Abstract

Malonyl‐coenzyme A (CoA) is a key precursor for the biosynthesis of multiple value‐added compounds by microbial cell factories, including polyketides, carboxylic acids, biofuels, and polyhydroxyalkanoates. Owing to its role as a metabolic hub, malonyl‐CoA availability is limited by competition in several essential metabolic pathways. To address this limitation, we modified a genome‐reduced Pseudomonas putida strain to increase acetyl‐CoA carboxylation while limiting malonyl‐CoA utilization. Genes involved in sugar catabolism and its regulation, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and fatty acid biosynthesis were knocked‐out in specific combinations towards increasing the malonyl‐CoA pool. An enzyme‐coupled biosensor, based on the rppA gene, was employed to monitor malonyl‐CoA levels in vivo. RppA is a type III polyketide synthase that converts malonyl‐CoA into flaviolin, a red‐colored polyketide. We isolated strains displaying enhanced malonyl‐CoA availability via a colorimetric screening method based on the RppA‐dependent red pigmentation; direct flaviolin quantification identified four engineered strains had a significant increase in malonyl‐CoA levels. We further modified these strains by adding a non‐canonical pathway that uses malonyl‐CoA as precursor for poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) biosynthesis. These manipulations led to increased polymer accumulation in the fully engineered strains, validating our general strategy to boost the output of malonyl‐CoA–dependent pathways in P. putida.

Malonyl‐coenzyme A (CoA) is a key precursor for the biosynthesis of high‐value compounds by microbial cell factories, including polyketides, carboxylic acids, biofuels, and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). Here, we engineered Pseudomonas putida, a versatile bacterial platform, for enhanced malonyl‐CoA availability, validating the engineered strains for enhanced PHA accumulation from sugars.

INTRODUCTION

Malonyl‐coenzyme A (CoA) serves as a hub metabolite for the biosynthesis of lipids and acts as an attractive building block for the microbial production of biologically active polyketides and fatty acid‐derived compounds, including biofuels (Li et al., 2024). In most organisms, malonyl‐CoA is produced through acetyl‐CoA carboxylation by acetyl‐CoA carboxylase (ACC). Bacteria and plant chloroplasts possess a multi‐subunit ACC enzyme, which consists of three distinct domains responsible for catalyzing two separate reaction steps (Cronan, 2021a, 2021b; Cronan & Waldrop, 2002). The primary function of malonyl‐CoA in bacterial metabolism is serving as an extender unit for fatty acids synthesis (Polyak et al., 2012), while its role in the production of native secondary metabolites appears to be relatively minor (Cronan & Thomas, 2009; McNaught et al., 2023).

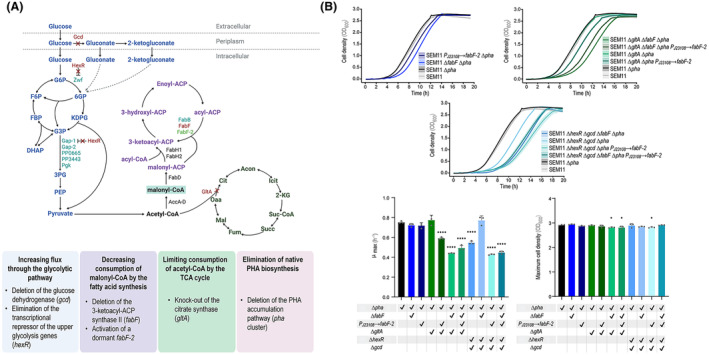

Several studies have focused on engineering model microorganisms to enhance the biosynthesis of malonyl‐CoA–derived compounds (Fowler et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2023; Milke et al., 2019; Milke & Marienhagen, 2020; Valdehuesa et al., 2013). In most cases, however, metabolic and regulatory bottlenecks have been encountered in the engineered strains, and productivity limitations have been identified in the associated bioprocesses. Typically, the relatively low availability of intracellular malonyl‐CoA is a primary constraint limiting product yield (Milke & Marienhagen, 2020), exposing the need for emerging metabolic engineering approaches to boost malonyl‐CoA levels. Redirecting fluxes through central carbon metabolism to enhance the availability of acetyl‐CoA, the immediate precursor of malonyl‐CoA, has been shown to promote the synthesis of malonyl‐CoA–derived products (Milke et al., 2018). Consequently, various metabolic engineering approaches have been implemented to enhance the synthesis of malonyl‐CoA while reducing the consumption of acetyl‐CoA. Some of the key metabolic and regulatory targets for manipulation are indicated in Figure 1A.

FIGURE 1.

Genetic modifications to boost malonyl‐CoA availability in Pseudomonas putida. (A) P. putida SEM11 was modified by knocking‐out various combinations of the four genes shown in red and reactivating a dormant FabF‐2 via promoter insertion in order to increase the malonyl‐CoA pool. In addition, the native gene cluster encoding the enzymes for PHA production and degradation was deleted to eliminate endogenous biopolymer production. Abbreviations: G6P, glucose‐6‐phosphate; 6PG, 6‐phosphogluconate; KDPG, 2‐keto‐3‐deoxy‐6‐phosphogluconate; F6P, fructose‐6‐phosphate; FBP, fructose‐1,6‐bisphosphate; G3P, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate; 3PG, 3‐phosphoglycerate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Cit, citrate; Acon, aconitate; Icit, isocitrate; 2‐KG, 2‐ketoglutarate; Suc‐CoA, succinyl‐CoA; Succ, succinate; Fum, fumarate; Mal, malate; and Oaa, oxaloacetate. (B) Growth curves of the resulting engineered strains. Cell density was estimated as the optical density measured at 600 nm (OD600). QurvE software was used to analyze growth curves (Wirth, Funk, et al., 2023; Wirth, Rohr, et al., 2023), and the maximum specific growth rate (μmax) was derived from the OD600 measurements over time. GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used to perform all statistical analyses; the levels of significance are indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. The error bars represent standard deviations; n = 3.

Modulating the endogenous fatty acid synthesis has been proposed as a promising approach to enhance the availability of malonyl‐CoA for polyketide synthesis (Cronan & Thomas, 2009). This strategy was used in a study where synthetic antisense RNAs were employed to reduce fatty acid biosynthesis, resulting in an enrichment of the malonyl‐CoA pool in Escherichia coli. Such interventions led to a relatively modest increase in the production of 4‐hydroxycoumarin, resveratrol, and naringenin (Yang et al., 2015). Cress et al. (2015) used a CRISPathBrick tool to modulate FadR in E. coli, a transcriptional regulator that represses β‐oxidation and positively regulates fatty acid synthesis (Cronan, 2021a, 2021b), supporting a high malonyl‐CoA turnover and improved naringenin titers. In another examples based on engineered E. coli, RNA interference was directed against the transcription of fabB and fabF, encoding the β‐ketoacyl‐acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthases (KAS) I and II (Wu et al., 2014). CRISPR interference for malonyl‐CoA accumulation has also been adopted in E. coli to increase flavonoid production by targeting all possible malonyl‐CoA–related genes, with the best effects achieved via altering fabF transcription (Wu et al., 2015). Other engineering approaches have been successfully applied to various microbial hosts. For instance, several transcriptional regulators of phospholipid synthesis were manipulated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increase the production of 3‐hydroxypropionic acid (Chen et al., 2017), a platform chemical derived from malonyl‐CoA. Another elegant example is the combined engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum by deregulating the expression of genes encoding ACC components, reducing the acetyl‐CoA entry into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and eliminating anaplerotic pyruvate carboxylation, which resulted in improved production of the pentaketide noreugenin (Milke et al., 2019). E. coli and Pseudomonas taiwanensis have also been engineered using similar strategies; increased production of phloroglucinol, resveratrol, and 3‐hydroxypropionic acid, respectively, was achieved through these manipulations (Chen et al., 2024; Schwanemann et al., 2023; Zha et al., 2009).

