Abstract

This study presents a case of penetrating craniocerebral injury resulting from a nail gun accident, which is a rare etiology for penetrating brain injuries. Immediate surgical intervention is crucial to mitigate the risk of infection. The patient was a 28-year-old male who underwent craniotomy for foreign body extraction and debridement following presentation. Preoperative imaging aided in the precise localization of the injury, and guided the surgical approach. The surgical technique focused on minimizing brain tissue manipulation to prevent further damage. Postoperative care included prophylactic antibiotics and antiseizure medications. No neurological deficits or signs of infection were found on follow-up examination. Nail gun-related injuries are rare; in this case, prompt surgical intervention and meticulous postoperative care contributed to favorable outcomes, emphasizing the importance of timely management in such cases.

Keywords: Injuries, Penetrating brain injuries, Neurosurgical procedures, Wounds

INTRODUCTION

Penetrating brain injuries can result from both missile and nonmissile sources. Although non-missile penetrating brain injuries are less frequent, they commonly exhibit more favorable outcomes because of their localized nature.13) Penetrating injuries caused by nail gun accidents are rare, with incidents reported significantly less frequently than other forms of penetrating injuries.2,19) However, since the widespread adoption of nail guns in 1959, the incidence of such injuries has increased slightly.19) Immediate surgical intervention involving foreign body extraction and debridement is imperative to mitigate the risk of infection.

In this report, we present the case of a male patient who experienced a penetrating craniocerebral injury due to a nail gun accident. In this report, we provide a detailed account of this case, including the surgical techniques employed, and discuss it in the context of the existing literature.

CASE REPORT

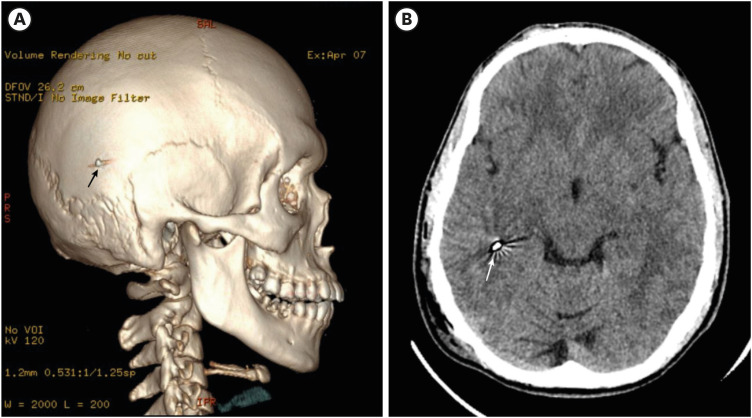

A 28-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a complaint of right-sided headache following accidental injury involving a nail gun 2 hours prior. The patient denied experiencing any loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, or motor or sensory abnormalities. The patient had a history of complete primary tetanus vaccination. Physical examination revealed an entry wound in the right temporo-occipital area measuring approximately 0.4 cm in diameter, with no associated exit wound (FIGURE 1). Computed tomography (CT) revealed a hyperdense metallic lesion, with the proximal tip lodged in the inferolateral part of the right parietal bone, and the distal tip extending into the subcortical region of the right temporal lobe (FIGURE 2). No signs of intracranial hemorrhage were observed. The patient was immediately administered human tetanus immunoglobulin via injection, and was promptly scheduled for surgical removal of the foreign body, followed by debridement of the surrounding tissue.

FIGURE 1. The entry wound in the right temporooccipital area, measuring approximately 0.4 cm in diameter.

FIGURE 2. Supportive examination. (A) The 3-dimensional reconstruction revealing the proximal tip of the nail (black arrow) situated in the inferolateral aspect of the right parietal bone. (B) The brain window of the computed tomography scan shows the distal tip (white arrow) lodged within the right temporal lobe.

