Abstract

Background

The pragmatic role of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography (DCMRL) needs to be evaluated and compared across distinct lymphatic disorders. We aimed to evaluate the performance of DCMRL for identifying the underlying causes of lymphatic disorders and to define the potential benefit of DCMRL for planning lymphatic interventions.

Methods

Patients who underwent DCMRL between August 2017 and July 2022 were included in this retrospective analysis. DCMRL was performed with intranodal injection of a gadolinium-based contrast medium through inguinal lymph nodes under local anesthesia. Technical success of DCMRL and feasibility of percutaneous embolization were assessed based on the lymphatic anatomy visualized by DCMRL. Based on the underlying causes, clinical outcomes were evaluated and compared.

Results

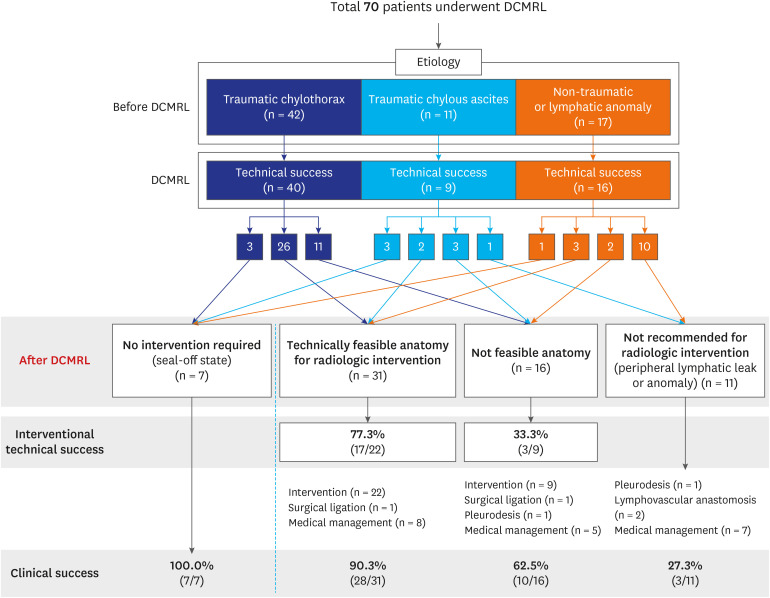

Seventy consecutive patients were included. The indications were traumatic chylothorax (n = 42), traumatic chylous ascites (n = 11), and nontraumatic lymphatic leak (n = 17). The technical success rate of DCMRL was the highest in association with nontraumatic lymphatic disorders (94.1% [16/17]), followed by traumatic chylothorax (92.9% [39/42]) and traumatic chylous ascites (81.8% [9/11]). Thirty-one (47.7%) patients among 65 patients who underwent technically successful DCMRL had feasible anatomy for intervention. Clinical success was achieved in 90.3% (28/31) of patients with feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention, while 62.5% (10/16) of patients with anatomical challenges showed improvement. Most patients with traumatic chylothorax showed improvement (92.9% [39/42]), whereas only 23.5% (4/17) of patients with nontraumatic lymphatic disorders showed clinical improvement.

Conclusion

DCMRL can help identify the underlying causes of lymphatic disorders. The performance of DCMRL and clinical outcomes vary based on the underlying cause. The feasibility of lymphatic intervention can be determined using DCMRL, which can help in predicting clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Lymphangiography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Chylothorax, Thoracic Duct

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Lymphatic leakage, which presents as chylothorax or chylous ascites, is a rare complication stemming from either lymphatic trauma or nontraumatic causes.1,2 It could be fatal due to its potential to cause malnutrition, loss of fluid and immune cells, and electrolyte imbalance, along with its potential to act as a reservoir for infection.2,3 Therefore, accurate identification of lymphatic anatomy and underlying pathogenesis is essential for their management.

Conventional intranodal lymphangiography (CL) has been used to imaging modality for anatomic evaluation and diagnosis of lymphatic disorder, but it involves exposing patients to ionizing radiation.2 In contrast to CL, dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography (DCMRL) can show lymphatic anatomy and flow dynamics in high resolution, which aids in identifying the underlying cause without the associated risks.4,5,6 However, due to the rarity of lymphatic diseases and the limited availability of MR imaging, the application of DCMRL in patients with lymphatic diseases and their outcomes have been investigated only in a few case series,5 especially in pediatric patients.5,6,7,8

The clinical usefulness of contrast-enhanced interstitial transpedal magnetic resonance lymphangiography (MRL)9 and noncontrast MRL10 in chylothorax has been reported. However, these techniques have limitations, such as challenges in capturing the adequate enhancement time or a lack of dynamic information on lymphatic leakage. DCMRL could be a useful method to compensate for these drawbacks. We performed DCMRL on adult patients with suspected lymphatic disorders of various origins before deciding on the required lymphatic intervention. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the performance of DCMRL in identifying various causes and delineate the advantages of DCMRL in assessing the feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention.

METHODS

Study population

Patients who underwent DCMRL between August 2017 and July 2022 were included in this retrospective analysis. DCMRL was performed for diagnosis and interventional planning for patients with chylothorax, chylous ascites, or lymphatic dysfunction or anomalies, by identifying the leakage site or underlying anatomy of the central lymphatics. Among these patients, 22 with traumatic chylothorax were included in a previous study that investigated imaging findings and clinical outcomes after lung cancer surgery.11 In contrast to the previous study, which focused exclusively on traumatic chylothorax after lung cancer surgery, the present study evaluated characteristics in a broader spectrum of lymphatic disorders

Data pertaining to patients’ demographics, anthropometrics, underlying diseases, history of surgery and lymphatic interventions, and medical and interventional management for lymphatic disorders were thoroughly reviewed from electronic medical records. Chylothorax or chylous ascites was diagnosed when the concentration of triglycerides was considerably high (> 100 mg/dL) or lymphocytes predominated (> 70%) in the drainage fluid.

