version 0.4.8-beta (32). The contigs were polished three times using Pilon version 1.23 (33) based on the Illumina reads. Default parameters were used for all software unless otherwise noted.

Plasmid analysis

Full-length genome sequences were annotated with open reading frames (ORFs) and genes using the DNA Data Bank of Japan Fast Annotation and Submission Tool (34). Insertion sequences and antimicrobial resistance gene locations were confirmed using Prokka version 1.14.6 (35) and ResFinder version 4.1, respectively. Plasmid structure comparisons were performed using EasyFig version 2.2.2 (36). We further targeted the earliest-dated plasmids in each of the detected Inc groups from various genetic lineages and searched public databases for plasmids with similar structures using Nucleotide BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The obtained plasmid sequences were subsequently compared for similarity.

Core-genome SNP-based phylogenetic analysis of E. coli ST131-H30

Core-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based phylogenetic analysis was performed on the complete genome sequences of E. coli ST131-H30 strains. First, we simulated short reads based on the contigs generated by the SimSeq simulator (37). These simulated reads were aligned to the genome sequence of a reference strain using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner with the “SW” option (38). The reference strains used were E. coli EC958 (GenBank accession no. HG941718) for analysis involving the entire clade C, and E. coli CD306 (GenBank accession no. NZ_CP013831) for analysis involving clades C0 and C1.

Core-genome alignments were extracted using SAMtools version 1.17 mpileup (39) and VarScan version 2.3.9 mpileup2cns (40). Temporal phylogenetic trees were estimated based on the maximum likelihood method using PhyML version 20120412 (41). These trees were used as starting trees to infer homologous recombination events that imported DNA fragments from strains outside the phylogenetic clade, and a clonal phylogeny with corrected branch lengths was constructed using ClonalFrameML version 1.12 (42). Phylogenetic trees based on SNPs detected in the core genome, excluding homologous recombination regions inferred by ClonalFrameML, were generated by RAxML version 8.2.12 (43) using 1,000 bootstraps and the gamma site substitution model. All trees were visualized using Figtree version 1.4.4.

To further investigate the divergence within clade C1, we performed molecular clock analysis using BEAST version 2.6.7 (44) on 2,401 SNPs in the core genome of 96 strains belonging to clades C0 and C1. We used the Hasegawa, Kishino, and Yano substitution model and a strict clock model. The Markov chain Monte Carlo generations were performed for 30 million steps, with samples taken every 5,000 steps.

Conjugation experiments

In order to verify whether IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids contribute to the spread of blaCTX-M-14 in E. coli, conjugation experiments were performed using the filter mating method. The donor strains were E. coli strains harboring blaCTX-M-14 on a plasmid obtained in this study. The recipient strains used were either E. coli ML4909 (45), which is lactose non-degrading and resistant to sodium azide, or E. coli ML4903 (46), which is lactose degrading and resistant to rifampicin.

Transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar plates (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with cefotaxime at 4 mg/L (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, St. Louis, MO, USA) and sodium azide at 100 mg/L (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) or rifampicin at 100 mg/L (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation). The presence of the plasmid carrying blaCTX-M-14 in transconjugants was confirmed by PCR (23). Moreover, we calculated conjugation frequency by dividing the number of transconjugants (CFU/mL) by the number of recipient bacteria (CFU/mL). For strains in which transconjugants were not obtained, we repeated the experiment three times under the same conditions to ensure accuracy.

RESULTS

WGS of E. coli harboring blaCTX-M-14

We focused on the plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 commonly observed in E. coli strains belonging to ST131-H30 and other STs. Initially, 273 isolates harboring blaCTX-M-9-group were selected from an original collection of 329 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates. From these, 79 strains, with no redundant isolation year and plasmid Inc group, were selected for draft WGS (Table S1). The mean sequence depth of these assembled genomes was 38× (standard deviation: SD, 26×), and the mean N50 was 97,166 bp (SD, 42,921 bp) (Table S1).

Among the 79 strains, 43 carried blaCTX-M-14 and were classified into 21 STs and 19 fimH types. Eleven of these strains belonged to ST131: seven in H30, three in H41, and one in H27.

From the 43 strains with blaCTX-M-14, we selected 19 strains with diverse combinations of ST, fimH type, and plasmid Inc group for full-length genome sequencing (Table 1; Table S2). These selected strains belonged to 12 STs and 12 fimH types. The mean sequence depth for long-read sequencing was 134× (SD, 69×).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the genetic lineages and the position of blaCTX-M-14 in the E. coli strains (n = 19) in this study

| Strain name | Isolation year | Host ST | Host fimH type | Location of blaCTX-M-14/plasmid name | Inc group [pST] | Length (bp) | Genes located surrounding blaCTX-M-14a | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUM1223 | 1997 | 405 | fimH29 | pMTY1223_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 70,302 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135724 |

| TUM1226 | 1997 | 68 | fimH49 | pMTY1226_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 70,302 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135721 |

| TUM1586 | 2002 | 354 | fimH58 | pMTY1586_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 72,746 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135716 |

| TUM1880 | 2003 | 297 | fimH26 | pMTY1880_IncFII | IncFII [F35:A-:B-] | 70,737 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135707 |

| TUM2802 | 2006 | 131 | fimH30 | pMTY2802_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 72,904 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135693 |

| TUM2830 | 2006 | 131 | fimH41 | pMTY2830_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 70,341 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135687 |

| TUM3755 | 2007 | 752 | fimH24 | pMTY3755_IncFII_2 | IncFII [F35:A-:B-] | 70,758 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP143108 |

| TUM9803 | 2010 | 48 | fimH23 | pMTY9803_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 72,265 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - ∆lamB | CP135673 |

