Abstract

tRNAs have recently gained attention for their novel regulatory roles in translation and for their diverse functions beyond translation. One of the most remarkable aspects of tRNA biogenesis is the incorporation of various chemical modifications, ranging from simple base or ribose methylation to more complex hypermodifications such as formation of queuosine and wybutosine. Some tRNAs are transcribed as intron-containing pre-tRNAs. While the majority of these modifications occur independently of introns, some are catalyzed in an intron-inhibitory manner, and in certain cases, they occur in an intron-dependent manner. This review focuses on pre-tRNA modification, including intron-containing pre-tRNA, in both intron-inhibitory and intron-dependent fashions. Any perturbations in the modification and processing of tRNAs may lead to a range of diseases and disorders, highlighting the importance of understanding these mechanisms in molecular biology and medicine.

Keywords: RNA modification, tRNA, intron, pre-tRNA, processing, enzyme

1 Introduction

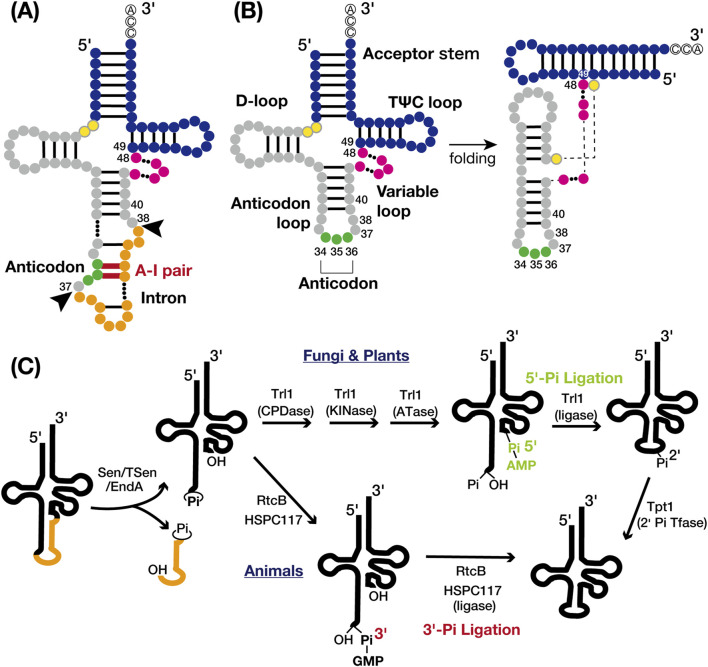

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides long, forming a cloverleaf shape that folds into an L-shaped structure (Figures 1A, B). They undergo over 100 post-transcriptional modifications with 8–13 per molecule (Machnicka et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2022; Cappannini et al., 2024). Modifications within the anticodon loop are essential for recognition by cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) and mRNA decoding accuracy, while modifications outside this region contribute to maintaining the structural integrity and quality control of tRNAs (Barraud and Tisné, 2019; Phizicky and Hopper, 2023). Recent advances in tRNA epitranscriptomics have mapped tRNA modifications and uncovered the roles of modification enzymes in various health and disease (Abbott et al., 2014; Kirchner and Ignatova, 2015; Ramos and Fu, 2019; Suzuki, 2021; Cerneckis et al., 2022; Sekulovski and Trowitzsch, 2022; Añazco-Guenkova et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024). Comprehensive reviews further explore these discoveries, detailing the functions of newly identified tRNA modifications including the roles of tRNA fragments (Kessler et al., 2018b; Lyons et al., 2018; Schimmel, 2018; Krutyhołowa et al., 2019; George et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022; Phizicky and Hopper, 2023). This review explores the roles of tRNA introns in chemical modifications. In prokaryotes, tRNAs are often synthesized as multimeric precursors, processed to monomeric forms, trimmed 5′-3′, with CCA nucleotides at the 3′ end either encoded or added post-transcriptionally, and undergo nucleotide modifications (Mohanty and Kushner, 2019). In archaea and eukaryotes, tRNA processing starts with 5′-3′ trimming, followed by CCA addition, nucleotide modifications, and, for intron-containing pre-tRNAs, subsequent splicing of introns. The relationship between post-transcriptional modification and tRNA introns was pioneered and well-documented in the 1980s and 1990s (Johnson and Abelson, 1983; Strobel and Abelson, 1986; Choffat et al., 1988; Grosjean et al., 1997; Jiang et al., 1997; Motorin et al., 1998). However, the mechanisms involving intron-inhibitory, intron-dependent, and intron-insensitive enzymes proposed by (Grosjean et al., 1997) remain inadequately explained. Recent advancements in the field of modifications are likely to provide new insights into this complex and fascinating area of study, necessitating a revisitation of this topic.

FIGURE 1.

tRNA structures and tRNA splicing pathways. (A) Secondary structure of intron-containing pre-tRNA: the acceptor stem and TΨC loop (blue), D-loop and anticodon loop (gray), variable loop (pink), anticodon (green), and intron (orange). The intermediate nucleotides between the acceptor stem and D-loop are yellow with grey circles. Nucleotide base pairing is represented by black lines, with the anticodon-intron (A–I) pair highlighted in red. The nucleotide numbers indicate the positions adjacent to the intron insertion sites (positions 37/38) and the locations of known tRNA intron-dependent modification positions, excluding the anticodon (positions 34–36). Black arrows indicate the canonical intron insertion site. (B) Secondary (left) and tertiary (right) structures of mature tRNA are shown with the same color codes and nucleotide numbers as in A. (C) Cleavage of the tRNA splice site (left) and two distinct tRNA ligation pathways: the 5′-phosphate pathway (upper right) and the 3′-phosphate pathway (lower right). The tRNA body is represented in black and the intron in orange. Proteins involved in each chemical reaction are also shown.

