Abstract

Monitoring yellow fever in non-human primates (NHPs) is an early warning system for sylvatic yellow fever outbreaks, aiding in preventing human cases. However, current diagnostic tests for this disease, primarily relying on RT-qPCR, are complex and costly. Therefore, there is a critical need for simpler and more cost-effective methods to detect yellow fever virus (YFV) infection in NHPs, enabling early identification of viral circulation. In this study, an RT-LAMP assay for detecting YFV in NHP samples was developed and validated. Two sets of RT-LAMP primers targeting the YFV NS5 and E genes were designed and tested together with a third primer set to the NS1 locus using NHP tissue samples from Southern Brazil. The results were visualized by colorimetry and compared to the RT-qPCR test. Standardization and validation of the RT-LAMP assay demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity compared to RT-qPCR, with a detection limit of 12 PFU/mL. Additionally, the cross-reactivity test with other flaviviruses confirmed a specificity of 100%. Our newly developed RT-LAMP diagnostic test for YFV in NHP samples will significantly contribute to yellow fever monitoring efforts, providing a simpler and more accessible method for viral early detection. This advancement holds promise for enhancing surveillance and ultimately preventing the spread of yellow fever.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Yellow fever virus, Yellow fever, RT-LAMP

Subject terms: Infectious-disease diagnostics, Molecular biology

Introduction

Yellow fever (YF) is a reemerging zoonotic disease transmitted by mosquitoes that affects both humans and non-human primates (NHP)1,2. The disease is caused by the yellow fever virus (YFV), which belongs to the Flavivirus genus. This genus also includes well-known viruses such as the Dengue virus (DENV) and Zika virus (ZIKV)3. YFV has a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 11,000 nucleotides. This genome encodes a polyprotein with three structural proteins (capsid—C, membrane—M, and envelope—E) and seven non-structural proteins (NS1 to NS5)4,5. YFV has seven known genotypes: five in Africa (West Africa I and II, East Africa, East/Central Africa, and Angola) and two in the Americas (South America I and II), with the South American genotypes originating from the West African ones6. In Brazil, the predominant genotype is South America I, which includes five distinct lineages (1A–1E). Historically, lineages 1A, 1B and 1C were common in South America until the mid-1990s, when they were largely replaced by the current lineages 1D and 1E6,7.

The YF is sustained through two fundamental cycles: urban and sylvatic. In the urban cycle, Aedes aegypti transmits the virus to humans, while in the sylvatic cycle, various mosquito species, particularly those of the genera Haemagogus and Sabethes, play a crucial role in South America’s transmission. The NHP serves as the primary sylvatic host for YFV and acts as a virus-amplifying and highly susceptible host2. In recent years, the re-emergence of YFV has significantly impacted public health in Brazil. Since 2002, YFV has expanded its circulation, spreading from the East towards the South of Brazil. During these outbreaks, thousands of NHP deaths were documented, and over 2100 human cases were reported, with a case fatality rate of approximately 30%8.

The focus of YF surveillance in Brazil is centered on three key areas: monitoring human cases, entomology, and epizootics in NHP9. Epizootic events involving YF are crucial for predicting and identifying human cases of the disease10. Therefore, NHP surveillance aims to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease by investigating suspected epizootics, identifying YFV circulation, and preventing its transmission to humans9. However, YFV detection is hampered because it is conducted in a few national reference laboratories far from the NHP epizootic sites, limiting detailed spatiotemporal tracking of YFV incidence in Brazilian microregions8.

The gold standard for detecting YFV RNA is molecular diagnostics using RT-qPCR11. However, this method is costly, and requires specialized equipment and skilled personnel, making it incompatible with point-of-care (POC) applications12. Consequently, such analyses are usually performed in central reference laboratories, prolonging the diagnostic process11,13. The loop-mediated isothermal amplification technique (RT-LAMP)14 is a valuable, rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective alternative to the gold standard RT-qPCR for monitoring diseases. This nucleic acid amplification method works under isothermal conditions, with results visible to the naked eye15,16. In this study, an RT-LAMP molecular assay for YFV diagnostics in NHP tissues was developed and validated. This diagnostic pipeline aids in early virus detection, especially in areas experiencing outbreaks. It enables decentralized testing, allowing for rapid implementation of preventive measures11.

