Abstract

DNA transfer is ubiquitous in the human gut microbiota, especially among species of the order Bacteroidales. In silico analyses have revealed hundreds of mobile genetic elements shared between these species, yet little is known about the phenotypes they encode, their effects on fitness, or pleiotropic consequences for the recipient’s genome. In this work, we show that acquisition of a ubiquitous integrative conjugative element (ICE) encoding a Type VI secretion system (T6SS) shuts down the native T6SS of B. fragilis. Despite inactivating this T6SS, ICE acquisition increases the fitness of the B. fragilis transconjugant over its progenitor by arming it with the new T6SS. DNA transfer causes the strain to change allegiances so that it no longer targets ecosystem members with the same element yet is armed for communal defense.

Main Text:

Bacteroidales is an order of bacteria that includes numerous species that colonize the human gut at high density (1, 2), many likely persisting for decades (3). Two distinct types of contact-dependent interactions are pervasive among gut Bacteroidales; conjugal DNA transfer, and antagonism mediated by Type VI secretion systems (T6SS). T6SSs are contractile nanomachines where a pointed tube loaded with toxin effectors is injected into neighboring cells. Of the numerous species of this order, Bacteroides fragilis is one of the most antagonistic, producing several diffusible anti-bacterial toxins that thwart intra-species competitors (4–7), as well as a broadly targeting T6SS, which is produced only by this species (8).

The B. fragilis specific T6SS, known as genetic architecture 3 (GA3), is present in ~ 75% of strains analyzed (9) and robustly antagonizes diverse Bacteroidales species in vitro and in vivo (10–12). Two other T6SS loci are present in gut Bacteroidales, GA1 and GA2, which are each present on large integrative and conjugative elements (ICE) that readily transfer between Bacteroidales species in the human gut (8, 9). Of the numerous mobile genetic elements (MGE) of the gut Bacteroidales (9, 13), the GA1 and GA2 ICE are among the most transferred MGE with a conserved architecture that are currently spreading to multiple species within individuals of industrialized populations (9). Strong antagonism (1- to 3- log killing) has not been demonstrated for either the GA1 or GA2 T6SSs despite the presence of genes encoding potent toxins in these loci (8, 14, 15). There are few transcriptomic or phenotypic studies analyzing the fate of Bacteroidales MGEs once transferred to a new bacterial host (16, 17), and their impact on the recipient’s genome, transcriptome and proteome are not well understood (18)

Results

Prior analyses revealed that the B. fragilis GA3 T6SS fires constitutively in vitro (10) and without apparent directionality (19). We began by determining if constitutive in vitro firing is a general property of B. fragilis GA3 T6SSs. Firing in broth grown cultures is measured by the amount of the tube protein Hcp in the culture supernatant. We assayed for the presence of the main structural HcpGA3 in cells and culture supernatants of B. fragilis strains with distinct effector and immunity genes in the two GA3 T6SS locus variable regions (Fig. 1A). Stark differences were observed in the amount of Hcp in supernatants (Fig. 1B); most notable were strains 1284 and S36_L11, which synthesize but do not fire the T6SS under these in vitro conditions, and strain 2_1_56FAA, which does not synthesize HcpGA3. The ~25 kb GA3 T6SS loci of these three strains are very similar to those of strains that constitutively fire (fig. S1), some with only a few nucleotide variations, suggesting that factor or factors encoded outside the GA3 locus abrogates firing in these strains. Approximately18% of B. fragilis strains contain both GA3 and GA1 T6SS loci (9). Genomic analysis of the B. fragilis strains showed that five have a GA1 T6SS ICE in their genomes (fig. S2), including all three that do not fire the GA3 T6SS. These data suggest that a product of the GA1 ICE may inhibit firing of the GA3 T6SS. HcpGA3 protein synthesis is lacking in strain 2_1_56FAA, despite no obvious defects in its T6SS locus, hence we performed a transcriptomic analysis and found that the GA3 T6SS locus is not transcribed in strain 2_1_56FAA (data S1). This is the only strain of the set that contains two GA1 ICE in its genome, further supporting that the GA1 ICE affects the GA3 T6SS.

Fig. 1.

