Highlights

-

•

The study addresses a literature gap on the utilization, reuse and disposal of thermoplastic masks.

-

•

Thermoplastic masks are often reused in curative treatments, government-run and busy centres.

-

•

The preferred way of disposal of used thermoplastic masks is through biomedical waste management.

-

•

Radiotherapy technologists are conscious for environmental effects of thermoplastic mask disposal.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, Thermoplastic mask, Radiotherapy technologist, Immobilization device, Biomedical waste

Abstract

Purpose

Radiotherapy (RT) relies on devices like thermoplastic masks (TMs), that are made up of specialized thermoplastic polymers, and used as an immobilization tool. The study aims to assess the practice of usage and reuse of TMs among radiation therapy technologists (RTTs) in India and explore their awareness of environmental impact during disposal.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among RTTs working in different healthcare settings. A structured questionnaire designed by a team of RTTs and radiation oncologists was used to collect responses. Questionnaire encompassed data pertaining to demographics, existing patient load, daily utilisation and reuse practice of TMs, preferred method of disposal and awareness of RTTs regarding environmental consequences associated with TM disposal.

Results

A total of 430 RTTs participated in the study, with a median age of 31 years and a median professional experience of 8 years. Among the participants, 213 (49.6 %) reported daily TM utilization in more than 50 patients. TM reuse was reported by 350 (81.1 %) RTTs, with 257 (60 %) reusing TMs in both curative and palliative treatments. Reuse of TMs was observed more commonly in RTTs working in government facilities (81.2 %).

Regarding disposal preferences, 381 (88.6%) participants preferred discarding used TMs in biomedical waste and 64.8% of these ultimately ended up as discarded scrap. Awareness regarding adverse environmental impact associated with TM disposal was reported by 320 (74.4%) participant RTTs.

Conclusion

The study highlights the prevalent practice of reuse of TMs, especially in curative treatments, government-run facilities and busy treatment settings. Additionally, it emphasises the imperative for enhanced bio-medical waste management practices to facilitate more effective handling and disposal of used TMs.

Introduction

Modern radiotherapy (RT) endeavors to optimise the therapeutic ratio by delivering conformal doses to the target while minimising exposure to nearby organs and is significantly aided by optimal patient immobilization, especially in fractionated treatments [1], [2], [3]. Among the widely adopted and universally embraced immobilization tools are thermoplastic masks (TMs). [2], [3] TMs exhibit a remarkable characteristic whereby they can be rendered pliable and shaped when subjected to heat, subsequently returning to a firm state when exposed to lower temperatures. Leveraging this property, TMs are customized for individual patients by heating thermoplastic sheet to a specific temperature and once it reaches in a malleable state, the sheet is delicately conformed to the specific region of patient’s body. As it cools, the mask solidifies, maintaining the precise form essential for treatment. Despite their inherent rigidity, TMs are meticulously designed with the utmost consideration for patient comfort. [2], [4] There are multiple manufacturers of TMs in the market and customized TMs are typically made up of specialised thermoplastic polymers, such as polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, or poly caprolactone. Different substances may also be blended into the polymer to bring about desirable properties in the mask. [5].

In practice, TMs can be readily sanitised and reconfigured for use with different patients. [6] Nevertheless, if a TM experiences significant damage, becomes contaminated with bodily fluids or secretions, or undergoes excessive modifications for therapeutic reasons, it becomes unsuitable for reuse. [1] Most manufacturers recommend one-time use of these TMs with re-use being limited to cases where adjustments are required due to changes in patient’s body contour over the course of the extended RT treatments. [1], [6].

While TMs are commonly reused in daily practices, there is a scarcity of literature addressing their practical application. [6] Another unexplored aspect of TM utilization pertains to their proper recycling and final disposal, in compliance with infection control guidelines and environmental responsibility standards [7]. Manufacturers usually recommend discarding the TMs as household waste citing its biodegradability. While there are numerous studies on the extended degradation profiles of petroleum-based polymers which are base materials used in TMs, research on the degradation of TMs as final products is insufficient. Therefore, the primary aim of this survey is to evaluate the reuse of TMs among radiation therapy technologist (RTT)/ radiographer/ radiation technician, as well as to gauge their awareness of the environmental impact associated with the disposal of used TMs. Additionally, the secondary purpose of the study is to provide an information that can be incorporated in formulating guidelines and policies to better balance the use and reuse of TMs in healthcare with the need to protect the environment.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Approval from the Institutional Ethics committee was obtained prior to commencing this cross-sectional survey, which was conducted among RTTs working in diverse settings across India. Participant enrollment occurred from February 1, 2023, to May 31, 2023.

