Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of shared decision-making informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology, for older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and determine its impact on patients’ glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and fasting plasma glucose), physical indicators (blood pressure and body mass index), self-management behavior, and self-efficacy.

Design

A double-arm-randomized controlled trial using a parallel group design was conducted.

Participants

124 older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus recruited from the endocrinology department or diabetes clinics were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 64) or control group (n = 60).

Interventions

Patients in the intervention group received shared decision-making informed dietary intervention through the digital health system and those in the controlled group received routine dietary management.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was HbA1c, and the secondary outcomes were fasting plasma glucose, blood pressure, body mass index, self-management ability, and self-efficacy.

Results

After 3 months of intervention, compared to the control group, the intervention group showed a statistically significant decrease in HbA1c, diastolic blood pressure, and fasting plasma glucose (P < 0.05). After the intervention, there were time, group main effects, and interaction effects on diabetes self-management ability and diabetes self-efficacy scores of older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

The intervention program based on a digital health system significantly improved glycemic control and enhanced self-care ability in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Practice implications

Clinicians can integrate digital health technology in behavior change intervention, especially in older adults with chronic disease.

Trial registration

It was registered and approved by the China Clinical Trials Center (ChiCTR2300071455).

Keywords: Shared decision-making, digital health, type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic diet, gerontological nursing, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a kind of chronic disease that affects 500 million people worldwide. 1 According to statistical estimates, 693 million adults will be diagnosed with diabetes by 2045. 2 T2DM is also a common chronic disease in older adults, and the health problems caused by it increase distress and reduce the quality of life of patients. 3 With the increasing trend of population aging, the rate of T2DM is increasing and presents new public health and societal challenges. 4 Research shows that the prevalence of T2DM is correlated with lifestyle choices. However, most patients with T2DM, do not maintain a healthy lifestyle and have unhealthy habits, such as prolonged sitting, imbalanced diet, and irregular sleep patterns. 4 For diet, as a part of lifestyle, the so-called appropriate meal choice might be difficult to source, because many patients with T2DM cannot obtain dietary information.4,5 However, as a noninvasive and low-cost treatment, dietary management plays a long-term and effective role in the management of diabetes. Especially after the initial clinical diagnosis, dietary management can reduce or delay diabetes-related complications to improve the quality of life of patients. 6

Recently, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has realized that the current management strategy has been unable to achieve the personalized management goals of patients with T2DM, especially older adults. 7 Older adults with T2DM face tougher challenges. In the process of self-management of diabetes, older adults with T2DM often encounter unique personal challenges due to cognitive dysfunction, poor self-care ability, and other problems.8,9 This leads to a lack of ability to obtain and recognize correct information in daily dietary decisions, making it difficult for older adults to make correct dietary decisions. 10 Therefore, when deciding on the dietary management of diabetes, it is necessary to consider the frequently occurring diseases and social and personal backgrounds of older adults, as well as their values, preferences, and goals.4,11,12

In the face of challenges in disease management, to better achieve patient-centered communication skills and good care for patients, shared decision-making (SDM) has been advocated for more than 40 years. 13 SDM is described as an interpersonal and interdependent process in which the health care provider and the patient jointly make specific decisions about health care. SDM combines cognitive, emotional, and relationship work to achieve communication, collaboration, and deliberation. 14 The SDM mode enables patients to have a clearer understanding of the changes in health outcomes and align their choices with their expectations and values. 14 Patient engagement implies recognizing and understanding the importance of playing an active role in one's health and having the knowledge, skills, and confidence for this purpose. 15 The theory of health management practice suggests that individuals learn and acquire knowledge and skills to enhance their health beliefs and attitudes, thereby contributing to the occurrence and maintenance of self-management behaviors. 16 The implementation of SDM in diabetes self-management can provide patients with knowledge and skills related to diabetes diet management through health communication, address the lack of health-related knowledge present for older adults, and provide a way to solve professional challenges in diet management for them. The doctor–patient collaboration in SDM allows older adults to participate in medical decision-making, to solve the dilemma of older adults being unable to make correct dietary decisions due to limited cognitive abilities. 17

However, because of concerns about cognitive deficits and multiple comorbidities, adults older than 60 years are often excluded from research trials. 18 In previous studies, the implementation of SDM through outpatient follow-up or inpatient treatment has increased the time for patients to seek medical care and often cost a lot of medical resources, which may lead to the fact that the research on SDM in patients with T2DM is rarely applied to older adults. The effectiveness of SDM in disease management in older adults has rarely been proven. With the development of information technology, digital information technology has been widely used as an auxiliary tool in clinical decision-making. 19 Based on the popularity of smartphones among older adults, 20 considering the characteristics of poor health information acquisition and recognition ability of older adults, as well as the theoretical framework of SDM, this study envisages using the existing digital health management system of the hospital as an auxiliary tool to standardize the process of SDM, improve the efficiency of information sharing in SDM, and apply it to the diet intervention of older adults with T2DM. The digital health system is an interactive Internet decision-making aid tool, in which, medical staff and patients who are both users of the tools can interact and exchange information. This digital health system collects, integrates, and presents a variety of data in a dashboard for older adults and healthcare professionals, supports older adults in diet management in daily life, and creates insights into potential barriers, behaviors, and outcomes. This information from digital health systems may help older adults and healthcare professionals to collaborate and engage in SDM.

