Abstract

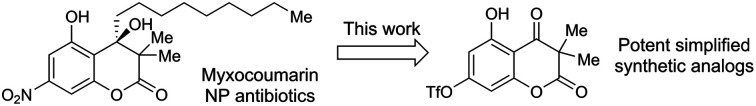

The rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance in recent years poses a substantial global health threat. Thus, the discovery of potent novel antibiotics is of utmost importance. One such compound class with promising antibiotic potential are the myxocoumarins from Stigmatella aurantiaca MYX-030, which exhibit exceptional antibiotic activities against several Gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA. Interestingly, the synthetic chromene dione precursors lacking the alkyl side chain also display promising antibiotic potential. Within this work, a focused library of chromene diones resembling the myxocoumarin A core structure was synthesized to explore structure–activity relationships. We were able to identify derivatives equipotent to the natural product but devoid of the alkyl chain and the nitro substituent to significantly facilitate synthetic access.

The myxocoumarins are natural products with strong antibiotic activity. We herein explored structural simplification of the myxocoumarins while aiming to retain their antibacterial properties. This led to the discovery of potent myxochromene diones.

Introduction

Myxobacteria, Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the class of δ-proteobacteria, are valuable producers of biologically active secondary metabolites.1 Myxobacterial natural products display a wide structural diversity and novel modes of action.1–4 Besides antineoplastic,1–4 antiparasitic,2 antiviral,2–5 and antimalarial2–4 properties, many myxobacterial natural products exhibit antibacterial and antifungal activities.2–4,6 One clinically relevant example is ixabepilone (1; Fig. 1), an epothilone analog that is an FDA-approved anti-cancer chemotherapeutic for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.7–9 Another prominent example is the polyketide soraphen A1α (2). This broad-spectrum fungicide inhibits fungal acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) in the biosynthesis of fatty acids.10–12 A myxobacterial metabolite with antibacterial potential is the macrolactone sorangicin (3), which inhibits the eubacterial RNA polymerase affecting RNA synthesis.13,14

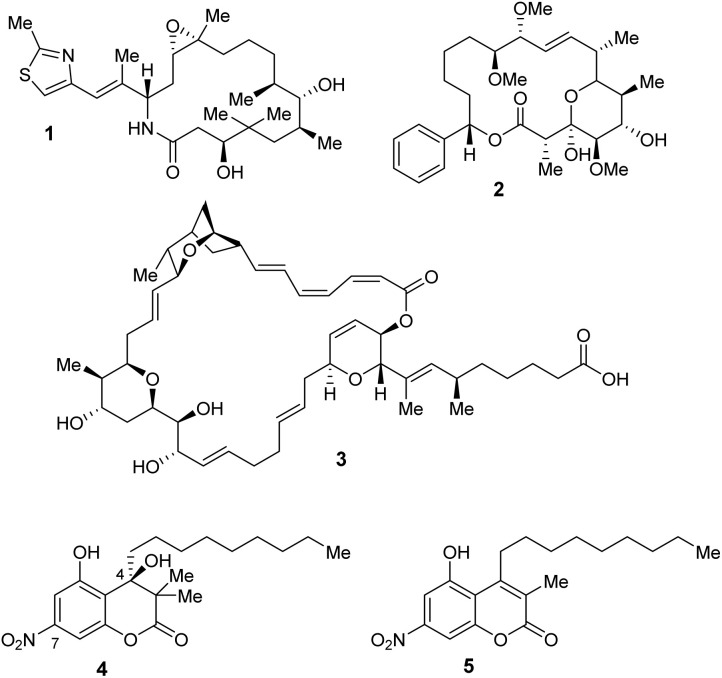

Fig. 1. Structures of the myxobacterial natural products ixabepilone (1), soraphen A1α (2), sorangicin (3), and the myxocoumarins A (4) and B (5).