Development of structured questionnaire

A team of RTTs and Radiation oncologists collaboratively developed a structured questionnaire, drawing upon their experience and the common challenges encountered in the daily reuse and disposal of used TMs.

The initial segment of the questionnaire encompassed fundamental demographic and professional inquiries, covering participant details like age, years of professional experience, workplace, and the treatment units available at their respective centres. The subsequent section of the questionnaire aimed to gather data on the routine utilization of TMs in RT treatments. This section included questions regarding the number of patients treated with TM and their preferred thickness for the material.

The next was a series of questions designed to gather information about the reuse of TMs. These questions aimed to understand the patterns of TM reuse, including whether these masks were routinely reused in their respective centres and, if so, for what purpose they were reused. If TM reuse occurred in curative settings, additional questions were posed about the specific techniques for which they were routinely reused. In the case of TM reuse in palliative settings, questions focused on the preferred type of TM for reuse. Additionally, we inquired about the frequency with which RTTs felt comfortable reusing the masks. The final section of the questionnaire covered topics such as the preferred methods of discarding TMs and RTT’s awareness of the environmental impact of TM disposal (Supplemental data S1).

Procedures of data collection

Members of the Association of Radiation Therapy Technologists of India (ARTTI), an official organization representing RTTs in India, were contacted through their registered email addresses. They were then provided with a survey questionnaire through Google forms and were invited to participate voluntarily. To ensure anonymity, we did not seek any direct information revealing the participant’s identity. A four-month window was provided for questionnaire completion after which response collection was concluded.

Data analysis

Responses were gathered and the data was imported from completed Google forms. The statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS (version 29.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), employing descriptive statistics like frequency, percentage, mean, median, and standard deviation to summarize the findings. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to see the statistical association between variables and p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Participant profile summary

Data was gathered from 430 RTTs who successfully completed the questionnaire. The median age of participants was 31 years (range: 24 to 60 years). The median professional experience among the RTTs was eight years (range: 1to 37 years) and one-third of the RTTs were having more than a decade of professional service experience. More than half of the RTTs were employed in private healthcare settings, while two-thirds exclusively utilized linear accelerators (LAs) in their centers. Among survey respondents, 54 % (213/394) of the younger RTTs (<40 years old) were employed in private settings, 31 % (123/394) in government institutions, and the remaining 15 % (58/394) in trust hospitals. A comprehensive breakdown of the demographic and professional characteristic of the participating RTTs can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and professional characteristics of participating RTTs.

| Parameter | Subgroup | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ≤30 years | 211 (49.0 %) |

| 31–40 years | 183 (42.5 %) | |

| 41–50 years | 23 (5.4 %) | |

| >50 years | 13 (3 %) | |

| Professional experience | <3 years | 86 (20 %) |

| 3 to 5 years | 81 (18.8 %) | |

| >5, ≤10 years | 131 (30.4 %) | |

| >10 years | 132 (30.7 %) | |

| Working setup | Private | 226 (52.6 %) |

| Government | 143 (33.2 %) | |

| Trust | 61 (14.2 %) | |

| Available treatment unit in working setup | Linear accelerator only | 283 (65.8 %) |

| Both linear accelerator and cobalt setup | 138 (32.1 %) | |

| Cobalt only | 9 (2.1 %) | |

| Daily utilization of thermoplastic mask at respective setups | <30 | 89 (20.7 %) |

| 30–50 | 128 (29.8 %) | |

| 51–100 | 127 (29.5 %) | |

| >100 | 86 (20 %) | |

| Preferred thickness of thermoplastic masks being utilized in respective setups | ≤2 mm | 198 (46 %) |

| >2 mm | 120 (27.9 %) | |

| Both ≤2 mm and >2 mm | 112 (26.1 %) |

RTT: Radiotherapy technologist.

Usage and reuse patterns of thermoplastic masks by RTTs

Nearly half of the RTTs reported using TMs on over 50 patients per day, with a preference for TMs that were of 2 mm thick or less (Table 1). Majority of RTTs (n = 350/430, 81.1 %) reported reusing of TMs, with nearly three-quarters expressing confidence in the practice not only for palliative but also for curative treatment protocols (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patterns of reuse of thermoplastic masks by radiotherapy technologists (n = 430).

