Abstract

One of the most common health concerns disturbing people within working years globally is diabetes mellitus (DM). One well-known consequence of DM is vascular damage, which can manifest as macro- and microangiopathy affecting the ocular retina. Therefore, Diabetic macular edema (DME) is a major sight-threatening complication of diabetic retinopathy (DR) worldwide. It is the most prevalent cause of significant vision impairment in diabetic patients. Long-term vision loss can be avoided by following early DME treatment guidelines in everyday life. Hence, there are various therapeutic approaches for DME management. Currently, the first-line treatment for DME is anti-VEGF family drugs, such as ranibizumab, brolucizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept. Nevertheless, relapses of the disease, inadequate response, and resistance during anti-VEGF therapy are still seen because of the intricate pathophysiological foundation of the disease. Consequently, there is an excellent requirement for therapeutic approaches to advance and become better at controlling diseases more satisfactorily and require fewer treatments overall. We conducted a thorough literature search in the current review to present a comprehensive overview of the primary data about the current DME therapeutic agents. We also covered the novel advances in DME management and probable future treatments being investigated and developed. This review recommended that Large clinical trials should afford sufficient evidence to support these innovative treatment modalities.

Keywords: Diabetic macular edema, Anti-VEGFs, Diabetes mellitus, Proliferative diabetic retinopathy, Selective retinal therapy

Background

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is one of the significant causes of irreversible visual impairment and subsequent permanent vision loss and blindness. It is currently on an exponential rise due to its prevalence in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2, which is considered a global epidemic of the modern era with about 382 million individuals currently affected worldwide, expected to reach 592 million by the year 2035 and 783.2 million in 2045, this increase is mainly attributed to the rising prevalence of obesity and prolongation of the average human life expectancy [1, 2]. It was found that about 10.2% of 22,896 diabetic patients had diabetic retinopathy, and 6.81% had DME [3]. DME is a term used to describe retinal thickening in or around the center of the macula. This persistent macular edema primarily affects and damages the retinal neuromuscular system, leading to diabetic retinopathy and disturbed visual acuity. This edema is mainly mediated by the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which leads to increased permeability, obstruction and damage of the retinal capillaries, resulting in serous blood components leakages and hemorrhages and, ultimately, failure of the neurovascular units (NVUs) of the retina [4, 5].

Early detection of these changes by periodic checkups of diabetic patients with optical coherence tomography (OCT) is crucial in setting up effective measures for DME prevention, early management and control. These measures include hyperglycemia and blood pressure control and Specific ophthalmic treatments such as intravitreal anti-VEGF drug injections, intravitreal corticosteroid injections, focal laser photocoagulation, and vitrectomy [2, 4, 6]. Although the introduction of anti-VEGF has revolutionized our understanding of DME, there are still so many cases resistant to treatment, with many responding to steroids, all further support the idea of DME being of multifactorial origin [6, 7]. In this narrative, the authors thoroughly review the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnostic modalities, and current and promising frontiers for treating patients with DME.

Pathophysiology of DME and DR

Patients usually remain asymptomatic for years before the typical manifestations of DR start to take place. They can be clinically diagnosed, making early diagnosis of the disease complex for apparently healthy individuals. However, it has been objectively accepted that many noticeable changes occur during the disease’s asymptomatic phase in the retina, especially at the periphery, affecting the retinal, endothelial, and ganglionic cells in the eye, resulting in gradual cellular and functional disability. These changes are also a critical reflective indicator of systemic diabetic microvascular complications [8].

As a result of the insufficient action of insulin in a diabetic patient, Glucose tends to build up in the bloodstream, leading to hyperglycemia. It alters the membrane permeability and elasticity of blood vessels, resulting in micro-aneurysms, microscopic hemorrhages, deposition of hard exudates and endothelial and pericyte cell damage resulting from a chronically high glycemic index, mainly in uncontrolled diabetic patients. Still, it also occurs with controlled DM as a long-term, slowly developing complication [9].

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy is the advanced stage of the disease; it is characterized by neovascularization and increased severity of symptoms from NPDR.

As the micro-vascular pathology and damage in the capillary beds of the retina progresses, there will be resultant hypoxia of the retina due to lack of blood supply, hyperglycemia along with hypoxia lead to the release of cytokines, chemokines which result in inflammation and glial cell activation, and release of vascular growth factors most notably VEGF, to restore circulation by forming new vessels on the optic disc and elsewhere on the retina, in a process termed neovascularization [9].

VEGF and the other released growth factors and proinflammatory molecules induce a decrease in the vascular adhesion molecules VCAMs between the endothelial cells, an increase in subclinical inflammation and production of nitric oxide resulting in vasodilation, and the upregulation of multiple metabolic pathways that ultimately result in increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and the accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) thus disrupting the cellular activities and damaging the DNA [10].

Therefore, markers like VCAMs, VEGF and erythropoietin, among others, show increased levels in the blood with the progression of clinical and subclinical retinopathy; these markers provide promising targets for early diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of disease severity [11].

As a result, it can lead to increased retinal thickness, maculopathy and macular edema, neurodegeneration and further damage to the blood-retinal barrier [12].

Diabetic maculopathy can be defined as the presence of DR in and around the macula, resulting in diabetic macular edema that is focal or diffuse, accumulation of hard exudates, micro-hemorrhages and retinal thickening in the macula. DME can start developing at any stage of the disease but is usually associated with more advanced presentations, as in severe NPDR and PDR, it is considered the leading cause of vision loss among DR pathologies [13].

All these factors contribute to the symptoms observed in patients of PDR, as they usually present with progressively worsening vision or sudden blindness, scotomas and other shapes in the field of vision, redness, sore eyes and even lead to the advanced presentations of PDR like vitreous hemorrhages and retinal detachments involving or sparing the macula [14].

Risk factors for DR can be either physiological, as in pregnancy, obesity or puberty. Or pathological, as in High BP, Kidney disease, Uncontrolled T1DM, Oxidative stress and poor levels of lipids, proteins, vitamin D or glucose in the blood. Chronic hyperglycemia is the most important and predictive factor for both the progression and control of the disease, as it was clearly shown in many trials that very intensive glycemic control can reduce the incidence of DR by up to 62–85% [15, 16].

More Recent studies have shown that endothelial nitric oxide synthase eNOS gene polymorphisms may play a significant role in the upregulation of eNOS, especially in the Caucasian population, triggering an increased production of nitric oxide, which is an essential factor in the elevated levels of Superoxides responsible for the significant damage to the retinal microvasculature. Therefore, research on eNOS gene polymorphisms on chromosome 7q35-36 and its relation to DR suggests that it could be a crucial marker for the early diagnosis of retinal disease in the Western world [17] (see Fig. 1).

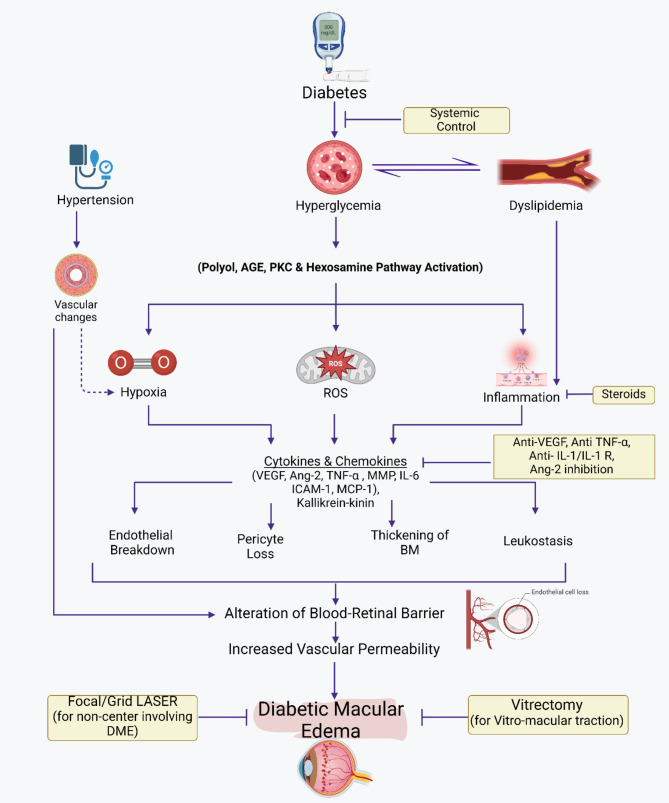

Fig. 1.

The pathogenesis of diabetic macular edema and management strategies. Illustrates the progression and effects of DME. It begins with conditions such as Hyperglycemia which could be associated with aggravating factors (i.e. hypertension), leading to Biochemical and Molecular Abnormalities. These abnormalities trigger a series of cellular and molecular reactions, including the generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and its effects. These effects include inflammation, endothelial cell junction breakdown, pericyte loss, thickening of the Basement Membrane (BM), and leukostasis. These processes alter the blood-retinal barrier and increase vascular permeability, resulting in Diabetic Macular Edema. The figure indicates current available treatments like Anti-VEGFs, Steroids, Systemic treatments, Focal/Grid Laser (for DME involving the center) and Vitrectomy (for Vitreo-macular traction).