The purpose of this study was to use digital health technology to provide SDM-informed dietary intervention for older adults with T2DM and to explore its effects on glycemic control and self-care ability.

Methods

Study design

A double-arm-randomized controlled trial using a parallel group design was conducted. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee. This article follows the requirements of the CONSORT statement. 21

Participants

The participants were older adults with T2DM from the endocrinology department or diabetes clinics at a tertiary hospital in southeastern China recruited from 16 May to 30 July 2023. Inclusion criteria: Patients with a clinical diagnosis of type 2 diabetes for more than six months according to the WHO criteria; hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level ≥ 7% in the 3 months before recruitment; age ≥ 60 years; access to a smartphone, and voluntary participation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: comorbid malignancy; physical limitations in diabetes self-care; hearing or visual impairment; limited physical activity due to other medical conditions; significant cognitive impairment; no internet facility; and recent participation in other research projects. Experienced clinical nurses carefully assessed the patients and referred those according to the criteria of researchers. Then, the trained researchers presented the participants with detailed information about this study, and if the participants agreed to participate, an informed consent form was signed.

Sample size

The sample size required to determine the effect of dietary interventions using SDM was calculated using pilot studies undertaken in previous literature.22–24 Based on an alpha risk of 5% and a beta risk of 10%, 100 subjects were included (50 per group). Considering a 20% dropout rate, we decided to include 130 patients to prevent attrition bias.

Randomization and blinding

Use computer-generated random sequences to evenly allocate participants between the two groups. A simple random plan was independently developed by a research assistant who was not involved in determining eligibility, providing dietary guidance, or evaluating results. Randomized numbers 0–4 were assigned to the control group, while numbers 5–9 were assigned to the intervention group. A study coordinator placed allocation details in non-transparent sealed envelopes and concealed them from recruiters and data collectors. The group allocation was not revealed until the patient's details were recorded by a clerical assistant. Recruitment, data collection, and data analysis were conducted by research assistants, researchers, and statisticians, respectively. Although it was not possible to blind researchers responsible for evaluating the outcomes due to the nature of the intervention, participants to their group assignments remained blinded to enhance the study's objectivity.

Intervention

Compared with the standard dietary management, all patients included in the intervention group received SDM-informed dietary intervention through the digital health system (see Supplemental Data). The dietary management goals included providing a nutritious and balanced diet, promoting, and maintaining healthy dietary habits, and symptomatic control.

The SDM-informed dietary intervention based on a digital health system was tailored to meet the needs of each patient during the dietary management. The intervention plan was developed focusing on dietary management goals, although other characteristics such as healthcare competence were also considered taking into account the clinical profile of patients and their priorities, interests, and preferences. The process of SDM based on digital health systems was developed collaboratively among professionals and patients by providing information, explaining the advantages and disadvantages, and promoting the active role of older adults with T2DM. Considering the connotation of SDM and the advantages of digital health system assistance, on the premise of achieving information exchange between professionals and patients, we have identified the five key elements in dietary management for digital health system-assisted SDM-informed intervention in this study. 14 The five key elements were (1) evaluate and identify dietary management goals, (2) health care professional team counsels a proposal strategy about patient's diet, (3) discuss strategies with patients, where T2DM patients have opportunities to make decisions regarding their preferences and interests, (4) deliver information, training, and feedback on selected goals, and (5) analyze planned objective.

