Abstract

Low dose of dabigatran paradoxically increased thrombin generation through inhibition of protein C activation. Protein S is a co-factor in the activation of protein C. However, the role of protein S in the enhancement of thrombin generation has not been addressed. Firstly, we measured thrombin generation by calibrated automated thrombinography (CAT) and prothrombin fragments 1+2 (F1+2) assays. Secondly, we assessed activated protein C (APC) formation in normal or protein S-deficient plasma spiking with dabigatran. Then, protein C activation was measured. Finally, heavy chain of factor Va (FVa) and its degradation products were detected by western blot. CAT assay showed that 70–141 ng/ml dabigatran paradoxically increased thrombin generation in normal plasma. However, higher concentrations of dabigatran (283 ng/ml) suppressed the level of ETP. F1+2 assay showed the similar results. In protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma, the paradoxical increase in thrombin generation was absent. Level of generated APC was to a similar extent inhibited by dabigatran in normal and protein S-deficient plasma. Low-dose dabigatran inhibited the protein S-dependent inactivation of factor Va. Protein S participated in the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation in normal plasma spiking with low concentrations of dabigatran. Increased thrombin generation at low dabigatran can be explained by reduced thrombin–thrombomodulin mediated APC formation and subsequent reduced FVa inactivation that is protein S-dependent.

Keywords: dabigatran, protein C, protein S, prothrombin fragments 1+2, thrombin generation

Introduction

New oral anticoagulants are widely used to prevent thrombotic events in clinical practice [1]. Thrombin plays a central role in the clotting process by regulating blood coagulation cascade and platelet activation [2]. Hence, thrombin acts as an attractive target for anticoagulation. Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor, and it could overcome the limitations of vitamin K antagonists [3]. Dabigatran inhibits both thrombin and fibrin-bound thrombin through binding to the active site of thrombin [4].

Previous studies demonstrated that dabigatran and melagatran paradoxically increased thrombin generation with thrombin–thrombomodulin present [5,6]. In rat models, melagatran significantly increased thrombin generation leading to rebound hypercoagulability [7]. Kamisato et al.[8] demonstrated that paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation might be due to the reduced degradation of factor Va (FVa) and factor VIIIa (FVIIIa). protein C serves as a native serine protease zymogen under normal physiological conditions and can be activated by the thrombin–thrombomodulin complex [9,10]. FVa was cleaved by activated protein C (APC) at Arg306, Arg506, and Arg679 sites. The Arg306 cleavage requires the presence of protein S [11]. The fragment of FVa307–506 indicates the complete loss of FVa activity [12].

Protein S is a vitamin K-dependent glycoprotein which plays a vital role in the blood coagulation. Protein S exists both in a free form (≈140 nmol/l) and in an inactive form [13]. Protein S functions as a cofactor for the APC and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) pathways. Protein S enhances both the inhibition of FXa generation by TF-FVIIa and the direct inhibition of FXa activity by TFPIα [14]. Furthermore, previous study showed that protein S inhibited FVa and FVIIIa activity in APC-independent manner [15]. Heterozygous protein S deficiency increased the risk of thrombosis. Protein S acts as an important factor of protein C system. However, the role of protein S in the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation has not been well described.

Methods and materials

Agents

Dabigatran and dabigatran-d3 were synthesized at Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada). Normal plasma was obtained from Boatman Biotech (Shanghai, China). Protein S-deficient and protein C-deficient plasmas and free protein S ELISA kit were prepared by HYPHEN BioMed (Oise, France). Recombinant human soluble thrombin–thrombomodulin (rhs-TM) was from R&D Systems (North America) and dissolved in 0.9% NaCl. Monoclonal mouse antihuman FV antibody was from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, Vermont, USA). Monoclonal mouse antihuman IgG and D-Phe-Pro-Arg-chloromethylketone (PPACK) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). PPP regent, FluCa, and thrombin calibrator were purchased from Thrombinoscope BV (Maastricht, The Netherlands). Pefabloc FG was from Pentapharm (Basel, Switzerland). Prothrombin fragment 1+2 (F1+2) ELISA kit was from Dade Behring (Marburg, Germany). Activated protein C-protein C inhibitor complex (aPC-PCI) ELISA kit was from Affinity Biologicals (Ontario, Canada).