| TUM9975 | 2010 | 131 | fimH30 | pMTY9975_IncFII | IncFII [F2:A-:B-] | 76,366 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135667 |

| TUM2367 | 2005 | 131 | fimH30 | Chromosome | 5,023,218 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135697 | |

| pMTY2367_IncBOKZ | IncB/O/K/Z | 104,860 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135699 | ||||

| TUM2805b | 2006 | 167 | Not determined | pMTY2805_IncBOKZ | IncB/O/K/Z | 101,720 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP128953 |

| TUM2820 | 2006 | 1,638 | fimH167 | pMTY2820_IncBOKZ | IncB/O/K/Z | 102,136 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135689 |

| TUM10008 | 2010 | 93 | fimH30 | pMTY10008_IncBOKZ | IncB/O/K/Z | 87,747 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 | CP135660 |

| TUM14664 | 2014 | 3,075 | fimH54 | pMTY14664_IncBOKZ | IncB/O/K/Z | 128,936 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 | CP135650 |

| TUM17543 | 2016 | 12 | fimH106 | pMTY17543_IncBOKZ | IncB/O/K/Z | 90,712 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 | CP135645 |

| TUM1857 | 2003 | 131 | fimH27 | Chromosome | 5,199,107 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135709 | |

| TUM11356 | 2012 | 131 | fimH41 | Chromosome | 4,963,886 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 | CP135656 | |

| pMTY11356_IncF | IncF [F1:A2:B20] | 160,382 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 | CP135657 | ||||

| TUM13064 | 2012 | 131 | fimH30 | Chromosome | 5,273,163 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135653 | |

| TUM14668 | 2014 | 131 | fimH41 | Chromosome | 4,829,602 | ISEcp1 - blaCTX-M-14 - IS903 - ∆tonB | CP135646 |

The genes located within the ISEcp1-mediated transposable unit flanked by direct repeat sequences were listed.

Data previously published by Ikegaya et al. (23).

Location of blaCTX-M-14 and structural characteristics of the plasmid determined by full-length WGS

Among the 19 isolates, 9 strains possessed IncFII plasmids harboring blaCTX-M-14 (Table 1). Six strains carried blaCTX-M-14 on IncB/O/K/Z plasmids, and one of these strains, TUM2367, also had blaCTX-M-14 on the chromosome. Another strain carried the gene on both the chromosome and the IncF [F1:A2:B20] plasmid. The remaining three strains carried blaCTX-M-14 only on the chromosome.

IncFII plasmid

We initially compared the complete genome sequences of the IncFII plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 from nine strains (Fig. S2). In all plasmids, ISEcp1 was located upstream of blaCTX-M-14. Eight of these plasmids had highly similar structures with 93%–100% similarity in full-length nucleotide sequences, and a partial gene encoding maltoporin LamB (∆lamB) was located downstream of blaCTX-M-14. Although the remaining plasmid, pMTY9975_IncFII, shared a similar nucleotide sequence in a 53 kb region of its 76 kb total length, the region flanking blaCTX-M-14 was different. Immediately downstream of blaCTX-M-14 in pMTY9975_IncFII was IS903 and a partial gene encoding a TonB-dependent receptor (∆tonB).

We searched the public database using BLAST for plasmids with high similarity to pMTY2802_IncFII, which was carried by E. coli ST131-H30 TUM2802 isolated in 2006. We found 24 plasmids with a query cover value over 95%, including pHK01, an epidemic plasmid reported in China in 2004 (47–49). Among these 24 plasmids, we selected those with high structural similarity to pMTY2802_IncFII and pHK01 and possessed by bacterial species other than E. coli to compare the genetic structure of these plasmids in detail (Fig. 1). The entire structures of pEG356 in Shigella sp. (50) and pKpn1693-CTX-M in Klebsiella sp. (51) were highly similar to pMTY2802_IncFII and pHK01. However, the ESBL gene on pEG356 and pKpn1693-CTX-M was blaCTX-M-24 not blaCTX-M-14.

IncB/O/K/Z plasmid

Subsequently, we compared the IncB/O/K/Z plasmids with blaCTX-M-14 possessed by six strains (Fig. S3). In all these plasmids, blaCTX-M-14 was flanked by ISEcp1 upstream and IS903 downstream. The sequence similarity of their plasmid backbones ranged from 76% to 96%. These plasmids were categorized into two types based on the location of blaCTX-M-14 relative to the rep gene: A type, where blaCTX-M-14 was about 25 kb from rep, and B type, where blaCTX-M-14 was located 60–100 kb from rep. Additionally, all A-type plasmids had a ΔtonB gene downstream of IS903, whereas B-type plasmids did not.

In the public databases, only two E. coli plasmids, pB16EC0986-2 and pKKo003_1, were structurally similar to the A-type pMTY2367_IncBOKZ with query cover values above 90%. Sequence similarities of pB16EC0986-2 and pKKo003_1 to pMTY2367_IncBOKZ were 97% and 94%, respectively. Although blaCTX-M-14 was located approximately 25 kb from the rep gene in both plasmids, the upstream ISEcp1 was partly deleted (ΔISEcp1) (Fig. 2A). In pKKo003_1, an inversion of a 2,303 bp region around blaCTX-M-14 was also observed.

For the B-type plasmid pMTY10008_IncBOKZ, a search resulted in 37 plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 with more than 90% query cover, including the epidemic plasmid pCT, detected in the United Kingdom in 2004 (52, 53). We selected the plasmids with the highest query cover from bacterial species other than E. coli and compared their structures with those of pMTY10008_IncBOKZ and pCT (Fig. 2B). These IncB/O/K/Z plasmids had a conserved backbone structure, and blaCTX-M-14 was consistently located approximately 63–104 kb from the rep gene.