The practice of reusing TMs was not associated with age of RTTs [≤ 30 years (171/211, 81.0 %), 31–40 years (147/183, 80.3 %), age 41–50 years (20/23, 87.0 %) and > 50 years of age (12/13, 92.3 %) (p = 0.65) (Supplement material S2). Also, reuse of TMs was observed more often among RTTs working in government-runfacilities (n = 128/143, 89.5 %) and trust hospitals (n = 52/61, 85.2 %) compared to those in private settings (n = 170/226, 75.2 %) (p = 0.00) (Supplement material S3). Moreover, RTTs in government-run facilities reported higher rates of TM reuse in curative settings (n = 104/128, 81.2 %) compared to RTTs in trust hospitals (n = 36/52, 69.2 %) and private settings (n = 117/170, 68.8 %) (p = 0.00) (Supplement material S3). Additionally, centers with a daily TM utilization rate exceeding 100 (n = 79/86, 91.9 %) and between 50–100 (n = 108/127, 85 %) had higher rates of TM re-use compared to those with daily utilization rates of either 30–50 (n = 97/128, 75.8 %) or less than 30 (n = 66/89, 74.1 %) (p = 0.00) (Supplement material S4).

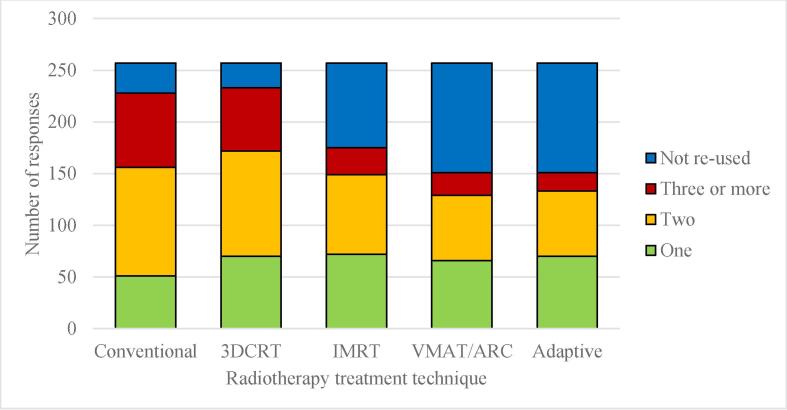

Nearly three fourth (n = 257/350, 73.4 %) of the responded RTTs expressed a high level comfort with reusing TMs for curative treatments. The breakdown of their responses, based on different curative RT techniques and the frequency of TM reuse, is presented in Fig. 2. For curative treatments, a majority of the RTTs indicated reusing TMs at least twice. Notably, multiple reuses (at least twice or more) of TMs were more prevalent in conventional RT technique (n = 177/228, 77.6 %) and 3-dimensional conformal RT (3DCRT) (n = 163/233, 69.9 %) compared to intensity modulated RT (IMRT) (n = 103/175, 58.8 %), image-guided RT (IGRT) (n = 85/151, 56.3 %), and adaptive RT (81/151, 53.6 %).

Fig. 2.

Patterns of reuse of thermoplastic masks in curative setting as per technique (n = 257).

