Abstract

Satisfactory reduction of some displaced pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures is not achievable via closed reduction, thus necessitating open procedure, which increases the incidence of complications. Using percutaneous prying-up technique to assist closed reduction may reduce the requirement for transform to an open operation. We retrospectively reviewed displaced pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures treated by the same surgeon from September 2021 to January 2024,with 134 subjects meeting criteria for inclusion. These children were divided into two groups. In Group A(n = 61),the prying-up technique was used to assist with closed reduction of fractures. Group B(n = 73) included fractures treated with conventional manual traction. To balance group size,12 fractures from group A were randomly removed, leaving a final 61 patients in each group. Demographics, operative time, the rate of failed closed reduction, complications and radiographic results were analyzed. The operative time was significantly less in Group A as compared with Group B(mean difference, − 7.22; [95% confidence interval (CI), − 8.49 to − 5.94]; p < 0.001). The rate of failed closed reduction were significantly lower in Group A as compared to Group B(2 of 61 vs. 10 of 61, p = 0.015).

However, we found no difference in terms of the radiographic results and complications between the two groups(p > 0.05). percutaneous prying-up technique significantly improves the efficiency of surgery and reduces rate of failed closed reduction of supracondylar humeral fractures in pediatric patients. Level III, retrospective comparative study.See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Subject terms: Trauma, Paediatric research, Therapeutics

Introduction

Pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures are characteized by a snap in the weak area of bone between the coronoid and the olecranon fossae1–4. Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, introduced by Swenson in 19485,is the most accepted method for displaced(Gartland6 Types II and III, Type II: The distal end of the fracture is backward, or there is transverse displacement at the same time, and the posterior cortex is still in contact. Type III: The broken end of the fracture is completely displaced without contact with the bone cortex.) humeral supracondylar fracture without neurovascular injury7–10.

Content reduction is the precondition for satisfactory outcome of therapy. Due to the sophisticated nature of supracondylar fractures and the lack of skill of surgeons, acceptable reduction is not always achievable through closed manipulation11,12.When closed reduction fails to achieve satisfactory alignment, it is necessary to convert to open surgery for reduction. Open reduction is often accompanied by an increase in complications, such as elbow stiffness, skin scars, and iatrogenic vascular and nerve injuries13–15,9,16.

To increase the success ratio of closed reduction of supracondylar fracture of humerus, doctors had explored some techniques.They generally used a K-wire or Schanz pin as a joystick to assist in manipulation of the humeral to attain fracture closed reduction17–20. Parmaksizoglu et al.18 introduced a joystick technique in which a Kirschner wire was placed laterally to medially under the deltoid muscle in the shaft of the humerus.Mary A Herzog et al.19 assisted fracture reduction by inserting a Schanz pin in the distal humerus from posterior to anterior. The differences between their skills and our technique are the location of pin placement and control method.

On the basis of the previous research, we describe a alternative technology to aid in the closed reduction of displaced pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. We determined whether (1)implementation of prying-up technique decreased the rate of failed closed reduction, (2) decreased the operative time with the prying-up technique, (3) avoided adverse final radiographic alignment and complications.

Materials and methods

Study designs

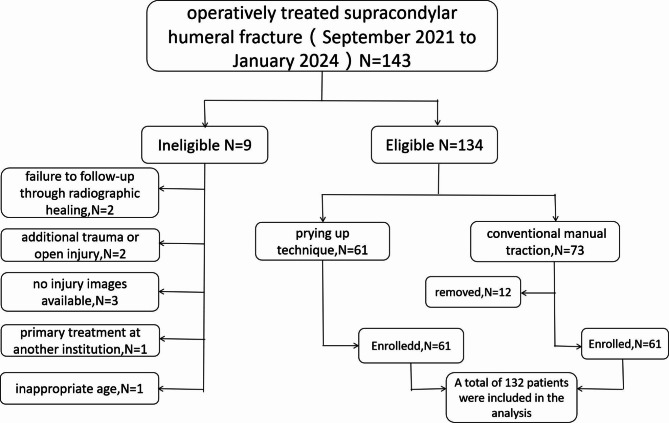

We retrospectively identified 143 displaced (Gartland Types II and III) pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures treated surgically from September 2021 to January 2024. We excluded 9 patients for the following reasons: failure to follow-up through radiographic healing (two), additional trauma or open injury (two), no injury images available (three), primary treatment at another institution (one), and inappropriate age (one).These exclusions left 134 pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures for study.These 134 patients were divided into two groups according to different reduction methods: group A (prying up technique,61 cases) and group B (conventional manual traction,73 cases).To balance the differences between groups, we randomly removed 12 individuals from group B, leaving 122 patients with 61 in each group(Fig. 1). No Children were recalled designedly for this research; all data were acquired from medical records and radiographs. This is a retrospective study, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was carried out in compliance with the STROBE guidelines21. The ethics committee of the Shenzhen Pingle Orthopedic Hospital(file number AF-HEC-034-01.1) approved this registry.The data are anonymous, and the requirement for informed consent was therefore waived.