Materials and methods

Collection of NHP tissue samples

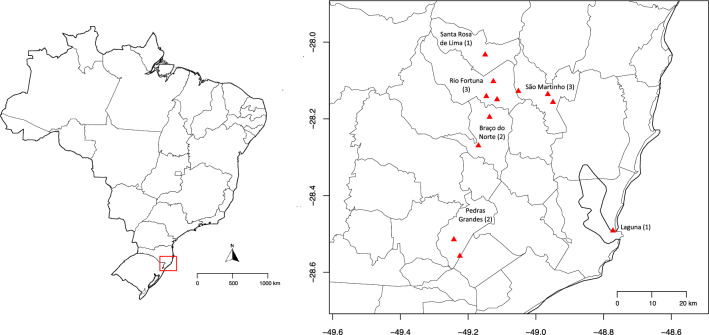

The biological samples analyzed in this study were obtained from NHP epizootics events in municipalities within the Southern region of Santa Catarina State (Southern Brazil). The specimens were collected by the Santa Catarina State Epidemiological Surveillance Service (Fig. 1). The state government collected tissue fragments from NHP carcasses, stored them in cryotubes, froze them, and transported them to the Central Public Health Laboratory (LACEN/SC), and subsequently to the FIOCRUZ reference laboratory (Carlos Chagas Institute, PR—Brazil) for official YFV molecular diagnosis by RT-qPCR technique. Simultaneously, approximately 0.5 cm2 pieces of tissue were collected for this study, preserved in RNAlater stabilization solution (Invitrogen—Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and stored at − 20 °C until the moment of viral RNA extraction. A total of 12 NHP epizootics, sampled between March 2021 and February 2022, were processed and analyzed. In each collection, tissues from five types were obtained: spleen, heart, liver, lung, and kidney, resulting in a total of 60 tissues analyzed. Epidemiological data for each NHP sample are detailed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Collection sites for non-human primate (NHP) tissues in municipalities from the Southern region of Santa Catarina State, Brazil. The left side features a map of Brazil, while the right side provides a magnified view of the red box from the Brazil map, indicating the specific sample collection sites (red triangles). The x and y axes on the right map represent longitude and latitude, respectively. The number of collections from each municipality is shown in parentheses. The maps were generated using the sf, maps, and mapdata packages17–20 from R Software, version 4.3.121.

Table 1.

Epidemiological data summary for non-human primate (NHP) samples.

| Municipality | Sample identification | Collection date | SINAN number | Host | Sample type | RT-qPCR Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rio Fortuna | 1 | 03/03/2021 | 4563807 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 2 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 3 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 4 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 5 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Santa Rosa de Lima | 6 | 05/03/2021 | 1414470 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 7 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 8 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 9 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 10 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Braço do Norte | 11 | 06/03/2021 | 5069209 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 12 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 13 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 14 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 15 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Rio Fortuna | 16 | 08/03/2021 | 4563814 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 17 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 18 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 19 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 20 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| São Martinho | 21 | 13/03/2021 | 4606986 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 22 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 23 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 24 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 25 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Rio Fortuna | 26 | 16/03/2021 | 4563818 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 27 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 28 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 29 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 30 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| São Martinho | 31 | 17/03/2021 | 4606990 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 32 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 33 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 34 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 35 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| São Martinho | 36 | 06/04/2021 | 5175026 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 37 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 38 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 39 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 40 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Pedras Grandes | 41 | 23/11/2021 | 3229070 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 42 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 43 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 44 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 45 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Pedras Grandes | 46 | 24/11/2021 | 3229071 | Allouatta genus | Spleen | Detectable |

| 47 | Heart | Detectable | ||||

| 48 | Liver | Detectable | ||||

| 49 | Lung | Detectable | ||||

| 50 | Kidney | Detectable | ||||

| Braço do Norte | 51 | 31/03/2021 | 5069214 | Callithrix genus | Spleen | Not detectable |

| 52 | Heart | Not detectable | ||||

| 53 | Liver | Not detectable | ||||

| 54 | Lung | Not detectable | ||||

| 55 | Kidney | Not detectable | ||||

| Laguna | 56 | 19/02/2022 | 8285928 | Cepajus genus | Spleen | Not detectable |

| 57 | Heart | Not detectable | ||||

| 58 | Liver | Not detectable | ||||

| 59 | Lung | Not detectable | ||||

| 60 | Kidney | Not detectable |

Municipality: location where the sample was collected. Sample identification: a unique code (1–60) was assigned to each tissue sample obtained from 12 NHP collections, with a total of 60 tissues analyzed. Collection date: date of sample collection. SINAN number: identification number in the National Notifiable Diseases Information System. Host: species of the host. Sample type: tissues from five types (spleen, heart, liver, lung, and kidney) obtained in each of the 12 collections. RT-qPCR: results of the RT-qPCR test from the FIOCRUZ reference laboratory (Carlos Chagas Institute, PR-Brazil).

