Abstract

Background

Uterine rupture is a rare but severe obstetric complication that poses significant risks to maternal and fetal health. Understanding the lived experiences of individuals who have undergone uterine rupture is crucial for improving care and support for those affected by this condition. This qualitative phenomenological study aimed to explore the experiences of individuals who have experienced uterine rupture.

Method

The study employed a qualitative phenomenological approach, conducting 12 in-depth interviews and four key informant interviews with individuals who had experienced uterine rupture. Data analysis was conducted thematically using Atlas ti software to identify patterns and themes within the participants’ narratives.

Results

The analysis of the interviews highlighted six key themes: experience during diagnosis and initial symptoms, perceived predisposing factors of uterine rupture, challenges faced by individuals with uterine rupture, impacts on their lives, and coping and resilience strategies. The findings revealed that women often failed to recognise the initial symptoms of uterine rupture due to a lack of preparation, a preference for home deliveries, husband refusal, and a general lack of awareness. This delay in seeking care resulted in severe consequences, including the loss of their babies, infertility, fistula, psychological trauma, and disruptions to daily life and relationships. To cope, many women resorted to accepting their situation, isolating themselves, and using traditional healing techniques.

Conclusions

This study’s findings provide valuable insights into the complex and multifaceted nature of uterine rupture, shedding light on the experiences of those affected by this condition. To address the challenges, it is essential to enhance awareness and education through community education programs and comprehensive antenatal classes. Additionally, improving access to healthcare by strengthening health infrastructure and deploying mobile health clinics can ensure better prenatal care. Furthermore, encouraging hospital deliveries through incentives and the support of community health workers can reduce risks. Providing psychological counselling and establishing support groups can help affected women cope with the consequences. Moreover, engaging men in maternal health through educational programs and involving them in antenatal care can foster better support. Finally, promoting safe traditional practices by integrating traditional healers and respecting cultural sensitivities can increase acceptance and adherence.

Keywords: Uterine rupture, Delays, Coping, Tertiary hospital, Phenomenology, Ethiopia

Background

Uterine rupture is a severe obstetric complication that occurs when the muscular wall of the uterus tears during pregnancy or childbirth [1]. It can lead to life-threatening maternal and fetal outcomes if not promptly diagnosed and managed [1]. The lived experiences of women with uterine rupture who were managed in specialised hospitals are multi-faceted and deeply influenced by a range of factors, including the clinical severity of the condition, the quality of obstetric care received, the sociocultural context in which they live, and the support systems available to them [2]. Uterine rupture is a severe but rare obstetric complication that can have profound physical, emotional, and social implications for affected women [3]. When managed in specialised hospitals, these women’s experiences are shaped by the unique dynamics of the healthcare setting, the interactions with healthcare providers, and the overall quality of care provided [4, 5].

The journey of women with uterine rupture in specialised hospitals encompasses not only the clinical aspects of their condition but also the psychosocial impact it has on their lives [6, 7]. Factors such as access to healthcare services, cultural beliefs and practices, and the availability of support networks play a crucial role in shaping their experiences [8–10]. Understanding these lived experiences is essential for identifying areas for improvement in obstetric care, addressing the holistic needs of affected women, and ultimately enhancing maternal health outcomes [2]. By exploring the nuanced aspects of their experiences, we can gain valuable insights that can inform targeted interventions and support systems to better meet the needs of women who have undergone this traumatic obstetric event.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the lived experiences of women who survived uterine rupture and managed in Nekemte Specialized Hospital. Studying the lived experiences of women with uterine rupture in specialised hospitals is crucial for improving clinical care, enhancing patient-centred approaches, informing policy and practice, addressing sociocultural factors, fostering empathy, and empowering patient advocacy. This knowledge can ultimately contribute to better maternal health outcomes and a more supportive healthcare environment for affected women.

Methods

Study setting

The primary objective of this study was to explore the lived experiences of women with uterine rupture managed at Nekemte Specialized Hospital between January 2014 and December 2022. Researchers conducted interviews with these women from March to August 2023. Nekemte Specialized Hospital, located 331 km west of Addis Ababa, is a long-standing institution offering a wide range of medical services and has seen 37,748 deliveries and 510 uterine rupture cases during the study period.

Study design

A phenomenological qualitative study design was applied to explore the lived experiences of women who survived uterine rupture and managed in Nekemte Specialized Hospital [11, 12]. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with women who had experienced this obstetric complication. The study delved into the emotional, physical, and social aspects of their experiences. By capturing these firsthand accounts, the research contributes to a deeper understanding of uterine rupture and its impact on women’s lives.

Study participants

The study participants were women who survived uterine rupture and were managed in the Hospital. It focused on women who had participated in a project related to uterine rupture between January 2014 and December 2022. For this qualitative study, researchers retrospectively selected participants from a list. Interviews were conducted with these women March and August 2023. Additionally, Midwives, gynecologists, obstetricians, and integrated emergency surgical officers were incorporated into the study.

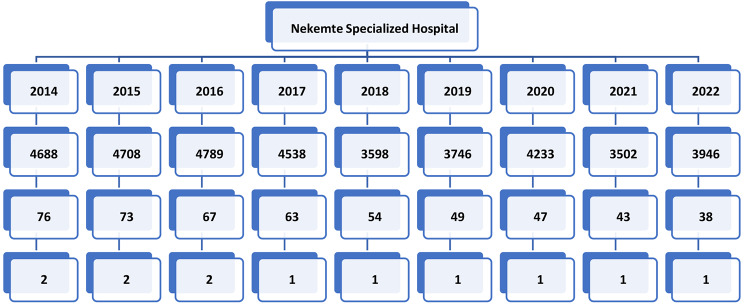

To select the participants, we traced the number of deliveries per year and the number of uterine ruptures per year from the registers for each year. Then, we selected the 12 women from the list of uterine ruptures from 2014 to 2022 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection procedure of the mothers (interviewee)

Sample size and sampling technique

The study used data saturation to determine the number of interviews [13, 14], conducting twelve in-depth interviews (IDIs) with women who experienced uterine rupture to understand their experiences and four key informant interviews (KIIs) with health professionals to gain insights into the challenges of managing uterine ruptures. Participants were selected through criteria-based purposeful sampling [15, 16], with key informants chosen based on seniority, position, and active service during the project period, and women selected based on specific criteria such as hospital stay duration and medical history. The interviews aimed to gather perceptions of care, emotional responses, and suggestions for improvement from patients and healthcare providers.