Myxocoumarins A (4) and B (5) were first isolated in 2013 from the strain Stigmatella aurantiaca MYX-030.15 Both natural products contain a coumarin core structure, a nitro substitution at the aromatic system as well as an unusual, long alkyl side chain. The biological evaluation of myxocoumarin B (5) was enabled by the development of the first total synthesis in 2019.16 Comprehensive structure activity relationship studies revealed a high antibacterial potential as well as a lack of antifungal properties for 5.17 In the initial biological evaluation of myxocoumarin A (4), a strong broad range antifungal activity against agriculturally relevant pathogens, including Blumeria graminis, Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium culmorum, Magnaprthe grisea and Phaeospaeria nodrum, was found.15,18 However, a lack of activity against the human fungal pathogens Candida auris and C. albicans was observed during the biological investigation of synthetic 4. Interestingly, 4 was found to exhibit excellent activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus and Bacillus subtilis.18

Besides 4 and first derivatives thereof, its direct synthetic chromene dione precursor, with the myxocoumarin substitution pattern in place only lacking the long alkyl side chain, was biologically evaluated as well and found to also have promising activity against Gram-positive bacteria. Thus, we aimed to explore the antibacterial potential of these chromene dione scaffolds more broadly within this work.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of myxocoumarin-based chromene diones

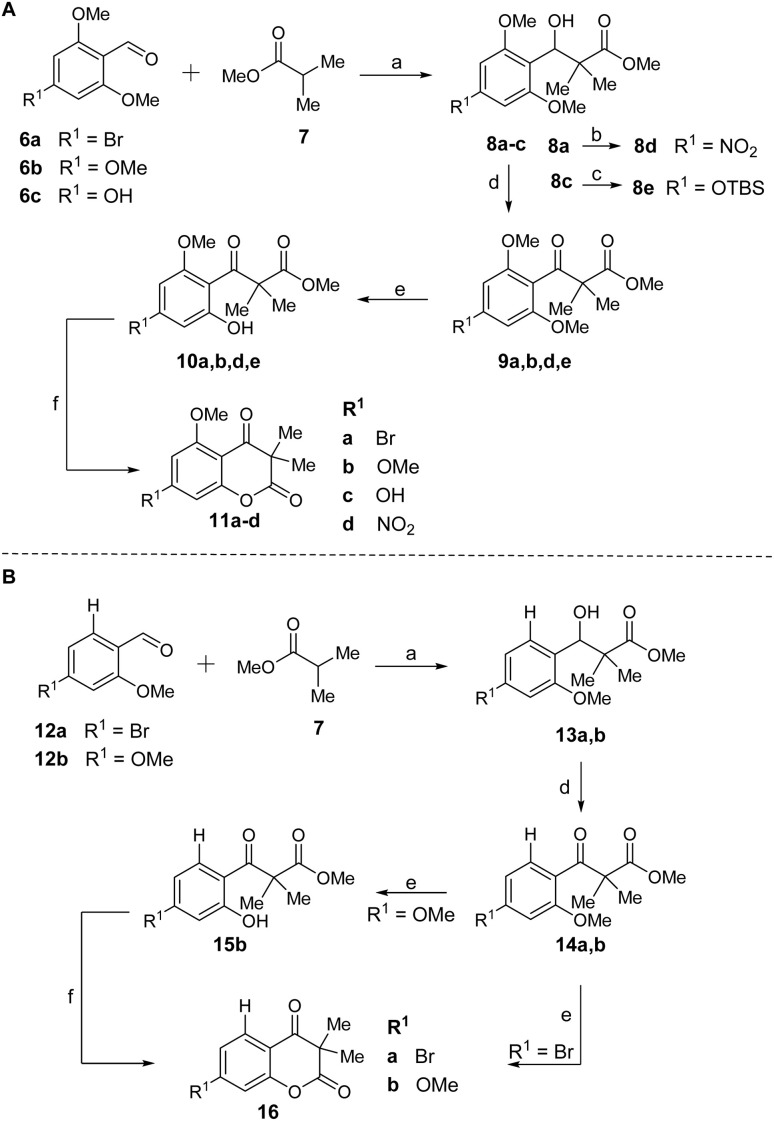

The first step of the total synthesis of 4, as developed by our group in 2023,18 employs an aldol addition using methyl isobutyrate (7) and 4-bromo-2,6-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (6a) to synthesize β-hydroxy ester 8a (Scheme 1). The substitution pattern at the aromatic portion can readily be altered by simple exchange of the aldehyde building blocks. Besides 6a, we thus employed 2,4,6-trimethoxybenzaldehyde (6b), 4-hydroxy-2,6-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (6c), 4-bromo-2-methoxybenzaldehyde (12a) and 2,4-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (12b) within the current work to deliver benzylic alcohol 8a–c and 13a,b. Compound 8a was then used to convert into the nitro-bearing derivative 8d by Pd-catalyzed nitration reaction. The aldol addition was followed by an oxidation with DMP, resulting in the respective β-keto esters 9a,b,d,e and 14a,b. Phenolic precursor 8c had to be TBS-protected for this oxidation step to generate intermediate β-hydroxy ester 8e. The β-keto esters were converted into 10a,b,d,e and 15b by selective O-demethylation with BBr3. Lastly, a FeCl3-catalyzed trans-esterification of 10 and 15b afforded the cyclized chromene diones 11a–d and 16b. For compound 14a, a direct cyclization was observed in the O-demethylation step, resulting in 16a. To test the influence of the C5 and C7 substituents of the chromene diones on their biological properties, chromene diones 11a–d were further derivatized (Fig. 2 and Scheme 2).

