Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies are powerful therapeutic, diagnostic, and research tools. Methods utilized to generate monoclonal antibodies are evolving rapidly. We created a transfectable linear antibody expression cassette from a 2-h high-fidelity overlapping PCR reaction from synthesized DNA fragments. We coupled heavy and light chains into a single linear sequence with a promoter, self-cleaving peptide, and poly(A) signal to increase the flexibility of swapping variable regions from any sequence available in silico. Transfection of the linear cassette tended to generate similar levels to the two-plasmid system and generated an average of 47 μg (14–98 μg) after 5 days in 2 ml cultures with 15 unique antibody sequences. The levels of antibodies produced were sufficient for most downstream applications in less than a week. The method presented here reduces the time, cost, and complexity of cloning steps.

Keywords: Monoclonal antibodies, B cells, Influenza, Biolayer interferometry, Confocal microscopy

1. Introduction

Antibodies are essential for vaccine mediated protection (Plotkin, 2010; Plotkin, 2020), diagnostics (Borrebaeck, 2000), therapeutics (Lu et al., 2020) and research (Goldman, 2000). Monoclonal antibodies (mAb), those derived from single B cell clones, can be used as therapeutics for emerging infectious diseases, as demonstrated recently during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (Corti et al., 2021; Almagro et al., 2022). Antibodies are secreted proteins that naturally circulate throughout the body. They stem from cell-surface proteins called B cell receptors (BCR) that define the B cell hematopoeitc lineage. During B cell development, the DNA that encodes the BCR heavy and light chains is derived from unique recombination events of exons named variable (V), diversity (D), joining (J), and constant (C) regions. Randomly inserted nucleotides are added between VDJ junctions for heavy chains and VJ junctions for light chains with terminal nucleotidyl transferase (TdT) creating even more genetic diversity. Furthermore, the two chains then pair together in duplicate to create a unique BCR for each B cell, generating anywhere from a trillion to a million trillion (10 (Steinitz et al., 1977)–10 (Zhou et al., 2020)) variations (Briney et al., 2019). The result is a sufficient amount of antibody diversity to bind almost any antigenic shape our immune system may encounter throughout life (Tonegawa, 1983). Further antibody binding affinity evolves through somatic hyper-mutation of B cell BCR DNA, a process akin to natural selection often called affinity maturation. Competition for antigen binding determines the selection of B cells with higher affinity mutations, leading to their clonal expansion and development into memory B cells and antibody secreting cells such as plasmablasts and short- and long-lived plasma cells (De Silva and Klein, 2015). Sequencing BCRs and creating the antibodies they encode in vitro provides individual monoclonal antibodies for research, diagnostic, prophylactic or therapeutic applications.

Methods employed to examine monoclonal antibodies in vitro have developed significantly since Milstein and Kohler’s Nobel prize winning hybrid cell technique published in 1975 (Kohler and Milstein, 1975). Notable methods include hybridomas and hetero-hybrids, B cell transformations with Epstein-Barr virus (Steinitz et al., 1977) and limiting dilution (Traggiai et al., 2004), multiplex PCR of single cells cloned into plasmids or linear cassettes (Liao et al., 2009; Tiller et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2013; von Boehmer et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2020; Gieselmann et al., 2021; Yoshioka et al., 2011), phage, yeast or bacterial display of heavy and light chain cDNA followed by a selection process (Mazor et al., 2007; Daugherty et al., 1999; McCafferty et al., 1990; Wang et al., 2018), or direct DNA synthesis of in silico antibody sequences cloned into plasmids (Gilchuk et al., 2021). Multiple strategies have been developed, each with advantages and limitations for end users.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. ELISA

ELISA plates were coated with recombinant H3 hemagglutinin from A/Singapore/INFIMH-16–0019/2016 (H3N2) at 1–10 μg or 1 μg of goat anti-human IgG in PBS in 100 μL per well overnight at 4 °C or for 1–3 h at 37 °C. Plates were washed three times in wash buffer (PBS-Tween (0.05)) and blocked with 4 % BSA in wash buffer for one hour at 37 °C, and then washed three times with wash buffer. Supernatants or purified antibodies were added in 2–3-fold dilutions and incubated for two hours at 37 °C or overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, the plates were washed three times with wash buffer and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were added (HRP-anti-human IgG) for one hour at room temperature, and then washed three times in wash buffer. 50 μL of high sensitivity TMB (3,3′, 5,5;-tetramethylbenzidine) solution (BioLegend®; Cat# 421501) was added to each well and stopped by adding 50 μL of stop solution, and subsequently read at 450 nm using a BioTek Cytation 7. Final antibody concentrations were determined by using standard curves generated from monoclonal antibodies with known concentrations, and interpolated in GraphPad Prism 8.