Data collection

To explore the lived experiences of women who survived uterine rupture and managed in the Hospital, different data-gathering methods and sources were applied. Well-versed written consent was taken from each study participant. Written permission was approved to record the conversation. To uphold the seclusion, anonymity, and confidentiality of data, we explained to each respondent that their identity and the evidence they would provide would be secret. It was further clarified to the participants that only the researchers directly involved with this study would access it. This explanation helped to create an environment where women felt safe discussing personal experiences. Confidentiality was maintained after the data was collected by de-identifying the field notes, transcripts, audio recordings, and subsequent publications. In this article, the researcher used generic terms such as ‘study participants’ and ‘female workers’ instead of their names. Despite steps taken to ensure that participants felt safe and comfortable sharing information with researchers, some participants were still reluctant to reveal their experiences. It was explained that no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers existed in that location. The study participants had the right to terminate the interview/withdraw from the subject field at any time. Privacy and confidentiality were ensured in each interview. Moreover, by conducting IDIs away from the hospital, participants were assured that they could freely discuss the issues without fear of such conversations being tracked by their healthcare providers. The In-depth interview guide included broad, open-ended questions regarding experiences, emotions, challenges, and interactions with healthcare providers while managing uterine rupture (Table 1). The same but relatively shorter questions were used in key informant interviews to understand the phenomenon from a provider’s perspective. The key informants were chosen for their capacity to assist the researcher in comprehending cultural patterns, frequently offering background information that is otherwise inaccessible, implicit, or difficult to uncover through document reviews or other incomplete sources [17–20]. The guides were adopted from different studies and modified to the country context in some conditions [2, 21]. Similarly, it was enriched during the interview process. All In-depth interviews were conducted in Afan Oromo, a local language, and at convenient places for the women (organised by the principal investigator). Key informant interviews were conducted in the private offices of the health Nekemte specialised hospital—one MSc. maternity and reproductive health professional with qualitative data collection experience involved in data collection. The principal investigator has also been involved in four KIIs. All the KIIs and IDIs were audio-recorded, and notes were taken to supplement the audio recording with participants’ permission.

Table 1.

Interview guide on lived experiences of women with uterine rupture

| Number | Issue explored | Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Personal characteristics of the interviewee | Could you tell me all about yourself? |

| 2 | History of pregnancy, childbirth, and circumstances in which uterine rupture injury occurred | Could you tell me about the circumstances of your pregnancy, childbirth, and what happened after that? |

| 3 | Effect of uterine rupture on health in totality (physical, psychological, and social wellbeing). |

Please tell me about your everyday experiences with a history of uterine rupture. How did she feel about her current health situation? Probe physical symptoms, social relations, socioeconomic situation, and psychological/emotional well-being. |

| 4 | Impact of uterine rupture on social relationships and livelihood | Please tell me about your social situation since childbirth (probe for marital relations and social network). |

| 5 | Experiences of living as a survivor of uterine rupture |

Tell me about your everyday experiences as a woman with this problem. What challenges did she face due to her condition regarding work, your relationship with your spouse, friends, and family? |

| 6 | Coping as a survivor of uterine rupture | How have you been able to cope with the condition? What health problems have you experienced since childbirth? |

| 7. | Characteristics of participants | Participant’s identifier number |

| Age in year | ||

| Marital status | ||

| Education level | ||

| Occupation | ||

| Ethical consent verbal (V) / written(W) |

The KII and in-depth interviews took around 30 min. Participants received tea, coffee, water, soft drinks, and transportation cost reimbursement.

Data analysis

An inductive analytic approach was used to analyse field notes and transcripts iteratively [22, 23]. All recorded KIIs, in-depth interviews, and field notes were transcribed verbatim into Afan Oromo (the local language) and translated into English. The principal investigator and selected experienced research assistants prepared the transcripts. Some transcripts and audio files were cross-checked to confirm the accuracy and consistency of files before coding. The principal investigator read sample transcripts prepared by research assistants to check consistency. Data analysis was conducted using Braun and Clark’s (2006) thematic analysis approach [24]. To become familiar with the data and generate meaningful codes, the principal and research assistants read the descriptive information repeatedly. The analysis methodology relies on data-driven codes generated through an open coding process involving minor codes’ classification. The primary investigator and co-investigators separately coded a set of transcripts from each interview category, and all authors agreed on a list of codes to ensure the validity of the coding. The computer software Atlas-ti, version 7, was used to categorise small codes using open coding techniques. The principal and co-authors independently coded transcripts from each interview category to ensure the reliability of the newly emerging codes. Then, the small codes were grouped to generate main themes, which were debated and decided upon. Finally, the generated themes become the categories for the analysis [25]. The framework was developed based on these central themes.

Trustworthiness

Different activities were considered to ensure the study’s credibility, dependability, transferability, and conformability. The researchers edited and modified the IDI and KII guides based on a pre-test finding. The credibility of the conclusions was increased by team triangulation of the data from women and health professionals. The risk of researchers’ reactivity was managed by normalizing the research process during the KIIs and IDIs by explaining the purpose and goals of the study to assure participants that their honest and authentic responses are valued, regardless of whether they align with the researchers’ expectations. Establishing rapport and trust has also been used to build a trusting relationship with participants to create a comfortable environment for sharing their experiences and perspectives. Emphasis was given to confidentiality and assurance to participants that their responses would be kept anonymous. A non-intrusive and unobtrusive approach training was provided to data collectors to minimise the observer effect used by data collectors to data collection.

Ethical considerations

Based on the approval from the Wallaga University Institutional Research Ethics Review Committee, the Jimma University Institute of Health Science Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRB) granted permission to use the data generated for the massive research from January 2014 GC to December 2022 GC. The ethical issue was approved by the IRB of Jimma University (Ref No JUIH/IRB/587/23) and the Institutional Review Committee of Wallaga University (Ref No. CMHS/21/2014 GC). So, the hospital’s management granted us access to the patient’s medical records. Using coding, all data privacy and confidentiality were maintained during the study. The World Health Organization’s ethical and safety recommendations for exploring sensitive topics were observed.