Scheme 1. Synthetic route to chromene dione derivatives. (A) Synthetic pathway to access derivatives 11a–d. (B) Synthesis towards chromene diones 16a,b. Reagents and conditions: (a) 1. n-BuLi (1.5 eq.), DIPA (1.5 eq.), THF, −78 °C, 1 h; 2. 7 (1.0 eq.), −78 °C, 1 h; 3. 6a–c/12a,b (1.1 eq.), −78 °C, 3.5 h. (b) Pd2(dba)3 (2.5 mol%), t-BuBrettPhos (6.0 mol%), TDA (5.0 mol%), NaNO2 (2.0 eq.), t-BuOH, 100 °C, 22 h. (c) Imidazole (1.05 eq.), TBSCl (1.05 eq.), DMF, 0 °C to rt, 16 h. (d) DMP (1.1 eq), DCM, rt, 3–5 h. (e) BBr3 (1.1 eq.), DCM, −78 °C to rt, 13–20 h. (f) FeCl3·6H2O (0.5 eq.), DCM, 40 °C, 24–72 h.

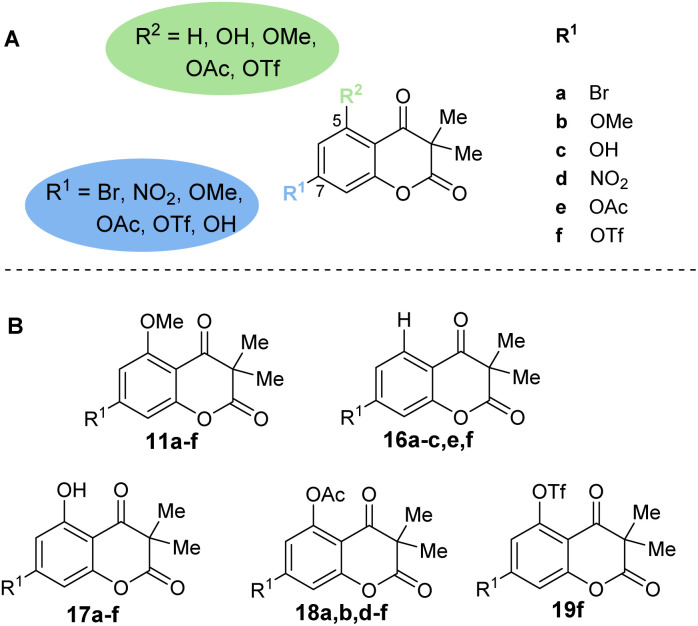

Fig. 2. (A) Structural changes introduced into the chromene dione scaffold. (B) Chemical structures of O-methylated (11), not substituted (16), phenolic (17), O-acetylated (18) and O-triflated (19) chromene dione analogs.