2.2. Antibody expression cassettes

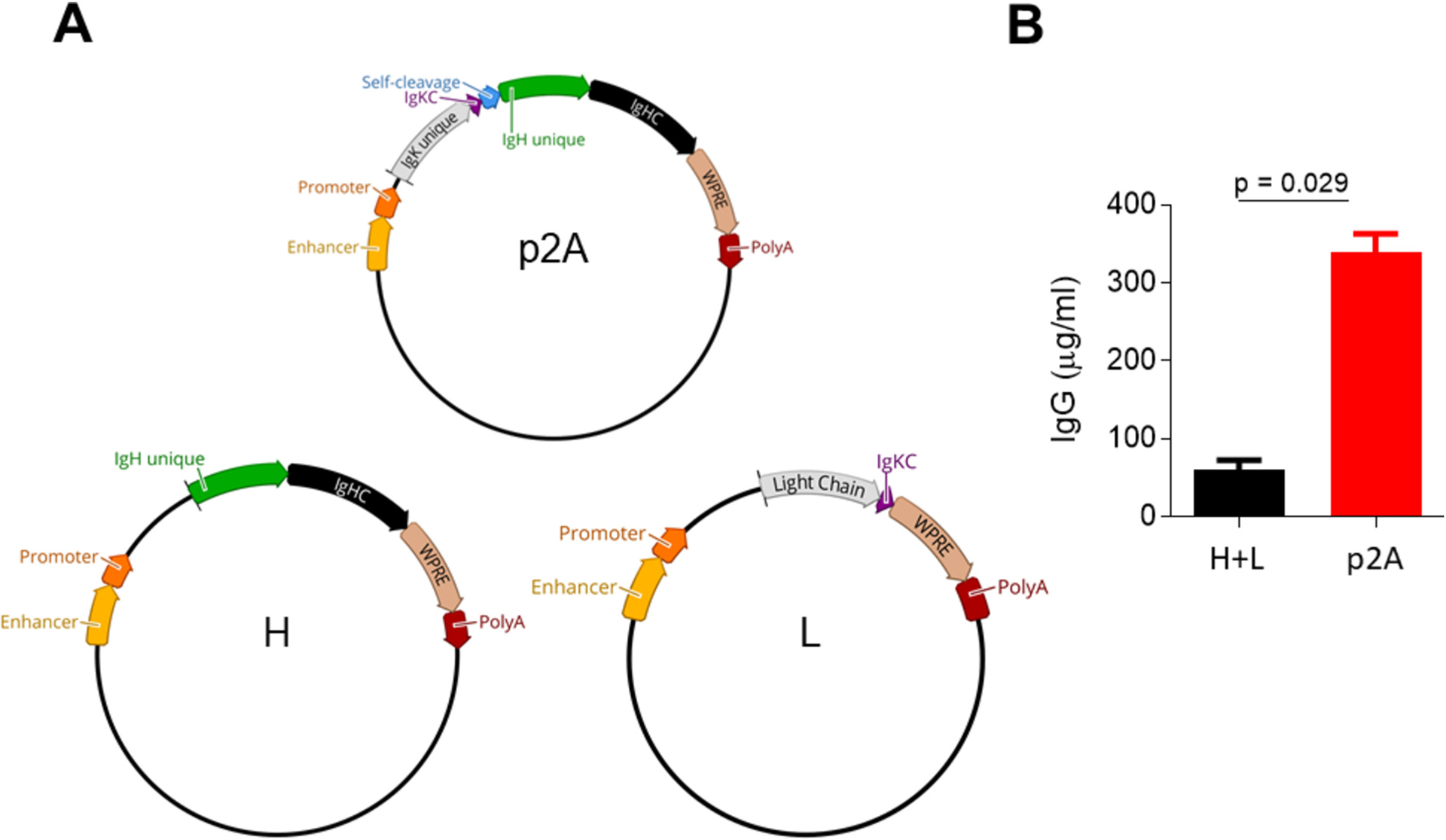

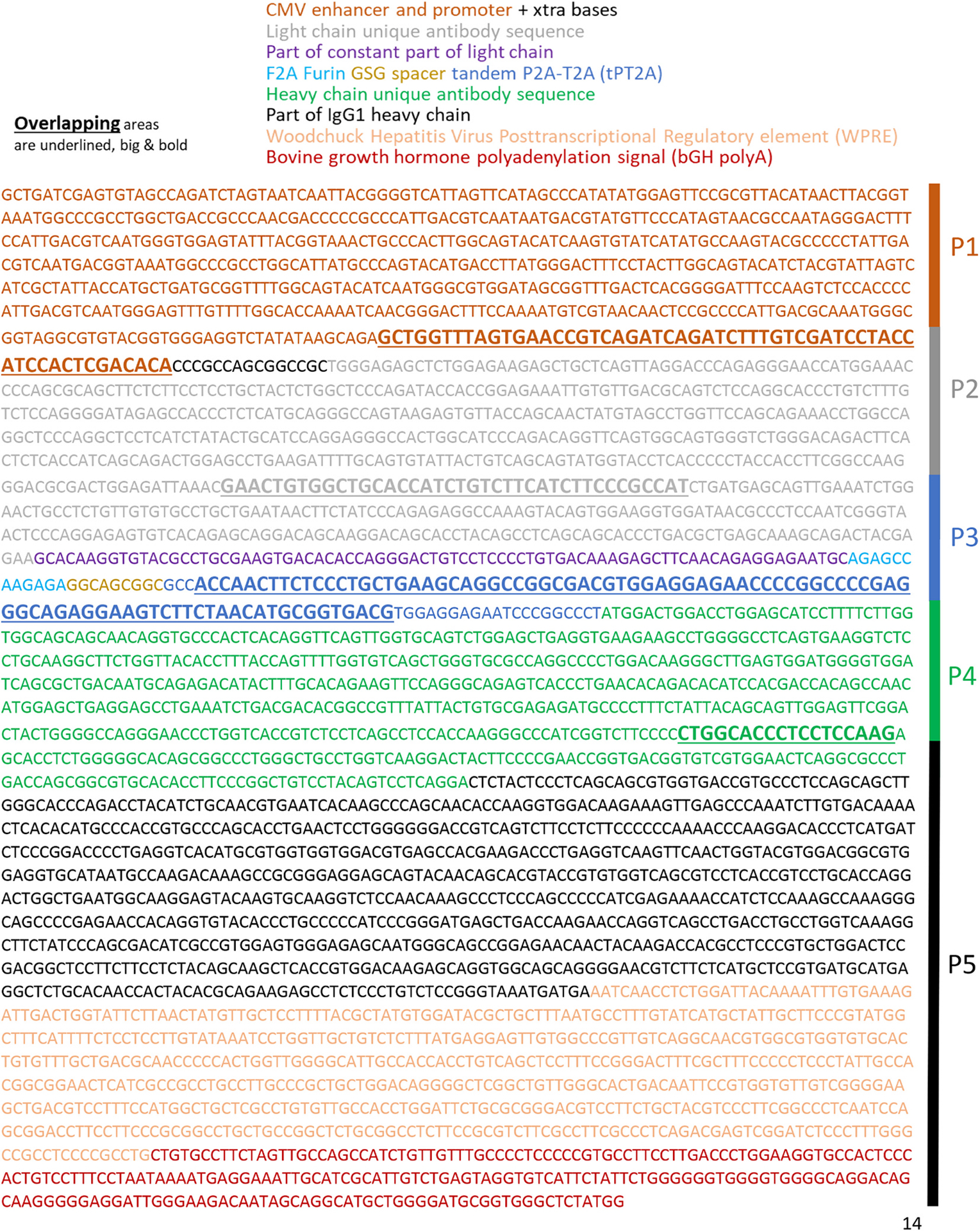

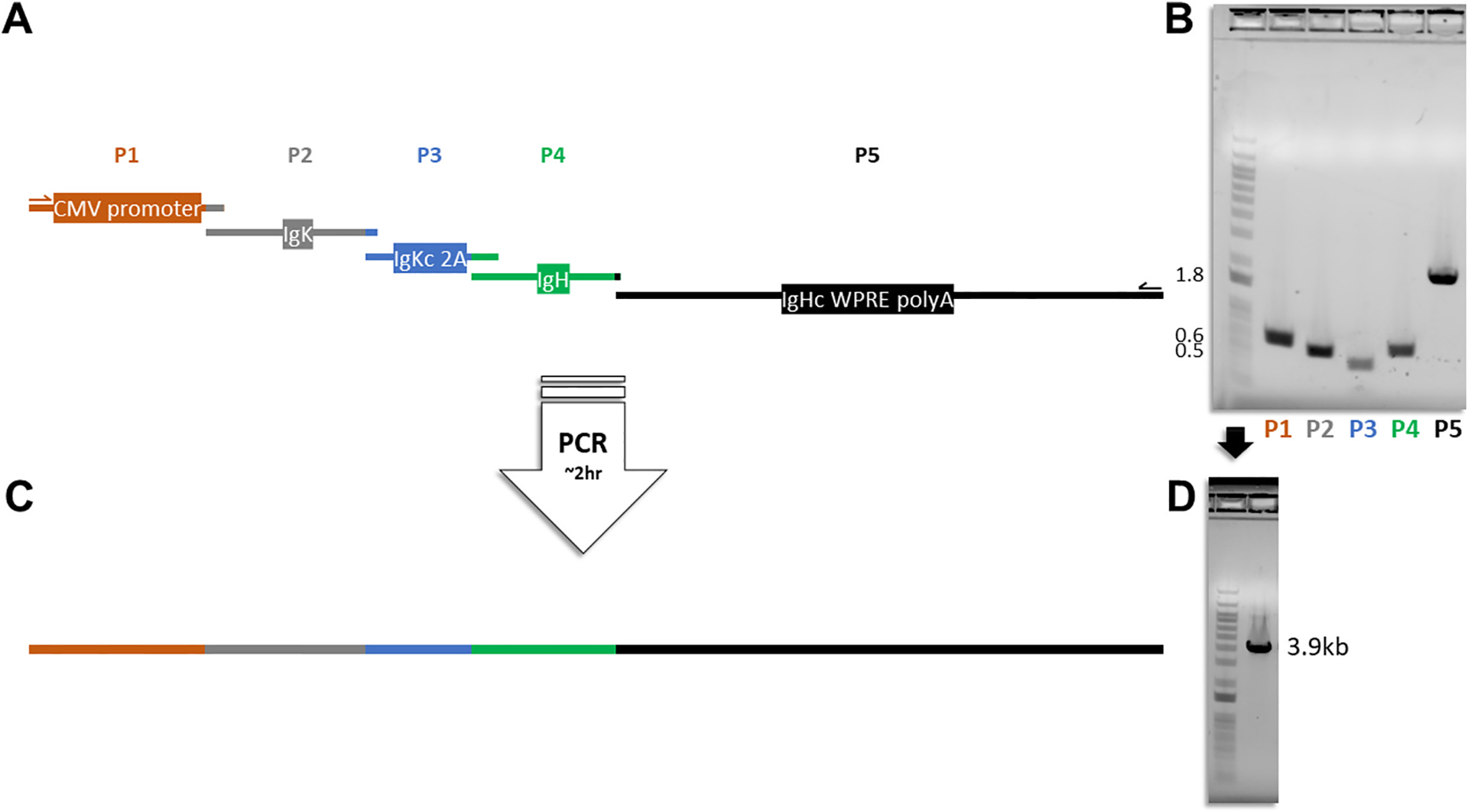

Plasmids containing antibody expression cassettes were created first as heavy and light chains separately in an expression plasmid generated at TwistBiosciences (pTwist CMV; Fig. 1A), and as various custom generated single plasmids in the same backbone. The plasmid showing the best expression was taken forward (Fig. 1A) and either amplified from the plasmid or in a 5-piece PCR reaction which contained the parts shown in Fig. 3: a CMV promoter, CMV enhancer, a GSG spacer, kappa light chain sequence with genes of a previously unknown H3-specific antibody. The kappa light chain constant portion was followed by a Furin cleavage site (Chng et al., 2015) to remove excess residues from the self-cleaving tandem P2A-T2A peptide (Liu et al., 2017) and a GSG spacer. Lambda light chain (IGLC2) was also used (4 mAbs; 30–63 μg/ml) with an alternative piece 3 (P3). Subsequent sequence included an IgG1 isotype heavy chain starting from the signal peptide. The rest of the human IgG1 constant region, followed by the WPRE to potentially enhance RNA stability, transcriptional termination, and large RNA shuttling outside the nucleus, followed by the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal. Once the single plasmid sequence was optimized, primers were designed to amplify a linear expression cassette (Table S1) using the Platinum™ SuperFi II DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen™; Cat# 12361010).

Fig. 1. Plasmid maps and expression levels.

a, Single plasmid (p2A; top) antibody expression cassette along with heavy (H; bottom left) and light (L; bottom right) chain plasmids from the two-plasmid system. b, IgG expressedfrom plasmids as either co-transfected heavy and light chains (black; H + L) or a single expression cassette (red; p2 A) with 1 μg/ml transfections. Plasmid elements include the following: Enhancer and Promoter = CMV; IgK unique = immunoglobulin kappa (light) chain sequence different for each antibody; IgKC = kappa (light) constant; Self-cleavage = Furin site, GSG spacer, and tandem P2 A T2 A sequence; IgHC = heavy chain constant; WPRE = woodchuck posttranscriptional regulatory element; PolyA = poly(A) signal; IgG = immunoglobulin G isotype.

Fig. 3. Detailed example of an antibody expression cassette DNA sequence.

An example antibody expression cassette sequence that is colour-coded to the sections listed above the sequence. Underlined in large bold text are the overlapping portions for the 5-piece overlapping PCR along with the scheme from Fig. 1 on the right. Naturally occurring signal peptides derived from each antibody sequence were included for both heavy and light chains at the coding region starts (ATG). Translation is shown in Fig. S1.