Results

Participants characteristics

Sixteen participants (12 Women and four key informants) participated in this study. The average length of record for each IDIs was 40 min, and 45 min for KIIs. The women’s age ranged from 18 to 39 years. Among the interviewees, four women developed urinary fistula, two of the women were paralysed, three of them officially separated from their husbands, and all of them stopped their usual work (Table 2). The key informants’ ages ranged from 37 to 39 years, and they were gynecologists and obstetricians, emergency surgeons, and midwives (Table 3).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic profile of women whose uterus was ruptured and managed in Nekemte specialized hospital and involved in the in-depth interviews, January to August 2022

| Participant code | Age (yrs.) | Parity | Educational level | Marital status | Occupation | Infant outcome | Ux Status | LHS Day |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous | current | ||||||||

| 002 | 28 | 3 | Grade 4 | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | **Removed | 16 |

| 003 | 34 | 5 | Illiterate | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | *Removed | 23 |

| 004 | 26 | 3 | Grade 3 | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | Removed | 14 |

| 005 | 39 | 5 | Grade 4 | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | Removed | 14 |

| 006 | 38 | 7 | Illiterate | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | *Removed | 30 |

| 007 | 24 | 2 | Grade 5 | Married | Married | Housewife | Died | Removed | 14 |

| 008 | 32 | 5 | Grade 11 | Married | Married | Housewife | Died | *Removed | 19 |

| 009 | 25 | 1 | Grade 11 | Married | Divorced | Farmer | Died | **Removed | 21 |

| 010 | 30 | 4 | Grade 11 | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | Removed | 10 |

| 011 | 36 | 5 | Grade 2 | Married | Married | Farmer | Died | Removed | 14 |

| 012 | 28 | 2 | Grade 6 | Married | Divorced | Merchant | Died | Removed | 14 |

| 013 | 31 | 4 | Grade 2 | Married | Divorced | Farmer | Died | *Removed | 21 |

*=Developed urine incontinence [Fistula], ** = Developed Foot Drop (Paralysis), LHS = length of hospital stays in days

Table 3.

Sociodemographic profile of key informants in Nekemte Specialized Hospital and involved in the in-depth interviews, January to August 2022

| Code | Age | Sex | Profession | Educational level | Experience | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E002 | 37 | Female | Midwife | 1st degree | 16 years | Married |

| E003 | 38 | Male | Integrated Emergency Surgical Officer | 2nd degree | Five years | Married |

| E004 | 39 | Male | Gynecologist & obstetrician | Specialist | Nine years | married |

| E005 | 38 | Male | Midwife | 1st degree | 15 years | Married |

Six themes and fifteen sub-themes have been generated in this study. The identified themes include (1) Experience during diagnosis & initial symptoms, (2) the perceived predisposing factors of uterine rupture, (3) challenges, (4) impacts, and (5) coping and resilience.

Diagnosis and initial symptoms

Due to the perception that their labour process would be as smooth as usual, most women who experienced uterine rupture stayed at home for 2 to 3 days before they went to the health centre:

I delivered all the previous children at home and waited the same for the current pregnancy. I was in labour for four days. During these four days, I tried many things like a drink, ‘Tella,’ ‘Telba,’ and an abdominal massage by local traditional birth attendants to facilitate the delivery. However, the bleeding started on the fourth day. Then, I went to the health centre on the fifth day (a 30-year-old Para 4 mother).

Key informants added:

Up on their arrival, there was severe abdominal pain upon palpation, easy access to the fetal part, bleeding, abdominal distension, and swelling around the genital area. There was also prolonged membrane rupture (over 8 h), which led to fever and increased infection risk …(a 38-year-old male midwife with 15 years of experience).

The participants mentioned that combining these symptoms with a lack of emergency preparation creates a sense of urgency and fear, prompting them to seek immediate medical attention.

…, it was difficult labour. I was in labour for two days, and there was fluid discharge from my genital organ. My husband was not in good health and called my mother to take me to the health post. Then she came and called the neighbours. They took me to the health post by carrying me. The fluid was lost, and my body became dried. From the health post, I referred to the health centre. When we arrived at the health centre, they shouted at me and told me that the baby was not alive. They referred me to the hospital. But there was an ambulance, and we had no money. We asked relatives and went to the hospital on the third day evening. The operation was done to remove the ruptured uterus, and the baby died. We stayed for two weeks and took medication and different medications. After the operation, my health status changed. I can’t control my urine, and I fear, even for my children and husband, due to urine incontinence… (A 25-year-old, para 2 mother).

Women also exhibited signs of shock, such as dizziness, lightheadedness, rapid heartbeat, and pallor.

Not only was there copious vaginal bleeding, but I was dizzy, and the baby’s movement and pressing down agony also stopped. When I first got to the hospital, I didn’t know who I was. I had an IV line in my hands, and the operation was completed when I realised who I was. I believe I’ve been given blood (34 years old, Para 5 mother).

A key informant added:

They stayed in labour for a long duration at home and health centres. Due to prolonged labour, they came with signs and symptoms of shock; they were weak and felt pain when they arrived at the hospital (KII, A 39-year-old male gynaecologist and obstetrician with nine years of experience).

Women also mentioned that the initial experience of symptoms of uterine rupture was characterised by confusion, disbelief, and overwhelming anxiety. The sudden onset of intense pain and bleeding disrupts their sense of normalcy and triggers a sense of impending danger.

Immediately upon arrival at the health centre, Health professionals told me it was beyond their capacity and referred me to the hospital. Unfortunately, there was no ambulance, and we came by truck. On the way to the hospital, the baby’s movement ceased, and the feeling of pushing was also stopped. I saw a little blood. Immediately upon arrival at the hospital, health professionals told me that my uterus had ruptured and my unborn baby had died. All these conditions led me to confusion, disbelief of my situation, and overwhelmed by excess anxiety (A 34-year-old, Para 5 mother).

A key informant added:

They remain in labour for extended periods at home and the health centre. When they got to the hospital, they were weak and in pain, had excess anxiety, disbelief of their situation and our services, and were confused by the things we told them (A 39-year-old male gynaecologist and obstetrician with nine years of experience).