Fig. 1.

Summary of enrollment, technical roadmap for the retrospective study.

Patients

All the children attending in the Emergency Department or, in the Outpatient Department of Orthopaedics in our institution between September 2021 to January 2024 with supracondylar fractures of the humerus were enrolled in current research if they had the following inclusion criterias: (i) age between two and fourteen years (ii) Unilateral fracture (iii) Closed and extension type fracture (iv) Displaced Gartland6 type II and type III (v) presenting in one week after the injury (vi) no other associated injury and no previous fracture in the same limb.

Patients were excluded if they met the following exclusion criterias: (i) Age less than two years or, greater than fourteen years (ii) Bilateral fracture (iii) Flexion type (iv) Stable Gartland6 type I (v) presenting more than one week after the injury (vi) associated injury in the same limb (vii) Previous fracture in the same limb (viii) Open injuries and pathological fracture (ix) Patients with open reduction (x) Confirmed other vital organs injury (xi) accompanied with neurovascular injury. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in preoperative indexes. The patient demographics data and clinical characteristics were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data and clinical characteristics.

| Group A | Group B | P value | Test Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* (yr) | 6.90 ± 3.42 | 6.80 ± 2.84 | 0.069 | −0.173 |

| Sex(percentage of patients) | 0.277 | 1.181 | ||

| Male | 33(54%) | 28(46%) | ||

| Female | 27(44%) | 34(56%) | ||

| Time from initial injury to surgery (percentage of patients) | 0.758 | 0.554 | ||

| < 24 h | 49(80%) | 46(75%) | ||

| 24 to 48 h | 8(13%) | 9(15%) | ||

| > 48 h | 4(7%) | 6(10%) | ||

| Weight* (kg) | 34.05 ± 6.48 | 32.37 ± 5.86 | 0.268 | 1.509 |

| Fracture side | 0.352 | 0.865 | ||

| Left | 26(43%) | 21(34%) | ||

| Right | 35(57%) | 40(66%) | ||

*The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

Treatments

Surgery was done under general anesthesia. All the subjects were positioned supine on a operating table and closed reduction were executed under the fluoroscopic guidance. Intraoperative radiographs acquired after pin placement was accepted in all samples.Group B was treated with traditional closed reduction, and group A was treated with percutaneous poking technique to assist closed reduction. Transcutaneous steel pin fixation and postoperative treatments in both groups were identical. After surgery, the patients’ injured limbs was encased in a long arm plaster with the forearm in neutral position and the elbow bent to 90 degree.

The sequence of closed reduction was as follows: (1) The surgeon and assistant held the patient’s upper arm and forearm, respectively, and performed homeopathic axial traction. (2) Varus or valgus displacement in the coronal plane was corrected. (3) The sagittal hyperextension deformity or overlap deformity was corrected. (4) The reduction was finally slightly adjusted by pronation or supination of the forearm. The criteria for successful reduction were: (1) the humeral capitellar angle returned to the normal range of 9° to 26° in the anteroposterior view22,23; (2) In the lateral view, the anterior humeral line passed through the middle third of the capitellum.