Conjugation of plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14

All the IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 from the 16 strains were successfully transferred via conjugation to the E. coli recipient strains. The conjugation frequency of the IncFII plasmids ranged from 8.0 × 10−6 to 9.2 × 10−3, and those of the IncB/O/K/Z plasmids ranged from 1.9 × 10−6 to 5.7 × 10−3. For the strain TUM11356 possessing blaCTX-M-14 on the IncF [F1:A2:B20] plasmid, no transconjugants were obtained. Analysis of the transfer (tra) operon of this IncF plasmid revealed an insertion of IS1G and deletions of traA, traF, traN, trbC, and trbE compared to the tra operon of the conjugative IncFII plasmid, pMTY2802_IncFII (Fig. S4).

Relationship between plasmid type and clade of host E. coli ST131-H30 strains

We focused on ST131-H30 strains and conducted core-genome SNP-based phylogenetic analysis using complete genome sequences of the 4 strains in our collection (TUM2367, TUM2802, TUM9975, and TUM13064) and 141 strains from public databases (Fig. S1). The strains from the public database were isolated in 20 countries across Asia, Europe, North America, Africa, and Australia between 2002 and 2021 (Fig. S5). These 145 ST131-H30 strains were classified into three previously reported clades: clade C0 (n = 2), C1 (n = 94), and C2 (n = 49) (Fig. S5). All strains except CCUG 73778 and CD306, regardless of geographic location of isolation, possessed QRDR mutations in gyrA and parC, resulting in amino acid substitutions of Ser-83-Leu and Asp-87-Asn in GyrA, and Ser-80-Ile and Glu-84-Gly/Val in ParC. Of all 145 strains, 55 carried blaCTX-M-14. Five clade C1 strains and one clade C2 strain possessed blaCTX-M-14 on IncFII plasmids. Five of these were highly similar to pMTY2802_IncFII with a query cover of 94%–100%, except for pMTY9975_IncFII harbored by the clade C1 strain (Fig. S6A). Additionally, three C1 and four C2 strains carried blaCTX-M-14 on IncB/O/K/Z plasmids. Six of these IncB/O/K/Z plasmids, except for pMTY2367_IncBOKZ, were similar to B-type pMTY10008_IncBOKZ with a query cover of 73%–86% and also carried blaCTX-M-14 at the same position on the plasmids (Fig. S6B).

Characterization of subclades in E. coli ST131-H30 clade C1

We conducted a molecular phylogenetic and molecular clock analysis of 96 strains of clades C0 and C1 to determine the molecular characteristics of each subclade and the divergence dates of these subclades (Fig. 3). Moreover, clade C0 strains were included to validate the molecular clock analysis. Clade C0 consisted of two strains, CCUG 73778 and CD306, which did not harbor QRDR mutations. Therefore, it was inferred that the timing of the divergence of clade C1 from clade C0 approximately coincided with that of the emergence of the QRDR mutations.

Clade C1 diverged into eight distinct subclades. The estimated divergence date of clade C1 from clade C0 was around 1983 [95% highest posterior density (HPD), 1977–1988]. Among the C1 subclades, subclades 1, 2, 3, and 8 did not contain clusters of strains with blaCTX-M genes. In contrast, subclades 4–7 included clusters of strains harboring blaCTX-M-14 or blaCTX-M-27. Notably, subclades 4–8 were estimated to have diverged from their common ancestor around 1992 (HPD, 1988–1996). Moreover, all the 34 strains in subclade 5 possessed blaCTX-M-14 on their chromosomes. This subclade likely emerged approximately in 1999 (HPD, 1995–2002). Meanwhile, 28 out of the 29 strains in subclades 6 and 7 possessed blaCTX-M-27, which is a single-nucleotide variant of blaCTX-M-14. Moreover, blaCTX-M-27 was predominately carried on IncF [F1:A2:B20] plasmids (n = 25) (Fig. S5).

Location and surrounding structures of blaCTX-M-14 on the chromosome in ST131-H30 clade C1 strains

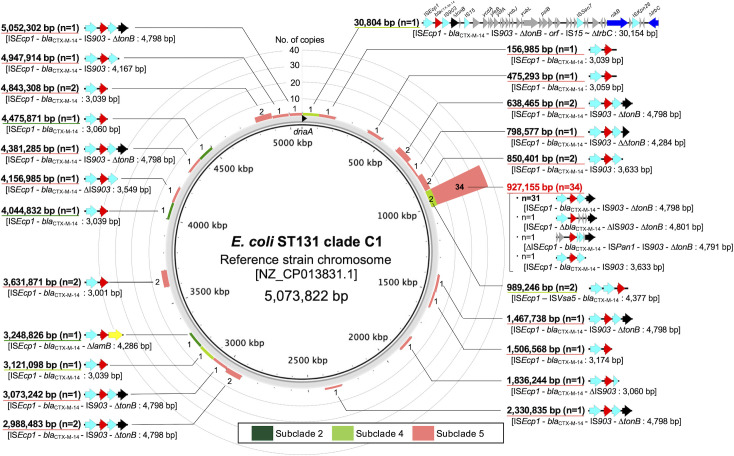

To investigate whether C1-subclade 5 strains had acquired the chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 genes in a single acquisition event and subsequently inherited them by progeny strains, we analyzed the chromosomal location and surrounding genetic structure of blaCTX-M-14 in these strains. We also investigated the genetic environment of chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 in strains from other subclades for comparison. Forty strains from subclades 2, 4, or 5 possessed one to five copies of chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 with all these genes (Fig. S5), except in STO_Bone8 (which had ∆ISEcp1), containing intact ISEcp1 sequences upstream and conserved right and left inverted repeat sequences for the ISEcp1-mediated transposable units (Table S3). Using the genome sequence of strain CD306 (GenBank accession number NZ_CP013831) as a reference, we analyzed the regions flanked by direct repeat (DR) sequences for unit length and chromosomal location as ISEcp1-mediated transposable units. The lengths of these transposable units ranged from 3,001 to 4,801 bp. For those missing downstream DRs (such as TUM2367, F16EC0593-1, and E17EC0383-2), the unit and chromosome boundaries were analyzed, revealing unit lengths from 3,633 to 30,154 bp. The ISEcp1-mediated transposable units were located at 24 different positions on the chromosome, with 34 subclade 5 isolates consistently having an integration at position bp 927155 (Fig. 4). The transposable units of 31 out of these 34 subclade C5 isolates shared a common 4,798 bp structure comprising ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-14-IS903-∆tonB.