DCMRL

DCMRL was performed using a 3-T MR machine (Ingenia; Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). The patients were placed supine on an MR-compatible table in an ultrasound room. Under local anesthesia with lidocaine injections administered subcutaneously in both inguinal areas, expert cardiovascular radiologists (H.J.K. with 12 years of experience in cardiovascular imaging) used a 26-gauge spinal needle into the medulla of both inguinal lymph nodes under ultrasonographic guidance. The patient table was then moved to the MR room and placed in the gantry. Then, T2-weighted turbo spin-echo fat saturation sequence (optional) and free breath dynamic T1-weighted high-resolution imaging with volumetric excitation (THRIVE) images of the entire chest and abdomen were obtained. The T2-weighted images were obtained using the following acquisition parameters: repetition time/echo time, 1,744.8/650.0 ms; flip angle, 90°; Cartesian k-space acquisition; and field of view, 340.0 mm. The THRIVE sequence parameters were as follows: repetition time/echo time, 3.0/1.5 ms; flip angle, 15°; field of view, 340.0 mm; and acquisition time, approximately 1 minute. After obtaining unenhanced THRIVE sequences, 2–3 mL of a 1:1 mixture of a contrast material (Gadovist®, gadobutrol [1 mL/10 kg]; Bayer Inc., Leverkusen, Germany; Dotarem, gadoteric acid - gadoterate meglumine [2 mL/10 kg]; Guerbet, Roissy, France) and saline was manually injected (1–2 mL/min) through a needle with a short connector. Typically, the dynamic contrast-enhanced image was acquired 2–3 minutes after the start of the contrast injection. However, if the contrast material did not reach the retroperitoneal lymphatics due to sluggish flow, an additional delay of 1–2 minutes was allowed. In such cases, the start time of the scan depended on the lymphatic flow. Three to five enhanced THRIVE sequences were obtained thereafter, continuing until the cisterna chyli and thoracic duct were visualized. If the lymphatic flow was too slow and only faintly visible, additional contrast material was injected, and further THRIVE sequences were acquired.

Definitions

Lymphatic dysfunction broadly refers to an impairment of the lymphatic system’s unidirectional circulatory network, arising from either congenital defects or acquired damage to the lymphatic vessels. Of them, we separate the iatrogenic “traumatic chylothorax” and iatrogenic “traumatic chylous ascites” to distinct category, hereafter. DCMRL was considered technically successful if the central lymphatic structures, including the retroperitoneal lymphatics and thoracic duct, were opacified, with or without lymphatic leakage or any abnormal lymphatic structures (such as collateral formation) being opacified. Conversely, it was classified as technically unsuccessful if the central lymphatics, extending from the pelvic and abdominal retroperitoneal lymphatics to the thoracic duct, were not visible despite the administration of contrast media or if systemic venous contamination impeded the evaluation of lymphatic structures. An exception to this was the nonvisualization of central lymphatics due to a congenital lymphatic anomaly, which was considered a technical success. Feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention is defined when lymphatic leakage was present on DCMRL and either when a prominent cisterna chyli was identified (with a diameter more than twice that of the thoracic duct) or when the leakage site was accessible by direct needle puncture or with a microcatheter without any disruption en route. On the other hand, the intervention was deemed not applicable when the central lymphatics were absent or if the route to the leakage site was obliterated due to previous lymphatic interventions or surgery. Technical success of the lymphatic intervention was defined as cessation of contrast extravasation on post-procedural lymphangiography or occlusion of the target lesion. Clinical success was classified into improved (cessation of lymphatic leakage and removal of the drainage tube) or partially improved (reduction in lymphatic leakage with a beneficial effect on the clinical course). Clinical failure was declared when lymphatic leakage persisted without any signs of improvement.

MRL image analysis

DCMRL images were reviewed and discussed by two cardiovascular radiologists (Y.A. and H.J.K., with 6 and 12 years of experience in cardiovascular imaging, respectively) until a consensus was reached. Using the enhanced THRIVE sequences, the entire course of the thoracic duct was assessed. For post-processing, maximal intensity projection and volume rendering images were generated. The site of lymphatic leakage was identified as the area from where the contrast media deviated from the expected course of the central lymphatics. Additionally, the course of the thoracic duct and any anomalies in the central lymphatics were documented. The presence of pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, or ascites was assessed on T2-weighted images. The location and diameter of the cisterna chyli were determined using axial- and coronal-reconstructed enhanced THRIVE images for assessing the potential route of the transabdominal approach in subsequent lymphatic interventions.

Intranodal lymphangiography and lymphatic intervention

Lymphatic interventional procedures were performed by two experienced interventional radiologists (H.H.C. and J.H.S.). CL was performed via inguinal node cannulation by administering 10–20 mL of ethiodized oil (Lipiodol; Guerbet). Fluoroscopic spot images were acquired every 5 minutes after ethiodized oil injection. For traumatic chylothorax, thoracic duct embolization was performed via the percutaneous transabdominal approach when the thoracic duct or a lymphatic structure that was large enough to be considered for percutaneous access (i.e., cisterna chyli) were visualized using CL. Otherwise, the retrograde approach through the left subclavian vein, or direct access into the leakage site was performed. After embolization with or without the use of 2–4 mm of detachable fibered coils (Concerto coil [Covidien, Plymouth, MN, USA] or Interlock coil [Boston Scientific, Cork, Ireland]) or pushable coils (Tornado or MicroNester coils; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA), N-butyl-2- cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl Blue; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was used as the embolic agent. In cases of traumatic chylous ascites, CL and adjunctive glue embolization were performed to address lymphatic leakage. This was achieved either through the embolization of lymphatic pseudoaneurysms or by targeting the nearest upstream lymph node or lymphatic vessel.12 For nontraumatic lymphatic disorders, thoracic duct embolization or direct percutaneous embolization techniques were used.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the independent t test or analysis of variance. For nonnormally distributed variables, the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The success rates for identification of lymphatic pathology, the thoracic duct, and the cisterna chyli according to the underlying cause of the lymphatic disorder were compared using the McNemar test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). P values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Ethics statement