2.3. Overlapping PCR

The linear antibody expression cassette derived from the single plasmid, once tested for the ability to produce antibodies upon transfection, was used to create multiple PCR pieces through trial and error of various primers and sequence locations to test an overlapping PCR reaction where new antibody sequences could be swapped in and out of the heavy and light chain variable portions as described in the text and in further detail in supplementary information (Table S1; Fig. 2; Fig. 3). The overlapping areas for heavy and light chain sequences also focused on regions of least diversity to make sure the method is adaptable to any sequence. The pieces that define the antibody clone (P2 and P4) were generated from in silico sequences derived from sorting B cells and 10× Chromium DNA synthesis with TwistBiosciences. Various cycling conditions were tested and the final conditions were as follows: 1) 98 °C 1 min 2) 98 °C 30 s 3) 55 °C 2 min 4) 72 °C 5 min, 5) 98 °C 30 s 6) 60 °C 30 s 7) 72 °C 1 min 8) Go to #5 for 25–34× cycles 9) 72 °C 5 min 10) 4 °C hold. For a 25 μL reaction, 5× buffer (5 μL), 10 mM forward [GCTGATCGAGTGTAGCCAGA] and reverse [CATA-GAGCCCACCGCATCC] primers (1.25 μL each), 10 mM dNTP (0.5 μL), 2 ng/ml of P1/P3/P5 (0.5 μL), 5 ng/ml of P2/P4 (0.5 μL), Platinum™ SuperFi II DNA Polymerase (0.5 μL; Invitrogen™; Cat# 12361010), nuclease-free water (14 μL). Amplicons were then taken forward by multiple methods used to gel extract or purify PCR products including ChargeSwitch PCR Clean-Up Kit (Invitrogen™; Cat: CS12000), E-Gel™ CloneWell™ II Agarose Gels with SYBR Safe, 0.8 % (Invitrogen™ Cat# G661818), and GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific™; Cat# K0721). PCR products were run on DNA gels on an Invitrogen™ E-Gel™ iBase™ with 0.8 %–2 % E-gels and visualized only under blue light. Images were taken with the GE Amersham™ Imager 680.

Fig. 2. Generation of a linear antibody expression cassette from an overlapping PCR.

a, Diagrammatic illustration showing the five pieces in correct proportional length to base pair sizes that go into making the linear expression cassette: (P1) CMV promoter and enhancer; (P2) immunoglobulin kappa chain variable portion (IgK); (P3) immunoglobulin kappa chain constant (IgKc) portion, Furin 2 A recognition site, GSG spacer, tandem P2A-T2A (2A) self-cleaving peptide; (P4) immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IgH) portion; (P5) immunoglobulin heavy chain constant (IgHc) region, woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE), and bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal (polyA). b, P1-P5 DNA segments run on an agarose gel with a 1 kb plus DNA ladder prior to overlapping PCR; Nearest band size numbers are shown in kilobases. c, Full linear antibody expression cassette containing P1-P5 and d, run on an agarose gel with a 1 kb plus DNA ladder.