Primer design for YFV

Around 50 complete YFV genomes from GenBank were analyzed to identify conserved genomic regions for primer design. These genomes, obtained from Brazilian isolates (Table S1), identified from 2000 to 2021, were realigned using the Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment tool (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/tools/msa/clustalo). Following the identification of regions with the highest homology among all strains, based on the NS5 and E gene sequences, a single consensus sequence was generated to design degenerated primers for these genes using the NEB LAMP Primer Design Tool v1.4.1 (available at https://lamp.neb.com).

The designed primer sets contained: forward primer (F3), backward primer (B3), forward inner primer (FIP), and backward inner primer (BIP) (Fig. S1). A TTTT linker sequence was included between the two components of FIP (F1c/F2) and BIP (B1c/B2), as this has been reported to improve the reaction by increasing hybridization sensitivity22. The YFV designed primers were compared with the available NS5 and E genes Flavivirus sequences (from DENV and ZIKV) to avoid cross-reaction.

Viral RNA extraction

Viral RNA was extracted from NHP tissue fragments weighing between 10 and 30 mg each. The samples were placed in Eppendorf tubes with 600 µL of lysis solution—Monarch Total RNA MiniPrep kit (New England BioLabs). After maceration for homogeneity, RNA extraction was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was eluted in 50 µL of nuclease-free water and stored at − 80 °C. RNA quantification was performed using the Qubit RNA BR Assay Kit (Q10210) and Qubit 4 fluorometer Invitrogen (Thermo Fischer Scientific).

RT-LAMP reaction

The RT-LAMP assay used three primer sets targeting NS1 (described by Nunes et al.13), NS5, and E genes specifically designed in this study (Table 2). All primers were resuspended in nuclease-free water and combined to make a 10 × primer mix as follows for each set: FIP and BIP (16 μM each), F3 and B3 (2 μM each), LF and LB (4 μM each). The RT-LAMP reaction contained 12.5 of 2X WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP Master Mix (New England BioLabs, Protocol M1800), 2.5 μL from each of the 10 × primer mixes, 4 μL of target RNA, and RNase-free water totaling 25 μL. The reactions were carried out in 0.2 mL microtubes and incubated in a dry bath (Kasvi) at 65 °C for 40 min. Results were visually interpreted, with pink indicating negative and yellow indicating positive results, and recorded using a smartphone camera.

Table 2.

Sequences of primers used in RT-LAMP assays.

| Target | Primers Sequence (5′ → 3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| NS1* | F3 | TCCACACCYTGGAGRCAYTR |

| B3 | GYCCATCACAGYYGCCRTCA | |

| FIP | GRCCTCCGATTGAYCTCGGCTTTARTGTGARTGGCCRCTGAC | |

| BIP | GGTYCAGACRAACGGACCTTGGTTTYCCTGGGCAAGCTTCTCT | |

| LF | CTTCAACTGATGTTCCAATCGTATG | |

| LB | ATGCAGGTRCCACTAGAAGTGA | |

| NS5 | F3 | GAACAGTGGAAGACTGCCAA |

| B3 | CAGCCACATGTACCAGATGG | |

| FIP | GCTGATGCARCCGTCGTTCYTCTTTTTGAAGCTGTCCAAGATCCGA | |

| BIP | GGCAGGTGCCGRACTTGTGTTTTTCGCCTTTCCAAACTCTGACA | |

| E | F3 | TTYATTGAGGGGGTGCATGG |

| B3 | CAAGTGGGCTTCACCAGTG | |

| FIP | GTCYAGTGAAGGCTTGTCRGGGTTTTTGGGTTTCAGCCACYTTG | |

| BIP | TGCCATTGATGGACCYGCTGARTTTTGGGGCACTTGTCATTGATCT | |

| ACTB* | F3 | AGTACCCCATCGAGCACG |

| B3 | AGCCTGGATAGCAACGTACA | |

| FIP | GAGCCACACGCAGCTCATTGTATCACCAACTGGGACGACA | |

| BIP | CTGAACCCCAAGGCCAACCGGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGGTC | |

