Abstract

Background

Patients with high-risk localized and locally advanced prostate cancer (HR-LPC/LAPC) have increased risk of metastasis, leading to reduced survival rates. Segmenting the disease course [time to recurrence, recurrence to metastasis, and post-metastasis survival (PMS)] may identify disease states for which the greatest impacts can be made to ultimately improve survival.

Objective

Evaluate real-world PMS of patients with HR-LPC/LAPC who received primary radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiotherapy (RT) with or without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Patients and Methods

Electronic health records from an oncology database were used to assess PMS. Risk of death was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Hazard ratios (HRs) were used to analyze the impact of treatment and time to metastasis (TTM) on PMS. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were calculated for patients with HR-LPC/LAPC versus the US general male population.

Results

Overall, 5008 patients with HR-LPC/LAPC were identified, and 1231 developed metastases after primary treatment (RP, n = 885; RT only, n = 262; RT+ADT, n = 84). Age-adjusted PMS HR between the RP and RT only cohorts was 1.19 (p = 0.077) and between RP and RT+ADT cohorts was 1.32 (p = 0.078). TTM was unrelated to PMS in unadjusted (HR 1.01, p = 0.2) and age-adjusted models (HR 0.99, p = 0.3). Relative to pre-metastasis SMRs, post-metastasis SMRs increased eightfold and fivefold in patients treated with RP and RT±ADT, respectively.

Conclusions

PMS was unrelated to TTM in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC, suggesting PMS may be independent of the trajectory to development of metastases. Given PMS may be a fixed length of time, delaying the development of metastasis may improve survival in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11523-024-01113-5.

Key Points

| This real-world study evaluated the post-metastasis survival (PMS) of a cohort of patients in the USA with high-risk localized and locally advanced prostate cancer (HR-LPC/LAPC) who received primary treatment with radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy. |

| Among patients who developed metastases, PMS was not associated with the time to metastatic disease. This finding suggests that PMS is a fixed time interval and that delaying the development of metastasis will improve survival in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC receiving primary treatment with either radiotherapy or surgery. |

| Future research should examine treatment modalities that may delay metastatic disease development in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC. |

Introduction

High-risk localized and locally advanced prostate cancer (HR-LPC/LAPC) accounts for approximately 15% of newly diagnosed prostate cancer cases in the USA [1]. There are several definitions of high-risk prostate cancer in literature [2, 3]. The traditional D’Amico group classification, which is based on measures that are easily accessible to the treating physician, defines high-risk prostate cancer as clinical T stage 2c, Gleason score of at least 8, or a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of ≥ 20 ng/mL [4]. Although there is no universal definition of LAPC, the criterion cT3-4 or clinically node-positive (cN+) has been suggested [2]. Patients with HR-LPC/LAPC are at increased risk of PSA failure, metastatic disease, and death [5–7]. The standard-of-care treatment options in this patient group are radical prostatectomy (RP), with or without pelvic lymph node dissection, or radiotherapy (RT) with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [7]. However, consensus on the optimal treatment strategy in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC has not been established [8]. Importantly, these treatment modalities do not eliminate the risk of disease progression, and patients may require salvage treatment for local recurrence or systemic therapy for biochemical recurrence or metastatic disease [7, 8].

Recently, the Intermediate Clinical Endpoints in Cancer of the Prostate (ICECaP) working group showed that metastasis-free survival (MFS), defined as metastasis on conventional imaging or death from any cause, is a strong surrogate for overall survival (OS) among patients with LPC [9, 10]. Additionally, studies in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC have reported MFS, OS, and prostate cancer–specific survival outcomes in those treated with RP versus RT plus ADT [11–16]. Although survival outcomes of patients with metastatic prostate cancer have been studied extensively [17–19], metastatic prostate cancer includes a heterogenous group of patients with de novo metastases and those with localized disease who later progressed to metastases [20]. Consequently, there are limited data on the impact of treatment on the post-metastasis survival (PMS) period in specific subgroups of patients with prostate cancer. Breaking down the disease course into time from treatment to recurrence, recurrence to metastases, and PMS, may identify where in the disease trajectory therapeutic interventions have the potential to confer the greatest survival benefit.

