Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to explore the influence of ward noise management on the mental health and hip joint function of elderly patients post-total hip arthroplasty.

Methods:

The retrospective analysis involved the medical records of 160 elderly patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty at Nanchang First Hospital from March 2021 to January 2023. The observation group received ward noise management (n = 75) and the control group received perioperative routine management (n = 85). The noise level, Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), the Generic Quality of Life Inventory-74 (GQOLI-74), Harris Hip Score (HHS) system, and satisfaction scale were used to evaluate patients. T test and chi-square tests were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

The observation group exhibited a significantly lower noise level compared to the control group (P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in the general information and preoperative SDS, SAS, HHS, and GQOLI-74 scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). No significant differences were observed in the SDS and HHS between the two groups 7 days after the operation (P > 0.05). The observation group presented a significantly lower SAS score than the control group 7 days after the operation (P < 0.05). The score of the observation group 7 days after the operation was lower than that before the operation (P < 0.05). At 7 days after the operation, the observation group showed a higher score in the “social function” dimension of GQOLI-74 compared to the control group (P < 0.05), and the satisfaction of the observation group was significantly higher than that of the control group (94.67 vs. 77.65%, P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Ward noise management can help reduce anxiety among elderly patients after total hip arthroplasty, improve their quality of life and social function, and obtain higher satisfaction.

Keywords: Hip arthroplasty, Noise, Mental health, Anxiety

KEY MESSAGES:

-

(1)

Implementing ward noise management in elderly patients after total hip arthroplasty significantly reduced anxiety levels, fostering a more positive recovery experience.

-

(2)

While noise management didn’t notably affect hip function recovery, patients reported higher satisfaction.

-

(3)

Integrating noise reduction strategies into post-surgical care protocols could enhance patient quality of life following total hip arthroplasty, warranting further investigation and implementation.

Introduction

Hip arthroplasty, as a common clinical treatment for hip diseases, mainly helps in the reconstruction of the joint and repair dysfunction among patients and can considerably reduce the degree of joint pain and prevent deformity.[1] As a result of the increasing aging of the world’s population and the physiological bone degradation in the elderly population, which easily causes osteoporosis, the number of patients undergoing joint replacement surgery worldwide has increased considerably.[2] Most patients experienced anxiety and depression following hip arthroplasty.[3] Anxiety and depression serve as major risk factors for in-hospital complications in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty and are substantially associated with the economic and outcome-related aspects after surgery.[4] The relative proportion of patients undergoing these surgeries with anxiety and depression is rapidly increasing. Pan et al.[5] reported anxiety and depression as risk factors for postoperative pain and complications in patients undertaking joint replacement. In addition, Hawi et al.[6] suggested the possible extreme harm brought about by noise during hip arthroplasty surgery to patient health. Other studies reported that noise can cause headache, fatigue, inattention, restlessness, and other conditions,[7] which may directly affect the rehabilitation process of patients. In addition, noise correlates with the pain intensity of patients,[8,9] which can affect their mood.

Despite the established links between noise and adverse health outcomes, few studies have specifically examined the effects of ward noise management on elderly patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. This study aimed to fill this gap through a retrospective analysis to evaluate the effect of ward noise management on the mental health, quality of life, and hip function of this patient population. In this manner, we can provide new insights into environmental management strategies for the improvement of postoperative patient care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Information

This retrospective research study was approved by the ethics committee of Nanchang First Hospital (approval No. 2024[005]), and all participants gave informed consent. Given that Nanchang First Hospital implemented perioperative routine management for such patients from March 2021 to January 2022, a total of 90 patients admitted during this period were included in the study, and 5 patients who failed to meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The control group included a final number of 85 patients. Ward noise management was implemented in Nanchang First Hospital from February 2022 to January 2023. The study included 81 patients admitted during this period and excluded 6 patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 75 patients were classified as the observation group (perioperative routine management + ward noise management). Finally, the medical records of 160 elderly patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty were collected. General information of patients, including age, sex, body mass index, educational level, average monthly household income, types of disease, type of prosthesis, and noise level, were collected.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unilateral total hip arthroplasty, (2) complete medical records, (3) clear consciousness and normal understanding ability, (4) age ≥≥60 years old, and (5) visual analog scale scores ≤3 at 12, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively.

The exclusion criteria comprised the following: (1) abnormal hearing function, (2) combination with abnormal immune or coagulation function, (3) pathological hip fracture, (4) cognitive dysfunction, (5) malignant tumors, (6) history of ipsilateral hip revision; and (7) severe cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.

