Abstract

Objectives

Postmenopausal females often experience genitourinary symptoms like vulvovaginal dryness due to estrogen decline. Hormone replacement therapy is effective in alleviating vaginal atrophy and genitourinary syndrome in this population. Evaluate local estrogen’s safety and effectiveness for alleviating postmenopausal vaginal symptoms, including endometrial thickness, dyspareunia, vaginal pH, and dryness.

Methods

We searched Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, ClinicalTrial.Gov, PubMed, and ScienceDirect databases until July 2023. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) linking intravaginal estrogen supplementation to vaginal atrophy or vaginitis were included. The risk of bias was evaluated with RoB 2, and publication bias was assessed using Egger and Beggs analysis.

Results

All evidence pertains to females. Eighteen studies (n = 4,723) compared estrogen with placebo. Patients using estrogen showed a significant increase in superficial cells (mean differences [MD]: 19.28; 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 13.40 to 25.16; I2 = 90%; P < 0.00001) and a decrease in parabasal cells (MD: −24.85; 95% CI: −32.96 to −16.73; I2 = 92%; P < 0.00001). Vaginal pH and dyspareunia significantly reduced in estrogen users (MD: −0.94; 95% CI: −1.05 to −0.84; I2 = 96%) and (MD: −0.52; 95% CI: −0.63 to −0.41; I2 = 99%), respectively. Estrogen did not significantly affect vaginal dryness (MD: −0.04; 95% CI: −0.18 to 0.11; I2 = 88%). Adverse events like vulvovaginal pruritis, mycotic infection, and urinary tract infection were reported, but the association was insignificant (risk ratio: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.88 to 1.02; I2 = 0%).

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis of 18 RCTs suggests promising potential for intravaginal estrogen therapy in alleviating vaginal atrophy and vaginitis in postmenopausal females.

Keywords: Estradiol, Maturation value, Postmenopausal women, Vaginal atrophy, Vaginal pH

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) refers to various menopausal signs and symptoms including genital symptoms (dryness, burning, and irritation, vulvovaginal atrophy, vaginitis), sexual symptoms (lack of lubrication, discomfort or pain, and impaired function) and urinary symptoms (urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections) [1]. Estrogen-based hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has proven to be effective in treating symptoms of vaginal atrophy and genitourinary syndrome in postmenopausal females [2]. Multiple forms of HRT are available in the market including oral tablets, nasal sprays and local vaginal routes in the form of rings, pessaries, creams, and estrogen-releasing tablets. The cells of the lower genitourinary tract are estrogen sensitive and these medications work directly to relieve symptoms of vaginal atrophy [3]. Local vaginal routes of administration have fewer side effects than systemic routes. Since they do not induce liver metabolism and can be used in lower dosages [4]. The HRT with 40–100 pg/mL of circulating 17β-estrogen level is evaluated to be quite effective in treating genitourinary syndrome symptoms. Although, 10%–25% of females on oral estrogen replacement therapy frequently have genitourinary symptoms [5]. A study by Bachmann et al. [6] estimated that 40%–50% of females complained about vaginal dryness while taking oral hormone therapy. Consequently, the application of low-dose topical estrogen has been advocated as a highly beneficial treatment for females with genitourinary syndrome symptoms [7].

Local treatment for GSM plays a crucial role in addressing its multifaceted symptoms, tailoring interventions to meet the specific needs of affected females. A thorough examination of clinical data underscores the significance of localized approaches. Research highlights the efficacy of local estrogen therapy in mitigating vaginal atrophy and enhancing sexual function among postmenopausal females [8]. Similarly, Simon et al. (2008) [9] contribute to the body of evidence supporting the positive outcomes associated with local estrogen interventions such as vaginal pH, epithelial thickness, and symptoms like dyspareunia and vaginal dryness [10]. Moreover, international guidelines from esteemed organizations such as the International Menopause Society (IMS) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocate for the safety and effectiveness of localized estrogen therapy, encompassing various formulations and intravaginal applications [11,12]. By aligning with evidence-based recommendations derived from these clinical studies and guidelines, healthcare practitioners can offer targeted and individualized local treatments for GSM, promoting improved patient outcomes and enhancing the overall quality of life for postmenopausal females.

The effects of HRT on various health outcomes in females are still under research, previously reported reviews mention low-quality evidence as a limitation [13]. Currently, it becomes imperative to critically evaluate the systematic reviews that play a role in shaping current guidelines and recommendations. This meta-analysis is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2016 [13] which serves as an update to the original 2003 Cochrane review [3]. In the 2016 version, intra-vaginal estrogenic preparations were compared in relieving the symptoms of vaginal atrophy. Our review aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of local estrogen preparations in alleviating postmenopausal vaginal symptoms which included endometrial thickness but also overall symptoms like dyspareunia, vaginal pH and dryness while also reporting significant adverse events. We also included dosage and follow-up subgroups to ensure a comprehensive understanding of these treatments’ effectiveness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources and search strategy

This study was conducted by the established methods recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) and Cochrane guidelines [14,15]. An exhaustive and well-structured literature search was conducted for the included articles across PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, ClinicalTrials.Gov, and ScienceDirect databases. The search range spanned from the inception of each database up to July 2023. The search was executed using carefully selected medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and keywords including “vaginal atrophy” or “vulvovaginal atrophy” “atrophic vaginitis” or “postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis” and “Estradiol” or “estriol” or “E2” or “Estrone” or “E1” or “estetrol” or “E4” or “TX-OO4HR” or “17β-estradiol” and “Placebo” and “Maturation value” or “maturation index” or “dyspareunia” or “vaginal PH” or “vaginal dryness” or: “dryness” or “adverse event” or “urinary tract infection” or “vulvovaginal pruritus:” or “Vulvovaginal mycotic infection”.

The comprehensive search strategy is given in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). Titles, abstracts, full texts, and reference lists of all identified studies were reviewed. The relevant literature references were carefully checked for potentially eligible studies. No restrictions regarding country, race or publication language were set. Reference lists from related main studies and review articles were also checked for additional relevant studies.