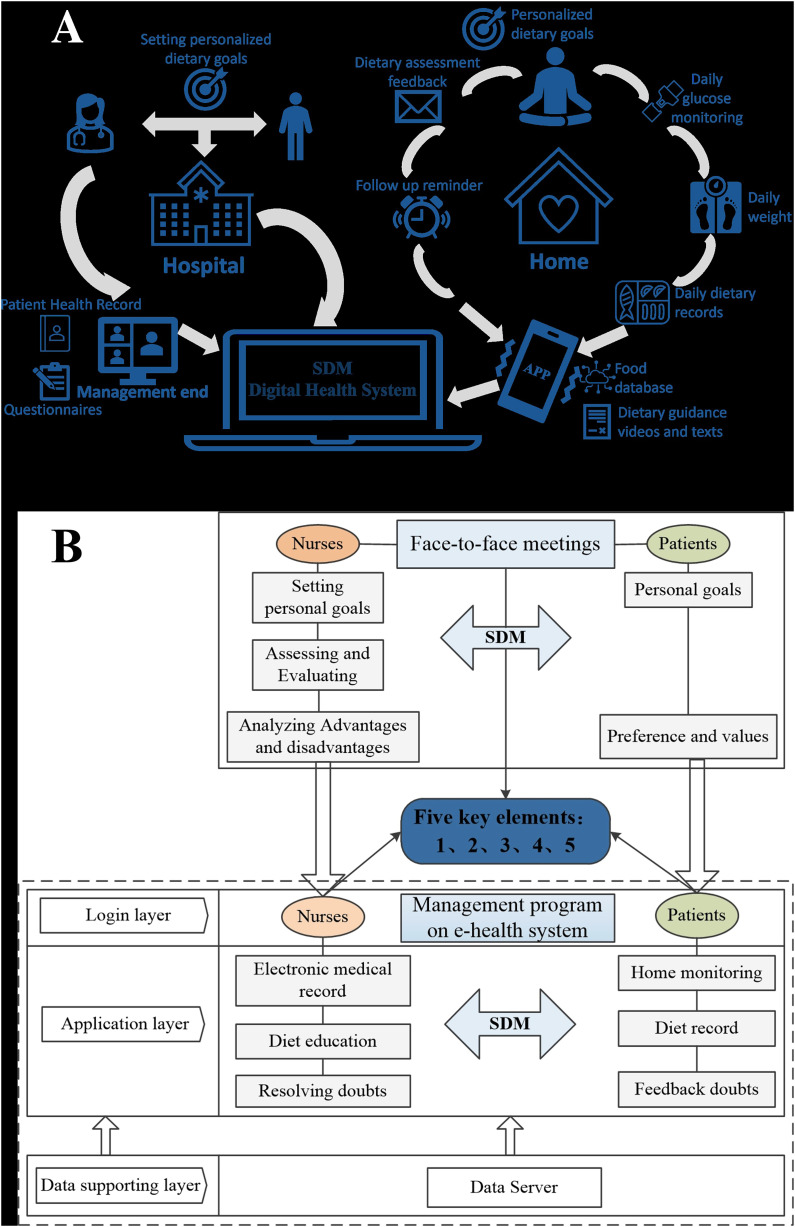

After clarifying the key elements, the SDM-informed dietary intervention assisted by the digital health system was achieved through a combination of online and offline methods, and the entire process includes two components: face-to-face meetings and a management program on the digital health system. The content of dietary management is jointly developed with each patient in the form of problem-solving, to detect potential erroneous beliefs, and to consider the best available evidence regarding the risks and benefits of each choice. This process is based on the three-talk model for SDM, 14 which consists of team talks, option talks, and decision talks, conducted during three face-to-face outpatient meetings. The digital health system is an important platform for implementing SDM-informed dietary intervention. One of its functions is to ensure and record information communication effectively between patients and nurses, and the other is to assist patients in daily dietary management.

Face-to-face meetingsThe face-to-face meetings between nurses and patients took place three times at T0 (baseline), T1 (one month after intervention), and T2 (three months after intervention) in an outpatient reception room. Face-to-face offline meetings were a complementary aspect of SDM assisted by digital health systems. Based on clear five key elements, nurses conducted interviews to understand the difficulties those patients encountered in the digital health system and provided information to patients to achieve their goals. Patients expressed their preferences and values in face-to-face meetings. At the same time, each face-to-face meeting was needed to complete the collection of patient outcomes and evaluated the completion of analysis goals. The content of each face-to-face evaluation, interview records, and personalized follow-up plans were recorded in the patient's digital health record by nurses and served as evidence for conducting dietary management plans.

Management program on digital health system

The management program on digital health systems was an SDM aid for nurses and patients to use together and exchange information during clinical consultations (see Supplemental Data). The digital health system-assisted SDM was carried out when needed by patients, which was unlimited by time and space. It provided a visual overview of medical, dietary, and behavioral data gathered by the individual. The data for participant home management can be manually entered by participants into mobile applications downloaded on their phones, such as blood glucose values, carbohydrate intake, or daily recipe. Nurses established digital health records for the intervention group in the digital health system. The nurses helped patients to download the mobile app of the digital health system on their mobile phones and taught them to use the dietary management function. The database of the mobile app stores over 10,000 common food information, and displays the calorie content of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in the food in units of 100 grams (see Appendix 1). During use, patients can complete the entry of home data by following the prompts on the application interface. After the patient selected the specific weight of the food, the mobile app automatically calculated calories for the patient to compare and exchange food calories. Nurses can view and evaluate patient usage through a digital management system that interacts with mobile applications (see Appendix 2). Nurses evaluate the dietary content of patients every week through the management procedure on the digital health system and send personalized diabetes diet-related knowledge to patients based on the dietary evaluation results. Patients uploaded daily dietary records every day for nurses to promptly understand the patient's dietary execution and to serve as evidence for optimizing and sharing dietary plans. Patients could consult nurses about their dietary management issues through the management program on the digital health system, and nurses could promptly address any issues raised by the patients (see Appendix 3). The diagrammatic sketch and framework of SDM-informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The diagrammatic sketch (a) and framework (b) of shared decision-making (SDM)-informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology.

Theoretical foundation

The information on dietary guidance for older adults with T2DM was collected from the guidelines for the prevention and management of T2DM in China,3,25 Chinese dietary guidelines for T2DM, 26 and the ADA website. The daily caloric intake calculated by nurses based on patient's weight, physical activity level, and disease condition is used as evidence-based evidence for dietary decisions. The actual dietary plan was based on calculated daily calories, and personalized daily recipe planning was carried out through the food exchange to ensure balanced nutrition for patients.