Acquisition of a GA1 ICE shuts down firing of the B. fragilis GA3 T6SS and its ability to antagonize. (A) Gene maps of the GA3 T6SS loci of 13 B. fragilis strains. Genes are color coded as shown below. Strain names are colored the same if they have the same variable region 1 and 2 (V1, V2), which contain genes encoding effector and immunity proteins. These 13 strains contained 3 different V1 (1A-1C) and five different V2 regions (2D-2H). (B) Western immunoblot analysis of the presence of the GA3 T6SS needle protein in the cell fraction or the supernatant. The same color coding used in panel A is used for these strains. Strains designated with an * have a GA1 T6SS ICE in their genomes. (C) Transfer frequencies of the GA1 ICE from donor strain B. finegoldii CL09T03C10 to either B. fragilis 638R or 638RΔT6, deleted for genes necessary for firing the GA3 T6SS. The B. fragilis strains have the ermG gene inserted at a null site and the B. finegoldii GA1 ICE contains the tetQ gene inserted at a null site to allow for selection of transconjugants. Five different ratios of donor:recipient were assayed for transfer frequency (fig. S3). (D) Western immunoblot analysis of the cellular fraction and supernatants of 638R and 638R-GA1 transconjugants 5 and 6. BSAP-1 is a secreted protein of 638R used as a loading control. (E) Antagonism assays showing that the two 638R-GA1 transconjugants are defective in killing B. thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 compared to the WT strain using cefoxitin selection plates. (F) Antagonism assays with the transconjugant strains as the target strains to analyze their ability to protect themselves from GA3 T6SS antagonism. 638RΔT6 is unable to antagonize and 638RΔV1ΔV2 (10) and 638R-GA1 ΔV1ΔV2 have both of the GA3 variable regions deleted and are unable to protect themselves. Following co-culture to allow antagonism, 638RΔV1ΔV2 was selected based on integration of the ermG gene into the chromosome, and 638R-GA1 transconjugants are selected based on tetracycline resistance encoded in the GA1 ICE. (G) Volcano plot showing the differentially expressed genes of 638R-GA1 transconjugant 6 compared to WT 638R. The red or green dots identify genes that are downregulated or upregulated, respectively, in both 638R-GA1 transconjugants 5 and 6 (transconjugant 5 volcano plot shown in fig. S4). Full RNASeq data from broth grown bacteria provided in Table S1. Fold change and adjusted p-values or FDRs were calculated by DESeq2 (v. 1.42.0) and/or EdgeR (v. 4.0.1).

GA1 ICE abrogates firing of B. fragilis GA3 T6SS

Because many GA3-containing B. fragilis strains also contain a GA1 ICE, the GA3 T6SS may not be effective in preventing conjugal DNA transfer, contrary to what has been shown in some bacterial species (20, 21). To study the ability of the GA1 ICE to preventing GA3 firing, and the contribution of the GA3 T6SS in preventing conjugal transfer, we quantified the transfer frequency of a GA1 ICE from Bacteroides finegoldii CL09T03C10 (BfineCL09) to a B. fragilis strain that constitutively fires its GA3 T6SS (638R) and to an isogenic strain that cannot fire this weapon (638R ΔT6). We found only a 1.5- to 3.2-fold reduction in GA1 ICE transfer due to GA3 antagonism when five different ratios of donor/target (BfineCL09) to recipient/antagonist (638R or 638RΔT6) were analyzed (Fig. 1C, fig. S3). When the quantity of recipient/antagonist was equal to or exceeded the donor/target (by 5- and 10-fold), there was substantial GA3 T6SS-mediated killing of BfineCL09 (Fig. 1C and fig. S3), yet conjugal transfer was only modestly reduced.

The GA1 ICE integrates into a 6-bp consensus site (9), allowing for its insertion throughout recipient genomes. Analysis of two transconjugants revealed that the GA1 ICE of 638R-GA1 transconjugant 5 inserted between BF638R_4113–4114, and the GA1 ICE of 638R-GA1 transconjugant 6 inserted between BF638R_1192–1193; both of these sites are far from the GA3 T6SS locus (BF638R1970–1994). Analysis of the cells and supernatants of these 638R-GA1 transconjugants confirmed that acquisition of a GA1 ICE inhibits firing of the GA3 T6SS (Fig. 1D). Concurrent with this lack of GA3 firing, both strains lost the ability to antagonize (Fig. 1E), confirming that the acquisition of a GA1 ICE prevents GA3 firing and antagonism. Assays with 638R or 638RΔT6 as antagonist and each 638R-GA1 transconjugant as target showed that both transconjugants protect themselves from GA3 attacks (Fig. 1F), which suggests that they produce GA3 immunity proteins in vitro. Deletion of the effector and immunity genes of the two variable regions of the GA3 T6SS locus of 638R-GA1 transconjugant 6 (ΔV1ΔV2) resulted in a strain that is no longer able to protect itself from antagonism (Fig. 1F). Transcriptomic analysis of wild-type (WT) 638R and 638R-GA1 transconjugants 5 and 6 grown in broth showed notably little genome-wide transcriptional differences owing to acquisition of the GA1 ICE (Fig. 1G, fig S4, data S2) with no significant differences in expression of any of the GA3 T6SS genes (data S2). Therefore, lack of GA3 T6SS firing in vitro in 638R-GA1 is not due to decreased transcription of GA3 genes. Deletion of an operon of genes (BF638R_1955–1952) from the WT 638R strain, which are significantly down-regulated as a result of acquiring GA1 ICE, did not prevent GA3 firing (fig. S5), and therefore the down-regulation of these genes is not the cause of the lack of firing. Transcriptomic analyses also revealed that the GA1 T6SS genes are expressed (data S2) and the GA1 system fires in these transconjugants (Fig. 1D), despite their inability to antagonize in vitro (Fig. 1E).

To show that GA1 ICE inhibition of GA3 firing is a general property, we transferred the GA1 ICE from BfineCL09 to B. fragilis 9343 (fig. S6), which has different effector and immunity genes in the two GA3 variable regions compared with 638R (Fig. 1B). The resulting transconjugants (9343-GA1) were also unable to fire the GA3 T6SS (fig. S6D) and to antagonize (fig. S6E), which demonstrates a general inhibition by GA1 ICE of GA3 T6SS firing.

