Abstract

Study Design: Cross-sectional study.

Objective: The prevalence and etiology of facial fractures differ in each country. The aim of this study was to determine the patterns, trauma mechanism, and treatment of midface and mandible fractures in a government hospital in Mexico City.

Methods: A three-year cross-sectional study was done at Balbuena General Hospital in Mexico City. The variables of interest were age, gender, place of origin, fracture site, trauma mechanism, and treatment. Between 2016 and 2019, physical and electronic data records of patients that exhibited facial fractures were included. Statistical analyses performed included descriptive analysis and a chi-square test.

Results: A total of 490 cases of fractures in the maxillofacial region were reviewed, of which 237 (47%) cases presented fractures in the midface. A higher male ratio (M: F 12:1) was observed. The age range varied between 18 and 80 years, with a mean of 35.58 ± 14 years. The most frequent diagnosis was a zygomatic complex fracture, 37.97%. (n = 90). The most frequent trauma mechanism was interpersonal violence at 55.93% (n = 132) in both places of origin (P = .06). Conservative treatment was more frequent at 71.67% in intrapersonal violence (P = .019). Interpersonal violence was more frequent in males at 61.64%, and motor vehicle accident was more frequent in female at 61.11% (P = .028).

Conclusions: The analysis provides information that can help to focus preventive measures regarding facial fractures, especially on efforts to reduce interpersonal violence.

Keywords: maxillofacial trauma, facial fractures, facial pattern fractures, epidemiology, midface fracture, mandible fracture

Introduction

Maxillofacial fractures are currently one of the most frequent pathologies in emergency

Oral and maxillofacial surgical services.1,2 The statistics are different due to variations in socioeconomic, lifestyle, legislative, environmental, and cultural factors. 3 Recent studies report an increase in cases of maxillofacial trauma; this sends a significant national public health problem that requires alternative solutions in the short, medium, and long term.1,4 Facial fractures could originate permanent damage such as scarring, facial asymmetry, and poor facial aesthetics, resulting in emotional and psychological impacts.4,5 Post-traumatic stress syndrome and depression are common after facial injuries. 5

Maxillofacial injuries are also associated with a high government cost due to the hospital resources used for treatment and time lost due to the work incapacity of the patients.1,2 The epidemiology of these injuries varies according to the type of fracture, severity, cause, and population studied. Hence, there is significant variability in the results of the studies, which show that the damage in the facial area is mainly caused by traffic accidents,6,7 interpersonal violence,3,8,9 sports, 10 and falls. 11 Worldwide, there is a higher prevalence of fractures due to traffic accidents. However, there is a higher proportion of traumas related to interpersonal violence in the lower socioeconomic areas.3,9

This study aims to determine the patterns, trauma mechanism, and treatment of facial fractures at Balbuena General Hospital in Mexico in 3 years. A review of current trends is essential to guide the management and allocate government resources to prevent and treat maxillofacial fractures.

Materials and Methods

A three-year cross-sectional study was done at Balbuena General Hospital in Mexico City. The data of all the physical and electronic records of patients with trauma at the maxillofacial level between January 1, 2016, and February 28, 2019, were recorded. Patients were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnostic codes for maxillofacial trauma. Inclusion criteria were (1) Medical records associated with (ICD-10 10th Revision) codes S02.2–S02.9; (2) patients over 16 years old; (3) present informed consent of the treatment, and (4) medical records with a complete imaging file confirming the diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were (1) records that did not have a CT scan, (2) that had an incomplete medical history, (3) isolated soft tissue injuries, and (3) isolated dental/dentoalveolar injuries. Medical records were reviewed to record age, gender, place of residence (urban or rural), fracture location, trauma mechanism, and treatment (open reduction and internal fixation–closed treatment). Fractures were divided into mandibular fractures (symphysis/parasymphysis, body, angle/ramus, condylar process and head, and coronoid) and maxillary fractures (palatoalveolar, zygomatic complex, Le Fort I, Le Fort II, Le Fort III, nasal, and orbital). Patients were classified based on trauma mechanisms such as road traffic accidents, falls, interpersonal violence, and a gunshot wound.