Fig 4.

Chromosomal location of the ISEcp1-mediated transposable units with blaCTX-M-14 in E. coli ST131-H30 clade C1 strains using the genome sequence of strain CD306 (GenBank accession number NZ_CP013831) as the reference and the surrounding structure of blaCTX-M-14 in the transposable units. The ISEcp1-mediated transposable unit is defined as the region inside direct repeats adjacent to inverted repeat left or inverted repeat right. For strains in which ISEcp1 was disrupted or the downstream DR was not intact, the boundary was defined as the site where a sequence matching the chromosomal nucleotide sequence of the reference genome appeared. Block arrows indicate confirmed or putative ORFs and their orientations. Arrow size is proportional to the predicted ORF length. The meanings of the arrow colors are as follows: red, blaCTX-M-14; yellow, ∆lamB; black, ∆tonB; cyan, transposase genes; blue, conjugal transfer genes; green, replication initiation protein genes. Putative, hypothetical, and unknown genes are represented by gray arrows.

The remaining three strains (STO_Bone8, E17EC0383-1, and F16EC0593-1) had IS insertions or inversions in the transposable unit but otherwise shared a common structure. Additionally, 14 out of the 34 subclade 5 isolates harbored one to four additional ISEcp1-mediated transposable units containing blaCTX-M-14 at various other positions, although the insertion positions differed in all but one pair of strains with high overall genetic similarity (E16EC0458-5 and E16EC0945-1). The positions of insertion of ISEcp1-mediated transposable units with blaCTX-M-14 were also diverse among subclade 2 and 4 strains.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we detected the IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 in diverse genetic lineages of E. coli from the 2000s. Molecular phylogenetic analysis indicated that ST131-H30 clade C1 strains acquired a plasmid carrying blaCTX-M-14, followed by the integration of blaCTX-M-14 into the chromosome, resulting in the emergence of C1-subclade 5, which universally harbors chromosomal blaCTX-M-14.

blaCTX-M-14 originated from the chromosomal β-lactamase gene of Kluyvera georgiana (blaKLUY) (54) and is hypothesized to have spread horizontally to other Enterobacterales mediated by IS elements such as ISEcp1 and conjugative plasmids (10). Previous studies have reported that plasmids in various Inc groups carried blaCTX-M-14 using PCR typing methods (55, 56). Notably, IncF plasmids, such as pHK01, were prevalent in China and Korea (47–49, 57), while IncK plasmids, such as pCT, were prevalent in Spain and the UK (53, 58–60). In this study, IncFII plasmids similar to pHK01 and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids similar to pCT were detected in E. coli belonging to diverse genetic lineages isolated between 1997 and 2016 (Fig. S2 and S3). Therefore, these plasmids likely contributed to the spread of blaCTX-M-14 in Japan as well. We confirmed that IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 can transfer horizontally into E. coli, consistent with previous reports (61). Additionally, genomic analysis identified plasmids with high similarity to pMTY2802_IncFII or pMTY10008_IncBOKZ, found in E. coli strains in Japan in this study, within E. coli, Shigella sonnei, and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from various countries (Fig. 1 and 2). These plasmids are thus expected to spread by conjugation not only to E. coli but also to other Enterobacteriaceae. In Japan, Korea, and Spain, E. coli strains harboring blaCTX-M isolated from patients in the 2000s belonged to highly diverse genetic lineages, including ST131 (57, 62, 63), likely due to the horizontal transfer of the gene via these plasmids. In contrast, transconjugants for the IncF plasmid with blaCTX-M-14, pMTY11356_IncF, were not obtained, and conjugal transfer-related genes traA, traF, traN, trbE, and trbC were deleted (Fig. S4). Notably, TraF is a 26-kDa periplasmic protein required for the F-pilus extension (64), and it has been reported that the traF knockout results in the failure to obtain a transconjugant (65). We hypothesize that the deletion of traF is responsible for the failure of conjugative transmission in pMTY11356_IncF.

In E. coli ST131-H30, the IncF plasmid is linked to blaCTX-M, such as IncF [F2:A1:B-] with blaCTX-M-15 and IncF [F1:A2:B2] with blaCTX-M-27 (16, 66, 67), although literature about a plasmid carrying blaCTX-M-14 has been limited. Our plasmid analysis of 145 E. coli ST131-H30 strains suggested that IncFII plasmids similar to pMTY2802_IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids similar to pMTY10008_IncBOKZ likely played important roles in the acquisition of blaCTX-M-14 in ST131-H30.