| LF | TGTGGTGCCAGATTTTCTCCA | |

| LB | CGAGAAGATGACCCAGATCATGT |

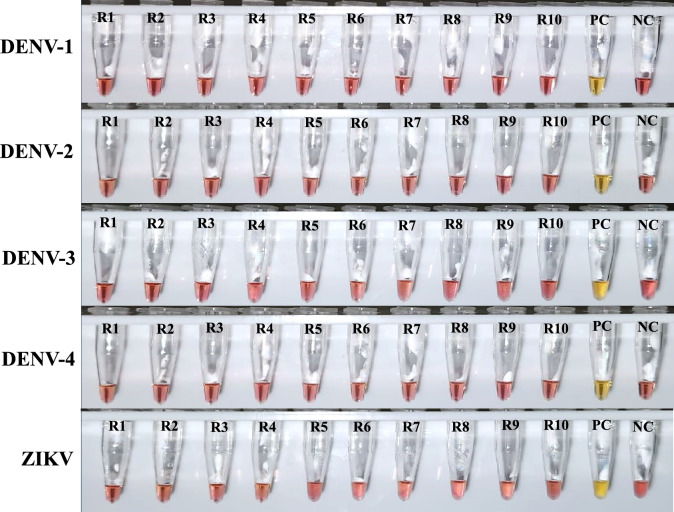

Analytical specificity of RT-LAMP assays

To evaluate the specificity of the RT-LAMP assay for YFV detection, different flaviviruses RNA were tested, including Dengue (DENV-1: DV1 BR90; DENV-2: ICC 265; DENV-3: DV3 BR98; DENV-4: TVT 360) and Zika viruses (ZIKV: BR 2015/15261). Tests were performed in ten independent replicates per protocol, in addition to positive control containing YFV RNA (vaccine strain 17D), and negative controls using nuclease-free water instead of RNA.

Furthermore, RT-LAMP assays were conducted to detect YFV in samples containing other flaviviruses. Different pools of RNA were tested, one set containing RNA from DENV1-4, ZIKV, and YFV, and another set containing RNA from DENV1-4 and ZIKV, but excluding YFV. These RT-LAMP assays were performed in independent triplicates.

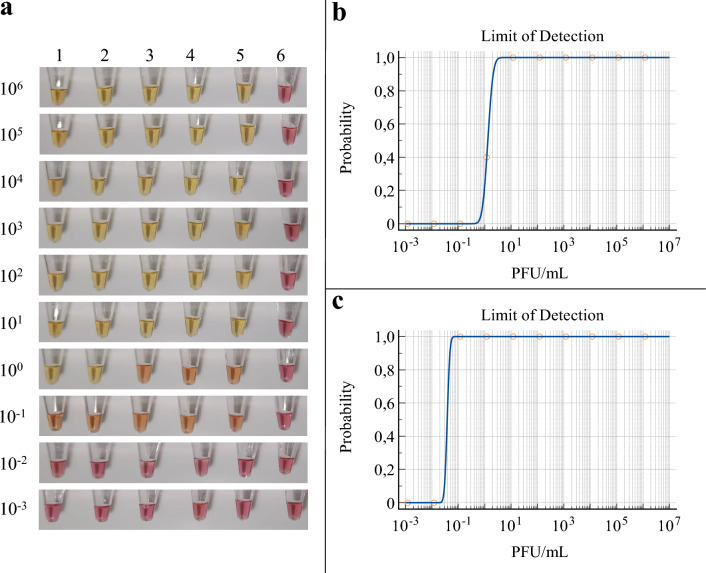

Analytical sensitivity of RT-LAMP assays

To evaluate the sensitivity (detection limit) of the RT-LAMP assay for YFV, a ten-fold dilution series of RNA extracted from the supernatant of YFV-infected Vero cells (strain ES-504) was used, with titers ranging from 1.2 × 106 to 1.2 × 10−3 PFU/mL. After dilution, the samples were tested directly in RT-LAMP, with a negative control included. The assays were conducted in five separate runs and analyzed using probit regression with MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium; www.medcalc.org; 2020).