Literature inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for eligibility were as follows: (1) Double-arm studies. (2) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included post-menopausal females showing signs of vaginal atrophy or vaginitis. (3) Association of intravaginal estrogen supplementation with vaginal atrophy or vaginitis (4) minimum follow-up for 2 weeks. (5) Females in the postmenopausal stage who had not menstruated in more than a year or who had a serum follicle stimulating hormone level of more than 40 IU/L. (6) Underwent bilateral oophorectomy. (7) All modes of local vaginal application were involved inclusive of vaginal ovules, tablets, and rings. suppositories, vaginal gel and moisturizers. (8) These modes of local vaginal application included variable dose groups of estrogen (9) primary outcomes including maturation value, vaginal PH, dyspareunia and vaginal dryness (10) secondary outcomes included common adverse events: vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection and urinary tract infection.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) Case series, non-human studies, editorials, reviews, abstracts, comments and letters, expert opinions, studies without original data and duplicate publications. (2) Studies lacking a comparison group. (3) Females with serious underlying diseases. (4) Underwent prior hormone treatment within six months of the study’s start date.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two independent researchers (A.I. and M.T.) were tasked with screening the literature based on the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study and patient characteristics including author, year, study design, location, sample size, age, follow-up time, intervention, comparator, common adverse events, maturation value and pH. The potential for prejudice was separately evaluated by two investigators according to the PRISMA guidelines. Any disparities were amicably resolved through conversation or by an independent reviewer (R.I.). The risk of bias was assessed using RoB 2, a revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs. Studies were judged and identified as ‘Low’ or ‘High’ risk of bias or ‘Some concerns’. Publication bias assessment was done using Egger and Beggs analysis.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted utilizing Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4.1, developed by The Cochrane Collaboration in 2020. The analysis incorporated 18 RCTs, focusing on primary outcome measures such as maturation value, vaginal pH, dyspareunia, and vaginal dryness. Additionally, secondary outcomes encompassed adverse events, including vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection, and urinary tract infection.

Primary outcomes of interest were expressed as mean differences (MD) and secondary outcomes of interest included risk ratios (RR). These were presented alongside 95% confidence intervals (CI) and combined using a generic invariance-weighted random-effects model. Visual assessment of the pooled analysis was facilitated through the creation of Forest plots. A subgroup analysis was additionally performed to evaluate the doseresponse relationship of estrogen on outcomes. The included doses were 10 µg, 25 µg, 15 µg, 50 µg, and < 2.5 mg. Examination of heterogeneity across studies was performed using Higgins I2, with emphasis on a threshold of 50% or more for consideration. In instances of elevated observed heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was executed through a leave-one-out approach. Significance in all cases was defined by a P value of < 0.05.

RESULTS

Literature search and quality assessment

The initial literature search identified 80 articles. After a detailed evaluation of these articles according to the inclusion criteria, 18 RCTs were selected for analysis [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], involving a total of 4,723 patients 2,580 in the estrogen group and 1,436 in the placebo group. The mean age of patients was 49 years and they had their follow-ups at a minimum of 2 weeks and a maximum of 24 weeks.

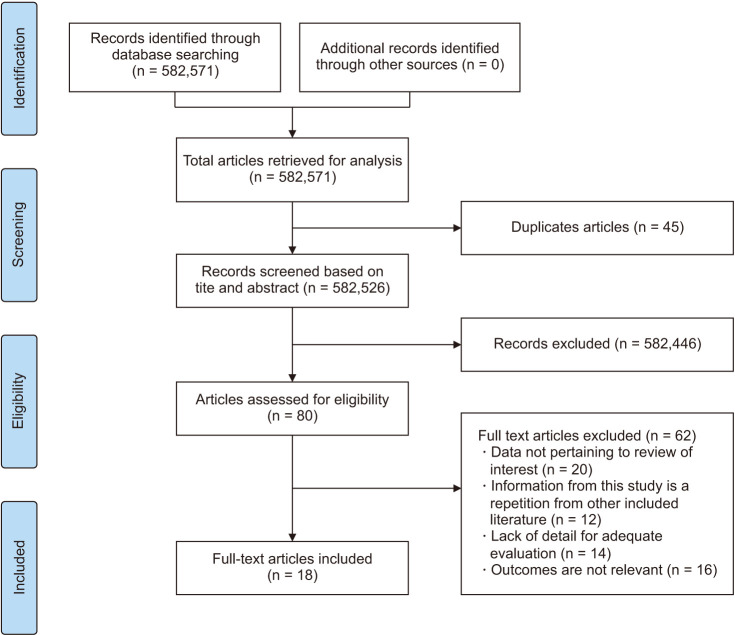

The PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1) summarizes the results of our literature search. Table 1 outlines the baseline characteristics of all included studies. Quality assessment using the Cochrane risk of a bias assessment tool for RCTs demonstrated that 1 study has a low risk of bias, 13 some concerns whereas 4 studies have a high risk of bias (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of included studies.

| Reference | Study design | Location | Sample size | Age (mean ± SD) | Follow up | Intervention | Comparator | Most common adverse event | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | Placebo | Estradiol | Placebo | |||||||

| Archer et al. (2018) [16] | Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study | Estradiol: 287 Placebo: 289 |

59.5 ± 6.7 | 59.8 ± 6.1 | 2, 4, 8, 12 wk | 2, 4, 8, 12 wk | 15 μg estradiol, vaginally | 0.5 g placebo, vaginal cream | Urinarytractinfection (32), vulvovaginalmycoticinfection (18) | |

| Fernandes et al. (2016) [21] | RCT | Brazil | Polyacrylic acid 3 g: 20 Testosterone propionate 300 μg: 20 Conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg: 20 Placebo: 20 |

56.4 ± 4.8 | 57.7 ± 4.7 | 6, 12 wk | 6, 12 wk | Polyacrylic acid 3 g Testosterone propionate 300 μg Conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg, vaginal application for all |

Lubricant with glycerin gel 3 g | Not reported |

| Pickar et al. (2016) [30] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 pilot trial | USA | Estradiol: 24 Placebo: 24 |

62.4 ± 5.7 | 62.6 ± 7.3 | 2 wk | 2 wk | 10 μg TX-004 HR, vaginal capsules | Placebo, vaginal capsules | Vaginal dryness, vaginal irritation, pain when urinating |

| Hirschberg et al. (2020) [26] | Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, international, multicenter study | 5 Spanish sites | Estradiol: 50 Placebo: 11 |