Developing non‐traditional microbial hosts as platform strains with enhanced malonyl‐CoA supply could enable the efficient bioproduction of compounds that are challenging to produce in E. coli and other model species. Pseudomonas putida is a Gram‐negative soil bacterium (Belda et al., 2016; Calero & Nikel, 2019), which, over the years, became a biotechnological chassis (Martínez‐García & de Lorenzo, 2019; Schwanemann et al., 2020; Weimer et al., 2020). Owing to its robust and adaptable metabolism, P. putida can use a wide variety of structurally diverse molecules as carbon and energy sources (D'Arrigo et al., 2019; Fernández‐Cabezón et al., 2022; Turlin et al., 2022, 2023). This bacterium can also handle the stress induced by toxic molecules or environmental conditions (Bitzenhofer et al., 2021; Nikel & de Lorenzo, 2018; Wirth et al., 2022). P. putida has already been successfully employed as a host for the production of natural products, e.g., rhamnolipids, terpenoids, polyketides, non‐ribosomal peptides, and biopolymers—as well as other bulk and specialty chemicals (Batianis et al., 2020; de Lorenzo et al., 2024; Kozaeva et al., 2024; Prieto et al., 2016; Weimer et al., 2020; Wirth & Nikel, 2021). Pseudomonas species are efficient biopolymer producers (Mezzina et al., 2021), especially polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). PHAs comprise a large family of natural polymers that includes poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), the most widespread example of short‐chain‐length PHAs, and copolymers containing 3‐hydroxyvalerate (Steinbüchel et al., 1992) and longer carbon structures (Anderson & Dawes, 1990; Suriyamongkol et al., 2007). These bio‐based polymers emerged as an alternative to conventional plastics because they present many of the same characteristics and provide some benefits over petrochemical materials, e.g., a lower carbon footprint and more alternatives for waste disposal (Choi et al., 2020; Koller et al., 2017; Meng & Chen, 2018). As an intermediate derived from acetyl‐CoA, malonyl‐CoA directly participates in the synthesis of PHAs by supplying the key two‐carbon units that are ultimately incorporated into the polymer structure (Aduhene et al., 2021; Mitra et al., 2022). Hence, some engineering strategies to enhance PHA production have focused on increasing the intracellular concentration of malonyl‐CoA. For example, overexpressing the genes fabH Ec , fabD Ec , and fabD Ps in an engineered E. coli strain led to an increased PHA content (Taguchi et al., 1999). PHA production was also enhanced by increasing the fluxes through the CoA biosynthetic pathway, introducing a gene encoding the prokaryotic type III pantothenate kinase and supplementing pantothenate or β‐alanine as CoA precursors (Kudo et al., 2023), and by overexpressing ACC components (Wang et al., 2012). Based on these examples, we reasoned that altering malonyl‐CoA availability in P. putida could multiply the value of this host as a platform for PHA production.

In this study, we adopted a metabolic engineering approach that started by knocking‐out genes associated with glycolytic pathways, the TCA cycle, and fatty acid biosynthesis to increase the levels of malonyl‐CoA in a genome‐reduced derivative of P. putida KT2440, strain SEM11 (Wirth, Funk, et al., 2023; Wirth, Rohr, et al., 2023). A colorimetric assay, based on a repurposed polyketide synthase, was used to screen for isolates with high malonyl‐CoA content. These strains were then employed to assess PHB production from glucose through a non‐canonical PHB biosynthesis pathway, revealing a substantial enhancement in biopolymer accumulation compared to the non‐engineered, parental strain.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design, engineering, and characterization of P. putida strains with enhanced malonyl‐CoA availability

We engineered strain SEM11, a genome‐reduced variant of wild‐type P. putida KT2440, through several gene deletions in order to increase the intracellular pool of malonyl‐CoA (Figure 1A), using a well‐established method for genome engineering in Pseudomonas species based on the I‐SceI meganuclease (Martínez‐García & de Lorenzo, 2011; Wirth et al., 2020). Two genes were deleted to increase the catabolic fluxes through glycolysis: (i) hexR, encoding the transcriptional repressor that controls the expression of several glycolytic genes, including zwf‐1 (glucose 6‐phosphate dehydrogenase), the genes encoding enzymes in the Entner‐Doudoroff pathway that ultimately yield glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate and pyruvate (edd, eda, and glk), and gap‐1, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (del Castillo et al., 2007, 2008; Nikel et al., 2015), and (ii) the gcd gene, encoding the membrane‐bound glucose 2‐dehydrogenase, responsible for sugar processing via the periplasmic oxidative route (Sudarsan et al., 2014; Volke et al., 2023). The deletion of gcd has been shown to have a positive effect on both PHA accumulation (Poblete‐Castro et al., 2013) and the free CoA pool in P. putida (Gläser et al., 2020). This gene has been also targeted to increase the malonyl‐CoA content in P. taiwanensis (Schwanemann et al., 2023). In order to reduce acetyl‐CoA consumption, the gltA gene (encoding citrate synthase) was also targeted for deletion, which would prevent acetyl‐CoA from entering the TCA cycle (Figure 1A). In a previous study from our laboratory, gltA was identified as a promising candidate for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) towards increasing the availability of acetyl‐CoA in P. putida (Kozaeva et al., 2021). Furthermore, deleting this gene increased malonyl‐CoA levels in P. taiwanensis (Schwanemann et al., 2023).

Malonyl‐CoA is used in the cell mainly for fatty acid biosynthesis, and we altered the flux through this pathway by activating the transcriptionally dormant fabF‐2 gene, encoding a 3‐ketoacyl‐ACP synthase (KAS), via promoter engineering. Specifically, the medium‐strength synthetic PJ23108 promoter was integrated upstream the fabF‐2 gene (PP_3303) via homologous recombination (Martínez‐García & de Lorenzo, 2011), thereby enabling its constitutive expression. FabF‐2 is expected to display a reduced activity compared to the very active variant encoded by fabF (Dong et al., 2021). Sequence and structure comparison between FabF and FabF‐2 of P. putida KT2440 indicated that the two proteins share only 48.7% identity (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). However, the relatively high structural conservation suggests that their mechanisms may still be similar. In addition to the promoter engineering approach to activate fabF‐2, fabF was deleted to reduce the flux of malonyl‐CoA towards fatty acid synthesis (Figure 1A). Various combinations of gene deletions and transcriptional engineering led to ten engineered strains, obtained by pairing modifications in fatty acid synthesis (ΔfabF, P J23108 → fabF‐2) with deletions affecting glycolytic pathways (ΔhexR and Δgcd) or the TCA cycle (ΔgltA). These strains are SEM11 P J23108 → fabF‐2, SEM11 ΔfabF, SEM11 ΔgltA, SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF, SEM11 ΔgltA P J23108 → fabF‐2, SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF P J23108 → fabF‐2, SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd, SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd ΔfabF, SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd P J23108 → fabF‐2, and SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd ΔfabF P J23108 → fabF‐2. The native operon encoding the enzymes involved in PHA synthesis and depolymerization (de Eugenio et al., 2010) was knocked out in all these strains to avoid competition for precursors that support the accumulation of medium‐chain‐length PHAs.

We first tested whether these gene deletions were deleterious for the P. putida strains by growing the modified strains in mineral salt medium with glucose as a carbon source (Hartmans et al., 1989). Growth parameters, including maximum growth rate (μmax), extension of the lag phase, and cell density (estimated as the optical density at 600 nm, OD600), were computed with the QurvE software (Wirth, Funk, et al., 2023; Wirth, Rohr, et al., 2023). The strains containing only changes in the fatty acid synthesis and those containing a lower number of deletions had minimal variations in the growth parameters when compared to the parental SEM11 strain, whereas strains with more gene deletions showed a decrease in μmax and an increase in the extension of the lag phase (Figure 1B). The growth curves of SEM11 Δpha overlapped with that of the reference strain (SEM11, Figure 1B), suggesting that eliminating the gene cluster for PHA metabolism in P. putida has no substantial effect on the cell physiology under these conditions. All strains reached a maximum OD600 comparable to SEM11 Δpha (adopted as the reference strain henceforth, since its behavior was practically indistinguishable from that of P. putida SEM11); only SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF Δpha, SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2, and SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd P J23108 → fabF‐2 had a slight (but statistically significant) decrease in final OD600 compared to the reference strain (~3%). The most affected strains in terms of μmax were SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF Δpha and SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd P J23108 → fabF‐2, with a reduction of 41% and 43% compared to SEM11 Δpha, respectively.