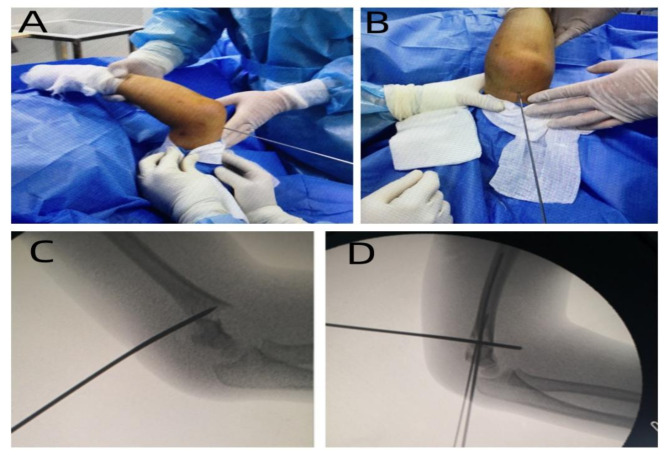

If closed reduction could not be successfully accomplished, the surgeon used the percutaneous prying-up technique to assist. The surgeon touches the location of the fracture directly behind the elbow and percutaneous inserts a 2.5 mm Kirschner wire into the fracture gap. The placement of the Kirschner wire was in the middle of the distal portion of the humeral shaft, avoiding the lateral course of radial nerve. The K-wire was advanced through posterior cortex of humeral, following the fracture line.After the Kirschner wire was successfully inserted, the surgeon sensed the friction of the fracture through the needle body. The anterior and posterior displacement and overlapping displacement of the fracture were reduced by leverage force.Finally, the fracture alignment was well confirmed by intraoperative C-arm machine (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

(A), Lateral view of intraoperative reduction process with “Prying-up technique”. (B), Axial view of intraoperative reduction process with “Prying-up technique”. (C), X-ray fluoroscopy radiograph of intraoperative reduction process with “Prying-up technique”. (D), Immediate postoperative lateral radiograph of “Prying-up technique”showing acceptable reduction.

After the reduction was completed, two or three 1.5 mm diameter anti-rotating steel needle was then inserted diagonally into the contralateral cortex at the high point of the lateral condyle of the humerus. The patient’s elbow was flexed at 90 degrees with the forearm in neutral position, and a cast was used to prevent loss of reduction. (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

(A) After reduction, the anteroposterior radiograph was fixed with Kirschner wire fixation. (B) Lateral view after reduction using fixation with Kirschner wires.

Follow-up and outcome measure

Follow-up evaluation of each subject was done by the same surgeon throughout the research. The patient’s arm was in cast for 3 to 4 weeks, and anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were taken at follow-up to see fracture reduction and alignment. If bridging callus was seen, the Kirschner wire was removed, and gradually strengthen the functional exercise. The patients were followed up again 4 to 6 weeks after removal of the Kirschner wire for reexamination of radiographs and physical examination.

Following messages were recorded as outcome measures: (1) The rate of failed closed reduction. (2) Duration of surgery. (3) Postoperative complications, including iatrogenic fracture, nerve injury, vascular injury, compartment syndrome, wound infection, bone nonunion, etc. (4) Average length of stay(admission to discharge). (5) Flynn’s elbow joint score24(at three months), the Flynn criteria was used to evaluate elbow joint function based on the loss of carrying angle and range of elbow motion(Table 2). (6) Baumann angle(at three months), the angle between the axis of the humeral shaft and the epiphyseal of the capitulum of the humerus, figured on the x-ray film of anteroposterior view of elbow with the approach introduced by Williamson et al.25.

Table 2.

Flynn’s criteria for grading24.

| Outcome | Degree | Carrying angle loss (Degrees) | Total range of elbow motion loss (Degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfactory | Excellent | 0–5 | 0–5 |

| Good | 5–10 | 5–10 | |

| Fair | 10–15 | 10–15 | |

| Unsatisfactory | Poor | Over 15 | Over 15 |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software, version 22.0. The patient’s counting data (sex, postoperative complications and Flynn criteria and fracture side) of the two groups were compared using the Pearson’s chi-square test for non-parametric categorical variables.Independent sample T-test was used to compare measurement data(age, weight, operation time, length of stay and Baumann angle).The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Between September 2021 and January 2024, 134 eligible subjects underwent operative treatment of supracondylar fractures were identified in our hospital. In this crowd, 12 patients were excluded.The 122 patients who were enrolled in the trial were divided into two groups: the “Prying-up technique”group (Group A) (n = 61)and the control group (Group B) (n = 61).There was no significant difference between the two groups at baseline (Table 1).