METHODS

The control group received perioperative routine management after admission, including routine functional position management, assisting patients to turn over, close monitoring of patients vital signs, implementation of negative-pressure drainage tube nursing, administration of routine pain care, health education, and functional rehabilitation guidance to patients.

The observation group implemented ward noise management based on perioperative routine management, and the steps were as follows. (1) Sound insulation materials were selected for ceilings, walls, doors, and windows and rubber materials for the floor. (2) The training of medical staff and cleaners was strengthened, focusing on the harm brought about by noise to the human body and that the work be four light (namely: softly closing the door, softly speaking, softly operating, and softly walking). In addition, the working hours of medical staff and cleaners were uniformly arranged, with the medical staff being able to concentrate on their operation as much as possible, and the cleaning staff can avoid rest time to minimize the impact on patients. (3) The equipment and instruments in the ward and nurse station were regularly checked, the equipment or items with noise were modified, and special personnel were observed regularly repairing the treatment vehicle to reduce noise. In addition, for the electric monitor in the ward, the appropriate alarm line can be adjusted based on the patient’s condition to reduce the invalid alarm sound. (4) Regular meetings and discussions enabled the department to search for problems and solutions in nursing, with continuous improvement of the nursing process, the establishment of a group responsibility system, implementation of measures for nursing staff to fix beds and bedside workstations, and exertion of their best to care for patients. The nursing staff carefully provided health guidance and nursing services, which allowed them to master the specific conditions of patients in real-time, reducing the number of red light calls and keeping the wards and corridors quiet. (5) The propaganda and education of patients and their families were strengthened, the effect of noise on the disease was discussed, patients and their families were asked not to speak loudly, the visiting time and the number of visitors were clarified, the turnover of personnel in the ward was reduced, and attention was given to the volume of conversation, reminders, and reduced volume of speaking.

Observation Indicators

-

(1)

The scores of each group on Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS)[10] and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)[11] were compared before and after the operation. The two scores were in the range of 20 to 80 points. Mild, moderate, and severe depression had scores between 53 and 62, between 63 and 72, and above 72, respectively. Mild anxiety has a score between 50 and 60, moderate anxiety had a score between 61 and 70, and severe anxiety had a score above 70. Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.896 and 0.902.

-

(2)

The scores on Generic Quality of Life Inventory-74 (GQOLI-74),[12] which involved the dimensions of material life, psychological function, social function, and physical function, were compared between the two groups before and after the operation. Each dimension was scored out of 100, with an elevated score corresponding to an improved quality of life, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.912. Only two dimensions of the scale, namely, material life and social functioning, were used in this study.

-

(3)

After nursing, the satisfaction of each group was evaluated, and the self-made satisfaction scale was used to assess the service attitude and skills of the nursing staff. The full score was 100 points, very satisfied: 80 to 100 points, satisfied: 60 to 79 points, unsatisfied: 0 to 59 points, satisfaction = [(very satisfied) + (satisfied)]/total number of cases × 100%.

-

(4)

Harris Hip Score (HHS) system[13]: The preoperative and postoperative HHSs of each group, including joint mobility, pain, joint deformity, and function, were compared. The full score was 100 points; the higher the score, the better the hip joint function. Scores within 80 to 89 were categorized as good, those within 70 to 79 as fair, and those ≤69 as poor. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.865.

-

(5)

Noise measurement: A noise meter (TRSI, Suzhou, China) was placed at the center of each ward to effectively capture ambient noise levels. Noise levels were measured continuously over a 24-hour period to account for variations throughout the day. Measurements were conducted on weekdays and weekends to determine comprehensive noise characteristics. The noise meter recorded sound pressure levels (dB) at 1-minute intervals. The readings were stored in the device’s memory and can be downloaded for analysis. The daily noise level for each ward was calculated as the average of all 1-minute interval measurements collected over a 24-hour period. Monthly recalibration of the noise meter was performed to account for any potential drifts in accuracy. Calibration logs were maintained to document each calibration event and ensure traceability. In this study, the average noise level from March 2021 to January 2022 represented the noise level of the control group, and that from February 2022 to January 2023 indicated the noise level of the observation group.

Statistical Processing

SPSS data processing software (Version 25.0.IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used to analyze the collected data. The statistical data were represented by n (%), and the χ2 test was adopted. A normality test using the Shapiro–Wilk test was performed. The measurement data that conformed to normal distribution were expressed by (x̄±s) and analyzed via t-test. A significance level of P < 0.05 was deemed statistically meaningful. Microsoft Excel 2016 software (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA) was used to create figures.