Perceived predisposing factors

Women raised concerns about harmful traditional practices such as uterine massage and the use of flax seeds (Telba-Amharic), which were identified as predisposing factors for uterine ruptures.

… “Telba’[flax seed] was given to me, and my abdomen was massaged to facilitate the birth process. In between, the labour stopped, and I was exhausted. Then, my family and neighbours took me to the health centre. From the health centre, I was referred to the hospital. Bleeding starts on the fourth day, and I can’t take any food. So, they told me that the uterus was ruptured and the baby had died (36 years old para 5 mother).

Key informants also reported that many risk variables, such as prior cesarean sections:

Uterine rupture can happen to women who have previously undergone one or more surgical deliveries. For instance, five minutes into our follow-up, a mother who had previously undergone CS and chosen a vaginal birth began showing symptoms of impending uterine rupture. Fortunately, the infant survived since the rupture was not entirely complete. She was underfollowed for a labour trial and had only ever had one procedure. Her uterus ruptured a few minutes later (38-year-old male BSc midwife with 15 years’ experience).

Another key informant, a dedicated obstetrician, shed light on the dangers of prolonged labour:

…, this prolonged labour can result in uterine rupture (A 39-year-old male gynaecologist and obstetrician with nine years of experience).

Another Midwife discussed the risks associated with the misuse of oxytocin during labour induction or augmentation:

… sometimes it may happen due to the giving of oxytocin if it is not followed appropriately ….(A 37-year-old female midwife with 16 years of experience).

A key informant also highlighted the vulnerability of women with multiple pregnancies to uterine rupture, lack of ANC follow-ups, and removal of tumours:

The majority of the women gave birth to more than five children, had no ANC follow-up, and had a history of previous cesarean section and removal of tumours experiencing uterine rupture (A 38-year-old male IESO, Five years of experience).

Furthermore, the journey of women in the specialised hospital leading up to the diagnosis of uterine rupture was marked by a series of challenges and delays in seeking timely medical care:

… I was in labour for four days. During these four days, I tried many things like a drink of ‘Tella’ or ‘Telba [flaxed seed],’ and a massage was done for me by local traditional birth attendants to facilitate the delivery. However, the bleeding started on the fourth day and brought me to the health centre on the 5th day (a 30-year-old Para 4 mother).

Reasons for delays

According to the interviewee and key informants’ reports, women’s delay in seeking care stemmed from a lack of awareness or education about the warning signs of pregnancy complications and husband refusal. Many women did not recognise the urgency of their symptoms, or their husbands hesitated to seek medical attention due to a lack of awareness and their preference for home delivery:

We didn’t come to health facilities as labour started. Instead, we stayed at home. This is due to a lack of awareness, money, transportation, and health facilities’ unavailability, as well as my husband’s refusal due to a lack of understanding (38-year-old para four mother).

Another participant added:

… my husband also refused to take me to a health facility. However, I was in labour for a long duration, and finally, my family and neighbours took me to health post (38-year-old, illiterate, para 7 mother).

A key informant added that the women were delayed due to their history of smooth home delivery, lack of ANC follow-up, and fear of fear of cesarean section.

The majority had no ANC follow-up and had a history of home delivering for their three or more children. So, they prefer to give birth at home and come to a health facility when it is complicated (A 39-year-old male gynaecologist and obstetrician with nine years of experience).

In addition, their delay in reaching care highlights the geographical and infrastructural barriers that impede access to healthcare services. Women living in remote areas mentioned the challenges in getting a healthcare facility equipped to manage obstetric emergencies like uterine rupture. Poor road conditions, limited transportation options, and financial constraints/lack of emergency preparedness and readiness also contributed to this delay:

Most of the time, labor starts at night, and it is inconvenient for the ambulance to take it at night. The road is also not good for the ambulance (a 26-year-old para-three mother).

A key informant added:

Most women who develop uterine rupture were those women who came from remote areas. Because labor started at night or while the husband was at work, it was not easy to carry and take to the health facility. There was also no birth preparation, and even after arrival, they could not afford to buy medication (37-year-old female midwife with 16 years of experience).

Participants also claim that the time it took to receive care highlighted the shortcomings in healthcare delivery systems, which could jeopardize prompt and efficient medical care. The congested hospitals, which led to long queues, contributed to the delays in giving the critical treatment they needed.

…Upon arrival at the hospital with a referral slip from the health center, the personnel instructed us to issue the registration card. The enormous lines outside the card rooms meant that it took a while to receive a card, which caused the pushing down pain to decline and bleeding to begin. My baby was weak and had a ruptured uterus when they checked it. They then informed me that I needed surgery. Following surgery, I was told that the baby had been moved to a different room, but two days later, I was informed that my baby had died (32 years old para 5 mother).

Perceptions of care and support

The experiences of women who have survived a uterine rupture were deeply intertwined with their perceptions of care and support during this harrowing ordeal. These women often recount a rollercoaster of emotions ranging from fear and vulnerability to gratitude and resilience:

I had my previous baby in the hospital via surgery, and they advised me to have my second child there as well. But I’m afraid of the surgery, and my spouse won’t take me to the hospital. After protracted labour, my family, neighbours, and I were finally taken to the hospital (25 years old para one mother).

For many of these women, the care and support they received from healthcare providers were pivotal in their survival and recovery. They speak of the medical team’s compassion, expertise, and dedication, who worked tirelessly to save their lives and ensure their well-being:

I was promptly referred to the health centre by the health post. Upon arrival, my labour and the flow of vaginal fluid were abruptly halted. The medical staff at the health centre quickly assessed my condition and discovered that I had a ruptured uterus and that my baby had tragically passed away. During the chaos, the staff, though stressed, provided me with all the necessary care and urgently instructed me to go to the hospital for further treatment. When we arrived at the hospital, the staff were very professional and compassionate. They explained the severity of my condition and the need for immediate surgery. They provided detailed information, offered advice, and had us sign the necessary consent forms. The surgery was performed promptly. After the procedure, the doctors informed my husband and me that, due to the removal of my uterus, I would no longer be able to conceive. This news was devastating, especially at the age of 25, as a mother of one. The entire experience was overwhelming, but the medical staff’s support and care were crucial during this difficult time (25 years old para one mother).