Control group

Standard dietary guidance and related health education were provided to the control group patients at T0, T1, and T2. (1) The patients were given routine care, and the knowledge of reasonable diet for diabetes was publicized. The patients were instructed to have regular and quantitative meals, avoid eating sweets, distribute diabetes diet publicity materials, and monitor blood glucose according to the doctor's instructions. (2) Nurses provided dietary guidance to patients based on their condition. (3) Nurses collected and analyzed the evaluation index for patients at follow-up, based on which, nurses helped older adults to realize the importance of diet management for diabetes.

Data collection

The trained researchers completed the outcome assessments. Sociodemographic and disease-related data were assessed at baseline. All outcomes were measured at baseline and after the intervention. The primary outcome measure was HbA1c. Secondary outcomes were physical indicators (body mass index (BMI), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and blood pressure) and self-care ability (diabetes self-management behavior and diabetes management self-efficacy). Considering the significance of changes in physical indicators (e.g. HbA1c and BMI) over time, physical indicators were only collected at baseline (T0) and three months after intervention (T2).

Except for physical indicators, self-care ability assessment was conducted through relative questionnaires in a quiet and spacious doctor-patient conversation room. If the older adults had difficulties in reading or writing, the data collector would read the questions to the subjects and record their responses. Questionnaire data were collected at three time points: baseline (T0), one month after intervention (T1), and three months after intervention (T2). Diabetes self-management behavior assessment was performed using the summary of diabetes self-care activities (SDSCA), with higher scores indicating greater self-care behaviors. The SDSCA has been shown to have good validity and reliability in both the original and Chinese versions, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.62 to 0.98.27,28 Self-efficacy for diabetes management was measured by Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (DMSES), with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy, 29 and has been shown with good validity and reliability, with Cronbach's alpha of 0.75 in the Chinese version. 30

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 software package. The categorical variables were represented by the number of cases and percentages, and the comparison between groups was conducted using the Pearson chi-square test. The measurement data conforming to normal distribution were expressed as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD), and two independent sample t-tests were used for inter-group comparison. Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to check compliance with normal distribution before the inter-group comparison of mean scores was performed. Multiple measurement indicators were analyzed using repeated measurement analysis of variance. All statistical significance tests were 2-sided, and the statistically significant was set at P = 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

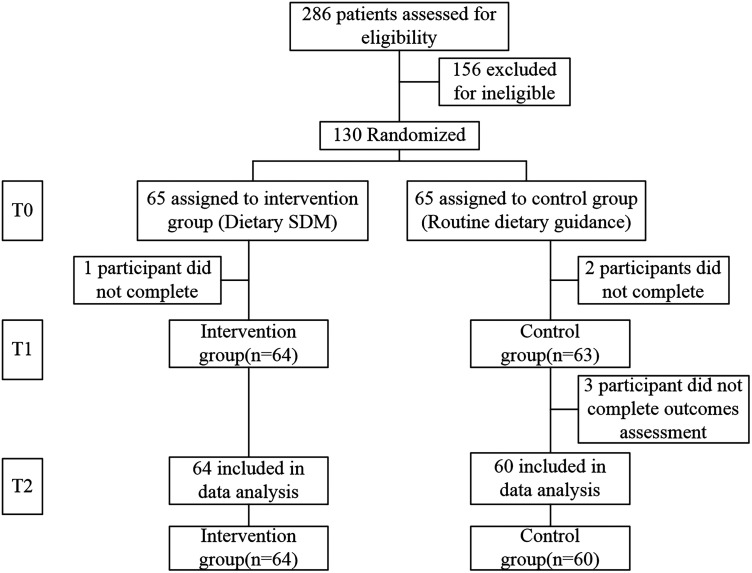

This study ultimately included 124 patients, 64 patients in the experimental group, and 60 patients in the control group. The recruitment process for participants is shown in Figure 2. A comparison of general information between the two groups is shown in Table 1. There was no statistical difference between the two groups in all variables. The mean age of the participants in the two groups was 66.77 and 67.38 years, respectively. On average, the participants had elevated glycemic control (HbA1c (%) = 8.09 and 8.16, respectively). The BMIs between the two groups were not significantly different despite falling marginally in two different obesity categorical groups, the intervention group (BMI = 23.9) was normal level (BMI = 18.5–23.9) and the control group (BMI = 24.65) was overweight (BMI = 24–27.9).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients in each group.

