Abstract

Aims

The CASTLE‐HTx trial showed the benefit of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation compared to medical therapy in decreasing mortality, need for left ventricular assist device implantation or heart transplantation (HTx) in patients with end‐stage heart failure (HF). Herein we describe the effects of catheter ablation on AF burden, arrhythmia recurrences, and ventricular function in end‐stage HF.

Methods and results

The CASTLE‐HTx protocol randomized 194 patients in end‐stage HF with AF to catheter ablation and medical therapy or medical therapy alone. AF burden, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and type of AF were assessed at baseline and at each follow‐up visit. Overall, 97 patients received ablation; 66 patients (68%) underwent pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) and 31 patients (32%) were treated with PVI and additional ablation. Electroanatomic mapping showed the extent of left atrial low voltage (cardiomyopathy) >10% in 31 (31.9%) patients. At 12 months post‐ablation, persistent AF was present in 31/89 patients (34.8%), which was significantly less frequent compared to baseline (p = 0.0001). Median AF burden reduction was 36.3 (interquartile range 13.6–63.3) percentage points at 12 months and LVEF improved from 29.2 ± 6.2% to 39.1 ± 8.3% (p < 0.001) following ablation. AF burden reduction <50% was significantly associated with LVEF improvement ≥5% at 12 months after ablation (p = 0.017).

Conclusion

Atrial fibrillation ablation in end‐stage HF leads to a substantial decrease in AF burden, a regression from persistent to paroxysmal AF and notably improved LVEF. Favourable ablation outcomes were observed in patients regardless of the presence or absence of signs indicating left atrial cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Heart failure, Catheter ablation, Heart transplantation, Left ventricular assist device

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). 1 AF leads to decreased cardiac output, absence of atrial contraction, and irregular ventricular filling, which are harmful effects contributing to the development of progressive HF. Increasing evidence indicates that rhythm control is superior to rate control in patients with HF and AF 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 and clinical trials have demonstrated that AF ablation decreases mortality and/or hospitalizations in these patients. 3 , 4 , 5 This has resulted in an expanded acceptance for catheter ablation as the primary treatment in the latest guidelines on AF management. 6 CASTLE‐HTx examined the impact of catheter ablation on symptomatic AF in patients with end‐stage HF referred for heart transplantation (HTx) evaluation. 7 Catheter ablation led to a reduction in a combined endpoint of all‐cause mortality, left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation, and urgent HTx when compared to medical therapy alone. The aim of this CASTLE‐HTx subanalysis was to examine the impact of ablation treatment on arrhythmia burden, AF regression from persistent to paroxysmal disease states or even sinus rhythm and left ventricular function in patients with end‐stage HF.

Methods

Trial design and study population

CASTLE‐HTx was a single‐centre, open‐label, investigator‐initiated, superiority, randomized clinical trial conducted at the Herz‐ und Diabeteszentrum Nordrhein‐Westfalen (Bad Oeynhausen, Germany). The detailed design of the trial has been published previously. 8 The study randomly assigned patients with AF and end‐stage HF who had been referred for HTx evaluation to either catheter ablation and guideline‐directed medical therapy (GDMT) or medical therapy alone. The primary endpoint of the trial was a composite of death from any cause, implantation of a LVAD, or urgent HTx. All patients had an implantable cardiac device with activated arrhythmia detection allowing for continuous rhythm monitoring. In this post hoc analysis, we included all patients enrolled into CASTLE‐HTx who underwent catheter ablation for AF regardless of initial randomization allocation. Data for patients not receiving ablation was obtained and adjusted from 7 to determine the ablation‐effect on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and AF burden. The Graphical Abstract shows a summary of the study design. Endpoints included improvement of LVEF and AF burden at 12 months after randomization compared to baseline values, as well as type of AF at 12 months after ablation. Furthermore, ablation effects were analysed in relation to presence of left atrial (LA) low voltage areas suggestive for atrial cardiomyopathy. The study was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of this report to the trial protocol. The trial was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from the Else‐Kröner‐Fresenius‐Stiftung.