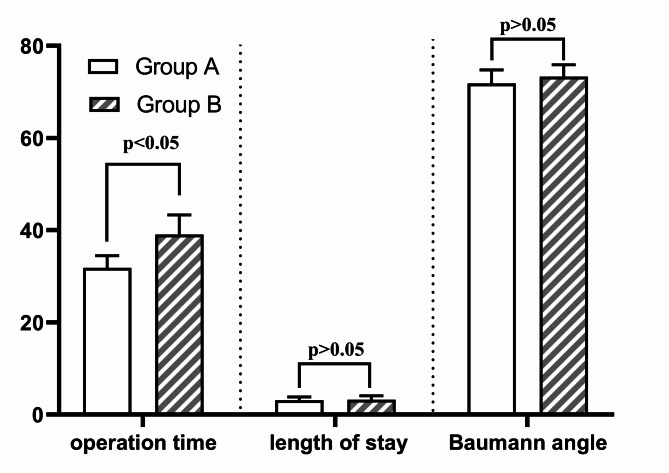

The mean operation time was 31.83 ± 2.62 min in Group A and 39.05 ± 4.27 min in Group B, there was significant increased operation time in Group B (p < 0.001,t = − 11.24). Average length of stay(days) was 3.11 ± 0.73 in group A and 3.21 ± 0.85 in group B, there was no statistical difference between the two groups(p = 0.357,t= − 0.681). There was no significant difference in the Baumann angle at the last follow-up comparison between the A groups(mean, 71.84 ± 2.93) and B Groups(mean, 73.30 ± 2.62 )(p = 0.74, t= − 2.89)(Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Multi-indicator bar chart for each measurement data.The differences of two groups of operation time, length of stay had statistically significance(p < 0.05).There was no difference in Baumann angle between the two groups(p > 0.05).

In group A, closed reduction was successful in 59 cases and 2 cases were converted to open surgery. In group B, 51 cases were successfully reduced by conventional manual traction, and the other 10 cases were conversion to open reduction.There was a significant difference between the two groups in the rate of failed closed replacement (2 of 61 vs. 10 of 61, p = 0.015).

The comparison of Flynn elbow function scores of at last follow-up after operation showed that 47 cases were excellent in group A, 14 cases were good, 43 cases were excellent in group B, and 18 cases were good, with no statistical significance between two groups (p = 0.41).

One patient in group A was found to have radial nerve injury at follow-up,5 patients in group B developed complications, including 2 needle tract infections and 3 iatrogenic peripheral nerve injuries. Iatrogenic fracture, compartment syndrome, deep infection, loss of reduction, implant failure, delayed healing, nonunion were not discovered in the two groups.There was no significant difference between the two groups in complications (1/60 vs. 5/56, P = 0.209).

Discussion

Supracondylar humeral fractures are the most common elbow fractures in children, closed reduction and percutaneous pin fixation is the mainstream treatment for displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children26–32. Although closed reduction has the advantages of less trauma, faster recovery and shorter hospital stay, there is still a risk of failure of reduction and conversion to open surgery, which increases the incidence of complications33–37. Several methods of assisted closed reduction have been reported in the literature, controversy persists among authors regarding optimal methods of closed reduction38–40. Zhu YL38, Li G41 and Novais EN et al.42 used joystick technique. Li Ke et al.43 used traditional manual reduction technique. Herzog MA et al.19 used Schanz pin technique.

“Prying-up technique” has the following advantages. (1) With a short learning curve, junior doctors can quickly master the technique, improving surgical efficiency and success rates. (2) The injury was minor, and the fracture was reduced by steel needle assisted prying. Thus, the soft tissue injury caused by violent means of reduction is avoided, and the destruction of blood circulation and nerve injury are less. (3) The reduction time was fast and accurate, the operation time of doctors was short, and the intraoperative fluoroscopy time of patients was short, which reduces the incidence of postoperative wound infection. (4) “Prying-up technique” exerts less traction, which helps to reduce postoperative pain of patients and reduce swelling of affected limbs while maintaining the stability of fracture reduction.

In this study, Our subjects who received “Prying-up technique” required a signifificantly lower mean operating time than did patients in the control group.We analyzed that “Prying-up technique” can more effectively remove soft tissue insertion, reduce fracture more quickly, and therefore decreased the operation time. In the comparison of reset failure rates, only 2 case in group A failed reduction and converted to open reduction, and the brachialis muscle was found to be trapped at the fracture site after open reduction. Group B failed to reset 10 cases. “Prying-up technique”pays more attention to the protection of soft tissues during the reduction process and reduces the reduction failure caused by muscle pulling, so the reduction success rate is higher.

However, difference between the two groups with regard to Flynn score and Baumann Angle did not reach signifificance.This may be due to the fact that both groups were fixed by kirschner wire and employed the identical functional exercise method. Thus, this clinical difference cannot be directly attributed to the reduction technique but is more likely the result of the fixation method, patient compliance, postoperative functional exercise, or other factors.

