Abstract

Objectives:

To explore the predictive performance on the need for surgical intervention in patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO) using machine-learning (ML) algorithms and investigate the optimal timing for transition to surgery.

Methods:

One hundred and six patients with ASBO who initially underwent long transnasal intestinal tube (LT) decompression were enrolled in this retrospective study. Traditional logistic regression analysis and ML algorithms were used to evaluate the risk of need for surgical intervention.

Results:

Non-operative management (NOM) by LT decompression failed in 28 patients (26%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified a drainage volume ≥665 ml via LT on day 1, interval between ASBO diagnosis and LT intubation, and small bowel dilatation at 48 h after LT intubation to be independent predictors of transition to surgery (odds ratios 7.10, 1.42, and 19.81, respectively; 95% confidence intervals 1.63-30.94, 1.00-2.02, and 3.04-129.10; P-values 0.009, 0.047, and 0.002). The random forest algorithm showed the best predictive performance of five ML algorithms tested, with an area under the curve of 0.889, accuracy of 0.864, and precision of 0.667 in the test set. 97.4% of patients without transition to surgery (n=78) had passes of first flatus until three days.

Conclusions:

This is the first study to demonstrate that ML algorithm can predict the need for surgery in patients with ASBO. The guideline recommended period for initial NOM of 72 h seems to be reasonable. These findings can be used to develop a framework for earlier clinical decision-making in these patients.

Keywords: adhesive small bowel obstruction, long transnasal intestinal tube, machine-learning, non-operative management, surgery

Introduction

Postoperative complications are associated with increased morbidity and medical costs, and adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO) is a common complication after abdominal surgery and a common cause of surgical emergencies[1,2]. ASBO can cause considerable harm, requiring eight days of hospitalization on average with an in-hospital mortality rate of 3% per episode[3-6]. The management strategy for ASBO varies widely according to era, country, institution, and the personal preferences of surgeons. Immediate surgical intervention has traditionally been the mainstay of treatment for patients with ASBO[7,8]. However, previous studies have demonstrated that non-operative management (NOM) is effective in approximately 70% of these patients[6,9]. The 2018 Bologna guideline[10] strongly recommends initial NOM until 72 h for patients with ASBO, who had no signs that require emergent surgical exploration (i.e., to peritonitis, strangulation or bowel ischemia). NOM for ABSO consists of fasting, intravenous fluids, and gastrointestinal decompression using a nasogastric tube (NGT) and/or a long transnasal intestinal tube (LT). Approximately 30% of patients with ASBO who are initially treated by NOM, particularly an LT, ultimately require surgical intervention[11-13]. Delayed surgical intervention have been associated with increased morbidity, mortality, a prolonged hospital stay, and increased medical costs[14-17]. Furthermore, the 72-h period of NOM recommended by the guideline[10] is not evidence-based. Therefore, it is clinically important to be able to identify predictors of failure of LT decompression and the optimal timing for transition to surgery to minimize the risk of delayed surgery in patients who require it and avoid an unnecessary medical burden.

The recent advent of machine learning (ML) has led to innovations in various fields. The methodology used in ML allows predictions to be made based on existing data. Moreover, the accuracy of prediction is better with an ML algorithm than with conventional regression models. ML has an important role in analysis of complex medical data and has demonstrated its superiority in studies based on omics, electronic health records, and image processing[18-20]. However, few researchers have investigated ASBO and the limited literature available tends to focus on radiological diagnosis[21,22]. Therefore, in this study, we sought to identify predictors of the need for surgical intervention after NOM by building ML models and its optimal timing in a retrospective cohort of patients with ASBO.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 106 patients with ASBO who were treated by LT decompression between September 2011 and August 2016 in the Department of Surgery at Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital. ASBO was diagnosed on the CT images if the images showed a dilated small bowel and if there were clinical symptoms of nausea, vomiting, or abdominal fulness present. In our department, the first step in NOM for patients with ASBO is decompression with a 12 or 16 Fr NGT (Salem Sump™, Coviden, Tokyo, Japan) or 18 Fr LT, continuously suctioned with negative pressure of 10 cmH2O, (ClinyⓇ, Create Medic, Tokyo, Japan). If NGT decompression is ineffective at around 48 h after intubation, the NGT is replaced with an LT to improve the efficacy of decompression. We initially introduced LT for decompression in patients with severe abdominal fullness and/or severe radiological findings, such as an intense degree of width and range of small intestinal dilatation. For intubation using an LT, 50 ml of water-soluble contrast agent (WSCA; GastrografinⓇ, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) are administered via a catheter to confirm the position of the tip of the LT. Surgical intervention for patients who have failed on NOM is planned for around seven days after intubation.