Prognosis and life quality

Long-term visual acuity may benefit from early DME treatment with rigorous therapy before alterations in the outer retinal layers occur. Still, late-treated DME eyes require more injections and focal laser treatments than early-treated eyes. Real-life adherence to early DME therapy will help avoid long-term visual loss [18]. On the other hand, timely treatment can help preserve residual vision even in individuals who present with visual loss later in life [19]. However, the influence of gender on VTDR was only slightly significant, whereas the effect of age on VTDR and CSME prevalence was not statistically significant [20]. DME can result in permanent. Retinal alterations and chronic edema if treatment is not received, which would compromise vision. According to studies, 20–30% of DME patients will lose at least three lines of vision within three years if the disease is not treated [21]. Patients may refuse treatment for several reasons, such as mild-to-moderate vision loss, a deranged glucose level, fear of repeated injections and procedure-related complications, incapacity to attend on-schedule and regular follow-up appointments, and, most importantly, treatment costs [22]. Controlling systemic risk factors, such as strict management of hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, should be viewed as the cornerstone approach for the prevention and treatment of DR and DME, as DME is still a frequent DR consequence brought on by diabetes [23, 24].

Current diagnostic modalities

Fluorescein angiography is the most widely used ophthalmological screening test for the detection of microvascular abnormalities in the retina and the choroid, where the color fundus mydriatic 7 Standard Field 7SF 30° has been regarded as the first-line gold standard retinal examination method for detection of DR as defined by the ETDRS [25, 26]. During the procedure, seven different fields are taken with the fundus camera through a contact lens, Providing maximal sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis. As a result, this procedure can be time-consuming for the patient and highly dependent on the reader’s skill and compliance of the patient. Therefore, including fewer fields is often more practical and attractive to use in a clinical setting; this comes with the obvious drawback of decreased field of view. They decreased sensitivity and selectivity to 78% and 86%, respectively, for single-field and down to 92% and 97% for 3-field fundus photography, showing relatively high agreement with 7SF in detecting clinical DR. The 7SF and < 7SF provide limited exposure to the peripheral retina. Hence, it has limited use for the early detection of DR compared to other tests [25, 26].

The ultra-wide field is another imaging technology that utilizes confocal laser scanning ophthalmoscopy to produce high-quality images with much broader peripheral retinal coverage, enabling visualization of up to 200° in a single frame. It is now well-documented that peripheral retinal abnormalities are one of the first signs of asymptomatic damage to the retina. Therefore, UWF has become more valuable in the early detection of DR than 7SF. Mydriatic-UWF has also shown high to near-perfect agreement with 7SF in diagnosing PDR and DME. As a result, UWF has recently been considered the primary screening device for diagnosis of DR. However, 7SF is still much more cost-effective, especially in developing nations [27, 28].

Along with the continued rise in cases and relevance of DR in the world, Cost-effective diagnostic modalities make for an attractive goal for the systematic detection in the populace, with methods like non-mydriatic Tele-retinal technology being more easily accessible, cost-effective, and decrease the rising overload on the medical staff. Another candidate for diagnosis is Budget smartphone-based fundus cameras for retinal photography; compared to routine evaluation, these methods are associated with a lower overall sensitivity and high specificity for the detection of retinopathy, being more sensitive and selective for more severe disease presentations like PDR and severe NPDR compared to mild and subclinical NPDR. Therefore, it provides valuable prospects for detecting DR, especially in developing countries [29, 30].

Optical Coherence Tomography: is a non-invasive cross-sectional diagnostic method that relies on the exposure of infrared radiation on the retina and measuring the reflection delay time, thereby constructing high-quality 2 and 3-dimensional sections of the retina, providing much more sensitive evaluation of DME and retinal thickness, this method mitigates one of the significant drawbacks of fundus photography; the inability to accurately assess the extent and severity of DME and central foveal thickening, resulting in a lack of essential prognostic markers that are crucial in the treatment decision [31].

OCT provides an objective optical biopsy of the retina without the need for skilled operators; it offers a comparatively shorter examination time and is less invasive and better tolerated compared to fundus photography; the increased sensitivity and selectivity in DME assessment observed with OCT make it the primary method for early and definitive diagnosis. Moreover, it also compares favorably with UWF in diagnosing DR pathologies [32].

Methods

Literature search strategy

We piloted a broad literature search to conduct a comprehensive narrative review on DME until the 15th of February, 2024. The exploration was accomplished through several electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science, to identify relevant publications, including research articles, reviews, clinical trials, and case reports published up to the current date. The authors employed a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms such as “Diabetic Macular Edema,” “Diabetic Retinopathy,” “DME Management,” “DME diagnosis,” “Anti-VEGFs for DME,” “DME pathogenesis,” “DME treatment,” and correlated terms. A variety of search terms were used to gather a wide range of literature that is pertinent to the objectives of the review. The search focused on the underlying pathophysiology, epidemiological and prognostic trends, available diagnostic tools, currently approved treatments, advantages and limitations, and the up-to-date advancements in treatment options for diabetic macular edema (DME). Titles and abstracts were carefully reviewed to ensure they aligned with the purposes of the review. This was followed by a comprehensive analysis of the full-text articles to determine if they met the criteria for inclusion. Excluded from the review were publications that were duplicates or did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to guide the selection of literature for review.

The inclusion criteria were:

Relevance to the topic and content related to diabetic macular edema (DME) pathophysiology, prognostics, diagnosis, and therapeutic updates.

Only peer-reviewed, English-language articles were included.

Studies published before the knowledge cutoff date of 15th February 2024 were included.

Only studies with available full-text access were included.

The exclusion criteria were:

Articles were not relevant to the purpose of our review.

Duplicates or unavailable in full-text format.

Articles and reports not written in English were excluded.

Results of current DME treatments

Anti-VEGFs

Ranibizumab

Ranibizumab, also known as Lucentis, is the first anti-VEGF to receive FDA approval for the treatment of Diabetic macular edema(DME) in August 2012, based on results of phase III RISE and RIDE clinical trials which showed 44.8% of patients with DME gained ≥ 15 letters in comparison with 18% in control patients receiving sham injections [33]. In addition to proven efficacy in Protocol I [34, 35], RESTORE phase III trial [36], and other real world and RCTs [37, 38]. Ranibizumab is the Fab fragment of humanized monoclonal IgG, and it acts by blocking VEGF-A. Thereby preventing the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier, leakage of blood vessels and neovascularization. It is also used in the treatment of wet AMD (wAMD), macular edema caused by retinal vein occlusion (RVO), diabetic retinopathy, Myopic Choroidal Neovascularization (CNV) and retinal ischemia [33, 39].

Ranibizumab intravitreal injections (IVR) come in 0.3 mg and 0.5 mg vial dosages given under local anesthesia or via Prefilled single-use syringes, which have been recently introduced. The recommended dose for treating DME is 0.3 mg intravitreal injections each month [33]. Given the need for repeated injections of ranibizumab in various treatment regimens to meet and maintain desirable outcomes, administration of ranibizumab through portal delivery system (PDS) was approved to be used instead for treatment of wet AMD to ensure continuous delivery of ranibizumab with possible same effect of traditional ranibizumab injections [40, 41] adding additional benefit of minimizing subjection to multiple injections thus reducing treatment burden and improve patients satisfaction.

Several factors have been found to influence the variability of response to the treatment, including non-response or worsening symptoms. A small retrospective case series included DME patients receiving only IVR injections. They concluded that OCT biomarkers can aid in predicting the one-year response to IVR Injections in terms of improvement in Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and central retinal thickness (CRT) [42]. Results of a recent study investigating the association between visual acuity and structural changes showed that the outcomes of IVR injections are better predicted by decrement of subretinal fluid (SRF) area, and visual acuity gain was best estimated by reduction of the thickness of the photoreceptor layer [43]. However, given the limitations of present studies, these correlations are yet to be reliable for decisions regarding the direction of treatment and re-treatment and must be supported by sufficient evidence.

Many trials have demonstrated a well-tolerated safety profile regarding aVEGF agents with low rates of severe adverse effects. The most common ocular complications associated with IVR injections are conjunctival hemorrhage, vitreous detachment and a rise in IOP. Complications include endophthalmitis, intraocular inflammation, retinal detachment, cataract and glaucoma [44].

A study investigating the rates of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events of ranibizumab using data from previous clinical trials reported risks of arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, TIA and vascular death, regardless of the applied dose [45, 46]. Further, a recently published population-based cohort study revealed an increased risk of long-term CKD among patients receiving IVR and further supported previous data [47].

Ranibizumab lost its patent in 2020 and 2022 in the US and Europe, respectively. This allowed for the development of more cost-effective biosimilars to reduce the treatment burden and increase patient reach [48]. Biosimilars are drugs made from living cells and are similar to the original molecule in terms of safety, efficacy, biological activity, quality characteristics and immunogenicity. The first ranibizumab biosimilar agent was Razumab™, approved in India for treating wAMD, DME, and macular edema following RVO and CNV [49]. Currently, there 2-FDA approved biosimilars. FYB201(Cimerli, ranibizumab-eqrn) and SB11(Byooviz, ranibizumab-nuna) [50, 51]. Other biosimilars are being investigated, with some reaching their primary endpoints for possible approval in the future.