Pre‐procedural management

Left atrial thrombus formation was ruled out before ablation by transesophageal echocardiography. Patients taking vitamin K antagonists were given continuous anticoagulation therapy with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0–3.0. Patients taking direct oral anticoagulants stopped the medication for one half‐life before the ablation procedure and resumed it within 4 h after checking for pericardial effusion.

Catheter ablation for pulmonary vein isolation

The procedures were performed under deep sedation with continuous propofol infusion and fractionated midazolam and fentanyl injection. Heparin was given to achieve systemic anticoagulation with a targeted active clotting time exceeding 300 s. Transseptal puncture was performed under fluoroscopic guidance using a modified Brockenbrough technique with 8.5 F transseptal sheaths and a puncture needle (BRK‐1 needle, St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA). All procedures were conducted using an electroanatomic mapping system (CARTO 3 V7, Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA, USA or Ensite, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). Electroanatomic mapping was performed in all patients in sinus rhythm using multipolar mapping catheters (Lasso Nav, Biosense Webster; Pentaray, Biosense Webster; Advisor FL, Abbott; Advisor HD‐Grid, Abbott) in order to identify areas of structural remodelling in the atrial histoarchitecture representing cardiomyopathy. 9 Ablation was considered successful if all pulmonary veins (PV) were isolated and sinus rhythm was restored, if not already present. PV isolation (PVI) was confirmed by demonstration of entry and exit block. Ablation was performed with contact force enabled catheters in all patients (ThermoCool Smarttouch Surroundflow, Biosense Webster or TactiCath, Abbott).

Additional ablation lesions

The presence of atrial cardiomyopathy was defined as regions with bipolar voltage below 0.5 mV when mapping in sinus rhythm. 10 Low voltage areas were quantified as a percentage of the LA surface using the 3D mapping system and classified into two categories: (i) <10% (mild extent of atrial cardiomyopathy), and (ii) >10% (relevant extent of atrial cardiomyopathy). Patients with relevant LA cardiomyopathy underwent PVI and additional ablation targeting the identified arrhythmia substrate. Ablation was performed by creating anterior/septal lines connecting the anterior mitral‐valve annulus with the left superior or right superior PV. LA posterior wall isolation (PWI) was conducted in patients with posterior wall substrates. PWI was achieved by ablation of a roof line and a linear lesion connecting the right inferior PV with the left inferior PV resulting in a posterior box lesion. Patients with confirmed cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI)‐dependent atrial flutter underwent ablation of the CTI. Focal atrial arrhythmias were treated with localized focal ablation.

Post‐procedural care and clinical follow‐up

Transthoracic echocardiography was conducted right after the procedure and the following day to exclude pericardial effusion. A figure‐of‐eight suture was used to close femoral access sites. All patients were relocated to a recovery area. After a 2–4‐h observation period, patients were moved to the general ward. All patients received proton pump inhibitors for 4 weeks after catheter ablation. Antiarrhythmic medication for AF was discontinued after ablation and could be reinitiated in case of an arrhythmia recurrence at the discretion of the treating physician. Patient follow‐up appointments were scheduled every 3 months during the first year and then yearly thereafter. During the follow‐up visits, patients underwent echocardiography, had their implanted devices interrogated, were interviewed by their physician about HF and arrhythmia symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiography for estimation of LVEF was performed as to institutional standards in accordance to the current guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography (2D biplane method of disks). 11 Any adverse events were recorded. Calculation of the AF burden was performed as reported previously. 8 In brief, the accuracy of the device interrogations was reviewed and verified and the cumulative duration of all atrial arrhythmia episodes expressed as a percentage of total time in the 3 months preceding the visit was used to calculate AF burden.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were presented using mean ± standard deviation or median according to the distribution. For categorical variables, number and percentages were presented. Group comparisons for continuous variables, were analysed using Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon tests. For dichotomous qualitative variables, chi‐squared tests were performed to assess group differences. Sankey diagrams were used for graphical representation of quantity flows. The primary and secondary outcome analysis was conducted according to the individual ablation approach. We evaluated changes for LVEF and AF burden at 12 months by calculating the difference relative to baseline. A multivariate analysis was performed to analyse the association of clinical parameter with LVEF improvement 12 months after ablation utilizing a model of logistic regression. Using t‐tests for independent samples, we determined 95% confidence intervals (CI) for between‐group differences in mean change. Analyses were conducted with the use of SPSS Statistics software, version 29 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient population and baseline characteristics