58.9 ± 7.6 | 61.4 ± 4.7 | Weeks 1, 3, 8, and 12 of treatment | Weeks 1, 3, 8, and 12 of treatment | 50 μg estradiol, intravaginal applicator | Moisturizing gel | Breasttenderness, vulvovaginalinflammation, vulvovaginalpruritus, burningsensation, diarrhea, vomiting, mucosaldryness, and pyrexia |

| Kroll et al. (2018) [27] | Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study | Estradiol: 277 Placebo: 271 |

58.7 ± 6.4 | 58.6 ± 6.1 | 2, 4, 8, 12 wk | 2, 4, 8, 12 wk | 15 μg estradiol, vaginal cream | 0.5 g placebo, vaginal cream | ||

| Constantine et al. (2017) [19] | Randomized, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study | 89 sites in the USA and Canada | Estradiol (4 μg): 191 Estradiol (10 μg): 191 Estradiol (25 μg): 190 Placebo: 192 |

4 μg: 59.8 ± 6.0; 10 μg: 58.6 ± 6.3; 25 μg: 58.8 ± 6.2 |

59.4 ± 6.0 | 2, 6, 8, 12 wk | 2, 6, 8, 1wk | 4, 10 or 25 μg estradiol (TX-004HR), vaginal capsule | Matching placebo, same dosage | Headaches, vaginal discharge, nasopharyngitis, and vulvovaginal pruritus, back pain, urinary tract infection, upper respiratory tract infections, oropharyngeal pain |

| Bachmann et al. (2008) [23] | 3-arm parallel RCT. Multi-center, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study | 8 centers in the USA | 25 μg oestradiol tablet (n = 91). 1 tablet inserted into the vagina daily for 14 days, then twice per week 10 μg tablet (n = 92). 1 tablet inserted into the vagina daily for 14 days, then twice per week Placebo (n = 47). 1 tablet inserted into the vaginal daily for 14 days, then twice per week duration: 12 weeks |

25 μg: 58.3 ± 7.4; 10 μg: 57.7 ± 6.5 |

57.6 ± 4.8 | 2, 7, 12 wk | 2, 7, 12 wk | 25 μg oestradiol, vaginal tablet | Placebo, vaginal tablet | N/R |

| Bachmann et al. (2009) [24] | 4-arm parallel RCT. Outpatient, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3b trial | Canada and the USA | Conjugated oestrogen 21/7) (n = 143). 300 μg cream applied once daily (21 days on/7 days off) Placebo (21/7) (n = 72). 300 μg cream applied once daily (21 days on/7 days off) Conjugated oestrogen (2 x/wk) (n = 140). 300 μg cream applied twice weekly Placebo (2 x /wk) (n = 68). 0.3 mg cream applied twice weekly Duration: 12 weeks |

Conjugated estrogen (21/7): 57.7 ± 5.8 Conjugated estrogen (2 x/wk): 57.5 ± 5.5 |

Placebo (21/7): 58.0 ± 5.8 Placebo (2 x/wk): 58.7 ± 5.8 |

4, 6, 12 wk | 4, 6, 12 wk | Conjugated oestrogen 300 μg, vaginal cream | Placebo 300 μg, vaginal cream | Headache, infection |

| Cano et al. (2012) [17] | 2-arm parallel RCT. Prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | 12 centers in Spain | 10 mcg tablet (n = 92). 1 tablet inserted into the vagina daily for 14 days, then twice per week | Estriol gel: 56.5 ± 5.72 | Placebo: 57.2 ± 6.70 | 3, 12 wk | 3, 12 wk | 10 mcg estriol, vaginal tablet | 1 g of placebo vaginal gel | Breast pain, vaginal discharge, vulvovaginal discomfort, application site irritation, genital rash, vulvovaginal pruritus, pruritus, candidiasis, hyperhidrosis, swelling, hot flush, abdominal pain, sensation of leg heaviness |

| Griesser et al. (2012) [25] | A 3-arm, randomized, double-blind study | Germany | Group A: 0.2 mg Estriol (n = 142) Group B: 0.03 mg Estriol (n = 147) Group C: Placebo (n = 147) |

Group A: 64.9 ± 8.1 Group B: 65.4 ± 7.3 |

Group C: 64.8 ± 7.8 | 20 d, 12 wk | 20 d, 12 wk | Group A: 0.2 mg estriol Group B: 0.03 mg estriol, vaginal application |

Placebo | Vulvovaginal burning sensation (7.1%), application site pain (2.8%), vulvovaginal pruritus (2.1%) |

| Casper and Petri (1999) [18] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel design, placebo controlled | 10 clinical sites in Germany | Ring group (n = 33) Placebo group (n = 34) |

> 60 y | > 60 y | 3, 12, 48 wk | 3, 12, 48 wk | 7.5 μg oestradiol, vaginal ring | Placebo | Local vaginal irritation |

| Dessole et al. (2004) [8] | Randomization, double-blind, placebo-controlled | The largest district of northern Sardinia | Oestradiol ovules (n = 44) Placebo vaginal ovules (n = 44) |

58 ± 4 | 56 ± 5 | 24 wk | 24 wk | 1 mg oestradiol, vaginal ovules | Placebo, vaginal ovules Urine loss with | Urine loss with physical exertion, coughing, sneezing and intercourse, and symptoms of genital atrophy conditions, including vaginal dryness and dyspareunia |

| Raghunandan et al. (2010) [31] | India | Estrogen cream: n = 25 Placebo: n = 25 | 52.16 ± 7.53 | 51.60 ± 5.66 | 4, 12 wk | 4, 12 wk | 625 μg equine estrogen, vaginal cream | Nonhormonal lubricant, vaginal gel | Vaginal discharge | |

| Lima et al. (2013) [28] | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinicaltrial | Brazil | Group A: isoflavone glycine (n = 30) Group B: conjugated equine estrogens (n = 25) Group C: placebo (n = 30) |

Group A: isoflavone glycine (n = 57) Group B: conjugated equine estrogens (n = 56) |