Evaluation and validation of RT-LAMP assays with NHP tissue samples

To validate RT-LAMP for diagnosing YFV in NHP tissues, 60 viscera samples were tested (Table 1). All RT-LAMP assays with NHP tissue samples were performed in triplicates. The same assays were also repeated using the endogenous control β-actin from vertebrates as described by Zhang et al.23, with some modifications. Each RT-LAMP assay included a negative control (using nuclease-free water instead of RNA) and a positive control containing YFV RNA (vaccine strain 17D). We compared our RT-LAMP results with RT-qPCR assays official results from the national health authority performed at ICC/FIOCRUZ reference laboratory (Carlos Chagas Institute, PR-Brazil) to assess accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity (unpublished data).

Results

Assessment of RT-LAMP primer for YFV with NHP tissues

Each primer set (Table 2) was individually tested with NHP tissue samples. The NS5 and E primers, specifically designed for YFV detection in Brazil, effectively identified the virus in the samples. Despite Nunes et al.13 primer targeting the NS1 gene failing to amplify the recent Southern Brazilian circulating YFV strains, it successfully amplified the YFV vaccine strain 17D used as a positive control. Thus, we chose to keep this primer in the protocol due to its ability to amplify strains from other regions of the world. Next, the combination of all three sets of primers (NS5, E, and NS1) was tested in a single RT-LAMP reaction. The assay time was optimized to 40 min, compared to the 50 min required when each set of primers was evaluated individually. The RT-LAMP results matched the RT-qPCR assays conducted by the national health authorities at FIOCRUZ in the analysis of 60 different tissues from 12 NHP epizootics events. Out of the 60 NHP samples tested with RT-qPCR, 10 were negative, and the remaining 50 were positive (Table 1), consistent with the RT-LAMP assay results conducted with three replicates of each tissue sample (Fig. 2), showing 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Each code in Table 1 (Sample identification 1–60) corresponds to the tests presented in Fig. 2. All 60 samples tested positive with the RT-LAMP assay targeting the vertebrate endogenous control β-actin (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

YFV detection in NHP tissue samples using RT-LAMP with three primers set (NS5, E, and NS1). Amplification products were visually inspected, with pink indicating negative and yellow indicating positive results. 1–50: positive results, 51–60: negative results, NC: negative control using nuclease-free water instead of RNA, PC: positive control with YFV RNA (vaccine strain 17D). Each code in Table 1 (sample identification 1–60) corresponds to the tests presented in this figure.

Analytical specificity and sensitivity assessment of RT-LAMP assays

The RT-LAMP assay for YFV detection showed no cross-reaction with other viruses from the Flavivirus genus (DENV1-4 and ZIKV). The results were negative across all ten replicates of the analyzed viruses (Fig. 3). Additionally, an RT-LAMP assay was conducted to detect YFV in samples containing other flaviviruses, testing pools including RNA from DENV1-4, ZIKV, and YFV, and pools with the same set of viruses, but excluding YFV. Positive results were only observed in experiments involving pools containing YFV. Conversely, samples from pools without YFV yielded negative results across all three replicates (Fig. S3). Notably, no amplification was detected in negative controls containing water, whereas positive controls containing YFV RNA consistently exhibited amplification.

Fig. 3.

RT-LAMP specificity test assay for YFV detection. The RNA of other flaviviruses circulating in Brazil were tested, including Dengue (DENV-1: DV1 BR90; DENV-2: ICC 265; DENV-3: DV3 BR98; DENV-4: DVT 360) and Zika viruses (ZIKV: BR 2015/15,261). R1–R10: ten independent replicates containing Flavivirus RNA, PC: positive control containing YFV RNA (vaccine strain 17D), NC: negative control using nuclease-free water instead of RNA. Amplification products were visually inspected, with pink indicating negative and yellow indicating positive results.

Serial dilutions of YFV (strain ES-504) were used to test the sensitivity (limit of detection) of the RT-LAMP assay for diagnosing YFV. A concentration of 1.2 × 101 PFU/mL demonstrated 100% positive performance (Fig. 4a), while the probit regression analysis resulted in a limit of detection (within 95% reliability) of 2,4 PFU/mL (p < 0,0001) (Fig. 4b). When considering the orange results as positive (Fig. 4a), the limit of detection of the assay was 1, 2 × 10−1 PFU/mL, and the probit regression analysis resulted in a limit of detection (within 95% reliability) of 5 × 10−1 (p < 0,0001) (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity of YFV RT-LAMP assay. (a) Assay colorimetric results of five replicates (1–5) and a negative control with water (6) tested with a serial dilution of YFV RNA (106–10−3 PFU/mL). (b) Limit of detection of 101 PFU/mL established through the probit regression analysis and considering only yellow results as positive. (c) Limit of detection of 10−1 PFU/mL established through the probit regression analysis and considering yellow and orange results as positive.