These results align well with the expected perturbation of essential biochemical processes, i.e., the TCA cycle, fatty acid synthesis, and sugar processing. In particular, the gltA deletion was expected to result in several metabolic consequences that can negatively affect fitness, including reduced fluxes through the TCA cycle, an altered redox and energy metabolism, and a possible shortage of critical building‐blocks needed for synthesizing amino acids, nucleotides, and other biomass constituents (Zhou et al., 2024). A previous study from our laboratory analyzed the effect of knocking‐down the gltA gene in P. putida through a CRISPRi strategy (Kozaeva et al., 2021). A combined metabolomic and proteomic analysis showed a substantial impact on central carbon metabolism, negatively affecting some components of the EDEMP cycle (Nikel et al., 2015, 2021), the glyoxylate shunt, and enzymes involved in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis (Volke et al., 2021, 2022). The gcd deletion was also proven to cause a low rate of total carbon consumption and a reduced growth rate (Bentley et al., 2020), largely due to the role of Gcd in mediating sugar catabolism with energy conservation (Volke et al., 2023). Finally, deleting fabF in P. putida has been shown to cause a deficiency in unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (Dong et al., 2021), as FabF is responsible for extending palmitoleic acid ([9Z]‐hexadec‐9‐enoic acid, C16) to cis‐vaccenic acid ([11E]‐octadec‐11‐enoic acid, C18), a key process that affects the membrane lipid composition (Do et al., 2018). Considering these observations, the metabolic effects of the gene modifications tested herein likely account for the impact on the growth of the modified P. putida strains. Despite the slight deleterious effect of some of the gene deletions, the resulting strains are not significantly impaired under the conditions tested. After 18 h of incubation, for instance, all strains reached a comparable final OD600, confirming their suitability for applications under standard growth conditions.

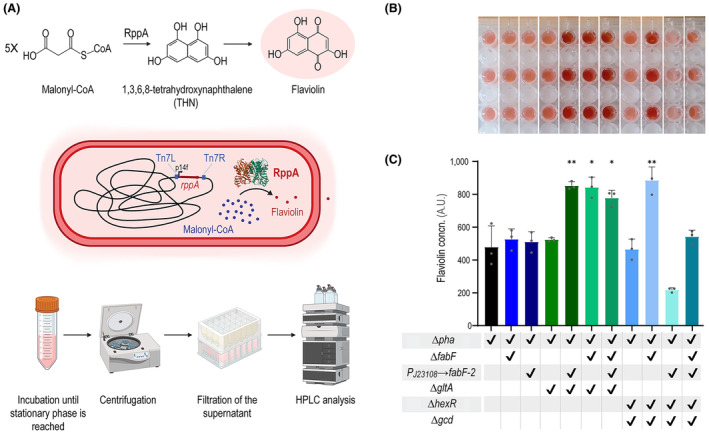

Semi‐quantitative analysis of malonyl‐CoA levels through an enzyme‐coupled biosensor

We employed an enzyme‐coupled biosensor, based on 1,3,6,8‐tetrahydroxynaphthalene synthase (RppA), for a semi‐quantitative screening of malonyl‐CoA availability in the engineered strains. RppA converts malonyl‐CoA to flaviolin (a red‐colored compound), offering a direct colorimetric readout of malonyl‐CoA levels (Figure 2A). The biosensor has been previously tested in E. coli, P. putida, and C. glutamicum, simplifying malonyl‐CoA detection through a rapid colorimetric assay (Yang et al., 2018). We integrated the rppA gene in the genome of the engineered strains using a mini‐Tn7 transposon system that allows for the incorporation of DNA constructs in the chromosome at the attTn7 attachment site that is conserved in many bacterial species (Zobel et al., 2015). The P. putida strains were transformed with two plasmids, one containing the mini‐Tn7 transposon system itself and a helper plasmid encoding the Tn7 transposase required for transposon mobilization (Schweizer & de Lorenzo, 2004). The rppA gene was constitutively expressed from the strong P14f promoter followed by the translational coupler BCD2 (Mutalik et al., 2013). We performed the integration in all engineered strains and in the reference strain SEM11 Δpha. After growing the cells under the same conditions indicated above, culture supernatants were visually inspected as a preliminary step prior to flaviolin quantification, and some of the samples displayed an intense red color, indicative of increased intracellular malonyl‐CoA (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of malonyl‐CoA levels with a biosensor. (A) A semi‐quantitative analysis of malonyl‐CoA levels in the engineered strains was carried out with an enzyme‐coupled biosensor based on the rppA gene. This gene encodes RppA, a type III polyketide synthase that converts five molecules of malonyl‐CoA into one molecule of flaviolin, which displays a red color. Malonyl‐CoA is first converted to THN by RppA (THNS), and the metabolite undergoes non‐enzymatic oxidation to flaviolin. In our design, the rppA gene was placed under the control of the constitutive P14f promoter and the module was integrated in the genome at the attTn7 site. A workflow for assessing malonyl‐CoA levels in the engineered strain is shown; this illustration was created with BioRender.com. (B) Engineered Pseudomonas putida strains endowed with enhanced malonyl‐CoA turnover were identified through a colorimetric screening method, isolating clones that displayed increased red pigmentation in the supernatant. (C) HPLC analysis was used to quantify the flaviolin produced by the different engineered strains. Arbitrary units (A.U.) indicate the intensity of the peak corresponding to flaviolin, measured at 310 nm. GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used to perform all statistical analyses; the levels of significance are indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. The error bars represent standard deviations; n = 3.

For a more precise assessment of malonyl‐CoA levels, HPLC analysis was used to directly quantify flaviolin produced by the different P. putida strains. The quantification of flaviolin is based on HPLC intensity as no flaviolin standard is available for direct quantification, limiting the possibility of reporting absolute yields. The analysis was performed after 24 h of growth, when the cultures had reached the same final OD600. As shown in Figure 2C, four strains showed significantly higher flaviolin levels than the others. The strains with the highest flaviolin production were SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd ΔfabF Δpha, SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF Δpha, SEM11 ΔgltA Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2, and SEM11 ΔgltA ΔfabF Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2. These strains had an increase in the flaviolin levels of 85%, 78%, 76%, and 63%, respectively, when compared to the reference strain. These strains harbor several gene manipulations, showing that multiple pathways need to be altered to increase malonyl‐CoA formation. Except for SEM11 ΔgltA Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2, all strains with high flaviolin production contain the fabF deletion, suggesting that targeting fatty acid synthesis has a major effect on the phenotype—yet eliminating FabF alone is not sufficient. A comparable outcome was reported for a platform P. taiwanensis strain; in this case, enhancing malonyl‐CoA availability involved a reduced demand of the thioester for fatty acid synthesis (Schwanemann et al., 2023).