This retrospective study protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center, and the requirement for written informed consent was waived (approval number: 2021-1832).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Seventy consecutive patients (mean age, 57.96 ± 14.76 years, 44 men [62.9%]) with traumatic chylothorax (n = 42), traumatic chylous ascites (n = 11), or nontraumatic lymphatic disorders (n = 17) were included (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The single most common underlying cause of traumatic chylothorax was lung cancer (52.4% [22/42]), which occurred most commonly after lung cancer surgery. Esophageal surgery was the second most common cause (31.0% [13/42]), followed by cardiovascular surgery (11.9% [5/42]). Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the pancreas was the most common cause of traumatic chylous ascites (27.3% [3/11]). Patients with nontraumatic lymphatic disorders demonstrated various clinical manifestations. The most common finding was the coexistence of chylothorax and chylous ascites (n = 8), followed by lymphedema (n = 5), chylothorax alone (n = 3), and chylous ascites alone (n = 1). Additionally, these patients had underlying diseases such as lymphoma (n = 2) or liver cirrhosis (n = 2). The interval between a prior operation and the onset of lymphatic pathology was shorter in association with traumatic chylothorax (median, 4 days) than with traumatic chylous ascites (median, 10 days).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of patient categorizations by underlying causes, treatment strategies, and clinical outcomes based on DCMRL results.

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography.

Table 1. Patient characteristics by cause of lymphatic disorder.

| Characteristics | Traumatic (n = 53) | Nontraumatic (n = 17) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chylothorax (n = 42) | Chylous ascites (n = 11) | ||||

| Age, yr | 63.05 ± 9.96 | 60.73 ± 12.92 | 43.59 ± 16.98 | < 0.001 | |

| Men | 32 (76.2) | 6 (54.5) | 6 (35.3) | 0.011 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.54 ± 2.98 | 20.74 ± 2.79 | 22.80 ± 7.43 | 0.434 | |

| Underlying diseases | |||||

| Lung cancer | 22 (52.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Esophageal cancer or stricture | 13 (31.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Pancreas cancer | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Lymphoma | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Sclerosing mesenteritis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Other tumorous conditiona | 2 (4.8) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (14.3) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Lymphatic dysfunctionb | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (64.7) | ||

| Prior operation | |||||

| Pneumonectomy | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | - | ||

| Lung lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection | 20 (47.6) | 0 (0.0) | - | ||

| Pleurectomy or diaphragm and pericardial resection | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | - | ||

| Ivor Lewis or McKeown operation | 13 (31.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | ||

| Thoracic aorta surgery or CABG | 5 (11.9) | 1 (9.1) | - | ||

| PPPD | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | - | ||

| Other operationc | 1 (2.4) | 5 (45.5) | - | ||

| Interval between prior operation and onset of lymphatic leak, day | 4 (1–12) | 10 (6–18) | - | 0.146 | |

| Prior lymphatic intervention | |||||

| Ethiodized oil lymphangiography | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Lymphatic embolization | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | ||

| Pleurodesis | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Initial management | |||||

| Drainage tube insertion | 42 (100.0) | 7 (63.6) | 10 (62.5) | < 0.001 | |

| Diet modulation (medium-chain triglyceride diet) | 40 (95.2) | 11 (100.0) | 11 (68.8) | 0.002 | |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 22 (53.7) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (25.0) | 0.140 | |

| Somatostatin/octreotide | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (13.3) | 0.191 | |

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%), or median (interquartile range).

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft, PPPD = pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy.

aIncluding malignant mesothelioma, primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma, paraganglioma, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and thyroid cancer.

bIncluding lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Noonan syndrome, clinically diagnosed lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome, and lymphatic anomaly.

cIncluding mediastinal mass excision via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, modified radical mastectomy, caesarean delivery, right nephrectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, total thyroidectomy, right nephrectomy, bilateral nephrectomy with kidney transplantation, retroperitoneal tumor excision, laparoscopic left salpingo-oophorectomy, and laparoscopic right hemicolectomy.

The DCMRL scan duration ranged from 34–36 minutes, less than half the time required for CL (range, 79–150 minutes), including the duration of subsequent lymphatic intervention. The required radiation dose for CL in terms of total air kerma and total dose area product was higher in association with traumatic chylothorax (mean, 805.9 mGy and 6,710.9 uGym2, respectively) and nontraumatic lymphatic disorders (mean, 734.4 mGy and 7,054.8 uGym2, respectively) than for traumatic chylous ascites (mean, 560.0 mGy and 3,788.9 uGym2, respectively).

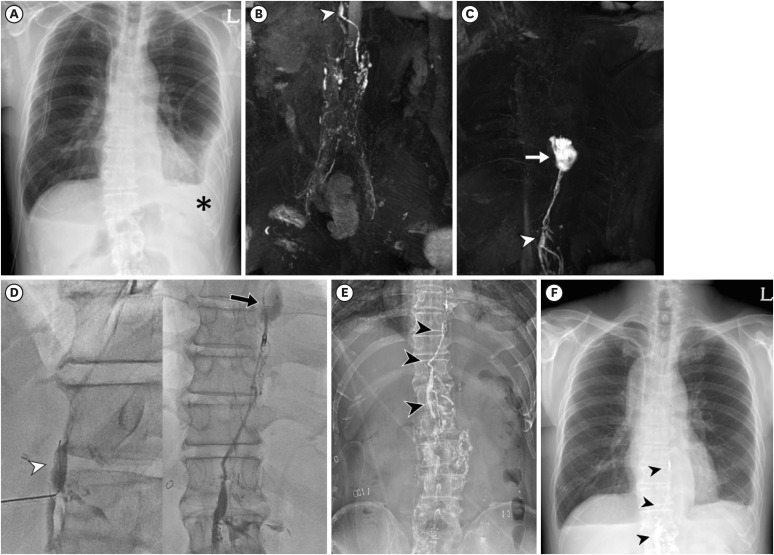

DCMRL for traumatic chylothorax

In traumatic chylothorax cases, DCMRL identified extravasation of contrast media in 85.7% (36/42) of patients, while CL identified it in 64.0% (16/25) of patients (Table 2, Fig. 2). DCMRL failed to facilitate visualization of the central lymphatics in 7.1% (3/42) of patients, whereas CL was associated with a higher technical failure rate (28.0% [7/25]) (P = 0.003). The thoracic duct was successfully visualized in most patients with traumatic chylothorax using DCMRL (92.9% [39/42]), and the success rate with DCMRL was greater than that with CL (68.0% [17/25]) (P = 0.008). The cisterna chyli was identified in 78.6% (33/42) of the patients who underwent DCMRL and 50% (13/25) of the patients who underwent CL. Of the 42 patients, 11 (26.2%) underwent CL and 12 (28.6%) underwent thoracic duct embolization. The clinical success rate was 92.0% (39/42), which was highest among the three etiologic categories (Table 3).