The CASTLE‐HTx trial randomized 97 patients to the catheter ablation and 97 patients to the medical‐therapy group. AF ablation was performed in 97 patients, with 81 patients (84%) in the ablation group and 16 patients (16%) initially randomized to medical therapy. Paroxysmal AF was present in 25 patients (26%), while persistent AF was observed in 72 patients (74%). Mean patient age was 62 ± 11 years and mean LVEF 29 ± 6%. Sixty‐four (66%) patients had a New York Heart Association functional class of III or IV. The average LA diameter was 48 ± 6 mm. The median N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide was 3065 (interquartile range 1008–3970) pg/ml. Additional characteristics of patients are provided in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients at baseline according to the treatment they received a

| Characteristic | Ablation received (n = 97) | No ablation received (n = 97) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62 ± 11 | 65 ± 11 | 0.050 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 86 (89) | 71 (73) | 0.006 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28 ± 4 | 27 ± 5 | 0.074 |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | 0.378 | ||

| II | 33 (34) | 28 (29) | |

| III | 52 (54) | 54 (56) | |

| IV | 12 (12) | 15 (15) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 29 ± 6 | 25 ± 6 | 0.054 |

| Type of atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 0.275 | ||

| Paroxysmal | 25 (26) | 34 (35) | 0.160 |

| Persistent | 59 (61) | 49 (51) | 0.148 |

| Long‐standing persistent (duration of >1 year) | 13 (13) | 14 (14) | 0.836 |

| Atrial fibrillation burden, % | 51 ± 31 | 48 ± 35 | 0.486 |

| Burden <50, n (%) | 49 (51) | 55 (57) | 0.388 |

| Burden ≥50, n (%) | 48 (49) | 42 (43) | |

| Heart rate, bpm | 80 ± 21 | 82 ± 21 | 0.648 |

| Heart failure aetiology, n (%) | 0.556 | ||

| Ischaemic | 36 (37) | 40 (41) | |

| Non‐ischaemic | 61 (63) | 57 (59) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 78 (80) | 72 (74) | 0.304 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 48 ± 6 | 48 ± 8 | 0.873 |

| COPD, n (%) | 9 (9) | 3 (3) | 0.074 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25 (26) | 31 (32) | 0.342 |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 0.054 |

| Implantable cardiac device, n (%) | 0.203 | ||

| ICD | 61 (63) | 48 (49) | |

| CRT‐D | 32 (33) | 41 (42) | |

| Rhythm monitor | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | |

| Pacemaker | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/ml, median [IQR] | 3065 [1008–3970] | 3501 [1243–7240] | 0.061 |

| 6‐min walk test distance, m | 304 ± 71 | 305 ± 65 | 0.927 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 62 ± 23 | 56 ± 28 | 0.098 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 15 ± 2 | 13 ± 3 | <0.001 |

| Medication, n (%) | |||

| Amiodarone | 44 (45) | 46 (47) | 0.773 |

| Beta‐blocker | 95 (98) | 89 (92) | 0.051 |

| Diuretics | 68 (70) | 79 (81) | 0.065 |

| ACE‐inhibitor or ARB | 32 (33) | 39 (40) | 0.297 |

| MRA | 48 (49) | 50 (52) | 0.774 |

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 65 (67) | 58 (60) | 0.297 |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 23 (24) | 24 (25) | 0.867 |

Plus–minus values are mean ± standard deviation.

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT‐D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2.

Baseline evaluation was performed before randomization. CASTLE‐HTx risk score was calculated by left ventricular ejection fraction <30% (2 points), atrial fibrillation burden ≥50% (1 point) and NYHA class ≥3 (2 points).