2 tRNA intron and splicing

2.1 tRNA intron

tRNA introns were initially identified in yeast tRNATyr genes by Goodman et al. in 1977 (Goodman et al., 1977) and are now widely recognized in both archaea and eukaryotes (Chan and Lowe, 2016). In bacteria, tRNA typically lacks introns spliced by specialized proteinaceous enzymes. Instead, the self-splicing group I introns, which use a mechanism related to mRNA splicing, are found in the anticodon region in cyanobacteria and some alpha- and beta-proteobacteria (Reinhold-Hurek and Shub, 1992; Tanner and Cech, 1996). In archaea, an estimated 15% of tRNA genes contain tRNA introns. Of those, approximately 75% are at the canonical 37/38 position, one nucleotide 3′ from the anticodon (Figure 1A). The remaining 25% are dispersed across various sites in tRNA genes, with some containing multiple introns predicted in silico (Marck and Grosjean, 2003; Sugahara et al., 2007; Tocchini-Valentini et al., 2009; 2011). In eukaryotes, 5%–25% of tRNA genes harbor introns, which are predominantly single and consistently at the canonical position 37/38 (Chan and Lowe, 2016; Hayne et al., 2023; Phizicky and Hopper, 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). These introns form an A-I pair that disrupts codon-anticodon binding during translation (Bufardeci et al., 1993), making tRNA splicing essential for pre-tRNA maturation (Figure 1A). The canonical position of tRNA introns is believed to be ancient (Fujishima and Kanai, 2014), suggesting that eukaryotes have retained tRNA introns over long evolutionary periods.

2.2 Conservation and diversity of tRNA splicing by proteins

tRNA splicing facilitated by specific endonucleases and ligases, involves key components which present across archaea to eukaryotes, albeit with variations in specific mechanisms. In archaea, tRNA splicing endonucleases and tRNA ligase process all introns, including those in pre-rRNAs and pre-mRNAs (Tocchini-Valentini et al., 2011; Tocchini-Valentini and Tocchini-Valentini, 2021). Most endonucleases recognize a structural motif called the bulge-helix-bulge (BHB) motif. In contrast, eukaryotes utilize a tRNA endonuclease (Sen/TSen) consisting of four conserved subunits, which cleaves splice sites via the “molecular ruler” mechanism (Trotta et al., 1997; Akama et al., 2000; Paushkin et al., 2004; Phizicky and Hopper, 2023). Two distinct ligation pathways exist for tRNA processing in both archaea and eukaryotes, categorized by the origin of the phosphate linking the 5′- and 3′-exons: the 5′-phosphate pathway and the 3′-phosphate pathway (Figure 1C). In eukaryotes, 5′-phosphate RNA ligases are common in fungi and plants, while 3′-phosphate RNA ligases are used in animals (Tocchini-Valentini et al., 2005; Popow et al., 2012; Yoshihisa, 2014; Phizicky and Hopper, 2023). The location of tRNA splicing varies among eukaryotes; in vertebrates and plants, tRNA splicing occurs within the nucleus, whereas in yeast, it occurs near the mitochondria due to different enzyme distributions (Melton et al., 1980; Yoshihisa et al., 2003; 2007; Paushkin et al., 2004; Mee et al., 2005). This spatial compartmentalization enables precise timing of chemical modifications during tRNA maturation, exhibiting variability across organisms and even within different tRNA genes of the same organism (Phizicky and Hopper, 2023). The rates of intracellular transport may influence the extent of modification (Kessler et al., 2018b). The complexity of this process is further amplified by the intricate nature of nucleoside modifications (Barraud and Tisné, 2019).

3 Modifications and tRNA introns

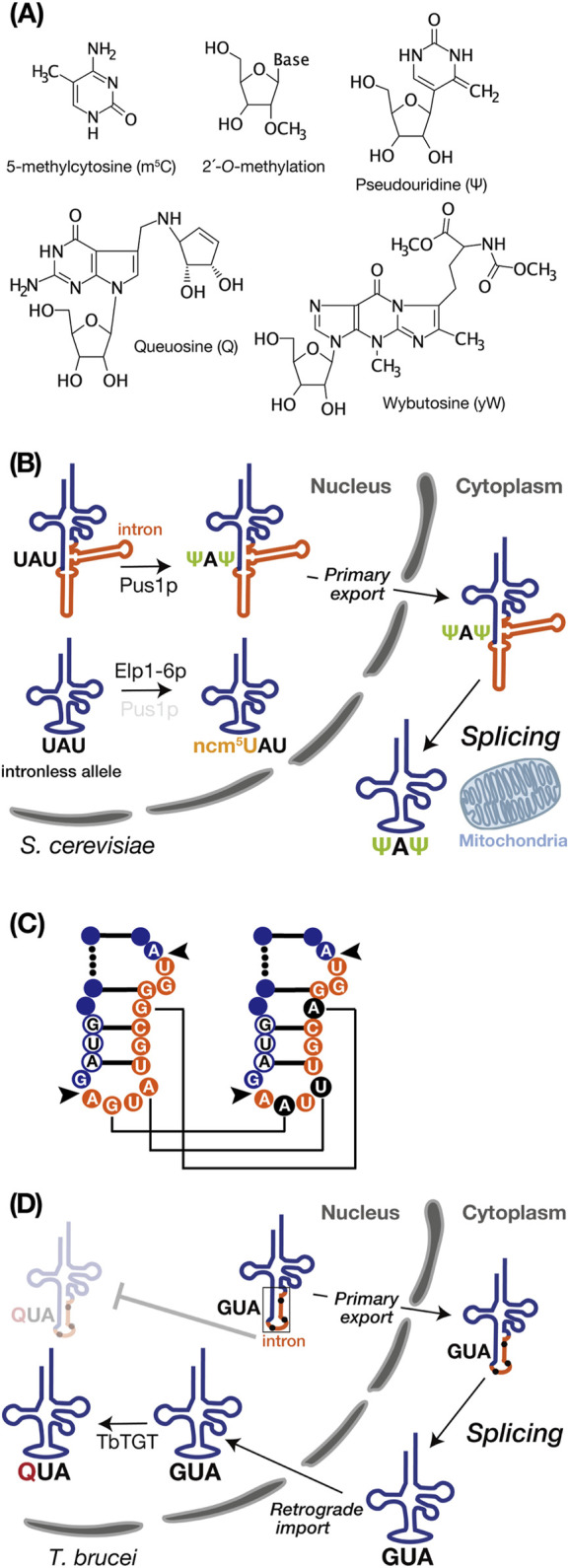

Most of the diversity in tRNA modifications is concentrated within the anticodon loop, where these modifications are pivotal for accurately decoding mRNA at the ribosomal A-site (Machnicka et al., 2014). In intron-containing pre-tRNAs, the majority of modifications occur independently of introns, whether within or outside the anticodon-loop, some modifications are catalyzed only in an intron-dependent manner, and in specific cases, modifications occur in an intron-inhibitory manner. The following instances highlight these modifications (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