2.4. Expression of monoclonal antibodies

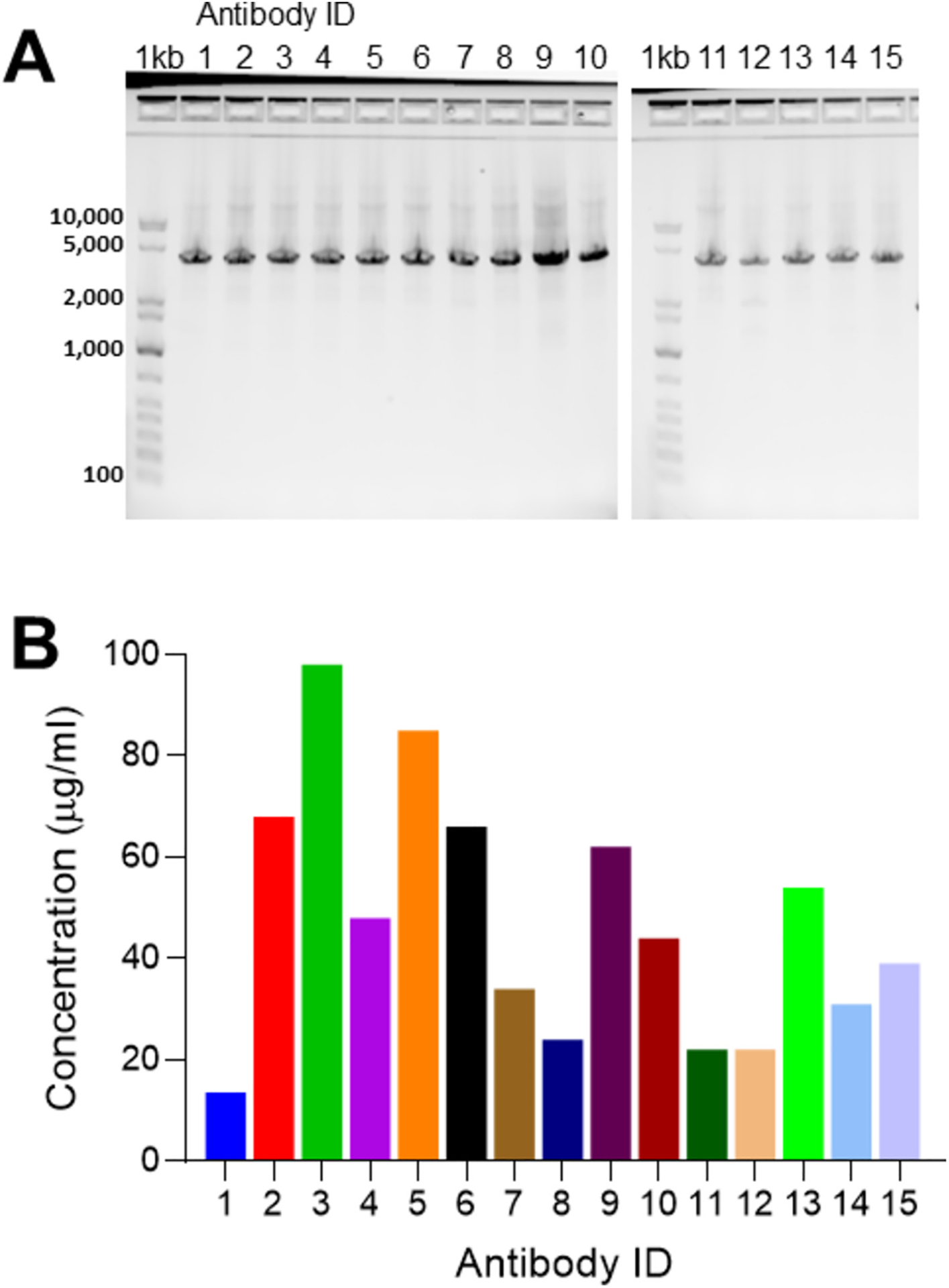

Antibodies were generated by transfecting plasmids or single PCR amplicons (0.5 to 1 μg/ml) described in the manuscript with the Expi293F™ Expression System (ThermoFisher Scientific; Cat# A14635) per manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications described here below. Generally, 6-well plates were used with 4 ml per well often representing 1–4 replicates for each condition using the Benchmark Incu-shaker mini with 8 % carbon dioxide with a rotational speed of 125 rpm. Supernatants were harvested 5 to 8 days post-transfection, spun down at 3,000–4,000 rcf for 20 min, 0.22 μm sterile filtered and stored at 4 °C until processed through rProtein A Sepharose® Fast Flow antibody purification resin (Cytiva™; Cat: 17–1279–01). mAbs were buffer exchanged into PBS using Amicon Ultra-4 or 15 tubes with molecular weight cut-offs of 15, 50, and 100 kD. The controls were transfection supernatants of either no DNA as negative controls, VRC-01 IgG1 antibody from heavy and light chain plasmids as positive controls, or an antibody expression construct that produced predominantly light chain protein. A number of variables may impact the amount of antibody produced using this protocol, including but not limited to DNA purity and concentration. For example, the amount of DNA used for transfection in Fig.6B varied between 1.6 μg and 2.3 μg and correlated with antibody expressed (Fig. S2; Spearman r = 0.53; p = 0.02). Other factors are day of harvest, condition of cells, passage number of cells, incubator conditions, and downstream concentration steps. To control for variations in cell culture conditions, comparisons of antibody levels in the text and figures were performed simultaneously under the same conditions as much as possible, with at least 3 replicates for each sample and 1 to 2 replicates of controls.

Fig. 6. Antibody generation and expression of 15 unique sequences.

a, GelPilot® 1 kb Plus DNA ladder (1 kb) and 15 amplifications of 15 unique mAb sequences all at 3.9 kb all the way across, and b, their concentrations measured by biolayer interferometry 5 days post transfection in μg/ml from 4 ml total. mAb = monoclonal antibody.

2.5. Virus infections

A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) and A/Hong Kong/01/1968ma (H3N2) were used to infect MDCK cells grown on glass bottom plates for one hour in serum-free Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 Media at a multiplicity of infection of (MOI) 1.0 with trypsin as previously described (Ranjan et al., 2010). After 24–48 h, infected cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 20 mins at 37 °C, and then stained overnight with (1:1000 dilution) of the anti-H3 monoclonal antibody described herein. The following day, cells were washed with 1× PBS, followed by staining with an anti-human IgG secondary antibody conjugated to FITC (1:10,000 dilution) for 2 h at room temperature. Cultures were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and mounted with ProLong gold antifade mountant (Thermo Fisher, Cat#P10144). Images were captured with the Zeiss LSM 710 inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and processed in Adobe Photoshop.

2.6. Microneutralization assay

Cell grown A/North Carolina/04/2016 (H3N2) was used to infect Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells for 2 h with 100 TCID50 in a microneutralization assay as previously described (Kim et al., 2009) with 50 μL of antibodies diluted from 50 μg/ml to 0.2 μg/ml and mixed with 50 μL of virus. The negative control is an IgG1 anti-HIV envelope (VRC-01) antibody, and positive control is a well-studied CR8020 (Ekiert et al., 2011) anti-HA stem antibody that has been shown to neutralize group 2 influenza viruses.

2.7. Protein gels

Transfection supernatants assessed with Agilent Protein 230 kits on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer following the manufacturer’s instructions. Coomassie stained SDS-page non-reduced gels were run with purified antibody and ladder (Precision Plus Protein™ Kaleidoscope™ Pre-stained Protein Standards from Bio-Rad; Cat# 1610375) showing typical banding patterns of pairing (Kirley and Norman, 2018). Images were taken with the GE Amersham™ Imager 680.

2.8. Biolayer interferometry

Biolayer interferometry (BLI) measurements were performed on an Octet® R8 machine with ProA biosensors (Cat# 18–5010) which detect IgG within a range of 0.25–2000 μg/ml. Data acquisition and analysis was done with Octet® BLI Discovery/Analysis Studio software.

B cell sequencing.

Paired heavy and light chains of B cell receptors (BCR) from isolated B cells bound to influenza hemagglutinin fluorescent probes were derived from influenza vaccinated individuals and recovered with chromium single cell sequencing VDJ reagent kits per 10× Genomics protocols in concert with the Illumina MiSeq system from single cells as previously described (Hanamsagar et al., 2020; Genomics, x. Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Reagent Kits with Feature Barcoding technology for Cell Surface Protein, 2019) (Fig. S3).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software where shown in the figures and text. Both paired and unpaired tests were performed where appropriate using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test or Spearman. The lack of statistical significance was noted as n.s. in the figures and the p-values were noted in the text.

3. Results

Here, we describe a simple cost- and time-efficient method to express antibodies from a single amplicon containing both heavy and light chain sequences generated from an overlapping PCR reaction of synthesized DNA fragments that could also be adapted in future directly to amplified products. The advantage of this method is that any antibody can be regenerated in vitro if the sequence is available in silico without having to synthesize the entire antibody sequence. By adding the constant elements of the linear cassette to the variable synthesized DNA fragments of the heavy and light chains, an overlapping PCR reaction can be used to create a transfectable linear cassette in a 2 h reaction.

As proof of concept, we generated an antibody expression cassette in a single plasmid consisting of a promoter, enhancer, leader sequence, signal peptide, light chain, Furin cleavage site, spacer, self-cleaving peptide, signal peptide, heavy chain, woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE), and poly(A) signal (Fig.1A). We compared the plasmid containing the expression cassette to a two-plasmid system (Fig. 1A) more commonly used because heavy and light chains derive from separate transcripts. Significantly more antibody (6.3-fold increase) expressed from the single construct compared to co-transfecting heavy and light chain plasmids from four independent experiments (Fig. 1B; p = 0.029). Given these results, this antibody expression cassette configuration was taken forward.

To bypass cloning steps and reduce the time and cost of antibody expression in vitro, we aimed to create a linear version of the single plasmid expression cassette where various antibody sequences could be swapped in and out, promptly transfected, and with potential for scaling up and adapting to synthesized DNA or PCR generated fragments. Amplification of overlapping portions targeting non-variable regions of the expression cassette from the single plasmid were carried out to generate DNA fragments to test various overlapping PCR conditions. The overlapping pieces that successfully produced a PCR amplicon (Table S1) were subsequently labelled as P1-P5 wherein P2 and P4 define the antibody clone and are added in a five-piece overlapping PCR reaction using a high-fidelity polymerase and one forward and one reverse primer (Fig. 2A–C). This reaction takes less than two hours and produces a transfectable DNA amplicon of ~3.9 kb (Fig. 2D) with no detectable PCR errors by Sanger sequencing as expected from the 2.17 × 10−7 error rate of the polymerase utilized (Mielinis et al., 2021). The overlapping nucleotides are of various sizes (18–88 bp) and stitch together five DNA fragments to create the full linear antibody expression cassette producing both heavy and light chains from one open reading frame (Fig. 3; Fig. S1).