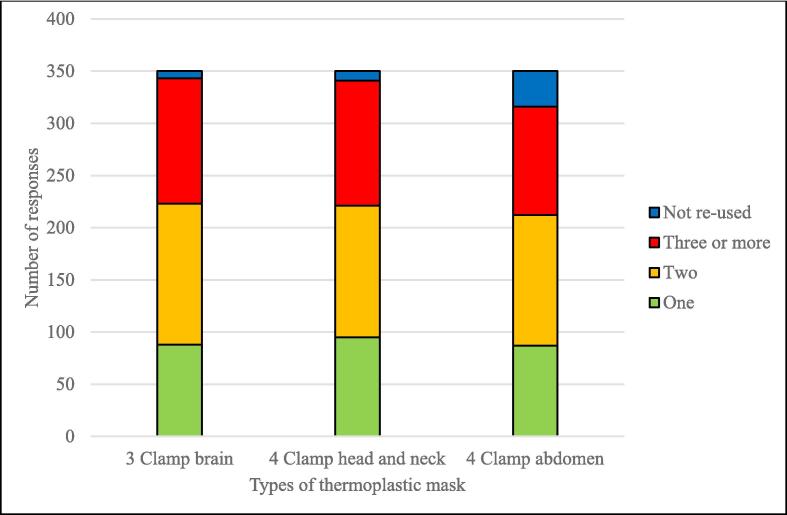

Furthermore, in palliative settings, 350 (81.4 %) RTTs expressed re-use of TMs. More than two thirds of them were re-using TMs for at least two treatment courses. The reuse patterns of TMs in palliative settings is illustrated in Fig. 3. RTTs exhibited higher level of reuse of 3-clamp brain TMs (n = 343, 98 %) and 4-clamp head and neck TMs (n = 341, 97.4 %) as compared to 4-clamp abdominal and pelvic TMs (n = 316, 90.3 %).

Fig. 3.

Patterns of reuse of thermoplastic masks in palliative setting as per mask type (n = 350).

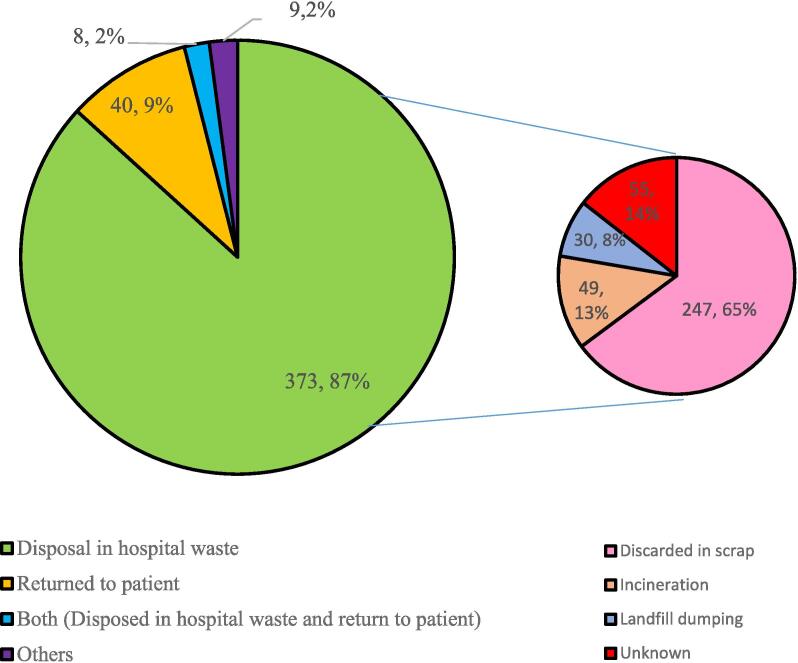

Methods of discarding used thermoplastic masks

The majority of RTTs surveyed (n = 381/430, 88.6 %) reported that they routinely prefer discarding TMs in hospital biomedical waste (BMW). In contrast, 48 RTTS (11.1 %) indicated that they return TMs to patient or their caregiver after treatment (Fig. 4). The preferred method of discarding TMs in BMW was more common among RTTs working in private healthcare settings (n = 220/226, 97.3 %) and trust hospitals (n = 56/61, 91.8 %) compared to those employed in government-run institutions (n = 105/143, 73.4 %) (p = 0.00) (Supplement material S3). Conversely, the return of TMs to patients upon conclusion of the treatment was more frequently observed in government-run healthcare settings (n = 37/143, 25.9 %) as compared to trust hospitals (n = 8/61, 13.1 %) and private settings (n = 3/226, 1.3 %) (p = 0.00) (Supplement material S3). Among participant RTTs who indicated that they routinely dispose of TMs in hospital waste, it was found that the majority (n = 247/381, 64.8 %) reported that these masks were being discarded in scrap and only 49/381 (12.9 %) RTTs mentioned incineration as their disposal method (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Reported predominant patterns of disposal of used thermoplastic masks by RTTs (n = 430) Small pie chart describes reported final disposal of discarded thermoplastic masks in hospital waste.