RESULTS

Comparative Analysis of General Information of Each Group

No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of age, sex, body mass index, educational level, average monthly household income, types of disease, and type of prosthesis (P > 0.05). The observation group exhibited a significantly lower noise level than the control group (P < 0.05). Table 1 provides the corresponding details.

Table 1.

Comparison of General Information in Each Group.

| Clinical Data | Control Group (n = 85) | Observation Group (n = 75) | χ2/t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, x̄±s) | 66.34 ± 3.23 | 67.11 ± 3.75 | −0.741 | 0.459 |

| Sex (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 36 (42.35) | 31 (41.33) | 0.017 | 0.896 |

| Female | 49 (57.65) | 44 (58.67) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2, x̄±s) | 22.88 ± 2.09 | 22.76 ± 2.28 | 0.729 | 0.347 |

| Educational level (n, %) | ||||

| High school and below | 28 (32.94) | 32 (42.67) | 1.608 | 0.205 |

| College degree or above | 57 (67.06) | 43 (57.33) | ||

| Average monthly household income, RMB (n, %) | ||||

| 0–4999 | 34 (40.00) | 30 (40.00) | 0.327 | 0.849 |

| 5000–9999 | 41 (48.24) | 34 (45.33) | ||

| ≥10,000 | 10 (11.76) | 11 (14.67) | ||

| Types of disease | 0.286 | 0.866 | ||

| Necrosis of the femoral head | 54 (63.53) | 47 (62.67) | ||

| Femoral head fracture | 26 (30.59) | 22 (29.33) | ||

| Other | 5 (5.88) | 6 (8.00) | ||

| Type of prosthesis (n, %) | 0.068 | 0.794 | ||

| Biological type | 55 (64.71) | 50 (66.67) | ||

| Cement type | 30 (35.29) | 25 (33.33) | ||

| Noise level (dB, x̄±s) | 55.02 ± 6.74 | 42.56 ± 5.64 | 12.5861 | <0.001 |

RMB=Ren Min Bi.

Changes in Self-rating Depression Scale and Self-rating Anxiety Scale Scores of Each Group

Before operation, no difference was observed in the SDS and SAS of each group (P > 0.05). However, 7 days after operation, the observation group showed a lower SAS score than the control group (P < 0.05), and the SAS score at 7 days after operation was lower than that before. Table 2 provides the corresponding details.

Table 2.

Changes in Self-rating Depression Scale and Self-rating Anxiety Scale Scores of Each Group.

| Group | SDS |

SAS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 7 Days after Operation | Preoperative | 7 Days after Operation | |

| Control group (n = 85) | 49.88 ± 4.30 | 50.05 ± 4.83 | 50.33 ± 3.93 | 45.10 ± 4.01* |

| Observation group (n = 75) | 50.15 ± 4.24 | 50.02 ± 4.36 | 51.14 ± 3.86 | 40.45 ± 3.97* |

| t | 0.400 | 0.041 | 1.312 | 7.354 |

| P | 0.691 | 0.967 | 0.192 | <0.001 |

SAS = Self-rating Anxiety Scale, SDS = Self-rating Depression Scale. *P < 0.05 for 7 days postoperatively compared with preoperative.

Changes in Generic Quality of Life Inventory-74 Scores of Each Group

No significant difference in GQOLI-74 was observed between the groups before operation (P > 0.05). On the seventh day after the operation, the observation group achieved a higher score on the “social function” dimension of GQOLI-74 than that in the control group (P < 0.05), and the scores on the “social function” dimension of the two groups after the operation were lower than those before the operation. Table 3 provides the corresponding details.

Table 3.

Changes in Generic Quality of Life Inventory-74 Scores of Each Group.

| Group | Material Life |

Social Function |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 7 Days after Operation | Preoperative | 7 Days after Operation | |

| Control group (n = 85) | 62.85 ± 7.15 | 53.18 ± 5.76* | 53.48 ± 6.23 | 41.77 ± 4.92* |

| Observation group (n = 75) | 63.05 ± 7.25 | 52.91 ± 6.20* | 53.75 ± 4.54 | 43.96 ± 5.38* |

| t | 0.124 | 0.286 | 0.222 | 2.689 |

| P | 0.902 | 0.776 | 0.825 | 0.008 |

P < 0.05 for 7 days postoperatively compared with preoperative.