Group C: placebo (n = 57) | 4, 12 wk | 4, 12 wk | Group A: isoflavone 4%, vaginally Group B: conjugated equine estrogen 0.3 mg, vaginally |

Placebo, vaginal gel | N/R |

| Gaspard et al. (2023) [22] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase 2 trial | Group A: E4 2.5 mg (n = 52) Group B: E4 5 mg (n = 47) Group C: E4 10 mg (n = 54) Group D: E4 15 mg (n = 49) Group E: placebo (n = 55) |

Group A: 2.5 mg = 54.0 ± 4.4 Group B: 5 mg = 53.8 ± 4.8 Group C: 10 mg = 54.3 ± 4.4 Group D: 15 mg = 55.2 ± 4.0 |

Group E: placebo = 53.7 ± 4.4 | 12 wk | 12 wk | 2.5, 5, 10, or 15 mg, E4, oral |

Placebo, orally | N/R | |

| Delgado et al. (2016) [20] | Randomized trial | Switzerland | 0.002% estriol vaginal gel (20 μg/g; T1): n = 12 0.005% estriol vaginal gel (50 μg/g; T2): n = 13 Ovestinon vaginal cream 0.1% (500 μg/0.5 g; R): n = 12 Vaginal gel matching-placebo: n = 6 |

T1 = 57.4 ± 3.3 T2 = 59.6 ± 4.3 |

R = 57.8 ± 4.4 Placebo = 62.7 ± 6.83 |

22 d | 22 d | T1: 20 μg estriol, vaginal gel T2: 50 μg estriol, vaginal gel R: 500 μg estriol (Ovestinon), vaginal cream |

Placebo | T1: Application site pruritus = 1 T2 Vaginal burning sensation = 1 Application site discomfort = 1 Headache = 1 Dysgeusia = 1 R Application site pruritis = 4 Headache = 1 Abdominal discomfort = 1 Placebo = 0 |

| Simon et al. (2008) [9] | Randomized trial | USA, Canada | Vaginal E2 tablet: n = 205 Placebo: n = 104 |

57.5 ± 5.64 | 57.7 ± 5.27 | 2, 4, 8, 12, 52 wk | 2, 4, 8, 12, 52 wk | 10 μg E2 vaginal estradiol tablet | Placebo | Headaches and vaginal discharge among placebo-treated participants Vulvovaginal mycotic infection, back pain, and vulvovaginal Pruritus were more frequent among participants treated with 10 μg E2 |

| Mitchell et al. (2018) [29] | Randomized trial | USA | Vaginal estradiol: n = 102 Dual placebo: n = 100 |

61 ± 4 | 61 ± 4 | 4, 12 wk | 4, 12 wk | 10 μg vaginal estradiol tablet | Placebo tablet | Increased vaginal secretions, vaginal itching, breast tenderness, vaginal spotting or bleeding, vulvovaginal rash, body rash |

SD: standard deviation, g: gram, mg: milligram, µg/mcg: microgram, n: sample size, x: times, T1/T2/R: estriol gel formulations, E2/E4: vaginal tablets, RCT: randomized controlled trial, N/R: not reported.

Maturation value

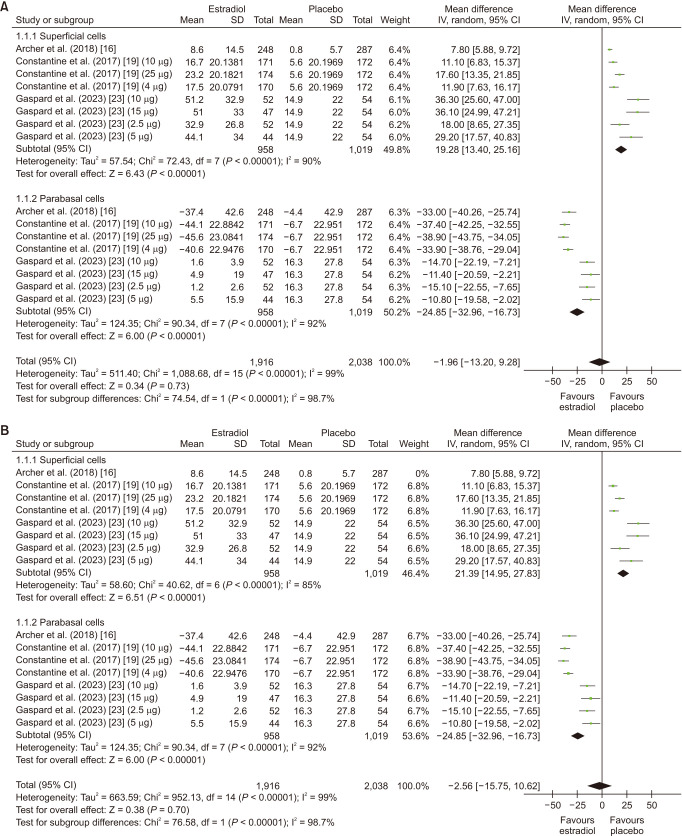

The analysis included 3 studies [16,19,22]. The overall mean maturation value was non significant in patients taking estrogen (MD: −1.96; 95% CI: −13.20 to 9.28; I2 = 99%; P = 0.73). However, upon conducting a subgroup analysis, it revealed an increase in superficial cells (MD: 19.28; 95% CI: 13.40 to 25.16; I2 = 90%; P < 0.00001), whereas it showed a decrease in parabasal cells (MD: −24.85; 95% CI: −32.96 to −16.73; I2 = 92%; P < 0.00001) (Fig. 2A). Leave one out sensitivity analysis did not result in a significant reduction in heterogeneity (Fig. 2B). There was no evidence of significant publication bias with Begg’s test (P value = 0.29627) and with Egger’s test (P value = 0.06862) (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

Fig. 2. (A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for maturation value in superficial cells and parabasal cells in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estrogen vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for maturation value in superficial cells and parabasal cells in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estrogen vs. placebo. CI: confidence intervals, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