The major limitations of the current study were that: (1) this was a retrospective study which recruited only a fraction of patients. To further testify these outcomes, higher quality randomized controlled trials with larger sample size were still required. (2) With the retrospective nature of the study, The completeness of case data is not controlled by trial design, and confounding factors and biases are inevitable. (3) Retrospective studies have limited outcome indicators such as postoperative swelling and pain levels that could not be collected in detail in the medical record. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the prying-up technique improves the postoperative pain profile.

In a word, Our work is certainly important in showing that fractures that are difficult to reduce do not have to be treated openly.For example, Herzog MA et al.19 describe a technique that involves placement of a Schanz pin posteriorly and laterally at the distal end of the humeral shaft, with the needle subsequently used as a joy-stick to aid in reduction and control of deformity in supracondylar humeral fractures in children. The publications by Slongo et al. on the radial fixator show how easy difficult reductions can be made and, above all, how functional follow-up treatment can be carried out without a plaster cast.Their techniques improved the success rate of closed reduction.

Their technique was similar to the prying-up technique we described, except for the placement of the nail and the way the force was applied. Our technique is further away from the radial nerve, and without incision and blunt dissection, it causes less damage to the soft tissue and avoids the possibility of iatrogenic neurovascular injury.

In conclusion, we found that “Prying-up technique” have the advantages of higher chance of success in closed reduction, shorter operative time and less complications.Thus, we recommended the “Prying-up technique” should be chosen to promote closed reduction when the traditional manual method failed to generate admissible reduction.