Genetic region responsible for inhibition of GA3 T6SS firing

To identify the GA1 ICE genes that are responsible for preventing GA3 T6SS firing, we deleted three large regions of the GA1 ICE in 638R-GA1–6, which collectively encompass most of the GA1 ICE except the left side, which contains genes commonly found on Bacteroidales ICE (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the cell fraction and supernatants of these mutants showed that deletions 1 and 2 did not affect GA3 firing, but deletion 3, which removed the GA1 T6SS region and some flanking genes, restored GA3 firing (Fig. 2C), which was not artifactual as a result of cell lysis (fig. S7, C to E). Concurrent with GA3 T6SS firing, the strains regained the ability to antagonize (Fig. 2D). A smaller deletion of this region (deletion 4) that removed only GA1 T6SS genes similarly restored GA3 firing (Fig. 2C) and antagonism (Fig. 2D), which shows that GA3 T6SS firing is inhibited by GA1 T6SS genes in broth-grown cultures. We made nine deletions within the GA1 T6SS locus, removing genes for the transmembrane (TM) complex, baseplate, contractile sheath, and tube as well as other structural genes (Fig. 2, B and F) (22). Deletions of genes encoding the two sheath proteins TssBC, the baseplate proteins TssEF, VgrG that caps the tube, and the RHS effector and immunity genes did not restore GA3 T6SS firing (Fig 2E). Deletion of multiple genes involving the TM complex and baseplate restored partial firing (Fig 2E). We made single deletions of these seven genes and found that the deletion of genes that encode predicted base plate proteins TssG and TssK did not restore GA3 firing (Fig 2G). However, partial firing was restored by deletion of any of the four genes that encode inner membrane-linked components of the TM complex (Fig 2G). This restoration was not increased by deletion of the entire tssC-tagB region (Fig 2E). These data show that the GA1 TM complex is involved in inhibition of GA3 firing.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the GA1 ICE genetic region responsible for quelling GA3 T6SS firing. (A) ORF map of the GA1 ICE of B. finegoldii CL09T03C10 showing the region of the B. fragilis chromosome where the ICE inserted in 638R-GA1 transconjugant 6. Genes of the GA1 T6SS are color coded as shown in fig. S2. Genes on the left side of the ICE involved in conjugation are colored green. tetQ added to the ICE to allow selection of transconjugants is highlighted gold. Large deletions made within this region in 638R-GA1 are indicated. The region comprising the GA1 T6SS locus is underlined. (B) Deletions made in the GA1 T6SS locus of strain 638R-GA1 analyzed in Fig 2E. (C) Western immunoblots of cell lysates and supernatants of WT and 638R-GA1 and large deletion mutants indicated in panel A, probed with antisera to the GA3 and GA1 Hcp proteins, or an antiserum to BSAP-1, a secreted protein of 638R used as a loading control. (D) Antagonism assay using the strains listed on the top as the antagonist and B. thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 used as the target strain. The plates contain cefoxitin and are selective for B. thetaiotaomicron. (E) Western immunoblot performed in a manner similar to panel C except with the mutants shown in panel B. Corresponding lysis control western shown in fig S7C. (F) Schematic of the Bacteroidota T6SS apparatus adapted from Bongiovanni et al. (22) showing outer and inner membranes and localizations of T6SS proteins. Figure made with Biorender.com. (G) Western immunoblot of individual genes encoding components of the baseplate and transmembrane complex. Corresponding lysis control western shown in fig S7D. (H) Western immunoblot showing deletions of genes encoding the GA1 and GA3 T6SS transmembrane complex and their effects on firing of the GA1 T6SS. Corresponding lysis control western shown in fig S7E.

A surprising finding from these analyses is that the GA1 Hcp needle (HcpGA1) is fired when the GA1 baseplate proteins and TM complex genes are deleted (Fig 2, E and G), which suggests that the GA1 tube or sheath apparatus can be assembled on and fired from the GA3 baseplate and TM complex. To confirm this result, we deleted genes tssG-N of the GA3 locus from both 638R-GA1 and 638R-GA1ΔtssG-R(GA1) and confirmed that the GA1 needle is fired when either set of TM genes is present (GA1 or GA3), but not when both are deleted (Fig 2H). Deletion of the tssN-RGA3 or of the entire GA3 T6SS locus resulted in an increase in the amount of HcpGA1 in the supernatant. These combined data suggest that the inhibition of GA3 T6SS firing is due in part to preferential GA1 firing from its machinery. The improved secretion of HcpGA1 when the GA3 locus or TM complex genes are deleted raises the possibilities that GA1 complexes built on the GA3 apparatuses may be less efficiently loaded and fired and/or that hybrid GA1-GA3 TM-baseplate complexes form that hinder firing of both T6SSs.

To study this inhibition visually, we made a TssBGA3-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion by integrating gfp into the native tssBGA3 of both 638R and 638R-GA1, which allowed the sheath to be fluorescently labeled without affecting GA3 function (19). In 638R, many fluorescent complexes are visible that are assembled and fire with movement in the cell as previously reported (movie S1) (19). In 638R-GA1, the fluorescent label is mostly static without obvious sheath-wrapped tubes forming on the membrane (movie S2).