| Characteristics | Intervention | Control | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 64 | N = 60 | |||

| Age (years) | 66.77 ± 6.94 | 67.38 ± 5.79 | 0.536 | 0.593 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 38 (59.4) | 33 (55.0) | 0.242 | 0.623 |

| Female | 26 (40.6) | 27 (45.0) | ||

| Degree of education | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 46 (71.9) | 50 (83.3) | 2.333 | 0.311 |

| High school | 16 (25.0) | 9 (15.0) | ||

| University | 2 (3.1) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Vocation | ||||

| Worker | 19 (29.7) | 17 (28.3) | 0.328 | 0.988 |

| Houseworker | 8 (12.5) | 6 (10.0) | ||

| Farmer | 20 (31.2) | 19 (31.7) | ||

| Administrative or office personnel | 3 (4.7) | 3 (5.0) | ||

| Business or service personnel | 14 (21.9) | 15 (25.0) | ||

| Dining out frequency (Times/week) | ||||

| None | 58 (90.6) | 56 (93.3) | 0.440 | 0.932 |

| 1–2 | 2 (3.1) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| 3–4 | 3 (4.7) | 2 (3.3) | ||

| 5–6 | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Course of disease (years) | ||||

| <1 | 7 (10.9) | 7 (11.7) | 0.754 | 0.980 |

| 1–5 | 10 (15.6) | 11 (18.3) | ||

| 6–10 | 14 (21.9) | 14 (23.3) | ||

| 11–15 | 15 (23.4) | 14 (23.3) | ||

| 16–20 | 6 (9.4) | 6 (10.0) | ||

| >20 | 12 (18.8) | 8 (13.3) | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 8.09 ± 2.34 | 8.16 ± 1.96 | 0.183 | 0.855 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 10.24 ± 3.66 | 11.08 ± 3.83 | 1.251 | 0.213 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.90 ± 3.39 | 24.65 ± 3.22 | 1.252 | 0.213 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 130.02 ± 14.84 | 129.33 ± 11.48 | −0.285 | 0.776 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.44 ± 8.63 | 79.45 ± 6.86 | 0.009 | 0.993 |

| SDSCA | 34.72 ± 7.29 | 34.45 ± 7.38 | −0.204 | 0.839 |

| DMSES | 27.44 ± 2.96 | 27.37 ± 2.87 | −0.135 | 0.893 |

HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SDSCA: summary of diabetes self-care activities; DMSES: diabetes management self-efficacy scale.

Primary outcome

The comparison of HbA1c between groups after intervention is shown in Table 2. At baseline (Table 1), the primary outcome showed no significant differences between groups. After the intervention, there was a statistical difference in HbA1c between the two groups, and the improvement of HbA1c in the intervention group was superior to that in the control group (t = 3.298, P < 0.05). Compared to baseline, the intervention (8.09 ± 2.34 vs. 6.92 ± 1.03) and control (8.16 ± 1.96 vs. 7.58 ± 1.13) groups both showed a decrease in HbA1c, and the mean of HbA1c (6.92) decreased to normal level (<7%) in the intervention group after intervention.

Table 2.

Between-group comparison in the physical indicators after intervention.

| Physical indicators (M ± SD) | Intervention | Control | 95% CI | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 64 | N = 60 | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 6.92 ± 1.03 | 7.58 ± 1.13 | [0.28, 1.05] | 3.298 | 0.001* |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 7.38 ± 1.34 | 8.09 ± 1.27 | [0.25, 1.18] | 3.035 | 0.003* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.54 ± 3.28 | 24.60 ± 2.92 | [−0.05, 2.16] | 1.892 | 0.061 |

| SBP | 126.94 ± 10.46 | 127.60 ± 7.89 | [−2.65, 3.97] | 0.396 | 0.693 |

| DBP | 73.98 ± 7.41 | 79.43 ± 3.95 | [3.32, 7.58] | 5.060 | 0.000* |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; FPG: fasting plasma glucose; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

*P < 0.05.

Secondary outcomes

Physical indicators related to glycemic control

Table 2 presents the differences between the intervention and control groups in the secondary outcomes about physical indicators including FPG, BMI (body mass index), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Regarding the physical indicators, after the intervention, the mean value of the FPG was lower in the intervention group (7.38 ± 1.34) than in the control group (8.09 ± 1.27), and the difference between the two groups is statistically significant (t = 3.035, P = 0.003). Although the mean value of the FPG in the intervention group decreased three months after the intervention, it remained above the standard level (≥7 mmol/L). Regarding blood pressure, there was a statistically significant difference in DBP between the two groups three months after intervention (t = 5.060, P < 0.05). In addition, although both groups had a decrease in SBP compared to baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in SBP between the two groups after three months of intervention (t = 0.396, P = 0.693). Compared with baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in BMI between the two groups after three months of intervention (t = 1.892, P = 0.061), and there was no significant decrease in the mean BMI between the intervention group (23.90 ± 3.39 vs. 23.54 ± 3.28) and the control group (24.65 ± 3.22 vs. 24.60 ± 2.92).