Another participant added

When I first got to the hospital, I didn’t know who I was. I had an IV line inserted in my hands when I first realised who I was. I believe the blood was donated for me (26-year-old Para 3 mother).

Moreover, the emotional support provided by family members, friends, and community members played a crucial role in helping these women navigate the aftermath of a uterine rupture. Their support network’s love, empathy, and practical assistance were lifelines during immense stress and vulnerability. Many women express deep appreciation for the unwavering presence of their loved ones, highlighting the power of human connection in times of crisis.

I figured I could give birth at home because it was my sixth pregnancy. I thus spent two days at home in labour. I was givenTalba[flax seed] to help in the birthing process. I was pretty exhausted in between when the labour stopped. In all the above processes, my family and neighbours were with me. They then drove me to the hospital (36 years old para 5 mother).

Level of support

The patients and medical personnel communicated straightforwardly, enlighteningly, and kindly. The healthcare professionals reassured the women and their families of any doubts or concerns they might have had by explaining the situation clearly and understandably. The medical staff’s empathy for these women was clear from their words and actions.

When the labour began, I went to the nearest health centre, as usual, to give birth on Monday. I spent Thursday through Friday at the health centre. On Thursday, they gave me glucose and referred me to the hospital. They instructed me to get to the hospital right away.…. They then sent me to the hospital through an ambulance. As soon as I got to the hospital, they informed me that the fetus had died, my uterus had burst, and I needed to have surgery and have the uterus removed right away. I signed the consent form, and the procedure was completed for me. During my two weeks in the hospital, I was unable to go to the bathroom and use a catheter. Then they informed my husband and me that I would not be able to conceive in the future (35 years old para 5 mother).

Another mother Added:

The bleeding began on day four, and on day five, I was sent to the health clinic. When we got to the health centre, they put me on glucose, told me that labour had halted, and referred me to the hospital. A laboratory test was performed at the hospital, and as soon as they informed me that the baby had died and the uterus had ruptured, an operation was also performed (30 years para 4 mother).

Challenges

According to participants, once uterine rupture occurs and the women are managed, a new set of challenges appears:

It has been eight months since the surgery. During these eight months, I did not see menstruation. The release was halted. However, the surgical site continues to hurt. I’m here today to see if the menstrual cycle is absent and if we can have at least one more child (30-year-old gravida four mother).

Women who have survived uterine rupture also face social stigma or discrimination due to misconceptions about the causes of the condition:

I think this pregnancy was meant to be my demise. Following the procedure, my life changed. My spouse and kids don’t give a damn about me. No one should come to me and remain with me because of the terrible stench. Because of the awful stink, no one has given me food. I’m not as hungry, either. They wish me to be excluded from the house (a 31-year-old para 4 mother).

A key informant added that the recovery process can be physically demanding and emotionally draining, requiring support from healthcare providers, family members, and community resources.

… After surgery, their recovery can take longer. Their injuries did not heal quickly either. The explanation could be that their nutritional state impacts the healing process (a 37-year-old female midwife with 16 years of experience).

Consequences

Uterine rupture had devastating consequences for women, leading to maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Women who survive uterine rupture experience long-term health complications, such as infertility, impacting their physical and emotional well-being. These impacts were multi-faceted and included physical, psychological, social family relationships, infertility, and Emotional.

Emotional and psychological consequences

For many women, the experience of uterine rupture was a traumatic and life-altering event, shattering their sense of physical well-being and reproductive potential. The sudden rupture of the uterus during childbirth leads to severe complications, including bleeding, infection, and the loss of the unborn child. The emotional aftermath of such an event was overwhelming, with feelings of grief, guilt, and trauma often lingering long after the physical wounds had healed.

I can’t control urine. There is a foul odour that results from my uncontrolled urine, and I change clothes often daily. I have no sexual interest, and I only do sexual intercourse for the sake of my husband. However, It is not comfortable for both of us. My husband’s family also detached from me due to the foul odour. Even I can’t be involved in social activities because my odour is uncomfortable for others, and they cover their nose while passing near me. So, I was demoralised and felt shame (34 years old, para 5 mother).

Infertility

Infertility resulting from uterine rupture adds another layer of complexity to the emotional landscape as women grapple with the loss of their ability to conceive and carry a child. The dream of motherhood was shattered, leaving a profound sense of emptiness and longing for what could have been. Women experience feelings of inadequacy, shame, and isolation as they navigate the challenges of infertility in the aftermath of uterine rupture.

My husband is unhappy because I can’t meet his needs. My periods have stopped, and my involvement in social activities with neighbours has decreased. Due to my illness, I can’t fulfil the expectations placed on me, and even routine activities have become difficult (39-year-old para 5 mother).

Another mother added:

My husband supports me for now, but I don’t know what will happen. Hey, I may need an extra child, and change it for me because I can’t give birth. I fear the future because I can’t give birth, I am challenged with back pain and abdominal pain, and I feel numbness in my foot (a 26-year-old para three women).

A key informant added:

There are many complications, such as the inability to give birth and the absence of menstruation. Some women develop fistula and face difficulty walking due to these complications. This situation profoundly affects their lives and their families. Many women desire children but cannot give birth, and urine incontinence causes a bad odour, leading to social stigma. As a result, they often prefer to stay alone at home. Additionally, some women who develop fistula are separated from their husbands and families, which can lead to psychological problems (a 39-year-old male gynecologist and obstetrician with nine years of experience).

Urinary incontinence

Urine incontinence further compounds the emotional and psychological impact of these experiences as women struggle to come to terms with the loss of control over their bodies. The constant fear of leakage and embarrassment erodes self-esteem and confidence, leading to feelings of shame and isolation. Women feel stigmatized and misunderstood as they navigate the challenges of living with a condition that is often hidden and taboo.

The pee smells unpleasant if the underwear is not regularly changed and washed. As a consequence, people might point at me. I’m afraid that others might laugh at me if they find out that I’m unable to give birth. That’s why I like to be at home (32 years old, para 5 mother).

Daily life and relationships consequences

In their daily lives, these women face a myriad of challenges stemming from the aftermath of uterine rupture. The physical scars left by this traumatic event serve as constant reminders of their vulnerability and mortality, influencing how they move, work, and care for themselves and their families. The pain and discomfort associated with uterine rupture can limit their mobility, energy levels, and overall quality of life, making even simple tasks a struggle.