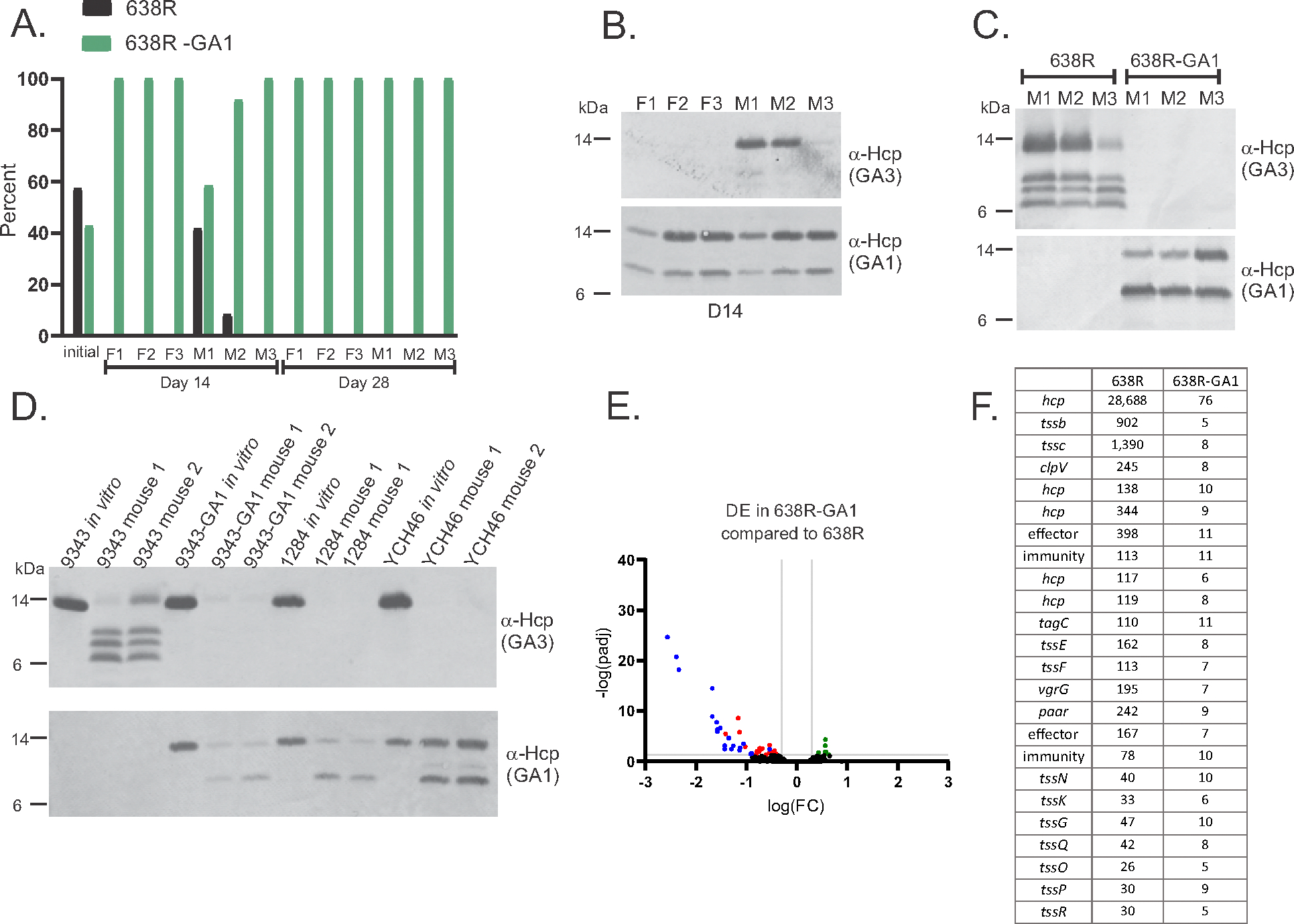

638R-GA1 no longer carries a predicted energetic cost of firing the GA3 T6SS (incurred from contracted sheath disassembly) and protects itself from GA3 toxicity. Based solely on these GA3-based properties, the 638R-GA1 strain may be more fit in a competition assay. To determine whether GA1 ICE acquisition by 638R affects its fitness in vivo, we performed a gnotobiotic mouse competitive gut colonization assay, competing 638R against 638R-GA1. Mice were gavaged with a 1:1 mixture of strains, and bacteria quantified from feces 2- and 4-weeks after gavage. By 2 weeks, the 638R-GA1 strain outcompeted the 638R strain in all six mice (Fig. 3A), with the 638R strain dropping below the detection level in four of the six mice, and by 4 weeks, no 638R was detected in any mice (Fig. 3A). Therefore, in this model, the acquisition of the GA1 ICE provides a competitive advantage to this GA3-containing B. fragilis strain. However, when we assayed for the presence of the GA1 and GA3 Hcp proteins in the fecal material, the results were unexpected and markedly different from in vitro results. For all samples in which strain 638R was below the level of detection, no HcpGA3 was detected in the feces (Fig. 3B), which suggests that 638R-GA1 does not produce HcpGA3 in vivo as it does in vitro. In the two fecal samples from day 14 in which 638R was present at 42% and 8% of the total bacteria, there was detectable HcpGA3 (Fig. 3B), which shows that 638R produces HcpGA3 in vivo but that acquisition of the GA1 ICE prevents its in vivo synthesis. As conclusive proof that 638R-GA1 does not produce HcpGA3 in this in vivo model, we monocolonized gnotobiotic mice with either 638R or 638R-GA1, where they colonized at similar levels of approximately 2 × 1010 to 3 × 1010 colony forming units (CFU) per gram feces and confirmed that synthesis of HcpGA3 is abrogated in 638R-GA1 (Fig. 3C). Passage of 638R-GA1 in vitro after recovery from monocolonized mouse showed restoration of HcpGA3 synthesis (fig. S8), which demonstrates that lack of production in vivo is not due to selection of GA3 mutants. These collective data show that in this in vivo model, the GA1 ICE abrogates HcpGA3 synthesis.