The inclusion criteria in this study were age ≥20 years, previous history of laparotomy, ASBO diagnosed by abdominal computed tomography, and LT decompression. The following exclusion criteria were applied: need for surgery because of suspected strangulation or perforation, recurrence of ASBO within 30 days of laparotomy, and inflammatory bowel disease, mesenteric vascular disease, suggestive of non-adhesive etiologies such as paralytic ileus, fecal impaction, peritoneal carcinomatosis, incarcerated hernia. Attending surgeons determined the indication for surgical intervention based on clinical and radiological findings and a constant drainage volume.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital (approval number: 522) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for written informed consent was waived in view of the retrospective nature of the research.

Data collection

Clinical characteristics, laboratory data on admission, and radiologic findings over time were retrieved from the medical records. Information was collected on age, sex, date of diagnosis of ASBO, date of LT intubation, date and type of any previous laparotomic procedures, surgical history, number of recurrences of ASBO, comorbidities, drainage volume on day 1 after LT intubation, white blood cell count, creatine phosphokinase and C-reactive protein levels, ascites, passage of WSCA through the colon at 48 h, and dilatation of the small intestine (normal, 4 cm[23]) at 48 h after LT intubation assessed by radiography or CT, passes of first flatus, and if so, the date.

Analysis of data

Continuous data are expressed as the median with interquartile range. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Discrete variables were compared using the chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. To identify risk factors for transition to surgical intervention, multivariate logistic regression analyses were applied using variables that were statistically significant in univariate analysis and had a P-value <0.1. The statistical analyses were performed using BellCurve for Excel (Social Survey Research Information, Tokyo, Japan). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Python software version 3.8 was used for statistical testing and computing ML methods. The study population was randomly divided into a training set and a test set in a ratio of 8:2. The prediction model was established by creating a training set and then applying the trained model to the test set for prediction. Five algorithms, namely, decision tree, random forest, gradient boosting, naïve Bayes, and logistic regression, were used to evaluate the likelihood of risk of transition to surgical intervention. The prediction model was developed based on the ML algorithm with the best performance, which was determined by the area under the curve (AUC). If the AUC is greater than 0.9, then it is considered to have excellent predictive power in the model.

Results

The patient demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. NOM with LT decompression was successful in 78 patients (74%) and failed (i.e., transition to surgical intervention was required) in 28 (26%). Body mass index was significantly lower in the surgery group than in the non-surgery group (P=0.033). Previous operations for non-inflammatory and malignant disease were more common in the surgery group than in the non-surgery group; however, the between-group differences were not statistically significant (P=0.085 and P=0.083, respectively). A history of surgery via a laparoscopic approach was significantly more common in the surgery group (P=0.041). The number of previous surgeries and number of occurrences of ASBO were comparable between the study groups, as was the rate of bridging from NGT to LT intubation. The interval between diagnosis of ASBO and LT intubation was significantly longer and the drainage volume via the LT on day 1 was significantly greater in the surgery group than in the non-surgery group (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). The rate of passage of WSCA into the colon at 48 h was significantly lower and the rate of small intestinal dilation at 48 h after LT intubation was significantly higher in the surgery group (P=0.020 and P<0.001, respectively). The median interval between LT intubation and surgical intervention was 7.0 days in the surgery group. There was a significant between-group difference in the total length of hospital stay.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of ASBO Patients (n=106).

