Abstract

Acrylamide (ACR) with its extensive industrial applications is a classified occupational hazard toxin and carcinogenic compound. Its formation in fried potatoes, red meat and coffee during high-temperature cooking is a cause for consideration. The fabrication of chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles (CSP NPs) aims to enhance the bioavailability of probiotics in the gut, thereby improving their efficacy against ACR-induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Nanoencapsulation, a vital domain of the medical nanotechnology field plays a key role in targeted drug delivery, bioavailability, multi-drug load delivery systems and synergistic treatment options. Our study exploited the nanoencapsulation technology to coat Lactobacillus fermentum (probiotic) with chitosan (prebiotic), both with substantial immunomodulatory effects, to ensure the stability and sustained release of microbial load and its secondary metabolites in the gut. The combination of pre-and probiotic components, called synbiotic formulations establishes the correlation between the gut microbiota and the overall well-being of an organism. Our study aimed to develop a potent synbiotic to alleviate the impacts of heat-processed dietary toxins that significantly influence behaviour, development, and survival. Our synbiotic co-treatment with ACR in fruit flies normalised neuro-behavioural, survival, redox status, and restored ovarian mitochondrial activity, contrasting with several physiological deficits observed in the ACR-treated model.

Keywords: Gut microbiota, Nanoencapsulation, Acrylamide, Bioactives, Chitosan, Lactobacillus

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Biotechnology, Developmental biology, Microbiology, Environmental sciences, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Gut health has gained considerable attention recently and has become an essential part of most fitness regimes. The gut microbiota, consisting of trillions of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract, plays a crucial role in maintaining human health and well-being. This microbial community is not just a passive bystander but actively contributes to numerous physiological processes essential for human health including mental fitness, immunological and metabolic mechanisms. However, this niche of vital microbes gets easily disrupted due to several factors including the consumption of foods lacking fibre content, lack of exercise, stress, excessive intake of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), etc. Among these factors affecting the gut microbiome, the food we consume plays a major role in regulating our health1.

The healthy food items or supplements we consume undergo several physical and chemical changes during digestion in our gastrointestinal tract before the nutrients from them get absorbed into our body. These nutrients or bioactives present in our vegetables, herbs, spices, or fruits serve as cofactors, vitamins, or essential factors for better functioning of our body. However, their absorption in the small intestine is often affected by several factors including chemical form, matrix, and metabolic pathways2. Therefore, it is essential to develop a suitable delivery matrix to ensure the bioavailability of essential bioactives for a healthy population. Advances in nanotechnology offer us vast opportunities to manipulate the chemical, physical and biological properties of various compounds to suit our goals. One such development is the synthesis of nano-delivery systems made with biocompatible materials that ensure slow-release mechanisms for enhanced bioavailability3.

Probiotics are microbes that improve health by modulating the gut microbiota. Some probiotic species, such as Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia, interact with the gut microbiota, increasing beneficial bacteria and reducing pathogenic species. This interaction can help restore the gut microbiota from dysbiosis. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium pseudolongum can help recover gut microbiota dysbiosis in obese mice, increasing the abundance of Butyricimonas and Bifidobacterium4. Probiosis is a process where bacteria, such as Lactobacillus strains, can alter the composition and function of the intestinal microbiome. These bacteria produce antimicrobial agents or metabolic compounds that suppress the growth of other microorganisms or compete for receptors and binding sites with other intestinal microbes. They can also enhance the integrity of the intestinal barrier, resulting in immune tolerance and decreased translocation of bacteria across the mucosa5.

Probiotics can also modulate intestinal immunity and alter the responsiveness of intestinal epithelia and immune cells to microbes in the intestinal lumen. Studies have shown that probiotic treatment can reduce pain and flatulence in patients with IBS, but not many have demonstrated associations with altered microbiota6,7. Probiotic supplements have been shown in studies to boost gut microbiota quantity, but they cannot alter microbial metabolites on their own accord. Synbiotics, a mix of probiotics and prebiotics, have been created to enhance the gut microbiota by modifying certain species, whereas prebiotics feed the microbiota and impact metabolite formation, notably short-chain fatty acids (SCFA)8,9.

Our study fabricated chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles (CSP NPs) to ensure the bioavailability of the probiotic load (L. fermentum) in the gut with a sustained release profile. The chitosan coating doubles as a prebiotic (non-digestible fibre that enhances the functionality of probiotics in the gut) and as a delivery system with innate immunomodulatory and antioxidant effects. Consequently, we analysed the efficiency of this synthesised synbiotic formulation against common heat-processed toxins—acrylamide (ACR) using the Drosophila melanogaster model.

ACR is a white crystalline compound used in textiles, paper, cosmetics, cement, and mining processes. It has been classified as hazardous and probable carcinogenic to humans due to its presence in industrial effluents. In humans, ACR has been observed to cause muscle weakness, impaired cognition, and peripheral neuropathy in employees exposed via inhalation or skin absorption10,11. Several food and drug associations have set standards and mitigation strategies to reduce ACR formation or presence in food products. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) set 4–5 μg/kg bw/day acrylamide from food as the highest tolerable intake level in 200512,13. In India, the major source of acrylamide is the consumption of deep-fried food products ranging from 82.0 to 4245.6 µg/kg14. Exposure studies by the US CDC organization in 2019 showed that children aged 3–11 had 108–93.8 pmol/g haemoglobin, while older adults had 223–257 pmol/g haemoglobin15.

The post-pandemic state has aggravated the situation, with young children being twice as impacted as adults due to their eating habits, rapid metabolism, and low body weight. Fast food intake has also grown, which may raise the risk of infertility16,17. ACR’s negative effects have been explored in model organisms such as rats, mice, zebrafish, and Drosophila, with findings indicating circadian clock disturbance, developmental delays, and neurotoxic effects18–24. Drosophila melanogaster is used as a model organism to study and understand various diseases, their molecular mechanisms, and their effects on humans. It is a widely preferred model due to its short life cycle, genetic similarity to humans, and high fecundity rate. Additionally, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have been reported to have nutrient-dependent regulatory control on Drosophila development and can regulate growth hormones like ecdysone and insulin receptors25. Storelli et al. also reported the influence of LAB on the developmental mechanisms in Drosophila under nutrient-scarce conditions26. Furthermore, studies with Lactobacillus strains have reported that these bacteria can alleviate the ACR-induced oxidative stress in vivo models and reduce the bioavailability of dietary acrylamide under different simulated gastrointestinal conditions (in vitro)22,27.

Therefore, in this study, we have discussed the formulation process of chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles, Further, our study analyses the efficiency of these synbiotic formulations against ACR-induced toxicity using the fruit fly model. Our results demonstrate the extended bioactivity of the probiotic load as well as its protective mechanisms against ACR-induced toxicity.