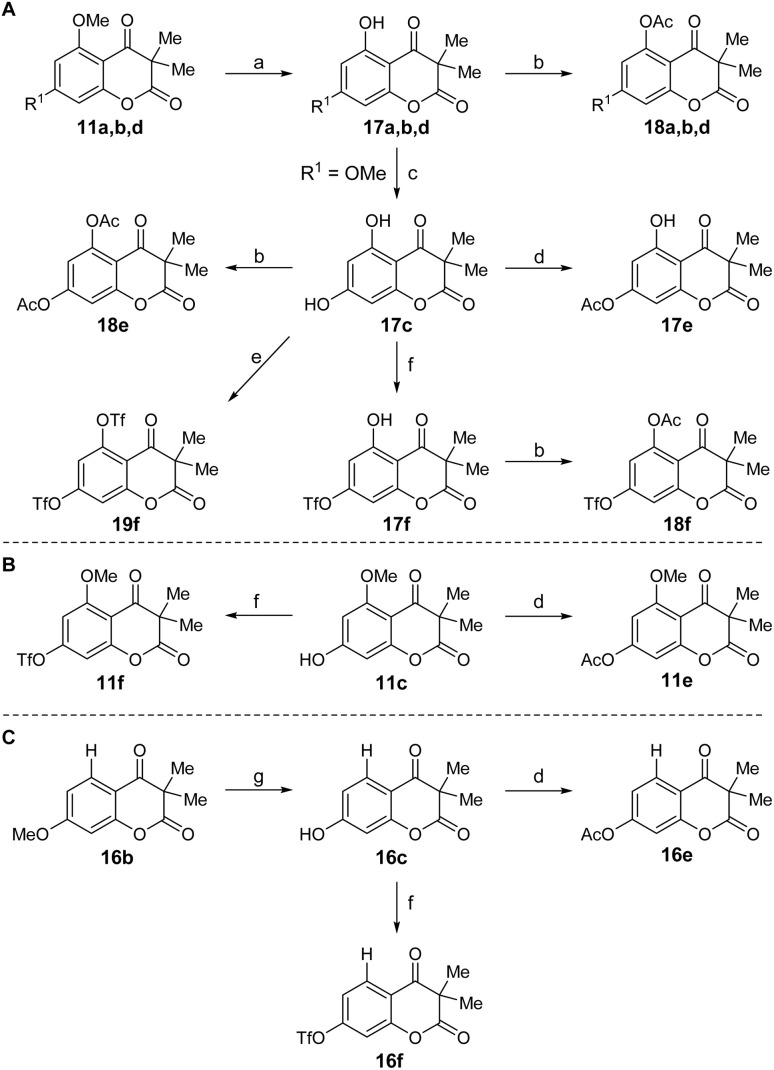

Scheme 2. Derivatization of chromene diones by selective O-demethylation, O-acetylation and O-triflation starting from 11a,b,d (A), 11c (B), 16b (C), respectively. Reagents and conditions: (a) BBr3 (1.1–2.5 eq.), DCM, −78 °C (11d) or 0 °C (11a,b) to rt, 20 h. (b) Ac2O (135–200 eq.), pyridine (160–235 eq.), DCM, rt, 21 h. (c) BBr3 (5.0 eq.), DCM, 0 to 40 °C, 3 d. (d) Ac2O (1.05–1.1 eq.), pyridine (1.05–1.5 eq.), DCM, rt, 17–20 h. (e) Tf2O (2.2 eq.), pyridine (2.2 eq.), DCM, 0 °C to rt, 4.5 h. (f) Tf2O (1.05–1.1 eq.), pyridine (1.05–1.5 eq.), DCM, 0 °C to rt, 4.5 h. (g) BBr3 (3.5 eq.), DCM, −78 °C to rt, 7 d.

Compounds 17a,b,d were obtained through selective O-demethylation of 11a,b,d using BBr3. To furnish compound 17c, another O-demethylation had to be carried out from derivative 17b. Additionally, compound 16c was afforded by selective O-demethylation of 16b. Using hydroxy derivatives 11c, 16c and 17a–d, a selection of O-acetylated and O-triflated chromene diones was prepared. While compounds 11e,f, 16e,f and 17e,f were obtained by either selective O-acetylation or O-triflation of the C7 hydroxy group of 11c, 16c and 17c, respectively, 18a,b,d and 18f were generated by selective O-acetylation of the C5 hydroxy group of 17a–d. Compounds 18e and 19f were made available using 17c and an excess amount of Ac2O and Tf2O, respectively (Scheme 2).