Table 2. Efficacy of MRL in depicting the underlying cause and anatomic details of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli.

| Parameters | Traumatic chylothorax (n = 42) | Traumatic chylous ascites (n = 11) | Nontraumatic (n = 17) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRL (n = 42) | CL (n = 25) | P value | MRL (n = 11) | CL (n = 6) | P value | MRL (n = 17) | CL (n = 8) | P value | |||

| Identified pathology | |||||||||||

| Normal central lymphatics (or sealed-off leak) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Thoracic duct injury | 36 (85.7) | 16 (64.0) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Abdominal lymphatic injury | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||||

| Lymphatic obstruction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (12.5) | |||||

| Lymphatic dysfunction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (82.4) | 7 (87.5) | |||||

| Technical failure | 3 (7.1) | 7 (28.0) | 0.003a | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | - | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | - | ||

| Thoracic duct visualization | 39 (92.9) | 17 (68.0) | 0.008a | 8 (72.7) | 3 (50.0) | 1.000a | 8 (47.1) | 2 (25.0) | 0.07a | ||

| Cisterna chyli identification | 33 (78.6) | 13 (52.0) | 0.10a | 6 (54.5) | 2 (33.3) | 0.45a | 8 (47.1) | 2 (25.0) | 0.07a | ||

| Location | |||||||||||

| T10–T11 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (4.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| T12–L1 | 12 (28.6) | 8 (32.0) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (25.0) | |||||

| L1–L2 | 19 (45.2) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (27.3) | NA | 6 (35.3) | NA | |||||

| Size, mm | 5.08 ± 1.39 (2.0–7.6) | 4.13 ± 1.72 (2.0–6.8) | 0.045 | 6.3 ± 2.4 (3.7–10.2) | 5.8 ± 2.5 (4.1–7.6) | NAb | 4.8 ± 1.8 (2.7–8.3) | 6.6 ± 1.6 (5.5–7.7) | NAb | ||

| Average scan time (procedure time), minc | 35 ± 27 (12–151) | 81 ± 27 (41–120) | < 0.001 | 34 ± 9 (21–47) | 84 ± 47 (44–175) | 0.031 | 36 ± 7 (24–48) | 150 ± 149 (36–491) | 0.004 | ||

| Total air kerma, mGy | NA | 805.9 ± 822.2 (139.0–3,836.0) | NA | 560.0 ± 400.4 (126.0–1,201.0) | NA | 734.4 ± 1,151.7 (93.6–3,277.0) | |||||

| Total dose area product, uGym2 | NA | 6,710.9 ± 6,260.8 (1,607.9–26,840.0) | NA | 3,788.9 ± 2,760.5 (1,514.5–8,448.4) | NA | 7,054.8 ± 10,955.5 (1,125.7–31,529.0) | |||||

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as number (%) of patients or mean ± standard deviation (range).

MRL = magnetic resonance lymphangiography, CL = conventional intranodal lymphangiography, NA = not applicable.

aResults of McNemar test.

bDue to small sample size (n = 2 for CL).

cResults of paired t test.

Fig. 2. A 58-year-old man developed bilateral chylothorax 4 days after an Ivor-Lewis operation for esophageal cancer. The chylothorax, refractory to diet modulation, produced a drainage of 1,100 mL/day. (A) Chest radiograph on the same day showed left pleural effusion (asterisk). (B) DCMRL on postoperative day 12: coronal 3-dimensional T1-weighted image with thin minimal intensity projection reconstruction 8 minutes after intranodal contrast injection revealed retroperitoneal lymphatics and cisterna chyli (arrowhead) at the T12 vertebral level. (C) Contrast leakage from the thoracic duct at the T8 vertebral level (arrow) 7 minutes post-injection. (D) Pre-intervention DCMRL indicated feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention with an accessible central lymphatic route; thoracic duct embolization was performed 2 days later via direct cisterna chyli puncture (arrowhead). The leakage, consistent with DCMRL findings, was located at T8/9 (arrow) and managed with one microcoil and N-butyl cyanoacrylate. (E) Post-embolization plain abdominal radiograph showing embolic materials (arrowheads) along retroperitoneal lymphatics and the thoracic duct. (F) Chest radiograph 3 days post-embolization showed reduced left pleural effusion and persistent embolic materials along the thoracic duct (arrowheads).

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography.

Table 3. Clinical outcomes after DCMRL by cause of lymphatic disorder.

| Details | Traumatic chylothorax (n = 42) | Traumatic chylous ascites (n = 11) | Nontraumatic (n = 17) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic intervention | 0.871a | ||||

| None | 17 (40.5) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (35.3) | ||

| Ethiodized oil lymphangiography only | 11 (26.2) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (17.6) | ||

| Thoracic/central duct embolization | 12 (28.6) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Surgical thoracic duct ligation | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Lymphovenous anastomosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Pleurodesis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Othersb | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Improvement in chylous fluid leak | < 0.001c | ||||

| Improved (clinical success) | 39 (92.9) | 7 (63.6) | 4 (23.5) | ||

| Partially improved | 2 (4.8) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (35.3) | ||

| Failed | 1 (2.4) | 3 (27.3) | 7 (41.2) | ||

| Interval between MRL and removal of drainage tube, day | 5.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 4.0 (2.5–18.0) | 0.971 | |

| Interval between intervention and removal of drainage tube, day | 4.5 (3.0–8.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 5.0 (2.0–15.5) | 0.939 | |

| Interval between MRL and hospital discharge, day | 7.0 (5.0–15.0) | 8.0 (6.0–19.0) | 7.0 (2.0–19.0) | 0.560 | |

| Repeat lymphatic intervention | 4 (9.5) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (17.6) | 0.294 | |

| Patient survival | 37 (88.1) | 10 (90.9) | 17 (100.0) | 1.000 | |

Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as number (%) of patients or median (interquartile range).

