Since the dawn of civilization, humans have been fascinated by the cosmos and developed technologies to leverage outer space for useful purposes. The Babylonians founded astronomy to establish calendars for agriculture, ancient Egyptians aligned the Pyramids to the sun and the stars, and sailors have relied on constellations for navigation for centuries. After World War 2, the space race stimulated huge investments into technologies for space exploration, culminating in the moon landing in 1969 (Fig. 1). Today, Mars rovers are still exploring their planet, space tourism is a reality, and astronauts routinely travel to and from the International Space Station (ISS), which has been continuously populated for over 20 y. The ISS serves as a research laboratory for studying mysteries of our universe as well as understanding how humans adapt to life in outer space, which is critical to support potential colonization of other planets. By monitoring astronauts returning from the ISS, we now know that spaceflight has an immense impact on human physiology, including potentially harmful changes to the cardiovascular system (1). However, why and how these changes occur are poorly understood, very challenging to study, and thus difficult to mitigate. In PNAS, Mair and Tsui et al. (2) sought to address some of these challenges by launching engineered human heart tissues, supported by advanced instrumentation, to the ISS.

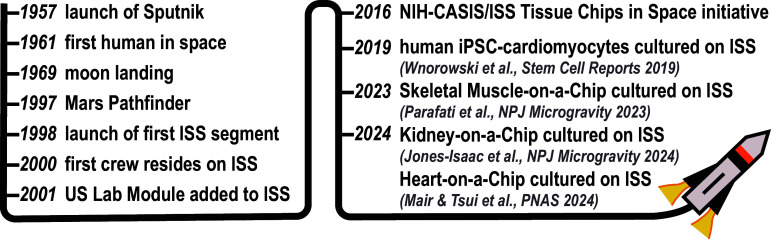

Fig. 1.

Timeline of major milestones in human space exploration (left) and Organ-on-a-Chip experiments onboard the ISS (right).

Historically, the simplest approach to determine the physiological impact of spaceflight has been to simulate microgravity on Earth. For example, hindlimb unloading of mice simulates microgravity and induces bone demineralization, muscle atrophy, and cardiac arrhythmias (3), similar to astronauts (1). Because rodents and humans have inherent differences that limit translation of these studies, human cardiomyocytes have been differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and cultured in clinostat bioreactors that continuously rotate perpendicular to the direction of gravity. Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes cultured in a clinostat generate more reactive oxygen species and have impaired metabolism, calcium flux, and beating frequency (4). Although useful for making some predictions about the effects of microgravity, these approaches are still an artificial representation of true spaceflight and neglect other effects, such as space radiation.

A more authentic (and vastly more complex) approach is to send model organisms to space and then retrieve and evaluate them on Earth. Due to the demands of animal husbandry, simpler model organisms, such as fruit flies and worms, have more commonly been used. For example, fruit flies born on the ISS develop hearts with smaller chambers and lower cardiac output (5). The ISS now has habitats for rodents (6) and mice onboard the ISS experience loss of bone mass and other changes similar to humans (7). However, the capacity for mouse studies on the ISS is limited and, as mentioned above, rodents have limited relevance to humans.

In 2019, human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were first sent to and cultured on the ISS (8). Although cultured cells do not require as much infrastructure or personnel effort as mice, they still require regular media changes and incubators to maintain the proper environment. Thus, these cells were cultured and sealed inside habitats that supported them during their journey to the ISS. Once on the ISS, the cells were cultured in specialized incubators and ISS crew performed weekly media changes. A month later, cells were returned to Earth and found to have altered contraction velocity, calcium handling, and expression of mitochondrial-related genes. Although this initial study was a pioneering accomplishment, one limitation is that cardiomyocytes were cultured as flat, unorganized monolayers, which poorly mimics the aligned, 3-dimensional (3-D) architecture of native cardiac tissue and hinders tissue maturation (9). Furthermore, cells could only be functionally evaluated on Earth within a research lab, using specialized microscopes, and thus, tissue physiology could not be continuously recorded during spaceflight.