Biological activities

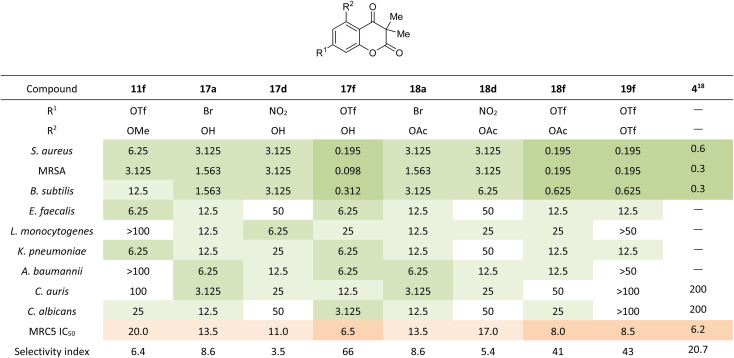

With 23 chromene dione derivatives in hand (Fig. 2), we next investigated their biological profile, particularly focusing on antibacterial activities. All derivatives were initially assessed against the Gram-positive bacterial strain S. aureus and the human fungal pathogen C. auris which was of interest due to its multidrug resistance to all established antifungal classes. Most derivatives were inactive against both the bacterial and the fungal pathogen at the maximum tested concentrations (100 μg mL−1). Derivatives 17b and 18b showed weak MIC values of 50 μg mL−1 against S. aureus. However, a total of eight chromene diones showed interesting antibacterial activity against S. aureus and were thus evaluated against a broader range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Table 1), including MRSA, B. subtilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Listeria monocytogenes and Actinerobacter baumannii. Further, the most common opportunistic human fungal pathogen C. albicans was also included in the screening.

Heat map of the antibacterial and antifungal activity profile (in μg mL−1) of chromene diones 11f, 17a,d,f, 18a,d,f and 19f against S. aureus NCTC 6571, S. aureus MRSA ATCC 43300, B. subtilis NCTC 5398, E. faecalis ATCC 29212, L. monocytogenes NCTC 1194, K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA 2146, A. baumannii ATCC 19606, C. auris ATCC 21092 and C. albicans ATCC 10231 compared to toxicity against MRC5 human fibroblast cells. The activity profile of myxocoumarin A (4) is given for comparisona.

|

NCTC = National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC, Culture Collection of Public Health, Salisbury, UK). ATCC = American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia, USA). Green color indicates biological activity (darker green equals higher activity), orange color toxicity (darker orange equals higher toxicity).

The triflate chromene dione 17f exhibited very strong antibacterial potential with MIC values as low as 0.195 μg mL−1 against S. aureus and 0.098 μg mL−1 against MRSA combined with a 33 to 66-fold higher IC50 value in MRC5 human fibroblast cells. The triflate derivatives 18f and 19f displayed equally strong antibacterial activities with MIC values of 0.195 μg mL−1 against S. aureus and MRSA combined with an up to 43-fold higher IC50 value against MRC5. Bromide derivatives 17a and 18a as well as nitro-substituted analogs 17d and 18d also exhibited strong activities against the Gram-positive strains S. aureus and MRSA with MIC values between 1.563 μg mL−1 and 3.125 μg mL−1. However, the MRC5 IC50 values only were between 3.5 and 8.6-fold higher than the respective MIC values. In relation to their MRC5 IC50 values, none of the eight compounds showed promising activities against the Gram-negative strains K. pneumoniae and E. faecalis nor against the Gram-positive bacterial strain A. baumannii.

The observed antibacterial activities make a clear structure activity relationship obvious, with bioactivities only being observed for chromene diones with R1 = Br, NO2 or OTf at C7. The introduction of other functional groups at this position, such as hydroxy, methoxy or acetyl, leads to the loss of antibacterial activity. Similarly, most compounds with antibacterial potential only tolerate hydroxy and acetyl groups at C5 (R2 = OH, OAc). The only exception is the C7 triflate derivative, which also possess antibiotic potential with R2 = OTf. Surprisingly, the triflate chromene diones tolerate a methoxy group at C5 (11f), whilst still displaying good biological activity. Overall, the triflate analogs 17f, 18f and 19f display the strongest antibiotic potential against S. aureus and MRSA. In addition, these three chromene diones show stronger antibacterial potential and similar in vitro toxicity compared to the natural product myxocoumarin A (4) and known derivatives.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our work provides first structure activity data on a novel class of chromene dione antibiotics inspired by the myxocoumarin scaffold. The most potent derivatives possess remarkable sub-nanomolar antibacterial potential, even against MRSA, comparable to the structurally more complex parent natural product myxocoumarin A (4). The synthesis of many of the most active analogs is significantly more efficient, with overall reduced step-count and the omission of the relatively low-yielding Pd-catalyzed nitration step required for the synthesis of the natural product. Therefore, these potent chromene dione analogs pose a valuable alternative to the myxo-coumarins, not only as they are more readily accessible by synthesis, but also due to their antifungal activity against Candida species, which is not found in the natural product.