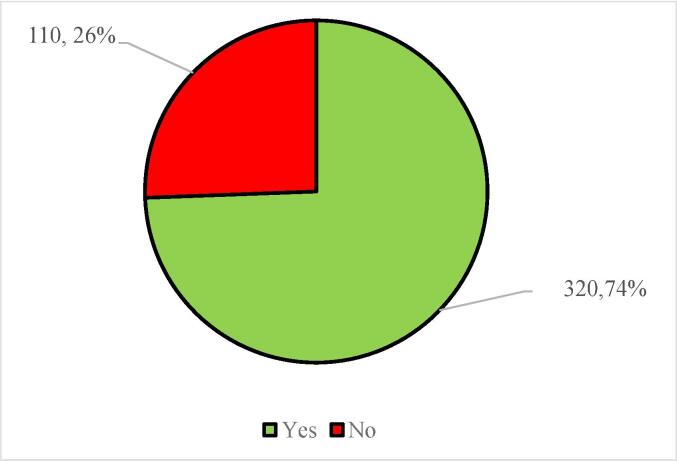

A significant number of RTTs (n = 320, 74.4 %) expressed awareness of the adverse environmental impacts with their TMs disposal (Fig. 5). Notably, there were no discernible differences observed in awareness regarding environmental impact of TMs disposal based on either the working setup (p = 0.63) or age (p = 0.72) (Supplement material S2, S3).

Fig. 5.

Awareness of RTTs about adverse impact of discarded thermoplastic masks on environment (n = 430).

Discussion

The advantage of material used in TMs makes them the preferred option of immobilization devices, offering an additional benefit of potential reuse. Numerous studies had highlighted the significance of TM usage and customisation, elucidating their impact on treatment parameters, toxicity profiles, enhanced compliance and ultimately, disease outcomes [2], [3]. However, this study marks the inaugural attempt to investigate the patterns of TM usage, re-use, and the subsequent disposal process practiced by RTTs.

The profile of participants in the survey

RTTs play a pivotal role in the comprehensive management of TMs [8], spanning from simulation to treatment and disposal. Their perspectives on TM usage and reusability are of paramount importance. Consequently, this survey was conducted among RTTs working in diverse healthcare settings across the nation. The response rate, albeit modest, yielding 430 responses from a total of contacted 1,200 registered members of ARTTI, representing 35.8 % participation. Notably, a significant proportion of the participating RTTs belonged to the younger age group in early stages of their careers. Additionally, the majority were employed in private facilities, with LAs as the preferred treatment modality. [9].

Usage and reuse of thermoplastic masks

Historically, a wide array of materials, including metals, glass, ceramics, and more, have been explored for use in medical devices [10] However, plastic polymers have emerged as the preferred choice due to their advantageous properties, such as biocompatibility, lightweight, cost-effectiveness, and greater acceptance among users. [10] Within the realm of plastic polymers used in medical industry, thermoplastics, which can undergo multiple cycles of heating and cooling, resulting in alterations between soft and hard states, are used extensively in cancer care, particularly in radiation oncology. [11] As already mentioned, these materials are routinely incorporated as the preferred immobilization devices by RTTs as a part of their daily treatment protocols, a trend highlighted in the survey. Additionally, a majority of participating RTTs were well-versed in the applications of TMs, with over three-fourths of the surveyed centers conducting more than 30 treatments utilising TM-immobilization devices each day. Furthermore, the preference for the thinner TMs suggests that their efficacy in immobilization may remain uncompromised.

The International atomic energy agency (IAEA) previously recommended the reuse of TMs up to five times. [12]) However, the recent guidelines gave significant consideration to increased use of advanced high precision techniques and advised against the use of inconsistent immobilization devices, as they can result in inaccuracies during setup and treatment delivery [1] Furthermore, the IAEA recommends limiting the reuse of TMs to its “useful lifespan’. [1] Extensive reuse of TMs is not endorsed due to potential loss of rigidity, which can result in inadequate immobilization and lower treatment quality. [6] However, in the present survey, 80 % of RTTs reported regular reuse of TMs, predominantly in curative rather than only palliative treatments. In curative settings, over 65 % of conventional and 3DCRT plans involved multiple reuses of TMs, whereas this practice was less prevalent in IMRT and VMAT cases, with reuse rates ranging from 50 % to 60 %. This difference is likely due to departmental policies that intentionally limit TM reuse in high-precision treatments, like IMRT and VMAT, where even minor setup deviations could result in significant underdosing or overdosing of the target area. Another contributing factor might be the socioeconomical status of patients; those with limited financial resources may opt for conventional or 3DCRT plans, where TM reuse is more common. Notably, the only study that reported on TM reuse in head and neck cancer patients treated with VMAT reported setup errors of less than 3 mm, suggesting that with careful management, reuse might still be feasible in high-precision treatments under specific conditions [16]. The factors used for deciding the ‘useful lifespan’ of TMs has not been evaluated and can be an avenue for further research.