Organs-on-Chips induced a paradigm shift in modern biomedical research and are now widely used in both academia and industry for disease modeling and drug screening (10). Organs-on-Chips are engineered microdevices that i) induce human cells to self-assemble into biomimetic tissue constructs, ii) expose engineered tissues to relevant microenvironmental factors, and iii) enable direct readouts of tissue structure and physiology. Organs-on-Chips typically yield tissues that are more mature than conventional cell monolayers and afford more customizability, throughput, and real-time access to living tissues compared to model organisms. Furthermore, Organs-on-Chips are routinely used with human cells and thus are relatively predictive of certain aspects of human biology. Organs-on-Chips also help replace, reduce, and refine animal use in research.

“Mair et al. is a technological feat that showcases how Heart-on-a-Chip systems can be successfully transported to and cultured on the ISS to systematically evaluate how spaceflight impacts human cardiovascular physiology.”

Heart-on-a-Chip models are commonly fabricated by injecting a mixture of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and extracellular matrix into a rectangular mold that contains two flexible pillars. The cells and matrix compact into an elongated, 3-D engineered heart tissue that spans the pillars and rhythmically contracts. Previously, the team of Deok-Ho Kim found that using matrix derived from decellularized pig hearts helps mature engineered heart tissues (11), likely due to the presentation of heart-specific biochemical cues. They also found that doping the matrix with a conductive material (reduced graphene oxide) induces maturation by enhancing the formation of an electromechanical syncytium (11).

Leveraging these advancements, the Kim lab set out to launch their engineered heart tissues to the ISS to systematically measure the effects of spaceflight on human cardiac tissue physiology. However, this is a very ambitious goal due to the specialized infrastructure and personnel typically needed to support Organ-on-Chip experiments. For example, measuring the contractility of engineered heart tissues is usually done by a trained user who images the deflection of flexible pillars on an optical microscope (12), which is not possible onboard the ISS. Thus, the Kim lab partnered with the Sniadecki lab, who previously developed instrumentation for real-time sensing of engineered tissue contractility by embedding magnets in the flexible pillars and sensing pillar deflection with magnetic sensors (13). In this way, the contraction of multiple tissues can be measured in real-time with minimal user intervention. Thus, the team fabricated a sophisticated chamber that included all the electronics for magnetic sensing of contractility from an array of engineered heart tissues and could also be fully sealed for transport to and culture on the ISS. The sealed chamber had a port for media exchanges, which needed to be performed weekly by ISS crew. However, data collection was completely automated and did not require any additional effort from the crew.

These Heart-on-a-Chip systems were then launched to the ISS, cultured for up to 30 d, and returned to Earth. Tissues onboard the ISS became weaker within 12 d and had a more irregular beat-to-beat interval, which is a risk factor for arrhythmias. Additionally, the cytoskeleton was disrupted in spaceflight tissues, consistent with declines in force production, and mitochondria were fragmented and swollen, unlike the healthy networks of mitochondria observed in tissues kept on Earth. The authors also found that several genes and pathways associated with contractility, calcium handling, and mitochondrial function were downregulated in spaceflight tissues, consistent with the structural and functional data, and genes associated with oxidative stress and inflammation were upregulated. Collectively, these data indicate that spaceflight had a deleterious effect on the contractility and metabolism of engineered human heart tissues that was likely triggered by oxidative stress, suggesting that targeting oxidative stress could have therapeutic value for protecting astronauts in the future.

As with all Organ-on-a-Chip models, benchmarking to human data is a critical validation step. In this case, benchmarking is exceptionally challenging since very few people have been in space. Yet, there is some evidence that spaceflight is associated with greater incidence of arrhythmias and cardiac atrophy (14), consistent with the irregular beat-to-beat interval and decline in contractility, respectively, observed in spaceflight Heart-on-a-Chip tissues (2). Select, but not identical, cytokines are also elevated in both engineered heart tissues sent to the ISS (2) and astronauts (15), suggesting that spaceflight triggers immune responses in tissues that are not universally conserved. Thus, more studies are needed to understand the complexities of spaceflight-induced inflammation.

Organ-on-a-Chip models also have caveats that must not be overlooked. Although they are an improvement over cell monolayers, they are still a simplified representation of human tissues and lack many important features present in the body. For example, the Heart-on-a-Chip engineered by Mair and Tsui et al. does not account for changes in cardiac preload, which is especially relevant since central venous pressure decreases in spaceflight (16). The engineered heart tissue is also missing major cell types, such as endothelial and immune cells, which are key players in inflammation and have been integrated in other models (17). Last, the tissues in Mair and Tsui et al. were derived from a single patient and thus the impact of sex, race, and ethnicity is unknown but could be evaluated in future studies by deriving cells from people of diverse backgrounds.