Aflibercept

It is a fusion protein consisting of the binding regions of human VEGF Receptors 1 and 2, fused to the Fc region of human IgG, forming what is known as “VEGF trap,” enabling them to bind to VEGF-A with higher affinity than the native receptors and more potently than ranibizumab and bevacizumab, in addition to its distinct ability to bind with VEGF-B and placental growth factor (PIGF) which differentiates it from other aVEFs [52, 53]. VISTA and VIVID trials compared the effect of using 2 mg aflibercept every 4 or every 8 weeks with laser photocoagulation on patients with DME. They concluded that significantly improved visual acuity in those receiving aflibercept compared to laser therapy [54].

Aflibercept was first approved in the US in 2011 for treatment of nAMD. It has been used widely in ophthalmological conditions for managing DME, macular edema following RVO, Diabetic retinopathy (DR) and most recently as the first pharmacological option for retinopathy of immaturity(ROP) [55].

To compare the relative efficacy of aflibercept in treating patients with centrally involved DME in comparison to other commonly used aVEGF (ranibizumab and bevacizumab), aflibercept was found to be more effective than ranibizumab and bevacizumab in patients with poor baseline visual acuity (20/50 or worse). However, there are no clinically significant differences in vision gains in cases of mild vision involvement [56, 57].

The standard dose of aflibercept is 2 mg, and intravitreal injections are given each month for the first three injections, then once every two months. (43) Aflibercept has a new FDA-approved high dose of 8 mg for DME, wAMD after showing non-inferior results in BCVA to the standard dosage of 2 mg, without any new safety concerns throughout 48 weeks from phase 2/3 PHOTON trial [58, 59]. This allows for more excellent durability through extended intervals of up to 16 weeks than the previous regimen.

To date, data from trials and real-world studies regarding systemic adverse events of different aVEGF (aflibercept, ranibizumab and bevacizumab) are conflicting. Similar rates of systemic adverse effects have been shown among the three study groups in some incidents [56]. Analysis of some studies revealed an increased risk of stroke among aflibercept and ranibizumab study groups about bevacizumab [60, 61].

As stated previously, CKD is a long-term outcome of intravitreal aVEGF injections, alongside the independent risk of developing CKD in diabetic patients. Thus, renal function deterioration unrelated to the DM clinical course necessitates renal biopsy and discontinuation of VEGF injections [62]. Post aVEGF injection, endophthalmitis has generally low incidence rates. However, the list of causative micro-organisms is typically expanding to involve rarely or first-time isolated species like Morganella morganii endophthalmitis case reported in a 75-year-old patient after routine intravitreal aflibercept injection [63, 64]. This risk can be minimized when using prefilled syringe preparations. Furthermore, those treated with prefilled aflibercept injections had less chance of developing ocular hypertension with vial-drawn syringes [65].

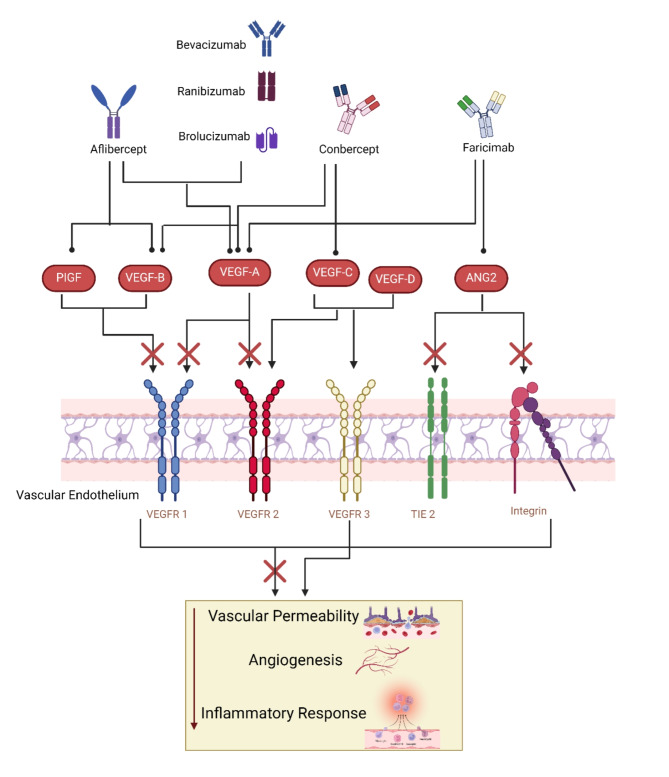

Despite the high efficacy of aflibercept, some patients show poor response to the initial. It is when some ophthalmologists might consider switching to another agent to overcome refractory results. In the case of aflibercept or ranibizumab, promising results were found when switching to faricimab regarding BCVA and extension of injection intervals [66, 67]. Overall, the selection of treatment options and frequency of injections must be adjusted according to patients’ risk factors and specific needs (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The Role of Anti-VEGF Medications in the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema. VEGF is a signal protein that stimulates the formation of blood vessels. When VEGF is overexpressed, it can lead to the vascular permeability and neovascularization seen in DME. Anti-VEGF drugs work by binding to VEGF, inhibiting its ability to bind to its receptors on the surface of endothelial cells. Different anti-VEGF drugs may have different affinities for the various VEGF receptors, which can influence their efficacy in DME management.

Brolucizumab

It is one of the novel anti-VEGFs that has already been considered as one of the new approaches to DME treatment, which is secondly approved by the FDA in 2022 after primary approval in 2019 for the wet AMD. It is created by a single-chain antibody fragment with a high affinity for suppressing VEGF-A’s ability to bind to VEGF receptors VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 [68, 69].

Compared to other anti-VEGFs, brolucizumab has a higher anti-VEGF-molar binding capacity per injection due to its low molecular weight of 26 kDa. Its low molecular weight also gives it a longer half-life and better tissue penetration [69]. An insignificant amount of net liquid volume, 50 µl, can provide 6 mg of intravitreal injection of brolucizumab, 11 times more than aflibercept [70].

Moreover, brolucizumab has been determined to be not inferior to aflibercept in the Phase 3 HAWK and HARRIER trials to treat nAMD [71]. Further, The KESTREL and KITE trials were two Phase 3 studies intended to assess the safety and effectiveness of brolucizumab in individuals with DME. Patients with DME were randomly assigned to receive either brolucizumab 3 mg, 6 mg or aflibercept 2 mg in KESTREL or brolucizumab 6 mg or aflibercept 2 mg in KITE. In these 100-week trials, it was found that Brloucizumab 6 mg, dosed up to every 16 weeks, provided clinically notable visual acuity improvements when compared to aflibercept [72].

Including the EU and the US FDA, over 40 countries acknowledged brolucizumab for treating DME-related visual impairment [73]. However, when combined with additional factors of intraocular inflammation, using brolucizumab for AMD has been shown to cause retinal vasculitis and retinal vascular occlusion [74]. While various randomized clinical trials show that intraocular inflammation with brolucizumab is not as joint in diabetic macular edema patients as it is in patients with AMD [71, 72], in the course of therapy of DME, only a single case of intraocular inflammation with vascular blockage has been documented [75].

Bevacizumab

A recombinant humanized monoclonal inhibits VEGF-A’s ability to bind to VEGF receptors VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 [76]. The FDA has approved bevacizumab for treating many malignancies but not for conditions affecting the eyes [77]. Nonetheless, bevacizumab is frequently used intravitreally off-label to wAMD as it has demonstrated encouraging outcomes in enhancing visual acuity and lowering macular edema. Compared to other anti-VEGF drugs like ranibizumab and aflibercept in many randomized clinical trials, comparable results were obtained regarding safety and efficacy. However, Bevacizumab is far less expensive than the other approved medications, making it a desirable choice for individuals and healthcare systems [78–80]. Yet, the FDA has not authorized bevacizumab, which restricts its availability and reimbursement in some circumstances.

Outlook Therapeutics, Inc. has developed (bevacizumab-vikg), a novel ocular formulation of the drug to address these concerns. This formulation aims to produce a standardized and regulated product for intravitreal usage and satisfy the FDA’s standards for a biologics license application (BLA). A critical phase 3 research (NORSE TWO) has shown encouraging results regarding the safety and efficacy of bevacizumab-vikg regarding the mean change in BCVA from baseline to week 52, being non-inferior to ranibizumab. Therefore, by mid-2022, it became the first bevacizumab ophthalmic formulation to receive FDA approval [81, 82].

In August 2022, a randomised clinical trial study was published, which involved a total of 312 eyes with DME; 158 eyes had received intravetrial aflibercept 2.0 mg monotherapy and 154 ones received intravetrial bevacizumab 1.25 mg, which later was switched to aflibercept therapy at the beginning of week 12. The two groups had no significant difference in treatment outcomes (visual acuity and retinal central thickness) over two years. These findings suggest that a cost reduction of DME treatment can be achieved since a single dose of aflibercept is about $1.830, while it is about $70 for bevacizumab [83]. Although bevacizumab had proven its safety, the aflibercept monotherapy group developed severe adverse effects in about 52% of the patients with hospitalization compared to the bevacizumab first group with a percentage of 36% for the adverse events and 32% for the hospitalization [83].

