Abstract

Brain ischemia results in the activation of a cascade of inflammatory responses, contributing to the pathogenesis of stroke. This study aimed to assess the patterns of possible changes in the expression of specific inflammation-associated protein-encoding genes and miRNAs in the peripheral blood between the acute and chronic phase of young-onset cryptogenic (Cryp) and large-artery atherosclerotic (LAA) stroke. Blood and serum were collected from patients with cryptogenic and large-artery atherosclerotic stroke at the stroke onset and 1-year follow-up. The relative expression of inflammation-related genes was analysed at the mRNA and miRNA levels using real-time quantitative PCR. Moreover, the relationship between the relative gene expression levels and clinical data was assessed using several different statistical approaches. Seventy-three patients were included in this study, with a median age of 47 (IQR, 9) years. Approximately 72% were men. In patients with cryptogenic stroke, at the mRNA level, ICAM1, CXCL8, TNF, NFKBIA, PYCARD, IL1B, and IL18 were observed to be upregulated at the stroke onset compared to the 1-year follow-up. In patients with LAA stroke, only the expression of NFKBIA was significantly higher during acute stroke. Further, the miRNA serum levels of miR-21, miR-122, and miR-155 were higher at the onset of stroke in patients with cryptogenic stroke but not in those with LAA stroke. The differences between the relative gene expression levels during acute stroke and at the 1-year follow-up were more pronounced in patients with cryptogenic stroke with no cardiovascular risk factors. The expression changes of inflammatory genes in whole blood and miRNAs in the serum differ in patients with cryptogenic and LAA stroke.

Subject terms: Genetics, Neurology

Introduction

Ischemic stroke in young individuals is a rare condition. However, up to 40% of patients are diagnosed with cryptogenic stroke, meaning that the cause of stroke remains unknown1–4.

The occlusion of a blood vessel initiates a cascade of events starting from the brain and further spreading to the entire body to fight for the restoration of normal brain function. Ischemia results in the activation of inflammatory responses both in the brain and in the periphery5. Inflammation can be both protective and damaging; however, it remains unclear which factors determine the balance between tissue damage and repair during and after acute stroke6,7. Several chronic diseases causing systemic inflammation are known to be risk factors for stroke8. This has led to further studies assessing immunomodulatory therapies targeting inflammation in acute stroke9,10. Still, none of these therapies have made it to clinical practice yet.

One approach to understanding stroke pathogenesis is to assess gene expression changes in the brain, blood cells, or serum11,12. For example, distinct gene expression patterns characterise different stroke subtypes13–15. Gene expression-related studies also help to better describe inflammatory processes occurring during stroke. An earlier Swedish study published already in 1999, observed increased mRNA expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8), interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), and interleukin-17 (IL-17) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with acute stroke16. This phenomenon has also been observed at the protein level17. Further studies have used sets of genes specific to acute stroke and/or particular stroke subtypes12,13,18 and have indicated that the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and inflammasome pathways contribute to stroke pathogenesis6,9,19. More specifically, in the early phase of stroke, ischemic brain tissues release damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signals, which induce the activation of NF-κB. This leads to the increased expression of inflammasome components, followed by the activation of the NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome7,19–22. In addition, the activation of NF-κB leads to increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and upregulation of numerous other cellular proteins, including adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1)6,22. In line with this, animal studies have demonstrated that the suppression of the NF-κB signalling has neuroprotective effects in experimental stroke23 and that the inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome may have therapeutic potential in ischemic stroke9,22.

One mechanism in gene expression regulation involves microRNAs (miRNAs), which act at the post-transcriptional level, either initiating mRNA degradation or suppressing translation24. Numerous miRNAs have been reported to be associated with stroke pathogenesis12,25,26 and are also promising biomarkers of stroke25,26. In addition, one can expect that miRNAs involved in the regulation of neuroinflammation and inflammation in general, including miR-146a, miR-155, and miR-21, and those affecting lipoprotein metabolism, such as miR-122, may affect stroke-related processes27–29.

The majority of knowledge regarding the role of inflammation in stroke comes from preclinical research. However, more clinical studies are needed as translational research enables these data to be confirmed and implemented into clinical practice. As stroke in young individuals is often cryptogenic, efforts should be made to understand the factors leading to stroke, including the role of inflammation.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the patterns of possible changes in the expression of specific inflammation-associated protein-encoding genes and miRNAs in the peripheral blood between the acute and chronic phase of young-onset cryptogenic (Cryp) and large-artery atherosclerotic (LAA) stroke. In addition, we studied whether these expression changes are associated with clinical characteristics.