Results

Characterisation of CSP NPs

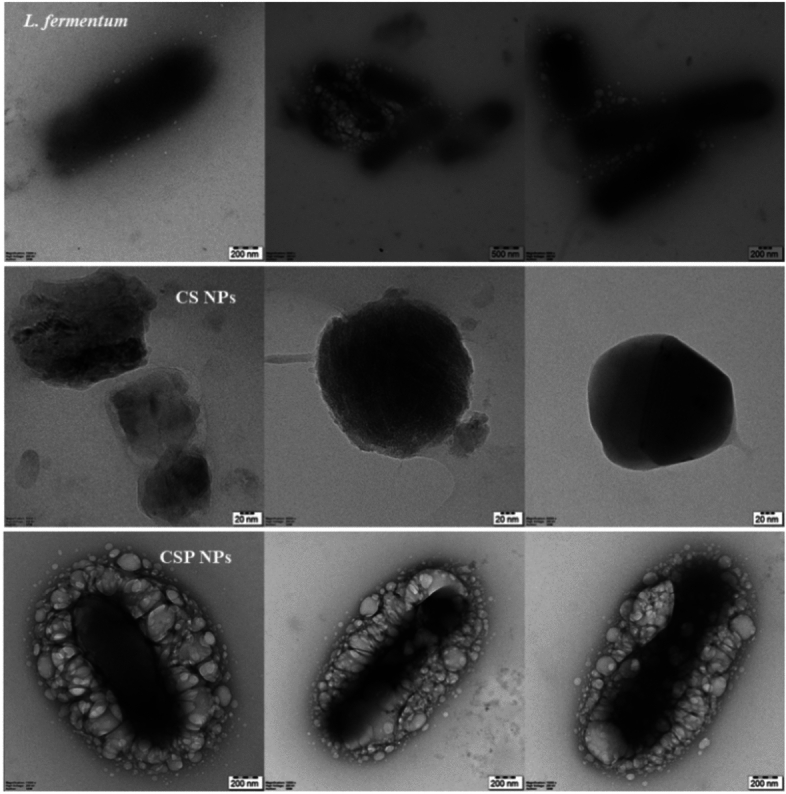

Chitosan and chitosan encapsulated probiotic nanoparticles were analysed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM). The synthesised CS NPs without the probiotic load were small and spherical with an average size of 110 nm. The nanoencapsulation process of L. fermentum within chitosan NPs showed a significant increase in size (565 nm) and elongated morphology. The increase in size and morphological changes indicate the successful encapsulation of probiotics within the chitosan matrix. Figure 1 (CSP NPs) shows a rod-shaped bacterial cell tightly surrounded by small spherical chitosan particles that may act as a barrier to protect the probiotic load in acidic conditions. Furthermore, the TEM image of L. fermentum before encapsulation was observed to be 1000–1060 nm, to ensure effective nanoencapsulation the bacterial cells are sonicated to reduce the size and prevent aggregates. The fact that the encapsulated nanoparticles are 565 nm, significantly larger than the 110 nm CS NPs but smaller than the original 1060 nm probiotic cells, suggests that the encapsulation and lyophilization process may compress or compact the probiotic cells to some extent.

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy. Probiotic, chitosan, and chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles were imaged using the TEM technique.

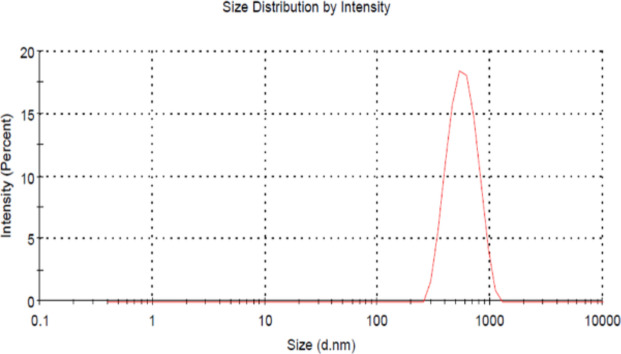

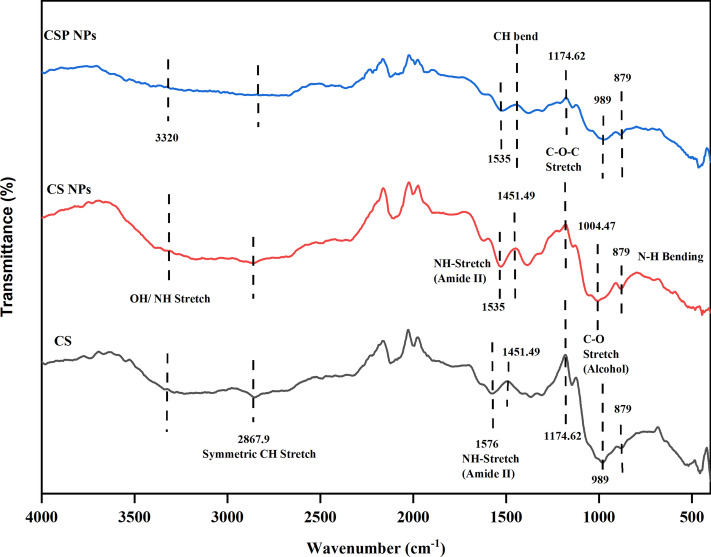

Figure 2 illustrates the particle size and charge of the synthesised CSP NPs. The average zeta potential of the coated probiotic NPs was 4.38 ± 15.8 mV with a Z-average of 663.4 d. nm and a polydispersity index of 0.427 ± 0.87. Overall, high absolute zeta potential, nanoscale hydrodynamic diameter, and narrow size distribution range ensure the stability of the particles in suspensions. FTIR analysis detects the presence of functional bonds and peak shifts occur when interacting with other compounds. Chitosan comprises primarily O–H and N–H stretching, C–H stretching, amide bands, and C–O–C stretching among other peaks. The presence of these functional groups is characterised by 3320, 1451, 1576, and 989 cm−1 respectively28. Figure 3 illustrates the slight shift in the amide bonds characterised by peaks at 1535 cm−1 in CS and CSP NPs and can be related to the interaction between chitosan and TPP29. Similarly, the peak corresponding to the C–O stretch indicated a shift from 989 to 1004.47 cm−1 in CS NPs but was retained in CSP NPs. This can be explained by the glycosidic bonds present in polysaccharides, present in chitosan as well as the bacterial cell wall of Lactobacillus fermentum. With chitosan (CS) as a reference peak, we can confirm the presence of chitosan in the synthesised NPs and mild shifts in existing peaks could be linked to interactions between the bacterial components.

Fig. 2.

Zeta size distribution analysis. The size and particle charge of chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles were analysed using the zeta potential technique.

Fig. 3.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The presence of functional groups in standard chitosan and synthesised NPs (CS and CSP) were analysed to ensure purity.

Viability of synthesised CSP NPs

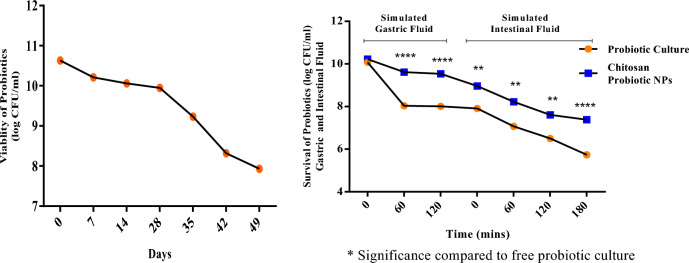

CSP NPs bacterial load viability was determined using the pour plate method as illustrated in Fig. 4. The synthesised nanoparticles indicated an average viability of 7.93 log CFU/ml for 49 days. Furthermore, the viability and release profile of the synthesised CSP NPs under simulated gastrointestinal fluid systems demonstrated subsequent stability of the probiotic load (SGF120 = 9.07 log CFU/ml; SIF180 = 7 log CFU/ml) compared to the free probiotic culture with SGF120 = 8 log CFU/ml and SIF180 = 5.87 log CFU/ml.