tRNA intron and modifications. (A) Chemical structures of the RNA modifications discussed in this review, created using MarvinSketch (ChemAxion Ltd.). (B) tRNA intron-dependent modification. In S. cerevisiae, pre-tRNAIle UAU undergoes intron-dependent pseudouridylation (Ψ) at U34 and U36 by Pus1p in the nucleus. Subsequently, the modified pre-tRNA is exported to the cytoplasm for splicing near the mitochondria. In the intronless allele, on the other hand, pre-tRNAIle UAU lacking an intron undergoes modification at position 34 by the Elp1-6p complex to convert ncm5U. (C) Schematic representation of non-canonical base editing of the intron in Trypanosoma brucei pre-tRNATyr GUA. The 11-nucleotide intron is shown in orange, and the GUA anticodon is depicted in white with a blue circle. Black arrows indicate the intron insertion sites. In the right panel, edited nucleotides are highlighted in black. Editing is essential for proper intron processing by the tRNA endonuclease (as shown in D). (D) In Trypanosoma brucei, the intron-containing pre-tRNATyr GUA with edited intron, as shown on the right side of C, is exported to the cytoplasm as the primary export substrate. After cytoplasmic splicing, the post-spliced pre-tRNATyr GUA undergoes intron-inhibitory modification with queuosine (Q) by Trypanosoma brucei tRNA-guanine transglycosylase (TbTGT).

3.1 Pseudouridylation

Pseudouridylation of uridine (Ψ) is a common RNA modification catalyzed by pseudouridine synthase (Pus) enzymes across numerous noncoding and protein-coding RNA substrates (Rintala-Dempsey and Kothe, 2017; Purchal et al., 2022). Pseudouridine enables robust base pairing to A with stiffening the sugar-phosphate backbone and enhancing stacking interactions to adjacent base pairs, which yields genuine Watson–Crick-like base pairing as strong as a C-G pair (Davis, 1995; Spenkuch et al., 2014). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pus1p pseudouridylates U34 and U36 in the anticodon of intron-containing pre-tRNAIle UAU but not its spliced form (Szweykowska-Kulinska et al., 1994; Simos et al., 1996; Motorin et al., 1998). In vitro biochemical studies revealed that removing either the acceptor stem, the TΨ loop, or the D stem-loop from the pre-tRNA did not affect the formation of Ψ34 and Ψ36, and even the anticodon stem-loop interrupted by the intron effectively serves as a substrate (Szweykowska-Kulinska et al., 1994). Structurally, Pus1p specifically recognizes the anticodon region only when the anticodon and the intron form a double helix (Motorin et al., 1998). This was also confirmed in vivo by systematic intron removal from the yeast tRNA genes (Hayashi et al., 2019). Interestingly, in tRNAIle UAU of the intronless mutant, some of U34 are aberrantly converted into 5-carbamoylmethyl U34 (ncm5U34). Notably, in the pus1Δ strain where intron-containing pre-tRNAIle UAU is transcribed, the ncm5U34 modification in tRNAIle UAU was also observed. Therefore, the intron in tRNAIle UAU serves as a positive factor for Ψ34 formation while concurrently preventing ncm5U34 formation (Figure 2B). Because the Elp complex (Elp1–6p), responsible for ncm5U34 formation in tRNAs, is localized in the nucleus (Huang et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2008) and does not recognize intron-containing pre-tRNAIle UAU (Yoshihisa et al., 2003), this modification in pus1Δ cells only occurs after splicing (Hayashi et al., 2019). Considering that the absence of Pus1p impairs the nuclear export of tRNAs, Pus1p-dependent tRNA modification seems to facilitate efficient nuclear export of certain tRNAs (Großhans et al., 2001). Thus, the intron-dependent Ψ34 modification or interaction with Pus1p may play some roles in pre-tRNAIle UAU export for tRNA splicing near mitochondria.

Another example of intron-dependent pseudouridylation is Ψ35 introduction to tRNATyr GUA by Pus7p (van Tol and Beier, 1988; Motorin et al., 1998; Behm-Ansmant et al., 2003; Urban et al., 2009). Pus7p incorporates pseudouridines into a particularly diverse set of RNAs, including tRNA, small nuclear RNA (snRNA), rRNA, and mRNA (Behm-Ansmant et al., 2003; Carlile et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2014; Guzzi et al., 2018). The presence of Ψ35 in tRNA is determined by the nucleotide sequence around U35 and is affected by the length of the intron rather than its specific structural characteristics (Szweykowska-Kulinska and Beier, 1992). tRNATyr GUA with Ψ35 often acts as a suppressor for amber (UAG) and ochre (UAA) stop codons (Johnson and Abelson, 1983; Zerfass and Beier, 1992). The absence of Ψ35 significantly reduces its near-cognate suppressor activity at these stop codons but does not impact the decoding of cognate tyrosine codons (Johnson and Abelson, 1983; Blanchet et al., 2018). Additionally, the combination of Ψ35 and intron-independent A37 isopentenylation (i6A37) by Mod5p is crucial for effective stop codon suppression (Blanchet et al., 2018). While Ψ35 primarily aids in recognizing the UAG codon, i6A37 is more influential in readthrough of the UAA stop codon. Importantly, Ψ35-containing tRNATyr GUA does not distinguish between the two synonymous tyrosine codons, UAU and UAC (Blanchet et al., 2018). Thus, the existence of tRNATyr GUA introns seems to be meaningful for amber/ochre suppression. Considering that nonsense mutations, associated with nearly 1,000 serious genetic disorders, account for 10%–15% of all genetic defects that lead to disease (Mort et al., 2008), the role of suppressor tRNATyr in amber/ochre suppression may have significant contribute to preventing and treating these diseases.