Author contributions

Author 1 (Zeng): Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing; Author 2 (Wang): Data Curation, Investigation, Writing; Author 3 (Liu): Visualization, Investigation; Review & Editing.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province (Grant Numbers. 20221334).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and The corresponding author will supply the relevant data in response to reasonable requests.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shenzhen Pingle Orthopedic Hospital(Approval no. AF-HEC-034-01.1) and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board (Shenzhen Pingle Orthopedic Hospital) because of the retrospective nature of our study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Omid, R., Choi, P. D. & Skaggs, D. L. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 90(5), 1121–1132 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negrillo-Cárdenas et al. José,Jiménez-Pérez Juan-Roberto,Cañada-Oya Hermenegildo. Automatic detection of landmarks for the analysis of a reduction of supracondylar fractures of the humerus.Med Image Anal, 64 101729. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kropelnicki, A., Ali, A. M., Popat, R. & Sarraf, K. M. Paediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond). 80(6), 312–316 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun, J. et al. Predictive factors for open reduction of flexion-type supracondylar fracture of humerus in children. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23(1), 859 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swenson, A. L. The treatment of supracondylar fractures of the humerus by Kirschner-Wire transfixation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 30, 993–997 (1948). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gartland, J. J. Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 109, 145–154 (1959). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.British Orthopaedic Association Trauma Committee,Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Injury. 52, 376–377. (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sanders James, O. et al. Management of Pediatric Supracondylar Humerus Fractures with Vascular Injury. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 24, e21–e23 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omid, R., Choi, P. D. & Skaggs, D. L. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 90, 1121–1132 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skaggs, D. L. & Flynn, J. M. Supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus In: (eds Beaty, J. H. & Kasser, J. R.) Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Children. 7th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 487–532. (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomori, Y. Nanno M,Takai S.Clinical results of closed versus miniopen reduction with percutaneous pinning for supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children:a retrospective case-control study. Medicine(Baltimore), 97(45), e13162, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kumar Aman,Barik Sitanshu,Raj Vikash. Comment on ‘Which pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures are high risk for conversion to open reduction?‘. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 32, 621 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, T. J. & Sponseller, P. D. Pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J. Hand Surg. Am. 39(11), 2308–2311 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulpuri, K., Hosalkar, H. & Howard, A. AAOS clinical practice guideline: the treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 20(5), 328–330 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shifrin, P. G., Gehring, H. W. & Iglesias, L. J. Open reduction and internal fixation of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Orthop. Clin. North. Am. 7(3), 573–581 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danielsson, L. & Pettersson, H. Open reduction and pin fixation of severely displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Orthop. Scand. 51(2), 249–255 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh, S. W. et al. Minimally invasive surgical techniques for irreducible supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Orthop. 76, 862–866 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parmaksizoglu, A. S., Ozkaya, U., Bilgili, F., Sayin, E. & KabukcuogluY Closed reduction of the pediatric supracondylar humerusfractures: the joystickmethod. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 129, 1225–1231 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzog, M. A., Oliver, S. M., Ringler, J. R., Jones, C. B. & Sietsema, D. L. Pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures: a technique to aid closed reduction. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 471(5), 1419e26 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck, J. D. et al. Mirenda WM.Risk factors for failed closed reduction of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. Orthopedics. 35(10), e1492e6 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 4, e296 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer, K. E., Devito, D. P. & Green, N. E. Comparison of closed reduction and percutaneous pinning versus open reduction and percutaneous pinning in displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J. Orthop. Trauma. 6(4), 407–412 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basaran, S. H. et al. A new joystick technique for unsuccessful closed reduction of supracondylar humeral fractures: minimum trauma. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 25(2), 297–303 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flynn, J. C., Matthews, J. G. & Benoit, R. L. Blind pinning of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Sixteen years’ experience with long-term follow-up. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 56, 263–272 (1974). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williamson, D. M., Coates, C. J., Miller, R. K. & Cole, W. G. Normal characteristics of the Baumann (humerocapitellar) angle: an aid in assessment of supracondylar fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 12, 636–639 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diesselhorst, M. M., Deck, J. W. & Davey, J. P. Compartment syndrome of the upper arm after closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of a supracondylar humerus fracture. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 34(2), e1–4 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao, H. et al. Comparison of lateral entry and crossed entry pinning for pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 16(1), 366 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slobogean, B. L., Jackman, H., Tennant, S., Slobogean, G. P. & Mulpuri, K. Iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury after the surgical treatment of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus: number needed to harm, a systematic review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 30(5), 430–436 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Mulpuri, K. & Wilkins, K. The treatment of displaced supracondylar humerus fractures: evidence-based guideline. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 32(Suppl 2), S143–S152 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edmonds, E. W., Roocroft, J. H. & Mubarak, S. J. Treatment of displaced pediatric supracondylar humerus fracture patterns requiring medial fixation: a reliable and safer cross-pinning technique. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 32(4), 346–351 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brauer, C. A., Lee, B. M., Bae, D. S., Waters, P. M. & Kocher, M. S. A systematic review of medial and lateral entry pinning versus lateral entry pinning for supracondylar fractures of the humerus. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 27(2), 181–186 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ladenhauf, H. N., Schaffert, M. & Bauer, J. The displaced supracondylar humerus fracture: indications for surgery and surgical options: a 2014 update. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 26(1), 64–69 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flood, M. G., Bauer, M. R. & Sullivan, M. P. Radiographic considerations for pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 32(2), 110–116 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hindman, B. W. et al. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus: prediction of the Cubitus varus deformity with CT. Radiology, 168, 513–515. (1988). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Hussein Al-Algawy, A. A., Aliakbar, A. H. & Witwit, I. H. N. Open versus closed reduction and K-wire fixation for displaced supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 29(2), 397–403 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dineen, H. A., Stone, J. & Ostrum, R. F. Closed reduction Percutaneous Pinning of a Pediatric Supracondylar Distal Humerus fracture. J. Orthop. Trauma. 33(Suppl 1), S7–S8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shoaib, M., Hussain, A., Kamran, H. & Ali, J. Outcome of closed reduction and casting in displaced supracondylar fracture of humerus in children. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 15(4), 23–25 (2003). [PubMed]

- 38.Zhu, Y. L., Hu, W., Yu, X. B., Wu, Y. S. & Sun, L. J. A comparative study of two closed reduction methods for pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures. J. Orthop. Sci. 21(5), 609–613 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turgut, A., Aksakal, A. M., Öztürk, A. & Öztaş, S. A new method to correct rotational malalignment for closed reduction and percutaneous pinning in pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 48(5), 611–614 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marson, B. A. et al. Interventions for treating supracondylar elbow fractures in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6(6), CD013609 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, G. et al. Double joystick technique - a modified method facilitates operation of Gartlend type-III supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B25. (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Novais, E. N., Andrade, M. A. & Gomes, D. C. The use of a joystick technique facilitates closed reduction and percutaneous fixation of multidirectionally unstable supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 33(1), 14–19 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Ke, C. & Xing, W. Xingquan et al. Clinical observation on the treatment of supracondylar fracture of humerus in children with traditional Chinese medicine manual reduction. J. Practical Chin. Med., 39(04), 783–784, (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript and The corresponding author will supply the relevant data in response to reasonable requests.