Fig. 4.

Viability of CSP NPs. The viability of chitosan-coated L. fermentum cells was analysed periodically to determine the efficacy of the synthesised CSP NPs. Simulated gastrointestinal systems were utilised to determine the survival and release profile of the fabricated CSP NPs.

Effect of CSP NPs on survival and behavioural parameters in ACR-treated flies

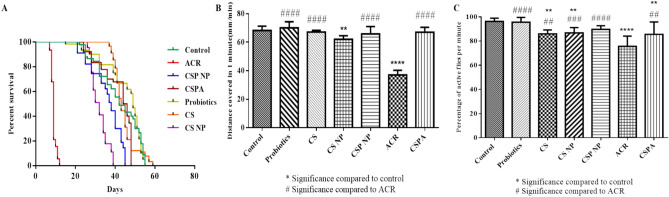

The synthesised CSP NPs were orally administered to the fruit fly model to assess their efficiency against common environmental and food-borne toxins like acrylamide (ACR). ACR-treated flies demonstrated low survival capacity (12 days), reduced larval crawling (37 mm/min) and declined climbing activity in adult male flies (75.55%) as illustrated in Fig. 5A–C respectively. Alternatively, the control (55 days; 68.25 mm/min; 96.29%) and co-treated flies (CSPA = 48 days; 67.03 mm/min; 85.55%) demonstrated a significant level of activity and survival capacity. Baseline control groups like CS (59 days; 67.1 mm/min; 85.92%), CS NPs (39 days; 62.03 mm/min; 86.7%) and probiotics (55 days; 70.07 mm/min; 95.55%) treatments were also assessed for their effect on fly survival and behaviour parameters. These controls did not indicate any negative impact on Drosophila lifespan and locomotor functions as evidenced by the data.

Fig. 5.

Survival and Behavioural Parameters of D.mel. The effects of CSP NP were tested against ACR-induced survival (A) and behavioural deficits (B, C) using the fruit fly model.

CSP NP modulates ACR-induced redox stress factors in D.mel

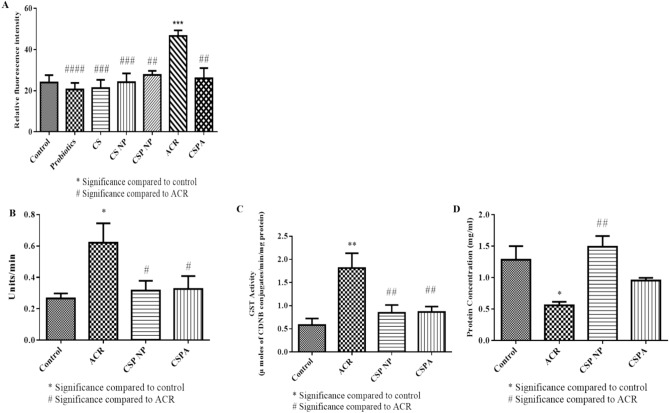

Male flies post-exposure to respective treatment groups were homogenised in suitable buffers to estimate redox stress parameters. Following the behaviour analysis, baseline control groups (CS, CS NPs and probiotics) along with control, ACR and CSPA groups were tested for fluctuations in the ROS levels. As illustrated in Fig. 6A, there were no significant variations in ROS levels between the control and baseline control groups. The observed ROS levels are commonly attributed to normal cellular activity, however, a marked increase in ROS intensity was noticed in flies treated with ACR thereby indicating the presence of xenobiotic-induced oxidative stress and activation of antioxidant mechanisms. Owing to the non-toxic nature of the baseline control groups (CS, CS NPs and probiotics) as evidenced by long survival period, high locomotor function at larval and fly stages and no significant induction of ROS levels, further experiments were performed with control, ACR, CSP NPs and CSPA treatment groups.

Fig. 6.

Biochemical Factors of D.mel. The effects of CSP NP were tested against ACR-induced ROS levels (A), antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD—B and GST—C) and protein levels (D) using the fruit fly model.

ACR-treated flies exhibited increased ROS, SOD and GST activities as depicted in Fig. 6A–C respectively. Furthermore, ACR exposure indicated a negative influence on protein levels (Fig. 6D). On the other hand, the CSPA-treated group demonstrated a significant recovery in ROS and antioxidant enzyme activity levels. Comparing the data with the control group revealed the prominent effect of CSPA treatment in restoring the alterations in vital biochemical factors and thereby curbing the toxic influence of ACR within the fruit fly model.

CSP NPs reverse ACR-induced mitochondrial membrane depolarisation in D.mel ovaries

Ovaries dissected from treated female flies were stained with TMRE solution to estimate the influence of ACR and CSPA treatment on mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) as illustrated in Fig. 7. TMRE dye accumulation in control and CSPA was observed indicating the presence of an active mitochondrial population. Whereas, the ACR-treated samples were noted to have a substantial reduction in TMRE fluorescence indicating the role of ACR to induce mitochondrial depolarisation. This result indicates the functionality of CSPA treatment in protecting against ACR-induced mitochondrial depolarisation and subsequent apoptosis mechanisms at the cellular level.

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in D.mel ovaries. TMRE staining of fruit fly ovaries showing changes in mitochondrial membrane potential post-treatment. Increased fluorescence intensity was observed in control and CSPA groups than in ACR-treated flies.

Discussion

Heat-processed contaminants (HPC) are compounds formed during the thermal processing of food items, such as frying, baking, and grilling, to enhance texture and flavour. These compounds, such as acrylamide, furans, bisphenol-A, and chloropropanols, are found in various baked and fried food products. While health and safety organizations have established strict regulations on HPC concentrations in industry-manufactured food products, HPCs are hidden dangers that we are exposed to through our daily dietary intake30. ACR, formed through the Maillard reaction, is more prominent in fried potatoes, roasted coffee, fried red meat, and baked confectionaries. ACR has been widely studied and several therapeutic formulations aiming to curb the redox stress to control ACR-induced toxic effects have been reported using varied animal models19,20,31–34. However, it is important to understand the involvement of the gut when analysing food-based toxicological studies. Animal studies have reported ACR-induced cognitive impairments via the gut-brain axis, intestinal barrier damage, gut microbial dysbiosis, bile acid metabolism challenges, and higher cholic acid levels35–37. Additionally, ACR was observed to cause changes in intestinal morphology, disrupt the enteric nervous system, increase apoptotic markers in the GI tract, aggravate mucosal inflammation and damage tight junctions36,38–40. Therefore, it is crucial to formulate dietary supplements that can reduce, restore, or protect our physiological systems from these food-processed toxins.