New adjuvant/neoadjuvant treatment modalities aiming to postpone metastases are actively being studied for patients with HR-LPC/LAPC, but long-term PMS evidence is lacking. Therefore, characterizing how the path to metastases influences mortality in these patients may help to quantify the lifetime benefits of new treatment modalities. There is a need to better understand the change in risk of death, not only from HR-LPC/LAPC to metastatic disease but also post-metastasis, and whether the time from primary treatment to metastasis impacts the PMS of this patient group.

In this retrospective, observational study, we used a comprehensive dataset with information spanning 22 years to evaluate the PMS of patients with HR-LPC/LAPC who received primary treatment with RP, RT only, or RT + ADT before developing metastatic disease.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This retrospective, observational study used information from the ConcertAI Patient360TM oncology database [21], which has been previously used for cancer research [22]. The database comprises de-identified electronic medical record data with comprehensive information on demographics, prescribed and administered medications, coded diagnoses [using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10-CM or SNOMED-CT codes], and procedures.

The database includes a prostate data product comprising a random sample of patients with prostate cancer who were initially screened using the ICD-10-CM code C61 and ICD-9-CM code 185. Patients with metastatic disease (staging classification of 4B or M1) were identified. If staging information was not available, patients with documented sites of metastases that qualified as distant (excluding locations such as bladder, urinary organs, and pelvis) were identified as having metastatic disease. All patients were subsequently confirmed to have the appropriate diagnosis by a curation process that uses information available within patient documents. Human curation processes were used where information was extracted from unstructured data sources, such as provider notes, pathology, and imaging reports. The curation processes were supported by computer natural language processing to produce usable datasets based on clinical attributes, D’Amico criteria, health economics/outcomes research, and epidemiological peer-reviewed literature [21]. Approximately 80% of the patients in the dataset were from community oncology clinics, and the remaining 20% were from urology-affiliated practices, including those aligned with oncology groups and urology practices within an extended network/healthcare system. Thus, a large proportion of these patients were seen by a medical oncologist, resulting in a heavy data skew toward patients with higher-risk prostate cancer or metastatic disease that needed systemic therapy. All data were de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, and thus no institutional review board approval was required. Supplementary Materials include additional results from earlier analyses on a related dataset, which encompassed the current study cohort plus additional patients. These analyses complement the study findings presented here.

Cohort Selection

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with prostate cancer were identified from the ConcertAI Patient360TM Prostate Cancer dataset between January 2000 and October 2022. A patient’s prostate cancer was defined as HR-LPC/LAPC when one of the following D’Amico criteria was met: clinical T stage 2c, Gleason score of at least 8, or PSA level ≥ 20 ng/mL. The earliest date that a patient met one of the criteria was used to define the date of HR-LPC/LAPC. Patients were excluded if they had metastatic disease (M1) at diagnosis or if they had other primary cancers. The cohorts only included cases where the date of HR-LPC/LAPC occurred from 30 days before the prostate cancer diagnosis date to the date of diagnosis of metastases. Patients with HR-LPC/LAPC were then categorized in mutually exclusive groups for analysis based on primary treatment: RP, RT only, and RT + ADT when ADT (i.e., gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone agonist or antagonist: leuprolide, goserelin, triptorelin, histrelin, degarelix, relugolix, or estrogens) was given within 180 days before or after RT. Patients who received RT only were included as a separate group.

Study Outcome Definitions

Pre-metastasis survival was defined as the time from treatment to either death or censoring at the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease, or the date of last activity for patients without a recorded date of death or metastatic disease. PMS was defined as the time from diagnosis of metastatic disease to either death or censoring at the date of last activity for patients without a recorded date of death. Time to metastasis (TTM) was defined as the time from the start of treatment to the date of metastatic disease diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were used to describe baseline patient characteristics for RP, RT only, or RT + ADT groups. Continuous variables were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), and categorical variables presented as counts and percentages. Pre-metastasis survival and PMS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Among those who developed metastases, Cox proportional-hazard regression models were used to analyze the impact of the primary treatment modality on PMS and the effect of TTM on PMS, with adjustment for patient age at metastasis (treated as a continuous variable). The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated along with hazard ratios. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were calculated as the ratio of the observed 5-year mortality rate in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC treated with RP, RT only, or RT + ADT to the age-weighted mortality rate for the general male population in the USA [23]. Age-weighted mortality rates in 2020 for the general male population in the USA were computed using the proportion of individuals in each age group of the reference study sample [23]. All tests were two-sided, and p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. The data extraction and manipulation, statistical analyses, and output generation of this study were done using SQL Workbench (version 14.0.2) and R (version 4.2.2).