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography, MRL = magnetic resonance lymphangiography.

aThe χ2 test for comparison among no intervention, ethiodized oil lymphangiography, and thoracic/central duct embolization.

bIncluding direct leak site embolization via chest tube and sclerotherapy.

cFor comparisons between both (improved or partially improved vs. failed) and (improved vs. partially improved or failed).

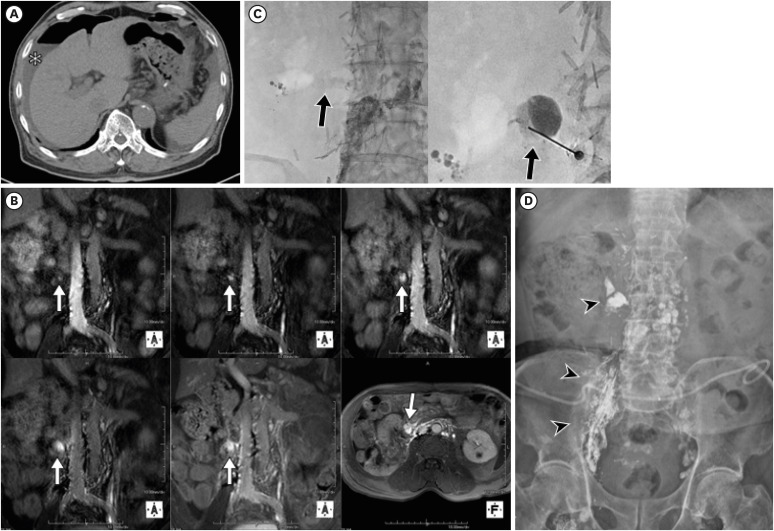

DCMRL for traumatic chylous ascites

For patients with traumatic chylous ascites, DCMRL identified the cause in less than half of the patients (45.5% [5/11]), and central lymphatics could not be observed in 27.3% (3/11) patients. CL identified the cause in 83.3% (5/6) of patients with an injury of central lymphatics without technical failure. The success rates for visualization of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli by DCMRL were 72.7% (8/11) and 54.5% (6/11), respectively, while those associated with CL were 50% (3/6) and 33.3% (2/6), respectively. Lymphatic intervention or CL was performed in 54.5% (6/11) of patients (Fig. 3), and only 63.6% (7/11) showed clinical improvement.

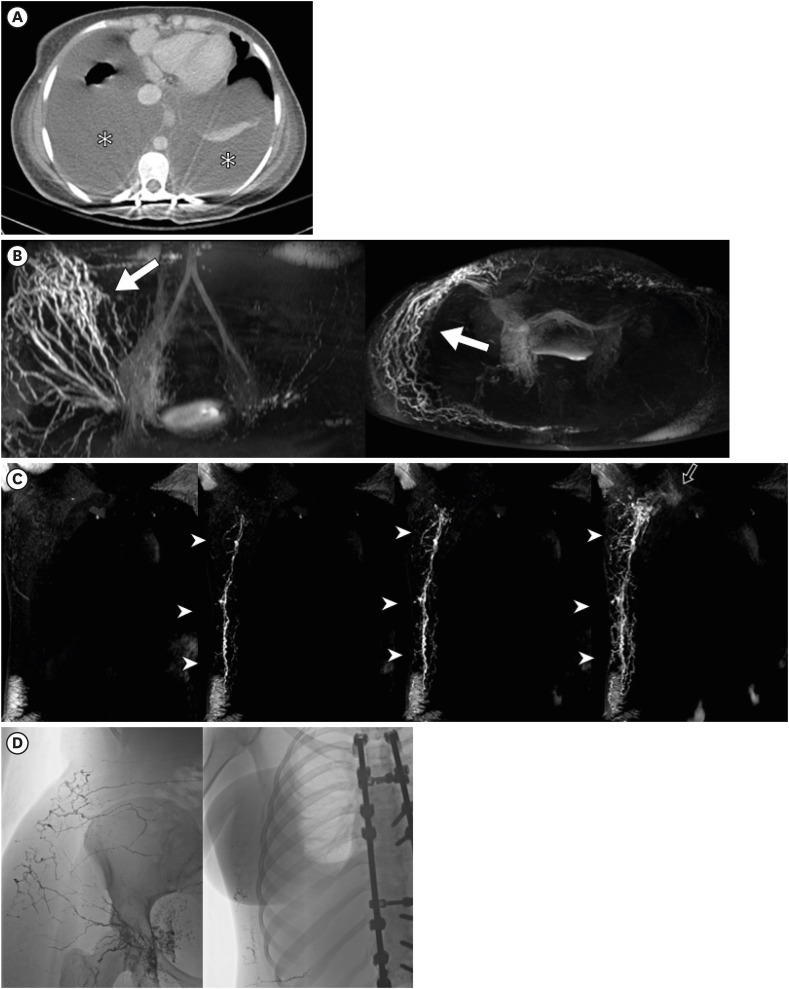

Fig. 3. A 73-year-old man presented with refractory chylous ascites 3 months after right nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. (A) Abdominal computed tomography illustrated perihepatic ascites (asterisk) with pneumoperitoneum due to therapeutic thoracentesis. (B) DCMRL performed after 2.5 postoperative years: coronal 3-dimensional T1-weighted images at 4, 6, 7, 10, and 16 minutes after intranodal contrast injection showed progressive contrast leakage (arrows) at the right inferior vena cava at L3. The axial image at 16 minutes post-injection showed contrast media leakage (white arrow) from retroperitoneal lymphatics. (C) Owing to the complex retroperitoneal lymphatics, the anatomy was considered technically unsuitable for intervention. The following day, conventional lymphangiography hinted at a faint leak (arrow), prompting direct puncture and N-butyl cyanoacrylate embolization. (D) One day post-intervention, plain abdominal radiography revealed ethiodized oil along retroperitoneal lymphatics and the leakage site. Despite this and three subsequent embolizations, the ascites did not resolve.