Discussion

Labor-intensive techniques (e.g.: RT-qPCR) impede early detection of YFV in NHP, humans, and mosquitoes, delaying the implementation of YF surveillance programs due to the need for specialized equipment and skilled technicians24. In this study, RT-LAMP assays using three primers targeting different molecular regions (NS1, NS5, and E) streamline YFV detection, reducing processing time compared to RT-qPCR, and overcoming limitations in early YFV detection through both molecular and serological methods25,26.

Initial experiments revealed that the NS1 primer for YFV13 failed to amplify South American strains (Accession numbers: OP508651.1, OP508679.1, OP508678.1, OP508680.1, OP508683.1, OP508684.1, OP508652.1) from a recent outbreak in Southern Brazil (2019–2021). This failure was due to genetic polymorphisms at the primer binding site, as it was originally designed based on older strains from Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Panama, Peru, Trinidad, Venezuela, the vaccine strain, and Brazil that circulated between 1980 and 200213. Indeed, Meagher et al.27 noted that the NS1 region is not completely conserved in all YFV lineages. To tackle this, in this study new degenerate primers targeting conserved NS5 and E regions of the YFV genome were designed to broaden coverage across multiple virus strains, enhancing test robustness and sensitivity27. These, alongside the NS1 primer13, were employed in RT-LAMP reactions for specific YFV RNA detection. Therefore, it is recommended to periodically review the YFV diagnostic primers used in both RT-qPCR or RT-LAMP assays to identify mutations and reduce the risk of false negatives. In addition to accounting for polymorphisms at the primer binding site, it is essential to thoroughly assess the risk of primer dimerization during the primer design process28, as this can lead to nonspecific amplification and result in false positives29. To mitigate this, primers were designed to avoid complementarity, using the NEB LAMP Primer Design Tool v1.4.1. Primers with the lowest probability of dimerization were selected, and the reaction conditions—including temperature, time, and reagent concentrations—were optimized. Control samples were also used to ensure the accuracy of the tests. Even with these control measures in place, LAMP remains highly effective for diagnostics. It can detect pathogens at very low concentrations, which is essential for managing and controlling rapidly spreading infections30.

Several molecular diagnostic protocols for YFV have been proposed13,24–26,31, yet none have been evaluated using field-collected samples from NHP tissues. Despite Nunes et al.26 findings, which demonstrated higher sensitivity in detecting YFV in experimentally infected hamster liver samples (by PCR and RT-qPCR techniques), the RT-LAMP assay showed potential in detecting YFV across all NHP samples, even in tissues such as lung, heart, and kidney, which are commonly known to have low YFV viral loads2.

The limit of detection identified in this study is found to be equivalent to 12 PFU/mL (Fig. 4a–b), a result like that demonstrated by Nunes et al.13 of 19 PFU/mL using RT-LAMP, and equivalent to those observed using RT-qPCR (9 PFU/mL)26. Following Astari et al.32 findings, which interpret orange results as indicative of amplification, the assay’s detection limit might be even lower than 12 PFU/mL (Fig. 4c). Also, our study found no cross-reaction with other arboviruses, including DENV1-4 and ZIKV, indicating the specificity of the RT-LAMP assay for YFV detection, mitigating a common potential limitation of Flavivirus diagnostic33. Even when other flaviviruses were present in a pooled experiment (DENV1-4 + ZIKV + YFV), the RT-LAMP assay showed high sensitivity, with no interference in YFV detection. Additionally, in the absence of YFV in a flavivirus pool, no amplification occurred, confirming the specificity of the primers designed for YFV detection.

The LAMP technique shows great potential for diagnosing pathogens in remote areas because it is easy to use. Several studies have already standardized LAMP assays for direct analysis without the need for DNA/RNA extraction33–35. Additionally, the lyophilization of LAMP reagents has been validated, allowing them to be stored at room temperature for extended periods34,36, which makes the method suitable for use in areas without refrigeration34,37. Although our study did not investigate RNA extraction alternatives due to the rarity of the NHP samples, or used lyophilized reagents, its aim was to validate a technique that can be used outside of reference laboratories. This approach could accelerate YFV diagnostics and potentially reduce the risk of disease spread to humans. Given the presence of many other arboviruses in resource-limited settings, this technique is crucial for effective monitoring in remote areas. RT-LAMP reactions are already standardized for detecting several arboviruses, including Zika and Dengue38,39. Although standardizing a multiplex LAMP reaction can be challenging due to potential issues such as primer dimerization, some studies have successfully demonstrated the feasibility of using multiplex LAMP assays to identify multiple pathogens in a single test28,40.