3.2 Base methylation

Methylations of tRNA molecules influence various aspects such as their folding dynamics, stability under heat, maturation process, and protection against cleavage, while also priming them for the synthesis of subsequent modifications (Hori, 2014; Zhang et al., 2022). Eukaryotic tRNA methyltransferases (TRMs) commonly employ S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor (Lesnik et al., 2015). The formation of 5-methylcytosine at position 34 (m5C34) of tRNALeu CAA requires its intron and occurs in the nucleus both in S. cerevisiae and in human (Motorin and Grosjean, 1999; Auxilien et al., 2012). The structure of a prolonged anticodon stem and the nucleotide sequence surrounding the position to be modified are crucial for m5C34 formation in pre-tRNALeu CAA (Brzezicha et al., 2006). The wobble base modification of tRNALeu CAA is implicated in regulating translation. In yeast, under oxidative stress conditions, there is an upregulation of the m5C34 modification, which enhances translation of the corresponding Leu (UUG) codons (Chan et al., 2012). In human, m5C34 is partially hydroxylated to form 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-O-methylcytidine (hm5C34), which then undergoes further oxidation to yield 5-formylcytidine (f5C34), and their 2′-O-methylation (f5Cm34/hm5Cm34) (Kawarada et al., 2017). Pathogenic mutations in FTSJ1 and TRM4/NSUN2, involving in the process, are associated with intellectual disabilities. Dysregulation of protein synthesis due to the loss of f5Cm34/hm5Cm34 in cytoplasmic tRNALeu CAA may contribute to the molecular pathogenesis of these diseases (Kawarada et al., 2017). Additionally, in yeast pre-tRNAPhe GAA, an intron-dependent methylation by Trm4p occurs outside the anticodon, but in the anticodon stem-loop, at position C40 (Jiang et al., 1997; Motorin and Grosjean, 1999). This m5C40 modification is crucial for the spatial organization of the anticodon stem-loop and the formation of the Mg2+ binding pocket (Agris, 1996).

In contrast, in S. cerevisiae, Trm4p methylates on C48 and C49 in an intron-independent manner. Typically, this modification occurs at either C48 or C49 alone, but not simultaneously at both sites (Grosjean et al., 1997; Motorin et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2023). This pattern of methylation is conserved in humans, where intron-independent m5C48 formation on tRNALeu CAA is also observed (Auxilien et al., 2012). Thus, m5C40 of yeast tRNAPhe GAA and m5C34 of yeast and human tRNALeu CAA are introduced intron-dependently, while m5C49 of yeast tRNAPhe GAA and m5C48 of human tRNALeu CAA are intron-independently. Consequently, Trm4p introduces modifications within the same molecules using different recognition mechanisms.

In a fission yeast S. pombe and a dicotyledon Arabidopsis thaliana, as well as some other plants, there are two homologs of Trm4p/NSun2 termed Trm4a and Trm4b (Becker et al., 2012; David et al., 2017). Schizosaccharomyces pombe methylases exhibit a clear division of labor in vivo: Trm4a methylates all C48 residues and also C34 in tRNALeu CAA and tRNAPro CGG, whereas Trm4b specifically methylates C49 (Müller et al., 2019). In vitro, however, Trm4b acts on C34 intron-dependently though inefficiently (Müller et al., 2019), suggesting that such Trm4b activity on C34 is somehow completely suppressed in vivo.

3.3 Ribose methylation: 2′-O-methylation

In a certain case, tRNA introns act as guiding elements that designate specific nucleotide positions for modifications. In archaea and eukaryotes, most 2′-O-methylations in ribosomal and other RNAs are directed by box C/D and box H/ACA small nucleolar RNPs (snoRNPs), respectively (Watkins and Bohnsack, 2012; Kufel and Grzechnik, 2019; Breuer et al., 2021). Archaea present an additional scenario where a functional unit for tRNA modification, such as a box C/D small RNA, is embedded within the tRNA’s intron, as seen in the tRNATrp precursor of Haloferax volcanii and other Euryarchaeota (D’Orval et al., 2001). This intronic segment, or the excised intron, facilitates 2′-O-methylation of C34 and U39 in trans (Singh et al., 2004). Deleting the box C/D RNA-containing intron abolishes RNA-guided 2′-O methylations of C34 and U39 without affecting growth under standard conditions (Joardar et al., 2008).

3.4 Queuosine

Queuosine (Q) is a hypermodified nucleotide derived from guanosine, incorporated at the wobble anticodon position 34 of tRNAs bearing the 5′-GUN-3′ (N = any base) anticodon sequence, which decode codons for Asn, Asp, His, and Tyr (Fergus et al., 2015). Q is present in both bacteria and eukaryotes, but it is only synthesized de novo in bacteria. Therefore, eukaryotes entirely rely Q supply on external sources originated from bacteria (Fergus et al., 2015). In T. brucei, only the cytoplasmically spliced pre-tRNATyr GUA, transported back to the nucleus via retrograde transport pathway, can undergoes Q modification facilitated by tRNA-guanine transglycosylase which localized in the nucleus (Kessler et al., 2018a) (Figure 2D). Q-modified tRNATyr GUA is subsequently re-exported to the cytoplasm for translation, and a portion is selectively imported into mitochondria (Hegedűsová et al., 2019; Kulkarni et al., 2021). Due to varying steady-state levels of Q among different life cycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei, this modification has significant roles in codon selection in these parasite stages (Dixit et al., 2021). Interestingly, these sequential processing events begin with non-canonical editing, including guanosine-to-adenosine transitions (G to A) and an adenosine-to-uridine transversion (A to U), on the intron of pre-tRNATyr GUA, which is essential for maturation because recognition and splicing by the SEN complex occur exclusively with the edited form of pre-tRNATyr GUA (Rubio et al., 2013) (Figure 2C). So far, mechanisms behind these non-canonical intron editing are ambiguous, but they appear to involve neither enzymatic activity nor deamination. Instead, they are likely related to nucleotide or base replacement (Rubio et al., 2013). Collectively, the T. brucei tRNATyr GUA intron negatively governs Q modification as a barrier, and splicing of this intron is under the control of nucleotide editing.