Results

Patient Cohorts

A total of 10,679 patients with prostate cancer were identified, and 47% (5008/10,679) were classified as having HR-LPC/LAPC per D’Amico criteria (Fig. 1). Of these, 2627 had no treatment documented in their medical records or had received treatment other than RP, RT only, or RT + ADT (e.g., primary ADT alone). The resulting pre-metastasis cohort comprised 2381 patients with HR-LPC/LAPC who received RP (n = 1696), RT only (n = 421), or RT + ADT (n = 264) as the primary treatment. Among patients who received primary treatment with RT, 39% (264/685) received concomitant ADT. Patients who received RT only (61%, 421/685) were included as a separate group. Overall, 1231 of 2381 patients with HR-LPC/LAPC developed metastatic disease after primary treatment with RP (52%, 885/1696), RT only (62%, 262/421), or RT + ADT (32%, 84/264) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient cohorts. ADT androgen deprivation therapy, HR-LPC/LAPC high-risk localized or locally advanced prostate cancer, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the pre-metastasis cohort

| Pre-metastasis cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | RP | RT only | RT + ADT | |

| N | 2381 | 1696 | 421 | 264 |

| Median age at primary treatment (IQR), years | 64.0 (58.0–69.0) | 63.0 (57.0–68.0) | 67.0 (60.0–72.0) | 70.0 (64.0–75.0) |

| Developed metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| M0 | 1149 (48) | 811 (48) | 158 (38) | 180 (68) |

| M1 | 1232 (52) | 885 (52) | 263 (62) | 84 (32) |

| Median follow-up (IQR), years | 7.5 (4.0–12.7) | 8.4 (4.6–13.4) | 7.9 (4.2–12.4) | 3.7 (2.0–6.4) |

| CCI at prostate cancer diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| 1–2 | 626 (26) | 388 (23) | 142 (34) | 96 (36) |

| 3–4 | 31 (1.3) | 18 (1.1) | 5 (1.2) | 8 (3.0) |

| ≥ 5 | 29 (1.2) | 23 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.9) |

| Missing or 0 | 1695 (71) | 1267 (75) | 273 (65) | 155 (59) |

| ECOG PS at prostate cancer diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 274 (12) | 136 (8.0) | 39 (9.3) | 99 (38) |

| 1–2 | 81 (3.4) | 36 (2.1) | 14 (3.3) | 31 (12) |

| ≥ 3 | 5 (0.2) | 1 (< 0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| Missing | 2021 (85) | 1523 (90) | 367 (87) | 131 (50) |

ADT androgen deprivation therapy, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, IQR interquartile range, M metastatic status, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics of the pre-metastasis and post-metastasis cohorts are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In the total pre-metastasis cohort, the median [interquartile range (IQR)] age at primary treatment for patients with HR-LPC/LAPC was 64.0 (58.0–69.0) years. Patients who received primary treatment with RP were younger than patients treated with RT only or RT + ADT, at both the time of primary treatment and the time of metastasis. The median (IQR) duration of follow-up in the pre-metastasis and post-metastasis cohorts was 7.5 (4.0–12.7) years and 2.9 (1.4–4.5) years, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Among those who developed metastases (n = 1231), the median (IQR) time from primary treatment to metastasis was longer for patients treated with RP [5.5 (2.6–9.8) years] than for patients treated with RT only [4.2 (2.6–8.7) years] or RT + ADT [2.9 (1.6–4.5) years] (Table 2). There was a high level of missingness in the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), disease volume, castration resistance, and biochemical recurrence data fields. Patient characteristics in the related dataset are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in the post-metastasis cohort

| Post-metastasis cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | RP | RT only | RT + ADT | |

| N | 1231 | 885 | 262a | 84 |

| Median age at primary treatment (IQR), years | 64.0 (58.0–69.0) | 63.0 (57.0–68.0) | 67.0 (60.0–72.0) | 70.0 (64.0–75.0) |

| Median age at metastasis (IQR), years | 70.0 (65.0–76.0) | 69.0 (64.0–75.0) | 73.0 (66.0–78.0) | 73.0 (67.0–77.0) |