| Variables | Non-operative group (n=78) | Operative group (n=28) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient backgrounds | |||

| Age (years)a | 68 (59-78) | 70 (60-76) | 0.829 |

| Sex (male:female) (%) | 48 (61.5):30 (38.5) | 16 (57.1):12 (42.9) | 0.748 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 21.6 (19.0-23.9) | 20.1 (17.9-21.6) | 0.033 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Cardiovascular diseases (yes:no) (%) | 11 (14.1):67 (85.9) | 1 (3.5):27 (96.4) | 0.176 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases (yes:no) (%) | 6 (7.7):72 (92.3) | 1 (3.5):27 (96.4) | 0.673 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes:no) (%) | 12 (15.4):66 (84.6) | 4 (14.3):24 (85.7) | 1.000 |

| Past-surgical history | |||

| Non-inflammatory/inflammatory diseases (%) | 52 (66.7):26 (33.3) | 24 (85.7):4 (14.3) | 0.085 |

| Malignant/benign diseases (%) | 38 (48.7):40 (51.3) | 15 (53.6):13 (46.4) | 0.083 |

| Open/laparoscopic (%) | 68 (87.2):10 (12.8) | 19 (67.9):9 (32.1) | 0.041 |

| Upper gastrointestinal (%) | 21 (26.9) | 4 (14.3) | 0.205 |

| Hepato-biliary-pancreatic | 10 (12.8) | 3 (10.7) | 1.000 |

| Lower gastrointestinal (%) | 35 (44.9) | 12 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| Gynaecological | 16 (20.5) | 7 (25.0) | 0.604 |

| Others (%) | 14 (17.9) | 8 (28.6) | 0.180 |

| Number of surgeriesa | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.3) | 0.787 |

| Number of past ASBO (admission)a | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 0.583 |

| Interval from past-surgery to ASBO (years)a | 8.5 (2.4-21.0) | 6.0 (0.9-22.0) | 0.472 |

| Blood test on admission | |||

| White blood cell counts (×103/dL)a | 9.3 (7.0-12.3) | 7.9 (7.0-10.6) | 0.422 |

| Creatine phosphokinase (IU/L)a | 81 (51-127) | 66 (38-124) | 0.194 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL)a | 0.5 (0.1-2.2) | 0.6 (0.2-2.1) | 0.982 |

| CT findings on admission | |||

| Ascites (yes:no) (%) | 31 (39.7):47 (60.3) | 16 (57.1):12 (42.9) | 0.126 |

| LT decompression-related | |||

| Bridge from NGT to LT intubation (%) | 13 (16.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | 1.000 |

| Interval from diagnosis to LT intubation (days)a | 0 (0-1) | 1 (1.0-2.3) | <0.001 |

| Drainage volume via LT (1st day) (ml)a | 537 (309-1237) | 1103 (835-2394) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal X-P findings | |||

| Passage of WSCA to colon within 48 h (yes:no) (%) | 52 (66.7):26 (33.3) | 9 (32.1):19 (67.9) | 0.020 |

| Small bowel dilatation at 48 h (yes:no) (%) | 30 (38.5):48 (61.5) | 26 (92.9):2 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Clinical course-related | |||

| Interval from LT intubation to surgerya | - | 7.0 (4.3-9.0) | - |

| Duration of hospital stay (days)a | 12.0 (9.5-16.5) | 24.0 (19.0-34.5) | <0.001 |

| Surgical procedures after NOM failure | |||

| Open small bowel resection | - | 13 (46.4) | |

| Laparoscopic adhesiolysis | - | 6 (21.4) | |

| Open adhesiolysis | - | 5 (17.9) | |

| Open intestinal bypass | - | 4 (14.3) |

Abbreviations: ASBO, adhesive small bowel obstruction; NGT, nasogastric decompression tube; LT, long transnasal intestinal tube; WSCA, water-soluble contrast agent; NOM, non-operative management

aMedian (interquartile range)

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis for transition to surgical intervention are shown in Table 2. Drainage volume via the LT ≥665 ml on day 1, interval between diagnosis of ASBO and LT intubation, and small bowel dilatation at 48 h were identified to be independent predictors of transition to surgical intervention (odds ratios 7.10, 1.42, and 19.81, respectively; 95% confidence intervals 1.63-30.94, 1.00-2.02, and 3.04-129.10; P-values 0.009, 0.047, and 0.002).