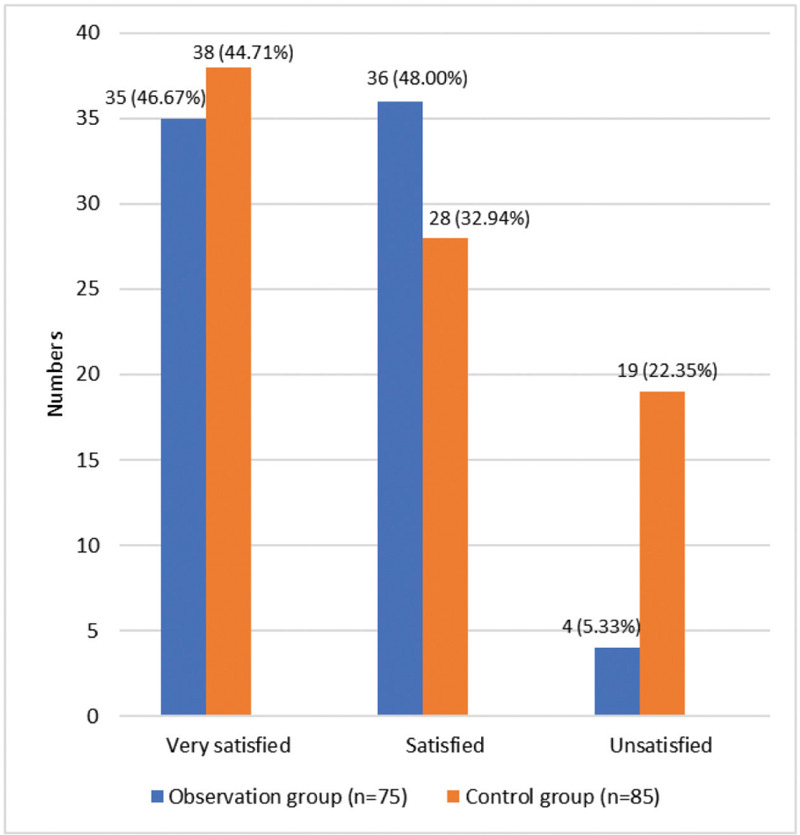

Comparison of Satisfaction among Groups

The satisfaction in the observation group reached 94.67%, compared to 77.65% in the control group, and the disparity between the two groups reached statistical significance (χ2 = 5.165, P < 0.05). Figure 1 shows the specific distribution of patient satisfaction in the two groups.

Figure 1.

Satisfaction of the two groups.

Changes in Harris Hip Score at Various Time Points between the Two Groups

No significant difference was observed in the HHS between the two groups before and after the operation (P > 0.05). However, the HHS of the two groups at 7 days after the operation were higher than those before (P < 0.05). Table 4 provides the corresponding details.

Table 4.

Changes in Harris Hip Scores of Each Group.

| Group | Preoperative | 7 Days after Operation |

|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 85) | 28.67 ± 7.21 | 57.19 ± 11.23* |

| Observation group (n = 75) | 29.14 ± 7.56 | 57.85 ± 12.01* |

| t | 0.402 | 0.359 |

| P | 0.688 | 0.720 |

P < 0.05 for 7 days postoperatively compared with preoperative.

DISCUSSION

After total hip arthroplasty of the elderly, the observation group with ward noise management exhibited a range of positive effects within 7 days after the operation. Firstly, compared with the control group, the observation group exhibited a significantly lower SAS score at 7 days after the operation. Secondly, the observation group attained a significantly higher score on the “social function’ dimension in GQOLI-74 than the control group 7 days after the operation. In addition, the observation group presented a significantly higher satisfaction than the control group. Although no significant differences were observed in hip function (HHS), overall, the combined effect of ward noise management after total hip arthroplasty in the elderly was positive.