After the operation It is difficult to raise my foot and walk. I can’t do routine activities like walking; feel numbness on the foot immediately while walking (31-year-old para 4 mother).

A key informant added:

These women are called high-risk women. They are also psychological victims. We will meet after week one or week two. Some of them complain of weakness of the leg or urine incontinence, which results in low self-esteem. It affects their family and social life, like the coffee ceremony, meeting, marketplace, and even their bed being separated from their husbands due to foul odor (38 years old, Integrated emergency surgical officer, five years experience).

Coping and resilience techniques

In sharing their stories, women’ narratives underscored the transformative power of love, faith, and self-care in navigating the challenges of physical and emotional trauma. Through their strength, courage, and determination, these women exemplified the indomitable spirit of resilience that can appear from moments of profound vulnerability and adversity.

Even if brutal, I tolerate and try my best in daily activities and social issues as much as possible (a 28-year-old para 3 mother).

Another participant added:

I accept everything and try to adapt with the help of God. We have another child, and my husband also supports me. Still, my fear is as it is because even I can’t see the menstruation cycle and give birth (a 39-year-old para 5 woman).

In the quiet solitude of self-isolation, women who have survived uterine rupture and developed fistula find a sanctuary for healing:

No. I don’t want to tell anybody. I prefer to be alone at my home. If somebody heard about my infertility, it would disturb our relationship, and now this is happening in my family. So, I come to confirm whether I can get a baby or not to be sure (a 28-year-old para 3 mother).

Removed from the din of the outside world, women create a sacred space where their stories can be heard without judgment or pity. In this quiet sanctuary, the women support each other, sharing their experiences, fears, and hopes. They form a bond forged in resilience and understanding, finding strength in their collective journey towards healing:

Women from urban areas used modes and clothes to prevent urine leakage. However, those who come from rural areas are not aware of this. Most of them prefer to be at home. They seek health care after a long period. I know the mother who came after eight years. The operation was done in 2005, and she came in 2013. She was limited to home because there was a foul odour from the urine, which affected her psychologically and socially (a 38-year-old male midwife with 15 years of experience).

In a remote village nestled amidst lush greenery and rolling hills, women who have survived the harrowing ordeal of uterine rupture and developed fistula find themselves at a crossroads. They stand at the intersection of tradition and modernity, grappling with the decision of whether to rely on traditional medicines or seek modern treatment for their condition. With deep roots in their cultural heritage, the women are well-versed in the healing properties of traditional herbs and remedies passed down through generations:

As I told you, I still apply honey and coffee to the wound. I wash and change the clothes to prevent the foul odor due to urine incontinence. I tried to hide my husband, family, and neighbors. However, I can’t tolerate especially the pain and itching on the surgical site, which is why I came today (a 38-year-old para 7 mother).

Discussion

This study identified themes including the experience during diagnosis and initial symptoms, the risk factors of uterine rupture, management-related issues, challenges, impacts, and coping and resilience.

Similar to other studies [26, 27], in this study, the initial experience of symptoms of uterine rupture for women was a deeply distressing and alarming ordeal, marked by intense physical pain, emotional turmoil, and a sense of profound vulnerability. For many women, the onset of uterine rupture was sudden and unexpected, catching them off guard and plunging them into a state of shock and disbelief. The initial symptoms included severe abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, rapid heartbeat, dizziness, and a sense of impending doom. These physical manifestations were overwhelming and incapacitating, causing immense distress and fear. As the uterine rupture progresses, the pain intensifies, spreading throughout the abdomen and radiating to other parts of the body. Women experienced more frequent and intense contractions than normal, as well as a feeling of pressure or fullness in the pelvis. Sometimes, the baby’s heart rate becomes abnormal, signalling a critical situation requiring immediate medical attention. Emotionally, women felt a sense of helplessness and despair as they grappled with the realization that their health and the well-being of their babies were in grave danger. The uncertainty and fear surrounding uterine rupture led to feelings of anxiety, panic, and a profound sense of loss. Women also experienced guilt, questioning whether they could have done something differently to prevent this complication. The initial experience of symptoms of uterine rupture was a pivotal moment in a woman’s life, reshaping her understanding of her own body, her pregnancy, and her future as a mother. It is a time marked by intense vulnerability and uncertainty as women navigate the complex terrain of medical emergencies and life-threatening complications.

On the other hand, for women who have survived uterine rupture, the experience of obstetric delays exacerbated the already critical situation they faced. These delays occurred at various stages of the obstetric care continuum, including delays in recognizing the signs and symptoms of uterine rupture, delays in reaching a healthcare facility, and delays in receiving proper treatment and interventions. One of the key challenges faced by women who have survived uterine rupture was the delay in recognizing the signs and symptoms of this life-threatening complication. The uterine rupture could be presented with a wide range of symptoms, including severe abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and abnormal fetal heart rate, which might be mistaken for other less severe conditions. This lack of recognition led to a delay in seeking medical help, potentially worsening the outcome for both the mother and the baby [5].

Furthermore, in line with a study in Eritrea [28], women in this study encountered delays in reaching a healthcare facility equipped to manage this obstetric emergency. In many cases, women might live in remote or underserved areas where access to emergency obstetric care is limited or non-existent. Similarly, similar to other studies [2], the lack of transportation, infrastructure, or financial resources could impede their ability to promptly reach a hospital or healthcare provider, further complicating their situation. Once women who have survived uterine rupture do reach a healthcare facility, they may face more delays in receiving appropriate treatment and interventions. In some cases, healthcare providers may lack the necessary skills, training, or resources to manage uterine rupture effectively, leading to further delays in providing life-saving care. The availability of essential obstetric supplies, medications, and equipment may also be limited, hindering timely and quality care. The cumulative impact of these obstetric delays on women who have survived uterine rupture can be profound and long-lasting. The physical and emotional trauma of experiencing a life-threatening obstetric complication, coupled with the challenges of navigating a healthcare system marked by delays and deficiencies, can leave women feeling vulnerable, scared, and disillusioned.