Methods

Patients

The Estonian Young Stroke Registry is a prospective ongoing hospital-based registry of patients with young-onset (≤ 54 years of age) stroke. Patients with ischemic stroke and complete clinical follow-up and biological data have been included in the study. The detailed methods of clinical data collection have been published previously10. All patients have been managed in a comprehensive stroke centre of the university hospital, and the diagnosis of stroke has been made by a stroke neurologist. Stroke subtypes were defined according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria30. Stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Selected patients with cryptogenic and LAA stroke were included in the current sub-study. All patients have signed informed consent. The study protocol has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (license 384/M-21) and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Blood and serum sample collection

For total RNA, 9 ml of peripheral blood was collected during acute stroke (within 72 h from stroke onset, time-point 1) and at 1-year follow-up (time-point 2) using Tempus™ RNA tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and immediately stored at −80 °C until RNA purification analysis. Serum was collected from the same cohort at the same time-points using Vacuette® Z Serum Sep Clot Activator Blood Collection Tube (Greiner Bio-one GmbH, Kremsmünster, Austria) and centrifuged following collection. Then, it was separated and stored at −80 °C until RNA purification.

Total RNA purification and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from whole blood and serum was extracted using Tempus™ Spin RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Serum samples of 150 μl were used for RNA purification. The concentration and purity of RNA was assessed using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For whole blood RNA, the integrity was additionally measured using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For cDNA synthesis from mRNA, 200–500 ng of a total RNA oligo-dT (TAG Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark), RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase, and RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For qPCR, 5× HOT FIREPol EvaGreen qPCR Supermix (Solis BioDyne, Tartu, Estonia) and QuantStudio 12K Flex as the Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used according to manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR primers were designed using Primer 331 and were ordered from TAG Copenhagen (Supplementary Table S1). Target gene expression was normalised to human EEF1A1 using the ΔΔCt calculation. The average expression levels of each gene were equalised with 1.0 at time-point 1. For miRNA RT-qPCR, 5–10 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed using TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed in duplicates using 5× HOT FIREPol® Probe qPCR Mix Plus (ROX) (Solis BioDyne, Tartu, Estonia) and the following TaqMan microRNA assays: hsa-miR-122-5p (ID: 002245), has-miR-155 (ID: 000479), has-miR-21 (ID: 000379), hsa-miR-146a-5p (ID: 000468), and has-let-7a (ID: 000377) (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Relative miRNA levels were normalised to the level of let-7a and calculated according to the ΔΔCt method.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the RT-qPCR results was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 and STATA 17. Data were analysed either using paired two-tailed t-test, ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test or two-way repeated measures ANOVA. The average expression of time-point 1 was set to one in the case of pairwise analysis. When all groups were analysed, the average expression of the values of the cryptogenic stroke samples at time-point 1 was set to 1. The difference of group medians was evaluated using Mann–Whitney U-test and for percentages using Fisher’s test. The differences between the groups were considered significant at p < 0.05.

The relationship of clinical variables with gene expression was assessed using multiple linear regression analysis. The clinical variables used in multiple comparisons of gene expression analysis were age, sex, recent infection (defined as any infection diagnosed 2 weeks before stroke or at the time of admission), hs-CRP value (non-modifiable risk factors), body mass index, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus (modifiable risk factors), and NIHSS score (score 0–4 = mild stroke and score ≥ 5 = severe stroke). The definitions of the included variables have been described previously4.

Results

Patient characteristics

Seventy-three patients were included in this study, with a median age of 47 (IQR, 9) years; 72% were men. Patients with LAA stroke had more cardiovascular risk factors and were significantly older. However, the sex proportions and stroke severity were similar in both groups. The baseline characteristics of the included patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

General clinical characteristics of the study participants.