Procedural data

All procedures were conducted under conscious sedation without need for general anaesthesia. The average time from femoral sheath insertion to removal was 96 ± 25 min, with a mean LA dwelling time of 54 ± 31 min. The mean ablation time was 1589 ± 811 s. The average LA volume was 182 ± 51 ml. The majority of patients (68%) had <10% of LA bipolar low voltage areas (no/mild extend of LA cardiomyopathy). In these patients PVI was performed without subsequent ablation lesions. PVI and additional lesions in the left atrium were conducted in 31 (32%) patients: anterior or septal linear ablation was performed in 24 patients (24.7%), ablation of roof lines in 11 patients (11.3%) and PWI in 5 patients (5.2%). Acute bidirectional block along linear lesions and PWI was achieved in all patients receiving these ablation lesions. Four minor periprocedural complications occurred, all of which were associated with the vascular access site and could be managed without intervention. Additional procedural information is provided in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Procedural characteristics

| Randomized, n | 194 |

| Ablation performed, n | 97 |

| Time of procedure since baseline, days | 36 ± 60 |

| Skin‐to‐skin time, min | 96 ± 25 |

| Left atrium time, min | 54 ± 31 |

| Area dose product, [cGy]*cm2 | 469 ± 728 |

| Radiation time, min | 6 ± 3 |

| Ablation time, s | 1589 ± 811 |

| Left atrial volume, ml | 182 ± 51 |

| Radiofrequency applications, n | 55 ± 27 |

| Amount of left atrial bipolar low voltage, n (%) | |

| <10% (mild extend of atrial cardiomyopathy) | 66 (68.0) |

| >10% (relevant extend of atrial cardiomyopathy) | 31 (32.0) |

| Pulmonary vein isolation alone, n (%) | 66 (68.0) |

| Pulmonary vein isolation and ablation of additional lesions, n (%) | 31 (32.0) |

| Types of additional lesions, n (%) | |

| Anterior line | 16 (16.5) |

| Septal line | 8 (8.2) |

| Roof line | 11 (11.3) |

| Box lesion | 5 (5.2) |

| Right atrial ablation (including cavotricuspid isthmus ablation and focal ablation) | 16 (16.5) |

| Sedation and analgesia, n (%) | |

| Conscious sedation | 97 (100) |

| General anaesthesia | – |

| Procedure‐related complications, n (%) a | |

| Any complication | 4 (4.1) |

| Major, requiring intervention | – |

| Minor, not requiring intervention | 4 (4.1) |

| Groin haematoma | 3 |

| False aneurysm | 1 |

Plus–minus values are meas ± standard deviation.

Complications which occurred after catheter ablation during hospitalization.

Atrial fibrillation burden and left ventricular ejection fraction

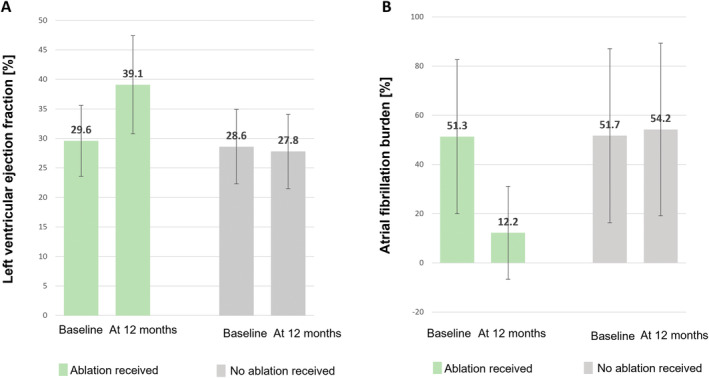

The baseline AF burden in patients receiving ablation was 51.4 ± 31.3%. A mean burden reduction of 39.1 ± 31.8 percentage points (median: 36.3, interquartile range 13.62–63.25 percentage points) to an absolute AF burden of 12.2 ± 18.9% was observed at 12 months after randomization irrespective of the ablation strategy. Compared to baseline values, a statistically significant lower AF burden was observed at 12 months after randomization (p < 0.001). The average LVEF improved by 9.5 ± 7.7 percentage points (relative change in LVEF 32.4 ± 26.0%) to a mean LVEF of 39.2% which was a statistically significant increase at 12 months after randomization compared to baseline. Patients with low‐grade LA cardiomyopathy who underwent PVI showed similar reductions in AF burden and improvements in LVEF compared to patients with higher degree of LA cardiomyopathy who had additional individualized ablation and PVI. Details on AF burden reduction and LVEF improvement according to the ablation strategy are provided in Table 3 . Baseline and follow‐up data for AF burden and LVEF in patients not receiving ablation compared to patients receiving ablation is shown in Figure 1 . More data are provided in online supplementary Figure S1 .