Preparation of dabigatran

Dabigatran was dissolved in 1 N HCl and filled up to 1 ml with distilled water. Different volumes of distilled water were added to make final concentrations of dabigatran (0.5, 2, 12, 35, 70, 141, 283 and 566 nmol/ml).

Thrombin generation assay

Calibrated automated thrombogram (CAT) method (Thrombinoscope, Maastricht, The Netherlands) was used to detect thrombin generation according to Morishima's study [16]. Normal, protein S-deficient, and protein C-deficient plasmas (76 μl) were spiked with different concentrations (2 μl) of dabigatran (n = 9) in the presence of rhs-TM (2 μl). In control group, dabigatran was replaced with the same volume of solvent of dabigatran. Then, PPP reagent (20 μl) was added to the plasma. After incubation at 37 °C for 5 min, plasma with dabigatran was added to the thrombin generation wells and plasma without dabigatran was added to the thrombin calibrator wells. Flu-buffer incubated at 37 °C for 5 min and Flu-substrate was mixed to generate FluCa. FluCa was automatically added to each well, and results were read by a Fluoroskan Ascent fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The final concentrations of tissue factor, phospholipids, fluorogenic substrate, and CaCl2 were 5 pmol/l, 4 μmol/l, 417 μmol/l, and 16.7 mmol/l. Thrombin generation curves were generated by the Thrombinoscope software (Thrombinoscope BV).

Prothrombin fragment 1+2 assay

F1+2 is a marker of thrombin generation. Thrombin generation was induced according to the method described above with minor modifications. Normal, protein S-deficient, and protein C-deficient plasmas (76 μl) were spiked with different concentrations (2 μl) of dabigatran (n = 6) in the presence of rhs-TM (2 μl). The control group contained the appropriate vehicles. Plasma was defibrinated using 2 μl PefablocFG (final concentration of 6 mg/ml). The reaction was started by adding Fluo-buffer containing HEPES, calcium chloride and DMSO. PPACK was used to stop the coagulation reaction after 12 min. The mixture (120 μl) was transferred to microtiter plates and F1+2 assessed following the manufacturer's instructions. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was between 3.6 and 5.5% and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was between 4.4 and 11.2%.

Protein C activation assay

Protein C activation was detected by an aPC-PCI ELISA kit. Thrombin generation was induced as above and the reaction was stopped 15 min after the time to peak in the thrombin generation assay by adding 13 μl of 0.5 mol/l sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.3). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was between 3.6 and 5.5% and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was between 4.4 and 11.2%.

Western blot analysis

Thrombin generation was induced as described above in plasma without Fluca. Several reaction time points were set up in protein S-deficient plasma and normal plasma spiked with or without 70 ng/ml dabigatran according to CAT results. The reaction was stopped with 13 μl of 0.5 mol/l sodium citrate buffer (pH4.3). FVaHC and its degradation product FVa307–506 were detected by factor V antibody (2.5 μg/ml). IgG (dilution 1 : 1000) was used as the loading control.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was completed with Stata 14.0. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired parametric t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test was used for data analysis. P less than 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