| Total (N = 73) | Cryptogenic stroke (N = 48) | LAA stroke (N = 25) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 47 (9) | 46 (13.5) | 50 (5) | 0.009 |

| Men, n (%) | 53 (72) | 34 (71) | 19 (76) | 0.78 |

| NIHSS on admission, median (IQR) | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | 4 (4) | 0.94 |

| NIHSS on admission 0–4, n (%) | 40 (55) | 27 (56) | 13 (52) | 0.99 |

| NIHSS at 1 year, median (IQR) | 0 (0.25) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 0.15 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 37 (50) | 20 (42) | 17 (68) | 0.09 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 9 (12) | 4 (8) | 5 (20) | 0.26 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 47 (64) | 27 (56) | 20 (77) | 0.12 |

| Preceding infection, n (%) | 5 (7) | 4 (8) | 1 (4) | 0.65 |

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | 43 (58) | 23 (48) | 20 (80) | 0.03 |

| BMI ≥ 30, n (%) | 24 (33) | 13 (27) | 11 (44) | 0.19 |

| Stroke in 1st degree relative, n (%) | 24 (33) | 11 (23) | 13 (52) | 0.04 |

| hs-CRP on admission, (mg/L) median (IQR) | 2.4 (4.5) | 1.5 (3.7) | 3.3 (3.5) | 0.05 |

| hs-CRP at 1 year, (mg/L) median (IQR) | 1.6 (2.4) | 1.2 (1.9) | 2.7 (2.8) | 0.02 |

IQR interquartile range, n number, LAA large-artery atherosclerosis, NIHSS National Institute of Health Stroke Scale, BMI body mass index, hs-CRP high-sensitive C-reactive protein.

aFisher’s test for percentages, Mann-Whithney U-test for medians.

The expression of inflammation-associated genes were increased in the acute phase of cryptogenic stroke

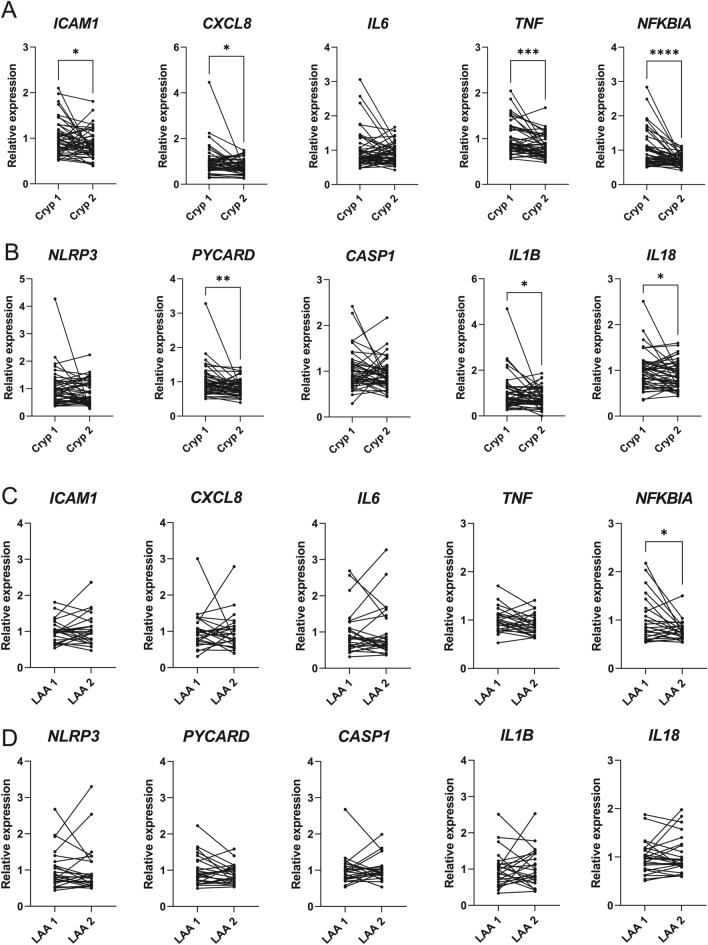

To assess whether there were changes in the expression of inflammation-associated genes in young-onset cryptogenic and LAA stroke, we chose genes regulating inflammation during stroke and/or activated by the NF-κB signalling (ICAM1, CXCL8, IL6, TNF, NFKBIA) or genes from the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (NLRP3, PYCARD, CASP1, IL1B, IL18)6,9,16,17,19–22. In patients with cryptogenic stroke, at the mRNA level, ICAM1, CXCL8, TNF, NFKBIA, PYCARD, IL1B, and IL18 were observed to be significantly upregulated in whole blood in acute stroke compared to the 1-year follow-up (Fig. 1A,B).

Fig. 1.