In the extensive field of food-based research, our chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles emphasise the benefits of using simple, naturally accessible dietary supplements to mitigate the detrimental effects of dietary contaminants. The notion of 'gut-brain interaction' has recently gained popularity. Many people have recognised the importance of the gastrointestinal system, sometimes known as the second brain of the human body, and its impact on general well-being. The gut microbiota is an important regulator of the enteric system and contributes to gut-brain crosstalk, which influences mental, metabolic, and immunological health4. This study uses chitosan, a natural biopolymer, to create sustained-release probiotic supplements. Probiotics like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are easily sourced from milk, curd, and fermented products. Studies show recovery of gut dysbiosis, colonic inflammation, and improved microbiota diversity. Combining probiotic supplements with prebiotics like inulin, chitosan, and arabinoxylan can significantly modulate gut microbiota, enhancing the accumulation of beneficial gut microbiota and reducing harmful colonic bacteria4.

Lactobacillus fermentum is a probiotic strain that can enhance gut health by strengthening the intestinal barrier, amplifying the gut response, reducing inflammation, and modulating the immune system. It increased mucus production, stimulated the release of anti-microbial peptides, and produced secretory immunoglobulin A. It was also reported to maintain the gut epithelium barrier and colon tissue integrity41,42. L. fermentum can also reduce inflammation-associated tumorigenesis and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It also supports the immune system by increasing epithelial barrier integrity. Additionally, L. fermentum can improve gut microbiota composition, reduce blood cholesterol, and increase antioxidant enzyme activity43–46. Chitosan is a non-plant-derived prebiotic that can enhance gut flora, boost probiotic activity, and inhibit pathogens. Chitosan has been permitted as food additives and active ingredients in several countries, including the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, and China. They are also classified as Generally Recognised as Safe (GRAS) by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Researchers claim that chitosan and its derivatives can improve animal gastrointestinal health, growth performance, productivity, nutrient absorption, and immunity47.

We fabricated CSP NPs by coating the Lactobacillus fermentum culture with low molecular weight chitosan in the presence of TPP. Gunasangakaran et al. 2022 reported the synthesis and characterisation of chitosan-probiotic nanoparticles with chitosan and TPP concentrations as 0.05 mg/ml and 0.1 mg/ml respectively. The developed synbiotic product showed a high surface charge and polydispersity index with a size range of 360–500 nm via SEM imaging48. Ebrahimnejad et al.49 prepared synbiotic NPs with chitosan concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 0.5 mg/ml with 0.1 mg/ml TPP to assess the difference in the nano-formulation size and bacterial load capacity. The study reported that with the increase in chitosan concentration, the bacterial encapsulation greatly decreased. The highest encapsulation load was reported in nano-formulation synthesized with 0.05 mg/ml chitosan49. Another study by Alkushi et al.50 reported the preparation of NPs with 0.4% chitosan and 20 g/L alginate as an effective therapeutic formulation against colon inflammation with a size range of 21–25 nm50. Multiple other synbiotic nano-formulations have been synthesised and characterised to demonstrate effective delivery of the probiotic load51,52. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no other studies have reported the effectiveness of synbiotic nano-formulations against HPCs.

Based on data reported by Ebrahimnejad et al.49, the present study utilized 0.5% chitosan and 1 mg/ml TPP to synthesise the synbiotic nano-formulation, CSP NPs. Our TEM images of free probiotic culture, CS NPs and CSP NPs indicated the effect of nanoencapsulation wherein the 1µm size of free probiotics and 110 nm CS NPs transformed to 400–500 nm CSP NPs. Although the NPs size reported by existing studies is relatively smaller than the present formulation, it is important to note that our CSP NPs hold thrice the amount of probiotic load (3 ml; 8 log CFU/ml) comparatively49,50,53. Zeta potential reflects the surface charge of the nanoparticles, which is a critical factor in determining their stability in suspension. A zeta potential of 4.38 mV suggests that the nanoparticles have a moderate positive surface charge. This level of zeta potential indicates that the nanoparticles may have significant stability in suspension, with a low risk of aggregation over time54.

Additionally, PDI measures the distribution of particle sizes within a sample, with values ranging from 0 to 1. A PDI of 0.427 suggests that the particle size distribution is low polydispersity. This means that while the particles are not all the same size, there is not an extreme variation in size which conforms to moderate stability and low aggregation rates in suspensions55. Additionally, the nanoscale ensures potential permeability across the physiological barriers as the intestinal endothelial cells have a 1.2–2 µm intercellular distance56. Furthermore, FTIR data of CSP NPs illustrated the presence of chitosan characteristic peaks namely, O–H and N–H stretching, C–H stretching, amide bands, and C–O–C stretching. Slight shifts or changes in intensity compared to the spectrum of pure chitosan observed might occur due to the nanoparticle formulation process, interactions, or modifications. These characteristic peaks confirm the presence and structure of chitosan within the nanoparticles29. Our in vitro experiments also demonstrated the stability and viability of CSP NPs through repeated storage viability analysis at room temperature and under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. The storage viability demonstrated substantial probiotic viability after 49 days indicating a higher shelf life of CSP NPs when stored as lyophilised powder. Additionally, the main aspect of the encapsulation process is to offer considerable protection for the probiotic load for 6 h (digestion in stomach = 2 h; in intestine = 4 h) against acidic pH in the stomach and bile salts in the intestine. Subsequently, our simulated GI studies demonstrated significant viable probiotic load post-6-h thereby demonstrating the efficiency of chitosan nano-coating on the probiotic load and slow-release profile57.

Our experimental data in the fruit fly model demonstrated the efficiency of CSP NPs against ACR by enhancing behavioural functions at larval and adult fly stages. The treated flies exhibited increased survival capacity, normalised ROS levels, and no fluctuations in antioxidant enzyme activities. Furthermore, the MMP in CSPA-treated ovaries demonstrated substantial TMRE intensity indicating the presence of an active mitochondrial population. The in vivo study confirms the interplay between synbiotic supplements and ACR toxicity mitigation strategy. Baseline groups such as probiotics, CS and CS NPs treatments were also analysed to rule out their influence on the fruit fly model. Behavioural and ROS levels indicated no noteworthy influence of the baseline groups on the fly physiology as evidenced by no significant variance compared to the control group.

The lifespan and behavioural parameters in the fruit fly model are vital life-history traits and are generally very closely associated with the interaction between environmental cues and neuromuscular coordination. While ACR treatment shortened the lifespan and reduced larval crawling and adult climbing behaviour, the CSPA treatment did not exhibit any alterations compared to the control group. The influence of synbiotics in suppressing the impact of ACR can be observed. However, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the present study serves as the first to analyse the effects of synbiotic formulation against ACR in the D.mel model. We can corroborate the present results with Gómez et al.58 who reported the impact of commensal microbiota on the behaviour of the fruit fly model. The study explored the effects of axenic (no gut microbiota) and probiotic-treated fly models and described the positive influence of probiotic treatment on fly development and behaviour58.