Data availability

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the ESI.†

Author contributions

A. B. and G. H. performed all synthetic and analytic work. A. B., S. V., and J. N. R. evaluated the biological activity of the compounds. J. N. R., S. V., and T. A. M. G. conceptualized and supervised the project. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was generously funded by the German Research Foundation (TAMG DFG GU 1233/1-1 and INST 269/971-1), the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (JNR; agreement no. 451-03-47/2023-01/ 200042) and the DAAD (TAMG, NJR; Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, Bilateral Project of Germany with the Republic of Serbia to SV and TAMG – 2020/2021). We thank Dr T. Lübken and his team (TU Dresden, Organic Chemistry I) for recording NMR spectra.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Biological Data, experimental procedures, analytical data and spectra. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra05941g

References

- Wenzel S. C., and Müller R., Myxobacteria - unique microbial secondary metabolite factories, Comprehensive Natural Products II: Chemistry and Biology, ed. L. Mander, and H.-W. Liu, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2010, pp. 189–222 [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J. Abou Fayad A. Müller R. Natural products from myxobacteria: novel metabolites and bioactivities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017;34:135. doi: 10.1039/c6np00106h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman K. J. Müller R. Myxobacterial secondary metabolites: bioactivities and modes-of-action. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:1276. doi: 10.1039/c001260m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat M. A. Mishra A. K. Bhat M. A. Banday M. I. Bashir O. Rather I. A. Rahman S. Shah A. A. Jan A. T. Myxobacteria as a Source of New Bioactive Compounds: A Perspective Study. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1265. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13081265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. P. Hinkelmann B. Fleta-Soriano E. Steinmetz H. Jansen R. Diez J. Frank R. Sasse F. Meyerhans A. Identification of myxobacteria-derived HIV inhibitors by a high-throughput two-step infectivity assay. Microb. Cell Factories. 2013;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäberle T. F. Lohr F. Schmitz A. König G. M. Antibiotics from myxobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31:953. doi: 10.1039/c4np00011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K. L. Bradley T. Budman D. R. Novel microtubule-targeting agents—the epothilones. Biol.: Targets Ther. 2008;2:789. doi: 10.2147/btt.s3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerton N. Ixabepilone (Ixempra), a Therapeutic Option for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Breast Cancer. P&T. 2008;33:523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez R. H. Valero V. Hortobagyi G. N. Ixabepilone for the treatment of breast cancer. Ann. Med. 2011;43:477. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.579151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerth K. Bedorf N. Irschik H. Höfle G. Reichenbach H. The soraphens: A family of novel antifungal compounds from Sorangium cellulosum (Myxobacteria) J. Antibiot. 1994;47:23. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. Volrath S. L. Weatherly S. C. Elich T. D. Tong L. A Mechanism for the Potent Inhibition of Eukaryotic Acetyl-Coenzyme A Carboxylase by Soraphen A, a Macrocyclic Polyketide Natural Product. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:881. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naini A. Sasse F. Brönstrup M. The intriguing chemistry and biology of soraphens. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019;36:1394. doi: 10.1039/c9np00008a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irschik H. Jansen R. Gerth K. Höfle G. Reichenbach H. The mechanism of action of myxovalargin A, a peptide antibiotic from Myxococcus fulvus. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1237. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E. A. Pavlova O. Zenkin N. Leon F. Irschik H. Jansen R. Severinov K. Darst S. A. Structural, Functional, and Genetic Analysis of Sorangicin Inhibition of Bacterial RNA Polymerase. EMBO J. 2005;24:674. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulder T. A. M. Neff S. Schüz T. Winkler T. Gees R. Böhlendorf B. The Myxocoumarins A and B from Stigmatella aurantiaca strain MYX-030. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013;9:2579. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J. I. Kusserow K. Hertrampf G. Pavic A. Nikodinovic-Runic J. Gulder T. A. M. Synthesis and initial biological evaluation of myxocoumarin B. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019;17:1966. doi: 10.1039/c8ob02273a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertrampf G. Kusserow K. Vojnovic S. Pavic A. Müller J. I. Nikodinovic-Runic J. Gulder T. A. M. Strong Antibiotic Activity of the Myxocoumarin Scaffold in vitro and in vivo. Chem.–Eur. J. 2022;28:14184. doi: 10.1002/chem.202200394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertrampf G. Vojnovic S. Müller J. I. Merten C. Nikodinovic-Runic J. Gulder T. A. M. Synthesis, Stereochemical Determination, and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Myxocoumarin A. J. Org. Chem. 2023;88:14184. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.3c01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the ESI.†