Fig. 3.

GA1 effects on the 638R GA3 T6SS in the mammalian gut. (A) Competitive colonization assay in gnotobiotic mice using three female (F) and three male (M) mice showing the percentage of the two strains in the initial inoculum and then in the feces at day 14 and day 28 post-gavage. (B) Western immunoblot analysis of day 14 fecal samples from mice from the competition experiment in panel A. (C) Western immunoblot analysis of fecal samples from three mice mono-colonized with either 638R or 638R-GA1 after 7 days of colonization. (D) Western immunoblot analysis of cells from broth-grown bacteria or from fecal samples from mice mono-colonized with three additional B. fragilis strains containing a GA3 T6SS and a GA1 ICE. (E) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes of 638R-GA1 compared to 638R from feces of mice monocolonized with each strain. Blue dots indicate genes of the GA3 T6SS. Red dots indicate other significantly downregulated genes and green dots indicate significantly upregulated genes (significance defined as at least 2.0-fold and adjusted p-value (DESeq2) and FDR (EdgeR) both were less than or equal to 0.05). (F) Transcript per kilobase million (TPM) values for the GA3 T6SS genes from feces of mice monocolonized with 638R or 638R-GA1.

To determine if in vivo inhibition of GA3 synthesis is a general property of B. fragilis strains that harbor both a GA3 locus and GA1 ICE, we monocolonized mice with 9343, 9343-GA1, or two B. fragilis strains, 1284 and YCH46, that naturally contain both a GA3 locus and GA1 ICE (Fig. 1A and fig. S2). We found that none of the strains that naturally contain a GA1 ICE, nor those that received the GA1 ICE by in vitro transfer, produced the HcpGA3 in vivo (Fig. 3D), confirming that the GA1 ICE encodes a function that shuts down synthesis of HcpGA3 in vivo. Transcriptomic analysis of fecal samples from mice monocolonized with 638R or 638R-GA1 revealed robust transcription of the GA3 genes from 638R but near-compete abrogation of their transcription in 638R-GA1 (Fig. 3, E and F, and data S3).

TetRGA1 inhibits transcription of GA3 T6SS locus in vivo

GA1, GA2, and GA3 T6SS loci each contain an adjacent gene that encodes a transcriptional repressor of the TetR family (8, 23). GA1 ICEs are highly conserved (8) and invariably contain the tetR in the vicinity of the T6SS locus (Fig. 2A and fig. S2). A TetR repressor encoded on a mobile plasmid that confers multidrug resistance inhibits expression of a T6SS locus of Acinetobacter baumannii (21), although this protein has no sequence similarity to TetRGA1. We deleted tetRGA1 from 638R-GA1 and monocolonized mice and found that this deletion restored synthesis of HcpGA3 (Fig. 4A). To broaden the relevance of this discovery, we deleted tetRGA1 from 9343-GA1, and from the natural GA1-GA3-containing strain Bf1284, and found that HcpGA3 synthesis is restored in vivo when tetRGA1 is deleted in all these GA3-GA1 ICE strains (Fig 4A), whether natural isolates or strains created in the lab. Transcriptional analysis of 638R-GA1ΔtetRGA1 from monocolonized mouse feces revealed that the genes that were significantly downregulated in vivo owing to acquisition of the GA1 ICE were restored when tetRGA1 was deleted (Fig. 4B and data S3), such that comparison of the in vivo transcriptome of 638R with that of 638R-GA1ΔtetRGA1 showed only five differentially expressed 638R genes (tab 5 of data S3, Fig. 4C). An interesting finding is that deletion of tetRGA1 decreased transcription of one of the three operons (hcp-rhs) of the GA1 T6SS locus (data S3). The deletion of tetRGA1 did not restore GA3 firing to 638R-GA1 when bacteria were grown in broth (fig. S7F) and therefore does not have a role in preventing firing of the GA3 T6SS.

Fig. 4.