Results

Effect of dabigatran on thrombin generation

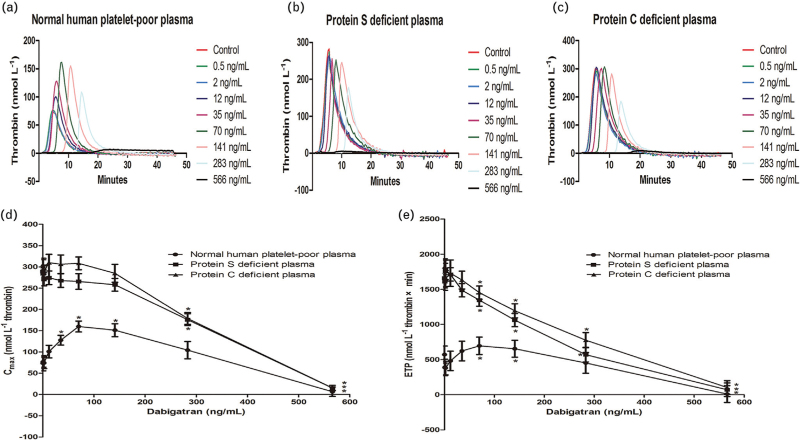

We measured thrombin generation by CAT assay in plasma spiking with different concentrations of dabigatran (n = 9). Fig. 1a showed that there was a gradual dose-dependent increase of thrombin generation in normal plasma. Interestingly, the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation was absent in protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma (Fig. 1b and c). We analysed important indices including peak thrombin generation (Cmax) and endogenous thrombin potential (ETP) from CAT assay. Low concentrations of dabigatran (35–141 ng/ml) significantly increased Cmax in normal plasma (Fig. 1d). In normal plasma spiking with 70–141 ng/ml dabigatran, there was a gradual dose-dependent increase of ETP (Fig. 1e). Higher concentrations of dabigatran (283 ng/ml) suppressed ETP in normal, Protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma (104.28 ± 20.28, 175.86 ± 13.96, 178.6 ± 13.94 mmol/l thrombin × min). Cmax and ETP reached a maximum in the presence of 70 ng/ml dabigatran.

Fig. 1.

Effect of dabigatran on thrombin generation. The effect of various range of dabigatran (0–566 ng/ml) on thrombin generation in normal, protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma. Low concentrations of dabigatran (70 ng/ml) paradoxically enhanced the expression of thrombin generation (a). The phenomenon did not exist in protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma (b and c). Levels of Cmax and ETP initially increased at low concentrations of dabigatran and decreased at higher concentrations of dabigatran (d and e). ∗P < 0.05 vs. respective controls. ETP, endogenous thrombin potential.

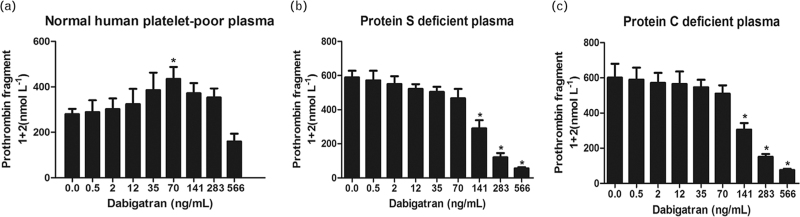

Effect of dabigatran on F1+2 assay

F1+2 assay is another method to assess thrombin generation. F1+2 assay showed results similar to CAT assay (n = 6) (Fig. 2). In normal plasma, 70 ng/ml dabigatran paradoxically significantly increased F1+2 from 289.4 ± 136.9 to 435.3 ± 115.8 nmol/l. Moreover, there was an enhancement in thrombin generation, which decreased at higher concentrations of dabigatran. In protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma, the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation was absent. Higher concentrations of dabigatran significantly suppressed the generation of F1+2. F1+2 decreased from 589.3 ± 101.6 to 290.5 ± 127.2 nmol/l or from 600.7 ± 209.4 to 305.6 ± 98.1 nmol/l in protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma in the presence of 141 ng/ml dabigatran.

Fig. 2.

Effect of dabigatran on prothrombin fragments 1+2 (F1+2) assay. Low concentrations of dabigatran dose-dependent increased F1+2 in normal plasma (a). In protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma, the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation was absent. F1+2 decreased in a dose-dependent manner as the concentrations of dabigatran increased (b and c). ∗P < 0.05 vs. respective controls.