Operative technique

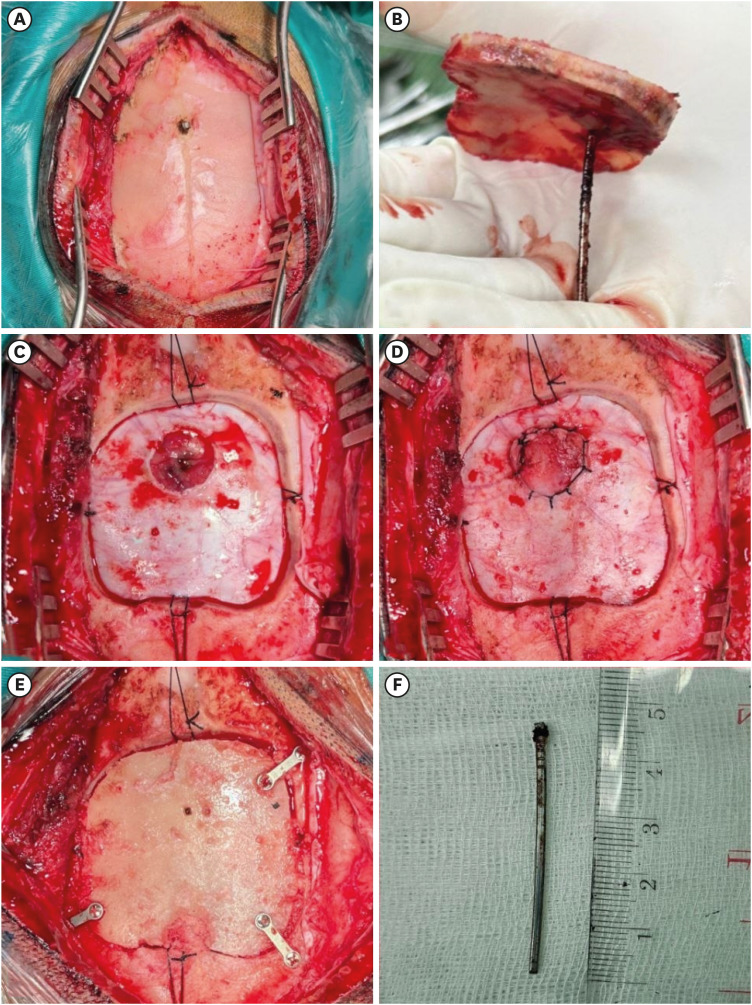

The patient underwent craniotomy to extract the foreign body, with concurrent debridement (FIGURE 3). The patient was placed in the park bench position. A linear incision was made in the right temporo-occipital area, layer-by-layer, until the bone was reached. The proximal part of the nail gun was embedded into the inferolateral aspect of the right parietal bone (FIGURE 3A). A craniotomy was performed around the nail in which careful elevation of the constructed bone flap facilitated the removal of the embedded nail along with the bone (FIGURE 3B). The extracted nail was 4.5 cm in length and approximately 0.2 cm in diameter (FIGURE 3F). Durotomy was performed around the nail entry site, followed by meticulous hemostasis (FIGURE 3C). Debridement was further performed to remove the necrotic tissue surrounding the wound, followed by cleansing of the affected brain parenchyma and bone with gentamicin antibiotic solution. Subsequently, duroplasty was performed in which the dura was closed using a watertight technique (FIGURE 3D). The patient's bone was finally secured with plates and screws (FIGURE 3E), and the incision was closed layer-by-layer. The duration of the surgery was 2 hours.

FIGURE 3. The step-by-step surgical procedure. (A) The proximal tip of the nail is visible embedded in the parietal bone. (B) The bone flap and nail are simultaneously removed. (C) Durotomy is performed around the nail site, followed by sufficient debridement of the cortex. (D) Duroplasty and (E) cranioplasty are carried out. (F) The dimensions of the nail are measured to be 4.5 cm in length and 0.2 cm in width.

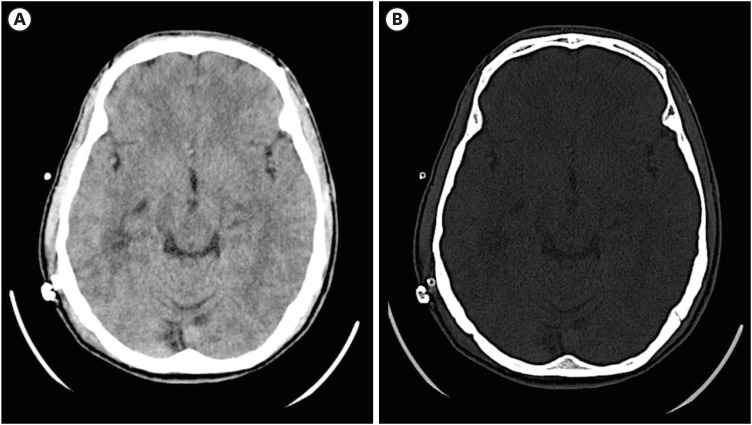

The patient was monitored and managed in the ward for 3 days, during which no neurological deficits, such as visual field disturbances or seizures, were observed. A repeat CT scan performed 3 days later revealed no remaining fragments in the intracranial cavity, although a slight perifocal edema was noted around the original nail site (FIGURE 4). Phenytoin, was administered for 7 days at a dosage of 100 mg every 8 hours, as prophylactic anti-seizure therapy. Subsequent routine follow-up examinations at 3 months and 1 year revealed no neurological deficits, and the patient resumed normal activity without impairment.