Analyses of regulation and competition in vivo. (A) Western immunoblot analysis of Hcp synthesis in WT B. fragilis strains, GA3-GA1 B. fragilis strains, and tetRGA1 deletion mutants from feces of mono-colonized mice. Two mice were colonized with each ΔtetRGA1 mutant. Complementation of the tetRGA1 for native GA3-GA1 containing B. fragilis strain 1284 is shown in fig S9A. (B) Volcano plot showing differential expression of genes of 638R-GA1ΔtetRGA1 compared to 638R-GA1 from feces of mice monocolonized with each strain. Blue dots indicate genes of the GA3 T6SS locus. Brown dots indicate genes of the GA1 T6SS locus (significance defined as at least ≥2 -fold and adjusted p-value (DESeq2 v. 1.42.0) and FDR (EdgeR(v. 4.0.1) both were less than or equal to 0.05). (C) Volcano plot showing differential expression of genes of 638R compared to 638R-GA1ΔtetRGA1 from feces of mice monocolonized with each strain. Fold change and adjusted p-values or FDRs were calculated by DESeq2 (v. 1.42.0) and/or EdgeR (v. 4.0.1). (D) Competitive colonization assay in gnotobiotic mice competing 638R versus 638R-GA1ΔtssBCGA1 in three female (F) and three male (M) mice. The percentage of the two strains in the initial inoculum and then in the feces at day 14 and day 28 post-gavage is shown. (E, F) Competitive colonization assay in gnotobiotic mice competing 638RΔV1ΔV2 against either 638R-GA1Δ4ΔtetRGA1 or 638R-GA1ΔRHSΔtetRGA1 in three female (F) and three male (M) mice. The percentage of the two strains in the initial inoculum and then in the feces at day 14 post-gavage is shown. (G) Number of 9343-GA1 transconjugants arising over time in gnotobiotic mice colonized with equal numbers of 9343ermG and B. finegoldii (GA1-tetQ) in four mice. M1 and M2 were co-housed as were M3 and M4. The percentages of each inoculated strain at the end of the experiment are shown in fig S9B.

The GA3 T6SS of 638R and other B. fragilis strains are potent weapons in vivo (10–12), yet the in vivo competitive colonization assay between 638R and 638R-GA1 revealed that 638R-GA1 outcompetes the parental 638R strain in the gnotobiotic mouse gut (Fig. 3A), which is an unexpected result because the GA3 immunity genes are not expressed in the mouse gut in 638R-GA1. Therefore, the GA1 T6SS may be antagonistic in vivo and may be effective at competing against WT 638R that can fire the GA3 weapon, especially when delivered from the 638R isogenic strain. To test if GA1 antagonism explains the 638R-GA1 competitive colonization advantage, we used the 638R-GA1 mutant in which the GA1 tssBC, encoding both sheath proteins, is deleted, abrogating GA1 T6SS firing (Fig. 2E). Competition of this mutant (638R-GA1ΔtssBCGA1), against WT 638R showed that 638R-GA1ΔtssBCGA1 is outcompeted (Fig. 4D). These data show that an active GA1 T6SS in a GA3-containing B. fragilis strains allows it to outcompete the isogenic ancestral strain in vivo.

TetR-family repressors bind specific ligands and removes them from their DNA targets, which relieves repression. In the gut, under conditions during which such derepression occurs, the second level of antagonistic repression, that is, the inhibition of firing, which is not TetR-dependent, would keep the GA3 T6SS inactive. To confirm that the second level of inhibition, that is, lack of firing, occurs in the mouse gut, we performed two competitive colonization assays. As the target strain, we used the isogenic 638R strain deleted for the two GA3 variable regions containing the effector and immunity genes (638R ΔV1ΔV2), which is unable to antagonize using the GA3 T6SS or protect itself from GA3 antagonism (10) (Fig. 1F). We tested competition between 638RΔV1ΔV2 and 638R-GA1ΔtetR(GA1)Δ4, which is deleted for tetR and the entire GA1 T6SS (Fig 2A), allowing GA3 antagonism (transcription and firing), but not GA1 antagonism. This strain rapidly outcompeted 638RΔV1ΔV2, as expected, using its GA3 T6SS (Fig 4E). Next, we performed the same experiment but used 638R-GA1ΔtetR(GA1)ΔRHS as the antagonizing strain, which has a smaller deletion of the GA1 T6SS locus compared to the first mutant, retaining TM genes involved in inhibition of GA3 firing. GA1 is not able to fire in this strain (Fig 2E), but the GA3 locus is transcribed owing to the deletion of tetRGA1. If the second level of GA3 inhibition (lack of firing) occurs in the mammalian gut, 638R-GA1ΔtetR(GA1)ΔRHS will not antagonize 648RΔV1ΔV2 and will not outcompete it. We found that not only is 638RΔV1ΔV2 not outcompeted, it also outcompetes 638R-GA1ΔtetR(GA1)ΔRHS (Fig 4F), which confirms that the GA1 T6SS locus prevents GA3 firing in vivo, even when the GA3 T6SS locus is transcribed.