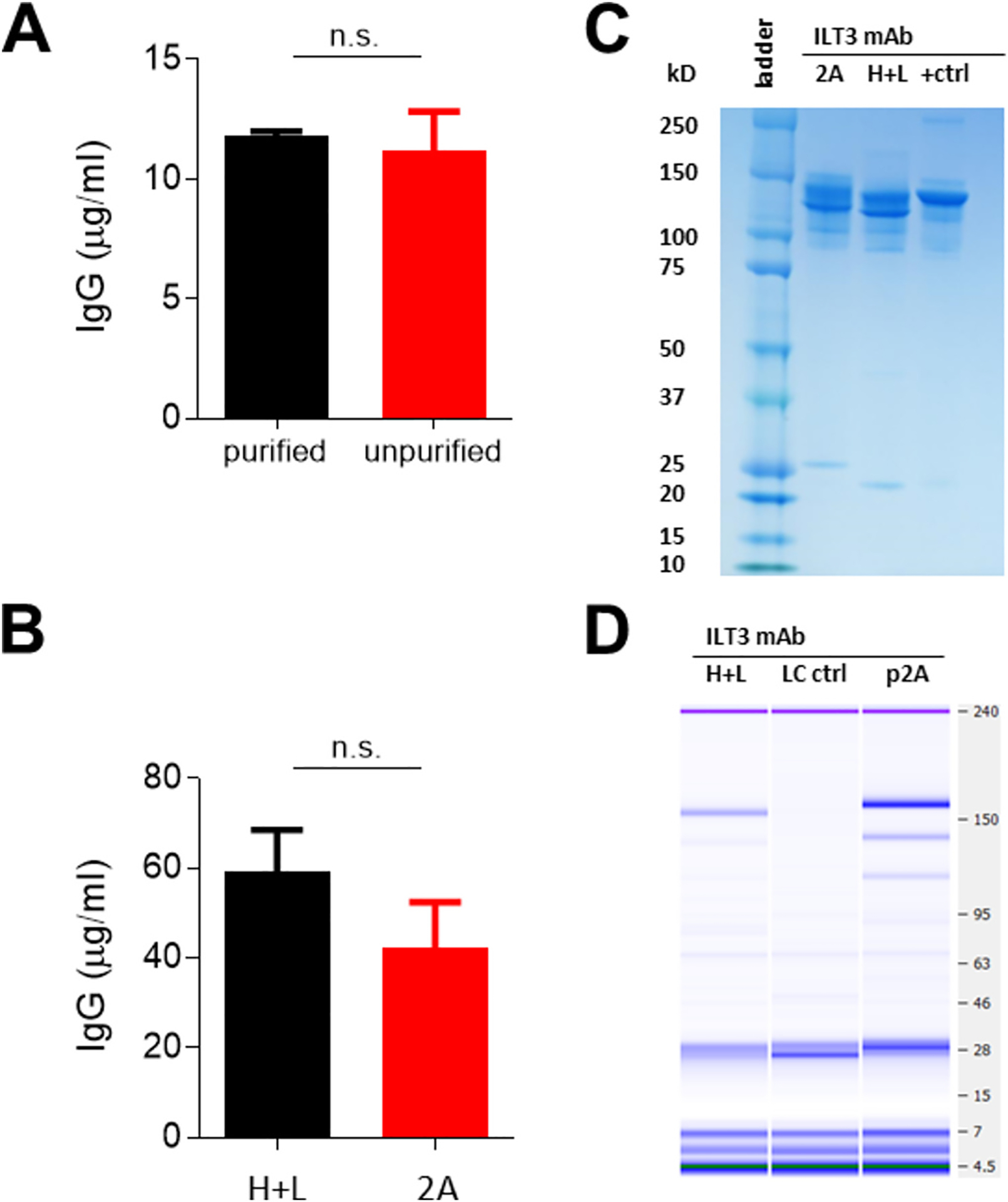

Amplified products resulting from the overlapping PCR reaction can be directly transfected or column purified by gel extraction or PCR clean-up methods. For instance, transfecting a 25 μL overlapping PCR reaction that is purified or unpurified yielded no difference in antibody levels produced under the same conditions (Fig. 4A; p = 0.50). Moreover, expressing the antibody from co-transfected heavy and light chain plasmids or linear product gave similar results with 2 μg transfections (Fig. 4B; p = 0.57), while heavy and light chain pairing was demonstrated in protein gels in both scenarios (Fig. 4C–D).

Fig. 4. Antibody expression from different transfection conditions.

a, Concentration of IgG from purified (black) and unpurified (red) overlapping PCR products. b, IgG for mAb ILT3 from co-transfected heavy and light chain plasmids (black; H + L) and linear expression cassette (red; 2 A) from 0.5 μg/ml transfections showing standard error of the mean for error bars. c, Coomassie stained protein gel (+ctrl = VRC01) of antibodies and d, bioanalyzer protein gel under non-reducing conditions (LC ctrl = light chain only supernatant) with transfection supernatants. Bands at the size of the paired antibody (~150 kD) gave 124 μg/ml (H + L) and 296 μg/ml (p2 A). mAb = monoclonal antibody. P-values are from the Mann-Whitney test.