Enhanced malonyl‐CoA availability supports PHB accumulation through a non‐canonical biosynthesis pathway

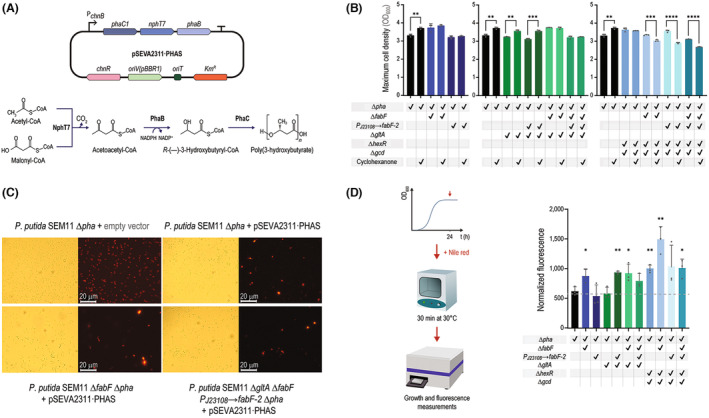

We employed a malonyl‐CoA shunt‐based pathway for PHB biosynthesis to evaluate the engineered P. putida strains for biopolymer accumulation, utilizing malonyl‐CoA as a substrate. The canonical PHB biosynthesis pathway begins with de novo acetoacetyl‐CoA formation, typically catalyzed by acetoacetyl‐CoA thiolase via a thioester‐dependent Claisen condensation between two acetyl‐CoA molecules (Choi & Lee, 1999; Nikel et al., 2006). The non‐canonical biosynthesis pathway used in our study differs in that its first step is catalyzed by NphT7, an acetoacetyl‐CoA synthase from Streptomyces sp., which irreversibly condenses acetyl‐CoA and malonyl‐CoA to produce acetoacetyl‐CoA and CoA (Okamura et al., 2010). The next two steps are mediated by PhaB and PhaC from the canonical pathway of Cupriavidus necator (Figure 3A). The topology of this non‐canonical pathway for PHB biosynthesis offers improved control over precursor availability at the acetyl‐CoA and malonyl‐CoA metabolic nodes (Orsi et al., 2021, 2022). This pathway was shown to mediate PHB accumulation from glucose in engineered P. putida (Kozaeva et al., 2021; Martínez‐García, Aparicio, et al., 2014; Martínez‐García, Nikel, et al., 2014; Nikel & de Lorenzo, 2013). A synthetic operon, comprising the genes encoding the three enzymes of the pathway, was expressed from plasmid pSEVA2311·PHAS, which carries the cyclohexanone‐inducible ChnR/P chnB expression system (Benedetti et al., 2016).

FIGURE 3.

Adopting engineered Pseudomonas putida strains for malonyl‐CoA–dependent PHA production. (A) A non‐canonical PHA biosynthesis pathway, based on NphT7 (an acetoacetyl‐CoA synthase from Streptomyces sp.), was used in this study. PhaB catalyzes the NADPH‐dependent reduction of acetoacetyl‐CoA, followed by polymerization by PhaC, a PHA synthase; both PhaB and PhaC are enzymes from C. necator. The genes encoding these three enzymes are encoded in plasmid pSEVA2311·PHAS under control of the cyclohexanone‐inducible ChnR/P chnB expression system. (B) Maximum cell density (estimated as the optical density at 600 nm, OD600) reached by the strains transformed with plasmid pSEVA2311·PHAS, in the presence or absence of the inducer (cyclohexanone). (C) Nile Red staining for visualization of PHB granules. Nile Red is a lipophilic fluorescent dye that binds to PHB granules and can be readily detected through fluorescence microscopy, offering qualitative evidence of biopolymer accumulation. (D) Nile red staining for semi‐quantitative assessment of PHB levels in engineered P. putida. Nile red was added to the cultures after 24 h of growth, when the cultures had reached stationary phase, and the fluorescence was read after 30 min of incubation. Nile red fluorescence values for each strain were normalized to the OD600 of the corresponding culture; normalized fluorescence values were compared with those of the parental strain, SEM11 Δpha. The relative fluorescence of SEM11 Δpha containing an empty pSEVA2311 vector is indicated by the dotted gray line. GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used to perform all statistical analyses; the levels of significance are indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. In all cases, the error bars represent standard deviations; n = 3.

After all strains were transformed with plasmid pSEVA2311·PHAS, we characterized their growth patterns in the presence and absence of cyclohexanone. By analyzing the growth curves of these engineered P. putida strains containing the plasmid for PHB accumulation (Figure 3B), we noticed a different physiological response to the addition of the inducer, probably due to the burden caused by the production of the pathway enzymes. In particular, virtually all strains with modifications in the TCA cycle showed a higher final cell density (OD600) in the presence of cyclohexanone. Since PHA accumulation affects light scattering and results in higher absorbance values (Martinez & Déziel, 2020), we ascribed the higher final OD600 readings to enhanced PHB accumulation. Culturing SEM11 Δpha, the reference strain, under the same conditions with increasing cyclohexanone concentrations resulted in no substantial changes in the final OD600 (data not shown). These results exclude a potential effect of the inducer on the absorbance. Most of the strains with gene deletions affecting glycolysis exhibited a lower maximum OD600, suggesting that PHB accumulation may act as a stress factor in these genetic backgrounds (Ankenbauer et al., 2020).

PHB granules within the cells were stained with Nile red, a fluorescent lipophilic dye that binds hydrophobic inclusion bodies and enables their visualization by fluorescence microscopy (Martínez‐García, Aparicio, et al., 2014; Martínez‐García, Nikel, et al., 2014; Nikel et al., 2009; Nikel, Pettinari, Galvagno, & Méndez, 2008; Nikel, Pettinari, Ramírez, et al., 2008; Spiekermann et al., 1999). Using this protocol, we obtained semi‐quantitative evidence of PHB accumulation in all engineered strains (Figure 3C). PHB granules were visualized as intensely fluorescent intracellular dots; in the negative controls, where the corresponding P. putida strain had been transformed with the empty pSEVA2311 vector (Martínez‐García et al., 2023), only the membranes were stained.

Nile red can also be used to compare PHA accumulation levels by adding the stain to cultures upon they reach stationary phase (Nikel, Pettinari, Galvagno, & Méndez, 2008; Nikel, Pettinari, Ramírez, et al., 2008). Fluorescence and OD600 are measured after a short incubation, providing a semi‐quantitative estimation of PHB content on biomass. Almost all engineered strains had significantly higher normalized fluorescence values than SEM11 Δpha harboring the empty vector (used as a negative control), except for SEM11 Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2, SEM11 ΔgltA Δpha and the reference strain SEM11 Δpha (Figure 3D). In particular, cultures of SEM11 ΔgltA Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2, SEM11 Δglta ΔfabF Δpha, and SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd ΔfabF Δpha had an increase in the normalized fluorescence of 51%, 49%, and 141%, respectively, when compared to SEM11 Δpha. We observed that the strains that exhibited high flaviolin production also performed well in PHB accumulation experiments; in fact, the two parameters showed a strong correlation across all experimental conditions and strains (Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). In general, we concluded that deleting gltA in combination with an altered fatty acid synthesis seems to favor malonyl‐CoA turnover and PHB accumulation. In contrast, deleting genes involved in glycolysis, coupled with fatty acid synthesis, appears to introduce a stress factor if combined with PHB accumulation—although the PHB content in these strains remained largely unaffected. Although the increase in Nile red fluorescence observed in the best‐performing strains validated our engineering strategy to boost malonyl‐CoA, we wanted to explore a more direct quantification method for PHB content. To this end, strain SEM11 Δglta ΔfabF Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2 was grown in shaken‐flask cultures using glucose as the main substrate, and the biomass and PHB content was determined after a 24 h incubation by methanolysis and detection of the 3‐methyl esters of 3‐hydroxybutyrate by GC‐FID (Ruiz et al., 2006). Under these conditions, this engineered strain accumulated PHB to 25.1 ± 3.9% (on a cell dry weight basis). While further experiments are necessary for a detailed comparison of all engineered strains, our findings set the basis for developing improved bioprocess for PHB production via malonyl‐CoA. Additionally, these engineered strains could serve as versatile platforms for other malonyl‐CoA‐dependent pathways and products.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this work, we identified and implemented gene deletions within different metabolic pathways that produce or consume malonyl‐CoA, obtaining engineered strains with an increased pool of intracellular malonyl‐CoA. While several metabolic pathways had to be modified and rewired simultaneously towards boosting the thioester levels, the one that seemed most influential is fatty acids synthesis. Interestingly, the engineered P. putida strains generated in this study had growth features comparable to the parental strain, yet a relatively small growth compromise was observed in glucose‐dependent cultivations—a consequence expected when genes involved in pathways essential for growth are deleted (Nogales et al., 2020). Yet, all strains reached comparable final OD600 values, making them suitable for testing PHB biosynthesis. We demonstrated that these strains could support enhanced PHB production, with SEM11 Δglta ΔfabF Δpha, SEM11 ΔhexR Δgcd ΔfabF Δpha, and SEM11 Δglta ΔfabF Δpha P J23108 → fabF‐2 as the most promising candidates for subsequent rounds of metabolic engineering to improve malonyl‐CoA–dependent production.