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Transition to Surgery.

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index | |||

| <20.9 kg/m2vs. ≥20.9 kg/m2 | 2.38 | 0.68 – 8.39 | 0.177 |

| Past-surgical approach | |||

| Laparoscopic vs. Open | 1.97 | 0.40 – 9.64 | 0.403 |

| Drainage volume via LT (1st day) | |||

| ≥665 ml vs. <665 ml | 7.10 | 1.63 - 30.94 | 0.009 |

| Passage of WSCA to colon within 48 h | |||

| No vs. Yes | 0.69 | 0.18 - 2.60 | 0.586 |

| Interval from diagnosis to LT intubation (per 1day) | 1.42 | 1.00 - 2.02 | 0.047 |

| Small bowel dilatation at 48 h | |||

| Yes vs. No | 19.81 | 3.04 - 129.10 | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: LT, long transnasal intestinal tube; WSCA, water-soluble contrast agent

Body mass index and drainage volume via LT (1st day) were divided using the cut-off of respective median values.

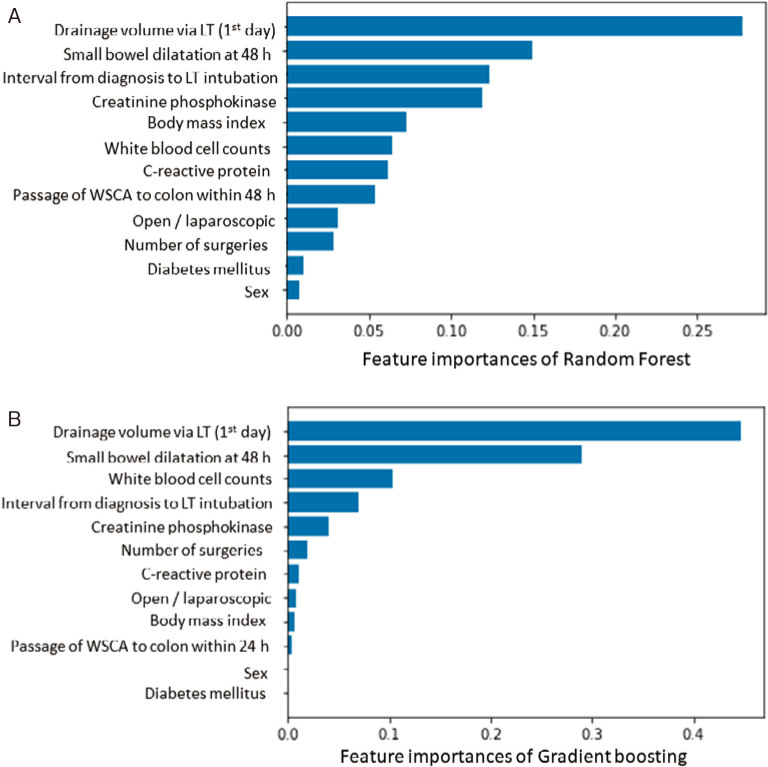

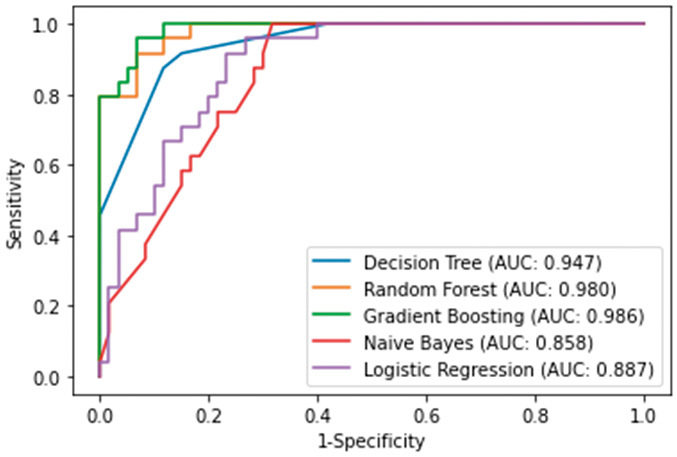

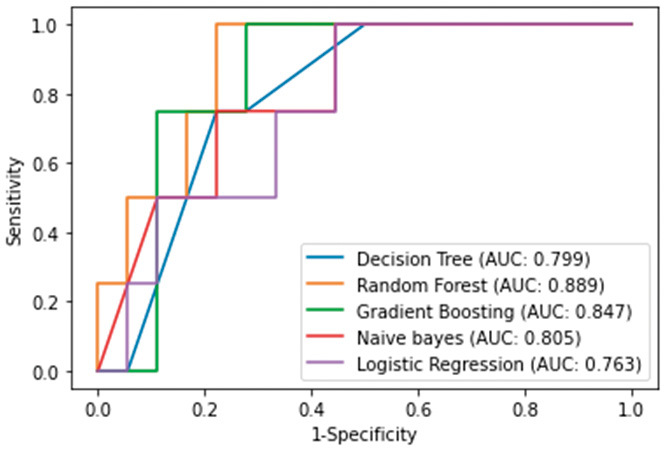

The relative importance of variables in the random forest and gradient boosting algorithms for prediction of transition to surgical intervention is shown in Figure 1A, 1B. The top three important variables were identified to be drainage volume via the LT on day 1, small bowel dilatation at 48 h, and interval between diagnosis of ASBO and LT intubation by the random forest algorithm and drainage volume via the LT on day 1, small bowel dilatation at 48 h, and white blood cell count by the gradient boosting algorithm. The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the five ML algorithms are shown for the training set in Figure 2 and for the test set in Figure 3. A summary of the performance of each algorithm in each set is shown in Table 3. In the training set, the gradient boosting algorithm had the highest AUC (0.986, with an accuracy of 0.917 and a precision of 0.905). In the test set, the random forest algorithm had the highest AUC (0.889, with an accuracy of 0.864 and a precision of 0.667).