The reuse of TMs was more common in healthcare settings that experienced high clinical activity and were either government-run-operated or run by trusts. This phenomenon can likely be ascribed to the pressing need for constant access to TMs and the financial limitations faced by patients seeking treatment in these institutions [13]. The substantial strain associated with cancer-directed treatment [14], limited coverage of government-run healthcare initiatives and insurance plans [15], and pronounced regional disparities in cancer prevalence versus the availability of RT facilities [9] might have collectively influenced a preference for already overburdened facilities, potentially resulting in suboptimal adherence to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Potential challenges associated with reuse of thermoplastic masks

Most vendors' guidelines stipulate that TMs are intended for one-time use. Over the time, thermoplastic materials tend to degrade due to repeated exposure to high temperatures, ultraviolet light, radiation, mechanical stress, and chemical oxidation in humid environments [16], [17], [18]. This degradation can result in polymer chain break, embrittlement, discoloration, surface cracking, and a reduction in mechanical and elastic properties [16], [17], [18]. As a result, the mask may lose its ability to conform accurately to the patient’s anatomy, leading to suboptimal immobilization and potentially compromising the precision of radiation delivery- particularly critical in curative treatments that require high-precision techniques, Alongside, there are also concerns regarding the cleaning of used TMs, as they may become contaminated with bodily fluids, making sterilization challenging with repeated use. Also, the remolding of used TMs often fail to produce compliant and technically sound masks. [1] The major clinical limitation of remolding is the formation of folds in the thermoplastic material during the customization process, which can result in higher surface doses and increased skin reactions. [6] Despite the potential cost-effectiveness of reusing TMs, many patients may not fully accept this practice, leading to discomfort and reduced compliance with the full course of RT. Furthermore, while some work discusses the reuse of TMs, notable among which is a single institute retrospective study which did not find any significant difference in shifts between first time use and once reused TMs for IMRT head and neck patients [19]. However, it should be further noted that the study was specific to a particular manufacturer and other existing literature mainly discusses the retention of elasticity in TM materials, after some reuse, with variations depending on the manufacturer [6]. Consequently, there is a significant gap in the literature regarding treatment outcomes with reused TMs. Hence, we raise a caution against indiscriminate use of such procedures as reusing TMs may jeopardize patient safety and radiation treatment efficacy. Any decisions concerning the reuse of TMs should be made after ensuring no change in efficacy of treatment in the specific setting or conditions.

Disposal of used thermoplastic masks

As plastic polymers, including thermoplastics, revolutionized the medical device industry, they also brought about concerns regarding their proper disposal after use. [10] Traditionally, the substantial quantities of plastic waste generated in healthcare facilities worldwide have been either sent to landfills or incinerated. [10], [20] Unfortunately, a significant portion of these disposed plastics ends up in marine ecosystems when sent to landfills, while incineration can release toxic byproducts, both of which can contribute to environmental contamination. [10] Studies show differential decomposition characteristics of petroleum-based polymers which make up the base material for most of the TMs. [21] Depending on the materials incorporated in it, the methods by which it has been treated and the environment for disposal, it can take anywhere from a few months to a couple of years for TM base material to degrade. That means conditions of decomposition leads to significant differences in degradation characteristics of biodegradable polymers. Hence, disposing them off in landfills where there are no established methods of degradation is a major concern, particularly in high volume centres where TMs can be a considerable amount of waste to process. Until specific guidelines or recommendations are provided for the disposal of used thermoplastic masks (TMs), standard methods commonly employed for disposing of other medical petroleum-based polymers or thermoplastic materials can be adapted for the disposal of used TMs.

This issue is further emphasized in the present survey, where it has been observed that the most common method of disposing of these TMs is through hospital BMW, with the majority ultimately ending up in landfills as discarded products. This trend appears to be more prevalent in busy government-run hospitals compared to private facilities. The main challenge faced by government-run sector institutes in India is restricted availability of funds for managing all types of biomedical waste, including thermoplastics. [13], [22] Again, the pressing need for expanding common biomedical waste treatment and disposal facilities (CBMWTF) has already been raised as a crucial step towards promoting responsible biomedical waste management (BMWM). [22].