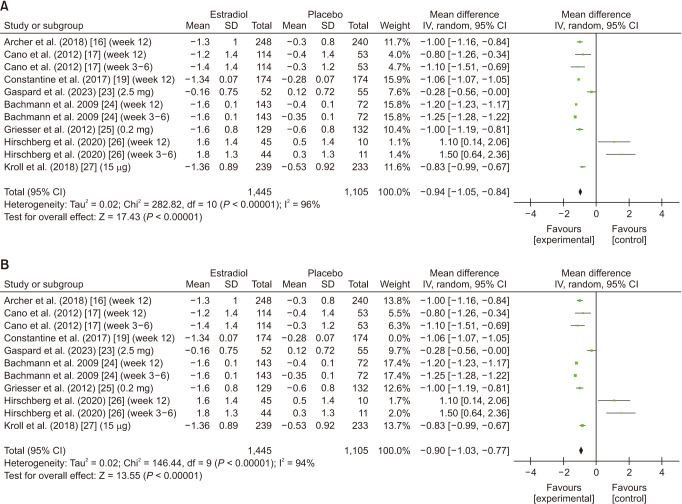

Vaginal pH

The analysis included 8 studies [16,17,19,22,24,25,26,27]. Patients using estrogen had a significant reduction in the average change in vaginal pH (MD: −0.94; 95% CI: −1.05 to −0.84; I2 = 96%; P < 0.00001) (Fig. 3A). Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis of Constantine et al. [19] had a slight influence on the heterogeneity while the results remained significant (MD: −0.90; 95% CI: −1.03 to −0.77; I2 = 94%; P < 0.00001) (Fig. 3B). Upon conducting subgroup analysis for follow-up duration, estrogen’s effect on vaginal pH was significant for the overall follow-up (MD: −1.01; 95% CI: −1.12 to −0.90; I2 = 97%; P < 0.00001). However insignificant subgroup differences (P = 0.24) were revealed between the 3–6 week and 12-week follow-up. The results were significant for the subgroup week 12 follow-up (MD: −1.00; 95% CI: −1.12 to −0.88; I2 = 95%; P < 0.00001) (Supplementary Fig. 2A, available online). Upon leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, significant changes in heterogeneity were not yielded (Supplementary Fig. 2B, available online).

Fig. 3. (A) Summarized Forest plot displaying analysis for vaginal pH in patients with vaginal atrophy patients receiving estrogen vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for vaginal pH in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estrogen vs. placebo. CI: confidence intervals, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

In the dose-response analysis, three subgroups were included: < 2.5 µg, 15 µg, and 50 µg. Although the overall effect was significant (MD: −0.68; 95% CI: −0.96 to −0.40), insignificant subgroup differences were revealed between the aforementioned subgroups (P = 0.44). Females taking a 15 µg dosage of estrogen shown to have a significant reduction in vaginal pH (MD: −0.92; 95% CI: −1.08 to −0.75; I2 = 53%; P < 0.00001) while those taking the 50 µg dosage (MD: 0.10; 95% CI: −1.76 to 1.96; I2 = 92%; P = 0.92) and < 2.5 µg dosage had an insignificant effect on lowering vaginal pH (MD: 0.10; 95% CI: −1.76 to 1.96; I2 = 92%; P = 0.92) and (MD: −0.65; 95% CI: −1.35 to 0.06; I2 = 94%; P = 0.07) respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3, available online). There was no evidence of significant publication bias with Begg’s test (P value = 0.90154) and with Egger’s test (P value = 0.08658) (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

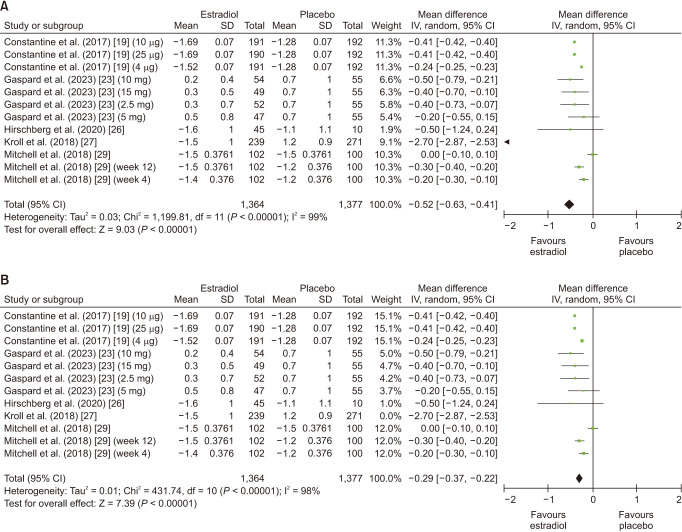

Dyspareunia

Overall, 5 number of studies were included in this analysis [19,22,26,27,29]. Dyspareunia was significantly reduced in patients taking estrogen (MD: −0.52; 95% CI: −0.63 to −0.41; I2 = 99%; P < 0.00001) (Fig. 4A). Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis did not lead to a significant reduction in heterogeneity while the results remained significant (Fig. 4B). Upon conducting subgroup analysis for follow-up duration, estrogen had an overall significant effect on dyspareunia (MD: −0.28; 95% CI: −0.35 to −0.20; I2 = 98%; P < 0.00001), however the subgroup differences between weeks 3–4 and week 12 were insignificant (P = 0.24). However, a significant effect in the subgroup week 12 follow-up (MD: −0.31; 95% CI: −0.39 to −0.28; I2 = 98%; P < 0.00001) was revealed (Supplementary Fig. 4A, available online). Leave one out sensitivity analysis did not reveal any significant changes (Supplementary Fig. 4B, available online). There was evidence of no significant publication bias with Begg’s test (P value = 0.80650) and with Egger’s test (P value = 0.86523) (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

Fig. 4. (A) Summarized Forest plot displaying analysis for dyspareunia in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estrogen vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for dyspareunia in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estrogen vs. placebo. CI: confidence intervals, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

Vaginal dryness

Overall, 4 number of studies were included in this analysis [16,26,27,29]. Estrogen did not have a significant effect on vaginal dryness (MD: −0.04; 95% CI: −0.18 to 0.11; I2 = 88%; P = 0.60) (Supplementary Fig. 5A, available online). In a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, Kroll et al. [27] demonstrated some effect on heterogeneity, while the results remained insignificant (MD: 0.03; 95% CI: −0.07 to 0.13; I2 = 75%; P = 0.57) (Supplementary Fig. 5B, available online). There was evidence of no significant publication bias with Begg’s test (P value = 0.73410) and with Egger’s test (P value = 0.26293) (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