Table 3.

Impact of catheter ablation and ablation strategy on left ventricular function and atrial fibrillation burden

| Ablation received | PVI alone | PVI and additional lesion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | |||

| At baseline | |||

| No. of patients evaluated | 97 | 66 | 31 |

| Value, % |

29.2 ± 6.2 |

28.8 ± 6.5 |

30.1 ± 5.7 |

| At 12 months after randomization | |||

| No. of patients evaluated | 91 | 62 | 29 |

| Baseline value, % |

29.6 ± 6.0 |

29.0 ± 6.3 |

30.7 ± 5.3 |

| Value at 12 months, % |

39.1 ± 8.3 |

39.2 ± 9.2 |

38.8 ± 6.0 |

| Improvement — percentage points |

9.5 ± 7.7 |

10.2 ± 8.4 |

8.1 ± 6.0 |

| Atrial fibrillation burden, % | |||

| At baseline | |||

| No. of patients evaluated | 97 | 66 | 31 |

| Value, % |

51.4 ± 31.3 |

49.5 ± 30.5 |

55.4 ± 6.0 |

| At 12 months after randomization | |||

| No. of patients evaluated | 90 | 61 | 29 |

| Baseline value, % |

51.3 ± 31.3 |

48.6 ± 30.2 |

56.9 ± 33.5 |

| Value at 12 months, % |

12.2 ± 18.9 |

11.9 ± 18.9 |

12.8 ± 19.3 |

| Reduction, percentage points |

39.1 ± 31.8 |

36.7 ± 29.0 |

44.1 ± 37.2 |

PVI, pulmonary vein isolation.

Patients who received catheter ablation and survived 12 months since randomization without a primary endpoint event (composite of death from any cause, left ventricular assist device implantation or heart transplantation) were analysed.

Figure 1.

Improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction (A) and atrial fibrillation burden (B) for patients treated with ablation and not treated with ablation. The data from patients who did not receive ablation were obtained and adjusted from. 7 I bars indicate the standard deviation.

Arrhythmia recurrence and atrial fibrillation regression

At 12 months after ablation, 58 patients (65.2%) with recurrent AF had paroxysmal or no AF recurrence while 31 patients (34.8%) had persistent AF (Table 4 ). Arrhythmia regression for all patients undergoing ablation is shown in Figure 2 . At 12 months post‐ablation a significant reduction of persistent AF was observed in patients undergoing ablation irrespective of the ablation strategy (p = 0.0001). The effect was equally observed in patients who received PVI alone (p = 0.0001) and in patients undergoing PVI and additional ablation (p = 0.04).

Table 4.

Type of atrial fibrillation at 12 months after catheter ablation

| Ablation received (n = 97) | PVI alone (n = 66) | PVI and additional lesion (n = 31) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Persistent | 72 (74.2) | 51 (77.3) | 21 (67.7) |

| Paroxysmal | 25 (25.8) | 15 (22.7) | 10 (32.3) |

| 12 months | |||

| With primary endpoint event | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| Patients evaluated | 89 | 60 | 29 |

| Persistent | 31 (32.0) | 19 (28.8) | 12 (38.7) |

| Paroxysmal | 52 (53.6) | 36 (54.5) | 16 (51.6) |

| Sinus rhythm (no atrial fibrillation) | 6 (6.2) | 5 (7.6) | 1 (3.2) |

PVI, pulmonary vein isolation.

Patients who received catheter ablation and survived 12 months following ablation without a primary endpoint event (composite of death from any cause, left ventricular assist device implantation or heart transplantation) were analysed.

Figure 2.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) regression from persistent to paroxysmal AF or sinus rhythm (SR). The type of AF before and after catheter ablation irrespective of the ablation strategy is shown at 12 months after ablation. Patients who received catheter ablation and survived 12 months following ablation without a primary endpoint event (composite of death from any cause, left ventricular assist device implantation or heart transplantation) were analysed.