Furthermore, ACR treatment groups exhibited increased ROS and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD and GST) while these levels were on par with control groups in the flies exposed to CSPA treatment groups. While ROS production is essential for cellular functioning, homeostasis sets in motion a positive feedback loop that effectively maintains a balance between redox stress levels and antioxidant mechanisms for healthy physiology. However, xenobiotic exposure disrupts this balance causing an increase in stress markers and subsequent activation of the antioxidant mechanisms. The normalised levels of ROS, SOD and GST in CSPA treatment imply a balance between the redox factors, once again demonstrating the protective influence of synbiotics at the cellular level. A similar study by Westfall et al.59, demonstrated the influence of synbiotics in normalising the redox stress factors in aged flies and correlated the data with cognitive impairments observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

Finally, ovarian mitochondrial depolarisation can also be linked to our earlier findings reporting low survival rate and high redox stress. Unfavourable conditions and ACR’s direct influence on MMP trigger the apoptotic pathways leading to non-functional ovaries and teratogenic attributes of ACR. However, CSPA-treated ovaries exhibited highly active mitochondrial pools. We believe in addition to the synbiotic formulation, the probiotic strain used in this study—L. fermentum and its metabolite ferulic acid play a vital role in protecting the fly model against ACR-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent developmental toxicity. As reported by Westfall et al.60, the probiotic strain and its metabolite greatly influence dTOR and IlS signalling pathways. These pathways mainly target nutrient-mediated development processes, furthermore correlating this mechanism in humans implies its effect on hormonal regulations, puberty-related changes, obesity, diabetes and in some instances neurodegenerative disorders60.

Overall, the CSPA (CSP NPs + ACR) treatment demonstrated no significant toxicity at adult and larval stages within the fruit fly model. Therefore, we postulate that the cotreatment of synbiotics with ACR enhances the gut barrier by modulating the composition and activity of the gut microbiota. Chitosan NPs coating serving as a protective matrix ensures the delivery and controlled release of the probiotic load in the gut and aids in intestinal mucosal adhesion. Additionally, the L. fermentum load in interaction with CS NPs can produce SCFAs and antimicrobial peptides. This interaction can potentially stimulate gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), enhance mucosal immunity, regulate inflammatory responses, and promote tolerance to harmless antigens, thereby reducing inflammation and improving intestinal barrier function60–63. Therefore, we postulate that by maintaining gut integrity and reducing intestinal permeability, they prevent systemic inflammation and the translocation of toxins (like ACR metabolites—glycidamide) into circulation.

With positive outcomes of CSP NPs in the fruit fly model, it is imperative to comprehend the differences in the commercially available probiotic and synbiotic formulations. The strain origin and CFU count are information generally withheld as a part of trade secrets, therefore we compiled available literature relevant to commercial probiotic/synbiotic products. Stasiak-Różańska et al.57 compared five commercially available probiotic and synbiotic formulations in Poland, including Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Bifidobacterium BB-12 + FOS, Lactobacillus casei + inulin, Lactobacillus acidophilus + inulin, and Lactobacillus plantarum. The study tested these strains under simulated gastrointestinal conditions using a food matrix. Lactobacillus plantarum proved to be the most resilient, showing significant growth in both gastric and intestinal environments, while the other strains, even those with prebiotics like FOS and inulin, were less resistant57.

Another study by Naissinger da Silva et al.64, analysed 11 commercial formulations (lyophilized/capsules) segregated as industrial (IP), commercial (CP), manipulated (MP) and fermented probiotics (FM). It highlighted the IP formulations demonstrated high initial probiotic concentrations (8 log CFU g−1) and maintained good viability under simulated GI studies. Additionally, synbiotic formulations maintained high initial concentrations (around 10 log CFU g−1) and acceptable viability after digestion (around 7 log CFU g−1), suggesting they could effectively colonize the intestines64.

10 branded formulations (lyophilized/capsules) marketed in Italy were tested for their efficiency in vitro. Lactobacillus species generally resist acidic conditions, but this tolerance varies by species and strain. Single-strain Lactobacillus formulations showed expected resistance, while polymicrobial formulations like Yovis and VSL3 were also resilient, likely due to the complexity of their microbial consortia. In the intestine, probiotics face alkaline conditions and bile salts, which are more harmful to Gram-positive bacteria. Using artificial intestinal fluids to simulate gut conditions, seven probiotic formulations showed significant reductions in viable organisms, but Lactoflorene Plus, Yovis, and VSL3 were the most resistant to intestinal juice65.

Moreover, multiple other researches across the world have been conducted to test the viability and strain concentrations of the commercially produced probiotic/synbiotic formulations in India and Pakistan (5 formulations)66, the Republic of the Philippines and the Republic of Korea (10 formulations)67, United States and Canada (182 formulations)68, India (20 formulations)69. These reports have emphasised the need for manufacturers to ensure that their products maintain sufficient probiotic viability throughout shelf life and digestion, as required by regulatory standards.

In conclusion, the present study stands as preliminary research to formulate and test the efficacy of the synthesised synbiotic formulation prepared with 0.5% chitosan and 8 log CFU/ml L. fermentum culture against heat-processed contaminants like acrylamide (oral administration). Our data highlights the effectiveness of synthesised chitosan-coated L. fermentum nanoparticles against ACR-induced toxicity. Additionally, these findings indicate that our synbiotic formulation successfully preserved gut integrity and microbiota, preventing the manifestation of toxic symptoms associated with ACR exposure in fruit flies. This highlights the significant interaction between ACR and gut microbiota within our experimental model. Additionally, although a plethora of commercial probiotic/synbiotic formulations are available in the market, our formulation differs in key aspects such as—nanoscale product, mono-strain formulation, reliable prebiotic coating with the addition of cryoprotectants, high initial probiotic load, stable shelf life, and resilient viability under simulated GI conditions. Despite the beneficial aspects of the synthesised nano-formulation, we understand the need for sequencing of strains and colonisation studies in higher model systems. The future prospects of our study include a detailed investigation into the protective mechanisms exhibited by the synbiotic formulation via gene and protein expression estimation in higher-order model systems before proceeding to clinical studies.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and cultures

Acrylamide (3 × Crystalline), low molecular weight chitosan (34.5 m Pas, 90.1% degree of deacetylation, ⁓ 50 k Da), glacial acetic acid, yeast extract, propionic acid, orthophosphoric acid, nitro blue tetrazolium salt (NBT), phenazonium Methosulphate (PMS), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced) disodium salt (NADH), potassium chloride, glutathione reduced (GSH), tetrasodium pyrophosphate (TSPP), ethanol, 5, 5-dithiobis 2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB), Abcam TMRE-mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit and, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) were procured from Sisco Research Laboratories, India. Agar–Agar Type -1, dextrose, sodium phosphate monobasic, sodium phosphate dibasic, bovine serum albumin (BSA), phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and methylparaben were purchased from Himedia Pvt. Ltd., India. All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade. Lactobacillus fermentum (MCC 2760) stock was obtained from NCCS, Pune and periodically subcultured in MRS broth (pH 6.5) at 37 °C.

Fabrication and characterisation of chitosan coated probiotic nanoparticles (CSP NPs)

Chitosan-coated probiotic nanoparticles (CSP NPs) were synthesised following a previously reported study with slight modifications48. Briefly, a 0.5% solution of low molecular weight chitosan was prepared with 1% acetic acid and 3 ml of L. fermentum broth (8 log CFU/ml) was mixed with constant stirring. To this, a stoichiometric amount of 1 mg/ml sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) was added dropwise with constant stirring for 2 h at room temperature. The mixture was then sonicated for 30 min and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The pellet was washed thrice with distilled water, then suspended in 10% sucrose and 1% glycerol solution (used as protectants) and stored at − 20 °C. The frozen samples were then lyophilized at − 40 °C and the freeze-dried product was stored at 4 °C for long-term storage. The preparation of chitosan nanoparticles (CS NPs) followed a similar method excluding the addition of the probiotic culture. The overall yield for the above-mentioned process was 220 mg and 370 mg for CSP and CS NPs respectively.