| Median time from primary treatment to metastasis (IQR), years | 4.9 (2.5–9.1) | 5.5 (2.6–9.8) | 4.2 (2.6–8.7) | 2.9 (1.6–4.5) |

| Metastasis year, n (%) | ||||

| ≤ 2006 | 13 (1.1) | 11 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2007–2011 | 102 (8.3) | 73 (8.2) | 24 (9.2) | 5 (6.0) |

| 2012–2016 | 532 (43) | 373 (42) | 131 (50) | 28 (33) |

| ≥ 2017 | 584 (47) | 428 (48) | 105 (40) | 51 (61) |

| Median follow-up (IQR), years | 2.9 (1.4–4.5) | 2.9 (1.5–4.7) | 2.7 (1.2–4.4) | 2.3 (1.0–3.8) |

| CCI at prostate cancer diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| 1–2 | 370 (30) | 243 (27) | 96 (37) | 31 (37) |

| 3–4 | 19 (1.5) | 13 (1.5) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (2.4) |

| ≥ 5 | 14 (1.1) | 11 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.4) |

| Missing or 0 | 828 (67) | 618 (70) | 161 (61) | 49 (58) |

| CCI at metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| 1–2 | 168 (14) | 107 (12) | 42 (16) | 19 (23) |

| 3–4 | 18 (1.5) | 10 (1.1) | 6 (2.3) | 2 (2.4) |

| ≥ 5 | 9 (0.7) | 7 (0.8) | 0 | 2 (2.4) |

| Missing or 0 | 1036 (84) | 761 (86) | 214 (82) | 61 (73) |

| ECOG PS at prostate cancer diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 | 79 (6.4) | 32 (3.6) | 17 (6.5) | 30 (36) |

| ≥ 2 | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Missing | 1149 (93) | 851 (96) | 244 (93) | 54 (64) |

| ECOG PS at metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 | 673 (55) | 491 (55) | 127 (48) | 55 (65) |

| ≥ 2 | 58 (4.7) | 32 (3.6) | 23 (8.8) | 3 (3.6) |

| Missing | 500 (41) | 362 (41) | 112 (43) | 26 (31) |

ADT androgen deprivation therapy, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, IQR interquartile range, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy

aOne patient from the RT only group pre-metastasis cohort was dropped because survival time was registered as zero

Post-Metastasis Survival

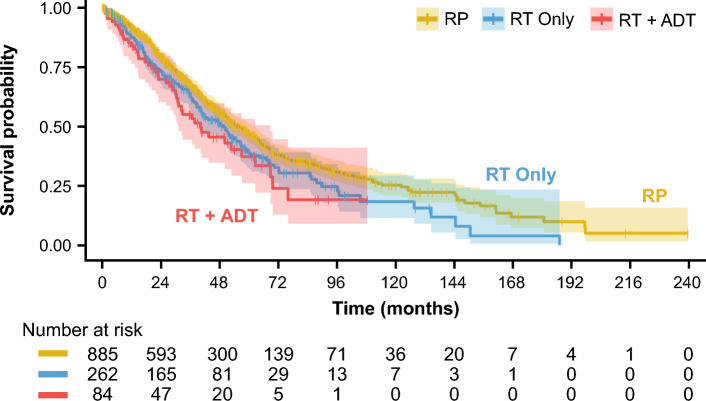

Among those who developed metastases (n = 1231), PMS was estimated based on primary treatment received at the time of HR-LPC/LAPC identification. Overall, median (IQR) PMS was 52.6 (50.0–57.6) months. The median (IQR) PMS favored primary treatment with RP [54.9 (51.3–62.5) months] compared with RT only [49.8 (40.4–56.8) months] and RT + ADT [40.1 (30.9–68.8) months] (Table 3, Fig. 2). After adjusting for age at metastasis diagnosis, PMS hazard ratio of patients treated with RP versus those treated with RT only was 1.19 (p = 0.077) and PMS hazard ratio of patients treated with RP versus those treated with RT + ADT was 1.32 (p = 0.078) (Table 4). Further adjustment for LAPC versus HR-LPC status in the related dataset (Table S3) did not significantly alter the relationship between primary treatment and PMS (Table S4). To further understand the disease trajectory of HR-LPC/LAPC, we estimated the association of TTM and PMS. TTM was unrelated to PMS in both the unadjusted [hazard ratio 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00–1.03, p = 0.2] and age-adjusted Cox regression models (hazard ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–1.01, p = 0.3) (Table 5, Table S5). Additional adjustment for primary treatment (RP, RT only, RT + ADT), LAPC versus HR-LPC status, and subsequent treatments received (Table S6) had no impact on the relationship between TTM and PMS (hazard ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.97–1.01) (Table S7).