Adverse events

The analysis included 11 studies [16,17,19,20,21,24,25,26,27,30,31]. Initially, the association between estrogen use and adverse events was found to be insignificant (RR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.88 to 1.02; I2 = 0%; P = 0.17) (Supplementary Fig. 6A, available online). However, upon conducting leave one out sensitivity analysis, removing Simon et al. [9], led to significant results with unaltered heterogeneity (RR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.82 to 0.99; I2 = 0%; P = 0.04) (Supplementary Fig. 6B, available online). Additionally, significant subgroup differences (P = 0.003) were revealed upon subgroup analysis of common adverse events including vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection and urinary tract infection. The most common adverse events were vulvovaginal mycotic infection (RR: 2.82; 95% CI: 1.23 to 6.46; I2 = 30%; P = 0.01) followed by vulvovaginal pruritis (RR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.31 to 0.89; I2 = 0%; P = 0.02). Some studies also reported urinary tract infection as a common adverse event but it was found to be insignificant (RR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.85; I2 = 0%; P = 0.62) (Supplementary Fig. 7A, available online). Sensitivity analysis was done by removing Cano et al. [17] which had minimum impact heterogeneity (Supplementary Fig. 7B, available online). There was evidence of no significant publication bias with Begg’s test (P value > 0.999) and with Egger’s test (P value = 0.18319) (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study conducted to date including a total of 18 RCTs with 4,723 patients. The meta-analysis focused on estrogen-based interventions administered intra-vaginally for a minimum period of three months in post-menopausal females to alleviate symptoms arising from vaginal atrophy or vaginitis. The included trials explored the contrast between the intervention (intravaginal estrogen supplementation) and a control group (placebo), using various forms such as creams, gels, tablets, triumphs, ovules, pessaries, and a ring that releases estrogen. Our meta-analysis revealed a reduction in maturation value, dyspareunia and vaginal pH. Upon dose-response analysis, females taking 15 µg of estrogen were shown to have a significant reduction in vaginal pH while those taking the < 2.5 µg and 50 µg had an insignificant effect on lowering vaginal pH. Upon subgroup analysis of follow-up duration, a significant association was observed in the 12-week follow-up for vaginal pH and dyspareunia. Lastly, the most common adverse events were vulvovaginal mycotic infection followed by vulvovaginal pruritis. These comprehensive findings contribute valuable insights into the multifaceted role of estrogen in managing vaginal health and associated symptoms within a scientific research context.

In our study, we assessed the vaginal maturation index (VMI) through the examination of the proportion of superficial and parabasal cells. This method serves to identify vaginal atrophy and estrogen deficiency in postmenopausal females experiencing symptoms [32]. Our findings demonstrated a notable increase in superficial cells, accompanied by a significant decrease in parabasal cells. The reason behind this can be attributed to the role of estrogen, an estrogen-responsive molecule, in activating genes that facilitate the growth and maturation of vaginal cells, particularly superficial cells [33]. Conversely, less mature parabasal cells decrease in number as they differentiate into intermediate and superficial cells. This transformation enhances vaginal health and alleviates symptoms of vaginal atrophy. Variations in the distribution and regulation of estrogen receptors among individuals influence the effectiveness of estrogen therapy. The overall reduction in VMI resulting from estrogen may be attributed to the limited number of studies reporting VMI as an outcome (specifically, three RCTs) or the application of different forms of estrogen across various studies.

Low estrogen levels in postmenopausal females are associated with an increase in the acidic vaginal pH [19]. One of how estrogen mediates its effect is through an increase in proton secretion from vaginal epithelial cells [20]. Estrogen may also increase vaginal glycogen content allowing increased metabolic activity of lactobacillus which leads to lactic acid production and decreased pH [8]. Low vaginal pH prevents colonization with bacteria and subsequent infection so lowering vaginal pH in postmenopausal females is of much clinical importance [21]. Our meta-analysis showed a significant decrease in vaginal pH with estrogen use overall. The exception to this was the 3–6 week follow-up subgroup, which could be explained by limited follow-up duration as follow-up at 12 weeks showed significant improvement in pH. This indicates estrogen should be used for at least 12 weeks to see discernible outcomes. Our meta-analysis also provides valuable information on effective estrogen dosage. The 15 µg dosage showed significant pH improvement and may be considered the optimum dosage for most patients. A dosage of 50 µg and 2.5 µg may not exhibit the same level of efficacy and are less preferable.

Our meta-analysis has demonstrated that the use of estrogen significantly reduces dyspareunia, except for a subgroup that was followed up for 3–4 weeks, which is likely due to the short duration of the follow-up. It should be noted that a significant improvement in dyspareunia is observed after 12 weeks of usage, implying that estrogen should be administered for a minimum of 12 weeks to achieve noticeable benefits. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) and dryness are prevalent indications of the decrease in the internal yield of estrogen during menopause and often lead to dyspareunia [34]. Dyspareunia is characterized as consistent, repetitive urogenital agony happening before, during, or after sexual intercourse and about 40% of females with vaginal atrophy report dyspareunia [35]. Estrogen assumes a crucial part in upholding vaginal moisture, preserving the thickness of the vaginal wall, and maintaining tissue flexibility. However, as a result of decreased estrogen production, it may lead to a reduction in the thickness of the vaginal lining, a decrease in elasticity, and a decline in lubrication, which could potentially make it more fragile and susceptible to irritation and injury during sexual activity, thereby causing dyspareunia.