The size and morphology of synthesised CS and CSP NPs were examined using JEM-2100 Plus Hi-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscope (HRTEM), JEOL Japan. The synthesised nanoparticles were suspended in distilled water and coated on the copper grid for further imaging. To analyse the purity of the synthesised nanoparticles, the samples were subjected to Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). The nanoparticle samples in powder form were loaded into the FTIR instrument (Shimadzu, IR tracer 100, Japan) and analysed using ATR mode between 4000 and 400 cm⁻1. A standard chitosan sample was used as a reference to ensure the purity of the synthesised NPs.

The surface charge and particle size of CSP NPs in an aqueous system were then estimated using Malvern/Nano ZS-90 Zeta Sizer. The samples were dispersed in distilled water at 25 °C and suspensions were loaded into the Zeta Sizer for size analysis using dynamic light scattering method. The fluctuations in light scattering intensity caused by the movement of the nanoparticles are used to calculate the hydrodynamic diameter of the particles, which reflects their size distribution in the suspension. Additionally, the electrophoretic light scattering method was employed to measure the zeta potential, which is the electrical potential at the boundary layer surrounding the particles in a suspension. This potential is indicative of the surface charge of the particles and influences their suspension stability.

Viability and stability analysis of CSP NPs

The storage viability of CSP NPs at room temperature was estimated by suspending 1 g of probiotics nanoparticles in 0.01% sodium citrate solution (pH 6) for 10 min. The suspension was then serially diluted and plated on MRS agar plates for overnight incubation. The observed viable colonies were enumerated as log CFU/ml for statistical analysis. The above-mentioned method was repeated every 7th day to establish the storage stability of the synthesised formulation49.

The viability and stability of CSP NPs under simulated gastrointestinal conditions were analysed by suspending 1 g of synthesised nanoparticles and 1 ml of free probiotic culture in a 10 ml simulated gastric fluid (3 mg/ml pepsin; pH 2 adjusted with 1M HCl) with constant stirring on a magnetic stirrer. The release and viability profile of the nano-encapsulated probiotics were estimated by plating 1 ml of the mixture at 0, 60 and 120 h. Then, the nanoparticles and free suspension were pelleted (6000 g; 5 min) and incubated in 9 ml of simulated intestinal fluid (3 mg/ml pancreatin and 1% bile salt; pH 8). The subsequent stability profile was estimated by plating isolates on MRS agar plates post 0, 60, 120 and 180 h of incubation at 37 °C. The viable colonies were enumerated as log CFU/ml for statistical significance50,70.

Drosophila rearing and maintenance

The Drosophila Oregon K wild-type strain was maintained at 25 ± 2 °C and 60% humidity under a 12 h dark–light cycle. Flies were cultured on a standard cornmeal agar medium consisting of cornflour, agar–agar type 1, D-glucose, sugar, and yeast extract. To prevent microbial contamination, the medium was autoclaved and supplemented with antifungal agents including propionic acid, Tego (methyl para hydroxy benzoate dissolved in ethanol), and orthophosphoric acid at 55 °C. As baseline control groups—0.5% chitosan (CS), 10 µg/ml CS NPs and 3 ml of L. fermentum culture (8 log CFU/ml) treatment groups were analysed to comprehend the impact on behaviour and ROS levels. Additionally, 2 mM acrylamide (ACR), 10 µg/ml CSP NPs, and 10 µg/ml CSP NPs + ACR (CSPA) treatment groups were prepared by the stoichiometric addition of respective compounds to the media at 50–55 °C.

Survival and behavioural assay

The lifespan of flies was estimated by transferring twenty-five healthy newborn adult male flies to freshly prepared treatment media. The flies were then constantly monitored and the mortality rate was calculated by tallying the number of dead flies every 24 h. To assess the locomotor functions at the larval stage, male and female flies were added to the respective media for 5 days. The parent flies were then discarded and the vials were carefully maintained till the development of third instar larvae. These larvae were then transferred to an agar plate placed on top of a graph paper and allowed to crawl for one minute. The number of 1 mm grids traversed per minute was represented as the crawling activity for statistical analysis. Similarly, the adult climbing activity was determined by exposing thirty male flies to the respective treatment media for 5 days. The treated flies were then transferred to a climbing assay setup with 3 cm marked vials. The vials were tapped moderately and the percentage of active flies was reported as the number of flies above the 3 cm mark after 10 s71.

Estimation of oxidative stress parameters

Biochemical analysis was carried out with twenty newborn male flies post-5-day exposure to respective treatment groups. Protein estimation of the treated flies was performed following Lowry’s method with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Additionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione-s-transferase (GST) activities were estimated following the previously reported study72,73. Briefly, the treated flies were homogenised in Tris and sodium phosphate buffer for ROS and antioxidant enzyme activity analysis respectively. Stoichiometric quantities of respective reagents were mixed with 100 µl homogenate for further analysis. The fluorescence and absorbance readings were further analysed for statistical analysis.

Estimation of ovarian mitochondrial membrane potential

Thirty female flies were treated with control and treatment media, and their ovaries were dissected to determine their mitochondrial membrane potential. The experiment was slightly modified from the Abcam TMRE-Mitochondrial Membrane Potential experiment Kit. The ovaries were dissected in Schneider’s insect medium, stained with 200 nM TMRE for 15 min in the dark, washed with PBS, and observed using a Leica DM6 fluorescent microscope.

Statistical analysis

All experiments performed in this study were carried out in triplicates to establish statistical significance. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless stated otherwise, Statistical analysis of these data was performed using Graph Pad Prism 6.0 software following Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests to compare the significance of treatment groups with control and ACR, respectively. The significance level for the datasets was set to P < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the SRM SCIF and DBT platform for Advanced Life Science’s support in TEM, fluorescence imaging studies and Zeta analysis. The authors also recognize the support provided by the Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India through the INSPIRE Fellowship program.

Author contributions

S.S.—Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Software, Validation; S.S.M.—Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—review and editing and Supervision.