The evolutionary process leading to the creation of the E. coli ST131-H30 lineage harboring blaCTX-M has been investigated in several previous studies using molecular clock analysis. It was predicted that E. coli ST131-H30 emerged around 1980 (95% HPD, 1973–1986), acquired fluoroquinolone resistance, and later diverged into clades C1 and C2 around 1987 (95% HPD, 1983–1992), subsequently acquiring blaCTX-M (6, 7). To investigate the further evolution within ST131-H30 clade C1, we performed molecular phylogenetic and molecular clock analysis using complete genomes and estimated the divergence date of the subclades (Fig. 3). Initially, we estimated that QRDR mutations occurred around 1989 in clade C1. These mutations conferred fluoroquinolone resistance and provided a selective advantage under antimicrobial use for ST131-H30 strains worldwide. As this estimated date was consistent with previous reports (6), the analysis method used in this study seems valid. Among the eight subclades of clade C1, most strains in subclades 4–8 harbored blaCTX-M-14 or blaCTX-M-27. Assuming that blaCTX-M-27 evolved from blaCTX-M-14, it was inferred that the common ancestor of these subclades acquired blaCTX-M-14 around 1993 (1989–1996). This estimation appears reasonable, as blaCTX-M-14 was first reported in 1995 from Shigella spp. isolated from a patient in South Korea (68).

We also focused on subclade 5, which harbored chromosomal blaCTX-M-14. All 34 strains of subclade 5 had a transposable unit containing the ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-14-IS903-∆tonB structure at the same position on the chromosome (bp 927155 of the genomic sequence of strain CD306). Therefore, this ISEcp1-mediated transposable unit was acquired by a single transposition event in the common ancestral strain of these isolates. Considering the period when subclade 5 was formed, it was estimated that this event took place no later than 1999.

Furthermore, we focused on the genetic structure of IS903-∆tonB, situated downstream of blaCTX-M-14, to identify the plasmid from which the chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 in subclade 5 originated. Among the plasmids analyzed in this study, only one each of the A-type IncB/O/K/Z plasmid (pMTY2367_IncBOKZ) and the IncFII plasmid (pMTY9975_IncFII) possessed intact ISEcp1 and IS903-∆tonB. However, drawing a definitive conclusion regarding their origin proved challenging, as only one of the strains within ST131 (TUM2367 and TUM9975) carried each of these plasmids.

Fourteen of the 34 isolates harbored similar transposable units at different chromosomal positions in addition to the bp 927155 position. However, the insertion positions were diverse, and the length downstream of blaCTX-M-14 was equal to or less than that of the transposable unit at the bp 927155 position. Therefore, multiple copies of blaCTX-M-14 on the chromosome may have arisen by replicative transposition of the ISEcp1-mediated unit following an integration at the bp 927155 position. Moreover, chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 was located in the vicinity of dnaA, and the copy number of genes was amplified using either copy-and-paste or tandem amplification methods to adjust the transcript level of blaCTX-M-14 and extend the resistance spectrum (19). Additionally, transposition of blaCTX-M-14 to the chromosome among subclade 5 strains may allow these strains to stably possess the gene. Moreover, strains with chromosomal blaNDM-5 were more stable in gene inheritance for at least 30 days than those with the gene on a plasmid (69).

In a subclade of E. coli ST38 with blaOXA-48, transfer of the composite transposon containing blaOXA-48 from the plasmid to the chromosome resulted in stable maintenance of the resistance gene with a reduced fitness cost (70). About a quarter of the 115 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae bloodstream isolates belonging to ST307 or ST48 from six hospitals in Korea had blaCTX-M on their chromosomes, suggesting the advantage of chromosomal location of the resistance genes for stable transmission in clinical settings (71).

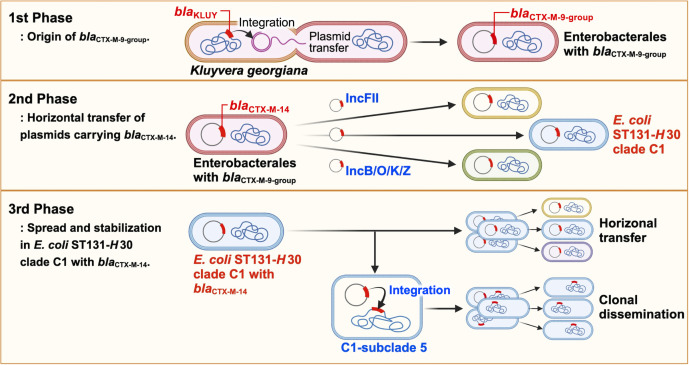

Overall, we conceptualized a blaCTX-M-14 spreading process consisting of the following three phases (Fig. 5). In the first phase, blaKLUY on the chromosome of K. georgiana was transposed to a plasmid and horizontally transferred to other Enterobacterales via conjugation. In the second phase, blaCTX-M-14 was horizontally transferred to E. coli of diverse genetic lineages, including ST131-H30, mediated by plasmids, such as IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids, around 1993. In the third phase, E. coli ST131-H30 strains with blaCTX-M-14 disseminated while retaining these plasmids. During this process, blaCTX-M-14 in an E. coli ST131-H30 C1 strain has been integrated into the chromosome by ISEcp1-mediated transposition. This process may facilitate the spread of blaCTX-M-14 with stable retention, followed by the creation of C1-subclade 5 around 1999. In this study, there are five limitations. First, it is a retrospective study using stored E. coli strains with blaCTX-M-14 isolated before 2016. The collection criteria were not standardized. Therefore, there is a potential for bias regarding the geographic regions and sources of the isolates. Second, only 19 out of the 329 strains underwent full-length WGS. Consequently, the findings may not fully represent the characteristics of all plasmids harboring blaCTX-M-14. Third, this study did not include the most recent isolates from Japan, which may affect the relevance of the findings to current conditions. Fourth, the origin and mechanism of blaCTX-M-14 acquisition by IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids remain unclear. Fifth, 32 of the 34 subclade 5 isolates in the ST131-H30 clade C1 were from South Korea. Despite this, we used all full-length genome sequences of E. coli ST131-H30 in public databases.

Fig 5.

The dissemination and adaptive evolution scenario of blaCTX-M-14. The illustration was created with BioRender.com.