GA1 ICE transfer occurs in the human gut because a large percentage of B. fragilis stains have both a GA3 T6SS locus and a GA1 ICE. Indeed, we found that the GA1 ICE is presently one of the most transferred conserved MGE in industrialized human populations (9) and that GA3 T6SS antagonism only slightly reduces, but does not prevent, GA1 ICE transfer (Fig 1C). To experimentally confirm that the GA1 ICE transfers to a GA3-containing B. fragilis strain in the mammalian gut, we cocolonized four mice in two cages with B. finegoldii GA1-tetQ and B. fragilis 9343ermG and tracked transconjugants (9343-GA1) over time. Transconjugants can be detected in the feces as early as 2 weeks after cocolonization, and by 8 weeks, transconjugants in the mice of one cage approached 107 CFU per gram of feces and in the other cage were >108 CFU per gram of feces (Fig 4G). This rapid increase in transconjugant abundance could be attributed to continued transfer of the ICE, expansion of transconjugants due to selection, or both. Because the GA1 ICE inserts at a 6-bp site that is present throughout the genome, we tracked GA1 ICE insertion sites and the fate of transconjugants over time by pooled transconjugant genome sequencing. The number of transconjugants sequenced from each mouse at each time point varied; however, the greatest number of distinct transconjugants detected from any one mouse was 14, and this included an analysis with 2375 transconjugant colonies (data S4). There were many identical transconjugants between the two mice in the same cage owing to coprophagy. Some transconjugants decreased in the percentage of total transconjugants over time and others increased. In both cages, a predominant transconjugant emerged in the mice by week 12. In cage 1, a single transconjugant comprised 96% and 98% of the transconjugant population and in cage 2, the predominant transconjugant comprised 59% and 82% of the transconjugant population (tab 1 of data S4). These data show ICE transfer occurs quickly in the mammalian gut but that specific transconjugants are selected and predominate in a population.

Discussion

The extensive transfer of the GA1 ICE among GA3-sensitive Bacteroidales species increases opportunities for transfer of this ICE into GA3-containing B. fragilis strains. Antagonism mediated by the newly acquired GA1 T6SS then allows the B. fragilis GA1-transconjugant to outcompete the progenitor B. fragilis strain using its GA1 T6SS. Acquisition of this ICE thereby changes a major Bacteroidales antagonist to one that no longer antagonizes other GA1-containing species of the ecosystem yet is equipped with the GA1 T6SS to collectively defend the ecosystem against sensitive invaders.

The ecological consequences and fitness outcomes of this DNA transfer to both the recipient and the community likely depend on numerous factors, including the site of GA1 ICE insertion, the composition of the community, how many of the community’s Bacteroidales species contain the GA1 ICE, and the potency of the GA3 and GA1 T6SS toxins. In the human gut, when a putative TetRGA1 ligand is present, the GA3-GA1 strain will likely have an additional cost of producing GA3 proteins, which may also lead to reduced GA1 antagonism by transmembrane complex interference. In addition, some Bacteroidales strains contain MGEs with acquired interbacterial defense systems that contain genes encoding immunity proteins to GA1, GA2, and GA3 toxic effectors (16). Therefore, the dynamics of which weapon would win in a battle of B. fragilis strains is highly strain and ecosystem dependent. As the catalog of MGEs of the gut microbiota and analyses of their phenotypes increases (16, 17, 24–29), it is important to consider that the effects these elements have on the native genome may be as ecologically relevant as the phenotypes encoded by the MGE themselves.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to C. Metcalfe, C. Woodson, and V. Burgo of the DFI Microbiome Metagenomics Facility for RNA sequencing and whole genome sequencing. We thank K. Hutt, K. Kolar, K. Campbell, J. Kasper and B. Theriault of the UChicago GRAF center for assistance with gnotobiotic mouse experimentation and S. Light for helpful discussions. We thank H. Chu for providing strain YCH46. A few strains used in this study were obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH as part of the Human Microbiome Project.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health grant K99AI167064 (LGB)

National Institutes of Health grant R01AI132580 (BB)

National Institutes of Health grant R01AI093771 (LEC)

Duchossois Family Institute (LEC)