Table 3.

PMS by primary treatment among those who developed metastasis

| Total | RP | RT only | RT + ADT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1231 | 885 | 262 | 84 |

| PMSa | ||||

| Death, n (%) | 634 (51.5) | 444 (50.1) | 146 (55.7) | 44 (52.3) |

| Median survival (IQR), months | 52.6 (50.0–57.6) | 54.9 (51.3–62.5) | 49.8 (40.4–56.8) | 40.1 (30.9–68.8) |

ADT androgen deprivation therapy, HR-LPC/LAPC high-risk localized and locally advanced prostate cancer, IQR interquartile range, PMS post-metastasis survival, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy

aPMS was estimated at the time of treatment for HR-LPC/LAPC

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing PMS of patients with HR-LPC/LAPC treated with RP, RT only, and RT + ADT. Shaded area represents 95% confidence interval. ADT androgen deprivation therapy, HR-LPC/LAPC high-risk localized and locally advanced prostate cancer, PMS post-metastasis survival, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between primary treatment type and PMS among those who developed metastasis

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| HR-LPC/LAPC with RP vs | ||||

| RT only | 1.26 (1.04–1.52) | 0.016 | 1.19 (0.98–1.43) | 0.077 |

| RT + ADT | 1.47 (1.08–2.00) | 0.016 | 1.32 (0.97–1.81) | 0.078 |

| Age at metastasis, years | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 |

ADT androgen deprivation therapy, CI confidence interval, HR-LPC/LAPC high-risk localized or locally advanced prostate cancer, PMS post-metastasis survival, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between TTM and PMS among those who developed metastasis

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Time from primary treatment to metastasis, years | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.2 | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.3 |

| Age at metastasis, years | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.001 |

CI confidence interval, PMS post-metastasis survival, TTM time to metastasis

Five-Year Pre- and Post-Metastasis Risk of Death

The 5-year mortality rates for patients treated with RP were lower than for those treated with RT only or with RT + ADT (Table 6). The 5-year pre-metastasis SMR was 0.50 (95% CI 0.39–0.62) in patients treated with RP and 0.72 (95% CI 0.55–0.91) in those treated with RT with or without ADT. The 5-year SMRs were lower than one, indicating that the weighted mortality rate for patients with HR-LPC/LAPC was lower than the general male population in the USA.

Table 6.

Five-year mortality rates, age-weighted US mortality rates, and SMRs in patients with HR-LPC/LAPC treated with RP or RT ± ADT

| 5-year mortality rate and SMR (95% CI) | RP | RT ± ADT |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-metastasis | ||

| Patient cohort mortality | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) | 0.08 (0.06–0.11) |

| Age-weighted US mortality | 0.08 (0.08–0.08) | 0.11 (0.11–0.12) |

| Pre-metastasis SMR | 0.50 (0.39–0.62) | 0.72 (0.55–0.91) |

| Post-metastasis | ||

| Patient cohort mortality | 0.53 (0.50–0.57) | 0.61 (0.55–0.67) |

| Age-weighted US mortality | 0.14 (0.14–0.14) | 0.17 (0.16–0.17) |

| Post-metastasis SMR | 3.86 (3.62–4.11) | 3.71 (3.32–4.07) |

| Ratio of pre- to post-metastasis | 7.76 (6.16–9.93) | 5.14 (3.97–6.84) |

ADT androgen deprivation therapy, CI confidence interval, HR-LPC/LAPC high-risk localized or locally advanced prostate cancer, RP radical prostatectomy, RT radiotherapy, SMR standardized mortality ratio

In contrast, the 5-year post-metastasis SMR values were much higher than 1, implying a much higher risk of death after metastases relative to the general male population in the United States. Nonetheless, SMRs were similar in patients treated with RP (3.86, 95% CI 3.62–4.11) or RT with or without ADT (3.71, 95% CI 3.32–4.07). Relative to the pre-metastasis period, SMR values after metastasis increased eightfold in patients treated with RP, and fivefold in patients treated with RT with or without ADT.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first real-world study evaluating PMS of patients with HR-LPC/LAPC. Importantly, PMS was unrelated to TTM or primary treatment (age-adjusted), suggesting that PMS may be a fixed time interval, independent of the factors promoting, or time it takes to develop, metastatic disease. Our finding that PMS is independent of TTM is consistent with the findings of the ICECaP working group, who report strong surrogacy for MFS and OS among patients with LPC [9, 10]. Overall, these results suggest that the most meaningful way to improve survival of patients with HR-LPC/LAPC is to delay or prevent the development of metastases.