FIGURE 4. The follow-up computed tomography scan shows no remaining nail or bone fragments around the surgical site, as seen in both the axial view (A) brain window and (B) bone window.

DISCUSSION

Penetrating brain injuries can be caused by both missile and nonmissile sources. Although their prevalence is lower than that of closed-head injuries, these injuries have a significantly worse prognosis. Non-missile penetrating brain injuries are less common, but have better outcomes owing to their localized nature.9,13) Preoperative workup is crucial to accurately determine the location of the foreign body, and the extent of injury to the surrounding area.4,12) In our patient, CT with a bone window and 3-dimensional reconstruction was helpful in preoperative planning, allowing precise localization of the foreign body as well as identification of the best approach for lesion removal. Considering the suspected metallic nature of the foreign body, skull radiography and CT scans were particularly beneficial. Brain window CT can detect intracranial bleeding, although its utility may be limited in cases involving metallic objects because of potential artifacts. Angiography may be performed in some cases, particularly when the injury is related to the skull base area or when vascular injury is highly suspected.

The surgical technique for stab wounds typically involves extraction of the foreign body via the entry wound. However, in some cases where extraction through the entry wound is not feasible, foreign body extraction may be performed through the exit wound.20) Suring the surgical procedure in our patient, a temporo-occipital craniotomy was performed based on the preoperative localization of the foreign body. We minimized manipulation of the brain tissue beneath to avoid further parenchymal damage and reduce the risk of intracranial bleeding. The evaluation of vascular structures is also important in patients with stab wounds. In the present patient, thorough evaluation revealed no vascular structural injuries or active bleeding during the intraoperative period. However, one limitation of this study was that we did not perform preoperative CT angiography (CTA) due to facility limitations and policies related to CTA at our institution.

Debridement and use of prophylactic antibiotics are common procedures in such cases. Surgical intervention is recommended within 12 hours to minimize the risk of infection.10,11,12,13) In our case, surgery was performed within 3 hours of onset. Given the depth and length of the foreign body tract, debridement was limited to the superficial region to prevent further bleeding or nerve damage that could have been induced by deeper exploration. We further cleaned the bone affected by the embedded nail and performed durotomy around the dural site. The surgical field was cleaned using gentamycin. According to the literature, prophylactic antibiotic use for 6 weeks is necessary to prevent infections. However, infection risks still exist, with infection occurring in 1%–5% of cases in patients administered broad-spectrum antibiotics, compared with the pre-antibiotic era, where the infection risk could reach 58.8%.13,14) In our patient, intravenous antibiotics were administered for 3 days, followed by oral antibiotics for 4 consecutive weeks. No signs of infection were observed during the follow-up. Some studies have further recommended the use of anti-seizure prophylaxis, as seizures occur in 30%–50% of cases. The use of antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin for 7 days is sufficient to prevent seizures, as observed in our patient. Prolonged use beyond 7 days is not recommended.3)

Prophylactic tetanus immunization is mandatory, and should be administered as soon as possible in cases of penetrating brain injury.5,15,16) Several types of wounds are considered to be at particularly high risk of tetanus, including wounds that require operative procedures, but face delays of more than 6 hours; wounds containing foreign objects; wounds in patients with sepsis; and contaminated wounds.5,18) As such, the administration of tetanus prophylaxis should be tailored to the patient's immunization history and wound characteristics. Without intervention, patients with contaminated wounds may develop symptoms of muscle rigidity and spasms within 4–21 days following inoculation.6) The patient in the present case had a complete history of tetanus vaccination during childhood. Consequently, the patient was promptly administered human tetanus immunoglobulin in the emergency unit before undergoing an operative intervention.

In many reported cases, patients experience residual symptoms due to injury or surgical complications.1,7,12) In cases of missile injury, the direct impact effects, in addition to the vibration and velocity of the bullet penetrating the brain, can inflict more damage. Similarly, stab wounds can cause symptoms depending on the area of damage. Depending on the underlying mechanism, cerebrospinal fluid leaks may be common, while operative correction is recommended if the defect does not close spontaneously.8,12,17) Fortunately, our patient did not exhibit any symptoms. Similarly, the patient's neurological function remained intact following surgery. In the present case, no signs of cerebrospinal fluid leakage were observed during the observation or follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Nail gun-related penetrating brain injuries, although rare, require immediate surgical intervention to mitigate risk. Preoperative imaging can guide the precise removal, whereas meticulous debridement reduces the risk of infection. Our patient recovered successfully with no neurological deficits, confirming the importance of prompt treatment and postoperative care protocols. Vigilant follow-up ensures the early detection and management of any potential complications, thus underscoring the importance of comprehensive patient management in achieving favorable outcomes.