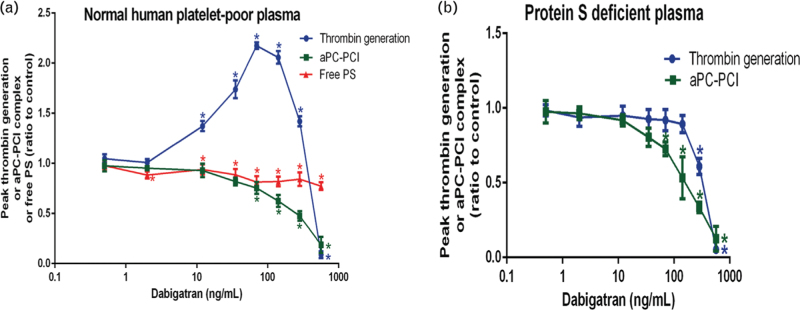

Effect of dabigatran on activated protein C levels

We evaluated APC levels by ELISA kit. The formation of APC was dose-dependently decreased by dabigatran in normal as well as protein S-deficient plasma. In both plasmas, APC level was significantly suppressed at 70 ng/ml. We also evaluated free protein S levels. Free protein S was completely absent in protein S-deficient plasma, whereas normal levels were measured in our normal plasma. We observed a minor as yet unexplained reduction of free protein S in normal plasma upon addition of dabigatran (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of dabigatran on activated protein C levels. In normal plasma, thrombin generation increased but free protein S and activated protein C decreased (a). In protein S-deficient plasma, we showed that thrombin generation and APC gradually decreased as the concentrations of dabigatran increased (b). ∗P < 0.05 vs. respective controls. APC, activated protein C.

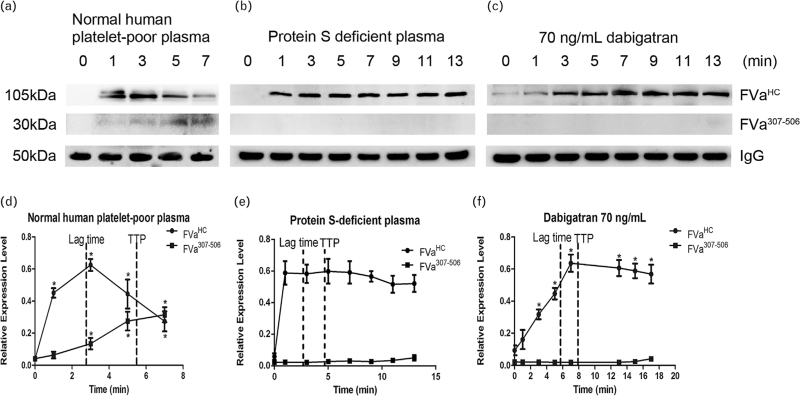

Effect of dabigatran on the generation and degradation of factor Va

FVaHC and FVa307–506 are indices of FVa generation and inactivation, respectively. In normal plasma, FVaHC increased with time, peaking around the lag time in the CAT assay and then decreased. In contrast, FVa307–506 increased gradually with time (Fig. 4a and d). Interestingly, FVa307–506 formation was not observed in protein S-deficient plasma (Fig. 4b and e) and in plasma spiked with low-dose dabigatran (Fig. 4c and f). Under these conditions, levels of FVaHC remained high for an extended period of time. In normal plasma that was spiked with 70 ng/ml dabigatran, the prolonged lag time and TTP in CAT coincided with delayed FVa degradation. These results indicate that delayed FVa degradation contributes to the increase in thrombin generation not only in protein S-deficient plasma but also in normal plasma spiked with low-dose dabigatran.

Fig. 4.

Effect of dabigatran on factor Va generation and degradation. (a) The expression of FVaHC and FVa307–506 levels after activation of coagulation cascade in normal plasma. (d) Cleaved FVa increased after activation of coagulation cascade. In protein S-deficient plasma, degradation of FVa and generation of FVa307–506 were inhibited (b and e). In normal plasma spiking with 70 ng/ml dabigatran, generation of FVa was delayed and degradation of FVa inhibited. (c and f) ∗P < 0.05 vs. respective controls.

Discussion

This study showed that protein S participated in the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation in plasma spiking with low concentrations of dabigatran. Dabigatran increased thrombin generation by inhibiting FVa degradation. Previous study demonstrated that low concentrations of dabigatran paradoxically increased thrombin generation in protein C-dependent manner [8]. Dabigatran inhibited thrombomodulin-bound thrombin more aggressively than thrombin at low concentrations resulting in the decrease of protein C activation and FVa degradation. Our previous study speculated that higher concentrations of dabigatran may sufficiently suppress thrombin and coagulation cascade [17]. As a cofactor to APC, protein S could assist APC to cleave FVa and FVIIIa [11]. However the effect of protein S on the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation has not been well addressed.

It is known that a transient hypercoagulable state occurs within the first 12–60 h of warfarin treatment because of inhibition of protein C and protein S [18]. Previous study showed that low concentrations of dabigatran paradoxically increased thrombin generation. We aimed to disclosure whether the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation induced by low concentrations of dabigatran depends on protein S. Protein S is a vitamin K-dependent glycoprotein that plays vital role in blood coagulation. Protein S circulates in plasma at a concentration of around 350 nmol/l which exists both in a free form (≈140 nmol/l) and in an inactive form (∼60%) combined with the complement regulatory factor C4b-binding protein (C4BP) [13]. Free protein S exerts co-factor activity [19].