The PMS of the post-metastasis cohort included in our study is similar to the post-metastasis prostate cancer-specific survival reported by a previous real-world evidence study by Pascale et al. [24]. Using a database of 1364 patients with prostate cancer, Pascale et al. examined prostate cancer-specific survival after metastasis, defined as the time interval from the date of the first radiographic metastasis to the date of prostate cancer-related death or the last follow-up. Among 913 patients who presented with LPC and underwent curative treatment, 136 developed metastatic hormone-sensitive disease and had a median prostate cancer-specific survival of 50.4 (95% CI 39.1–78.5) months [24]. The similar PMS across study populations suggests that PMS is a relative constant time interval.

As expected, the risk of death increased significantly after metastasis. However, our findings provide new insights into the magnitude of change in risk of death from the pre- to post-metastasis disease states: in patients who were treated with RP or RT with or without ADT, the relative risk of death increased by eightfold and fivefold after metastasis, respectively. Notably, despite patients with HR-LPC/LAPC being at increased risk of metastases and death, the overall SMR values among the pre-metastasis cohort were lower than those in the general US male population. A similar observation was reported for a consecutive series of patients with LPC treated with RP, who had an SMR below 1 compared with an age-matched background population [25]. Røder et al. surmised that this result might reflect selection bias, including low comorbidity, long life expectancy, and higher socioeconomic status of patients who are eligible for primary treatment [25]. Among patients who developed metastases after primary treatment for HR-LPC/LAPC, RP was associated with improved PMS compared with RT only and RT + ADT. Although after accounting for age at metastasis diagnosis the results suggest independence between primary treatment and PMS, other important baseline characteristics, such as ECOG PS and CCI, could not be accounted for due to the high level of missing data. Thus, caution is required when interpreting these results.

Our findings have important implications for optimizing the OS of patients with HR-LPC/LAPC. There is some evidence that treatment intensification with androgen receptor pathway inhibitors may improve outcomes in patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer. In an exploratory pooled clinical trial analysis that included 72 patients with intermediate- and high-risk disease, neoadjuvant therapy with abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide before RP was shown to potentially have a positive impact on time to biochemical recurrence rates [26]. In the EMBARK phase 3 trial [27], 1068 patients with prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence after local therapy were randomized to receive enzalutamide + ADT, ADT alone, or enzalutamide alone, and followed for a median of 60.7 months. Results showed that patients treated with enzalutamide + ADT or enzalutamide monotherapy had improved MFS compared with those who were treated with ADT alone. The STAMPEDE trial demonstrated that treatment with abiraterone acetate + prednisolone + ADT was associated with improved OS compared with ADT alone in patients with HR-LAPC or metastatic prostate cancer [28]. Apalutamide is currently being evaluated for the treatment of HR-LPC/LAPC before RP and concurrent with RT in the PROTEUS (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03767244) and ATLAS (NCT02531516) phase 3 trials, respectively. Similarly, enzalutamide is being evaluated with concurrent RT in the ENZARAD trial (NCT02446444).

Interventions that focus on diet and lifestyle may also potentially delay the development of metastasis. In patients with prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence after local treatment, a low-carbohydrate diet may be associated with a longer PSA doubling time [29]. There is also evidence of a link between obesity and prostate cancer-specific death [30], suggesting that obesity may be associated with a more aggressive form of prostate cancer [31], giving rise to the possibility that weight-loss interventions may also delay metastatic spread, although this requires formal testing.