Multiple inflammation-associated genes were upregulated during cryptogenic (Cryp) stroke but not during large-artery atherosclerotic (LAA) stroke. The relative mRNA expression of the selected genes associated with the NF-κB (A,C) and inflammasome (B,D) pathways was measured using RT-qPCR from whole blood of patients with cryptogenic (Cryp) or LAA stroke immediately after the stroke onset (Cryp 1, LAA 1) or 1 year later (Cryp 2, LAA 2). Paired two-tailed t-test, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

In patients with LAA stroke, the differences in the two time-points followed a similar trend; however, only the expression of NFKBIA was significantly higher during the acute stroke (Fig. 1C,D). When patients with cryptogenic and LAA stroke were compared, the increased levels of ICAM1, CXCL8 and IL1B were detected during the acute cryptogenic stroke compared with the acute phase of LAA stroke. No significant differences in other tested genes were detected between the groups (Supplementary Fig. S1). These data revealed that the expression of multiple genes from the NF-κB and inflammasome pathways would increase immediately after stroke compared to the 1-year follow-up in patients with cryptogenic stroke.

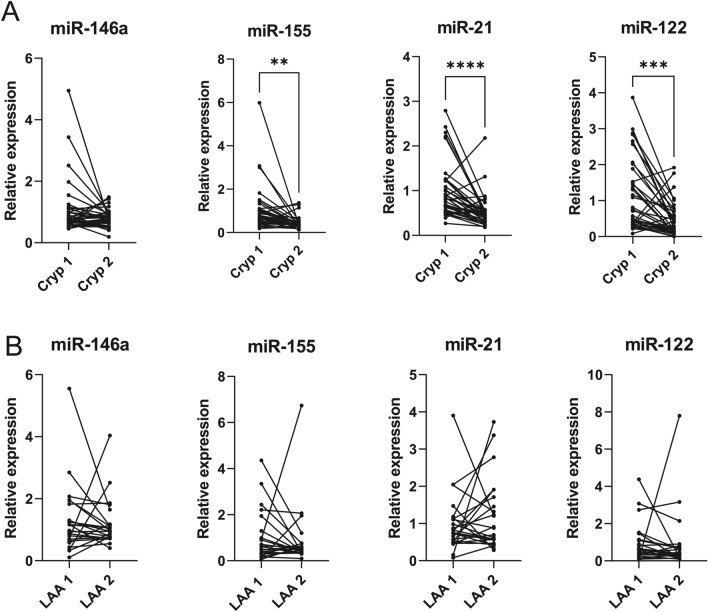

The serum levels of inflammation-associated miRNAs were increased in the acute phase of cryptogenic stroke

The expression of selected miRNAs, which are known to be involved in the regulation of neuroinflammation (miR-146a, miR-155 and miR-21) or affect lipoprotein metabolism (miR-122)27–29,32, was analysed from serum samples of patients with cryptogenic and LAA stroke. In accordance with the mRNA expression in whole blood, the levels of several tested miRNAs were higher in serum samples collected during acute stroke compared to the 1-year follow-up in patients with cryptogenic stroke, with the most prominent expression of miR-21 (p < 0.0001), followed by miR-122 (p = 0.0001) and miR-155 (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2). The differences between the two time-points in patients with LAA stroke did not reach statistical significance. When cryptogenic and LAA samples were analysed as a single cohort, the increased serum level of miRNA-21 (p = 0.003) and miRNA-155 (p = 0.02) was detected in the LAA samples at the 1-year follow-up (Supplementary Figure S2).

Fig. 2.

Relative serum levels of selected inflammation-associated miRNAs. The relative expression of miRNAs was assessed from the total RNA purified from the serum of patients with cryptogenic (Cryp) (A) and LAA (B) stroke immediately after the stroke onset (Cryp 1, LAA 1) and 1 year later (Cryp 2, LAA 2). Paired two-tailed t-test, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

Gene expression and stroke severity

First, a linear regression analysis evaluating the association of stroke severity on admission with the expression of different genes was performed. In patients with cryptogenic stroke, the ICAM1 (p = 0.004), CASP1 (p = 0.01), PYCARD (p = 0.01), NFKBIA (p = 0.02), IL-6 (p = 0.05), miR-146a (p < 0.001), and miR-155 (p = 0.004) expression were significantly associated with stroke severity on admission. However, in the multiple linear regression analysis, none of the studied genes were significantly associated with stroke severity on admission, while lower expression levels of NLRP3 were associated with stroke severity at the 1-year follow-up (p < 0.001). In patients with LAA stroke, there were no significant associations between stroke severity and the expression of genes both at the mRNA and miRNA levels in either time-point (Supplementary material 1). As patients from both groups had favourable outcome (median NIHSS at 1 year 0 (p = 0.15), we could not assess whether the described differences in gene expression are associated with stroke outcome.