At 7 days after the operation, the observation group showed a significantly lower SAS score than in the control group (P < 0.05), which suggests the positive effect of ward noise management on anxiety levels among elderly individuals following total hip arthroplasty. According to studies, anxiety is closely related to noise levels during operation. High levels of noise may increase anxiety levels, and notably, environmental management measures, such as noise reduction, can reduce patients’ anxiety to a certain degree.[14,15,16,17] This condition also suggests that in elderly patients, ward noise management may become a crucial strategy for the alleviation of postoperative anxiety. Stimulus in the form of noise may disrupt the brain’s internal emotional regulation mechanisms, which affect regions, such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, associated with emotion regulation.[18] This disruption can lead to imbalanced levels in neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin,[19] which consequently increases the occurrence and persistence of anxiety. A high-noise environment negatively affects sleep quality,[20] which led to difficulties in falling asleep, sleep interruptions, and decreased sleep quality. Sleep disturbances form a close association with anxiety[21] because inadequate sleep can impair the brain’s emotional regulation function and promote the generation of anxiety emotions. After the reduction of noise exposure, the patient’s anxiety levels decreased considerably, possibly due to the improved sleep quality resulting from reduced noise and decreased environmental stimulation, which led to reduced anxiety.

Lower SAS scores were observed 7 days after the operation than before (P < 0.05). The decrease in the anxiety level at 7 days after the operation may reflect the adaptation process of the elderly patients after the procedure. Preoperative anxiety is a common phenomenon, and initial postoperative anxiety is often associated with uncertainty, worry before operation, and a sense of hesitation regarding postoperative recovery.[22,23] As the rehabilitation process after the operation advances, patients may gradually adapt to their postoperative state and gain a clear understanding of the surgical outcomes and progress of rehabilitation, which would reduce their anxiety levels. In addition, this result may be positively affected by the care of medical staff, family support, and other factors.

The observation and control groups showed significantly higher HHS at 7 days after the operation than those before. However, no significant difference was observed between the two groups (P > 0.05). This finding suggests that ward noise management may have an insignificant effect on hip function recovery. Regardless, interpretation of this result requires caution, and its possible relation to factors, such as small sample size and observation in a short period, should be determined. Future studies should consider increasing the sample size and extending the follow-up period to assess more fully the potential effect of ward noise management on hip function.

The improvement in HHS at 7 days after the operation may be related to the effectiveness of physiological rehabilitation and rehabilitation programs after the procedure.[24] In the early period after the operation, the physiological changes, such as reduction of inflammation, healing of wounds, etc., experienced by patients may contribute to an improved joint function.

At 7 days after the operation, the observation group exhibited a higher score on the “social function” dimension in GQOLI-74 compared with the control group (P < 0.05), while the scores of the “social function” dimensions were lower than those before operation (P < 0.05). These findings imply the positive influence of ward noise management on the quality of life, especially in terms of social functioning, of elderly patients after total hip arthroplasty. This finding is consistent with previous results indicating the possible association of high noise levels with a low quality of life.[25,26] Through reduction of noise exposure, patients experience reduced psychological stress and improved mood, which enhances their quality of life. Particularly, the improvement in social functioning may stem from noise management, which reduces the communication barriers between patients, healthcare professionals, and family members and thus facilitates smooth social interactions. The decreased scores on the “social functioning” dimension 7 days after the operation may be related to the adjustment in life and limited social functioning during the recovery period.

The observation group exhibited significantly higher satisfaction than the control group, which indicates that ward noise management received positive feedback from elderly patients after total hip arthroplasty. This result is in line with previous findings showing that environmental management practices, especially noise reduction practices, may be strongly associated with satisfaction.[27] This outcome can be attributed to patients’ notion regarding their hospital prioritizing their comfort and rehabilitation environment, which prompted them to provide higher evaluation scores on medical services.

This study is a retrospective analysis and thus may involve confounding factors. Nevertheless, baseline data from the two patient groups indicate comparability. The findings of this study were derived from validated scales and lacked laboratory indicators. The limitations should be considered during the interpretation of results. In the future, longitudinal study designs with extended follow-up periods can be conducted to address these limitations and provide comprehensive data and in-depth analysis.

CONCLUSION

This retrospective analysis highlighted the significant positive effects of ward noise management on elderly patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Through the reduction of postoperative anxiety, improvement of social functioning, and increase in overall patient satisfaction, ward noise management emerges as a crucial component in the optimization of postoperative care strategies. Despite the inherent limitations in retrospective study designs, such as potential selection bias and reliance on scale-derived outcomes, the findings underscore the value of environmental management interventions in the improvement of patient outcomes. Future research endeavors that use larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods are warranted to validate these findings and further refine postoperative care protocols.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable

Funding Statement

Funding: This research received no external funding.