The data were collected in single data forms using EpiData® (version 4.6.0.4). They were tabulated on a computer. Analysis was performed using STATA® MP (version 14) and determined the statistical significance level at .05. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies, and quantitative variables as means and standard deviation. As appropriate, comparisons were performed with chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and Mann–Whitney’s U tests.

Results

From 2018 to 2020, a total of 490 cases of midface and mandibular fractures were reviewed, of which 237 (47%) patients presented fracture in the midface and 253 (53%) cases in the mandible.

Age Distribution of Fractures

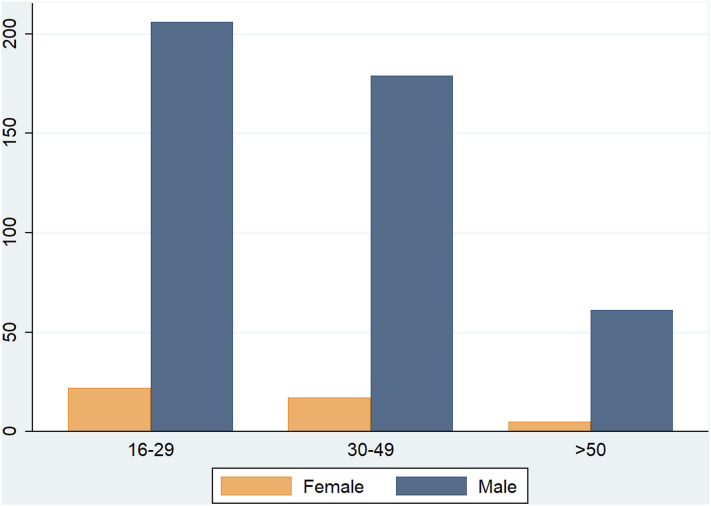

The age of the patients ranged from 15 to 80 years, with a mean age of 33.6 ± 13.1 and a median of 35. Of all patients, 46.5% were 16–29 years, 40% were 30–49 years, and 30.5% were older than 50 years old, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Age group and gender distribution in 490 midface and mandibular fractures cases.

A stratification of trauma mechanism according to age showed that in the 30–49 years group, interpersonal violence was more frequent at 46%, and in the 16–29 years group, traffic accidents were more frequent at 68%, as seen in Table 1. This distribution of fractures is statistically significant (P = .007).

Table 1.

Distribution of facial fractures in midface and mandible.

| Variable | Midface (%) n = 237 | Mandible (%) n = 253 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .299 | ||

| Female | 18 (7.6) | 26 (10.3) | |

| Male | 219 (92.4) | 227 (89.7) | |

| Age group | .007* | ||

| 16-29 | 95 (40.0) | 133 (52.6) | |

| 30-49 | 101 (42.6) | 95 (37.6) | |

| >50 | 41 (17.3) | 25 (9.9) | |

| Place of residence | <.001* | ||

| Urban | 147 (62.0) | 194 (76.7) | |

| Rural | 90 (38.0) | 59 (23.3) | |

| Trauma mechanism | <.001* | ||

| Interpersonal violence | 140 (50.0) | 188 (74.3) | |

| Road traffic | 73 (30.8) | 37 (14.6) | |

| Fall | 14 (5.9) | 24 (9.5) | |

| Gunshot wound | 10 (4.2) | 4 (1.6) |

Chi2 *P < .05.

Gender Distribution

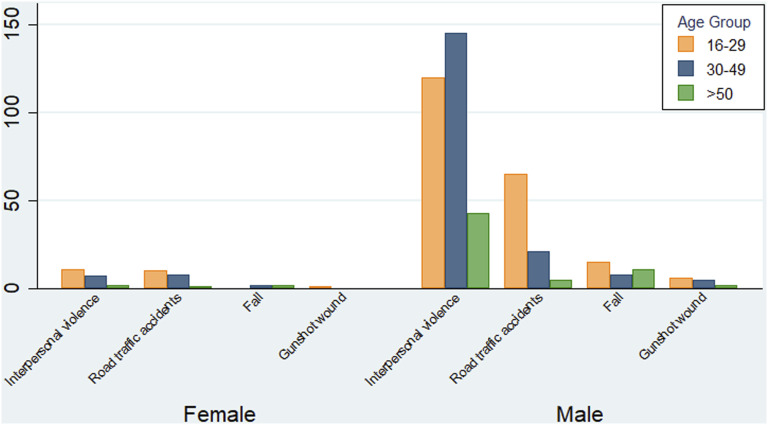

A higher male ratio (M: F 10:1) was observed. There was a difference in the distribution in gender, etiology, and age groups, as seen in Figure 2. Interpersonal violence was more frequent in the 30–49 age male group and the 16–29 age female group (P = .299).