Multivariate analysis

Logistic regression models revealed AF burden reduction to <50% as the only significant factor associated with an LVEF improvement of ≥5% at 12 months after ablation (p = 0.017, odds ratio 14.25, 95% CI 1.6–127.12) (Table 5 ). In addition, there was a trend towards a positive association of male sex with LVEF improvement ≥5% at 12 months after ablation, too (p = 0.064, odds ratio 5.43, 95% CI 0.9–32.59).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis

| Coefficient β | Standard error | z | p‐value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.667 | 1.01 | 0.96–1.07 |

| Male sex | 1.69 | 0.91 | 1.85 | 0.064 | 5.43 | 0.9–32.59 |

| NYHA class III at baseline | 0.14 | 0.84 | 0.17 | 0.865 | 1.15 | 0.22–5.96 |

| NYHA class IV at baseline | −0.63 | 1.32 | 0.48 | 0.634 | 0.53 | 0.04–7.08 |

| LA fibrosis >10% | −1.17 | 0.75 | 1.56 | 0.119 | 0.31 | 0.07–1.35 |

| AF burden at 12 months <50% | 2.66 | 1.12 | 2.38 | 0.017 | 14.25 | 1.6–127.12 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CI confidence interval; LA, left atrial; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Discussion

Major findings

This post hoc analysis of the CASTLE‐HTx trial has four major findings. First, a significant reduction of AF burden was achieved after ablation. Second, a regression from persistent to paroxysmal AF related to ablation was observed in a relevant number of patients. Third, patients showed a significant improvement in LVEF during follow‐up. Moreover, the favourable results of catheter ablation appeared comparable for patients in end‐stage HF irrespective of their individual extent of LA cardiomyopathy. Fourth, AF burden reduction to <50% was significantly associated with LVEF improvement of ≥5% at 12 months after ablation.

Atrial fibrillation recurrence and burden reduction

A subanalysis of CASTLE‐AF demonstrated that a single event of recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmia lasting more than 30 s after ablation did not lead to decreased survival or reduced hospitalizations for HF while elevated AF burden rates 6 months after ablation were indicative for such events. 12 This finding was recently supported in an experimental model using human‐induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes that were electrically stimulated to mimic AF. 13 A burden of irregular electrical stimulation exceeding 60% of the time was associated with cellular alterations that are present in patients with HF. 13 A subanalysis of the CABANA trial reported 37% lower AF recurrence rates among HF patients who underwent AF ablation. 14 An analysis within the EAST‐AFNET trial revealed decreased occurrences of clinical outcomes such as death or hospitalization for HF and improvement in LVEF in HF patients with preserved and reduced LVEF. 15 Notably, we observed a substantial reduction in AF burden in patients undergoing catheter ablation; this reduction was mainly driven by AF regression. The baseline AF burden rates in our cohort were comparable to those documented in the CASTLE‐AF trial and in both trials the reduction in burden was comparable. 5 Our data are consistent with previous findings and support for including AF burden assessment in the reporting standards for evaluating AF ablation success, particularly in patients with HF.

The recent ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of AF suggests a class 1A indication for catheter ablation of AF in suitable patients with AF and HFrEF who are on GDMT and who have a reasonable expectation of procedural benefit. 6 However, a clear statement outlining the prioritized goals or clinical endpoints of AF ablation in HF is missing. In this context, our data support the idea that the primary goal of catheter ablation in HF patients should be achieving a significant reduction in AF burden rather than focusing on factors such as the ‘30‐s rule’ of AF recurrence. 10