The RT-LAMP assay developed for NHPs is expected to detect YFV in humans and mosquitoes, as the primers were designed based on prevalent strains in these groups. It exhibits 100% specificity and sensitivity (Fig. 2, Table 1), comparable to the RT-qPCR technique26, making it a reliable, cost-effective, and user-friendly alternative for YFV molecular diagnosis. It addresses critical gaps present in other protocols25,26, offering easily interpretable results without sophisticated equipment. Our goal is to improve surveillance of NHP epizootics, humans, and mosquitoes, to enable a prompt response to prevent human YFV outbreaks.

Conclusion

Early detection of Yellow Fever in the NHP can assist in the prevention of human epidemics. However, the current diagnostic method (RT-qPCR) is costly, time-consuming, and requires trained personnel, making it impractical for monitoring. New diagnostic technologies should be fast, cheap, sensitive, and usable in decentralized settings. In this study, an RT-LAMP assay for YFV diagnosis was developed with a 40-min incubation time, requiring no trained technicians or expensive equipment. The results are visible to the naked eye, reducing process time. The assay showed 100% specificity and sensitivity, proving robust and reliable for YF diagnosis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Directorate of Epidemiological Surveillance of the State of Santa Catarina (DIVE/SC), Brazil, for collecting the NHP tissue samples, and LACEN/SC for sharing the RT-qPCR official results. This paper is part of the Ph.D. thesis of Sabrina Fernandes Cardoso from the Graduation Program of Cell and Developmental Biology (PPGBCD) at the Biological Sciences Center (CCB) at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC).

Author contributions

S.F.C. drafted the manuscript and collected the NHP tissue samples; S.F.C., A.N.P., A.A.G.Y., I.C.P., and L.D.R.P. participated in data generation and analysis; A.A.G.Y. helped with primer design, experimental design, and molecular analysis; L.W.G., D.C.L., M.S.A.S.N., and D.S.M. helped with all project logistics and molecular analyzes; A.N.P. and L.D.P.R. helped in the paper drafting by critically reading the original manuscript; A.N.P. and L.D.P.R. were the principal investigators, participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by IOC—FIOCRUZ, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development MCTI/CNPq/CAPES/FAPs no 16/2014, Wellcome Trust, 207486/Z/17/Z.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: André N. Pitaluga and Luísa D. P. Rona.

Contributor Information

André N. Pitaluga, Email: pitaluga@ioc.fiocruz.br

Luísa D. P. Rona, Email: luisa.rona@ufsc.br

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74020-4.

References

- 1.McArthur, D. B. Emerging infectious diseases. Nurs. Clin. North. Am.54, 297–311 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasconcelos, P. F. C. Febre amarela [yellow fever]. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop.36, 275–293 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukhopadhyay, S., Kuhn, R. J. & Rossmann, M. G. A. Structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.3, 13–22 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domingo, C., Patel, P., Linke, S., Achazi, K. & Niedrig, M. Molecular diagnosis of flaviviruses. Future Virol.6, 1059–1074 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers, T. J., Hahn, C. S., Galler, R. & Rice, C. M. Flavivirus genome organization, expression and replication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.44, 649–688 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva, N. I. O. et al. Recent sylvatic yellow fever virus transmission in Brazil: the news from an old disease. Virol. J.17, 9–20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mir, D. et al. Phylodynamics of yellow fever virus in the Americas: new insights into the origin of the 2017 Brazilian outbreak. Sci. Rep.7, 7385 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giovanetti, M. et al. Genomic epidemiology unveils the dynamics and spatial corridor behind the yellow fever virus outbreak in Southern Brazil. Sci. Adv.9, eadg9204 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Guia de Vigilância de Epizootias em Primatas não Humanos e Entomologia Aplicada à Vigilância da Febre Amarela. Brasília, v2, (2014).