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography.

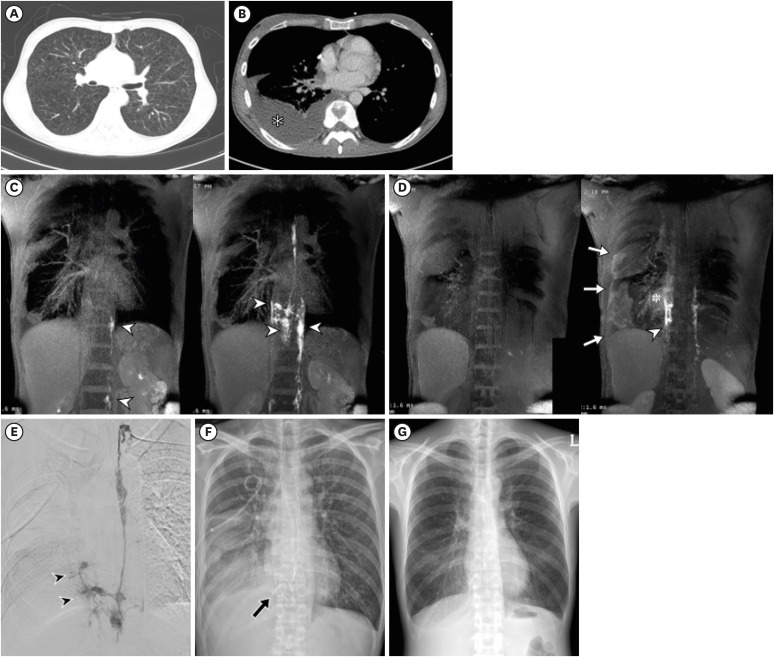

DCMRL for nontraumatic lymphatic disorders

Regarding nontraumatic lymphatic disorders, both DCMRL and CL successfully identified the causes in 94.1% (16/17) of patients. These included primary lymphatic dysfunction (nine congenital lymphatic anomalies and two lymphangioleiomyomatoses) or secondary lymphatic dysfunction (two liver cirrhosis, two lymphomas, and one sclerosing mesenteritis). The thoracic duct and cisterna chyli were visualized by DCMRL in less than half of the patients (47.1% [8/17]) who had nontraumatic lymphatic disorders, reflecting anomalies or dysfunction in the lymphatic drainage system. In detail, the findings of DCMRL consisted of lymphatic reflux or collateral formation (n = 8) and normal central lymphatics without leakage (n = 6). With CL, these structures were identified in only 25% [2/8] of patients. Clinical success was achieved in only 23.5% (4/17) of patients, which was the lowest among the three etiologic categories investigated, despite the highest rate of lymphatic intervention (64.7% [11/17]) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. A 34-year-old woman diagnosed with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. (A) Chest CT displayed numerous small cysts throughout both lungs, consistent with the underlying diagnosis. (B) CT scan 2 weeks prior to DCMRL revealed a newly developed right pleural effusion (white asterisk), confirmed as chylothorax by thoracic fluid analysis. (C) DCMRL was conducted with coronal 3-dimensional T1-weighted images using thin, minimal intensity projection reconstruction, showing retroperitoneal lymphatics (white arrowheads) 4 minutes after intranodal contrast injection (left), as well as tortuous, engorged lymphatic enhancement along the distal thoracic duct and right paravertebral area (white arrowheads) 9 minutes post-injection (right). (D) Following contrast medium injection, minimal intensity projection reconstruction at 20 minutes also showed an engorged lymphatic structure in the right paravertebral area (white arrowhead) with adjacent contrast leakage (black asterisk) and diffuse enhancement along the pleura (white arrows), indicating leakage from the anomalous lymphatic structure. The absence of a cisterna chyli or any other retroperitoneal lymphatic structure of sufficient caliber for guidewire navigation deemed this anatomy technically infeasible for intervention. (E) Consequently, conventional lymphangiography was performed 1 week post-DCMRL via a retrograde approach from the left subclavian vein, corroborating DCMRL findings of leakage from the anomalous structure (black arrowheads). Embolization used a microcoil and N-butyl cyanoacrylate. (F) Chest radiograph immediately post-embolization showed embolic materials in the right paravertebral area (black arrow) and draining right pleural effusion. (G) Over 3 months post-intervention, the right pleural effusion gradually resolved.

CT = computed tomography, DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography.

Fig. 5. An 18-year-old woman presented with bilateral leg edema for 10 years. She underwent lymphovenous and lymph node-to-vein anastomosis in bilateral inguinal, pretibial, and foot areas. (A) Despite these operations, chest computed tomography 1 month before DCMRL showed bilateral pleural effusion (asterisks), confirmed as chylothorax. (B) DCMRL indicated that contrast media did not travel through the central retroperitoneal and abdominal lymphatics but through abnormally dilated lymphatics in the right pelvic wall. Coronal (left) and axial (right) 3D T1-weighted images with thin maximal intensity projection at the pelvic level demonstrated a tortuous, engorged lymphatic structure along the right pelvic wall (white arrow). (C) Coronal 3D T1-weighted images with maximal intensity projection before and 7, 8, and 10 minutes after contrast medium injection revealed progressive enhancement of abnormal tortuous lymphatic structures along the right thoracoabdominal wall (white arrowheads), draining into the right subclavian vein (black arrow). The retroperitoneal lymphatics and thoracic duct were not discernible. Based on DCMRL findings, the patient was diagnosed with a central lymphatic flow disorder. As no accessible route for embolization to address the chylothorax was present, the anatomy was considered technically infeasible for intervention. (D) Conventional lymphangiography 3 weeks post-DCMRL mirrored the DCMRL findings, displaying prominent lymphatics along the abdominal and chest walls (left) and the absence of normal central lymphatics (right). Due to persistent chylothorax and the lack of feasible anatomy for intervention, the patient ultimately underwent right pleurodesis 3 months after DCMRL, which partially ameliorated the chylothorax.