Several strategies have been previously explored in the context of metabolic engineering for PHA production in P. putida. Some examples include overexpressing phaJ in P. putida KCTC1639, which enhanced medium‐chain‐length PHA biosynthesis from octanoate by ~9% (Vo et al., 2008). Introducing PHA synthases from various microorganisms into P. putida KT2442 Δpha led to the accumulation of structurally diverse PHAs (Chung et al., 2009). Other approaches exploited manipulating β‐oxidation; specifically, strains with deletions in both fadBA1 and fadBA2, along with a knock‐out in phaZ (the PHA depolymerase gene), had a 20% and 100% increase in the PHA yield from p‐coumarate and lignin, respectively, as compared to the wild‐type strain (Salvachúa et al., 2020). Promoter engineering has also proven effective to boost PHA production, as demonstrated in P. putida KT2440 with modified transcription levels of phaC1 and phaC2 (the PHA synthase genes). When combined with the overexpression of genes encoding components of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and deletion of Gcd, the PHA yield on biomass was increased by 90% (Zhang et al., 2021). Unlike medium‐chain‐length PHAs, PHB biosynthesis in engineered P. putida has only been reported in a few publications (Ackermann et al., 2024; Didion et al., 2024; Kozaeva et al., 2021), and our present study indicates that malonyl‐CoA could be harnessed as a precursor for biopolymer production. However, the scalability of these strains for industrial production has yet to be demonstrated, as is the feasibility of achieving high‐yield biopolymer production under large‐scale operational conditions. To this end, multiple factors will have to be evaluated and optimized, e.g., the robustness of the strains under changing operating conditions, potential bottlenecks in metabolic fluxes and oxygen transfer, and the overall economic viability of the bioprocess (Manikandan et al., 2021). Additionally, further studies are required to understand the systems‐level impact of the genetic modifications on bacterial metabolism (Tokic et al., 2020), which could affect the productivity across extended cultivation periods and in bioreactors of different configurations. Despite these shortcomings, this study provides a foundation for optimizing malonyl‐CoA–dependent bioproduction in P. putida, a bacterial host that is gaining attention for industrial applications (de Lorenzo et al., 2024).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Giusi Favoino: Formal analysis; investigation; visualization; writing – original draft. Nicolas Krink: Investigation; methodology. Tobias Schwanemann: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Nick Wierckx: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Pablo I. Nikel: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation through grants NNF10CC1016517, NNF18CC0033664, and NNF23OC0083631 to P. I. N.

Favoino, G. , Krink, N. , Schwanemann, T. , Wierckx, N. & Nikel, P.I. (2024) Enhanced biosynthesis of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) in engineered strains of Pseudomonas putida via increased malonyl‐CoA availability. Microbial Biotechnology, 17, e70044. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.70044