Figure 2.

Frequency of facial fracture patterns by age group in females and males in 490 midface and mandibular fractures cases.

Place of Residence

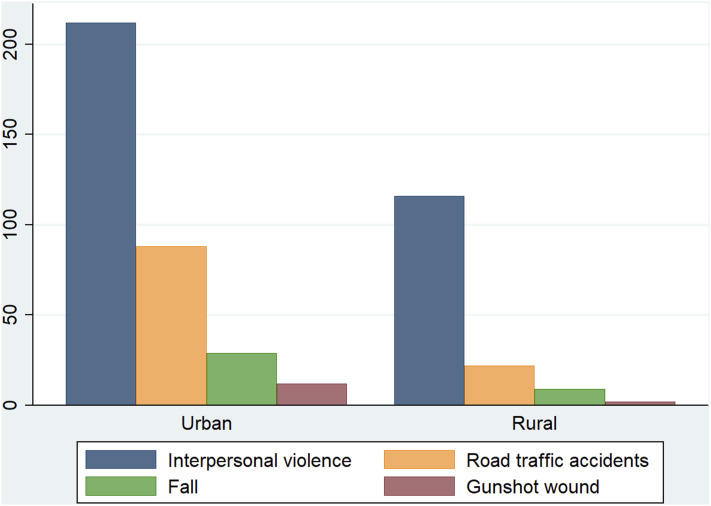

Of the 490 patients, 341 live in urban areas (70%), and 149 live in rural areas; the urban-rural ratio was 2.3 to 1, as seen in Figure 3. In both regions, the trauma mechanism of facial fracture was interpersonal violence (P < .001).

Figure 3.

Frequency of facial fracture patterns by place of residence in 490 midface and mandibular fractures cases.