Dryness is one of the most bothersome symptoms of GSM which has significant negative effects on patients’ sexual experience [36]. Our meta-analysis showed an insignificant effect of vaginal estrogen on vaginal dryness even when stratified by dosage (10–15 µg) and follow-up (at weeks 3–4). This may be attributed to the relatively small number of studies reporting dryness as an outcome (4 RCTs). This may also be due to differing forms of application among the studies: vaginal cream (Kroll et al. [27] and Archer et al. [16], vaginal gel (Hirschberg et al. [26]) and vaginal tablet (Mitchell et al. [29]) leading to inconsistent outcomes. One of the four studies, Hirschberg et al. [26], was conducted on subjects concurrently receiving aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer. Aromatase inhibitors lead to depressed blood estrogen levels which may mask the effect of vaginal estrogen administration. This suggests that while estrogen therapy excels in alleviating specific symptoms, its impact on vaginal dryness may be less pronounced and may require individualized approaches. In the 16 weeks of follow-up (including the visit after treatment), there were no deaths or major adverse reactions related to the treatment observed. Only a few trivial side effects were taken into account, like breast tenderness, vaginal inflammation, itching, burning, diarrhoea, nausea, dry mouth, and fever, but each of these only happened once in six breast cancer patients who got the active treatment.

The meta-analysis investigated the link between estrogen usage and adverse events. Initially, the data did not show a significant connection, suggesting that estrogen had minimal to no effect on overall adverse events. However, when we performed a sensitivity analysis and excluded the studies conducted by Simon et al. and Cano et al. [9,17], the results became statistically significant. Simon et al. [9] reported endometrial adenocarcinoma as the most severe adverse event in one of their study participants. While it is undeniable that the medication had an impact on this condition, it’s crucial to take into account the limited scope of this study, which makes it improbable that the medication was the sole cause of the problem. The study also does not provide information on several other individual events that are covered in our meta-analysis. On the other hand, Cano et al. [17] discussed that most of the adverse events were not linked to the study medication, which may have contributed to the lack of significant results before the sensitivity analysis. Our results indicated that the most commonly observed significant adverse event associated with the treatment was vulvovaginal mycotic infections, leading to vulvovaginal itching. This is attributed to the role of estrogen in reducing vaginal pH, which disrupts the natural vaginal biome and makes it more susceptible to infections, particularly by organisms such as candida. Urinary tract infections were considered a noteworthy and frequent adverse event, but they did not demonstrate any significant association upon analysis. This suggests that while estrogen therapy excels in alleviating specific symptoms, its impact on vaginal dryness may be less pronounced and may require individualized approaches.

Limitations

When interpreting the findings of this meta-analysis, certain factors should be kept in mind because they may pose limitations. The first is that there are different definitions and methods of obtaining baseline values for the maturation index and pH being used. Studies reveal a variety of ranges for these outcomes. Another limitation can be the limited number of studies for certain outcomes; for instance, out of the 18 studies included, less than half report dysuria as a primary or a secondary outcome. The lack of ethnic and geographic diversity, with Asians being the least studied population, might also be seen as a potential limitation in this case. Our review aimed to include every available intervention of estrogen regardless of the mode of administration, type or dosage. This gave us a large sample size, as we covered various forms of estrogen. However, this also limited our ability to compare the effectiveness of different modes or doses of estrogen.

Few studies were ambiguous when discussing adverse events and did not include certain individual adverse events that we compared in our analysis. For example, Cano et al. [17] discuss vulvovaginal pruritus as the most commonly reported adverse event in their study but Bachmann et al. [24] do not mention any adverse events of this nature. Disparity in this regard might lead to differences in the overall interpretation of results. While our study aims to compare the effects of estrogen on VVA symptoms, the lack of recently updated articles in the databases all over Cochrane, PubMed and Google Scholar also limits the pool of RCTs that we can select for our analysis. Therefore, we believe that further studies should consider using multivariable analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of various routes of administration in addition to their ability to affect VVA and endometrial adverse events generally.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that intravaginal estrogen therapy, as evaluated in our comprehensive meta-analysis of 18 RCTs, holds significant promise for post-menopausal females with vaginal atrophy and vaginitis. The significant reduction in maturation value, characterized by an increase in superficial cells and a decrease in parabasal cells, suggests that estrogen contributes to improved vaginal health by fostering a more youthful and resilient vaginal epithelium. It effectively lowers vaginal pH, reduces dyspareunia, and improves maturation value. While its impact on vaginal dryness may be less pronounced, the overall safety profile of estrogen therapy is favourable, with manageable adverse events. These insights empower healthcare providers to tailor treatment plans, offering effective relief and improving the quality of life for post-menopausal females dealing with these challenging symptoms.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING: No funding to declare.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Comprehensive search strategy with MeSH terms

Egger’s and Begg’s test table

Summary of the quality assessment of the included trials.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for Vaginal pH at follow-up weeks 3–6 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for Vaginal pH at follow-up weeks 3–6 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for Vaginal pH at receiving dosage < 2.5, 15 or 50 ug in patients with Vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for dyspareunia at follow-up weeks 3–4 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for dyspareunia in follow-up weeks 3–4 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying analysis for Vaginal dryness in patients with Vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying Sensitivity analysis for Vaginal dryness in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV, inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying analysis for overall adverse events in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for Overall Adverse Events in patients with vaginal atrophy patients receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, IV: inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for adverse events including vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection and urinary tract infection in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for adverse events including vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection and urinary tract infection in patients with vaginal atrophy patients receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, IV: inverse variance.