Self-care ability

Table 3 presents the comparison of self-care ability scores between two groups. The results of repeated measurement analysis of variance showed that both SDSCA ((group) F = 34.165, P = 0.001; (time) F = 13.081, P < 0.001; (time × group interaction) F = 7.630, P < 0.001) and DMSES ((group) F = 25.299, P = 0.001; (time) F = 10.751, P = 0.004; (time × group interaction) F = 7.127, P < 0.001) scores of patients had time, group main effects, and time group interaction effects (P < 0.05). Further simple effect analysis was conducted, with time as the independent variable. The results showed that the SDSCA and DMSES scores were both higher than baseline at 1 month (T1) and 3 months (T2) after intervention (P < 0.05). The results of effect analysis using group as the independent variable showed that before intervention (T0), there was no statistically significant difference in all scale scores between the intervention group and the control group (P > 0.05), and at 1 month (T1) and 3 months (T2) after intervention, the SDSCA and DMSES scores of the intervention group were higher than those of the control group (P < 0.05). As time increases, self-care ability increased depending on the type of group. In addition, Appendix 4 presents the details of patient's daily dietary intake. Among the 64 participants in the intervention group, 34 (34 out of 64, 53%) participants achieved a 100% compliance rate and 61 (61 out of 64, 95%) participants achieved 90%. Supplemental Appendix 4 shows the satisfactory compliance rate of daily dietary intake for patients.

Table 3.

Comparison of self-care ability scores between two groups (M ± SD).

| Group | Self-management (SDSCA) | Self-efficacy (DMSES) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | |

| Control (n = 60) | 34.45 ± 7.38 | 35.12 ± 6.90 | 35.77 ± 8.36 | 27.37 ± 2.87 | 27.83 ± 2.94 | 27.65 ± 2.89 |

| Intervention (n = 64) | 34.72 ± 7.29 | 41.95 ± 7.78a,b | 43.02 ± 9.32a,b | 27.44 ± 2.96 | 29.61 ± 3.83a,b | 30.73 ± 3.26a,b |

| F value | F (time × group) = 7.630, F (group) = 34.165, F (time) = 13.081 | F (time × group) = 7.127, F (group) = 25.299, F (time) = 10.751 | ||||

| P-value | P (time × group) < 0.001*, P (group) = .001*, P (time) < 0.001* | P (time × group) < 0.001*, P (group) = 0.001*, P (time) = 0.004* | ||||

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; SDSCA: summary of diabetes self-care activities; DMSES: diabetes management self-efficacy scale.

Compared to baseline (T0), P < 0.05.

Compared to the control group, P < 0.05.

*P < 0.05.

Discussion

Discussion

This study considered older adults with T2DM as the participants, through a parallel double-arm randomized controlled trial, and evaluated the effectiveness of SDM-informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology among older adults with T2DM.

The main results of this study showed that the SDM-informed dietary intervention significantly improved patients’ glycemic control and self-care behavior. After three months of intervention, there were significant differences in HbA1c, FPG, DBP, self-management ability, and self-efficacy among each group, and the intervention group had a higher value. Therefore, these results proved that the SDM-informed dietary intervention based on a digital health system is effective for older adults with T2DM.

The ADA points out that the goal of diabetes diet management is to achieve and maintain a reasonable weight, 31 obtain good glycemic control, and blood pressure control, and delay the occurrence of diabetes complications. The older adults included in this study all have issues with poor glycemic control. The practice of SDM-informed dietary intervention pays attention to patients’ preferences, involves patients in dietary management, and provides patients with the necessary knowledge and skills, achieving education on patient dietary management behavior through information exchange. 32 A previous cluster randomized controlled trial 23 implemented patient-centered communication and joint decision-making for patients with poorly controlled T2DM. The results suggested that patients with poorly controlled T2DM were able to improve their blood glucose levels, but the study could not confirm the effectiveness of SDM-informed interventions compared with conventional care. In our study, we considered the demographic characteristics of older adults by being attuned to their needs in SDM and integrated face-to-face and digital health systems into SDM applications for patients’ dietary management, and the results showed that glycemic control was improved among older adults with T2DM. At the same time, the effectiveness of the intervention on glycemic control was confirmed compared to the control group. Regarding SDM-informed intervention based on a digital health system, Ruissen 33 developed and tested a digital health system to support SDM and diabetes self-management for patients and healthcare professionals. The advantages of SDM in the glycemic control of patients were verified, which was consistent with our study findings.

However, in our study, the effectiveness was not validated in the patient's BMI and SBP after three months of intervention. Although the weight level (M ± SD) at T2 in each group decreased compared with that at T0, there was no statistically significant difference in the weight between the two groups at T2, which may be related to having fewer people who were considered overweight at baseline. 34 Maintaining an ideal weight is an important goal of glycemic control in diabetes management. 31 Therefore, the long-term impact of the SDM-informed dietary intervention based on the digital health management system on weight control in older adults with T2DM still needs a longer intervention for verification.

The evaluation of self-management ability and self-efficacy of older adults with T2DM after intervention in this study found that the intervention had a significant effect on improving self-management ability and self-efficacy for patients. This finding is consistent with those of previous randomized controlled trials in patients with diabetes, lumbar degenerative diseases, and knee/hip osteoarthritis.35–37 In addition, the progress of self-management ability and self-efficacy in older adults with T2DM showed the effect that changed over time, which suggested that the SDM-informed dietary intervention based on the digital health management system in this study may be suitable as a long-term plan to improve self-care ability for older adults with T2DM. The model of dietary SDM in this study fully ensured information exchange between patients and medical professionals, which could help achieve patient education related to dietary management.34,38 People may be motivated to alter and maintain healthy behaviors if given health-related information and support. 39 The theory of knowledge, attitude/belief, and practice by Karbalaeifar explains that individuals learn and acquire knowledge and skills to enhance their health beliefs and attitudes, thereby contributing to the occurrence and maintenance of self-management behaviors. 40 After acquiring dietary management knowledge, older adults with T2DM were probably more likely to develop a positive attitude, which might facilitate the active formation of dietary management behaviors.41,42 The active dietary management behavior of older adults with T2DM will further help them achieve glycemic control goals.