Facial Bone Fractures and Trauma Mechanism

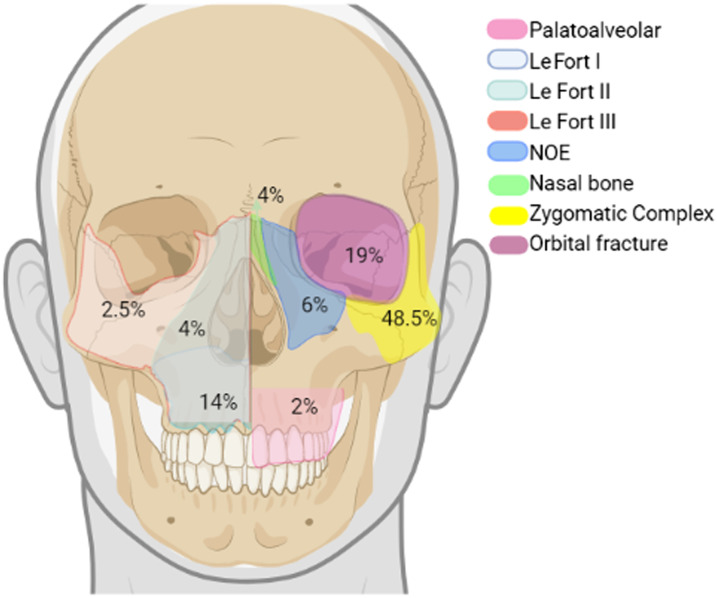

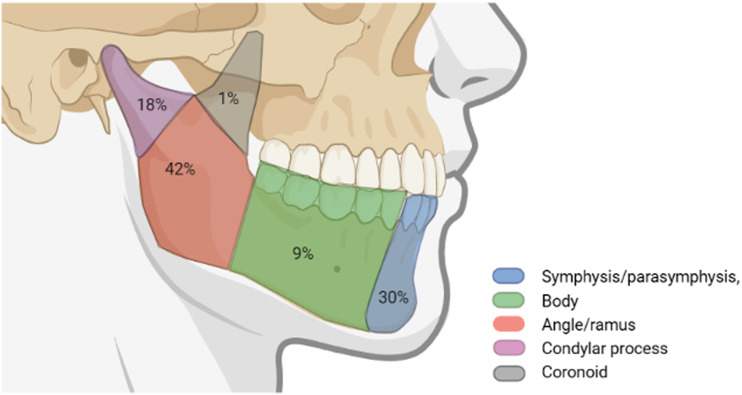

The total fracture sites were 490, amongst which mandibular fractures were the highest (52.2%) (P < .001). The distribution of facial fractures in the midface and mandible as seen in Table 1. The most common facial fracture in the 16–29 group was mandible fracture 52%, and in the 30–49 group, it was midface fracture 42.6%. In 490 patients, 237 midface fractures were subdivided into specific groups, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Midface fracture distribution. Created with BioRender.com.

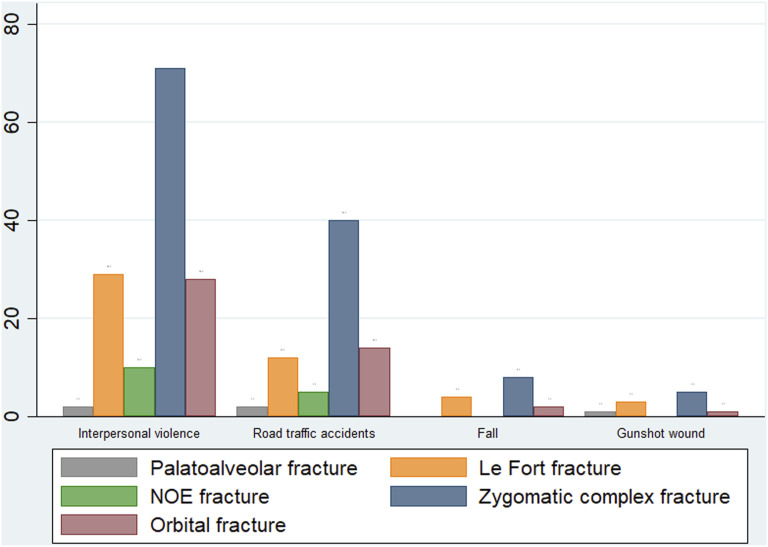

The most frequent diagnosis was a zygomatic complex fracture at 48.5%, followed by an orbital fracture at 19% and Le Fort I at 14%. For all trauma mechanisms, the most frequent fracture was the zygomatic complex fracture, as seen in Figure 5. In the midface fractures, no significant difference in the distribution was found in gender, age groups, place of residence, trauma mechanism, and treatment, as seen in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Association of facial bone fractures and trauma mechanism in midface fracture.

Table 2.

Distribution of midface fractures according to anatomic site.

| Palatoalveolar, % | Le Fort | NOE, % | Nasal, % | Zygomatic Complex, % | Orbital, % | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | |||||||

| Gender | .876 | ||||||||

| Female | 5.7 | 16.8% | 0% | 0% | 5.6 | 0 | 50.0 | 22.2 | |

| Male | 1.8 | 13.7% | 4.6% | 2.7% | 5.2 | 4.6 | 48.4 | 18.3 | |

| Age | .104 | ||||||||

| 16-29 | 2.1 | 13.7% | 4.2% | 3.1% | 3.1 | 8.2 | 45.2 | 20.0 | |

| 30-49 | 3.0 | 11.9% | 4.9% | .9% | 9.9 | 0 | 54.5 | 14.8 | |

| >50 | 0 | 19.5% | 2.4% | 4.9% | 2.4 | 4.9 | 41.5 | 24.4 | |

| Trauma mechanism | .886 | ||||||||

| Interpersonal violence | 1.4 | 13.6% | 4.3% | 3.6% | 6.4 | 4.3 | 47.1 | 19.3 | |

| Road traffic accidents | 2.7 | 11.0% | 4.1% | 1.4% | 6.9 | 2.7 | 52.0 | 19.1 | |