Firstly, thrombin generation was assessed by CAT assay in normal, protein S-deficient or protein C-deficient plasma containing 10 nmol/l rhs-TM. It has been previously shown that 10 nmol/l rhs-TM added to the plasma was appropriate to mimic the condition in vivo[20]. Thrombin–thrombomodulin is usually not present during CAT assays but was required in the present study to be able to assess the APC/protein S anticoagulant pathway. Blood coagulation cascade includes two pathways, one of which is contact factor-dependent intrinsic pathway and the other is tissue factor (TF)-induced extrinsic pathway. In most cases, thrombin generation was assessed in coagulation reaction induced by extrinsic pathway. In our study, final concentration of tissue factor, phospholipids, fluorogenic substrate, and CaCl2 were 5 pmol/l, 4 μmol/l, 417 μmol/l, and 16.7 mmol/l. Under these circumstances, coagulation cascade process could be induced completely. Wagenvoord et al.[21] reported that the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation induced by low concentrations of dabigatran may be caused by the presence of α2-macroglobulin–thrombin (α2MT) complex. CAT assay uses an algorithm to subtract α2MT activity from the total amidolytic activity. The transient enhancement of α2MT induced by dabigatran could not be subtracted, which leads to a false increase of thrombin generation. Both the α2MT and the thrombin–thrombomodulin effect may contribute to the paradoxical thrombin generation increase in CAT by low dabigatran. However, there is study showing different opinion which reported α2M may not participate in the enhancement of thrombin generation [22]. CAT assay showed that low concentrations of dabigatran paradoxically induced thrombin generation in normal plasma. Absence of this paradoxical increase in CAT with protein S as well as protein C-deficient plasma point towards a role of dabigatran in the protein S/protein C system rather than in the protein S/TFPI system. Higher concentrations of dabigatran may sufficiently suppress thrombin and coagulation cascade.

Secondly, thrombin generation was assessed by F1+2 assay under the same circumstance. F1+2 is also a marker of thrombin generation. Our results showed that F1+2 increased in normal plasma spiking with 70 ng/ml dabigatran. The paradoxical enhancement of F1+2 was absent in protein S-deficient plasma. The results are inconsistent between assays. However, the trend of CAT and F1+2 assays is same. Previous study showed that thrombin generation increased at 136–545 ng/ml dabigatran. But only 273 ng/ml dabigatran increased F1+2[23]. Our results are similar to other study.

The activity of coagulation and anticoagulation factors using clot methods may be adversely affected by dabigatran [24]. Dabigatran dose-dependent decreased factor V and factor VIII activity and increased protein S and protein C activity. Then, APC-PCI ELISA were used. In normal plasma, the concentrations of dabigatran for inhibition protein C activation were almost the same as for enhancement of thrombin generation. Except for protein C, protein S participates in the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation in plasma spiking with low concentrations of dabigatran.

Last but not least, we used western blot assay to evaluate the generation and degradation of FVa. In normal plasma, FVa307–506 increased in line with the decrease of FVaHC. In protein S-deficient plasma, the degradation of FVa was absolutely suppressed. Protein S plays an important role in the degradation of FVa. In normal plasma spiking with 70 ng/ml dabigatran, the generation of FVa was not affected. However, the degradation of FVa was inhibited. We speculated low concentrations of dabigatran suppressed protein S and APC more than coagulation cascade leading the paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation.

Conclusion

This study still has some limitations. In one hand, most parts of our results are based on CAT assay. It has been reported α2MT would affect the results. What is more, there may be some confounding factors that affect the results. In the other hand, this study was performed in vitro. Although the concentrations of dabigatran used in vitro are close to the condition in vivo, the results may not reflect the actual situation in vivo. It would be more interesting to perform the experiments in patients.