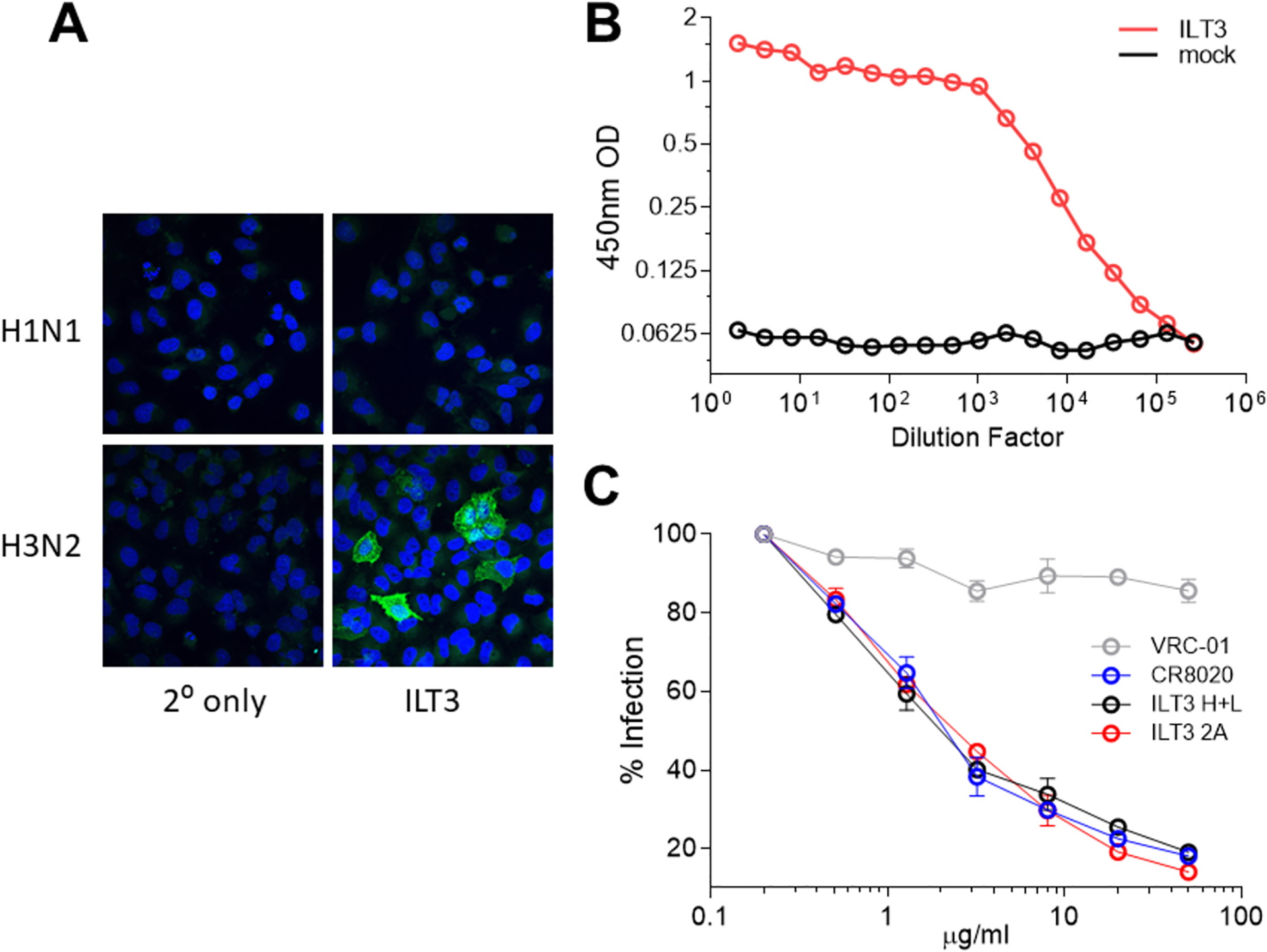

To demonstrate utility, an antibody expression cassette was made by synthesizing pieces P2 and P4 from a sequence available in silico. This sequence was a previously unknown antibody sequence from B cells derived from an influenza-vaccinated individual whose Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells had been sorted for B cell receptor hemagglutinin specificity and single cell sequenced with 10× Chromium™ (Hanamsagar et al., 2020; Genomics, x. Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Reagent Kits with Feature Barcoding technology for Cell Surface Protein, 2019) (Fig. S3). After amplifying and transfecting the linear expression cassette, the mAb containing supernatant bound to H3N2 infected cells by fluorescence microscopy but not H1N1 (Fig. 5A), and measurably bound to a group 2 hemagglutinin (H3 HA) out to a dilution of ~1 in 105 in an ELISA (Fig. 5B) at 1.08 ng/ml. Additionally, the purified antibody from the expression cassette functionally neutralized an H3N2 virus in vitro in MDCK cells to levels similar to a previously described (Ekiert et al., 2011) group 2 influenza-specific neutralizing antibody (Fig. 5C). Thus, the antibody expression cassette produced a functional neutralizing antibody (named here as ILT3) that bound to its epitope on purified hemagglutinin protein and on infected cells.

Fig. 5. Anti-influenza antibody expression and binding to influenza hemagglutinin.

a, Immunofluorescence assay showing ILT3 binding to H1N1 or H3N2 infected MDCK cells in vitro (DAPI, blue; HA, green). b, Binding to H3N2 HA by ILT3 anti-influenza mAb containing supernatant (red) from cells transfected with the linear antibody expression cassette put together by overlapping PCR and mock (black). c, Microneutralization assay using an H3N2 virus and the following mAbs: positive control CR8020 (+ ctrl; blue), negative control VRC-01 (− ctrl; grey), ILT3 from heavy and light chains (H + L; black) or expression cassette (2 A; red). Significance determined by Mann-Whitney test.

The variability of antibody sequences can present a challenge to antibody generation. To examine the robustness of this method to handle sequence diversity, 15 linear mAb cassettes of unique sequences were generated concurrently from memory B cells as previously described for ILT3 (Fig. S3), though any sequences available in silico could be used. All 15 amplified antibody expression cassettes produced transfectable amplicons (Fig. 6A) which were simultaneously transfected, resulting in sufficient amounts of mAb for downstream applications after 5 days in 2 ml of culture (Fig. 6B; avg. = 47 μg/ml; range 14–98 μg/ml).

4. Discussion

Described herein is a simple, efficient, and flexible method for human mAb antibody expression. Required to create the cassette is a PCR machine, PCR reagents, and synthesized DNA fragments, with the potential to accommodate PCR amplified fragments. The overlapping PCR reaction takes approximately 2 h and generates enough product in one or two 50 μL reactions to be transfected either directly or post-PCR clean-up or gel extraction. This study adds to the various methods for antibody cloning and production described in the background section. The method could be adapted for more rapid antibody production in many different antibody workflows that currently use plasmids for cloning, transformation, plasmid-prep, and transformation.

There are a few relevant limitations to this study. First, PCR amplified products derived directly from heavy and light chain Ig mRNA or DNA was not used. Although there is no reason this could not be accomplished in future iterations, it was beyond the scope of this manuscript. Second, this study was limited to IgG1 subtype antibodies and two light chains, and therefore did not include IgA, IgE, IgD, or IgM isotypes. Nonetheless various isotypes could be adapted for this method. Finally, the increased titer of antibodies from single versus double plasmid transfections, could be due to the sequence of the construct, or from the increased combinations of heavy and light chain DNA per microgram of plasmid. Thus, we were unable to compare these constructs directly due to the excess light chain preferred in the two-plasmid system, although this finding is not directly relevant to the linear product except as a proof of concept for the linear sequence.