| Fall | 0 | 28.6% | 0% | 0% | 0 | 7.1 | 50.0 | 14.3 | |

| Gunshot wound | 10.0 | 20.0% | 10.0% | 0% | 0 | 10.0 | 40.0 | 10.0 | |

| Place of residence | .105 | ||||||||

| Urban | 1.4 | 14.3% | 4.0% | 2.0% | 4.8 | 6.8 | 45.6 | 21.0 | |

| Rural | 3.3 | 13.3% | 4.4% | 3.3% | 7.9 | 0 | 53.3 | 14.4 | |

| Treatment | .490 | ||||||||

| ORIF | 2.8 | 12.4% | 3.9% | 3.4% | 6.2 | 5.0 | 49.1 | 16.9 | |

| Closed | 0 | 18.3% | 5.0% | 0% | 5.0 | 1.7 | 46.7 | 23.3 | |

ORIF: open reduction and internal fixation.

Fisher’s exact.

*P < .05.

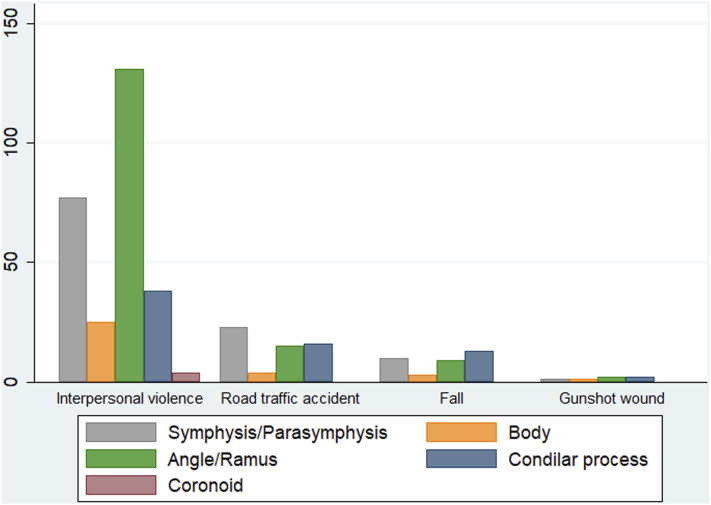

In 490 patients, 253 mandible fractures were subdivided into specific groups, as seen in Figure 6. The most common fracture site in females was the condylar process at 40.6%; in contrast, the most common in males was angle/ramus fracture at 44.4%. The most frequent fracture site in all age groups was angle/ramus fracture. In interpersonal violence, the most common fracture site was angle/ramus fracture at 47.6%; in road traffic accidents, the most common fracture site was symphysis/parasymphysis fracture at 39.7%, and in falls, the most common fracture site was condylar process fracture at 37.1%, as seen in Figure 7. The most associated fracture sites in a triple mandibular fracture were condylar process symphysis/parasymphysis and angle/ramus fractures. The most frequent fracture in both treatments was the angle/ramus fracture, as seen in Table 3. This distribution was statistically significant (P < .001).

Figure 6.

Mandible fracture distribution. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 7.

Association of facial bone fractures and trauma mechanism in mandible fractures.

Table 3.

Distribution of mandible fractures according to anatomic site.

| Symphysis/Parasymphysis, % | Body, % | Angle/Ramus, % | Condylar Process, % | Coronoid, % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .003* a | |||||

| Female | 37.5 | 6.2 | 15.6 | 40.6 | 0 | |

| Male | 28.9 | 9.1 | 44.4 | 16.4 | 1.1 | |

| Age | .005* b | |||||

| 16-29 | 32.2 | 3.5 | 47.7 | 15.6 | 1 | |

| 30-49 | 27.5 | 14.1 | 36.6 | 20.4 | 1.4 | |

| >50 | 24.2 | 18.2 | 30.3 | 27.3 | 0 | |

| Trauma mechanism | .011* a | |||||

| Interpersonal violence | 28 | 9.1 | 47.6 | 13.8 | 1.5 | |

| Road traffic accidents | 39.7 | 6.9 | 25.9 | 27.6 | 0 | |

| Fall | 28.6 | 8.6 | 25.7 | 37.1 | 0 | |

| Gunshot wound | 16.7 | 16.7 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 0 | |