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated for this work are available within the main text or upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Ackermann, Y.S. , de Witt, J. , Mezzina, M.P. , Schroth, C. , Polen, T. , Nikel, P.I. et al. (2024) Bio‐upcycling of even and uneven medium‐chain‐length diols and dicarboxylates to polyhydroxyalkanoates using engineered Pseudomonas putida . Microbial Cell Factories, 23, 54. Available from: 10.1186/s12934-024-02310-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aduhene, A.G. , Cui, H. , Yang, H. , Liu, C. , Sui, G. & Liu, C. (2021) Poly(3‐hydroxypropionate): biosynthesis pathways and malonyl‐CoA biosensor material properties. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 9, 646995. Available from: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.646995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.J. & Dawes, E.A. (1990) Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiological Reviews, 54, 450–472. Available from: 10.1128/mr.54.4.450-472.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankenbauer, A. , Schäfer, R.A. , Viegas, S.C. , Pobre, V. , Voß, B. , Arraiano, C.M. et al. (2020) Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is naturally endowed to withstand industrial‐scale stress conditions. Microbial Biotechnology, 13, 1145–1161. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.13571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batianis, C. , Kozaeva, E. , Damalas, S.G. , Martín‐Pascual, M. , Volke, D.C. , Nikel, P.I. et al. (2020) An expanded CRISPRi toolbox for tunable control of gene expression in Pseudomonas putida . Microbial Biotechnology, 13, 368–385. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.13533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda, E. , van Heck, R.G.A. , López‐Sánchez, M.J. , Cruveiller, S. , Barbe, V. , Fraser, C. et al. (2016) The revisited genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 enlightens its value as a robust metabolic chassis . Environmental Microbiology, 18, 3403–3424. Available from: 10.1111/1462-2920.13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, I. , de Lorenzo, V. & Nikel, P.I. (2016) Genetic programming of catalytic Pseudomonas putida biofilms for boosting biodegradation of haloalkanes. Metabolic Engineering, 33, 109–118. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, G.J. , Narayanan, N. , Jha, R.K. , Salvachúa, D. , Elmore, J.R. , Peabody, G.L. et al. (2020) Engineering glucose metabolism for enhanced muconic acid production in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Metabolic Engineering, 59, 64–75. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitzenhofer, N.L. , Kruse, L. , Thies, S. , Wynands, B. , Lechtenberg, T. , Rönitz, J. et al. (2021) Towards robust Pseudomonas cell factories to harbour novel biosynthetic pathways. Essays in Biochemistry, 65, 319–336. Available from: 10.1042/ebc20200173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero, P. & Nikel, P.I. (2019) Chasing bacterial chassis for metabolic engineering: a perspective review from classical to non‐traditional microorganisms. Microbial Biotechnology, 12, 98–124. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.13292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. , Zhang, Y. , Yun, J. , Zhao, M. , Zhang, C. , Chen, Z. et al. (2024) Bioproduction of 3‐hydroxypropionic acid by enhancing the precursor supply with a hybrid pathway and cofactor regeneration. ACS Synthetic Biology, 13, 3366–3377. Available from: 10.1021/acssynbio.4c00427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Yang, X. , Shen, Y. , Hou, J. & Bao, X. (2017) Increasing malonyl‐CoA derived product through controlling the transcription regulators of phospholipid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . ACS Synthetic Biology, 6, 905–912. Available from: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. & Lee, S.Y. (1999) Production of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) [P(3HB)] with high P(3HB) content by recombinant Escherichia coli harboring the Alcaligenes latus P(3HB) biosynthesis genes and the E. coli ftsZ gene. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 9, 722–725. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.Y. , Rhie, M.N. , Kim, H.T. , Joo, J.C. , Cho, I.J. , Son, J. et al. (2020) Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of polyesters: a 100‐year journey from polyhydroxyalkanoates to non‐natural microbial polyesters. Metabolic Engineering, 58, 47–81. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, A. , Liu, Q. , Ouyang, S.P. , Wu, Q. & Chen, G.Q. (2009) Microbial production of 3‐hydroxydodecanoic acid by pha operon and fadBA knockout mutant of Pseudomonas putida KT2442 harboring tesB gene. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 83, 513–519. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-009-1919-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress, B.F. , Toparlak, Ö.D. , Guleria, S. , Lebovich, M. , Stieglitz, J.T. , Englaender, J.A. et al. (2015) CRISPathBrick: modular combinatorial assembly of type II‐A CRISPR arrays for dCas9‐mediated multiplex transcriptional repression in E. coli . ACS Synthetic Biology, 4, 987–1000. Available from: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan, J.E. (2021a) The classical, yet controversial, first enzyme of lipid synthesis: Escherichia coli acetyl‐CoA carboxylase. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 85, e00032‐21. Available from: 10.1128/mmbr.00032-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan, J.E. (2021b) The Escherichia coli FadR transcription factor: too much of a good thing? Molecular Microbiology, 115, 1080–1085. Available from: 10.1111/mmi.14663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan, J.E. & Thomas, J. (2009) Bacterial fatty acid synthesis and its relationships with polyketide synthetic pathways. Methods in Enzymology, 459, 395–433. Available from: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04617-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan, J.E. & Waldrop, G.L. (2002) Multi‐subunit acetyl‐CoA carboxylases. Progress in Lipid Research, 41, 407–435. Available from: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00007-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Arrigo, I. , Cardoso, J.G.R. , Rennig, M. , Sonnenschein, N. , Herrgård, M.J. & Long, K.S. (2019) Analysis of Pseudomonas putida growth on non‐trivial carbon sources using transcriptomics and genome‐scale modelling. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 11, 87–97. Available from: 10.1111/1758-2229.12704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Eugenio, L.I. , Galán, B. , Escapa, I.F. , Maestro, B. , Sanz, J.M. , García, J.L. et al. (2010) The PhaD regulator controls the simultaneous expression of the pha genes involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism and turnover in Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Environmental Microbiology, 12, 1591–1603. Available from: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lorenzo, V. , Pérez‐Pantoja, D. & Nikel, P.I. (2024) Pseudomonas putida KT2440: the long journey of a soil‐dweller to become a synthetic biology chassis . Journal of Bacteriology, 206, e00136‐24. Available from: 10.1128/jb.00136-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Castillo, T. , Duque, E. & Ramos, J.L. (2008) A set of activators and repressors control peripheral glucose pathways in Pseudomonas putida to yield a common central intermediate. Journal of Bacteriology, 190, 2331–2339. Available from: 10.1128/JB.01726-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Castillo, T. , Ramos, J.L. , Rodríguez‐Herva, J.J. , Fuhrer, T. , Sauer, U. & Duque, E. (2007) Convergent peripheral pathways catalyze initial glucose catabolism in Pseudomonas putida: genomic and flux analysis. Journal of Bacteriology, 189, 5142–5152. Available from: 10.1128/JB.00203-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didion, Y.P. , Alván‐Vargas, M.V.G. , Tjaslma, T.G. , Woodley, J. , Nikel, P.I. , Malankowska, M. et al. (2024) A novel strategy for extraction of intracellular poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) from engineered Pseudomonas putida using deep eutectic solvents: comparison with traditional biobased organic solvents. Separation and Purification Technology, 338, 126465. Available from: 10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Do, K.H. , Park, H.M. , Kim, S.K. & Yun, H.S. (2018) Production of cis‐vaccenic acid‐oriented unsaturated fatty acid in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol . Bioprocess Engineering, 23, 100–107. Available from: 10.1007/s12257-017-0473-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H. , Ma, J. , Chen, Q. , Chen, B. , Liang, L. , Liao, Y. et al. (2021) A cryptic long‐chain 3‐ketoacyl‐ACP synthase in the Pseudomonas putida F1 unsaturated fatty acid synthesis pathway. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 297, 100920. Available from: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández‐Cabezón, L. , i Bosch, B.R. , Kozaeva, E. , Gurdo, N. & Nikel, P.I. (2022) Dynamic flux regulation for high‐titer anthranilate production by plasmid‐free, conditionally‐auxotrophic strains of Pseudomonas putida . Metabolic Engineering, 73, 11–25. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2022.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Z.L. , Gikandi, W.W. & Koffas, M.A. (2009) Increased malonyl coenzyme a biosynthesis by tuning the Escherichia coli metabolic network and its application to flavanone production. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 75, 5831–5839. Available from: 10.1128/aem.00270-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläser, L. , Kuhl, M. , Jovanovic, S. , Fritz, M. , Vögeli, B. , Erb, T.J. et al. (2020) A common approach for absolute quantification of short chain CoA thioesters in prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbes. Microbial Cell Factories, 19, 160. Available from: 10.1186/s12934-020-01413-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmans, S. , Smits, J.P. , van der Werf, M.J. , Volkering, F. & de Bont, J.A. (1989) Metabolism of styrene oxide and 2‐phenylethanol in the styrene‐degrading Xanthobacter strain 124X. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 55, 2850–2855. Available from: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2850-2855.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller, M. , Maršálek, L. , de Sousa Dias, M.M. & Braunegg, G. (2017) Producing microbial polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolyesters in a sustainable manner. New Biotechnology, 37, 24–38. Available from: 10.1016/j.nbt.