Gene expression and hs-CRP

The linear regression analysis showed no significant associations between hsCRP and the expression of studied genes in patients with cryptogenic stroke at the mRNA level. At the miRNA level, there was a significant association between hs-CRP and miR-21 expression level (p = 0.02) during acute stroke, which also persisted in the multiple linear regression model (p = 0.01). However, ICAM (p = 0.02), CASP1 (p = 0.01), NLRP3 (p = 0.02), and TNF (p = 0.0002) expression levels were significantly associated with the hs-CRP values at the 1-year follow-up in linear regression models, but the significance was lost in multiple regression model.

Despite the concentration of hs-CRP in serum being significantly higher at both time-points in patients with LAA stroke (Table 1), no significant relationship between hs-CRP and gene expression levels was detected at the mRNA and miRNA levels in either time-point (Supplementary material 1).

Associations between the modifiable/non-modifiable stroke risk factors and gene expression

First, we evaluated the associations between the modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors with each gene expression in the multiple logistic regression analysis in the acute phase of stroke. No significant associations were observed in patients with LAA. In contrast, when assessing the modifiable risk factors, we observed an association between dyslipidaemia and miR-21 expression (p = 0.02) in cryptogenic stroke and diabetes and NFKBIA expression (p = 0.05) in LAA stroke. Recent infection was significantly associated with PYCARD (p = 0.02), IL6 (p = 0.03), IL1β (p = 0.005), miR-146a (p = 0.003) and miR-155 (p = 0.004) expression in multiple regression analysis (Supplementary material 1).

In addition, the two-way repeated measures ANOVA analysis was used to evaluate whether the mean differences in gene expression at the 1-year follow-up compared to acute stroke were associated with cardiovascular risk factors and stroke severity. Most prominent differences were found in patients with cryptogenic stroke with no cardiovascular risk factors (Supplementary Table S2). A similar pattern of change in both stroke subtypes was observed for NFKBIA in non-diabetic patients and for TNFα in patients without hypertension or dyslipidaemia.

Discussion

We assessed the expression of selected genes related to inflammation at mRNA and miRNA levels for two etiologic subtypes of young patients with ischemic stroke, both in the acute and chronic phases of the disease. We found that the pattern of gene expression was different in acute cryptogenic and LAA stroke, with increased levels of mRNAs encoding inflammation-related genes (ICAM1, CXCL8, TNF, PYCARD, IL1B, IL18) and miRNAs (miR-21, miR-155 and miR-122) in cryptogenic stroke but not in LAA stroke. Only the expression of NFKBIA was increased in both stroke subtypes, although the effect was significantly stronger in cryptogenic stroke. As the gene expression levels at the 1-year follow-up did not significantly differ between the patients with cryptogenic and LAA stroke, these results may indicate that the inflammatory response in patients with LAA stroke is less evident than that of cryptogenic stroke in the acute phase. One possible explanation could be that atherosclerosis in patients with LAA stroke accompanies a low level of chronic inflammation33, which is not associated with studied genes. Still, this inflammatory background reduces the acute responses in patients with LAA stroke.

The activation of the inflammatory cascade in brain ischemia is a highly complex process in which inflammasomes often represent one of the earliest pathways. Although inflammasome activation has been extensively studied19–21, there are no reports on targeted analysis of inflammasome-related genes in patients with acute stroke. A previous study showed that the serum concentration of NLRP3 was increased during acute stroke and was related to the risk of malignant brain oedema34. Animal studies have been promising and already led to studies on inflammasome inhibitors as possible therapeutic agents in cerebral ischemia9,22. Among inflammasome-related genes, PYCARD, IL1B, and IL18 were upregulated at the mRNA level during the acute phase of cryptogenic stroke in our cohort, which may indicate inflammasome activation. However, further studies are needed to assess the presence of active IL-1β in younger patients in the acute phase of cryptogenic stroke.

It has been shown that the transcription of inflammasome-related genes and IL1B are regulated by the NF-κB pathway20–22. We assessed several genes from the NF-κB pathway. Only the NFKB1A gene expression was significantly upregulated during the acute phase of both stroke subtypes, with a more prominent change in cryptogenic stroke. However, ICAM1, CXCL8, and TNF were upregulated only in cryptogenic stroke. This indicates that in the acute phase of LAA stroke, the NF-κB pathway is activated to a lesser extent.