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography, 3D = 3-dimensional.

Diagnostic accuracy of DCMRL

The concordance rate of finding (i.e., leakage, normal central lymphatics [or sealed-off leak], and lymphatic obstruction of dysfunction) between DCMRL and CL was evaluated in the 32 of 70 patients, who underwent radiologic lymphatic intervention, including or exclusively with CL, and excluded those with technical failures in obtaining the CL. The concordance rate was 31/32 (96.9%). In one case, the DCMRL failed to identify the leakage (Table 4).

Table 4. Concordance between DCMRL and CL (32 of 70 patients).

| DCMRL | CL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic leakage | Normal central lymphatics (or sealed-off leak) | Lymphatic obstruction or dysfunction | Total | |

| Lymphatic leakage | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Normal central lymphatics (or sealed-off leak) | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Lymphatic obstruction or dysfunction | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| Total | 21 | 3 | 8 | 32 |

The data are number of patients.

DCMRL = dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography, CL = conventional intranodal lymphangiography.

Outcomes according to the radiologic interventional feasibility

In the subset of patients with technically successful DCMRL (n = 65), it was found that 31 patients presented with interventional feasible anatomy, while 16 patients did not have feasible anatomy. For 11 patients, radiologic intervention was deemed not recommended due to peripheral lymphatic leakage or lymphatic anomalies (Fig. 1). The rates of technical and clinical success were higher when the anatomy was amenable to intervention compared to when it was not (technical success: 77.3% [17/22] vs. 33.3% [3/9], respectively; clinical success, 90.3% [28/31] vs. 62.5% [10/16], respectively). Furthermore, DCMRL identified seven patients who did not require any intervention, and clinical success was achieved for all of these patients.

The long-term follow-up results did not significantly differ from the initial clinical success rate. After patients' first discharge, no recurrence of leakage was observed, and improvement of manifestations was noted in only one patient who initially failed to achieve clinical success. In detail, for patients who did not achieve clinical success after initial management in the feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention group (2/31), both had persistent clinical manifestations attributable to their underlying lymphatic anomalies. In the not feasible anatomy group (6/16), no spontaneous regression was noted, and 2 patients died due to their underlying malignancy. In the not applicable for intervention group (8/11), one patient experienced improvement of ascites due to the improvement of their lymphoma, but the remaining 7 patients had persistent manifestations associated with their underlying lymphatic anomalies.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the capability of DCMRL to ascertain lymphatic pathogenesis and provide anatomical details relevant to the feasibility of interventions for various lymphatic disorders. The technical success rate of DCMRL was notably high at 92.9% (65/70), particularly for nontraumatic lymphatic disorders (94.1% [16/17]) and traumatic chylothorax (92.9% [39/42]). The interventional success rate was higher for patients whose DCMRL scans indicated feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention relative to those without (77.3% vs. 33.3%). The clinical success rate was highest in cases of traumatic chylothorax (92.9% [39/42]), in contrast to the 23.5% (4/17) in patients with nontraumatic lymphatic disorders.

The high technical success of DCMRL (92.9% [65/70]) aligns with previous studies of 92.0% with transpedal contrast-enhanced MRL9 and 100.0% with noncontrast MRL.10 The clinical success rate for chylothorax assessed with transpedal contrast-enhanced MRL was 84% (21/25), slightly lower than our findings (92.9% [39/42]). Considering the pooled overall clinical success rate of 60.1% for lymphatic interventions addressing chylothorax from various causes,13 the clinical success rate of only traumatic chylothorax can be considered favorable. The technical success rate for lymphatic interventions specific to traumatic chylothorax (72.0% [18/25]) is marginally higher than the pooled rate for all chylothorax types (61.5%).13 The distinction of causes (traumatic vs. nontraumatic) seems to correlate with the technical and clinical outcomes, as evidenced by a meta-analysis indicating higher clinical success for traumatic over nontraumatic chylothorax.13 DCMRL was instrumental in determining the causes of lymphatic dysfunction in line with patients’ clinical histories and identifying cases where lymphatic leakage was sealed off, precluding the need for further intervention.

In patients with traumatic chylous ascites, technical failure occurred more frequently (27.3% [3/11]), and clinical success was evident in only 72.7% (8/11). Considering the high-resolution rates (71–100%) of chylous ascites following conservative management,14 the clinical success observed in our study was not remarkably high, with half of the patients requiring subsequent lymphatic interventions. However, DCMRL is primarily suitable for detecting leakage from central lymphatics, making it inadequate for identifying leakage from the complex mesenteric and hepatic lymphatics. Therefore, if no leakage from central lymphatics is detected but leakage from other lymphatic structures is still suspected, an interventional approach such as transhepatic lymphangiography or surgical approach as mesenteric lymphangiography would be needed to diagnosis.15 In other words, DCMRL has inherent limitations in diagnosing traumatic ascites, which requires evaluation of more complex lymphatic structures, compared to chylothorax, which is mainly due to thoracic duct injury.

In patients with nontraumatic lymphatic disorders, the clinical success rate was the lowest despite the highest rate of lymphatic interventions (64.7% [11/17]). The specific causes included primary lymphatic dysfunction due to lymphangioleiomyomatosis or central lymphatic flow disorders8 and secondary causes such as liver cirrhosis. Lymphatic fluid accumulation may result from obstruction due to myoproliferation in the perilymphatic space,16 reduction or agenesis of central lymphatics,8 or compromised lymphatic drainage.17 Traditional intervention strategies that obstruct central lymphatics may provide immediate relief from lymphatic fluid accumulation but fail to confer long-term clinical benefits. Consequently, initiating treatment for the underlying condition, such as mTOR inhibitors for lymphangioleiomyomatosis or liver transplantation for cirrhosis, is essential. Indiscriminate embolization within the central lymphatics, potentially worsening obstruction over time, must be approached with caution. DCMRL is valuable in distinguishing nontraumatic causes by providing dynamic insights into lymphatic function, specifically the absence of active contrast extravasation requiring embolization or repair.