In addition to the exchange of health information, we believe that the logging and self-monitoring functions reflect the multifaceted characteristics of the system, which is one of the main advantages of this digital health system, because it not only recognizes the complexity of diabetes care, but also conforms to the most advanced multifactorial care approach. 33 Through various functions, the system can collect information on various behaviors and medical aspects of personal self-management and intervene, ultimately improving glycemic control and self-care ability.

This study has several strengths. First, previous studies on the effect of SDM and digital health system in diabetes patients did not pay attention to the older adults, however, regarding past studies, one showed that the older adults have a higher demand for behavior change intervention with a foundation of SDM. 43 Second, the self-management ability of diabetes patients has great significance to the development and outcome of the disease. 44 This study measured the self-management ability of diabetes patients to consider the impact of SDM-informed dietary intervention and found that dietary intervention improved the self-management ability of older adults with T2DM, which was an outcome that was less concerned by previous studies on behavior change intervention with a foundation of SDM in diabetes patients. Finally, the implementation of a behavior change intervention with a foundation of SDM is complex, and the design of the intervention in this study integrated face-to-face and digital health technology to fully implement the core elements of SDM, which has reference significance for the application of SDM.

This study has some limitations. First, all the participants were recruited from a tertiary university hospital. They may not be representative of all older adults with T2DM. Therefore, the popularization of the study results is limited. Second, the nurses participating in the intervention plan all had specialized nurses who provided dietary interventions for older adults with T2DM. However, as is well known, compared to metropolitan areas, the medical resources and professional skills of nurses in rural and remote areas are limited. 16 The dietary management ability of nurses in different regions is uneven, which requires the development of communication skills and how to perform well in dietary intervention training. Third, we did not consider the impact of differences in the participants’ conditions on the results. We excluded patients with limited self-care ability due to their barriers and patients without the Internet. They could not cooperate with this study. We could not know their needs for dietary SDM based on the digital health system and the effectiveness of the intervention program on their health outcomes. Despite these limitations, our study was strictly designed and implemented, and the results clearly illustrated the clinical effect of the SDM-informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology on glycemic control and self-management behavior in older adults with T2DM.

Conclusion

The SDM-informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology for older adults with T2DM significantly improved patients’ glycemic control and enhanced self-management, and self-efficacy. This intervention can be a more efficient dietary management strategy for older adults with T2DM than the routine dietary management. In the future, further longitudinal studies can be conducted to explore the role of digital health management systems as auxiliary tools for behavior change intervention in maintaining the ideal weight and continuing care of older adults with T2DM.

Practical implications

The SDM-informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology seems to engage older adults with T2DM in decision-making. Practicing behavior change intervention with a foundation of SDM in the management of chronic diseases in older adults can improve the efficiency of communication and health education, help older adults improve their self-management ability and self-efficacy, and further help them achieve symptom control goals. In addition, clinicians are recommended to integrate digital health technology into face-to-face SDM, and the core components and communication model of SDM will be more fully implemented through digital health technology.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241272514 for The effects of shared decision-making informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial by Wei Zhang, Xiaoling Zhu, Xianfeng Que and Xiaoyi Zhang in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076241272514 for The effects of shared decision-making informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial by Wei Zhang, Xiaoling Zhu, Xianfeng Que and Xiaoyi Zhang in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge all the nurses from the endocrinology department and diabetes clinics at the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University.

Footnotes

Contributorship: WZ: Collected the data, prepared the figures and/or tables, drafted the paper, reviewed and revised the paper, and approved the final draft. XZ: Conceived the study, collected the data, analyzed the data, reviewed and revised the paper, and approved the final draft. XQ: Acquired funding for the study. Collected the data, analyzed the data, and approved the final draft. XZ: Collected the data, analyzed the data, and approved the final draft. All listed authors meet the authorship criteria and all authors agree with the content of the manuscript.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions, for example, they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and informed consent: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (No. 2023-K045-01). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients before the commencement of the trial. It was registered and approved by the China Clinical Trials Center (ChiCTR2300071455). https://www.chictr.org.cn/bin/project/edit?pid=197533

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Science and Technology Project of Nantong City (Grant no. MSZ2023071; Grant no. MS22022021), Jiangsu Provincial Hospital Association (Grant no. JSYGY-3-2023-155) and the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (Grant no. Tfh2203). The funding body had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or the writing of the manuscript. No other authors have received any grants related to this manuscript.

Guarantor: ZXY.

ORCID iD: Wei Zhang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5325-7657

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.WHO. Diabetes fact sheet, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (2022, accessed 18 November 2022).