Suggested recommendations for judicious use and disposal of thermoplastic masks

The noteworthy discoveries from the foundation of responsible BMWM encompasses 3Rs: reduce, reuse, and recycle. [22] This approach can also be applied to the prudent utilization of TMs. It is imperative to minimize the improper use of TMs. Moreover, there is inescapable need to explore more environmentally-friendly methods of immobilization. The primary challenge in this context pertains to achieving both rigidity and ensuring acceptable standards. The second facet, reuse is already being widely adopted in routine practice. However, this necessitates a thorough investigation into the technical challenges associated with reshaping and customizing used TMs in relation to their impact on RT treatment characteristics and outcomes. The third essential step is the recycling of TMs. Numerous techniques applied for recycling of used plastic polymers can be readily adapted for TMs. [7], [10], [19], [20] The low-temperature thermoplastic materials used in TMs can potentially be collected, remelted, and reprocessed into new products [23], [24], [25]. The environmental advantages of recycling extend beyond waste reduction by lowering the demand for energy-intensive virgin polymer production, which relies on fossil fuel extraction [23], [24], [25]. Therefore, implementing closed-loop systems where used TMs are collected, decontaminated, and recycled for both medical and non-medical applications could significantly improve the sustainability of radiotherapy services. These three core objectives can be realized through robust collaboration among TM manufacturers, suppliers, the radiation oncology community (including RTTs), hospital BMWM teams, and government-run regulatory bodies who can serve as the superior most authority.

Sustainability in radiotherapy is increasingly important as healthcare facilities aim to reduce their environmental impact. Implementing a recycling program for TMs can involve partnering with specialized recycling companies and establishing collection and segregation systems within treatment centers. Educating staff on recycling and proper disposal methods further enhances these efforts. Promoting the safe reuse of TMs through clear protocols and limiting reuse cycles based on the objective criteria can also help reduce waste.

Additionally, investing in sustainable alternatives such as biodegradable materials, optimizing mask production to minimize material waste, and encouraging green innovations are key strategies. Policymakers can support these initiatives by setting recycling mandates, implementing green procurement policies, and launching awareness campaigns. By adopting these measures, facilities can significantly reduce the environmental impact of TMs and promote a more sustainable approach to healthcare. Meanwhile, if TMs are routinely reused within the department, additional measures should be implemented, including appropriate storage solutions and thorough sterilization of TMs before remolding. The departmental budget may also need to adjust accordingly to reduce the necessity of TM reuse.

Strengths of the present study

The study gathered data surveying a significant number of RTTs working in diverse healthcare settings across India, enhancing applicability of the findings in this part. As the structured questionnaire was developed collaboratively by a team of RTTs and radiation oncologists, drawing from their expertise and experiences, which further strengthen its relevance in real world. The study stressed RTT’s awareness of the environmental impact of TM disposal, shedding light on an important and previously unexplored aspect of TM utilization. Again, the noteworthy findings from the survey is the increased environmental consciousness among RTTs regarding the improper disposal of TMs, and therefore, their enthusiasm for reusing TMs deserves appreciation.

Limitations of the study

Apart from usual limitations associated with a cross-sectional survey, the major limitation of the study includes generalisability of the findings to the other regions of the world with relatively different healthcare systems and practices. Alongside, the study relies on self-reported data from RTTs, which may be subject to recall bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of responses. Despite making every effort to include all pertinent questions, some were found to be missing, such as the method of cleaning and disinfecting used TMs when they undergo remolding, assessments of their physical and clinical acceptability, and potential environmentally friendly alternatives to TMs. The survey also did not answer the objective criteria used by RTTs to evaluate whether the TM was fit for reuse or not. Also, the study did not include a follow-up component to assess the long-term effects of TM reuse on treatment outcomes or actual environmental impact of TM disposal. Hence, it is highly desirable to conduct a follow up study with inclusion of actual hospital BMWM team.