Limitations of the current study reflect those that are inherent to the use of administrative databases for epidemiological research, including the dependency of the accuracy of ICD codes and algorithms to identify medical conditions, missing or imprecise event dates, and the retrospective design with nonrandom assignment of patients to primary treatment groups. Although the duration of ADT may impact the time to metastasis, ADT treatment duration could not be estimated owing to missingness of the ADT end date. The use of androgen receptor pathway inhibitors among patients with metastatic disease is likely to impact PMS; however, sufficient data on the use of these agents were not available in this study. Additionally, the patient cohorts included in this study were from the USA, so the findings may not be generalizable to patients globally. For example, there are differences between the USA and other countries in both policies and healthcare practices that impact prostate cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Moreover, as noted above, all patients in this study were seen by medical oncology providers; thus, the data were heavily skewed toward higher-risk patients and those who needed systemic therapy, which likely explains the very high (> 50%) rate of metastases.

In addition, relevant patient prognostic factors, such as ECOG PS, were not available from the database used for this study, which hindered a full multivariate analysis, and data were also not available to estimate the proportion of patients in the post-metastasis cohort who had mCSPC or mCRPC. Other potential confounders, such as the distribution of risk factors at diagnosis and subsequent therapies received pre-metastasis, were explored in a related dataset as shown in the Supplementary Materials; however, these seem to suggest minimal impact on the key research findings. Despite this, these analyses should be interpreted with caution as the related dataset differs slightly from the cohorts described herein due to the inclusion of additional patients. As such, future research should explore data sources with higher urology and radiation oncology practice representation and detailed information on prognostic factors, including ECOG PS, CCI, disease volume, whether the disease after metastasis is mCSPC or mCRPC, number of risk factors present at baseline, and the subsequent treatments and therapies after metastasis.

Conclusions

This real-world study demonstrated that among patients with HR-LPC/LAPC who developed metastases, PMS was not associated with TTM, suggesting that PMS is a fixed time interval. This suggests that OS may be improved with targeted therapeutic strategies that reduce the risk of developing metastasis for patients with HR-LPC/LAPC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Ann Tighe, PhD, and Laura Graham, PhD, of Parexel and was funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC

Declarations

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium. This study was funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC. The sponsor was involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation and review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

S.J.F. has had consulting or advisory roles for Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Janssen Biotech, Merck, Myovant Sciences, Pfizer, and Sanofi; has received compensation for travel from Sanofi; and has had speakers bureau roles for Astellas, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi. L.F. is employed by Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V. F.D.S. is an employee of Janssen Global Services, LLC, and may hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. N.B. is employed by Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V. and may hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. S.D.M., S.A.M., D.L., L.Y., and F.P. are employed by Janssen Research and Development and may hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. C.M. has received payment or honoraria from HMP Global Great Debates and Updates in Genitourinary Oncology; and has received compensation for travel from European Association of Urology.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable. All data were de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, and thus no institutional review board approval was required.

Consent to Publish

No patient-identifying information is included in this article; therefore, consent to publish was not required.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Data Availability

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinicaltrials/transparency. These data were made available by ConcertAI, Cambridge, MA, and used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Other researchers should contact ConcertAI, Real-World Data Products: https://www.concertai.com/data-products.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the design and conduct of the study, had access to the data, drafted the manuscript with input from the sponsor (Janssen), reviewed and approved the manuscript before submission, made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this work. S.J.F. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Carroll PR. Time trends and local variation in primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1117–23. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2021;79(2):243–62. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, Chen RC, Crispino T, Fontanarosa J, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol. 2018;199(3):683–90. 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, Broderick GA, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280(11):969–74. 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKay RR, Feng FY, Wang AY, Wallis CJD, Moses KA. Recent advances in the management of high-risk localized prostate cancer: local therapy, systemic therapy, and biomarkers to guide treatment decisions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:e241–52. 10.1200/EDBK_279459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao G, Li Y, Wang J, Wu X, Zhang Z, Zhanghuang C, et al. Gleason score, surgical and distant metastasis are associated with cancer-specific survival and overall survival in middle aged high-risk prostate cancer: a population-based study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1028905. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1028905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Association of Urology. Guidelines on prostate cancer. 2023. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/. Accessed 23 October 2023.