Stroke is a complex disease with different aetiologies. Our findings suggest that the inflammatory cascade activation pattern is different in cryptogenic and LAA stroke; therefore, it might play a role in targeting inflammation in stroke with possible therapeutics in the future. Former gene expression studies partially identified the aetiology of cryptogenic stroke using gene panels characterising either LAA or cardioembolic stroke13,14,18. It is important to note that in previous studies, the NF-κB signalling was found to be upregulated in cardioembolic stroke14. This could indicate that some of our patients with cryptogenic stroke could have had cardioembolic aetiology. However, this is a speculation. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine the “true” aetiology of cryptogenic stroke.

We also combined the gene expression results with the clinical data of our patients. It revealed that in patients with cryptogenic stroke, more prominent changes, mostly increased expression in the acute phase of stroke, were noted in patients with fewer cardiovascular risk factors and milder stroke. The changes between the time-points were less evident in patients with LAA stroke. These data may indicate that regarding stroke in patients with no cardiovascular risk factors, the inflammatory response to stroke is more pronounced and/or refers to different aetiology. In addition, a slightly increased expression of particular inflammation-related genes in acute cryptogenic stroke compared to later time-point and LAA stroke might indicate that these genes may serve as potential biomarkers for predicting outcome in cryptogenic stroke patients. However, as patients from both groups had equally favourable outcome after one year, we could not determine association between gene expression and outcome. Further studies utilizing whole transcriptome analysis to find additional affected genes, and using a larger validation cohort would help to test whether there is association of a set of pro-inflammatory genes, which expression could be used as biomarker to predict outcome and/or aetiology. Although a mild increase in the CRP level is considered a nonspecific marker of the acute phase of stroke, its association with stroke and atherosclerosis is evident33. We found no association of hsCRP with the inflammatory gene expression at the acute stage. However, ICAM1, TNF, CASP1, and NLRP3 showed significant association 1 year after cryptogenic stroke. At the gene expression level, the inflammatory response in our cohort was more evident in patients with cryptogenic stroke. Moreover, the serum hs-CRP concentration was significantly higher at both time-points in patients with LAA stroke. This finding may further indicate that the pattern of inflammatory responses is different in cryptogenic and LAA stroke both in the acute phase and at the 1-year follow-up.

In addition to mRNA expression, we evaluated the serum levels of miRNAs associated with the regulation of inflammatory responses and atherosclerosis. In line with the increase in mRNA levels of inflammation-associated protein-coding genes, there was a significant upregulation of miR-21, miR-122, and miR-155 and a tendency to upregulate miR-146a in the serum of patients with acute cryptogenic stroke but not in those with acute LAA stroke. When analysed in the context of clinical characteristics, a significant relationship was found between stroke severity and miR-21, miR-122, and miR-155 expression levels in serum using linear and multiple regression analyses for miR-21. The expression and function of the miRNAs in this study (and other miRNAs outside this study’s context) have been assessed previously in association with stroke25,32,35 and other diseases36. miR-21 has been shown to be upregulated during acute ischemic stroke and is known to decrease the level of inflammation32,35. In addition, miR-21 is atheroprotective. Its deficiency has been shown to lead to the activation of the NF-κB signalling in macrophages in mice37. miR-155 enhances inflammation through targeting the suppressor of cytokine signalling 136,37. Moreover, its inhibition led to altered inflammatory responses in a mouse model of experimental stroke38. miRNA-122 has also been shown to have a protective effect in a mouse model of ischemic stroke39. It should be also noted that among the genes measured in this study, PYCARD is predicted direct target gene for miR-122 and miR-155 according to TargetScan40 while the other studied genes can be influenced indirectly via regulation of the inflammatory pathways. Therefore, our study indicates that upregulation miR-21, miR-122, and miR-155 in the serum during acute stroke is not only sign of increased inflammation, but may also be associated with the regulation inflammatory responses in stroke. However, further studies are needed to clarify the importance of miRNA regulation in association with cryptogenic stroke.