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All materials created in this study are available from the corresponding author. Constructs, strains, plasmids and mutants are available from Laurie Comstock under a materials transfer agreement (MTA) with the University of Chicago. The genomes sequenced as part of this study and the RNASeq data and Illumina reads for insertion site mapping (SRA SUB14693552) have been deposited with NCBI under BioProject ID PRJNA982086. All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Zitomersky NL, Coyne MJ, Comstock LE, Longitudinal analysis of the prevalence, maintenance, and IgA response to species of the order Bacteroidales in the human gut. Infect Immun 79, 2012–2020 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco-Miguez A et al. , Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nature Biotechnol, 11, 1633–1644 (2023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faith JJ et al. , The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science 341, 1237439–1–1237439–8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Coyne MJ, Comstock LE, An antimicrobial protein of the gut symbiont Bacteroides fragilis with a MACPF domain of host immune proteins. Mol Microbiol 94, 1361–1374 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatzidaki-Livanis M et al. , Gut symbiont Bacteroides fragilis secretes a eukaryotic-like ubiquitin protein that mediates intraspecies antagonism. mBio 8, e01902–17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shumaker AM, Laclare McEneany V, Coyne MJ, Silver PA, Comstock LE, Identification of a fifth antibacterial toxin produced by a single Bacteroides fragilis strain. J Bacteriol 201, e00577–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao Y et al. , A common pathway for activation of host-targeting and bacteria-targeting toxins in human intestinal bacteria. mBio 12, e0065621 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne MJ, Roelofs KG, Comstock LE, Type VI secretion systems of human gut Bacteroidales segregate into three genetic architectures, two of which are contained on mobile genetic elements. BMC Genomics 17, 1–21 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Bayona L, Coyne MJ, Comstock LE, Mobile Type VI secretion system loci of the gut Bacteroidales display extensive intra-ecosystem transfer, multi-species spread and geographical clustering. PLoS Gen 17, e1009541 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Geva-Zatorsky N, Comstock LE, Bacteroides fragilis type VI secretion systems use novel effector and immunity proteins to antagonize human gut Bacteroidales species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 3627–3632 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wexler AG et al. , Human symbionts inject and neutralize antibacterial toxins to persist in the gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 3639–3644 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecht AL et al. , Strain competition restricts colonization of an enteric pathogen and prevents colitis. EMBO Rep 17, 1281–1291 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brito IL et al. , Mobile genes in the human microbiome are structured from global to individual scales. Nature 535, 435–439 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao H, Coyne MJ, Garcia-Bayona L, Comstock LE, Analysis of Effector and Immunity Proteins of the GA2 Type VI Secretion Systems of Gut Bacteroidales. J Bacteriol 204, e0012222 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosch DE, Abbasian R, Parajuli B, Peterson SB, Mougous JD, Structural disruption of Ntox15 nuclease effector domains by immunity proteins protects against type VI secretion system intoxication in Bacteroidales. mBio, e0103923 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross BD et al. , Human gut bacteria contain acquired interbacterial defence systems. Nature 575, 224–228 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frye KA, Piamthai V, Hsiao A, Degnan PH. Mobilization of vitamin B(12) transporters alters competitive dynamics in a human gut microbe. Cell Rep 37, 110164 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon K, Sonnenburg J, Salyers AA, Unexpected effect of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon, CTnDOT, on chromosomal gene expression in its bacterial host. Mol Microbiol 64, 1562–1571 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Bayona L et al. , Nanaerobic growth enables direct visualization of dynamic cellular processes in human gut symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 24484–24493 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho BT, Basler M, Mekalanos JJ, Type 6 secretion system-mediated immunity to type 4 secretion system-mediated gene transfer. Science 342, 250–253 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Venanzio G et al. , Multidrug-resistant plasmids repress chromosomally encoded T6SS to enable their dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 1378–1383 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bongiovanni TR et al. , Assembly of a unique membrane complex in type VI secretion systems of Bacteroidota. Nature Comm 15, 429 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuthbertson L, Nodwell JR, The TetR family of regulators. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77, 440–475 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoemaker NB, Vlamakis H, Hayes K, Salyers AA, Evidence for extensive resistance gene transfer among Bacteroides spp. and among Bacteroides and other genera in the human colon. Appl Environ Microbiol 67, 561–568 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyne MJ et al. , A family of anti-Bacteroidales peptide toxins wide-spread in the human gut microbiota. Nature Comm 10, 3460 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans JC et al. , A proteolytically activated antimicrobial toxin encoded on a mobile plasmid of Bacteroidales induces a protective response. Nature Comm 13, 4258 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pudlo NA et al. , Diverse events have transferred genes for edible seaweed digestion from marine to human gut bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 30, 314–328 e311 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zlitni S et al. , Strain-resolved microbiome sequencing reveals mobile elements that drive bacterial competition on a clinical timescale. Genome Med 12, 50 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boiten KE et al. , Characterization of mobile genetic elements in multidrug-resistant Bacteroides fragilis isolates from different hospitals in the Netherlands. Anaerobe 81, 102722 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantosti A, Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Kasper DL, Immunochemical characterization of two surface polysaccharides of Bacteroides fragilis. Infect Immun 59, 2075–2082 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Bayona L, Comstock LE, Streamlined genetic manipulation of diverse Bacteroides and Parabacteroides isolates from the human gut microbiota. mBio 10, e01762–19. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA, Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nature Biotechnol 37, 540–546 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE, Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comp Biol 13, e1005595 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyatt D et al. , Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 119 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seemann T, Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danecek P et al. , Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, giab008 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinlan AR, Hall IM, BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK, edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito T et al. , Genetic and biochemical analysis of anaerobic respiration in Bacteroides fragilis and its importance in vivo. mBio 11, e03238–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schindelin J et al. , Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thevenaz P, Ruttimann UE, Unser M, A pyramid approach to subpixel registration based on intensity. IEEE Trans Image Process 7, 27–41 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Z.j. et al. , Comprehensive analyses of a large human gut Bacteroidales culture collection reveal species and strain level diversity and evolution. Cell Host Microbe. in press. on-line Sept 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuwahara T et al. , Genomic analysis of Bacteroides fragilis reveals extensive DNA inversions regulating cell surface adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 14919–14924 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All materials created in this study are available from the corresponding author. Constructs, strains, plasmids and mutants are available from Laurie Comstock under a materials transfer agreement (MTA) with the University of Chicago. The genomes sequenced as part of this study and the RNASeq data and Illumina reads for insertion site mapping (SRA SUB14693552) have been deposited with NCBI under BioProject ID PRJNA982086. All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.