| Place of residence | .003* b | |||||

| Urban | 29.9 | 7.2 | 46.4 | 15.5 | 1 | |

| Rural | 28.9 | 14.5 | 26.5 | 28.9 | 1 | |

| Number of fractures | <.001* a | |||||

| Simple fracture | 25.5 | 9 | 49 | 16.6 | 0 | |

| Double fracture | 35.4 | 7.3 | 42.7 | 12.5 | 2 | |

| Triple-fracture | 16.2 | 16.2 | 10.8 | 56.8 | 0 | |

| Treatment | .588 a | |||||

| ORIF | 30.9 | 8.6 | 40.5 | 18.6 | 0 | |

| Closed | 26 | 9.6 | 46.2 | 18.2 | 1.5 |

ORIF: open reduction and internal fixation.

a Fisher’s exact.

*P < .05.

b Chi2.

Treatment

The procedures considered closed treatment are intermaxillary fixation and closed treatments with reduction, such as the Gillies approach to ZMC. No patient was treated with a soft diet and observation in the study group.

The most frequent treatment of facial fractures was open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) at 73% (n = 358). The treatment of choice in all trauma mechanisms and fracture sites was ORIF in facial fractures. Falls were the most frequent trauma mechanism treated with closed treatment at 37%, followed by interpersonal violence at 29%. Road traffic accidents were the most frequent trauma mechanism treated with ORIF, followed by gunshot wounds (P = .588).

Discussion

This study describes the patterns, trauma mechanism, and treatment of facial fractures in Balbuena General Hospital in Mexico over 3-year. Various studies on the incidence of facial fractures in different countries have been studied. The results of epidemiological studies on the causes and incidence of maxillofacial fractures tend to vary with geographic location, socioeconomic status, culture, religion of the region, and era.3,4,12

Age and Sex Distribution

The predominance of a male was a relatively consistent finding in most studies, including the present.3,4,9,12 Medina-Solis et al reported that facial fractures in Mexico’s Department of Social Security of Campeche had a 12: 1 male to female ratio, and the age group was 20–29 years with 29.96% of all midface fractures. In other Latin American regions, such as Brazil, Leite et al reported that 83.47% were male and 16.53% were female. The age group most affected was the 21–30 years group in males and the 11–20 years group in females. 13 Similarly, in this study, there was a predominance of males to females; the most frequent group was the 16–29 years group.

Facial Bone Fractures and Trauma Mechanism

Previous studies reported that the most fractured sites involved are the mandible, nasal bone, and maxillary zygoma.8,9,12 Similarly, in this study, the most frequent diagnosis was a mandible fracture, and in the midface was a zygomatic complex fracture, followed by internal orbit fracture and nasal fracture. The most associated fracture sites in a mandibular fracture were angle/ramus fractures, symphysis/parasymphysis, and condylar process.

According to various authors,8,9,12-14 traffic accidents were the most frequent cause of fracture, followed by falls and physical aggression. Lee reported that interpersonal violence was the most common trauma mechanism in maxillofacial fractures in New Zealand. 3 This study shows that interpersonal violence was more frequent in males in the 30–49 age group and females in the 16–29 age group, probably due to the geographic location of the Hospital and the increase in interpersonal violence in México. Most patients came from urban areas due to the location of the hospital within the metropolitan area.

Exposed data can be used to improve regional policies regarding interpersonal violence. Policies to enhance intrapersonal violence are based on working with alliances to prevent and respond to violence through evidence-based strategies and techniques. PAHO’s (Pan American Health Organization) priorities regarding this point are aimed at: (1) Raising awareness of the need for action to reduce violence in the Region of the Americas; (2) Identify, synthesize and disseminate evidence on what works to reduce violence; (3) Provide guidance and technical support to countries to develop evidence-based prevention and response capacity; (4) Strengthen partnerships across sectors and stakeholders for violence prevention and response.17 Countries with high levels of violence should implement these key PAHO priorities to reduce intrapersonal violence.