Conclusion

Our study revealed the significant role of IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids in the global spread of blaCTX-M-14 across diverse bacterial species, including E. coli ST131-H30. Furthermore, the ST131-H30 clade C1 strains likely disseminated while carrying plasmids containing blaCTX-M-14, leading to the emergence of a strain with chromosomal integration of blaCTX-M-14, thereby contributing to its spread. Our findings highlight the critical influence of horizontal plasmid transmission and chromosomal integration, especially in pandemic lineages, on the dissemination and evolution of antimicrobial-resistant strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (grant numbers: H30-Shokuhin-Ippan-006 and 21KA1004), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) to Y.I. (grant number JP18K08452), and the Project Research Grant No. 22-7 of Toho University School of Medicine. K.K. is a recipient of the BIKEN Taniguchi Scholarship.

The authors thank Enago for the English language review.

Contributor Information

Yoshikazu Ishii, Email: ishiiyo@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.

Alessandra Carattoli, Universita degli studi di roma La Sapienza, Rome, Italy.

DATA AVAILABILITY

WGS data have been deposited in the GenBank database under the BioProject accession numbers PRJNA984451, PRJNA984747, and PRJNA1019817. The GenBank accession numbers assigned to each WGS data are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00817-24.

The strain selection process for comparative analysis of plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 and molecular phylogenetic analysis of ST131-H30 used in this study.

Structural comparison of IncFII plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 possessed by E. coli in diverse genetic lineages in this study.

Structural comparison of IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 possessed by E. coli in diverse genetic lineages in this study.

Structural comparison of the IncF plasmid carrying blaCTX-M-14 and the conjugative IncFII plasmid.

Strain information and genetic sublineages of E. coli ST131-H30 in this study and public databases used for molecular phylogenetic analysis.

Structure comparison of IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 harbored by ST131-H30 strains.

Whole genome sequencing-analyzed E. coli strains with blaCTX-M-9 group in our strain collection.

Full-length genome sequencing-analyzed E. coli strains with blaCTX-M-14 in our strain collection.