Figure 1.

Feature importances of random forest algorithm (A) and gradient boosting (B) for prediction of surgical intervention in ASBO patients.

Abbreviations: ASBO, adhesive small bowel obstruction; LT, long transnasal intestinal tube; WSCA, water-soluble contrast agent

Figure 2.

ROC curves of ML algorithms predicting surgical intervention in ASBO patients in training set.

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristics; ML, machine-learning; ASBO, adhesive small bowel obstruction

Figure 3.

ROC curves of ML algorithms predicting surgical intervention in ASBO patients in test set.

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristics; ML, machine-learning; ASBO, adhesive small bowel obstruction

Table 3.

Forecast Results for Training and Test Sets.

| Training set | ||||

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | AUC | |

| Decision Tree | 0.881 | 0.750 | 0.875 | 0.947 |

| Random Forest | 0.905 | 0.864 | 0.792 | 0.980 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.917 | 0.905 | 0.792 | 0.986 |

| Naïve bayes | 0.774 | 0.600 | 0.625 | 0.858 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.786 | 0.714 | 0.416 | 0.887 |

| Test set | ||||

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | AUC | |

| Decision Tree | 0.773 | 0.429 | 0.750 | 0.799 |

| Random Forest | 0.864 | 0.667 | 0.500 | 0.889 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.864 | 0.600 | 0.750 | 0.847 |

| Naïve bayes | 0.773 | 0.400 | 0.500 | 0.805 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.773 | 0.333 | 0.250 | 0.763 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve

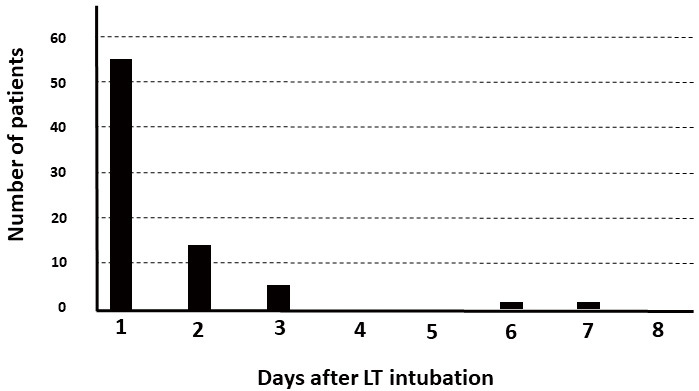

The interval between LT intubation and first passage of flatus in the non-surgery group is shown in Figure 4. Although each one patient had passes of first flatus on six and seven days after LT intubation, 97.4% (n=76) of patients had passes of first flatus until three days.

Figure 4.

Interval from LT intubation to pass first flatus among patients in the non-operative group.

Abbreviations: LT, long transnasal intestinal tube

Discussion

This retrospective study of 106 patients with ASBO who underwent NOM with LT intubation as their initial treatment had two important findings. First, traditional logistic regression analysis identified a drainage volume of ≥665 ml via the LT on day 1, interval between diagnosis of ASBO and LT intubation, and small bowel dilatation at 48 h after LT intubation to be independent predictors of the need for transition to surgical intervention. ML predicted transition to surgical intervention with high AUCs in both the training and test sets. Second, the guideline[10] recommended period for initial NOM of 72 h seems to be reasonable, because 97.4% of patients had passes of first flatus until three days among patients in the non-operative group. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to establish an ML model that can predict the likelihood of transition from NOM to surgical intervention in patients with ASBO.

Intestinal decompression using an NGT or LT is a major cornerstone of NOM for ASBO[10]. There has long been debate about which type of tube is superior, but no definitive conclusions can be drawn because of the paucity of data[12,24,25]. A recent randomized trial that included 186 patients with ASBO in China found that the failure rate was lower in the LT group than in the NGT group (10.4% vs 53.3%)[26]. The reasons for this apparent superiority of LT may include the following: removal of kinks in the obstructed small-bowel loops, suction of retained gastric and intestinal fluid close to the obstruction point, thereby reducing the intraluminal pressure between the tube and the obstructed small intestine, and reduction of ischemic necrosis in the bowel[11,27]. Gowen et al.[13,28] found that the LT had significant clinical and economic advantages over the NGT and recommended LT intubation for patients in whom NGT decompression was unsuccessful, regardless of the increased invasiveness of the LT, placement of which requires endoscopic guidance, and the potential complications, including intestinal perforation and knotting[29]. Therefore, the NOM strategy used in our department, which is similar to that described by Gowen et al.[13,28], seems reasonable in terms of the balance between advantages and disadvantages. Another consideration is that a considerable proportion of cases of ASBO are mild and do not necessarily warrant intestinal decompression. For example, in a retrospective study by Shinohara et al.[30], 51.3% of patients with ASBO could be managed without an NGT and there was no significant difference in the surgical intervention rate between NOM with an NGT and NOM without an NGT (7.4% vs. 12.9%, P=0.126). Another study found that 57.7% of 155 patients with ASBO recovered after 2 days of NOM[31]. On balance, the evidence to date suggests that almost all patients with mild ASBO recover relatively soon after symptom onset and are unlikely to be candidates for surgical intervention. Therefore, our inclusion criteria of patients who required for LT intubation seems to be clinically significant, because the results would be useful in patients who are really concerned for surgical intervention.

Interestingly, LT intubation-required ASBO after laparoscopic surgery required more surgical intervention than that of open surgery. The detailed mechanism is unknown, but we think that laparoscopic surgery-induced very localized intestinal adhesion with freedom of the surrounding intestinal tract may cause strong intestinal flexion and kink that, once developed, may not improve conservatively.