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozaeva, E. , Nielsen, Z.S. , Nieto‐Domínguez, M. & Nikel, P.I. (2024) The pAblo·pCasso self‐curing vector toolset for unconstrained cytidine and adenine base‐editing in Gram‐negative bacteria. Nucleic Acids Research, 52, e19. Available from: 10.1093/nar/gkad1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozaeva, E. , Volkova, S. , Matos, M.R.A. , Mezzina, M.P. , Wulff, T. , Volke, D.C. et al. (2021) Model‐guided dynamic control of essential metabolic nodes boosts acetyl‐coenzyme A–dependent bioproduction in rewired Pseudomonas putida . Metabolic Engineering, 67, 373–386. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2021.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, H. , Ono, S. , Abe, K. , Matsuda, M. , Hasunuma, T. , Nishizawa, T. et al. (2023) Enhanced supply of acetyl‐CoA by exogenous pantothenate kinase promotes synthesis of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate). Microbial Cell Factories, 22, 75. Available from: 10.1186/s12934-023-02083-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Mu, X. , Dong, W. , Chen, Y. , Kang, Q. , Zhao, G. et al. (2024) A non‐carboxylative route for the efficient synthesis of central metabolite malonyl‐CoA and its derived products. Nature Catalysis, 7, 361–374. Available from: 10.1038/s41929-023-01103-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Mandlaa Wang, J. , Sun, Z. & Chen, Z. (2023) A strategy to enhance and modify fatty acid synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum and Escherichia coli: overexpression of acyl‐CoA thioesterases. Microbial Cell Factories, 22, 191. Available from: 10.1186/s12934-023-02189-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan, N.A. , Pakshirajan, K. & Pugazhenthi, G. (2021) Techno‐economic assessment of a sustainable and cost‐effective bioprocess for large scale production of polyhydroxybutyrate. Chemosphere, 284, 131371. Available from: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S. & Déziel, E. (2020) Changes in polyhydroxyalkanoate granule accumulation make optical density measurement an unreliable method for estimating bacterial growth in Burkholderia thailandensis . Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 66, 256–262. Available from: 10.1139/cjm-2019-0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐García, E. , Aparicio, T. , de Lorenzo, V. & Nikel, P.I. (2014) New transposon tools tailored for metabolic engineering of Gram‐negative microbial cell factories. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2, 46. Available from: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐García, E. & de Lorenzo, V. (2011) Engineering multiple genomic deletions in gram‐negative bacteria: analysis of the multi‐resistant antibiotic profile of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environmental Microbiology, 13, 2702–2716. Available from: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐García, E. & de Lorenzo, V. (2019) Pseudomonas putida in the quest of programmable chemistry. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 59, 111–121. Available from: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐García, E. , Fraile, S. , Algar, E. , Aparicio, T. , Velázquez, E. , Calles, B. et al. (2023) SEVA 4.0: an update of the standard European vector architecture database for advanced analysis and programming of bacterial phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Research, 51, D1558–D1567. Available from: 10.1093/nar/gkac1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐García, E. , Nikel, P.I. , Aparicio, T. & de Lorenzo, V. (2014) Pseudomonas 2.0: genetic upgrading of P. putida KT2440 as an enhanced host for heterologous gene expression. Microbial Cell Factories, 13, 159. Available from: 10.1186/s12934-014-0159-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught, K.J. , Kuatsjah, E. , Zahn, M. , Prates, É.T. , Shao, H. , Bentley, G.J. et al. (2023) Initiation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Metabolic Engineering, 76, 193–203. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2023.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, D.C. & Chen, G.Q. (2018) Synthetic biology of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology, 162, 147–174. Available from: 10.1007/10_2017_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina, M.P. , Manoli, M.T. , Prieto, M.A. & Nikel, P.I. (2021) Engineering native and synthetic pathways in Pseudomonas putida for the production of tailored polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnology Journal, 16, 2000165. Available from: 10.1002/biot.202000165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milke, L. , Aschenbrenner, J. , Marienhagen, J. & Kallscheuer, N. (2018) Production of plant‐derived polyphenols in microorganisms: current state and perspectives. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102, 1575–1585. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-018-8747-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milke, L. , Kallscheuer, N. , Kappelmann, J. & Marienhagen, J. (2019) Tailoring Corynebacterium glutamicum towards increased malonyl‐CoA availability for efficient synthesis of the plant pentaketide noreugenin. Microbial Cell Factories, 18, 71. Available from: 10.1186/s12934-019-1117-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milke, L. & Marienhagen, J. (2020) Engineering intracellular malonyl‐CoA availability in microbial hosts and its impact on polyketide and fatty acid synthesis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 104, 6057–6065. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-020-10643-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, R. , Xu, T. , Chen, G.Q. , Xiang, H. & Han, J. (2022) An updated overview on the regulatory circuits of polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis. Microbial Biotechnology, 15, 1446–1470. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.13915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutalik, V.K. , Guimaraes, J.C. , Cambray, G. , Lam, C. , Christoffersen, M.J. , Mai, Q.A. et al. (2013) Precise and reliable gene expression via standard transcription and translation initiation elements. Nature Methods, 10, 354–360. Available from: 10.1038/nmeth.2404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. , Chavarría, M. , Fuhrer, T. , Sauer, U. & de Lorenzo, V. (2015) Pseudomonas putida KT2440 strain metabolizes glucose through a cycle formed by enzymes of the Entner‐Doudoroff, Embden‐Meyerhof‐Parnas, and pentose phosphate pathways. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290, 25920–25932. Available from: 10.1074/jbc.M115.687749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. & de Lorenzo, V. (2013) Implantation of unmarked regulatory and metabolic modules in Gram‐negative bacteria with specialised mini‐transposon delivery vectors. Journal of Biotechnology, 163, 143–154. Available from: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. & de Lorenzo, V. (2018) Pseudomonas putida as a functional chassis for industrial biocatalysis: from native biochemistry to trans‐metabolism. Metabolic Engineering, 50, 142–155. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. , Fuhrer, T. , Chavarría, M. , Sánchez‐Pascuala, A. , Sauer, U. & De Lorenzo, V. (2021) Reconfiguration of metabolic fluxes in Pseudomonas putida as a response to sub‐lethal oxidative stress. The ISME Journal, 15, 1751–1766. Available from: 10.1038/s41396-020-00884-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. , Pettinari, M.J. , Galvagno, M.A. & Méndez, B.S. (2006) Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) synthesis by recombinant Escherichia coli arcA mutants in microaerobiosis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72, 2614–2620. Available from: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2614-2620.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. , Pettinari, M.J. , Galvagno, M.A. & Méndez, B.S. (2008) Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) synthesis from glycerol by a recombinant Escherichia coli arcA mutant in fed‐batch microaerobic cultures. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 77, 1337–1343. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-007-1255-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. , Pettinari, M.J. , Ramírez, M.C. , Galvagno, M.A. & Méndez, B.S. (2008) Escherichia coli arcA mutants: metabolic profile characterization of microaerobic cultures using glycerol as a carbon source. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, 15, 48–54. Available from: 10.1159/000111992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel, P.I. , Zhu, J. , San, K.Y. , Méndez, B.S. & Bennett, G.N. (2009) Metabolic flux analysis of Escherichia coli creB and arcA mutants reveals shared control of carbon catabolism under microaerobic growth conditions. Journal of Bacteriology, 191, 5538–5548. Available from: 10.1128/JB.00174-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales, J. , Mueller, J. , Gudmundsson, S. , Canalejo, F.J. , Duque, E. , Monk, J. et al. (2020) High‐quality genome‐scale metabolic modelling of Pseudomonas putida highlights its broad metabolic capabilities. Environmental Microbiology, 22, 255–269. Available from: 10.1111/1462-2920.14843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura, E. , Tomita, T. , Sawa, R. , Nishiyama, M. & Kuzuyama, T. (2010) Unprecedented acetoacetyl‐coenzyme a synthesizing enzyme of the thiolase superfamily involved in the mevalonate pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 11265–11270. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.1000532107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, E. , Claassens, N.J. , Nikel, P.I. & Lindner, S.N. (2021) Growth‐coupled selection of synthetic modules to accelerate cell factory development. Nature Communications, 12, 5295. Available from: 10.1038/s41467-021-25665-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, E. , Claassens, N.J. , Nikel, P.I. & Lindner, S.N. (2022) Optimizing microbial networks through metabolic bypasses. Biotechnology Advances, 60, 108035. Available from: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poblete‐Castro, I. , Binger, D. , Rodrigues, A. , Becker, J. , Martins Dos Santos, V.A.P. & Wittmann, C. (2013) In‐silico‐driven metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for enhanced production of poly‐hydroxyalkanoates. Metabolic Engineering, 15, 113–123. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak, S.W. , Abell, A.D. , Wilce, M.C. , Zhang, L. & Booker, G.W. (2012) Structure, function and selective inhibition of bacterial acetyl‐CoA carboxylase. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 93, 983–992. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-011-3796-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, M.A. , Escapa, I.F. , Martínez, V. , Dinjaski, N. , Herencias, C. , de la Peña, F. et al. (2016) A holistic view of polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism in Pseudomonas putida . Environmental Microbiology, 18, 341–357. Available from: 10.1111/1462-2920.12760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.A. , Fernández, R.O. , Nikel, P.I. , Méndez, B.S. & Pettinari, M.J. (2006) Dye (arc) mutants: insights into an unexplained phenotype and its suppression by the synthesis of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) in Escherichia coli recombinants. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 258, 55–60. Available from: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvachúa, D. , Rydzak, T. , Auwae, R. , De Capite, A. , Black, B.A. , Bouvier, J.T. et al. (2020) Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for increased polyhydroxyalkanoate production from lignin. Microbial Biotechnology, 13, 290–298. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.13481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanemann, T. , Otto, M. , Wierckx, N. & Wynands, B. (2020) Pseudomonas as versatile aromatics cell factory. Biotechnology Journal, 15, e1900569. Available from: 10.1002/biot.201900569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanemann, T. , Otto, M. , Wynands, B. , Marienhagen, J. & Wierckx, N. (2023) A Pseudomonas taiwanensis malonyl‐CoA platform strain for polyketide synthesis. Metabolic Engineering, 77, 219–230. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2023.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, H.P. & de Lorenzo, V. (2004) Molecular tools for genetic analysis of pseudomonads. In: Ramos, J.L. (Ed.) The pseudomonads: genomics, life style and molecular architecture. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, pp. 317–350. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, P. , Rehm, B.H. , Kalscheuer, R. , Baumeister, D. & Steinbüchel, A. (1999) A sensitive, viable‐colony staining method using Nile red for direct screening of bacteria that accumulate polyhydroxyalkanoic acids and other lipid storage compounds. Archives of Microbiology, 171, 73–80. Available from: 10.1007/s002030050681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbüchel, A. , Hustede, E. , Liebergesell, M. , Pieper, U. , Timm, A. & Valentin, H. (1992) Molecular basis for biosynthesis and accumulation of polyhydroxyalkanoic acids in bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 9, 217–230. Available from: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05841.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan, S. , Dethlefsen, S. , Blank, L.M. , Siemann‐Herzberg, M. & Schmid, A. (2014) The functional structure of central carbon metabolism in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80, 5292–5303. Available from: 10.1128/AEM.01643-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suriyamongkol, P. , Weselake, R. , Narine, S. , Moloney, M. & Shah, S. (2007) Biotechnological approaches for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms and plants–a review. Biotechnology Advances, 25, 148–175. Available from: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, K. , Aoyagi, Y. , Matsusaki, H. , Fukui, T. & Doi, Y. (1999) Over‐expression of 3‐ketoacyl‐ACP synthase III or malonyl‐CoA‐ACP transacylase gene induces monomer supply for polyhydroxybutyrate production in Escherichia coli HB101. Biotechnology Letters, 21, 579–584. Available from: 10.1023/A:1005572526080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tokic, M. , Hatzimanikatis, V. & Miskovic, L. (2020) Large‐scale kinetic metabolic models of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for consistent design of metabolic engineering strategies. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 13, 33. Available from: 10.1186/s13068-020-1665-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turlin, J. , Dronsella, B. , De Maria, A. , Lindner, S.N. & Nikel, P.I. (2022) Integrated rational and evolutionary engineering of genome‐reduced Pseudomonas putida strains promotes synthetic formate assimilation. Metabolic Engineering, 74, 191–205. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2022.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turlin, J. , Puiggené, Ò. , Donati, S. , Wirth, N.T. & Nikel, P.I. (2023) Core and auxiliary functions of one‐carbon metabolism in Pseudomonas putida exposed by a systems‐level analysis of transcriptional and physiological responses. mSystems, 8, e00004‐23. Available from: 10.1128/msystems.00004-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdehuesa, K.N. , Liu, H. , Nisola, G.M. , Chung, W.J. , Lee, S.H. & Park, S.J. (2013) Recent advances in the metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the production of 3‐hydroxypropionic acid as C3 platform chemical. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 97, 3309–3321. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-013-4802-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo, M.T. , Lee, K.W. , Jung, Y.M. & Lee, Y.H. (2008) Comparative effect of overexpressed phaJ and fabG genes supplementing (R)‐3‐hydroxyalkanoate monomer units on biosynthesis of mcl‐polyhydroxyalkanoate in Pseudomonas putida KCTC1639. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 106, 95–98. Available from: 10.1263/jbb.106.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volke, D.C. , Gurdo, N. , Milanesi, R. & Nikel, P.I. (2023) Time‐resolved, deuterium‐based fluxomics uncovers the hierarchy and dynamics of sugar processing by Pseudomonas putida . Metabolic Engineering, 79, 159–172. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2023.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volke, D.C. , Martino, R.A. , Kozaeva, E. , Smania, A.M. & Nikel, P.I. (2022) Modular (de)construction of complex bacterial phenotypes by CRISPR/nCas9‐assisted, multiplex cytidine base‐editing. Nature Communications, 13, 3026. Available from: 10.1038/s41467-022-30780-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volke, D.C. , Olavarría, K. & Nikel, P.I. (2021) Cofactor specificity of glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase isozymes in Pseudomonas putida reveals a general principle underlying glycolytic strategies in bacteria. mSystems, 6, e00014‐21. Available from: 10.1128/mSystems.00014-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. , Liu, C. , Xian, M. , Zhang, Y. & Zhao, G. (2012) Biosynthetic pathway for poly(3‐hydroxypropionate) in recombinant Escherichia coli . Journal of Microbiology, 50, 693–697. Available from: 10.1007/s12275-012-2234-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer, A. , Kohlstedt, M. , Volke, D.C. , Nikel, P.I. & Wittmann, C. (2020) Industrial biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida: advances and prospects. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 104, 7745–7766. Available from: 10.1007/s00253-020-10811-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, N.T. , Funk, J. , Donati, S. & Nikel, P.I. (2023) QurvE: user‐friendly software for the analysis of biological growth and fluorescence data. Nature Protocols, 18, 2401–2403. Available from: 10.1038/s41596-023-00850-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, N.T. , Gurdo, N. , Krink, N. , Vidal‐Verdú, A. , Donati, S. , Fernández‐Cabezón, L. et al. (2022) A synthetic C2 auxotroph of Pseudomonas putida for evolutionary engineering of alternative sugar catabolic routes. Metabolic Engineering, 74, 83–97. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2022.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, N.T. , Kozaeva, E. & Nikel, P.I. (2020) Accelerated genome engineering of Pseudomonas putida by I‐SceI―mediated recombination and CRISPR‐Cas9 counterselection. Microbial Biotechnology, 13, 233–249. Available from: 10.1111/1751-7915.13396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, N.T. & Nikel, P.I. (2021) Combinatorial pathway balancing provides biosynthetic access to 2‐fluoro‐cis,cis‐muconate in engineered Pseudomonas putida . Chem Catalysis, 1, 1234–1259. Available from: 10.1016/j.checat.2021.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, N.T. , Rohr, K. , Danchin, A. & Nikel, P.I. (2023) Recursive genome engineering decodes the evolutionary origin of an essential thymidylate kinase activity in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. mBio, 14, e01081‐23. Available from: 10.1128/mbio.01081-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. , Du, G. , Chen, J. & Zhou, J. (2015) Enhancing flavonoid production by systematically tuning the central metabolic pathways based on a CRISPR interference system in Escherichia coli . Scientific Reports, 5, 13477. Available from: 10.1038/srep13477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. , Yu, O. , Du, G. , Zhou, J. & Chen, J. (2014) Fine‐tuning of the fatty acid pathway by synthetic antisense RNA for enhanced (2S)‐naringenin production from L‐tyrosine in Escherichia coli . Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80, 7283–7292. Available from: 10.1128/AEM.02411-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. , Kim, W.J. , Yoo, S.M. , Choi, J.H. , Ha, S.H. , Lee, M.H. et al. (2018) Repurposing type III polyketide synthase as a malonyl‐CoA biosensor for metabolic engineering in bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115, 9835–9844. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.1808567115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. , Lin, Y. , Li, L. , Linhardt, R.J. & Yan, Y. (2015) Regulating malonyl‐CoA metabolism via synthetic antisense RNAs for enhanced biosynthesis of natural products. Metabolic Engineering, 29, 217–226. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha, W. , Rubin‐Pitel, S.B. , Shao, Z. & Zhao, H. (2009) Improving cellular malonyl‐CoA level in Escherichia coli via metabolic engineering. Metabolic Engineering, 11, 192–198. Available from: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Liu, H. , Liu, Y. , Huo, K. , Wang, S. , Liu, R. et al. (2021) A promoter engineering‐based strategy enhances polyhydroxyalkanoate production in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 191, 608–617. Available from: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Zhang, Y. , Long, C.P. , Xia, X. , Xue, Y. , Ma, Y. et al. (2024) A citric acid cycle‐deficient Escherichia coli as an efficient chassis for aerobic fermentations. Nature Communications, 15, 2372. Available from: 10.1038/s41467-024-46655-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zobel, S. , Benedetti, I. , Eisenbach, L. , de Lorenzo, V. , Wierckx, N.J.P. & Blank, L.M. (2015) Tn7‐based device for calibrated heterologous gene expression in Pseudomonas putida . ACS Synthetic Biology, 4, 1341–1351. Available from: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated for this work are available within the main text or upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.