3.5 Wybutosine

Wybutosine base (yW) is a complex nucleotide on tRNAs originating from a genetically encoded guanosine residue, undergoing a transformation into a fluorescent tricyclic fused aromatic base (Noma et al., 2006; Perche-Letuvée et al., 2014). Typically found at position 37 of eukaryotic and archaeal tRNAPhe GAA, yW and its derivatives stabilize the first base pair of the codon-anticodon duplex in the ribosomal A site through base stacking (Konevega et al., 2004). Although yW does not significantly affect the aminoacylation of tRNAPhe GAA (Thiebe and Zachau, 1968), its absence promotes frameshifting and impacts viral RNA replication (Waas et al., 2007). Similarly to Q modification in T. brucei tRNATyr GUA, only spliced pre-tRNAPhe GAA in S. cerevisiae undergoes yW modification in S. cerevisiae (Ohira and Suzuki, 2011). After splicing, tRNAPhe GAA is re-imported into the nucleus where Trm5p catalyzes the formation of m1G37, the first step of yW formation. The resulting tRNATyr intermediate is then exported back to the cytoplasm, where the remaining enzymes such as Tyw1p, Tyw2p, Tyw3p, and Tyw4p complete yW synthesis. Thus, tRNAPhe GAA intron regulates proper timing of yW modification steps during nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of tRNAPhe GAA. Structural analysis of Pyrococcus abyssi Trm5a reveals that the enzyme recognizes the overall shape of tRNA (Wang et al., 2017), suggesting that the intron-containing pre-tRNAPhe GAA, with its disrupted anticodon-loop structure due to the A-I pair, could escape from recognition by Trm5p before splicing.

4 Conclusion

A number of tRNA modifications, especially those located outside the anticodon region, occur independently of the presence or absence of intron (Grosjean et al., 1997). A study of yeast intronless alleles revealed that none of the strains displayed severe growth defects under normal conditions, and the majority maintained relatively mature tRNA expression, aminoacylation status, and general translation capacity (Hayashi et al., 2019). Thus, tRNA introns may have a limited impact on tRNA biology, including nucleotide modifications. However, certain modification enzymes selectively recognize targets and modify specific sites within the same tRNA molecules through either an intron-dependent or -independent mechanism. Unlike mRNA introns, which lead to the diversity of mature mRNA sequences through splicing, tRNA introns do not contribute to tRNA primary sequence diversity. Since RNA modifications provide an additional layer of regulation beyond the primary sequence, organisms may have evolved intron-dependent or intron-inhibitory modifications to delicately adjust tRNA quantity and/or function by controlling the order and timing of certain modifications during tRNA maturation. In a different view, intron-insensitive tRNA modifications might serve more fundamental and essential roles on tRNA. The precise mechanism behind this selectivity involving introns remains incompletely understood. Further investigation into regulatory roles of introns in these modifications holds significant potential for discovery. How can individual modifications be distinguished as intron-dependent or -independent? What explains the conservation of intron-dependent modifications in specific tRNA molecules across different species, despite variations in their tRNA intron sequences? How did modification enzymes evolve to accommodate changes in intron sequences? Addressing these questions would not only enhance our comprehension of fundamental molecular mechanisms of tRNA maturation but also advance our understanding of evolutionary adaptations of this complicated process. Additionally, these insights may inform developments in treatments and drugs targeting tRNA modifications in diseases.

Acknowledgments

I thank to Prof. Tohru Yoshihisa (University of Hyogo, Japan) for his insightful critiques and constructive comments on this manuscript.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by Hyogo Science and Technology Association, Japan [6082] to SH.