Footnotes

Funding: No funding was obtained for this study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethics Approval: Ethics approval is not required because a case report is not considered research at our institution, specifically, Komisi Etik Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Udayana (Udayana University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Commission).

References

- 1.Abdulbaki A, Al-Otaibi F, Almalki A, Alohaly N, Baeesa S. Transorbital craniocerebral occult penetrating injury with cerebral abscess complication. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2012;2012:742186. doi: 10.1155/2012/742186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alain J, Lavergne P, St-Onge M, D’Astous M, Côté S. Bilateral nail gun traumatic brain injury presents as intentional overdose: a case report. CJEM. 2018;20:788–791. doi: 10.1017/cem.2017.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antiseizure prophylaxis for penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51:S41–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anwer M, Kumar A, Kumar A, Kumar D, Ahmed F. Penetrating sugarcane injury to brain via orbit: a case report. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2024;20:52–56. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2024.20.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins S, White J, Ramsay M, Amirthalingam G. The importance of tetanus risk assessment during wound management. IDCases. 2015;2:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duerden BI, Brazier JS. Tetanus and other clostridial diseases. Medicine (Abingdon) 2009;37:638–640. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatigba OH, Yarou HB, Quenum K, Hadonou A, Hodé L, Padonou C, et al. Management and prognostic factors of penetrating craniocerebral wounds at one teaching hospital in Benin. Open J Mod Neurosurg. 2020;11:34–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanafi I, Munder E, Ahmad S, Arabhamo I, Alziab S, Badin N, et al. War-related traumatic brain injuries during the Syrian armed conflict in Damascus 2014-2017: a cohort study and a literature review. BMC Emerg Med. 2023;23:35. doi: 10.1186/s12873-023-00799-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawryluk GW, Selph S, Lumba-Brown A, Totten AM, Ghajar J, Aarabi B, et al. Rationale and methods for updated guidelines for the management of penetrating traumatic brain injury. Neurotrauma Rep. 2022;3:240–247. doi: 10.1089/neur.2022.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helling TS, McNabney WK, Whittaker CK, Schultz CC, Watkins M. The role of early surgical intervention in civilian gunshot wounds to the head. J Trauma. 1992;32:398–400. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubschmann O, Shapiro K, Baden M, Shulman K. Craniocerebral gunshot injuries in civilian practice--prognostic criteria and surgical management: experience with 82 cases. J Trauma. 1979;19:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazim SF, Shamim MS, Tahir MZ, Enam SA, Waheed S. Management of penetrating brain injury. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4:395–402. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.83871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampros M, Alexiou G, Sfakianos G, Prodromou N. In: Pediatric neurosurgery for clinicians. Alexiou G, Prodromou N, editors. Berlin: Springer Nature; 2024. Penetrating head trauma; pp. 459–467. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meister MR, Boulter JH, Yabes JM, Sercy E, Shaikh F, Yokoi H, et al. Epidemiology of cranial infections in battlefield-related penetrating and open cranial injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95:S72–S78. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milton J, Rugino A, Narayan K, Karas C, Awuor V. A case-based review of the management of penetrating brain trauma. Cureus. 2017;9:e1342. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyagi K, Shah AK. Tetanus prophylaxis in the management of patients with acute wounds. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:e267–e269. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh JW, Kim SH, Whang K. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leak: diagnosis and management. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2017;13:63–67. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2017.13.2.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UK Health Security Agency. Tetanus: the green book, chapter 30. London: GOV.UK; 2022. [Accessed June 7, 2024]. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/62978bf4e90e070395bb3e0f/Green_Book_on_immunisation_chapter_30_tetanus.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang AS, Zeng MH, Wang F. Successful treatment of a nail gun injury in right parietal region and superior sagittal sinus. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:1297–1301. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardhana DP, Lauren C, Awyono S, Rosyidi RM, Tiffany T, Maliawan S. Particular surgical technique for transorbital-penetrating craniocerebral injury inflicted by a screwdriver: technical case report. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2023;19:356–362. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2023.19.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]