Further, a recent study concluded that administering vitamin D oral tablets and IVB injections in diabetic macular edema patients may have a significant role in visual improvement. However, it may take several months to be seen [84].

Faricimab

A new intravitreal injection is being used to treat two of the leading causes of vision loss and impairment: DME and nAMD. It is the first bispecific antibody that targets both angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) and (VEGF-A) [85, 86].

The Tie-2 receptor, which typically encourages vascular stability and maturation, is antagonistic to Ang-2 [87]. In hypoxic environments and in response to VEGF-A stimulation, Ang-2 expression is elevated, which causes Tie-2 deactivation, endothelial dysfunction, increased vascular leakage, inflammation, and angiogenesis [53, 88]. Additionally, Ang-2 increases endothelial cells’ sensitivity to VEGF-A’s actions, generating a positive feedback loop that intensifies vascular damage. By blocking VEGF-A and Ang-2 simultaneously, faricimab breaks this vicious cycle and restores the stability and integrity of the blood vessels. Due to its distinct Cross MAb structure, faricimab can attach to two targets with high affinity since it contains two distinct antigen-binding domains on a single antibody molecule [89, 90].

Several phase 3 clinical trials for DME and nAMD have shown faricimab’s efficacy and safety. Faricimab demonstrated no inferiority to aflibercept in increasing best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at one year in the YOSEMITE and RHINE trials for DME, with over half of the patients obtaining an extended dose interval of 16 weeks by the end of the study [91].

Further, Faricimab also showed no inferiority to aflibercept in improving BCVA at one year in the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials for nAMD, with approximately half of the patients reaching an extended dosage interval of 16 weeks after the research. In both indications, faricimab was usually well tolerated and had a safety profile similar to that of aflibercept [92]. Consequently, a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 RCTs conducted by Li G. et al. in 2023 [93] shows that compared to other anti-VEGF treatments with longer dose intervals, faricimab produces non-inferior or even more significant CST improvement; however, additional long-term follow-up studies are required to reinforce these findings.

Since faricimab targets both VEGF-A and Ang-2, it is the first therapy for DME and nAMD that may potentially lessen the treatment burden while preserving or improving visual results. Health Canada and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States have approved faricimab for these indications, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK has given it good final draft guidance [85].

Further, in a prospective study conducted between November 2022 and August 2023, 28 patients were enrolled to assess the impact of faricimab on the formation and elimination of micro aneurysms (MA) following three months of injections. One eye of the patient received faricimab, with the other serving as a control. In 206, 16, and 103, aneurysms vanished, formed, and were maintained, respectively. Furthermore, the analysis showed that a size reduction was accomplished, resulting in the absence of the medium and small size MA, which, in comparison to the large-sized MA, primarily contribute to leakage [94].

Conbercept

Conbercept (Lumitin) KH902 is an alternative fusion protein of the VEGF receptor (VEGFR) used by drug developers at Chengdu Kanghong Biotech. It inhibits all variants of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and PlGF. It exhibits a solid affinity for VEGF and remains persistent in the vitreous for an extended period due to its prolonged half-life [95, 96].

After completing Phase III clinical trials, it was concluded that applying the Conbercept regimen improved BCVA) and (CMT) among patients with DME. Thus, Conbercept is now regarded as a viable option for treating DME. Nevertheless, limited research is available regarding the impact of Conbercept (IVC) in patients with DME [96]. In May 2019, Conbercept acquired marketing approval from the China State Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) to treat patients with DME [97].

This recently introduced anti-VEGF medication offers an alternative treatment option for DME, nAMD and macular edema secondary to RVO in China [98–100]. However, Conbercept has not yet been introduced into the markets of other countries. Conbercept has garnered global attention as a promising treatment due to its comparable structure to aflibercept, remarkable safety and efficacy, and more affordable cost [95].

Further, Xing P. et al. conducted a retrospective study on 30 patients, analyzing 30 eyes with DME. The study found no improvement in the patient’s eyes before they were on ranibizumab treatment. However, they demonstrated functional improvement upon switching to Conbercept, including enhanced BCVA during at least 6 months of follow-up, suggesting the possibility of reversing functional impairment [101].

Moreover, Zhu Z. et al. found that patients with (DME) experienced enhancements in the size of the foveal avascular zone (FAZ) and the density of superficial blood vessels after receiving an intraocular injection of Conbercept. These improvements were particularly significant in patients with diabetic macular ischemia (DMI) at baseline. The injections were administered using the 3 + pro re nata (PRN) principle. Moreover, Conbercept exhibited a beneficial effect on blood flow status in the macula and facilitated the restoration of blood flow in areas where blood flow was previously absent [102].

While compared to laser photocoagulation, Liu K. et al. A treatment regimen of 0.5 mg conbercept administered as needed pro re nata (PRN) resulted in significant improvements in both the functional and anatomical outcomes of patients with center involved (DME) versus the results of laser photocoagulation [96] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of current available Anti-VEGFs for DME management.

| Drug | Manufacturer | Structure | Mechanism of action | Molecular weight | Year of approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brolucizumab | Beovu | Single chain antibody | Recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody VEGF inhibitor that binds to 3 major isoforms of VEGF-A suppressing endothelial cell proliferation, neovascularization, and vascular permeability. | 26 kDa |

Approved in 2019 for age related macular degeneration. Approved in 2022 for diabetic macula oedema |

| Bevacizumab |

Avastin Alymsys Mvasi Vegzelma Zirabev |

Monoclonal antibody | Binds to and neutralizes VEGF preventing its association with nuclear receptors, Flt-1 and KDR. | 149 kDa | Not approved for diabetic macula oedema |

| Faricimab | Vabysmo | Angiopoietin-2 Inhibitor |

Inhibits VEGF-A resulting in suppression of endothelial cell proliferation, neovascularization, and vascular permeability. Inhibition of angiopoietin-2 promotes vascular stability and desensitizes blood vessels to effects of VEGF-A. |

Approved in 2022 for age related macular degeneration and diabetic macular oedema | |

| Ranibizumab |

Byooviz Cimerli Lucentis Susvimo |

Antibody fragment | Binds to and inhibit VEGF-A suppressing neovascularization. | 48 kDa | Approved in 2006 for Macular Degeneration; Macular Edema; Diabetic Macular Edema; Diabetic Retinopathy; Myopic Choroidal Neovascularization. |

| Aflibercept | Eylea | Fusion protein | Decoy receptor for VEGF-A and placental growth factor (PlGF) inhibiting binding and activation of endothelial cell receptors thereby suppressing neovascularization. | 97-115 kDa | Approved in 2011 for neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration, macular edema following retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular edema, diabetic retinopathy, and retinopathy of prematurity. |

Steroids

Steroids are part of the management plans available for diabetic macular edema, especially for some patients who are unresponsive to other treatment modalities, such as anti-VEGF agents, like pregnant women and patients with recent strokes [103, 104]. About 40% of these patients don’t gain more than 5 letters, nor does their BCVA reach 20/40 [103]. Steroids mainly act by down-regulating the molecules and inflammatory mediators responsible for VEGF synthesis that partakes in the DME pathophysiology [103]. However, they still risk developing complications that render their use less preferred, such as developing cataracts and increased intraocular pressure “IOP.” [104] Steroids administered locally have proven to decrease intraocular inflammation, neovascularization and cellular proliferation [105], so now they are available as sub-tenon triamcinolone acetomide injections, and the newest promising advancement is dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implants, the latter has an effect lasting up to 3 years [7, 104]. However, as effective as literature reviews view them, they still carry an even higher risk of IOP, cataracts and poorer visual acuities than other treatment modalities. Hence, steroids are mostly reserved for non-responders who took 3 to 6 injections of anti-VEGF agents without improvement [7].

Current research suggests that combining anti-VEGFs with dexamethasone implant therapy can lead to reversing foveal damage and decreasing the need for injections [104, 106].

Injections of triamcinolone acetonide (TA)

Intravitreal injections of TA are mainly used as a safe short-term (< 3month) alternative when the patient is unresponsive to at least 3 doses of bevacizumab or when laser photocoagulation is contraindicated or unhelpful; many clinical studies found that there is a correlation between the dose of TA and treatment clinical outcomes, as higher doses (> 8 mg) appear to have a better chance at improving BCVA and increasing central retinal thickness (CRT). Nonetheless there.