Data availability

All data sets used and/or generated in this work are obtainable from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pedroza Matute, S. & Iyavoo, S. Exploring the gut microbiota: Lifestyle choices, disease associations, and personal genomics. Front. Nutr.10, 1225120 (2023). 10.3389/fnut.2023.1225120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rein, M. J. et al. Bioavailability of bioactive food compounds: A challenging journey to bioefficacy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.75, 588 (2013). 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04425.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, T. et al. Cytoprotection of probiotics by nanoencapsulation for advanced functions. Trends Food Sci. Technol.142, 104227 (2023). 10.1016/j.tifs.2023.104227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer-Estrada, K., Sandoval-Cuellar, C., Rojas-Muñoz, Y. & Quintanilla-Carvajal, M. X. The modulatory effect of encapsulated bioactives and probiotics on gut microbiota: Improving health status through functional food. Food Funct.14, 32–55 (2023). 10.1039/D2FO02723B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saulnier, D. M., Spinler, J. K., Gibson, G. R. & Versalovic, J. Mechanisms of probiosis and prebiosis: Considerations for enhanced functional foods. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.20, 135 (2009). 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemarajata, P. & Versalovic, J. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: Mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol.6, 39 (2013). 10.1177/1756283X12459294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodoory, V. C. et al. Efficacy of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology165, 1206–1218 (2023). 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph, N. et al. Gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) profiles of normal and overweight school children in Selangor after probiotics administration. J. Funct. Foods57, 103–111 (2019). 10.1016/j.jff.2019.03.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markowiak-Kopeć, P. & Śliżewska, K. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients12, 1107 (2020). 10.3390/nu12041107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagmar, L. et al. Health effects of occupational exposure to acrylamide using hemoglobin adducts as biomarkers of internal dose. Scand J Work Environ Health27, 219–226 (2001). 10.5271/sjweh.608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koszucka, A., Nowak, A., Nowak, I. & Motyl, I. Acrylamide in human diet, its metabolism, toxicity, inactivation and the associated European Union legal regulations in food industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.60, 1677–1692. 10.1080/10408398.2019.1588222 (2020). 10.1080/10408398.2019.1588222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolan, L. C., Matulka, R. A. & Burdock, G. A. Naturally occurring food toxins. Toxins (Basel)2, 2289 (2010). 10.3390/toxins2092289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matoso, V., Bargi-Souza, P., Ivanski, F., Romano, M. A. & Romano, R. M. Acrylamide: A review about its toxic effects in the light of developmental origin of health and disease (DOHaD) concept. Food Chem.283, 422–430. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.054 (2019). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamla, L. & Nisha, P. Acrylamide in deep-fried snacks of India. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill.7, 220–225 (2014). 10.1080/19393210.2014.894141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC, Nceh, DLS & Od. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals Update.