Atrial fibrillation regression and improvement of left ventricular function

Atrial fibrillation frequently advances from paroxysmal to persistent types, a transition that has been linked to an elevated likelihood of clinical adverse events. 16 Catheter ablation has been associated with a decrease from persistent to paroxysmal AF. 17 , 18 Until to date there are no data on the effects of AF regression on hard clinical endpoints. In patients with persistent AF, the substantial reduction in AF burden may have been primarily attributable to AF regression. Consequently, AF regression by ablation may be an adequate therapeutic approach for patients with HF as only ablation but not medical therapy resulted in LVEF recovery in the CASTLE trials. 5 , 7 Previous studies found beneficial effects of AF ablation on LVEF in patients with HFrEF. For instance, The ATAAC trial reported a change in LVEF from 8.1 ± 4% 4 and the CAMERA‐MRI study reported an increase of LVEF of 18 ± 13% after catheter ablation. 3 In the CASTLE‐AF trial, 57% of patients in the ablation group experienced an increase in LVEF of at least 5%. 5 This improvement was observed in patients with severely impaired LVEF (<20%) as well as in those with less severe HF. 5 Our results validate the outcomes in terms of LVEF improvement reported in CASTLE‐AF and demonstrate their potential applicability to patients in end‐stage HF. We found that AF burden reduction to <50% was significantly associated with and LVEF improvement of ≥5% at 12 months after ablation. Longer periods of sinus rhythm likely enhance cardiac output, LVEF, exercise tolerance, and quality of life. 5 , 7 , 12 Our data indicate that AF ablation is crucial in patients with end‐stage HF leading to improved hard clinical outcomes as well as AF regression, improved left ventricular function, and decreased AF burden. These factors are considered to have a substantial influence on patients in end‐stage HF. However, the listing process should not be delayed for prioritized HTx candidates due to the scarcity of available donor organs.

The impact of left atrial fibrosis on the outcomes of catheter ablation in end‐stage heart failure

Left atrial cardiomyopathy is a validated predictor of failure in AF ablation. 19 The majority of patients in CASTLE‐HTx had only a lower grade of LA cardiomyopathy based on bipolar voltage mapping. The finding is remarkable considering the advanced stage of HF in the patients under investigation. Our findings suggest that the presence of advanced HF is not a reliable indicator of advanced atrial cardiomyopathy. Patients with evidence for LA cardiomyopathy regularly received individual substrate modification by additional ablation beyond PVI. This concept was previously evaluated in patients without HF who presented with AF, and it demonstrated encouraging outcomes. 9 , 20 In the CASTLE‐HTx trial, patients with and without LA cardiomyopathy had a comparable decrease in AF burden. However, early catheter ablation before the first signs of LA fibrosis and cardiomyopathy is a plausible approach to prevent structural alterations and that may improve the effectiveness of rhythm control especially in patients with HFrEF.

Limitations

This exploratory post hoc analysis was limited to generating hypotheses. As a result of the as‐treated design, some patients who underwent ablation were randomized into the medical therapy group, potentially introducing bias into the analysis. The utilization of different mapping catheters featuring varying interelectrode spacings might have contributed to variations in voltage mapping. Notably, low voltage areas as assessed in 3D mapping are not the only indicators of atrial cardiomyopathy. Other factors may also contribute to an atrial cardiomyopathy that cannot be visualized with this method. Furthermore, the relatively low complication rate observed in this cohort might be related to the fact that all patients were suitable for evaluation of cardiac transplant, potentially leading to exclusion of patients with a higher comorbidity load. A major strength of this study is the evaluation of AF burden by continuous monitoring in all patients. However, it is still possible that the devices and their associated algorithms may have been unable to accurately identify and classify certain arrhythmia episodes. At last, echocardiography was performed as to institution standards in the absence of an echocardiographic core lab.

Conclusions

Atrial fibrillation ablation in end‐stage HF leads to a substantial decrease in arrhythmia burden, a regression from persistent to paroxysmal AF stages and notable improvements in LVEF. These ablation effects were observed in patients with and without advanced LA cardiomyopathy to the same degree.

Funding

The trial was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from the Else‐Kröner‐Fresenius‐Stiftung. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest: C.S. received research support and lecture fees from Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Biosense Webster; is a consultant for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Biosense Webster; has received grant support from the Else Kröner‐Fresenius‐Stiftung and Deutsche Herzstiftung. H.J.G.M.C. reports support from The Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative: an initiative with support of the Dutch Heart Foundation, CVON 2014–9: reappraisal of atrial fibrillation: interaction between hypercoagulability, electrical remodelling, and vascular destabilization in the progression of AF (RACE V), outside this work. N.F.M. has received grant support and consulting fees from Abbott, Wavelet Health, Medtronic, Vytronus, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, GE Health Care, and Siemens; has received consulting fees from Preventice; and holds equity in Marrek and Cardiac Design. S.S. received speaker fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. V.R. has received grant support from Abbott Vascular and Edwards Lifesciences. P.S. is member of the Advisory Board for Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific und Medtronic. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.