References

- 1.Kim HK, Kang SY, Chung YJ, Kim JH, Kim MR. The recent review of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. J Menopausal Med. 2015;21:65–71. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2015.21.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S, Whitehead M. Oestrogen therapy and the menopausal syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1977;4:31–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001500. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heimer G, Englund D. Estriol: absorption after long-term vaginal treatment and gastrointestinal absorption as influenced by a meal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63:563–567. doi: 10.3109/00016348409156720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RN, Studd JW. Recent advances in hormone replacement therapy. Br J Hosp Med. 1993;49:799–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachmann GA, Notelovitz M, Kelly SJ, Owens A, Thompson C. Long term nonhormonal treatment of vaginal dryness. Clin Pract Sex. 1992;8:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardozo L, Bachmann G, McClish D, Fonda D, Birgerson L. Meta-analysis of estrogen therapy in the management of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women: second report of the Hormones and Urogenital Therapy Committee. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:722–727. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dessole S, Rubattu G, Ambrosini G, Gallo O, Capobianco G, Cherchi PL, et al. Efficacy of low-dose intravaginal estriol on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2004;11:49–56. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000077620.13164.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon J, Nachtigall L, Gut R, Lang E, Archer DF, Utian W. Effective treatment of vaginal atrophy with an ultra-low-dose estradiol vaginal tablet. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1053–1060. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818aa7c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derzko CM, Röhrich S, Panay N. Does age at the start of treatment for vaginal atrophy predict response to vaginal estrogen therapy? Post hoc analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial involving 205 women treated with 10 μg estradiol vaginal tablets. Menopause. 2020;28:113–118. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AWHONN Lifelines. ACOG issues hormone therapy guidelines. Experts expand estrogen advice; renounce herbs for hot flashes. AWHONN Lifelines. 2005;9:39–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6356.2005.tb00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A IMS Writing Group. 2016 IMS recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2016;19:109–150. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1129166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lethaby A, Ayeleke RO, Roberts H. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD001500. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer DF, Kimble TD, Lin FDY, Battucci S, Sniukiene V, Liu JH. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of estradiol vaginal cream 0.003% in postmenopausal women with vaginal dryness as the most bothersome symptom. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:231–237. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cano A, Estévez J, Usandizaga R, Gallo JL, Guinot M, Delgado JL, et al. The therapeutic effect of a new ultra low concentration estriol gel formulation (0.005% estriol vaginal gel) on symptoms and signs of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: results from a pivotal phase III study. Menopause. 2012;19:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182518e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casper F, Petri E. Local treatment of urogenital atrophy with an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring: a comparative and a placebo-controlled multicenter study. Vaginal Ring Study Group. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s001920050040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constantine GD, Simon JA, Pickar JH, Archer DF, Kushner H, Bernick B, et al. REJOICE Study Group. The REJOICE trial: a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of a novel vaginal estradiol soft-gel capsule for symptomatic vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2017;24:409–416. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delgado JL, Estevez J, Radicioni M, Loprete L, Moscoso Del Prado J, Nieto Magro C. Pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of two vaginal gel formulations of ultra-low-dose estriol in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19:172–180. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1098609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandes T, Costa-Paiva LH, Pedro AO, Baccaro LF, Pinto-Neto AM. Efficacy of vaginally applied estrogen, testosterone, or polyacrylic acid on vaginal atrophy: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2016;23:792–798. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaspard U, Taziaux M, Jost M, Coelingh Bennink HJT, Utian WH, Lobo RA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study to select the minimum effective dose of estetrol in postmenopausal participants (E4Relief): part 2-vaginal cytology, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and health-related quality of life. Menopause. 2023;30:480–489. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bachmann G, Lobo RA, Gut R, Nachtigall L, Notelovitz M. Efficacy of low-dose estradiol vaginal tablets in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:67–76. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296714.12226.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachmann G, Bouchard C, Hoppe D, Ranganath R, Altomare C, Vieweg A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose regimens of conjugated estrogens cream administered vaginally. Menopause. 2009;16:719–727. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a48c4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griesser H, Skonietzki S, Fischer T, Fielder K, Suesskind M. Low dose estriol pessaries for the treatment of vaginal atrophy: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy of pessaries containing 0.2mg and 0.03mg estriol. Maturitas. 2012;71:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschberg AL, Sánchez-Rovira P, Presa-Lorite J, Campos-Delgado M, Gil-Gil M, Lidbrink E, et al. Efficacy and safety of ultra-low dose 0.005% estriol vaginal gel for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer treated with nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause. 2020;27:526–534. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroll R, Archer DF, Lin Y, Sniukiene V, Liu JH. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of estradiol vaginal cream 0.003% in postmenopausal women with dyspareunia as the most bothersome symptom. Menopause. 2018;25:133–138. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima SM, Yamada SS, Reis BF, Postigo S, Galvão da Silva MA, Aoki T. Effective treatment of vaginal atrophy with isoflavone vaginal gel. Maturitas. 2013;74:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, Larson JC, Newton KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Efficacy of vaginal estradiol or vaginal moisturizer vs placebo for treating postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:681–690. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickar JH, Amadio JM, Hill JM, Bernick BA, Mirkin S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 pilot trial evaluating a novel, vaginal softgel capsule containing solubilized estradiol. Menopause. 2016;23:506–510. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raghunandan C, Agrawal S, Dubey P, Choudhury M, Jain A. A comparative study of the effects of local estrogen with or without local testosterone on vulvovaginal and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1284–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bleibel B, Nguyen H. Vaginal atrophy. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu XL, Huang ZY, Yu K, Li J, Fu XW, Deng SL. Estrogen biosynthesis and signal transduction in ovarian disease. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:827032. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.827032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kingsberg S, Kellogg S, Krychman M. Treating dyspareunia caused by vaginal atrophy: a review of treatment options using vaginal estrogen therapy. Int J Womens Health. 2010;1:105–111. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North American Menopause Society. The role of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: 2007 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14:355–369. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31805170eb. quiz 370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon JA, Nappi RE, Kingsberg SA, Maamari R, Brown V. Clarifying vaginal atrophy’s impact on sex and relationships (CLOSER) survey: emotional and physical impact of vaginal discomfort on North American postmenopausal women and their partners. Menopause. 2014;21:137–142. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318295236f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comprehensive search strategy with MeSH terms

Egger’s and Begg’s test table

Summary of the quality assessment of the included trials.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for Vaginal pH at follow-up weeks 3–6 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for Vaginal pH at follow-up weeks 3–6 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for Vaginal pH at receiving dosage < 2.5, 15 or 50 ug in patients with Vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for dyspareunia at follow-up weeks 3–4 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for dyspareunia in follow-up weeks 3–4 or 12 in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV: inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying analysis for Vaginal dryness in patients with Vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying Sensitivity analysis for Vaginal dryness in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, SD: standard deviations, IV, inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying analysis for overall adverse events in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for Overall Adverse Events in patients with vaginal atrophy patients receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, IV: inverse variance.

(A) Summarized Forest plot displaying subgroup analysis for adverse events including vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection and urinary tract infection in patients with vaginal atrophy receiving estradiol vs. placebo. (B) Summarized Forest plot displaying sensitivity analysis for adverse events including vulvovaginal pruritis, vulvovaginal mycotic infection and urinary tract infection in patients with vaginal atrophy patients receiving estradiol vs. placebo. Cl: confidence interval, IV: inverse variance.