The challenges experienced by women who have survived uterine rupture were profound and multi-faceted, encompassing physical, emotional, psychological, and social dimensions. These challenges had a lasting impact on a woman’s health, well-being, and quality of life, as well as her relationships and sense of self. Physically, women who have survived uterine rupture face a myriad of challenges related to their recovery and ongoing health. The physical trauma of uterine rupture resulted in severe blood loss, organ damage, infection, and other complications that require extensive medical intervention and long-term care. Women endured multiple surgeries, prolonged hospital stays, and a lengthy rehabilitation process to address the immediate consequences of uterine rupture and its aftermath. The physical pain, discomfort, and limitations associated with these interventions were overwhelming and debilitating, impacting a woman’s ability to perform daily activities and care for herself and her family.

Moreover, emotionally and psychologically, surviving uterine rupture triggered a range of complex emotions and reactions that profoundly affect a woman’s mental health and well-being. In line with the study in Ghana [21], women experience feelings of fear, anxiety, depression, grief, guilt, and shame as they process the trauma of their experience and navigate the challenges of recovery. The emotional toll of uterine rupture was overwhelming, leading to symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), insomnia, panic attacks, and other mental health issues that disrupt a woman’s sense of safety, security, and self-worth. In line with a Malawi study [29], socially, women who had survived uterine rupture encountered stigma, discrimination, and isolation due to the perceived failure or inadequacy of their bodies to sustain a healthy pregnancy. Society’s expectations of women as women and caregivers further worsen feelings of guilt, shame, and self-blame among survivors of uterine rupture. Women struggled to find understanding, support, and validation from their families, friends, healthcare providers, and communities, leading to feelings of loneliness, alienation, and disconnection from others.

Similar to a study conducted in Rwanda [30] and Ethiopia [31], women who have survived uterine rupture demonstrate remarkable coping strategies and resilience in the face of profound physical, emotional, and social challenges. These women draw upon their inner strength, resourcefulness, and support networks to navigate the complexities of recovery and healing. Qualitatively exploring the coping and resilience techniques experienced by survivors of uterine rupture sheds light on the adaptive strategies they employ to cope with adversity, rebuild their lives, and find meaning and purpose in the aftermath of such a traumatic event.

One key coping strategy that women who have survived uterine rupture often employ is seeking support from their loved ones, healthcare providers, and communities. By sharing their experiences, emotions, and concerns with others, survivors can feel validated, understood, and less alone in their journey toward healing. Connecting with fellow survivors through support groups, online forums, and peer networks can also provide a sense of solidarity, empowerment, and hope for the future. By building a strong support system, women can access the emotional, practical, and informational resources they need to cope with the challenges of recovery and rebuild their lives after uterine rupture.

Another coping strategy that women who have survived uterine rupture often utilize is engaging in self-care practices that promote their physical, emotional, and mental well-being. This may include prioritizing rest, nutrition, exercise, and relaxation techniques to support their recovery process and manage stress. Women may also explore complementary therapies such as yoga, meditation, mindfulness, art therapy, or counseling to address the emotional trauma and psychological impact of uterine rupture. By taking care of themselves holistically, survivors can enhance their resilience, coping skills, and overall quality of life as they navigate the challenges of healing and recovery.

Furthermore, women who have survived uterine rupture showed a sense of purpose, meaning, and resilience in their journey toward healing. By reframing their experience as a source of strength, growth, and empowerment, survivors found meaning in their suffering and used it as a catalyst for personal transformation and positive change. Engaging in advocacy, education, or outreach activities related to uterine rupture also helped survivors reclaim their voice, agency, and sense of control over their narrative. By turning their pain into purpose, women inspired others, raised awareness, and fostered a sense of community and solidarity among survivors of uterine rupture.

Conclusions

Overall, the initial experience of symptoms of uterine rupture for women was a profound and transformative journey that underscores the fragility of life, the power of maternal instinct, and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity. It is a testament to the strength and courage of women who navigate the complexities of pregnancy and childbirth with grace and determination, even amid unforeseen challenges. The obstetric delays experienced by women who have survived uterine rupture underscore the urgent need for improved access to timely and quality obstetric care for all pregnant women. Addressing these delays requires a multi-faceted approach that includes investments in healthcare infrastructure, training of healthcare providers, community education, and policy reforms to ensure that every woman receives the care she needs when facing obstetric emergencies like uterine rupture. The challenges experienced by women who have survived uterine rupture were also deeply personal, complex, and multi-faceted, encompassing physical, emotional, psychological, and social dimensions. These challenges can profoundly impact a woman’s health, well-being, relationships, and sense of self. By qualitatively exploring these challenges, we can gain a deeper understanding of the unique experiences of survivors of uterine rupture and work towards providing them with the support, resources, and care they need to heal, recover, and thrive in the aftermath of such a traumatic event. Moreover, the impacts experienced by women who have survived uterine rupture are far-reaching and complex, encompassing physical, emotional, psychological, and social dimensions. Addressing these impacts requires a holistic approach that prioritizes women’s health and well-being, provides comprehensive support services, and promotes awareness and understanding of the challenges faced by survivors of obstetric complications like uterine rupture. By acknowledging and addressing these impacts, we can empower women to heal, recover, and thrive in the aftermath of such a traumatic event. Women who have survived uterine rupture exhibit remarkable coping strategies and resilience in the face of profound physical, emotional, and social challenges. By seeking support, engaging in self-care practices, and finding purpose and meaning in their experience, survivors navigated the complexities of healing and recovery with strength, courage, and grace. Through qualitative exploration of these coping and resilience techniques, we can gain a deeper understanding of the adaptive strategies employed by survivors of uterine rupture and work towards providing them with the support, resources, and care they need to heal, recover, and thrive in the aftermath of such a traumatic. Thus, the findings of this study provide valuable insights into the complex and multi-faceted nature of uterine rupture, shedding light on the experiences of those affected by this condition. By understanding the challenges faced by individuals with uterine rupture and the coping mechanisms they employ, healthcare providers can enhance their care and support services to meet the needs of this vulnerable population better. This study contributes to the body of knowledge on uterine rupture and informs future research and clinical practice in obstetric care.

Acknowledgements

The authors are obliged to all participants who willingly participated in this study. We want to thank Jimma University Faculty of Public Health for allowing this study to be conducted. We would also like to thank each Nekemte Hospital staff member, manager, and data collector for their cooperation.