- 8.Reina Y, Villaquirán C, García-Perdomo HA. Advances in high-risk localized prostate cancer: staging and management. Curr Probl Cancer. 2023;47(4): 100993. 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2023.100993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie W, Regan MM, Buyse M, Halabi S, Kantoff PW, Sartor O, et al. Metastasis-free survival is a strong surrogate of overall survival in localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(27):3097–104. 10.1200/jco.2017.73.9987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ICECaP Working Group, Sweeney C, Nakabayashi M, Regan M, Xie W, Hayes J, et al. The development of intermediate clinical endpoints in cancer of the prostate (ICECaP). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(12):djv261. 10.1093/jnci/djv261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Markovina S, Meeks MW, Badiyan S, Vetter J, Gay HA, Paradis A, et al. Superior metastasis-free survival for patients with high-risk prostate cancer treated with definitive radiation therapy compared to radical prostatectomy: a propensity score-matched analysis. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):190–6. 10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, Metcalfe C, Davis M, Turner EL, et al. Fifteen-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(17):1547–58. 10.1056/NEJMoa2214122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ennis RD, Hu L, Ryemon SN, Lin J, Mazumdar M. Brachytherapy-based radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy are associated with similar survival in high-risk localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1192–8. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.9134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih HJ, Chang SC, Hsu CH, Lin YC, Hung CH, Wu SY. Comparison of clinical outcomes of radical prostatectomy versus IMRT with long-term hormone therapy for relatively young patients with high- to very high-risk localized prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(23):5986. 10.3390/cancers13235986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg S, Cole AP, Krimphove MJ, Nabi J, Marchese M, Lipsitz SR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of radical prostatectomy versus external beam radiation therapy plus brachytherapy in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;75(4):552–5. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallis CJD, Saskin R, Choo R, Herschorn S, Kodama RT, Satkunasivam R, et al. Surgery versus radiotherapy for clinically-localized prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016;70(1):21–30. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, Chung BH, Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, et al. Apalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: final survival analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase III TITAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(20):2294–303. 10.1200/JCO.20.03488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen YH, Carducci MA, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Hahn NM, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: Long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1080–7. 10.1200/jco.2017.75.3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishan AU, Sun Y, Hartman H, Pisansky TM, Bolla M, Neven A, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy use and duration with definitive radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(2):304–16. 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haffner MC, Zwart W, Roudier MP, True LD, Nelson WG, Epstein JI, et al. Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(2):79–92. 10.1038/s41585-020-00400-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ConcertAI Data Products Team ConcertAI data products manual. Patient360 (solid tumors). Cambridge, MA: ConcertAI; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao P, Tepsick JG, Walker B, Ray HE. Improving real-world mortality data quality in oncology research: augmenting electronic medical records with obituary, Social Security death index, and commercial claims data. JCO Clin Cancer Inf. 2023;7: e2300014. 10.1200/CCI.23.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arias E, Xu J. United States life tables, 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2022;71(1):1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascale M, Azinwi CN, Marongiu B, Pesce G, Stoffel F, Roggero E. The outcome of prostate cancer patients treated with curative intent strongly depends on survival after metastatic progression. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):651. 10.1186/s12885-017-3617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Røder MA, Brasso K, Berg KD, Thomsen FB, Gruschy L, Rusch E, et al. Patients undergoing radical prostatectomy have a better survival than the background population. Dan Med J. 2013;60(4):A4612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKay RR, Montgomery B, Xie W, Zhang Z, Bubley GJ, Lin DW, et al. Post prostatectomy outcomes of patients with high-risk prostate cancer treated with neoadjuvant androgen blockade. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(3):364–72. 10.1038/s41391-017-0009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freedland SJ, de Almeida LM, De Giorgi U, Gleave M, Gotto GT, Pieczonka CM, et al. Improved outcomes with enzalutamide in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(16):1453–65. 10.1056/NEJMoa2303974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):338–51. 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedland SJ, Allen J, Jarman A, Oyekunle T, Armstrong AJ, Moul JW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a 6-month low-carbohydrate intervention on disease progression in men with recurrent prostate cancer: Carbohydrate and Prostate Study 2 (CAPS2). Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(12):3035–43. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurwitz LM, Dogbe N, Hughes Barry K, Koutros S, Berndt SI. Obesity and prostate cancer screening, incidence, and mortality in the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023:djad113. 10.1093/jnci/djad113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Daniels JP, Freedland SJ, Gresham G. The growing implications of obesity for prostate cancer risk and mortality: where do we go from here? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023:djad140. 10.1093/jnci/djad140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinicaltrials/transparency. These data were made available by ConcertAI, Cambridge, MA, and used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Other researchers should contact ConcertAI, Real-World Data Products: https://www.concertai.com/data-products.