- 2.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018; 138: 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinese Diabetes Society. Guideline for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China. Chin J Diabetes Mellitus 2021; 13: 315–409. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad E, Lim S, Lamptey R, et al. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2022; 400: 1803–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbanya JC, Lamptey R, Uloko AE, et al. African cuisine-centered insulin therapy: expert opinion on the management of hyperglycaemia in adult patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Ther 2021; 12: 37–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Lampousi AM, et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2017; 32: 363–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2022; 45: 2753–2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tada A, Miura H. Systematic review of the association of mastication with food and nutrient intake in the independent elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014; 59: 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu FL, Tai HC, Sun JC. Self-management experience of middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2019; 13: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aquino JA, Baldoni NR, Flôr CR, et al. Effectiveness of individual strategies for the empowerment of patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2018; 12: 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology – clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan – 2015. Endocr Pract 2015; 21(Suppl 1): 1–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 2015; 58: 429–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, et al. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014; 16: e12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elwyn G. Shared decision making: what is the work? Patient Educ Couns 2021; 104: 1591–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granados-Santiago M, Valenza MC, López-López L, et al. Shared decision-making and patient engagement program during acute exacerbation of COPD hospitalization: a randomized control trial. Patient Educ Couns 2020; 103: 702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne E, Palmer G, Rollo M, et al. Rural healthcare delivery and maternal and infant outcomes for diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review. Nutr Diet 2022; 79: 48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan C, Naughton C, Caples M, et al. Shared decision-making with adults transitioning to long-term care: a scoping review. Int J Older People Nurs 2023; 18: e12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinger K, Beverly EA, Smaldone A. Diabetes self-care and the older adult. West J Nurs Res 2014; 36: 1272–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont C, Smets T, Monnet F, et al. Publicly available, interactive web-based tools to support advance care planning: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2022; 24: e33320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun C, Sun L, Xi S, et al. Mobile phone-based telemedicine practice in older Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019; 7: e10664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2010; 1: 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmati Maslakpak M, Razmara S, Niazkhani Z. Effects of face-to-face and telephone-based family-oriented education on self-care behavior and patient outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Res 2017; 2017: 8404328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wollny A, Altiner A, Daubmann A, et al. Patient-centered communication and shared decision making to reduce HbA1c levels of patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus – results of the cluster-randomized controlled DEBATE trial. BMC Fam Pract 2019; 20: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzpatrick SL, Golden SH, Stewart K, et al. Effect of DECIDE (decision-making education for choices in diabetes everyday) program delivery modalities on clinical and behavioral outcomes in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 2149–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chinese Diabetes Society. Guideline for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China. Chin J Pract Intern Med 2018; 38: 292–344. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinese Nutrition Society. Chinese dietary guidelines for type 2 diabetes and interpretation. Acta Nutriment 2017; 39: 521–529. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang J, Wu T, Hu X, et al. Self-care activities among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Pract 2021; 27: e12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorig K, Ritter PL, Villa FJ, et al. Community-based peer-led diabetes self-management: a randomized trial. Diabetes Educ 2009; 35: 641–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun SN, Zhao WG, Dong YY, et al. The current status and influential factors of self-management in diabetic patients. Chin J Nurs 2011; 46: 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberlain JJ, Rhinehart AS, Shaefer CF, Jr, et al. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164: 542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 780–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruissen MM, Torres-Peña JD, Uitbeijerse BS, et al. Clinical impact of an integrated e-health system for diabetes self-management support and shared decision making (POWER2DM): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2023; 66: 2213–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Den Ouden H, Vos RC, Pieterse AH, et al. Shared decision making in primary care: process evaluation of the intervention in the OPTIMAL study, a cluster randomised trial. Prim Care Diabetes 2022; 16: 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey RA, Pfeifer M, Shillington AC, et al. Effect of a patient decision aid (PDA) for type 2 diabetes on knowledge, decisional self-efficacy, and decisional conflict. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Branda ME, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, et al. Shared decision making for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021; 104: 2498–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 1997; 44: 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao R, Guo H, Liu Y, et al. The effects of message framing on self-management behavior among people with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2023; 142: 104491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karbalaeifar R, Kazempour-Ardebili S, Amiri P, et al. Evaluating the effect of knowledge, attitude and practice on self-management in patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 2016; 53: 1015–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji H, Chen R, Huang Y, et al. Effect of simulation education and case management on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2019; 35: e3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chai S, Yao B, Xu L, et al. The effect of diabetes self-management education on psychological status and blood glucose in newly diagnosed patients with diabetes type 2. Patient Educ Couns 2018; 101: 1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schattner A. Sense and sensibility. Am J Med 2021; 134: 1570–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham AT, Crittendon DR, White N, et al. The effect of diabetes self-management education on HbA1c and quality of life in African-Americans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241272514 for The effects of shared decision-making informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial by Wei Zhang, Xiaoling Zhu, Xianfeng Que and Xiaoyi Zhang in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076241272514 for The effects of shared decision-making informed dietary intervention based on digital health technology in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial by Wei Zhang, Xiaoling Zhu, Xianfeng Que and Xiaoyi Zhang in DIGITAL HEALTH