Author contributions

SH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abbott J. A., Francklyn C. S., Robey-Bond S. M. (2014). Transfer RNA and human disease. Front. Genet. 5, 158. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agris P. F. (1996). The importance of being modified: roles of modified nucleosides and Mg2+ in RNA structure and function. Prog. Nucleic Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 53, 79–129. 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akama K., Junker V., Beier H. (2000). Identification of two catalytic subunits of tRNA splicing endonuclease from Arabidopsis thaliana . Gene 257, 177–185. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00408-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Añazco-Guenkova A. M., Miguel-López B., Monteagudo-García Ó., García-Vílchez R., Blanco S. (2024). The impact of tRNA modifications on translation in cancer: identifying novel therapeutic avenues. Nar. Cancer 6, zcae012. 10.1093/narcan/zcae012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auxilien S., Guérineau V., Szweykowska-Kuliñska Z., Golinelli-Pimpaneau B. (2012). The human tRNA m5C methyltransferase Misu is multisite-specific. RNA Biol. 9, 1331–1338. 10.4161/rna.22180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud P., Tisné C. (2019). To be or not to be modified: miscellaneous aspects influencing nucleotide modifications in tRNAs. IUBMB Life 71, 1126–1140. 10.1002/iub.2041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M., Müller S., Nellen W., Jurkowski T. P., Jeltsch A., Ehrenhofer-Murray A. E. (2012). Pmt1, a Dnmt2 homolog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, mediates tRNA methylation in response to nutrient signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 11648–11658. 10.1093/nar/gks956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm-Ansmant I., Urban A., Ma X., Yu Y.-T., Motorin Y., Branlant C. (2003). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae U2 snRNA:pseudouridine-synthase Pus7p is a novel multisite–multisubstrate RNA:Ψ-synthase also acting on tRNAs. RNA 9, 1371–1382. 10.1261/rna.5520403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet S., Cornu D., Hatin I., Grosjean H., Bertin P., Namy O. (2018). Deciphering the reading of the genetic code by near-cognate tRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, 3018–3023. 10.1073/pnas.1715578115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer R., Gomes-Filho J. V., Randau L. (2021). Conservation of archaeal C/D box sRNA-guided RNA modifications. Front. Microbiol. 12, 654029. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.654029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezicha B., Schmidt M., Makałowska I., Jarmołowski A., Pieńkowska J., Szweykowska-Kulińska Z. (2006). Identification of human tRNA: m5C methyltransferase catalysing intron-dependent m5C formation in the first position of the anticodon of the pre-tRNALeu (CAA) . Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 6034–6043. 10.1093/nar/gkl765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufardeci E., Fabbri S., Baldi M. I., Mattoccia E., Tocchini-Valentini G. P. (1993). In vitro genetic analysis of the structural features of the pre-tRNA required for determination of the 3′ splice site in the intron excision reaction. EMBO J. 12, 4697–4704. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06158.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappannini A., Ray A., Purta E., Mukherjee S., Boccaletto P., Moafinejad S. N., et al. (2024). MODOMICS: a database of RNA modifications and related information. 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D239–D244. 10.1093/nar/gkad1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlile T. M., Rojas-Duran M. F., Zinshteyn B., Shin H., Bartoli K. M., Gilbert W. V. (2014). Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515, 143–146. 10.1038/nature13802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerneckis J., Cui Q., He C., Yi C., Shi Y. (2022). Decoding pseudouridine: an emerging target for therapeutic development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43, 522–535. 10.1016/j.tips.2022.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. T. Y., Pang Y. L. J., Deng W., Babu I. R., Dyavaiah M., Begley T. J., et al. (2012). Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins. Nat. Commun. 3, 937. 10.1038/ncomms1938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. P., Lowe T. M. (2016). GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D184–D189. 10.1093/nar/gkv1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choffat Y., Suter B., Behra R., Kubli E. (1988). Pseudouridine modification in the tRNA(Tyr) anticodon is dependent on the presence, but independent of the size and sequence, of the intron in eucaryotic tRNA(Tyr) genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 3332–3337. 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David R., Burgess A., Parker B., Li J., Pulsford K., Sibbritt T., et al. (2017). Transcriptome-wide mapping of RNA 5-methylcytosine in arabidopsis mRNAs and noncoding RNAs. Plant Cell 29, 445–460. 10.1105/tpc.16.00751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. R. (1995). Stabilization of RNA stacking by pseudouridine. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 5020–5026. 10.1093/nar/23.24.5020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S., Kessler A. C., Henderson J., Pan X., Zhao R., D’Almeida G. S., et al. (2021). Dynamic queuosine changes in tRNA couple nutrient levels to codon choice in Trypanosoma brucei . Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 12986–12999. 10.1093/nar/gkab1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Orval B. C., Bortolin M. L., Gaspin C., Bachellerie J. P. (2001). Box C/D RNA guides for the ribose methylation of archaeal tRNAs. The tRNATrp intron guides the formation of two ribose-methylated nucleosides in the mature tRNATrp. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4518–4529. 10.1093/nar/29.22.4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus C., Barnes D., Alqasem M., Kelly V. (2015). The queuine micronutrient: charting a course from microbe to man. Nutrients 7, 2897–2929. 10.3390/nu7042897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima K., Kanai A. (2014). tRNA gene diversity in the three domains of life. Front. Genet. 5, 142. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S., Rafi M., Aldarmaki M., ElSiddig M., Al Nuaimi M., Amiri K. M. A. (2022). tRNA derived small RNAs—small players with big roles. Front. Genet. 13, 997780. 10.3389/fgene.2022.997780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman H. M., Olson M. V., Hall B. D. (1977). Nucleotide sequence of a mutant eukaryotic gene: the yeast tyrosine-inserting ochre suppressor SUP4-o. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74, 5453–5457. 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean H., Szweykowska-Kulinska Z., Motorin Y., Fasiolo F., Simos G. (1997). Intron-dependent enzymatic formation of modified nucleosides in eukaryotic tRNAs: a review. Biochimie 79, 293–302. 10.1016/S0300-9084(97)83517-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Großhans H., Lecointe F., Grosjean H., Hurt E., Simos G. (2001). Pus1p-dependent tRNA pseudouridinylation becomes essential when tRNA biogenesis is compromised in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46333–46339. 10.1074/jbc.M107141200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzi N., Cieśla M., Ngoc P. C. T., Lang S., Arora S., Dimitriou M., et al. (2018). Pseudouridylation of tRNA-derived fragments steers translational control in stem cells. Cell 173, 1204–1216. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S., Mori S., Suzuki T., Suzuki T., Yoshihisa T. (2019). Impact of intron removal from tRNA genes on Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 5936–5949. 10.1093/nar/gkz270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayne C. K., Butay K. J. U., Stewart Z. D., Krahn J. M., Perera L., Williams J. G., et al. (2023). Structural basis for pre-tRNA recognition and processing by the human tRNA splicing endonuclease complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 824–833. 10.1038/s41594-023-00991-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedűsová E., Kulkarni S., Burgman B., Alfonzo J. D., Paris Z. (2019). The general mRNA exporters Mex67 and Mtr2 play distinct roles in nuclear export of tRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei . Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 8620–8631. 10.1093/NAR/GKZ671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H. (2014). Methylated nucleosides in tRNA and tRNA methyltransferases. Front. Genet. 5, 144. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Jian L., Byström A. S. (2008). A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for formation of the wobble nucleoside 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . RNA 14, 2183–2194. 10.1261/rna.1184108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Johansson M. J. O., Byström A. S. (2005). An early step in wobble uridine tRNA modification requires the Elongator complex. RNA 11, 424–436. 10.1261/rna.7247705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. Q., Motorin Y., Jin Y. X., Grosjean H. (1997). Pleiotropic effects of intron removal on base modification pattern of yeast tRNAPhe: an in vitro study. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2694–2701. 10.1093/nar/25.14.2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joardar A., Gurha P., Skariah G., Gupta R. (2008). Box C/D RNA-guided 2′-O methylations and the intron of tRNATrp are not essential for the viability of Haloferax volcanii . J. Bacteriol. 190, 7308–7313. 10.1128/JB.00820-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. F., Abelson J. (1983). The yeast tRNATyr gene intron is essential for correct modification of its tRNA product. Nature 302, 681–687. 10.1038/302681a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarada L., Suzuki T., Ohira T., Hirata S., Miyauchi K., Suzuki T. (2017). ALKBH1 is an RNA dioxygenase responsible for cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 7401–7415. 10.1093/nar/gkx354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A. C., Kulkarni S. S., Paulines M. J., Rubio M. A. T., Limbach P. A., Paris Z., et al. (2018a). Retrograde nuclear transport from the cytoplasm is required for tRNATyr maturation in T. brucei . RNA Biol. 15, 528–536. 10.1080/15476286.2017.1377878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A. C., Silveira d’Almeida G., Alfonzo J. D. (2018b). The role of intracellular compartmentalization on tRNA processing and modification. RNA Biol. 15, 554–566. 10.1080/15476286.2017.1371402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner S., Ignatova Z. (2015). Emerging roles of tRNA in adaptive translation, signalling dynamics and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 98–112. 10.1038/nrg3861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konevega A. L., Soboleva N. G., Makhno V. I., Semenkov Y. P., Wintermeyer W., Rodnina M. V., et al. (2004). Purine bases at position 37 of tRNA stabilize codon-anticodon interaction in the ribosomal A site by stacking and Mg2+-dependent interactions. RNA 10, 90–101. 10.1261/rna.5142404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutyhołowa R., Zakrzewski K., Glatt S. (2019). Charging the code — tRNA modification complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 55, 138–146. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufel J., Grzechnik P. (2019). Small nucleolar RNAs tell a different tale. Trends Genet. 35, 104–117. 10.1016/j.tig.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S., Rubio M. A. T., Hegedusová E., Ross R. L., Limbach P. A., Alfonzo J. D., et al. (2021). Preferential import of queuosine-modified tRNAs into Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrion is critical for organellar protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 8247–8260. 10.1093/nar/gkab567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesnik C., Golani-Armon A., Arava Y. (2015). Localized translation near the mitochondrial outer membrane: an update. RNA Biol. 12, 801–809. 10.1080/15476286.2015.1058686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. W., Zheng S. Q., Li T., Fei Y. F., Wang C., Zhang S., et al. (2024). RNA modifications in cellular metabolism: implications for metabolism-targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 70. 10.1038/s41392-024-01777-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons S. M., Fay M. M., Ivanov P. (2018). The role of RNA modifications in the regulation of tRNA cleavage. FEBS Lett. 592, 2828–2844. 10.1002/1873-3468.13205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka M. A., Olchowik A., Grosjean H., Bujnicki J. M. (2014). Distribution and frequencies of post-transcriptional modifications in tRNAs. RNA Biol. 11, 1619–1629. 10.4161/15476286.2014.992273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marck C., Grosjean H. (2003). Identification of BHB splicing motifs in intron-containing tRNAs from 18 archaea: evolutionary implications. RNA 9, 1516–1531. 10.1261/rna.5132503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee Y. P., Wu G., Gonzalez-Sulser A., Vaucheret H., Poethig R. S. (2005). Nuclear processing and export of microRNAs in Arabidopsis . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 3691–3696. 10.1073/pnas.0405570102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton D. A., De Robertis E. M., Cortese R. (1980). Order and intracellular location of the events involved in the maturation of a spliced tRNA. Nature 284, 143–148. 10.1038/284143a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty B. K., Kushner S. R. (2019). New insights into the relationship between tRNA processing and polyadenylation in Escherichia coli . Trends Genet. 35, 434–445. 10.1016/j.tig.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort M., Ivanov D., Cooper D. N., Chuzhanova N. A. (2008). A meta-analysis of nonsense mutations causing human genetic disease. Hum. Mutat. 29, 1037–1047. 10.1002/humu.20763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y., Grosjean H. (1999). Multisite-specific tRNA:m5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA 5, 1105–1118. 10.1017/S1355838299982201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y., Keith G., Simon C., Foiret D., Simos G., Hurt E., et al. (1998). The yeast tRNA:pseudouridine synthase Pus1p displays a multisite substrate specificity. RNA 4, 856–869. 10.1017/S1355838298980396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y., Lyko F., Helm M. (2009). 5-methylcytosine in RNA: detection, enzymatic formation and biological functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 1415–1430. 10.1093/nar/gkp1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M., Samel-Pommerencke A., Legrand C., Tuorto F., Lyko F., Ehrenhofer-Murray A. E. (2019). Division of labour: tRNA methylation by the NSun2 tRNA methyltransferases Trm4a and Trm4b in fission yeast. RNA Biol. 16, 249–256. 10.1080/15476286.2019.1568819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A., Kirino Y., Ikeuchi Y., Suzuki T. (2006). Biosynthesis of wybutosine, a hyper-modified nucleoside in eukaryotic phenylalanine tRNA. EMBO J. 25, 2142–2154. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira T., Suzuki T. (2011). Retrograde nuclear import of tRNA precursors is required for modified base biogenesis in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 10502–10507. 10.1073/pnas.1105645108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paushkin S. V., Patel M., Furia B. S., Peltz S. W., Trotta C. R. (2004). Identification of a human endonuclease complex reveals a link between tRNA splicing and pre-mRNA 3′ end formation. Cell 117, 311–321. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00342-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perche-Letuvée P., Molle T., Forouhar F., Mulliez E., Atta M. (2014). Wybutosine biosynthesis: structural and mechanistic overview. RNA Biol. 11, 1508–1518. 10.4161/15476286.2014.992271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phizicky E. M., Hopper A. K. (2023). The life and times of a tRNA. RNA 29, 898–957. 10.1261/rna.079620.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popow J., Schleiffer A., Martinez J. (2012). Diversity and roles of (t)RNA ligases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 2657–2670. 10.1007/s00018-012-0944-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purchal M. K., Eyler D. E., Tardu M., Franco M. K., Korn M. M., Khan T., et al. (2022). Pseudouridine synthase 7 is an opportunistic enzyme that binds and modifies substrates with diverse sequences and structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2109708119. 10.1073/pnas.2109708119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos J., Fu D. (2019). The emerging impact of tRNA modifications in the brain and nervous system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gene Regul. Mech. 1862, 412–428. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold-Hurek B., Shub D. A. (1992). Self-splicing introns in tRNA genes of widely divergent bacteria. Nature 357, 173–176. 10.1038/357173a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintala-Dempsey A. C., Kothe U. (2017). Eukaryotic stand-alone pseudouridine synthases–RNA modifying enzymes and emerging regulators of gene expression? RNA Biol. 14, 1185–1196. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1276150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio M. A. T., Paris Z., Gaston K. W., Fleming I. M. C., Sample P., Trotta C. R., et al. (2013). Unusual noncanonical intron editing is important for tRNA splicing in Trypanosoma brucei . Mol. Cell 52, 184–192. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel P. (2018). The emerging complexity of the tRNA world: mammalian tRNAs beyond protein synthesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 45–58. 10.1038/nrm.2017.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S., Bernstein D. A., Mumbach M. R., Jovanovic M., Herbst R. H., León-Ricardo B. X., et al. (2014). Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159, 148–162. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekulovski S., Trowitzsch S. (2022). Transfer RNA processing-from a structural and disease perspective. Biol. Chem. 403, 749–763. 10.1515/hsz-2021-0406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simos G., Tekotte H., Grosjean H., Segref A., Sharma K., Tollervey D., et al. (1996). Nuclear pore proteins are involved in the biogenesis of functional tRNA. EMBO J. 15, 2270–2284. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00580.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K., Gurha P., Tran E. J., Maxwell E. S., Gupta R. (2004). Sequential 2′-O-methylation of archaeal pre-tRNATrp nucleotides is guided by the intron-encoded but trans-acting box C/D ribonucleoprotein of pre-tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47661–47671. 10.1074/jbc.M408868200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spenkuch F., Motorin Y., Helm M. (2014). Pseudouridine: still mysterious, but never a fake (uridine). RNA Biol. 11, 1540–1554. 10.4161/15476286.2014.992278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel M. C., Abelson J. (1986). Effect of intron mutations on processing and function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SUP53 tRNA in vitro and in vivo . Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 2663–2673. 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara J., Yachie N., Arakawa K., Tomita M. (2007). In silico screening of archaeal tRNA-encoding genes having multiple introns with bulge-helix-bulge splicing motifs. RNA 13, 671–681. 10.1261/rna.309507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T. (2021). The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 375–392. 10.1038/s41580-021-00342-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szweykowska-Kulinska Z., Beier H. (1992). Sequence and structure requirements for the biosynthesis of pseudouridine (Ψ35) in plant pre-tRNATyr . EMBO J. 11, 1907–1912. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05243.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szweykowska-Kulinska Z., Senger B., Keith G., Fasiolo F., Grosjean H. (1994). Intron-dependent formation of pseudouridines in the anticodon of Saccharomyces cerevisiae minor tRNAIle . EMBO J. 13, 4636–4644. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06786.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M., Cech T. (1996). Activity and thermostability of the small self-splicing group I intron in the pre-tRNAlle of the purple bacterium Azoarcus . RNA 2, 74–83. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1369352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebe R., Zachau H. G. (1968). A specific modification next to the anticodon of phenylalanine transfer ribonucleic acid. Eur. J. Biochem. 5, 546–555. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchini-Valentini G. D., Fruscoloni P., Tocchini-Valentini G. P. (2005). Coevolution of tRNA intron motifs and tRNA endonuclease architecture in Archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 15418–15422. 10.1073/pnas.0506750102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchini-Valentini G. D., Fruscoloni P., Tocchini-Valentini G. P. (2009). Processing of multiple-intron-containing pretRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 20246–20251. 10.1073/pnas.0911658106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchini-Valentini G. D., Fruscoloni P., Tocchini-Valentini G. P. (2011). Evolution of introns in the archaeal world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 4782–4787. 10.1073/pnas.1100862108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchini-Valentini G. D., Tocchini-Valentini G. P. (2021). Archaeal tRNA-splicing endonuclease as an effector for RNA recombination and novel trans-splicing pathways in eukaryotes. J. Fungi 7, 1069. 10.3390/jof7121069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta C. R., Miao F., Arn E. A., Stevens S. W., Ho C. K., Rauhut R., et al. (1997). The yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease: a tetrameric enzyme with two active site subunits homologous to the archaeal tRNA endonucleases. Cell 89, 849–858. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80270-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban A., Behm-Ansmant I., Branlant C., Motorlin Y. (2009). RNA sequence and two-dimensional structure features required for efficient substrate modification by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA:Ψ-synthase Pus7p. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5845–5858. 10.1074/jbc.M807986200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tol H., Beier H. (1988). All human tRNATyr genes contain introns as a prerequisite for pseudouridine biosynthesis in the anticodon. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 1951–1966. 10.1093/nar/16.5.1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waas W. F., Druzina Z., Hanan M., Schimmel P. (2007). Role of a tRNA base modification and its precursors in frameshifting in eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26026–26034. 10.1074/jbc.M703391200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Jia Q., Zeng J., Chen R., Xie W. (2017). Structural insight into the methyltransfer mechanism of the bifunctional Trm5. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700195. 10.1126/sciadv.1700195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Xu X., Li X., Fang J., Huang Z., Zhang M., et al. (2023). Investigations of single-subunit tRNA methyltransferases from yeast. J. Fungi 9, 1030. 10.3390/jof9101030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins N. J., Bohnsack M. T. (2012). The box C/D and H/ACA snoRNPs: key players in the modification, processing and the dynamic folding of ribosomal RNA. WIREs RNA 3, 397–414. 10.1002/wrna.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihisa T. (2014). Handling tRNA introns, archaeal way and eukaryotic way. Front. Genet. 5, 213. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihisa T., Ohshima C., Yunoki-Esaki K., Endo T. (2007). Cytoplasmic splicing of tRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genes Cells 12, 285–297. 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihisa T., Yunoki-Esaki K., Ohshima C., Tanaka N., Endo T. (2003). Possibility of cytoplasmic pre-tRNA splicing: the yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease mainly localizes on the mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 3266–3279. 10.1091/mbc.e02-11-0757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerfass K., Beier H. (1992). Pseudouridine in the anticodon GΨA of plant cytoplasmic tRNATyr is required for UAG and UAA suppression in the TMV-specific context. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 5911–5918. 10.1093/nar/20.22.5911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Foo M., Eren A. M., Pan T. (2022). tRNA modification dynamics from individual organisms to metaepitranscriptomics of microbiomes. Mol. Cell 82, 891–906. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Yang F., Zhan X., Bian T., Xing Z., Lu Y., et al. (2023). Structural basis of pre-tRNA intron removal by human tRNA splicing endonuclease. Mol. Cell 83, 1328–1339.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]