Acknowledgements

Funding: this work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (BXQN202210), ‘Gusu Wei Sheng Ren Cai’ program (2021048), and Gusu Talent Program (GSWS2021002). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval: this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

C.Z., W.C., and Y.Z. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Tsai C-T, Liao J-N, Chen S-J, Jiang Y-R, Chen T-J, Chao T-F. Nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in AF patients >/= 85 years. Eur J Clin Invest 2021; 51:e13488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Xu Y, Li L, Lu W. Thrombin aggravates hypoxia/reoxygenation injury of ardiomyocytes by activating an autophagy pathway-mediated by SIRT1. Med Sci Monit 2021; 27:e928480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spence JD. Cardioembolic stroke: everything has changed. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2018; 3:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempfle C-E. Direct oral anticoagulants--pharmacology, drug interactions, and side effects. Semin Hematol 2014; 51:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furugohri T, Fukuda T, Tsuji N, Kita A, Morishima Y, Shibano T. Melagatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, but not edoxaban, a direct factor Xa inhibitor, nor heparin aggravates tissue factor-induced hypercoagulation in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2012; 686:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furugohri T, Morishima Y. Paradoxical enhancement of the intrinsic pathway-induced thrombin generation in human plasma by melagatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, but not edoxaban, a direct factor Xa inhibitor, or heparin. Thromb Res 2015; 136:658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furugohri T, Shiozaki Y, Muramatsu S, Honda Y, Matsumoto C, Isobe K, Sugiyama N. Different antithrombotic properties of factor Xa inhibitor and thrombin inhibitor in rat thrombosis models. Eur J Pharmacol 2005; 514:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamisato C, Furugohri T, Morishima Y. A direct thrombin inhibitor suppresses protein C activation and factor Va degradation in human plasma: possible mechanisms of paradoxical enhancement of thrombin generation. Thromb Res 2016; 141:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esmon Charles T. Molecular events that control the protein C anticoagulant pathway. Thromb Haemost 1993; 70:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenflo Johan. Structure-function relationships of epidermal growth factor modules in vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. Blood 1991; 78:1637–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlback B. Pro- and anticoagulant properties of factor V in pathogenesis of thrombosis and bleeding disorders. Int J Lab Hematol 2016; 38: (Suppl 1): 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolaes Gerry AF, Dahlback B. Factor V and thrombotic disease: description of a janus-faced protein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002; 22:530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlback B. Vitamin K-dependent protein S: beyond the protein C pathway. Semin Thromb Hemost 2018; 44:176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gierula M, Ahnstrom J. Anticoagulant protein S-new insights on interactions and functions. J Thromb Haemost 2020; 18:2801–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeb MJ, Marzec U, Gruber A, Hanson Stephen R. Antithrombotic activity of protein S infused without activated protein C in a baboon thrombosis model. Thromb Haemost 2012; 107:690–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furugohri T, Sugiyama N, Morishima Y, Shibano T. Antithrombin-independent thrombin inhibitors, but not direct factor Xa inhibitors, enhance thrombin generation in plasma through inhibition of thrombin-thrombomodulin-protein C system. Thromb Haemost 2011; 106:1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C, Zhang P, Li H, Han L, Zhang L, Yang X. The effect of dabigatran on thrombin generation and coagulation assays in rabbit and human plasma. Thromb Res 2018; 165:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stirling Y. Warfarin-induced changes in procoagulant and anticoagulant proteins. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1995; 6:361–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodhams Barry J. The simultaneous measurement of total and free protein S by ELISA. Thromb Res 1988; 50:213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esmon Charles T. The protein C pathway. Chest 2003; 124: (3 Suppl): 26S–32S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagenvoord RJ, Deinum J, Elg M, Hemker HC. The paradoxical stimulation by a reversible thrombin inhibitor of thrombin generation in plasma measured with thrombinography is caused by alpha-macroglobulin-thrombin. J Thromb Haemost 2010; 8:1281–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagenvoord RJ, Hemker HC. The action mechanism of direct thrombin inhibitors during coagulation. J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9: (Suppl S2): 573. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perzborn E, Heitmeier S, Buetehorn U, Laux V. Direct thrombin inhibitors, but not the direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban, increase tissue factor-induced hypercoagulability in vitro and in vivo. J Thromb Haemost 2014; 12:1054–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Favaloro EJ, Lippi G. Interference of direct oral anticoagulants in haemostasis assays: high potential for diagnostic false positives and false negatives. Blood Transfus 2017; 15:491–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]