The main limitations of our study are the relatively small sample size and unequal number of patients in the study groups. However, we assume that the homogeneity of the patient groups that include only young-onset stroke, profound clinical data, and detailed stroke aetiology classification compensated for this. Despite this, we cannot definitely exclude that less pronounced differences in LAA stroke may be partially due to a smaller sample size. Another limiting factor was that we assessed only a small number of genes. Moreover, we did not assess whether the inflammasome was indeed activated using the measurement of serum levels of IL-18 and IL-1β as the samples were collected over a long period, and these cytokines are relatively unstable. Further studies, including whole transcriptome analysis, comparisons with a healthy control group and analyses in a validation cohort would help to get more information regarding the mechanisms of cryptogenic stroke.

As stroke is an emergency, recruiting patients into clinical trials, especially in the acute phase of the disease, is often complicated. The strengths of our study are a homogeneous group of stroke patients, focus on a specific mechanism of pathogenesis, blood samples from both the acute and chronic phases of stroke, two levels of analysis including transcription and regulatory miRNAs, detailed clinical data, and stroke subtyping.

In conclusion, we have provided insights into young-onset stroke gene expression patterns in two aetiologic sub-groups. The inflammatory response was more prominent in cryptogenic stroke than in LAA stroke. Moreover, the increase in inflammatory cytokines was more evident in patients with no cardiovascular risk factors. Whether this is favourable for patients needs to be evaluated in further studies.

Defining stroke mechanisms and aetiologies in the future will probably involve clinical, imaging, protein, and genetic data combined into specific prediction models. Furthermore, many studies using detailed clinical data and biological samples are needed to develop such models.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Heti Pisarev for the assistance in statistical analysis and Editage for the English language editing.

Abbreviations

- LAA

Large-artery atherosclerosis

- Cryp

Cryptogenic

- NLRP3

Nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

- CASP1

Caspase 1

- PYCARD

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing caspase-recruitment domain

- ICAM1

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- TNFα

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha

- NFKB1A

Nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 1A

- EEF1A1

Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 1 Alpha 1

- ΔΔCt

Delta–delta cycle threshold

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- hs-CRP

High-sensitive C-reactive protein

- miRNA

Micro-ribonucleic acid

- CXCL8

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IL-18

Interleukin-18

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1 beta

- IQR

Interquartile range

Author contributions

R.V., Ana.R. and J.K. participated in the study design, protocol preparation and overall management of the study. R.V., K.J. and J.K. collected the clinical data and biological samples. K.J. and R.V. were responsible for the statistical analysis of the data (together with Heti Pisarev who is not listed as an author). Anu.R. was responsible for biological sample processing and all laboratory experiments. Ana.R. prepared all the figures used in the manuscript. R.V. wrote the main manuscript text and all authors have reviewed and accepted the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the grants PRG1915 and PRG1259 from the Estonian Research Council.

Data availability

The original raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74995-0.