Identification of a greater drainage volume via the LT and failure of WSCA to pass through the colon as predictors of the need for transition from NOM to surgical intervention seems reasonable. However, the predictive ability of the interval between diagnosis of ASBO and LT intubation is interesting. Although there are several factors that could have introduced a degree of selection bias in this study, the most important one is likely to be earlier consideration of LT intubation in more severe cases. However, the difference in this interval between the surgical group and the non-surgical group was small (mean, 1.3 days). Nevertheless, as the findings of our multivariate analysis showed, this difference could be clinically significant. Delayed suction of retained intestinal fluid by the LT close to the obstruction point might cause intractable intestinal ischemia followed by edema and further obstruction. Of note, it has been demonstrated in animal models that intestinal ischemia followed by reperfusion (i.e., ischemia-reperfusion injury) results in irreversible cellular dysfunction and vascular and intestinal tissue damage[32,33]. Nevertheless, it is quite possible that the results were influenced by case-to-case variability in the indications and timing of LT insertion due to the retrospective nature of the study. Future prospective studies that strictly define this point are expected.

Deep learning models are complicated and were not used in this study because of the small number of samples and to avoid overfitting. Among the algorithms tested, the random forest achieved the best balance in AUCs between the training and test sets. The random forest algorithm consists of an ensemble of decision trees and is based on the bagging method. This algorithm has the advantages of considerable stability and the ability to reduce the risk of overfitting. Therefore, it was best suited to our small dataset. In contrast, gradient boosting trains weak decision trees sequentially, with each subsequent model correcting the errors of its predecessors. Tuning hyperparameters for gradient boosting is more delicate compared to random forest, and overfitting should be carefully managed, but it often yields higher predictive performance. Our ML algorithms were designed retrospectively after obtaining measurements for a certain period of time. Therefore, these algorithms require adaptation to some degree for application in real time or could show reduced performance.

In conclusion, this study had several important findings. NOM was unsuccessful in 26% of our patients with ASBO who underwent LT intubation. Traditional logistic regression analysis identified drainage volume via the LT on day 1, interval between diagnosis of ASBO and LT intubation, and small bowel dilatation at 48 h after LT intubation to be independent predictive factors for transition from NOM to surgical intervention. ML algorithms, especially the random forest, could predict transition to surgical intervention with high AUCs. The guideline recommended period for initial NOM of 72 h seems to be reasonable. These findings can be used to develop a framework for earlier clinical decision-making in these patients.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors are in agreement with the content of the manuscript. Authors' contributions are study concept and design; AM and FA, acquisition of data; FA, SM, NS, YK, and KS, analysis and interpretation of data; AM, and SK, drafting of the manuscript; AM, statistical analysis: AM and SK, revising of the manuscript; TY, and HS, study supervision; HY. Akihisa Matsuda and Sho Kuriyama contributed equally to this work.

Approval by Institutional Review Board (IRB)

No. 522 at Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital

Disclaimer

Takeshi Yamada is one of the Associate Editors of Journal of the Anus, Rectum and Colon and on the journal's Editorial Board. He was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to accept this article for publication at all.