- 10.Moreno, E. S. et al. Yellow fever epizootics in non-human primates, São Paulo state, Brazil, 2008–2009. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo.55, 45–50 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Febre amarela: guia para profissionais de saúde. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, 1. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 67 (2017).

- 12.Diego, J. G. B. et al. A simple, affordable, rapid, stabilized, colorimetric, versatile RT-LAMP assay to detect SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics (Basel)11, 438 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunes, M. R. T. et al. Analysis of a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) for yellow fever diagnostic. J. Virol. Methods226, 40–51 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notomi, T. et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res.28, E63 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori, Y. & Notomi, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective diagnostic method for infectious diseases. J. Infect. Chemother.15, 62–69 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagamine, K., Hase, T. & Notomi, T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol Cell Probes.16, 223–229 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pebesma, E. & Bivand, R. Spatial data science: With applications 1st edn. (R. Chapman and Hall, Boca Raton, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pebesma, E. Simple features for R: Standardized support for spatial vector data. R J.10, 439–446 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker, R.A., Wilks, A. R., Minka, T.P., Deckmyn, A. maps: Draw Geographical Maps. R package version 3.4.2. (2023).

- 20.Becker, R.A., Wilks, A. R., Brownrigg, R. mapdata: Extra Map Databases. R package version 2.3.1. (2022).

- 21.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foudation for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foudation for Statistical Computing (2014).

- 22.Torres, C. et al. LAVA: An open-source approach to designing LAMP (loop-mediated isothermal amplification) DNA signatures. BMC Bioinform.12, 240 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang, Y. et al. Enhancing colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification speed and sensitivity with guanidine chloride. Biotechniques.69, 178–185 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domingo, C. et al. Advanced yellow fever virus genome detection in point-of-care facilities and reference laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol.50, 4054–4060 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domingo, C. et al. First international external quality assessment study on molecular and serological methods for yellow fever diagnosis. PLoS One.7, e36291 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nunes, M. R. et al. Evaluation of two molecular methods for the detection of yellow fever virus genome. J. Virol. Methods.174, 29–34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meagher, R. J., Priye, A., Light, Y. K., Huang, C. & Wang, E. Impact of primer dimers and self-amplifying hairpins on reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification detection of viral RNA. Analyst16(143), 1924–1933 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das, D., Lin, C. W. & Chuang, H.-S. LAMP-based point-of-care biosensors for rapid pathogen detection. Biosensors12, 1068 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, S. H., Lee, S. Y., Kim, U. & Oh, S. W. Diverse methods of reducing and confirming false-positive results of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta.1280, 341693 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang, S. & Rothman, R. E. PCR-based diagnostics for infectious diseases: Uses, limitations, and future applications in acute-care settings. Lancet Infect. Dis.6, 337–348 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwallah, A. O. et al. A real-time reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the rapid detection of yellow fever virus. J. Virol. Methods193, 23–27 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astari, D. E. et al. Development of a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay with novel quantitative pH biosensor readout method for SARS-CoV-2 detection. APMIS132, 499–506 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva, S. et al. Development and validation of reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) for rapid detection of ZIKV in mosquito samples from Brazil. Sci. Rep.9, 4494 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayashida, K. et al. (2019) Field diagnosis and genotyping of chikungunya virus using a dried reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay and MinION sequencing. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.13, e0007480 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivas-Macho, A., Sorarrain, A., Marimón, J. M., Goñi-de-Cerio, F. & Olabarria, G. Extraction-free colorimetric RT-LAMP detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva. Diagnostics (Basel)13, 2344 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prado, N. O. et al. Development and evaluation of a lyophilization protocol for colorimetric RT-LAMP diagnostic assay for COVID-19. Sci. Rep.14, 10612 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong, Y. P., Othman, S., Lau, Y. L., Radu, S. & Chee, H. Y. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a versatile technique for detection of micro-organisms. J. Appl. Microbiol.3, 626–643 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Jimena, B. et al. Desenvolvimento e validação de ensaios RT-LAMP em tempo real para a detecção específica do vírus Zika. Métodos Mol. Biol.2142, 147–164 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez-Jimena, B. et al. Development and validation of four one-step real-time RT-LAMP assays for specific detection of each dengue virus serotype. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.12, e0006381 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang, Y. et al. Multiplex loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based lateral flow dipstick for simultaneous detection of 3 food-borne pathogens in powdered infant formula. J. Dairy Sci.103, 4002–4012 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.