No correlation was found between the dose of TA and the level of IOP elevation [7, 103, 105]. Doses > 13 mg have shown a longer-lasting overall effect and doses > 20 mg have shown a temporary improvement in visual acuity [105]. IOP is the most concerning complication of TA Intravitreal injections (IVTA); it is also the most commonest, affecting about 52% of 104 eyes 6 weeks into treatment. IVTAs also carry the risk of developing endophthalmitis and cataracts [105]. Sub-tenon injections of TA (STTA) seem to have a less effective impact on visual acuity and anatomic responses than their intravitreal counterparts (IVTA); however, these differences seem to be non-existent at the 6-month mark of treatment. Moreover, STTA has led to a higher increase in IOP than IVTA. Due to their short duration and need for multiple injections, they are not used as a monotherapy. They are usually used as an adjunct to anti-VEGF, leading to overall better results and fewer injections [7, 103]. IVTA has been shown to decrease micro-aneurysm number significantly in DME, So its use following anti-VEGF treatment might be beneficial in recurrent or persistent DME [107]. The newest approach being explored is suprachoroidal injections of TA (SCTA); higher doses up to 10 folds can be used with minimal drug infiltrating the anterior segment and lens; thus, a much lower rate of side effects has been observed. IOP increased significantly during the first month but then returned to baseline values at the 3-month mark with topical anti-glaucoma drops, which, in and of itself, is a superior aspect of SCTA over the other modalities of TA administration. Eyes with neurosurgery detachment and disruption of the inner/outer segments had the least favorable prognosis in BVCA improvement [108]. IOP increase appears to always negatively affect optic nerve morphology, even if treated with antihypertensive drugs or in the absence of intra-ocular hypertension [109].

Intravitreal sustained-release steroid implants

It is a 6-month sustained release implant which is mainly of 2 types; the first type is a non-biodegradable implant made of ethylene vinyl acetate containing a reservoir of the steroid needed such as TA; these implants require surgical implantation into pars plana, and the surgical explanation after drug reservoir is finished, which can lead to extra complications like retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage. Biodegradable types are mostly made of degradable polymers like Polylactic acid (PLA) and polyglycolic acid (PGA), so surgical removal is unnecessary. However, biodegradable types are not available with TA but rather with dexamethasone (DEX), rendering them superior to IVTA implants [105, 110].

DEX implants have shown a significant improvement in BVCA in treatment-naive patients and a substantial reduction in central macular thickness (CMT) 6 months following treatment.

However, only CMT seemed to improve in treatment-refractory patients, while BVCA remained unchanged significantly [111].

DEX implants are superior to IVTA implants because a much lower incidence of ocular hypertension and cataracts was reported using them than with IVTA implants in addition to fewer injections; the average was 1 injection with DEX implants, 1.44 for IVTA implants [110]. However, patients of both groups have improved vision and gained similar results of more than 10 letters along with CMT improvement as there were no significant differences between treatment groups at 6-month follow-up [110, 112]. Fluocinolone acetonide (FA) implants reach their peak efficacy 6 to 11 months post-injection most studies recorded 5 or more letters of improvement. Macular thickness and anatomical fluctuations were stabilized after FA injections, allowing for an enhanced visual acuity up to 3 years follow up [106]. DEX implants also appear to be superior to fluocinolone acetonide (FA) implants due to their lower risk of ocular hypertension and cataracts. However, FA implants tend to last much longer, up to 36 months, thus alleviating some of the treatment and visits burden, reducing the average treatment frequency from once every 3.2 months before FA implant administration to once every 16.7 months post-FA–FA implant. Additionally, about 25.5% of eyes remained free of any adjunctive treatment all through these 36 months [113, 114]. Lipid-based nanocarriers of TA are a novel approach showing promising results in the treatment of DME, Like an increase in foveal thickness, contrast sensitivity and VA. It can be used as an adjuvant or primary therapy and possibly be considered the future replacement of IVTA [105]. Response to extended-release steroid implants in the contralateral eye might occur in some patients, but the effect was mostly insignificant [115].

Systemic therapy

Although diabetic macular edema is treated mostly with laser photocoagulation and intravitreal anti-VEGF and corticosteroid injects, which are local therapies, systemic therapies have been implicated in previous research. These therapies could have a direct local effect on the retina or an indirect effect by affecting systemic parameters associated with diabetic macular edema. Some of the systemic parameters associated with diabetic macular edema are hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertension and the presence of coronary artery disease and heart failure [116–118].

Although inadequate control of diabetes is associated with the worsening of diabetic retinopathy and increased risk of diabetic macular edema, some of the antidiabetic drugs have no adverse effect on the risk and progression of diabetic macular edema. GLP-1 agonists are associated with a neutral effect regarding the risk of diabetic retinopathy and DME, except Semaglutide [119]. Glitazones and insulin are also associated with an increased risk of DME. However, causation should be further investigated as the association between these diseases and DME could be confounded by type 2 diabetes disease increased activity requiring the administration of the drugs [120–122]. However, the adverse effects of glitazones could be explained by increased water retention, and the cessation of these drugs was associated with an improvement in DME after 3 months in a group of patients [123]. Biguanides (Metformin) and SGLT-2 inhibitors were associated with a lower risk of DME. However, there is still a need for randomized controlled trials examining the effects of these drugs on DME progression and risk [124, 125]. Metformin and SGLT-2 inhibitors are suggested to have local effects, with SGLT-2 inhibitors acting on SGLT-2 receptors found in the retina, Metformin affecting the expression and splicing of VEGF [7]. DPP-4 inhibitors were not associated with an increased risk of DME [126]. The effect of the previously mentioned antidiabetic drugs and other antidiabetics should be further investigated [5].

Lipid-lowering drugs were shown to have a positive effect on DME. Statins were shown to be associated with a lower risk of DME, although they do not affect diabetic retinopathy progression [127]. Two randomized controlled trials of fibrates lowered the risk of diabetic retinopathy and DME [7]. In a systematic review, fibrates, but not statins, were shown to reduce the risk of DME, but the evidence is of low certainty [128]. A newer study showed that fibrates were associated with a lower risk of diabetic retinopathy but not DME [129]. Thus, further studies are needed to examine the effects of lipid-lowering drugs on DME risk and progression.

Other systemic therapies potentially managing DME include infliximab, an anti-TNF biologic. Although intravitreal infliximab was ineffective in preclinical trials and trials on a small number of patients and caused adverse effects of uveitis, a randomized controlled trial using systemic infliximab for refractory DME patients showed that infliximab was well tolerated and effective in improving visual acuity [130–132].

Oxygen therapy was shown to be effective for DME, with one randomized controlled trial with a face mask on the oxygen flow rate of 10 L/min leading to improvement in Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiogram and electroretinograms findings [133]. Another more recent prospective study showed improvement in diabetic retinopathy and DME with hyperbaric oxygen therapy [134]. A study done on patients being treated for the diabetic foot with hyperbaric oxygen therapy showed no long-term effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on diabetic retinopathy or DME; however, the study aimed to detect any harmful ophthalmological impact of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in diabetic foot patients [135].

Laser therapy

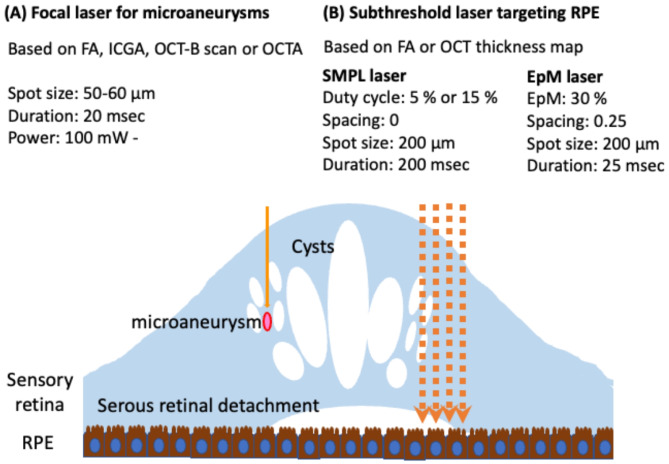

Laser therapy targets retinal tissue with light absorbed by the ocular pigment, most commonly in the retina, choroid, melanin, and hemoglobin [136]. The exact mechanism of action is unknown, but one of the theories suggests that light from laser therapy destroys tissue, so less oxygen reaches the target, it gets hypoperfused, and the remaining tissues get hyperperfused. Current laser therapies have many various types and settings (see Fig. 3) [137].

Fig. 3.

The summary includes the types and parameters of current laser therapies. (A) When focusing on microaneurysms with focal laser treatment (indicated by a solid orange arrow), it is advisable to apply the laser for a short duration. To plan the laser treatment, images from fluorescein angiography (FA), indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), optical coherence tomography (OCT) B-scan, or OCT angiography (OCTA) would be utilized. (B) Subthreshold laser treatment (indicated by an orange dotted arrow) is aimed at the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

Conventional laser therapy has been used for decades in treating macular edema and has shown clinical significance in reducing the thickening of the retina in two ways (focal or diffuse) [138]. However, burning the area around the retina has an adverse effect, which causes atrophy, scarring, scotoma, and fibrosis [139–141].

After that, the modified laser therapy was invented to reduce the adverse effect because it was less intense, had a smaller spot size, and affected a small area, so it modified the thickness, which contains a small area of the retina and the non-perfusion area [1, 142].

Then, modern laser therapy evolved, containing both the therapeutic effect of conventional and the less adverse effect of modified laser therapy. the semi-automated pattern scanning retinal photocoagulation system (PASCAL®, PAttern SCAn Laser) [143] which contains multiple burns(4–65). A 532-nm wavelength is utilized through a standard slit-lamp system in a specific pattern (grid, arc, etc.). It shows some advantages such as less time, more comfort for the patient, and more accuracy, which avoids making a scar that results in a scotoma. Some studies said that less time of laser reduces the time of burning the retina and more comfort for the patient because less time heating the choroid [144].