References

- 1.Ekker, M. S. et al. Risk factors and causes of ischemic stroke in 1322 young adults. Stroke 54, 439–447 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yesilot Barlas, N. et al. Etiology of first-ever ischaemic stroke in European young adults: The 15 cities young stroke study. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 1431–1439 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putaala, J. et al. Analysis of 1008 consecutive patients aged 15 to 49 with first-ever ischemic stroke the Helsinki young stroke registry. Stroke 40, 1195–1203 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vibo, R. et al. Estonian young stroke registry: High burden of risk factors and high prevalence of cardiomebolic and large-artery stroke. Eur. Stroke J. 6, 262–267 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowalski, R. G. et al. Rapid activation of neuroinflammation in stroke: plasma and extracellular vesicles obtained on a mobile stroke unit. Stroke 54, e52–e57 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayaraj, R. L., Azimullah, S., Beiram, R., Jalal, F. Y. & Rosenberg, G. A. Neuroinflammation: Friend and foe for ischemic stroke. J. Neuroinflamm. 16, 1–24 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liesz, A. & Simats, A. Systemic inflammation after stroke implications for post-stroke comorbidities. EMBO Mol. Med. 14, e16269 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikh, N., Merkler, A. & Iadecola, C. Inflammation, autoimmunity, infection, and stroke: Epidemiology and lessons from therapeutic intervention. Stroke 51, 711–718 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han, P.-P., Han, Y., Shen, X.-Y., Gao, Z.-K. & Bi, X. NLRP3 inflammasome activation after ischemic stroke. Behav. Brain Res. 453, 114578 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montaner, J. et al. Multilevel omics for the discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets for stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16, 247–264 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh, K. P., Miaskowski, C., Dhruva, A. A., Flowers, E. & Kober, K. M. Mechanisms and measurement of changes in gene expression. Biol. Res. Nurs. 20, 369–382 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falcione, S., Kamtchum-Tatuene, J., Sykes, G. & Jickling, G. C. RNA expression studies in stroke: What can they tell us about stroke mechanism?. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 33, 24–29 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jickling, G. C. et al. Signatures of cardioembolic and large vessel ischemic stroke. Ann. Neurol. 68, 681–692 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Berrocoso, T. et al. Cardioembolic Ischemic stroke gene expression fingerprint in blood: A systematic review and verification analysis. Transl. Stroke Res. 11, 326–336 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jickling, G. C. et al. Profiles of lacunar and non-lacunar stroke. Ann. Neurol. 70, 477–485 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostulas, N., Pelidou, S. H., Kivisäkk, P., Kostulas, V. & Link, H. Increased IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-17 mRNA expression in blood mononuclear cells observed in a prospective ischemic stroke study. Stroke 30, 2174–2179 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanne, T. M. et al. Longitudinal study reveals long-term pro-inflammatory proteomic signature after ischemic stroke across subtypes. Stroke 53, 2847–2858 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jickling, G. C. et al. Prediction of cardioembolic, arterial, and lacunar causes of cryptogenic stroke by gene expression and infarct location. Stroke 43, 2036–2041 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, L. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A therapeutic target for cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15, 84770 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jover-Mengual, T. et al. The role of NF-κB triggered inflammation in cerebral ischemia. Front. Cell Neurosci 15, 633610 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fann, D. Y. W. et al. Evidence that NF-κB and MAPK signaling promotes NLRP inflammasome activation in neurons following ischemic stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 1082–1096 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alishahi, M. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome in ischemic stroke: As possible therapeutic target. Int. J. Stroke 14, 574–591 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng, J. et al. TRIM9-mediated resolution of neuroinflammation confers neuroprotection upon ischemic stroke in mice. Cell Rep. 27, 549–560 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartel, D. P. Metazoan microRNAs. Cell 173, 20–51 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jickling, G. C. et al. MicroRNA expression in peripheral blood cells following acute ischemic stroke and their predicted gene targets. PLoS One 9, e99283 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamtchum-Tatuene, J. & Jickling, G. C. Blood biomarkers for stroke diagnosis and management. NeuroMol. Med. 21, 344–368 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotb, H. G. et al. The expression of microRNA 146a in patients with ischemic stroke: An observational study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 12, 273–278 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaudet, A. D., Fonken, L. K., Watkins, L. R., Nelson, R. J. & Popovich, P. G. MicroRNAs: Roles in regulating neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist 24, 221–245 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández-Tussy, P., Ruz-Maldonado, I. & Fernández-Hernando, C. MicroRNAs and circular RNAs in lipoprotein metabolism. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 23, 33 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams, H.P., Bendixen, B.H., Kappelle, L.J., Biller, J., Love, B.B., Gordon, D.L. & Marsh, E.E. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Stroke 24, 35–41 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Untergasser, A. et al. Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1–12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai, P., Liao, Y., Lin, H., Lin, R. & Juo, S. Serum microRNA-21 and microRNA-221 as potential biomarkers for cerebrovascular disease. J. Vasc. Res. 50, 346–54 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kelly, P. J., Lemmens, R. & Tsivgoulis, G. Inflammation and stroke risk: A new target for prevention. Stroke 52, 2697–2706 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, Y. et al. Association between serum NLRP3 and malignant brain edema in patients with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. 21, 341 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou, J. & Zhang, J. Identification of miRNA-21 and miRNA-24 in plasma as potential early stage markers of acute cerebral infarction. Mol. Med. Rep. 10, 971–976 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebane, A. microRNA and allergy. In MicroRNA: Medical Evidence (Santulli, G.). 331–52 (Springer Cham, 2015).

- 37.Jiang, Q. et al. Pathogenic role of microRNAs in atherosclerotic ischemic stroke: Implications for diagnosis and therapy. Genes Dis. 9, 682–696 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pena-Philippides, J. C., Cabarello-Garrido, E., Lordkipanidze, T. & Roitbak, T. In vivo inhibition of miR-155 significantly alters post-stroke inflammatory response. J. Neuroinflamm. 13, 287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, M. et al. MicroRNA-122 protects against ischemic stroke by targeting Maf1. Exp. Ther. Med. 6, 616 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agarwal, V., Bell, G. W., Nam, J.-W. & Bartel, D. P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 4, e05005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.