Acknowledgements

We thank Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Aquina CT, Becerra AZ, Probst CP, et al. Patients With Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction Should Be Primarily Managed by a Surgical Team. Ann Surg. 2016 Sep; 264(3): 437-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuda A, Yamada T, Ohta R, et al. Surgical Site Infections in Gastroenterological Surgery. J Nippon Med Sch. 2023 Mar; 90(1): 2-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kossi JA, Salminen PT, Laato MK. Surgical workload and cost of postoperative adhesion-related intestinal obstruction: importance of previous surgery. World J Surg. 2004 Jul; 28(7): 666-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh JA, Ko CY, Maggard MA, et al. What is the rate of small bowel obstruction after colectomy? Am Surg. 2008 Oct; 74(10): 1001-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih SC, Jeng KS, Lin SC, et al. Adhesive small bowel obstruction: how long can patients tolerate conservative treatment? World J Gastroenterol. 2003 Mar; 9(3): 603-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornblade LW, Verdial FC, Bartek MA, et al. The Safety of Expectant Management for Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction: A Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 Apr; 23(4): 846-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson AT, Sr. Early operation in the treatment of small bowel obstruction. J Natl Med Assoc. 1981 Mar; 73(3): 245-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabri PJ, Rosemurgy A. Reoperation for small intestinal obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 1991 Feb; 71(1): 131-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schraufnagel D, Rajaee S, Millham FH. How many sunsets? Timing of surgery in adhesive small bowel obstruction: a study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Jan; 74(1): 181-7;discussion 7-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ten Broek RPG, Krielen P, Di Saverio S, et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2017 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J Emerg Surg. 2018; 13(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong XW, Huang SL, Jiang ZH, et al. Nasointestinal tubes versus nasogastric tubes in the management of small-bowel obstruction: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Sep; 97(36): e12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleshner PR, Siegman MG, Slater GI, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of short versus long tubes in adhesive small-bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 1995 Oct; 1670(4): 366-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowen GF. Long tube decompression is successful in 90% of patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 2003 Jun; 185(6): 512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender JS, Busuito MJ, Graham C, et al. Small bowel obstruction in the elderly. Am Surg. 1989 Jun; 55(6): 385-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fevang BT, Fevang JM, Soreide O, et al. Delay in operative treatment among patients with small bowel obstruction. Scand J Surg. 2003; 92(2): 131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fevang BT, Jensen D, Svanes K, et al. Early operation or conservative management of patients with small bowel obstruction? Eur J Surg. 2002; 168(8-9): 475-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keenan JE, Turley RS, McCoy CC, et al. Trials of nonoperative management exceeding 3 days are associated with increased morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for uncomplicated adhesive small bowel obstruction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014 Jun; 76(6): 1367-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igarashi Y, Nishimura K, Ogawa K, et al. Machine Learning Prediction for Supplemental Oxygen Requirement in Patients with COVID-19. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022 May; 89(2): 161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kourou K, Exarchos TP, Exarchos KP, et al. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2015; 13(8-17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakhani P, Gray DL, Pett CR, et al. Hello World Deep Learning in Medical Imaging. J Digit Imaging. 2018 Jun; 31(3): 283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng PM, Tran KN, Whang G, et al. Refining Convolutional Neural Network Detection of Small-Bowel Obstruction in Conventional Radiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019 Feb; 212(2): 342-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanderbecq Q, Ardon R, De Reviers A, et al. Adhesion-related small bowel obstruction: deep learning for automatic transition-zone detection by CT. Insights Imaging. 2022 Jan; 13(1): 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herlinger HB, B.A. Anatomy of the Small Intestine. Clinical Imaging of the Small Intestine: Springer; 1999. 3-12 p. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bizer LS, Liebling RW, Delany HM, et al. Small bowel obstruction: the role of nonoperative treatment in simple intestinal obstruction and predictive criteria for strangulation obstruction. Surgery. 1981 Apr; 89(4): 407-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brolin RE, Krasna MJ, Mast BA. Use of tubes and radiographs in the management of small bowel obstruction. Ann Surg. 1987 Aug; 206(2): 126-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen XL, Ji F, Lin Q, et al. A prospective randomized trial of transnasal ileus tube vs nasogastric tube for adhesive small bowel obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr; 18(16): 1968-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, Micon LT, et al. Nasointestinal tube for decompression or enteroclysis: experience with 150 patients. Abdom Imaging. 1994 Mar-Apr; 19(2): 108-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gowen GF. Rapid resolution of small-bowel obstruction with the long tube, endoscopically advanced into the jejunum. Am J Surg. 2007 Feb; 193(2): 184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter TB, Fon GT, Silverstein ME. Complications of intestinal tubes. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981 Sep; 76(3): 256-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shinohara K, Asaba Y, Ishida T, et al. Nonoperative management without nasogastric tube decompression for adhesive small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 2022 Jun; 223(6): 1179-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakakibara T, Harada A, Yaguchi T, et al. The indicator for surgery in adhesive small bowel obstruction patient managed with long tube. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007 Apr-May; 54(75): 787-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda A, Yang WL, Jacob A, et al. FK866, a visfatin inhibitor, protects against acute lung injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion in mice via NF-kappaB pathway. Ann Surg. 2014 May; 259(5): 1007-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vollmar B, Menger MD. Intestinal ischemia/reperfusion: microcirculatory pathology and functional consequences. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011 Jan; 396(1): 13-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]