Pattern scan laser is highly efficient in treating Diabetic macular edema (DME). It consists of ring and arc patterns with a central foveal exclusion zone. It differs from conventional laser therapy (mentioned above) in that no burn is placed close to the center of the foveal avascular zone. Pattern scan is also used in subthreshold laser [145, 146].

Further, Selective Retinal therapy (SRT) is characterized by 30 pulses ranging from 450 to 800 mJ/cm2 per pulse [158, 159] and a high temperature that targets melanosomes inside retinal pigment epithelium which absorb 50% of green light. There are two types: pulse and continuous wave scanning mode. There are a lot of clinical trials that showed the safety and effectiveness of SRT. For example, a retrospective showed significant effectiveness in the visual accuracy of SRT for 6 months with follow-up up, and there was no adverse effect; however, SRT was not clinically used because it didn’t show any retinal changes and unidentified energy needed for therapeutic damage, so it is challenging to use it clinically [73].

Moreover, Subthreshold Diode Micropulse Laser (SDML) was first described for DME in 1997 by Karatza and Fiberg [160]. Since then, several RCTs have shown that SDML is more effective or the same as conventional laser grid therapy. Laursen et al. [161] performed the first RCT in 2004, comparing 810 nm SDML to conventional argon 512 nm laser therapy. This resulted in the same visual acuity, but better thickness SDML was received typically using a longer duration than other studies, which may have made it more successful. In 2009, Figuiera et al. [162] performed a similar study where eyes were treated at baseline and for 4 months if edema persisted. They found no change in visual acuity thickness and contrast sensitivity. Still, they recorded 59% of scars in eyes treated with conventional and 14% with SDML, showing fewer adverse effects. Still, the same effectiveness showed more burn in eyes treated with SDLM than conventional, suggesting that the laser used in SDML led to overtreatment where suggested undertreatment in the traditional group.

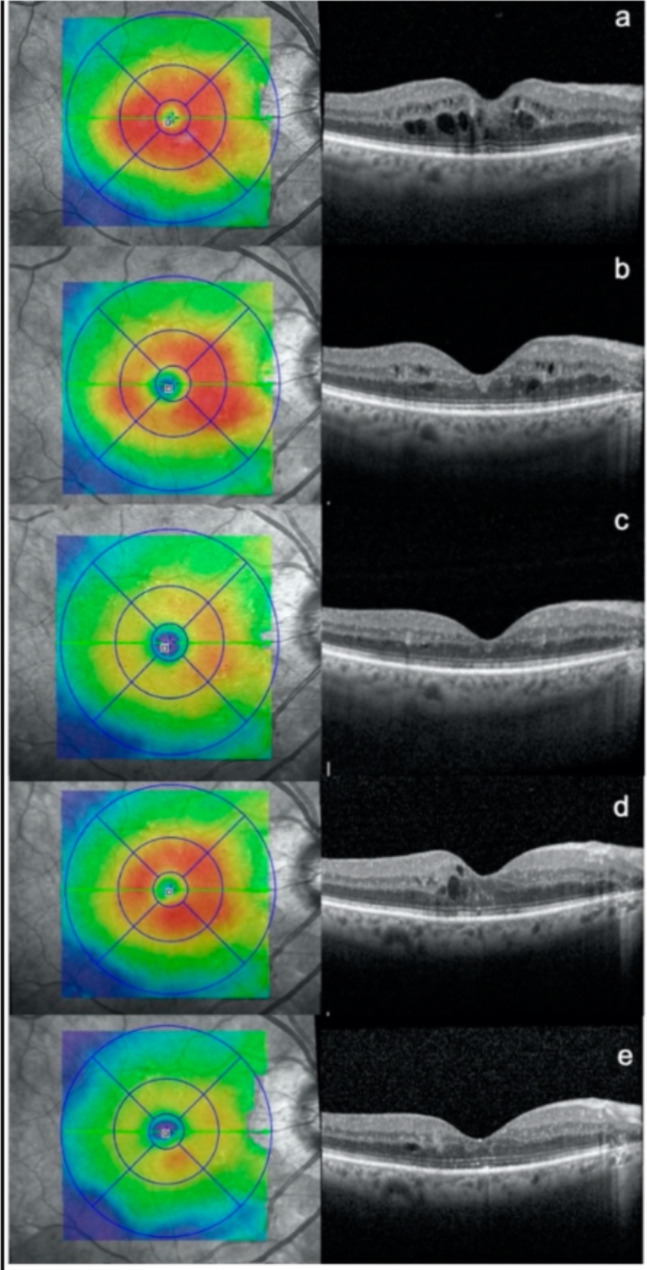

Another study by Lavinsky in 2011 [147] compared focal laser to normal and high-density SDML and hypothesized that a larger area and less damage effect of SDML is superior to the conventional grid. They were treated at baseline, 6 and 12 months, and they yielded that high-density SDML showed more visual acuity at 12 months, but average density showed no improvement in visual acuity. Macular thickness was the same between all groups, so the result showed that high-density SDML is superior to the other two treatments. Other additional studies compared the previous outcome in addition to electro and psychological and showed no difference, the same as previous studies (see Fig. 4) [148]. In addition, Venkatesh showed fewer signal voids 4/23 in patients treated with SDML than 18/23 in conventional patients, resulting in superior treatment because of the preservation of electro-physical function [147]. Furthermore, Vujosevic et al. [149] have shown an increased significant difference in mean central retinal sensitivity while decreased in conventional. There is a lot more RCT showing the benefaction usage of SDML in the treatment of DME [7, 147]. What makes Subthreshold Diode Micropulse Laser (SDM) unique is that it is a continuous sequence of repetitive short pulses with a long break between them. Hence, the benefit of an extended break is that it can help the retina cool down and avoid burn. It works by stimulating retinal pigment epithelium directly because no damage to the retina occurs, making it work on a large area. SDM showed not only inferiority to the standard but also equivalent to it [150].

Fig. 4.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans were taken of a patient with diabetic macular edema at different time points: (a) before any treatment, (b) 3 months after the first subthreshold micropulse macular laser (SMPL) treatment, (c) 3 months after the second SMPL treatment, (d) an additional 3 months after the second SMPL treatment, and (e) 3 months after the third SMPL treatment.

Pars plana vitrectomy

Pars Plana vitrectomy (PPV) is a surgical approach primarily utilized in treating tractional DME in patients with poor response to medical therapy. PPV is a procedure that aims to remove the glycation end products and tractional elements superimposed by diabetes retinopathy, which plays a vital role in the development of macular edema [151, 152]. Results were statistically significant for sub-foveal choroidal thickness (SCT) at 6 months post-operatively and for central macular thickness (CMT) at the 1st, 3rd and 6th month following the operation. VA improved significantly in the 3rd and 6th months after surgery [151]. PPV has also been performed in non-tractional macular edema; despite its controversy, significant anatomical improvement has been reported up to 2 years following surgery. However, visual improvement, although reported to improve in some literature, was not a consistent result. It has been speculated that the mechanism by which PPV improves anatomical and sometimes visual outcomes in DME is increased oxygen and capillary blood delivery to the retina, suppressing VEGF production [152]. The other theory is that PPV removes subtle, unnoticeable tractions and increases the clearance of VEGF [153]. PPV, when paired with the internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling, didn’t demonstrate any significant differences in the anatomical and functional results in comparison to PPV alone; some researchers also believe that ILM peeling could cause additional unnecessary retinal damage, which has led to multiple reported cases to delayed recovery and improvement in BVCA and CMT when compared to their PPV only counterparts [154].

Current studies are exploring the potential benefits and possible outcomes of performing PPV in combination with ILM peeling on treatment-naive eyes with DME instead of eyes with refractory and persistent DME to study the efficacy of PPV without having to deal with the setbacks of irreversible retinal damage due to the condition itself and repeated intravitreal injections [155]. PPV performed for reasons other than diabetic retinopathy has been documented.

in literature to have a protective role against the disease evolution and future complications in.

In addition to slowing down its course [153].

Another study investigated the effect of intentionally inducing macular detachment while performing PPV. Results revealed a significantly faster and more significant reduction of CMT at the 1st, 2nd and 4th week, but results were insignificant at the 12th and 24th week of the study. BVCA and morphological outcomes were similar to patients who underwent PPV only [156]. PPV paired with ILM peeling in the presence of dexamethasone intra-vitreal implant did appear to prolong the effect of DEX implants with subsequent prolongation of the time usually needed for macular edema to recur. However, no added benefits or differences were observed in the functional and anatomical results of vitrectomized and non-vitrectomized eyes [157].

Combined therapy

Anti-VEGF only vs. anti-VEGF with subthreshold diode micropulse laser

Intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF is a better therapy compared to laser therapy; however, it costs over 100,000 dollars annually and needs the patient to follow the physician’s prescription accurately [73]. Laser therapy shows slower onset but longer acting, costing much less. The newer types of it, like subthreshold, showed fewer side effects, so that’s what makes it better to combine with anti-VEGF therapy and the aim of combining to give less injection with the same outcome. Anti-VEGF plus laser showed the best visual acuity outcome at 6 and 12 months; however, anti-VEGF only showed better macular thickness outcomes at 12 months. Combined, no significant difference in macular thickness was observed at 6 months [158].