Treatment

Kraft et al. observed changing patterns of facial trauma in treatment and management options for rehabilitation and reconstruction patients suffering from facial trauma. 9 Some authors describe treatment with closed reduction predominantly before twenty century in developing countries. Lee’s study of mandibular fractures in Australia shows that almost half of all patients were treated conservatively. This study found no statistically significant difference between treatment and anatomic site. Probably a large percentage of conservative treatments were due to the displacement of these fractures that did not meet the surgical criteria. Interpersonal violence is considered a low energy trauma; perhaps this produces non-displaced fractures which deserve conservative treatment.

The indications for observation treatment are mainly stable fractures without displacement, minimal displacement of the fracture, and the patient’s general condition that does not allow surgical intervention. The reason is that public hospitals are governed by a system of reference by levels of care. Patients with minimal or no fracture displacement are treated in lower-level hospitals.

The current study has some limitations. First, the patients in this study are from the lower-middle economic class. For this reason, they probably do not have a vehicle, reducing the incidence of fractures due to traffic accidents. Second, this study analyzed the records of patients treated for facial fractures, excluding cervical fractures, skull base, and cranial vault trauma. Lalloo et al 12 described a considerable risk of concomitant intracranial and cervical spine injuries with facial bone trauma. We recommended future research to investigate this possible relationship between facial fractures and cervical injuries. Lastly, reducing interpersonal violence should focus on reducing the availability and excessive consumption of alcohol, promoting gender equality to prevent violence against women, establishing identification, care, and support programs for victims, and increasing control of the police in high-incidence areas.

Conclusion

The analysis provides information that can help to focus preventive measures regarding facial fractures, especially on efforts to reduce interpersonal violence.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: The chief approved this study of the Maxillofacial Surgery service of the Balbuena General Hospital in Mexico City. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study.

ORCID iD

Delgado-Piedra Daniel, DDS, Msc https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6975-5143

References

- 1.Lalloo R, Lucchesi LR, Bisignano C, et al. Epidemiology of facial fractures: incidence, prevalence and years lived with disability estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study. Inj Prev. 2020;26:i27-i35. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allareddy V, Allareddy V, Nalliah RP. Epidemiology of Facial Fracture Injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(10):2613-2618. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee K. Global Trends in Maxillofacial Fractures. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012;5(4):213-222. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1322535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaddipati R, Ramisetti S, Vura N, Reddy KR, Nalamolu B. Analysis of 1, 545 Fractures of Facial Region—A Retrospective Study. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015;8(4):307-314. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1549015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd JP, Bisson JI. Towards integrated health care: A model for assault victims. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(JAN):3-4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadre KS, Halli R, Joshi S, et al. Incidence and Pattern of Cranio-Maxillofacial Injuries : A 22 year Retrospective Analysis of Cases Operated at Major Trauma Hospitals/Centres in Pune. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 2013;12(4):372-378. 10.1007/s12663-012-0446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arif Z, Rajanikanth BR, Prasad K. The Role of Helmet Fastening in Motorcycle Road Traffic Accidents. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2019;12(4):284-290. doi: 10.1055/S-0039-1685458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gassner R, Tuli T, Hächl O, Rudisch A, Ulmer H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9543 cases with 21067 injuries. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2003;31(1):51-61. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(02)00168-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraft A, Abermann E, Stigler R, et al. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: Synopsis of 14, 654 Cases with 35, 129 Injuries in 15 Years. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012;5(1):41-49. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1293520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Audlin J, Tipirneni K, Ryan J. Facial Trauma Patterns Among Young Athletes. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2021;14(3):218-223. doi: 10.1177/1943387520966424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu FC, Halsey JN, Oleck NC, Lee ES, Granick MS. Facial Fractures as a Result of Falls in the Elderly: Concomitant Injuries and Management Strategies. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2019;12(1):45-53. doi: 10.1055/S-0038-1642034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lalloo R, Lucchesi LR, Bisignano C, et al. Epidemiology of facial fractures: Incidence, prevalence and years lived with disability estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study. Inj Prev. 2019;26:i27-i35. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leite A, Campos M, Vasconcelos B. Perfil epidemiológico de pacientes portadores de fraturas faciais. Rev Ciênc Méd, Campinas. 2005;14(4):345-350. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elarabi MS, Bataineh AB. Changing pattern and etiology of maxillofacial fractures during the civil uprising in Western Libya. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23(2):e248-e255. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]