Collectively, the study by Mair and Tsui et al. is a technological feat that showcases how Heart-on-a-Chip systems can be successfully transported to and cultured on the ISS to systematically measure how spaceflight impacts human cardiovascular physiology. Organ-on-a-Chip models of skeletal muscle (18) and kidney (19) have similarly been launched and cultured on the ISS (Fig. 1). These studies were only possible because of the advanced instrumentation that was developed to simultaneously maintain the viability of engineered tissues and automate data collection during spaceflight to minimize demands on the ISS crew. The funding for these and similar projects comes largely from the Tissue Chips in Space initiative, a partnership between the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the NIH and the ISS US National Laboratory (20). Thus, we expect to see more Organ-on-a-Chip systems soon launching into orbit, which will help bring long-term space travel and habitation by humans closer to reality.

Acknowledgments

M.L.M. is supported by NIH R01 HL153286, NIH R01 MH136351, NSF RECODE 2034495, NSF CAREER 1944734, and grant 2023-332386 from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Donor-Advised Fund, an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

Author contributions

M.L.M. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

M.L.M. is an inventor on US Patent No. US9857356B2 by Harvard University and licensed to Emulate, Inc.

Footnotes

See companion article, “Spaceflight-induced contractile and mitochondrial dysfunction in an automated heart-on-a-chip platform,” 10.1073/pnas.2404644121.

References

- 1.Vernice N. A., Meydan C., Afshinnekoo E., Mason C. E., Long-term spaceflight and the cardiovascular system. Precis. Clin. Med. 3, 284–291 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mair D. B., et al. , Spaceflight-induced contractile and mitochondrial dysfunction in an automated heart-on-a-chip platform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Respress J. L., et al. , Long-term simulated microgravity causes cardiac RyR2 phosphorylation and arrhythmias in mice. Int. J. Cardiol. 176, 994–1000 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acharya A., et al. , Microgravity-induced stress mechanisms in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. iScience 25, 104577 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walls S., et al. , Prolonged exposure to microgravity reduces cardiac contractility and initiates remodeling in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 33, 108445 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronca A. E., et al. , Behavior of mice aboard the International Space Station. Sci. Rep. 9, 4717 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maupin K. A., et al. , Skeletal adaptations in young male mice after 4 weeks aboard the International Space Station. NPJ Microgravity 5, 21 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wnorowski A., et al. , Effects of spaceflight on human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte structure and function. Stem Cell Rep. 13, 960–969 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X., Pabon L., Murry C. E., Engineering adolescence: Maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 114, 511–523 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low L. A., Mummery C., Berridge B. R., Austin C. P., Tagle D. A., Organs-on-Chips: Into the next decade. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 345–361 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsui J. H., et al. , Tunable electroconductive decellularized extracellular matrix hydrogels for engineering human cardiac microphysiological systems. Biomaterials 272, 120764 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y., et al. , A platform for generation of chamber-specific cardiac tissues and disease modeling. Cell 176, 913–927.e18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bielawski K. S., Leonard A., Bhandari S., Murry C. E., Sniadecki N. J., Real-time force and frequency analysis of engineered human heart tissue derived from induced pluripotent stem cells using magnetic sensing. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 22, 932–940 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen M., Frishman W. H., Effects of spaceflight on cardiovascular physiology and health. Cardiol. Rev. 27, 122–126 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J., et al. , Single-cell multi-ome and immune profiles of the Inspiration4 crew reveal conserved, cell-type, and sex-specific responses to spaceflight. Nat. Commun. 15, 4954 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckey J. C. Jr., et al. , Central venous pressure in space. J. Appl. Physiol. 81, 19–25 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landau S., et al. , Primitive macrophages enable long-term vascularization of human heart-on-a-chip platforms. Cell Stem Cell 31, 1222–1238.e10 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parafati M., et al. , Human skeletal muscle tissue chip autonomous payload reveals changes in fiber type and metabolic gene expression due to spaceflight. NPJ Microgravity 9, 77 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones-Isaac K. A., et al. , Development of a kidney microphysiological system hardware platform for microgravity studies. NPJ Microgravity 10, 54 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mu X., et al. , Small tissue chips with big opportunities for space medicine. Life Sci. Space Res. (Amst) 35, 150–157 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]