There are some side effects of monotherapy, such as anxiety, pain after injection, and retinal detachment, so the reason further research needs to be established at the same time with central macular thickness of more than 400 μm anti-VEGF needed because subthreshold therapy works only on less than 400 μm. However, the addition of SDM didn’t improve outcomes, but fewer injections were required, so it cost less and fewer visits were needed [73, 158, 159]. However, further studies are necessary to show the cost-effectiveness and side effects of combining.

Intravitreal triamcinolone plus macular laser photocoagulation

Intravitreal Triamcinolone (IVT) is an anti-inflammatory steroid. Randomized clinical trial comparing IVT after MLP or IVT only. It showed a significant decrease in visual acuity more than IVT only, and the combination maintained was reduced 3 months after therapy; however, 40% of the intraocular pressure increased in both groups [150]. However, combined therapy was not superior to IVT alone but had a better effect than laser alone [160].

Ranibizumab (Anti-VEGF) plus macular laser photocoagulation

Ranibizumab conducted more improvement in visual acuity than MLP only or MLP with Ranibizumab at 6 months but showed no significant difference at 2 years. Ranibizumab showed a decrease in foveal thickness at 6 months; then, foveal thickness increased in the subsequent follow-up. This is in contrast to Combined therapy, which showed a reduction in thickness during 24 months. The additional MLP showed improvement. Also, fewer injections of Ranibizumab are needed, so it costs much less than Ranibizumab only. Also, combined therapy reduced intraocular pressure and injection, so less drug use [61, 161].

Ranibizumab plus dexamethasone

it shows improvement in visual acuity and macular thickness, which significantly reduced at 1 month, and there is a positive correlation after the first injection; however, in a later stage, the outcome is reduced. It is mainly used before irreversible change in the macula because it has a good effect at an early stage. Other treatments showed irreversible changes in the macula because damage had already occurred to the macula [162].

Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (IVB) plus focal macular photocoagulation (FMP) therapy

An RCT was conducted at Liaquat University. Between 2019 and 2022, two groups of 130-patient were assigned to receive intravetrial bevacizumab (IVB) alone and IVB plus focal macular photocoagulation (FMP) combination therapy over 3 months with a monthly follow-up for both of the groups. The BCVA was evaluated at the end of the 3 months, and the outcome was that the combined IVB plus FMP treatment showed a superior visual outcome compared to the monotherapy [163].

Intravitreal injection of Conbercept (IVC) plus macular pulse laser (MPL) therapy

The combined therapy of IVC + laser therapy revealed a better response rate at curing DME due to the role of Laser therapy in repairing the blood-retinal barrier [164]. On the other hand, it may cause damage to capillaries, which would increase thickness and vision loss and reduce the effect over a long time. That’s why we combine it with IVC: because it has a better effect with more extended time, and multiple targets also reduce VEGF and inhibit inflammation, edema, and exudation, thus improving visual acuity. Studies showed that visual acuity and macular thickness were better combined than IVC alone, which proves the result of Qiao et al. [165].

After analysis, there is a lower visual field gray value and visual field defect, and the patient’s light threshold sensitivity to light was a 30° field of view higher. Also, combined therapy showed improvement in the quality of the visual field, and this is due to MPL causing less scaring and less production of coagulation of protein and fewer injections in 6 months, thus reducing drug use [164].

Intravitreal injection of conbercept (IVC) plus laser photocoagulation therapy

In a comparative study, Zhan H. et al. found that an observation group (conbercept + laser photocoagulation) had a significantly higher total efficacy rate (93.85%) than the control group (laser photocoagulation only) (78.46%). BCVA, retinal thickness, and central macular thickness improved in the combined group. Both groups showed improved levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, interleukin-6, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and essential fibroblast growth factor after treatment, with the combined group exceeding the control group (P < 0.05). Concluding that combined laser photocoagulation and IVR conbercept for DME improve vision and lower intraocular cytokine levels more effectively and safely [166].

Promising therapeutics and futuristic insights for DME management

Although efficacious therapies for Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) are extant, many studies have elucidated that the outcomes in pragmatic settings do not align with the superior results in controlled clinical trials [167]. A contributing factor to this divergence could be attributed to the onerous regimen imposed by extant therapies, which may precipitate less than optimal adherence to treatment protocols, culminating in inadequate management of the condition. Furthermore, some patients may demonstrate partial therapeutic responses despite treatment adherence. These issues underscore the need for therapeutics with enhanced efficacy and prolonged durability. Subsequently, an overview of promising therapeutic advances and insights is discussed.

Photobiomodulation therapy

Low-level light is used in photobiomodulation therapy (PBM), a non-invasive treatment, to promote tissue repair and activate biological processes. PBM functions through a photochemical process in which light is taken up by chromophores found within the cells, like the mitochondria’s cytochrome c oxidase (CCO). This increases mitochondrial activity, ATP synthesis, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulation. In addition to their potential to inflict oxidative damage on biological components, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are crucial for signaling and homeostasis. PBM can affect ROS levels differently based on the amount, type, and length of light exposure. By boosting the activity of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), low dosages of PBM can lower ROS levels and catalase by enhancing the repair of oxidative damage [168]. High doses of PBM can raise ROS levels by promoting the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). These molecules can then activate different signaling pathways, including nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and cause cellular responses, including inflammation, proliferation, and apoptosis [169]. DME is a common consequence of diabetes that results in swelling and fluid leaking in the central retina, ultimately leading to vision loss. PBM has been suggested as a viable therapy for DME. Intravitreal injections of corticosteroids or anti-VEGF medications are typically used to treat DME. Still, these treatments have several drawbacks, including high cost, frequent injection requirements, and infection risk. PBM works by increasing mitochondrial activity, decreasing oxidative stress, and regulating inflammation in the retinal cells to improve retinal function and reduce vascular leakage. Numerous preclinical and clinical investigations have examined PBM’s impact on DME. PBM administered via a retinal laser or light-emitting diode (LED) device has been demonstrated in animal models to shield Müller cells and photoreceptors from harm., increase mitochondrial membrane potential, and decrease retinal vascular leakage induced by Müller cell disruption [170, 171] (see Fig. 5) [170].

Fig. 5.

Mechanism of action in laser photobiomodulation.

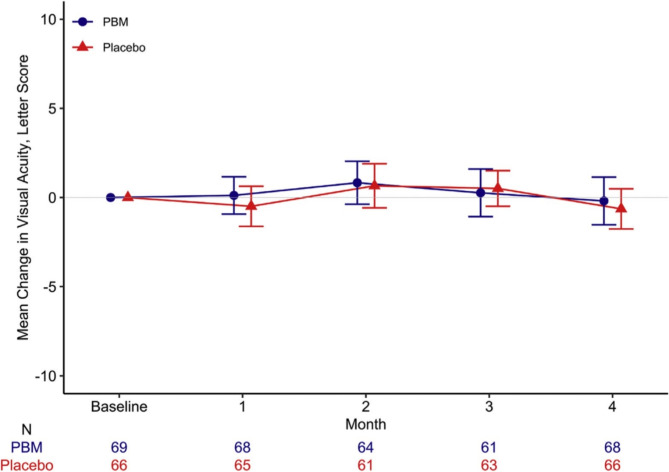

In human trials, PBM delivered by an LED eye patch or a retinal laser has been tested in patients with center-involved DME and good visual acuity. In a phase 2 randomized clinical trial by Kim et al. [187], 135 patients were compared with PBM eye patches and placebos, and at 4 months, there was no discernible change in either central subfield thickness (CST) or visual acuity (VA) (see Fig. 6). PBM retinal laser was used in 21 patients in a phase 2a open-label dose-escalation trial by Shen et al. The results showed a substantial decrease in CST at 2 and 6 months but no significant change in VA [172]. From April 2019 to February 2020, a study randomly assigned 135 adults to PBM (n = 69) or placebo (n = 66). The median age of the participants was 62 years, with 37% being women and 82% identifying as White. The PBM group showed a median device compliance of 92%, while the placebo group had 95% compliance. Over the 4 months, OCT CST (central subfield thickness) increased by a mean (SD) of 13 (53) µm in PBM eyes and 15 (57) µm in placebo eyes, resulting in a mean difference (95% confidence interval [CI]) of − 2 (− 20 to 16) µm (P = 0.84).CI-DME (center-involved diabetic macular edema) was identified in 90% of PBM eyes and 86% of placebo eyes at the 4-month mark, based on DRCR Retina Network sex- and machine-based thresholds. The adjusted odds ratio for CI-DME was 1.30 (95% CI: 0.44–3.83; P = 0.63). Visual acuity (VA) experienced a mean (SD) decrease of − 0.2 (5.5) letters in the PBM group and − 0.6 (4.6) letters in the placebo group, with a difference (95% CI) of 0.4 (− 1.3 to 2.0) letters (P = 0.64). Regarding safety, there were 8 adverse events potentially related to the PBM device and 2 to the placebo device. Fortunately, none of these events were classified as severe [173]. The findings of these investigations indicate that PBM may help individuals with DME by lowering macular edema but not by improving eyesight. However, the data is restricted by the lack of defined outcome measures, short follow-up period, heterogeneity of PBM parameters, and small sample size. Larger, more thorough trials are required to confirm PBM’s safety and effectiveness for DME and to improve the treatment plan.