Another important advantage of DCMRL is its ability to determine technical feasibility for interventions. As anticipated, interventional technical success was more common for patients with feasible anatomy for radiologic intervention than in those with unsuitable anatomy (77.3% vs. 33.3%); a parallel trend was observed in clinical outcomes. These findings suggest that the visualization of anatomical detail facilitated by DCMRL can inform and possibly predict the success of interventions. Moreover, by identifying scenarios where intervention is unnecessary or where leakage is sealed-off, DCMRL can prevent unwarranted additional lymphatic procedures. Though the comparison cannot be performed on all patients, the high concordance rate with CL (96.9%) supports the use of DCMRL as an accurate imaging method for supporting treatment decisions. Furthermore, comparing DCMRL with other lymphangiography modalities, such as CT,18 could help establish the characteristics of imaging techniques that can substitute for CL.

Despite the advantages of DCMRL in assessing the underlying anatomy for planning interventions in suspected lymphatic disorders, our study had limitations. The requirement for an additional procedure for ultrasonographic lymph node cannulation is a drawback of DCMRL. Alternative methods, such as transpedal MRL,9 which do not necessitate intranodal cannulation, are also in use. However, these alternatives require a longer observation time post-contrast injection (approximately 15 minutes) and are prone to venous contamination, which can obscure the evaluation of the lymphatic anatomy, particularly in complex cases. With the collaboration of proficient radiologists and technicians in the MR suite ensuring stable cannulation, DCMRL can deliver extensive anatomical and dynamic information about the lymphatic system. Furthermore, our single-center, retrospective cohort study may have had a selection bias. The rarity of lymphatic disorders and the often self-limiting nature of traumatic lymphatic leakage necessitate further multicenter studies to validate our findings to yield generalizable results.

In conclusion, DCMRL is instrumental in identifying the causes of lymphatic disorders, and the effectiveness of DCMRL, as well as the clinical outcomes for patients, vary based on the underlying causes. The insights provided by DCMRL are valuable for determining the necessary lymphatic interventions and predicting outcomes, thereby playing a critical role in the management of lymphatic disorders.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Shin JH.

- Data curation: Ahn Y, Koo HJ, Choe J, Chu HH, Yang DH, Kang JW.

- Formal analysis: Ahn Y, Koo HJ.

- Investigation: Ahn Y, Koo.

- Methodology: Ahn Y, Koo HJ.

- Validation: Ahn Y, Koo HJ, Choe J, Chu HH, Yang DH, Kang JW.

- Visualization: Ahn Y, Koo HJ, Choe J, Chu HH, Shin JH.

- Writing - original draft: Ahn Y, Koo HJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Ahn Y, Koo HJ, Shin JH.

References

- 1.Cholet C, Delalandre C, Monnier-Cholley L, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, El Mouhadi S, Arrivé L. Nontraumatic chylothorax: nonenhanced MR lymphography. Radiographics. 2020;40(6):1554–1573. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020200044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto T, Yamagami T, Kato T, Hirota T, Yoshimatsu R, Masunami T, et al. The effectiveness of lymphangiography as a treatment method for various chyle leakages. Br J Radiol. 2009;82(976):286–290. doi: 10.1259/bjr/64849421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath EE, Blades Z, Anderson PB. Chylothorax: aetiology, diagnosis and therapeutic options. Respir Med. 2010;104(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dori Y. Novel lymphatic imaging techniques. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19(4):255–261. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnamurthy R, Hernandez A, Kavuk S, Annam A, Pimpalwar S. Imaging the central conducting lymphatics: initial experience with dynamic MR lymphangiography. Radiology. 2015;274(3):871–878. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimpalwar S, Chinnadurai P, Chau A, Pereyra M, Ashton D, Masand P, et al. Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography: categorization of imaging findings and correlation with patient management. Eur J Radiol. 2018;101:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn Y, Koo HJ, Yoon HM, Choe J, Joo EY, Song MH, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography and lymphatic interventions for pediatric patients with various lymphatic diseases. Lymphat Res Biol. 2023;21(2):141–151. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2021.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savla JJ, Itkin M, Rossano JW, Dori Y. Post-operative chylothorax in patients with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(19):2410–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pieper CC, Feisst A, Schild HH. Contrast-enhanced interstitial transpedal MR lymphangiography for thoracic chylous effusions. Radiology. 2020;295(2):458–466. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyun D, Lee HY, Cho JH, Kim HK, Choi YS, Kim J, et al. Pragmatic role of noncontrast magnetic resonance lymphangiography in postoperative chylothorax or cervical chylous leakage as a diagnostic and preprocedural planning tool. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(4):2149–2157. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choe J, Koo HJ, Ahn Y, Lee GD, Yang DH, Kang JW, et al. Evaluation of chylothorax using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography after lung cancer surgery. Lymphat Res Biol. 2023;21(4):343–350. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2022.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hur S, Shin JH, Lee IJ, Min SK, Min SI, Ahn S, et al. Early experience in the management of postoperative lymphatic leakage using lipiodol lymphangiography and adjunctive glue embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(8):1177–1186.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim PH, Tsauo J, Shin JH. Lymphatic interventions for chylothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(2):194–202.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weniger M, D’Haese JG, Angele MK, Kleespies A, Werner J, Hartwig W. Treatment options for chylous ascites after major abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2016;211(1):206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hur S, Kim J, Ratnam L, Itkin M. Lymphatic intervention, the frontline of modern lymphatic medicine: part II. Classification and treatment of the lymphatic disorders. Korean J Radiol. 2023;24(2):109–132. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2022.0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu JH, Doerr CH, Fisher SD, Olson EJ, Sahn SA. Chylothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 2003;123(2):623–627. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung C, Iwakiri Y. The lymphatic vascular system in liver diseases: its role in ascites formation. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19(2):99–104. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel S, Hur S, Khaddash T, Simpson S, Itkin M. Intranodal CT lymphangiography with water-soluble iodinated contrast medium for imaging of the central lymphatic system. Radiology. 2022;302(1):228–233. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]