Conclusion

The findings of the study highlights on reliance on thermoplastic masks as a preferred immobilization device in radiotherapy and the survey emphasizes a prevalent practice of its reuse, particularly in curative treatment protocols. There is a need for improved waste management practices, as most thermoplastic masks end up in landfills. The environmental awareness among RTTs regarding disposal of thermoplastic masks is encouraging and calls for a collective effort to address this issue responsibly.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

ARTTI: Association of Radiotherapy Technologists of India.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tipsro.2024.100278.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.van der Merwe D., Van Dyk J., Healy B., et al. Accuracy requirements and uncertainties in radiotherapy: a report of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2017;56(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1246801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhey L.J. Immobilizing and positioning patients for radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1995;5(2):100–114. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(95)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leech M., Coffey M., Mast M., et al. ESTRO ACROP guidelines for positioning, immobilisation and position verification of head and neck patients for radiation therapists. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2017;1:1–7. doi: 10.1016/J.TIPSRO.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhar D., Vadgaonkar R., Miriyala R., Kalita H., Parab P., Mahantshetty U. “Superhero” concept to avoid anesthesia for daily radiation treatment in childhood cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2023;19(3):813–815. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.jcrt_552_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuss M., Salter B.J., Cheek D., Sadeghi A., Hevezi J.M., Herman T.S. Repositioning accuracy of a commercially available thermoplastic mask system. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71(3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/J.RADONC.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoram F., Dharsee N., Mkoka D.A., Maunda K., Kisukari J.D. Radiation therapists’ perceptions of thermoplastic mask use for head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy at Ocean Road Cancer Institute in Tanzania: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18(2) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0282160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizan C., Mortimer F., Stancliffe R., Bhutta M.F. Plastics in healthcare: time for a re-evaluation. J R Soc Med. 2020;113(2):49–53. doi: 10.1177/0141076819890554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffey M., Naseer A., Leech M. Exploring radiation therapist education and training. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2022;24:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tipsro.2022.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munshi A., Ganesh T., Mohanti B. Radiotherapy in India: History, current scenario and proposed solutions. Indian J Cancer. 2019;56(4):359–363. doi: 10.4103/IJC.IJC_82_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph B., James J., Kalarikkal N., Thomas S. Recycling of medical plastics. Adv Industr Eng Polym Res. 2021;4(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/J.AIEPR.2021.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sastri VR. Material Requirements for Plastics Used in Medical Devices. In: Plastics in Medical Devices. Elsevier; 2014:33-54. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-3201-2.00004-5.

- 12.International Atomic Energy Agency. Practical Radiation Technical Manual: Mouldroom Techniques for Teletherapy.; 1999.

- 13.Kasthuri A. Challenges to Healthcare in India - The Five A’s. Indian J Community Med. 2018;43(3):141. doi: 10.4103/IJCM.IJCM_194_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dt A., Nair P., Abhijath V., Jha V., Aarthy K. Economics of cancer care: A community-based cross-sectional study in Kerala, India. South Asian J Cancer. 2020;09(01):07–12. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_382_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health insurance penetration still low - The Hindu BusinessLine. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/money-and-banking/health-insurance-penetration-still-low/article66699731.ece.

- 16.Thermoplastics - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/thermoplastics.

- 17.Herrera M., Matuschek G., Kettrup A. Thermal degradation of thermoplastic polyurethane elastomers (TPU) based on MDI. Polym Degrad Stab. 2002;78(2):323–331. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00181-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Blasi C. Transition between regimes in the degradation of thermoplastic polymers. Polym Degrad Stab. 1999;64(3):359–367. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(98)00134-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chumsuwan N, Lalita Romkedpikun BSc, Janyaporn Thongthae BSc, Tanapan Yousuk BSc. Comparative study of setup errors between new and reused thermoplastic masks in irradiated head and neck cancer patients. ASEAN J Radiol. 2023;24(2):122-136. doi: 10.46475/asean-jr.v24i2.808.

- 20.Okan M., Aydin H.M., Barsbay M. Current approaches to waste polymer utilization and minimization: a review. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2019;94(1):8–21. doi: 10.1002/JCTB.5778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das N., Chandran P. Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants: An Overview. Biotechnol Res Int. 2011;2011:1–13. doi: 10.4061/2011/941810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datta P., Mohi G., Chander J. Biomedical waste management in India: Critical appraisal. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10(01):006–014. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_89_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welle F. Twenty years of PET bottle to bottle recycling—An overview. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2011;55(11):865–875. doi: 10.1016/J.RESCONREC.2011.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aumnate C, Rudolph N, Sarmadi M. Recycling of Polypropylene/Polyethylene Blends: Effect of Chain Structure on the Crystallization Behaviors. Polymers 2019, Vol 11, Page 1456. 2019;11(9):1456. doi: 10.3390/POLYM11091456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Grigore M.E. Methods of recycling, properties and applications of recycled thermoplastic polymers. Recycling. 2017;2(4) doi: 10.3390/RECYCLING2040024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.