Insertion location and surrounding structure of blaCTX-M-14 on the chromosome of a reference strain.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Caniça MM, Park Y-J, Lavigne J-P, Pitout J, Johnson JR. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:273–281. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Bertrand X, Madec J-Y. 2014. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:543–574. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00125-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B, Clabots C, Roberts PL, Billig M, Riddell K, Rogers P, Qin X, Butler-Wu S, et al. 2013. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis 207:919–928. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Stanton-Cook M, Skippington E, Totsika M, Forde BM, Phan M-D, Gomes Moriel D, Peters KM, Davies M, Rogers BA, Dougan G, Rodriguez-Baño J, Pascual A, Pitout JDD, Upton M, Paterson DL, Walsh TR, Schembri MA, Beatson SA. 2014. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:5694–5699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322678111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ben Zakour NL, Alsheikh-Hussain AS, Ashcroft MM, Khanh Nhu NT, Roberts LW, Stanton-Cook M, Schembri MA, Beatson SA. 2016. Sequential acquisition of virulence and fluoroquinolone resistance has shaped the evolution of Escherichia coli ST131. mBio 7:e00347-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00347-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Pankhurst L, De Maio N, Moore CE, Sebra R, Turner P, Anson LW, Kasarskis A, Batty EM, Kos V, Wilson DJ, Phetsouvanh R, Wyllie D, Sokurenko E, Manges AR, Johnson TJ, Price LB, Peto TEA, Johnson JR, Didelot X, Walker AS, Crook DW, Modernizing Medical Microbiology Informatics Group (MMMIG) . 2016. Evolutionary history of the global emergence of the Escherichia coli epidemic clone ST131. mBio 7:e02162. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02162-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. 2017. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2145–2155. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Humeniuk C, Arlet G, Gautier V, Grimont P, Labia R, Philippon A. 2002. β-lactamases of Kluyvera ascorbata, probable progenitors of some plasmid-encoded CTX-M types. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3045–3049. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3045-3049.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cantón R, González-Alba JM, Galán JC. 2012. CTX-M enzymes: origin and diffusion. Front Microbiol 3:110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Novick RP. 1987. Plasmid incompatibility. Microbiol Rev 51:381–395. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.381-395.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Couturier M, Bex F, Bergquist PL, Maas WK. 1988. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol Rev 52:375–395. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.3.375-395.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kamruzzaman M, Iredell J. 2019. A ParDE-family toxin antitoxin system in major resistance plasmids of Enterobacteriaceae confers antibiotic and heat tolerance. Sci Rep 9:9872. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46318-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phan MD, Forde BM, Peters KM, Sarkar S, Hancock S, Stanton-Cook M, Ben Zakour NL, Upton M, Beatson SA, Schembri MA. 2015. Molecular characterization of a multidrug resistance IncF plasmid from the globally disseminated Escherichia coli ST131 clone. PLoS One 10:e0122369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyd DA, Tyler S, Christianson S, McGeer A, Muller MP, Willey BM, Bryce E, Gardam M, Nordmann P, Mulvey MR. 2004. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 92-kilobase plasmid harboring the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase involved in an outbreak in long-term-care facilities in Toronto, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3758–3764. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3758-3764.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kondratyeva K, Salmon-Divon M, Navon-Venezia S. 2020. Meta-analysis of pandemic Escherichia coli ST131 plasmidome proves restricted plasmid-clade associations. Sci Rep 10:36. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56763-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsuo N, Nonogaki R, Hayashi M, Wachino J-I, Suzuki M, Arakawa Y, Kawamura K. 2020. Characterization of blaCTX-M-27/F1:A2:B20 plasmids harbored by Escherichia coli sequence type 131 sublineage C1/H30R isolates spreading among elderly Japanese in nonacute-care settings. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00202-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00202-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayashi M, Matsui M, Sekizuka T, Shima A, Segawa T, Kuroda M, Kawamura K, Suzuki S. 2020. Dissemination of IncF group F1:A2:B20 plasmid-harbouring multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST131 before the acquisition of blaCTX-M in Japan. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 23:456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoon E-J, Choi YJ, Kim D, Won D, Choi JR, Jeong SH. 2022. Amplification of the chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 gene in Escherichia coli expanding the spectrum of resistance under antimicrobial pressure. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0031922. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00319-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamamoto K, Ueda S, Toyosato T, Yamamoto Y, Hirai I. 2016. High prevalence of chromosomal blaCTX-M-14 in Escherichia coli isolates possessing blaCTX-M-14. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2582–2584. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00108-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hamamoto K, Tokunaga T, Yagi N, Hirai I. 2020. Characterization of blaCTX-M-14 transposition from plasmid to chromosome in Escherichia coli experimental strain. Int J Med Microbiol 310:151395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2020.151395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matsumura Y, Johnson JR, Yamamoto M, Nagao M, Tanaka M, Takakura S, Ichiyama S, Matsumura Y, Yamamoto M, Nagao M. 2015. CTX-M-27- and CTX-M-14-producing, ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli of the H30 subclonal group within ST131 drive a Japanese regional ESBL epidemic. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:1639–1649. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ikegaya K, Aoki K, Komori K, Ishii Y, Tateda K. 2023. Analysis of the stepwise acquisition of blaCTX-M-2 and subsequent acquisition of either blaIMP-1 or blaIMP-6 in highly conserved IncN-pST5 plasmids. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance 5. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlad106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu L, Ensor V, Gossain S, Nye K, Hawkey P. 2005. Rapid and simple detection of blaCTX-M genes by multiplex PCR assay. J Med Microbiol 54:1183–1187. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46160-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods 63:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. 2013. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D36–D42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. 2018. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun 9:5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. 2005. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Coster W, D’Hert S, Schultz DT, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. 2018. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 34:2666–2669. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, Cuomo CA, Zeng Q, Wortman J, Young SK, Earl AM. 2014. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanizawa Y, Fujisawa T, Kaminuma E, Nakamura Y, Arita M. 2016. DFAST and DAGA: web-based integrated genome annotation tools and resources. Biosci Microbiota Food Health 35:173–184. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.16-003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. 2011. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Earl D, Bradnam K, St John J, Darling A, Lin D, Fass J, Yu HOK, Buffalo V, Zerbino DR, Diekhans M, et al. 2011. Assemblathon 1: a competitive assessment of de novo short read assembly methods. Genome Res 21:2224–2241. doi: 10.1101/gr.126599.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. 2012. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Didelot X, Wilson DJ. 2015. ClonalFrameML: efficient inference of recombination in whole bacterial genomes. PLoS Comput Biol 11:e1004041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchêne S, Fourment M, Gavryushkina A, Heled J, Jones G, Kühnert D, De Maio N, Matschiner M, Mendes FK, Müller NF, Ogilvie HA, du Plessis L, Popinga A, Rambaut A, Rasmussen D, Siveroni I, Suchard MA, Wu C-H, Xie D, Zhang C, Stadler T, Drummond AJ. 2019. BEAST 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 15:e1006650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma L, Ishii Y, Ishiguro M, Matsuzawa H, Yamaguchi K. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding Toho-2, a class A β-lactamase preferentially inhibited by tazobactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:1181–1186. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.5.1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ishii Y, Ohno A, Taguchi H, Imajo S, Ishiguro M, Matsuzawa H. 1995. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding a cefotaxime-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase isolated from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:2269–2275. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.10.2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ho PL, Lo WU, Wong RCW, Yeung MK, Chow KH, Que TL, Tong AHY, Bao JYJ, Lok S, Wong SSY. 2011. Complete sequencing of the FII plasmid pHK01, encoding CTX-M-14, and molecular analysis of its variants among Escherichia coli from Hong Kong. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:752–756. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ho PL, Lo WU, Yeung MK, Li Z, Chan J, Chow KH, Yam WC, Tong AHY, Bao JYJ, Lin CH, Lok S, Chiu SS. 2012. Dissemination of pHK01-like incompatibility group IncFII plasmids encoding CTX-M-14 in Escherichia coli from human and animal sources. Vet Microbiol 158:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ho PL, Yeung MK, Lo WU, Tse H, Li Z, Lai EL, Chow KH, To KK, Yam WC. 2012. Predominance of pHK01-like incompatibility group FII plasmids encoding CTX-M-14 among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli in Hong Kong, 1996–2008. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73:182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nguyen NTK, Ha V, Tran NVT, Stabler R, Pham DT, Le TMV, van Doorn HR, Cerdeño-Tárraga A, Thomson N, Campbell J, Nguyen VMH, Tran TTN, Pham MV, Cao TT, Wren B, Farrar J, Baker S. 2010. The sudden dominance of blaCTX-M harbouring plasmids in Shigella spp. circulating in Southern Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Liu J, Hu X, Nie T, Yang X, Wang X, Li C, You X. 2020. Characterization of a hypervirulent multidrug-resistant ST23 Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying a blaCTX-M-24 IncFII plasmid and a pK2044-like plasmid. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 22:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Teale CJ, Barker L, Foster AP, Liebana E, Batchelor M, Livermore DM, Threlfall EJ. 2005. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase detected in E coli recovered from calves in Wales. Vet Rec 156:186–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cottell JL, Webber MA, Coldham NG, Taylor DL, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Hauser H, Thomson NR, Woodward MJ, Piddock LJV. 2011. Complete sequence and molecular epidemiology of IncK epidemic plasmid encoding blaCTX-M-14. Emerg Infect Dis 17:645–652. doi: 10.3201/eid1704.101009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Olson AB, Silverman M, Boyd DA, McGeer A, Willey BM, Pong-Porter V, Daneman N, Mulvey MR. 2005. Identification of a progenitor of the CTX-M-9 group of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases from Kluyvera georgiana isolated in Guyana. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:2112–2115. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.2112-2115.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liao X-P, Xia J, Yang L, Li L, Sun J, Liu Y-H, Jiang H-X. 2015. Characterization of CTX-M-14-producing Escherichia coli from food-producing animals. Front Microbiol 6:1136. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Marcadé G, Deschamps C, Boyd A, Gautier V, Picard B, Branger C, Denamur E, Arlet G. 2009. Replicon typing of plasmids in Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:67–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim J, Bae IK, Jeong SH, Chang CL, Lee CH, Lee K. 2011. Characterization of IncF plasmids carrying the blaCTX-M-14 gene in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1263–1268. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Valverde A, Cantón R, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Novais A, Galán JC, Alvarado A, de la Cruz F, Baquero F, Coque TM. 2009. Spread of blaCTX-M-14 is driven mainly by IncK plasmids disseminated among Escherichia coli phylogroups A, B1, and D in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5204–5212. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01706-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Navarro F, Mesa R-J, Miró E, Gómez L, Mirelis B, Coll P. 2007. Evidence for convergent evolution of CTX-M-14 ESBL in Escherichia coli and its prevalence. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273:120–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stokes MO, Cottell JL, Piddock LJV, Wu G, Wootton M, Mevius DJ, Randall LP, Teale CJ, Fielder MD, Coldham NG. 2012. Detection and characterization of pCT-like plasmid vectors for blaCTX-M-14 in Escherichia coli isolates from humans, turkeys and cattle in England and Wales. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1639–1644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Partridge SR, Kwong SM, Firth N, Jensen SO. 2018. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 31:e00088-17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00088-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Suzuki S, Shibata N, Yamane K, Wachino J -i., Ito K, Arakawa Y. 2009. Change in the prevalence of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Japan by clonal spread. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:72–79. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oteo J, Diestra K, Juan C, Bautista V, Novais A, Pérez-Vázquez M, Moyá B, Miró E, Coque TM, Oliver A, Cantón R, Navarro F, Campos J, Spanish Network in Infectious Pathology Project (REIPI) . 2009. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Spain belong to a large variety of multilocus sequence typing types, including ST10 complex/A, ST23 complex/A and ST131/B2. Int J Antimicrob Agents 34:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bragagnolo N, Rodriguez C, Samari-Kermani N, Fours A, Korouzhdehi M, Lysenko R, Audette GF. 2020. Protein dynamics in F-like bacterial conjugation. Biomedicines 8:362. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8090362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lento C, Ferraro M, Wilson D, Audette GF. 2016. HDX-MS and deletion analysis of the type 4 secretion system protein TraF from the Escherichia coli F plasmid. FEBS Lett 590:376–386. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Novais A, Pires J, Ferreira H, Costa L, Montenegro C, Vuotto C, Donelli G, Coque TM, Peixe L. 2012. Characterization of globally spread Escherichia coli ST131 isolates (1991 to 2010). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3973–3976. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00475-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Johnson TJ, Danzeisen JL, Youmans B, Case K, Llop K, Munoz-Aguayo J, Flores-Figueroa C, Aziz M, Stoesser N, Sokurenko E, Price LB, Johnson JR. 2016. Separate F-type plasmids have shaped the evolution of the H30 subclone of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. mSphere 1:e00121-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00121-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pai H, Choi EH, Lee HJ, Hong JY, Jacoby GA. 2001. Identification of CTX-M-14 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in clinical isolates of Shigella sonnei, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J Clin Microbiol 39:3747–3749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3747-3749.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sakamoto N, Akeda Y, Sugawara Y, Matsumoto Y, Motooka D, Iida T, Hamada S. 2022. Role of chromosome- and/or plasmid-located blaNDM on the carbapenem resistance and the gene stability in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0058722. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00587-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zongo PD, Cabanel N, Royer G, Depardieu F, Hartmann A, Naas T, Glaser P, Rosinski-Chupin I. 2024. An antiplasmid system drives antibiotic resistance gene integration in carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli lineages. Nat Commun 15:4093. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48219-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yoon E-J, Gwon B, Liu C, Kim D, Won D, Park SG, Choi JR, Jeong SH. 2020. Beneficial chromosomal integration of the genes for CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae for stable propagation. mSystems 5:e00459-20. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00459-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The strain selection process for comparative analysis of plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 and molecular phylogenetic analysis of ST131-H30 used in this study.

Structural comparison of IncFII plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 possessed by E. coli in diverse genetic lineages in this study.

Structural comparison of IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 possessed by E. coli in diverse genetic lineages in this study.

Structural comparison of the IncF plasmid carrying blaCTX-M-14 and the conjugative IncFII plasmid.

Strain information and genetic sublineages of E. coli ST131-H30 in this study and public databases used for molecular phylogenetic analysis.

Structure comparison of IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-14 harbored by ST131-H30 strains.

Whole genome sequencing-analyzed E. coli strains with blaCTX-M-9 group in our strain collection.

Full-length genome sequencing-analyzed E. coli strains with blaCTX-M-14 in our strain collection.

Insertion location and surrounding structure of blaCTX-M-14 on the chromosome of a reference strain.

Data Availability Statement

WGS data have been deposited in the GenBank database under the BioProject accession numbers PRJNA984451, PRJNA984747, and PRJNA1019817. The GenBank accession numbers assigned to each WGS data are provided in Tables S1 and S2.