References

- 1.Wang XD, Lan H, Hu ZX, et al. SuperPATH minimally invasive approach to total hip arthroplasty of femoral neck fractures in the elderly: preliminary clinical results. Orthop Surg. 2020;12:74–85. doi: 10.1111/os.12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melo-Fonseca F, Miranda G, Domingues HS, Pinto IM, Gasik M, Silva FS. Reengineering bone-implant interfaces for improved mechanotransduction and clinical outcomes. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16:1121–38. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-10022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Hunter S, Lee RL, Wang X, Chan SW. Mobile rehabilitation support versus usual care in patients after total hip or knee arthroplasty: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2022;23:553. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zalikha AK, Karabon P, Hajj Hussein I, El-Othmani MM. Anxiety and depression impact on inhospital complications and outcomes after total knee and hip arthroplasty: a propensity score-weighted retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:873–84. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan X, Wang J, Lin Z, Dai W, Shi Z. Depression and anxiety are risk factors for postoperative pain-related symptoms and complications in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawi N, Alazzawi S, Schmitz A, et al. Noise levels during total hip arthroplasty: the silent health hazard. Hip Int. 2020;30:679–83. doi: 10.1177/1120700019842348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gülşen M, Aydingülü N, Arslan S. Physiological and psychological effects of ambient noise in operating room on medical staff. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:847–53. doi: 10.1111/ans.16582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastani F, Kheirollahi N. Comparing the effect of two methods of using ear protective device on pain intensity in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2022;27:346–50. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.Ijnmr_220_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.You S, Xu F, Zhu X, et al. Effect of intraoperative noise on postoperative pain in surgery patients under general anesthesia: evidence from a prospective study and mouse model. Int J Surg. 2023;109:3872–82. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zung WW. A Self-rating Depression Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H. Manual of Psychological Health Assessment Scales. Beijing: Chinese Journal of Psychological Health Press; 1999. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuling EM, Sierevelt IN, van den Bekerom MP, et al. Predictors of functional outcome following femoral neck fractures treated with an arthroplasty: limitations of the Harris Hip Score. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:249–56. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1424-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsend CB, Bravo D, Jones C, Matzon JL, Ilyas AM. Noise-canceling headphones and music decrease intraoperative patient anxiety during wide-awake hand surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2021;3:254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan X. Improving ambulatory surgery environments: the effects on patient preoperative anxiety, perception, and noise. HERD. 2023;16:73–88. doi: 10.1177/19375867221149990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzhambov AM, Lercher P. Road traffic noise exposure and depression/anxiety: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4134. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anam A, Malik IQ, Hameed Z. Comparison of effect of machine muteness to reduce noise anxiety vs regular settings on patient compliance during pan-retinal photocoagulation. J Pak Med Assoc. 2024;74:384–6. doi: 10.47391/JPMA.9181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alinaghipour A, Salami M, Nabavizadeh F. Nanocurcumin substantially alleviates noise stress-induced anxiety-like behavior: the roles of tight junctions and NMDA receptors in the hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2022;432:113975. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2022.113975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pittolo S, Yokoyama S, Willoughby DD, et al. Dopamine activates astrocytes in prefrontal cortex via α1-adrenergic receptors. Cell Rep. 2022;40:111426. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan TC, Wu BS, Lee YT, Lee PH. Effects of personal noise exposure, sleep quality, and burnout on quality of life: an online participation cohort study in Taiwan. Sci Total Environ. 2024;915:169985. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.169985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou F, Li S, Xu H. Insomnia, sleep duration, and risk of anxiety: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:219–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shawahna R, Jaber M, Maqboul I, et al. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety among hospitalized patients in a developing country: a study of associated factors. Perioper Med (Lond) 2023;12:47. doi: 10.1186/s13741-023-00336-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obuchowska I, Konopinska J. Fear and anxiety associated with cataract surgery under local anesthesia in adults: a systematic review. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:781–93. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S314214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao M, Wang Q, Liu T, et al. Effect of Otago exercise programme on limb function recovery in elderly patients with hip arthroplasty for femoral neck fracture [in Chinese] Zhong Nan Da Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022;47:1244–52. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2022.220307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCullagh MC, Xu J, Dickson VV, Tan A, Lusk SL. Noise exposure and quality of life among nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2022;70:207–19. doi: 10.1177/21650799211044365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi E, Bhandari TR, Shrestha N. Social inequality, noise pollution, and quality of life of slum dwellers in Pokhara, Nepal. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2022;77:149–60. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2020.1860880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M, Kang J, Jiao F. A social survey on the noise impact in open-plan working environments in China. Sci Total Environ. 2012;438:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]