This method can be applied to any isotype as a medium-throughput method, with high-throughput potential with minor adjustments. This is a simple and useful alternative to synthesizing a full antibody sequence, while reducing the time, reagents, and expertise needed for cloning and plasmid preparation. In future, amplifying paired immunoglobulin mRNA or DNA, and coupling the cloning PCR reaction described here has the potential to change how fast antibodies can be generated in any lab already suited for molecular biology and cell culture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jason Wilson, Priya Ranjan, Shiva Gangappa and Zhu Guo for helpful discussions. Weiping Cao, Sean Ray, Caitlin D. Bohannon, Suresh Sharma and Zhunan Li for technical assistance. Mili Sheth, Dhwani Batra, and Jan Pohl for sequencing assistance. Paul Carney, Jessie Chang, and James Stevens for recombinant HA. This work was supported by a Public Health Service Grant (HL151498) awarded to Paul R. Knight from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, NIH.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Declarations

All human antibody cloning, expression and affinity measurements experiments were carried out at BSL2 containment.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare to have no financial and non-financial competing interests.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2024.113768.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Almagro JC, Mellado-Sanchez G, Pedraza-Escalona M, Perez-Tapia SM, 2022. Evolution of anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic antibodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci 23. 10.3390/ijms23179763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrebaeck CA, 2000. Antibodies in diagnostics - from immunoassays to protein chips. Immunol. Today 21, 379–382. 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briney B, Inderbitzin A, Joyce C, Burton DR, 2019. Commonality despite exceptional diversity in the baseline human antibody repertoire. Nature 566, 393–397. 10.1038/s41586-019-0879-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chng J, et al. , 2015. Cleavage efficient 2A peptides for high level monoclonal antibody expression in CHO cells. MAbs 7, 403–412. 10.1080/19420862.2015.1008351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D, Purcell LA, Snell G, Veesler D, 2021. Tackling COVID-19 with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Cell 184, 3086–3108. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty PS, Olsen MJ, Iverson BL, Georgiou G, 1999. Development of an optimized expression system for the screening of antibody libraries displayed on the Escherichia coli surface. Protein Eng. 12, 613–621. 10.1093/protein/12.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva NS, Klein U, 2015. Dynamics of B cells in germinal centres. Nat. Rev. Immunol 15, 137–148. 10.1038/nri3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekiert DC, et al. , 2011. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza a viruses. Science 333, 843–850. 10.1126/science.1204839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genomics x. Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Reagent Kits with Feature Barcoding technology for Cell Surface Protein. https://assets.ctfassets.net/an68im79xiti/4MHAUJ5dDJ4Jhsu0zqedmJ/2a94883302932950be607555bd986664/CG000186_ChromiumSingleCellV_D_J_ReagentKit_FeatureBarcodingtechnology_RevD.pdf, 2019.

- Gieselmann L, et al. , 2021. Effective high-throughput isolation of fully human antibodies targeting infectious pathogens. Nat. Protoc 16, 3639–3671. 10.1038/s41596-021-00554-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchuk IM, et al. , 2021. Human antibody recognition of H7N9 influenza virus HA following natural infection. JCI Insight 6. 10.1172/jci.insight.152403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman RD, 2000. Antibodies: indispensable tools for biomedical research. Trends Biochem. Sci 25, 593–595. 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01725-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanamsagar R, et al. , 2020. An optimized workflow for single-cell transcriptomics and repertoire profiling of purified lymphocytes from clinical samples. Sci. Rep 10, 2219. 10.1038/s41598-020-58939-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, et al. , 2013. Isolation of human monoclonal antibodies from peripheral blood B cells. Nat. Protoc 8, 1907–1915. 10.1038/nprot.2013.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Skountzou I, Compans R, Jacob J, 2009. Original antigenic sin responses to influenza viruses. J. Immunol 183, 3294–3301. 10.4049/jimmunol.0900398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL, Norman AB, 2018. Unfolding of IgG domains detected by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 503, 944–949. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler G, Milstein C, 1975. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 256, 495–497. 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HX, et al. , 2009. High-throughput isolation of immunoglobulin genes from single human B cells and expression as monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. Methods 158, 171–179. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, et al. , 2017. Systematic comparison of 2A peptides for cloning multi-genes in a polycistronic vector. Sci. Rep 7, 2193. 10.1038/s41598-017-02460-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu RM, et al. , 2020. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J. Biomed. Sci 27, 1. 10.1186/s12929-019-0592-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor Y, Van Blarcom T, Mabry R, Iverson BL, Georgiou G, 2007. Isolation of engineered, full-length antibodies from libraries expressed in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol 25, 563–565. 10.1038/nbt1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty J, Griffiths AD, Winter G, Chiswell DJ, 1990. Phage antibodies: filamentous phage displaying antibody variable domains. Nature 348, 552–554. 10.1038/348552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielinis P, et al. , 2021. MuA-based molecular indexing for rare mutation detection by next-generation sequencing. J. Mol. Biol 433, 167209. 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SA, 2010. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol 17, 1055–1065. 10.1128/CVI.00131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SA, 2020. Updates on immunologic correlates of vaccine-induced protection. Vaccine 38, 2250–2257. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan P, et al. , 2010. 5’PPP-RNA induced RIG-I activation inhibits drug-resistant avian H5N1 as well as 1918 and 2009 pandemic influenza virus replication. Virol. J 7, 102. 10.1186/1743-422X-7-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinitz M, Klein G, Koskimies S, Makel O, 1977. EB virus-induced B lymphocyte cell lines producing specific antibody. Nature 269, 420–422. 10.1038/269420a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiller T, et al. , 2008. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J. Immunol. Methods 329, 112–124. 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonegawa S, 1983. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature 302, 575–581. 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traggiai E, et al. , 2004. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat. Med 10, 871–875. 10.1038/nm1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Boehmer L, et al. , 2016. Sequencing and cloning of antigen-specific antibodies from mouse memory B cells. Nat. Protoc 11, 1908–1923. 10.1038/nprot.2016.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, et al. , 2018. Functional interrogation and mining of natively paired human VH: VL antibody repertoires. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 152–155. 10.1038/nbt.4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M, Kurosawa N, Isobe M, 2011. Target-selective joint polymerase chain reaction: a robust and rapid method for high-throughput production of recombinant monoclonal antibodies from single cells. BMC Biotechnol. 11, 75. 10.1186/1472-6750-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, et al. , 2020. Single-cell sorting of HBsAg-binding memory B cells from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and antibody cloning. STAR Protoc. 1, 100129. 10.1016/j.xpro.2020.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.