Fig. 6.

The average difference in visual clarity (with 95% confidence intervals) between the start and 4 months into a preliminary investigation of photobiomodulation (PBM) treatment for diabetic macular edema (Protocol AE).

Tarcocimab tedromer (KSI-301, kodiak sciences)

A novel intravitreal anti-VEGF, is being evaluated and developed for treating diabetic macular edema. Tarcocimab tedromer has been developed as a novel approach to VEGF inhibition by acting as an antibody biopolymer conjugate. The molecular size had been enlarged to 950 kDa by attaching the IgG1 VEGF antibody portion to a large biopolymer to prolong the intravitreal residence time [103, 174]. The ocular tissue half-life for both retina and choroid for Tarcocimab tedromer is more than 10.5 days and 12.5 days, respectively, as has been shown in rabbit models [175, 176]. The GLEAM and GLIMMER studies are identically designed, randomized, double-masked, active comparator-controlled studies for evaluating the efficacy, durability and safety of tarcocimab tedromer in 460 and 457 treatment-naïve subjects with diabetic macular edema, respectively. However, high proportions of patients on meaningfully longer treatment intervals were observed with tarcocimab tedromer, with half of the patients on every 24-week dosing at the primary endpoint. The primary efficacy endpoints of the GLEAM and GLIMMER studies were to show the non-inferiority of tarcocimab tedromer (dosed every 8 to 24 weeks after 3 months of loading doses) in comparison to aflibercept (given every 8 weeks after 5 months of loading doses) for visual acuity gains. The two studies did not meet these primary efficacy endpoints; However, an increase in adverse effects was observed during the studies in which cases of cataracts were reported using tarcocimab tedromer. Thus, Kodiak’s initial evaluation suggests the failure of both studies and a decision to discontinue further development of Tarcocimab tedromer (KSI-301) was made [177].

OPT-302 (sozinibercept, opthea)

Represents an investigational soluble fusion protein that targets two growth factors, VEGF-C and VEGF-D, diverging from conventional anti-VEGF agents which solely inhibit VEGF-A and VEGF-B. The scientific consensus posits that adjunctive therapy with OPT-302 in conjunction with established anti-VEGF treatments may confer augmented and sustained therapeutic outcomes for individuals afflicted with Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) relative to monotherapy [178]. In a cohort of DME patients previously administered aflibercept, the phase 2a trials conducted by Opthea revealed that the visual acuity in subjects receiving a combination regimen of OPT-302 and aflibercept exhibited an average enhancement of 6.6 letters at the 12-week mark, in contrast to a 3.4-letter improvement observed in the monotherapy group [179]. Moreover, 27% of the combination therapy group experienced a visual acuity gain of 10 letters or more, a significant contrast to the absence of such improvement in the aflibercept-alone cohort. Notably, OPT-302 was associated with minimal adverse effects in these initial studies. Presently, OPT-302 is under scrutiny in the phase 3 SHORE and COAST trials, targeting the management of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [180].

MYL-1701P (momenta pharmaceuticals and mylan)

A novel drug that inhibits the activity of two proteins involved in abnormal blood vessel growth: placental growth factor (PEGF) and VEGF-A. It is a potential substitute for Eylea, a current treatment for diabetic macular edema (DME) [78]. In October 2021, a research team conducted a phase 3 trial to compare the safety and effectiveness of MYL-1701P and Eylea in 324 patients with DME. The patients received the drug until week 48 of the study [78].

CT-P42 (celltrion)

A recently manufactured drug administered via intravitreal injection to treat DME and AMD. It effectively inhibits the activity of PGF, VEGF-A, and VEGF-B. The drug showed good tolerability in a trial involving about 200 patients with DME, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS). So far, this drug has yet to be approved by the FDA, despite its high expectations, especially after the completion of the phase 3 trial in February 2021, which evaluated its efficacy and safety compared with Eylea [181].

IBI_324 (innovent biologics)

A drug that targets Ang 2 (Angiopoietin-2) and VEGF-A and inhibits both for patients with DME. The drug has two main strategies to inhibit the formation of abnormal neovascularization: The N-terminal blocks the signaling pathways mediated by VEGF-A, and the C-terminal prevents the binding of Ang 2 to the Tie 2 receptor. The manufacturer presented the key points about the drug, including the phase 1 trial’s evaluation, which covered the efficacy, safety and tolerability. No undesirable ocular side effects occurred even when the maximum dose of 4 mg was administered in the trial [182, 183]. In the SAD phase, a notable response was observed in both BCVA and CST up to day 42 after the dose of each treatment group. In the MAD phase, after one month of the third dose, a clear improvement in the baseline of BCVA was observed by 6.7 ± 5.4 letters in the group with the 2 mg dose and 7.7 ± 4.7 letters in the group with the 4 mg dose of the drug [182, 183].

OCS-01 eye drop (oculis SA)

A topical corticosteroid with a potential alternative to the more invasive intravitreal steroid injections. In a phase 2 clinical trial, subjects administered with OCS-01 manifested a substantial diminution in central macular thickness, recording a mean reduction of − 53.6 μm, as opposed to a − 16.8 μm reduction in the placebo cohort, over 12 weeks [184]. Despite these promising results, OCS-01 did not correlate with a marked enhancement in visual acuity (VA). The compound was predominantly well-received, although there was a notable incidence of elevated IOP among certain participants. Meanwhile, a phase 3 trial DIAMOND study is ongoing. Preliminary findings indicate a significant improvement in visual acuity for DME patients treated with OCS-01, with gains of + 7.2 letters at 6 and 12 weeks, compared to + 3.1 letters in the placebo group [185].

Genentech’s port delivery system (PDS) with ranibizumab

A surgically implanted device already approved for treating wet AMD. It administers an intravitreal dose of a concentrated ranibizumab formulation (100 mg/mL). The primary endpoint was met in the PAGODA phase 3 trial, which randomized 634 DME patients to receive monthly ranibizumab or PDS with refill exchanges every six months. The best-corrected visual acuity averaged over weeks 60 and 64 was comparable between the two arms. Furthermore, PDS was well tolerated; over 95% of patients did not need any additional treatments during the two refill cycles that were required in between required refill exchanges [186]. Notably, PDS was voluntarily recalled in October 2022 because of safety concerns about septum dislodgment; however, it is now back on the market [187].

Gene therapy

A single treatment could remove the need for painful, repetitive, and frequent injections, making gene therapy an appealing option for treating retinal diseases. The modified adeno-associated vector 2–2-associated intravitreal gene therapy known as ADVM-022 (Adverum Biotechnologies) encodes for a chemical akin to aflibercept, which was being investigated for DME in the INFINITY phase 2 trial. The outcomes demonstrated anatomical and optical efficacy and a noteworthy decrease in treatment load compared to pretreatment. However, safety concerns—specifically, intraocular inflammation and hypotony, which caused considerable vision loss in some—led to the suspension of the trial [188, 189].

Another intriguing intravitreal gene treatment is called 4D-150 (4D Molecular Therapeutics). It delivers a transgene encoding for aflibercept and a VEGF-C RNAi, efficiently blocking VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and PlGF (placental growth factor) through a proprietary R100 vector. In treating wet AMD, the phase 1 PRISM study demonstrated a favorable safety profile for 4D-150; the phase 2 SPECTRA trial currently enrolls patients with DME [190].

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

TKIs block angiogenesis-related pathways intracellularly, potentially providing a novel means of treating DME. An oral version of the TKI imatinib [191], YD-312 (YD Global Life Sciences Co, Ltd.), was first created to treat chronic myeloid leukemia. When YD-312 was compared to placebo therapy, phase 2a testing revealed a significant improvement in baseline visual acuity. Phase 2b testing is what [192] YD Global Life Sciences Co., Ltd. intends to move on to. Another TKI, EYP-1901 (EyePoint Pharmaceuticals), delivers vorolanib via a bioerodible delivery system that may provide up to a six-month shelf life. There were no noteworthy safety concerns during EYP-1901 treatment, according to the phase 1 DAVIO trial [193]. A study that examined the care of individuals with DME was initiated in early 2024.

Kallikrein-kinin (KK) inhibitors

Studies have shown that kallikrein levels are approximately 11 times higher in patients with DME compared with healthy subjects, suggesting that blockage of kallikrein may slow DME progression, specifically by limiting retinal permeability [73, 194]. THR-149 (Oxurion NV, Leuven, Belgium) is a bicyclic peptide inhibitor of human plasma kallikrein. A phase 1, open-label, multicenter dose-escalation study with 3-month follow-up evaluated the safety and efficacy of a single intravitreal injection of THR-149 at three dose levels (5, 22, 130 µg) in 12 DME patients [195, 196]. All subjects completed the study, and no serious adverse events were recorded. By the third month, there was a mean change from Baseline BCVA of + 7.5 letters on Day 14 and + 6.4 letters. The average CST change from baseline at month 3 was + 30.0 μm.