- 16.Lai, S. M. et al. Toxic effect of acrylamide on the development of hippocampal neurons of weaning rats. Neural Regen Res12, 1648–1654 (2017). 10.4103/1673-5374.217345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stagi, S. et al. Increased incidence of precocious and accelerated puberty in females during and after the Italian lockdown for the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Ital. J. Pediatr.46, 165 (2020). 10.1186/s13052-020-00931-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, H. et al. Reproductive toxicity of acrylamide-treated male rats. Reprod. Toxicol.29, 225–230 (2010). 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, Z. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes the necroptosis of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum of acrylamide-exposed rats. Food Chem. Toxicol.171, 113522 (2023). 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yilmaz, B. O., Yildizbayrak, N., Aydin, Y. & Erkan, M. Evidence of acrylamide- and glycidamide-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in Leydig and Sertoli cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.36, 1225–1235 (2017). 10.1177/0960327116686818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, M., Jiao, J., Wang, J., Xia, Z. & Zhang, Y. Characterization of acrylamide-induced oxidative stress and cardiovascular toxicity in zebrafish embryos. J. Hazard Mater.347, 451–460 (2018). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao, S. et al. Protective effect of Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC8014 on acrylamide-induced oxidative damage in rats. Appl. Biol. Chem.63, 1–4 (2020). 10.1186/s13765-020-00527-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alkhalaf, M. I. Diosmin protects against acrylamide-induced toxicity in rats: Roles of oxidative stress and inflammation. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci.32, 1510–1515 (2020). 10.1016/j.jksus.2019.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alturfan, A. A. et al. Resveratrol ameliorates oxidative DNA damage and protects against acrylamide-induced oxidative stress in rats. Mol. Biol. Rep.39, 4589–4596 (2012). 10.1007/s11033-011-1249-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westfall, S., Iqbal, U., Sebastian, M. & Pasinetti, G. M. Gut Microbiota Mediated Allostasis Prevents Stress-Induced Neuroinflammatory Risk Factors of Alzheimer’s Disease. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science Vol. 168 (Elsevier, 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storelli, G. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum promotes drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab.14, 403–414 (2011). 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivas-Jimenez, L. et al. Evaluation of acrylamide-removing properties of two Lactobacillus strains under simulated gastrointestinal conditions using a dynamic system. Microbiol. Res.190, 19–26 (2016). 10.1016/j.micres.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph, J. J., Sangeetha, D. & Gomathi, T. Sunitinib loaded chitosan nanoparticles formulation and its evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.82, 952–958 (2016). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.10.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad, N., Khan, M. R., Palanisamy, S. & Mohandoss, S. Anticancer drug-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for in vitro release, promoting antibacterial and anticancer activities. Polymers (Basel)15, 3925 (2023). 10.3390/polym15193925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogol, B. A. & Gökmen, V. Thermal process contaminants: Acrylamide, chloropropanols and furan. Curr. Opin. Food Sci.7, 86–92 (2016). 10.1016/j.cofs.2016.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yousef, M. I. & El-Demerdash, F. M. Acrylamide-induced oxidative stress and biochemical perturbations in rats. Toxicology219, 133–141 (2006). 10.1016/j.tox.2005.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khiralla, G., Elhariry, H. & Selim, S. M. Chitosan-stabilized selenium nanoparticles attenuate acrylamide-induced brain injury in rats. J. Food Biochem.44, e13413 (2020). 10.1111/jfbc.13413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh, M. P., Jakhar, R. & Kang, S. C. BiotransformaMorin hydrate attenuates the acrylamide-induced imbalance in antioxidant enzymes in a murine model. Int. J. Mol. Med.36, 992–1000 (2015). 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albalawi, A. et al. Carnosic acid attenuates acrylamide-induced retinal toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Exp. Eye Res.175, 103–114 (2018). 10.1016/j.exer.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan, X. et al. Acrylamide aggravates cognitive deficits at night period via the gut–brain axis by reprogramming the brain circadian clock. Arch Toxicol.93, 467–486 (2019). 10.1007/s00204-018-2340-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yue, Z. et al. Acrylamide induced glucose metabolism disorder in rats involves gut microbiota dysbiosis and changed bile acids metabolism. Food Res. Int.157, 111405 (2022). 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muszyński, S. et al. Maternal acrylamide exposure changes intestinal epithelium, immunolocalization of leptin and ghrelin and their receptors, and gut barrier in weaned offspring. Sci. Rep.2023(13), 1–16 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schabacker, J., Schwend, T. & Wink, M. Reduction of acrylamide uptake by dietary proteins in a Caco-2 gut model. J. Agric. Food Chem.52, 4021–4025 (2004). 10.1021/jf035238w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amirshahrokhi, K. Acrylamide exposure aggravates the development of ulcerative colitis in mice through activation of NF-κB, inflammatory cytokines, iNOS, and oxidative stress. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci.24, 312 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownlee, I. A., Uranga, J. A. & Palus, K. Dietary exposure to acrylamide has negative effects on the gastrointestinal tract: A review. Nutrients16, 2032 (2024). 10.3390/nu16132032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao, Y. et al. Lactobacillus fermentum and its potential immunomodulatory properties. J. Funct. Foods56, 21–32 (2019). 10.1016/j.jff.2019.02.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dempsey, E. & Corr, S. C. Lactobacillus spp. for gastrointestinal health: Current and future perspectives. Front. Immunol.13, 840245 (2022). 10.3389/fimmu.2022.840245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lacerda, D. C. et al. Potential role of Limosilactobacillus fermentum as a probiotic with anti-diabetic properties: A review. World J. Diabetes13, 717 (2022). 10.4239/wjd.v13.i9.717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Gregorio, A. et al. Protective Effect of Limosilactobacillus fermentum ME-3 against the Increase in Paracellular Permeability Induced by Chemotherapy or Inflammatory Conditions in Caco-2 Cell Models. Int J Mol Sci24, 6225 (2023). 10.3390/ijms24076225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou, Y.-C., Ho, P.-Y., Chen, W.-J., Wu, S.-H. & Pan, M.-H. Lactobacillus fermentum V3 ameliorates colitis-associated tumorigenesis by modulating the gut microbiome. Am. J. Cancer Res.10, 1170 (2020). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozen, M., Piloquet, H. & Schaubeck, M. Limosilactobacillus fermentum CECT5716: Clinical potential of a probiotic strain isolated from human milk. Nutrients15, 2207 (2023). 10.3390/nu15092207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guan, Z. & Feng, Q. Chitosan and chitooligosaccharide: The promising non-plant-derived prebiotics with multiple biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 6761 (2022). 10.3390/ijms23126761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunasangkaran, G., Ravi, A. K., Arumugam, V. A. & Muthukrishnan, S. Preparation, characterization, and anticancer efficacy of chitosan, chitosan encapsulated piperine and probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum (MTCC-1407), and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (MTCC-1423) nanoparticles. Bionanoscience12, 527–539 (2022). 10.1007/s12668-022-00961-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebrahimnejad, P., Khavarpour, M. & Khalili, S. Survival of Lactobacillus acidophilus as probiotic bacteria using chitosan nanoparticles. Int. J. Eng. Trans. A Basics30, 456–463 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alkushi, A. G. et al. Probiotics-loaded nanoparticles attenuated colon inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in colitis. Sci. Rep.12, 1–19 (2022). 10.1038/s41598-022-08915-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandey, R. P., Gunjan, H., Mukherjee, R. & Chang, C. M. Nanocarrier-mediated probiotic delivery: A systematic meta-analysis assessing the biological effects. Sci. Rep.14, 1–11 (2024). 10.1038/s41598-023-50972-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alkushi, A. G. et al. Multi-strain-probiotic-loaded nanoparticles reduced colon inflammation and orchestrated the expressions of tight junction, NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 genes in dss-induced colitis model. Pharmaceutics14, 1183 (2022). 10.3390/pharmaceutics14061183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pupa, P. et al. The efficacy of three double-microencapsulation methods for preservation of probiotic bacteria. Sci. Rep.11, 13753 (2021). 10.1038/s41598-021-93263-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar, N. et al. Preparation of probiotic-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles and in vitro survival in gastrointestinal conditions. BIO Web Conf.86, 01051 (2024). 10.1051/bioconf/20248601051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim, S. et al. Novel modified probiotic gold nanoparticles loaded with ginsenoside CK exerts an anti-inflammation effect via NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathways. Arab. J. Chem.17, 105650 (2024). 10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang, Y. N. et al. The high permeability of nanocarriers crossing the enterocyte layer by regulation of the surface zonal pattern. Molecules25, 919 (2020). 10.3390/molecules25040919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stasiak-Różańska, L., Berthold-Pluta, A., Pluta, A. S., Dasiewicz, K. & Garbowska, M. Effect of simulated gastrointestinal tract conditions on survivability of probiotic bacteria present in commercial preparations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18, 1–17 (2021). 10.3390/ijerph18031108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gómez, E. et al. Impact of probiotics on development and behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster -a potential in vivo model to assess probiotics. Benef Microbes10, 179–188 (2019). 10.3920/BM2018.0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Westfall, S., Lomis, N. & Prakash, S. Longevity extension in Drosophila through gut-brain communication. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-018-25382-z (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-25382-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Westfall, S., Lomis, N. & Prakash, S. Ferulic acid produced by Lactobacillus fermentum influences developmental growth through a dTOR-mediated mechanism. Mol. Biotechnol.61, 1 (2019). 10.1007/s12033-018-0119-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poinsot, P. et al. Probiotic from human breast milk, Lactobacillus fermentum, promotes growth in animal model of chronic malnutrition. Pediatr. Res.10.1038/s41390-020-0774-0 (2020). 10.1038/s41390-020-0774-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jang, Y. J., Kim, W. K., Han, D. H., Lee, K. & Ko, G. Lactobacillus fermentum species ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by regulating the immune response and altering gut microbiota. Gut Microbes10, 696–711. 10.1080/19490976.2019.1589281 (2019). 10.1080/19490976.2019.1589281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thumu, S. C. R. & Halami, P. M. In vivo safety assessment of Lactobacillus fermentum strains, evaluation of their cholesterol-lowering ability and intestinal microbial modulation. J. Sci. Food Agric.100, 705–713 (2020). 10.1002/jsfa.10071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naissinger da Silva, M. et al. In vitro test to evaluate survival in the gastrointestinal tract of commercial probiotics. Curr. Res. Food Sci.4, 320–325 (2021). 10.1016/j.crfs.2021.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vecchione, A. et al. Compositional quality and potential gastrointestinal behavior of probiotic products commercialized in Italy. Front. Med. (Lausanne)5, 59 (2018). 10.3389/fmed.2018.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patrone, V., Molinari, P. & Morelli, L. Microbiological and molecular characterization of commercially available probiotics containing Bacillus clausii from India and Pakistan. Int. J. Food Microbiol.237, 92–97 (2016). 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dioso, C. M. et al. Do your kids get what you paid for? Evaluation of commercially available probiotic products intended for children in the Republic of the Philippines and the Republic of Korea. Foods9, 1229 (2020). 10.3390/foods9091229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shehata, H. R. & Newmaster, S. G. Combined targeted and non-targeted PCR based methods reveal high levels of compliance in probiotic products sold as dietary supplements in United States and Canada. Front. Microbiol.11, 531086 (2020). 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kesavelu, D., Rohit, A., Karunasagar, I. & Karunasagar, I. Composition and laboratory correlation of commercial probiotics in India. Cureus12, e11334 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golnari, M., Behbahani, M. & Mohabatkar, H. Comparative survival study of Bacillus coagulans and Enterococcus faecium microencapsulated in chitosan-alginate nanoparticles in simulated gastrointestinal condition. LWT197, 115930 (2024). 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.115930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sundararajan, V., Dan, P., Kumar, A. & Venkatasubbu, G. D. Applied surface science drosophila melanogaster as an in vivo model to study the potential toxicity of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci.490, 70–80 (2019). 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.06.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Senthilkumar, S. et al. Developmental and behavioural toxicity induced by acrylamide exposure and amelioration using phytochemicals in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Hazard Mater.394, 122533 (2020). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siddique, Y. H. et al. Toxic potential of copper-doped ZnO nanoparticles in Drosophila melanogaster (Oregon R). Toxicol. Mech. Methods25, 425–432 (2015). 10.3109/15376516.2015.1045653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data sets used and/or generated in this work are obtainable from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.