Acknowledgement

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

- 1. Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, Magnani JW, McManus DD, Lubitz SA, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets heart failure and vice versa: Temporal associations and differences in preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 2016;133:484–492. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khan MN, Jaïs P, Cummings J, Di Biase L, Sanders P, Martin DO, et al.; PABA‐CHF Investigators . Pulmonary‐vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1778–1785. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prabhu S, Taylor AJ, Costello BT, Kaye DM, McLellan AJA, Voskoboinik A, et al. Catheter ablation versus medical rate control in atrial fibrillation and systolic dysfunction: The CAMERA‐MRI study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1949–1961. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Di Biase L, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, Santangeli P, Trivedi C, Lakkireddy D, et al. Ablation versus amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with congestive heart failure and an implanted device: Results from the AATAC multicenter randomized trial. Circulation 2016;133:1637–1644. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, Siebels J, Boersma L, Jordaens L, et al.; CASTLE‐AF Investigators . Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018;378:417–427. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;83:109–279. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sohns C, Fox H, Marrouche NF, Crijns HJ, Costard‐Jaeckle A, Bergau L, et al.; CASTLE HTx Investigators . Catheter ablation in end‐stage heart failure with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1380–1389. 10.1056/NEJMoa2306037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sohns C, Marrouche NF, Costard‐Jäckle A, Sossalla S, Bergau L, Schramm R, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in patients with end‐stage heart failure and eligibility for heart transplantation. ESC Heart Fail 2021;8:1666–1674. 10.1002/ehf2.13150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huo Y, Gaspar T, Schönbauer R, Wójcik M, Fiedler L, Roithinger FX, et al. Low‐voltage myocardium‐guided ablation trial of persistent atrial fibrillation. NEJM Evid 2022;1:EVIDoa2200141. 10.1056/EVIDoa2200141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2018;20:e1–e160. 10.1093/europace/eux274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitchell C, Rahko PS, Blauwet LA, Canaday B, Finstuen JA, Foster MC, et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic examination in adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2019;32:1–64. 10.1016/j.echo.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brachmann J, Sohns C, Andresen D, Siebels J, Sehner S, Boersma L, et al. Atrial fibrillation burden and clinical outcomes in heart failure: The CASTLE‐AF trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:594–603. 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Körtl T, Stehle T, Riedl D, Trausel J, Rebs S, Pabel S, et al. Atrial fibrillation burden specifically determines human ventricular cellular remodeling. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022;8:1357–1366. 10.1016/j.jacep.2022.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Packer DL, Piccini JP, Monahan KH, Al‐Khalidi HR, Silverstein AP, Noseworthy PA, et al. Ablation versus drug therapy for atrial fibrillation in heart failure: Results from the CABANA trial. Circulation 2021;143:1377–1390. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rillig A, Magnussen C, Ozga AK, Suling A, Brandes A, Breithardt G, et al. Early rhythm control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Circulation 2021;144:845–858. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PA, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:2920–2925. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tilz RR, Rillig A, Thum AM, Arya A, Wohlmuth P, Metzner A, et al. Catheter ablation of long‐standing persistent atrial fibrillation: 5‐year outcomes of the Hamburg Sequential Ablation Strategy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1921–1929. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wynn GJ, El‐Kadri M, Haq I, Das M, Modi S, Snowdon R, et al. Long‐term outcomes after ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation: An observational study over 6 years. Open Heart 2016;3:e000394. 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marrouche NF, Wilber D, Hindricks G, Jais P, Akoum N, Marchlinski F, et al. Association of atrial tissue fibrosis identified by delayed enhancement MRI and atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: The DECAAF study. JAMA 2014;311:498–506. 10.1001/jama.2014.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kircher S, Arya A, Altmann D, Rolf S, Bollmann A, Sommer P, et al. Individually tailored vs. standardized substrate modification during radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: A randomized study. Europace 2018;20:1766–1775. 10.1093/europace/eux310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.