Author contributions

MG, GT, and BW conceived and planned the study protocol involving data transcription, coding, and the manuscript’s write-up. MG implemented and supervised the fieldwork and drafted the manuscript. MG, GT, and BW critically reviewed the analyzed data and prepared the final manuscript. All authors read, agreed, and approved the last version of the manuscript and approved both to be personally responsible for the author’s contributions and ensure that questions linked to the accuracy or truthfulness of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, were appropriately investigated.

Funding

This study is the research work of the first author’s Ph.D. program. He received funding from Jimma University, Ethiopia, to pursue higher Ethiopian studies. However, the sponsoring organisations had no role in study design, data collection, analyses, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data are kept in the manuscript. However, full access to the Data will be made available at the reasonable request of the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures used in human clinical data studies adhered to the institutional and national research committee’s ethical requirements, the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and subsequent revisions or comparable ethical standards. The IRB of Jimma University (Ref No JUIH/IRB/587/23) and the Institutional Review Committee of Wallaga University (Ref No CMHS/21/2014 GC) waived the written informed consent requirements as well as ethics approval or were deemed unnecessary according to national regulations as the data used were secondary data from a patient’s records. The World Health Organization’s ethical and safety recommendations for exploring sensitive topics were observed [32].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tao J, Mu Y, Chen P, Xie Y, Liang J, Zhu J. Pregnancy complications and risk of uterine rupture among women with singleton pregnancies in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaye DK, Kakaire O, Nakimuli A, Osinde MO, Mbalinda SN, Kakande N. Lived experiences of women who developed uterine rupture following severe obstructed labor in Mulago hospital, Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2014;11(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filippi V, Ganaba R, Baggaley RF, Marshall T, Storeng KT, Sombié I, Ouattara F, Ouedraogo T, Akoum M, Meda N. Health of women after severe obstetric complications in Burkina Faso: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desta M, Amha H, Anteneh Bishaw K, Adane F, Assemie MA, Kibret GD, Yimer NB. Prevalence and predictors of uterine rupture among Ethiopian women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0240675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amikam U, Hochberg A, Segal R, Abramov S, Lavie A, Yogev Y, Hiersch L. Perinatal outcomes following uterine rupture during a trial of labor after cesarean: a 12-year single-center experience. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;165(1):237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Admassu A. Analysis of ruptured uterus in Debre Markos Hospital, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2004;81(1):52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mengesha MB, Weldegeorges DA, Hailesilassie Y, Werid WM, Weldemariam MG, Welay FT, Gebremeskel SG, Gebrehiwot BG, Hidru HD, Teame H et al. Determinants of Uterine Rupture and Its Management Outcomes among Mothers Who Gave Birth at Public Hospitals of Tigrai, North Ethiopia: An Unmatched Case Control Study. Journal of Pregnancy 2020, 2020:8878037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Gebretsadik A, Hagos H, Tefera K. Outcome of uterine rupture and associated factors in Yirgalem general and teaching hospital, southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangun M, Mangundap SA, Idrus HH. Survival status and predictors of Mortality among women with uterine rupture at Public hospitals of Eastern Ethiopia. Int J Women’s Health 2023:701–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Alemu A, Yadeta E, Deressa A, Debella A, Birhanu A, Heluf H, Mohammed A, Ahmed F, Beyene A, Getachew T. Survival status and predictors of mortality among women with uterine rupture at public hospitals of eastern Ethiopia. Semi-parametric survival analysis. Int J Women’s Health 2023:443–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Groenewald T. A phenomenological research design illustrated. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2004;3(1):42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodgson JE. Phenomenology: researching the lived experience. J Hum Lactation. 2023;39(3):385–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell K, Ranfagni S. Demystification and actualisation of data saturation in qualitative research through thematic analysis. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2024;23:16094069241229777. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H, Jinks C. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2015;42:533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell S, Greenwood M, Prior S, Shearer T, Walkem K, Young S, Bywaters D, Walker K. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(8):652–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Sage; 2014.

- 18.Bailey N, Mandeville KL, Rhodes T, Mipando M, Muula AS. Postgraduate career intentions of medical students and recent graduates in Malawi: a qualitative interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodges BD, Albert M, Arweiler D, Akseer S, Bandiera G, Byrne N, Charlin B, Karazivan P, Kuper A, Maniate J. The future of medical education: a Canadian environmental scan. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Melle E, Lockyer J, Curran V, Lieff S, St Onge C, Goldszmidt M. Toward a common understanding: supporting and promoting education scholarship for medical school faculty. Med Educ. 2014;48(12):1190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mwini-Nyaledzigbor PP, Agana AA, Pilkington FB. Lived experiences of Ghanaian women with obstetric fistula. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(6):440–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Evaluation. 2006;27(2):237–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R. Qualitative research practice. Volume 757. sage London; 2003.

- 24.Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng MF, Zhang XD, Zhang QF, Liu J. Uterine rupture in patients with a history of multiple curettages: two case reports. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(24):6322–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flis W, Socha MW, Wartęga M, Cudnik R. Unexpected uterine Rupture—A Case Report, Review of the literature and clinical suggestions. J Clin Med. 2023;12(10):3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molzan Turan J, Johnson K, Lake Polan M. Experiences of women seeking medical care for obstetric fistula in Eritrea: implications for prevention, treatment, and social reintegration. Glob Public Health. 2007;2(1):64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeakey MP, Chipeta E, Taulo F, Tsui AO. The lived experience of Malawian women with obstetric fistula. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11(5):499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semasaka Sengoma JP, Krantz G, Nzayirambaho M, Munyanshongore C, Edvardsson K, Mogren I. Not taken seriously: a qualitative interview study of postpartum Rwandan women who have experienced pregnancy-related complications. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Donnelly K, Oliveras E, Tilahun Y, Belachew M, Asnake M. Quality of life of Ethiopian women after fistula repair: implications on rehabilitation and social reintegration policy and programming. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(2):150–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Organization WH. WHO ethical and safety recommendations for researching, documenting and monitoring sexual violence in emergencies. 2007.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are kept in the manuscript. However, full access to the Data will be made available at the reasonable request of the corresponding author.