Abstract

Arginine modification can be a “switch” to regulate DNA transcription and a post-translational modification via methylation of a variety of cellular targets involved in signal transduction, gene transcription, DNA repair, and mRNA alterations. This consequently can turn downstream biological effectors “on” and “off”. Arginine methylation is catalyzed by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs 1–9) in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, and is thought to be involved in many disease processes. However, PRMTs have not been well-documented in the brain and their function as it relates to metabolism, circulation, functional learning and memory are understudied. In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview of PRMTs relevant to cellular stress, and future directions into PRMTs as therapeutic regulators in brain pathologies.

Keywords: Cellular stress, Protein arginine methyltransferases, Brain injury, Neuroinflammation, Transcription factors

1. Introduction

Arginine methylation is a post-translational modification that has implications in the DNA damage response, gene expression regulation, and mRNA translation (Guccione and Richard, 2019). More specifically, post-translational modifications are alterations on amino acid side chains that modify the protein’s structure, stability, and function (Zhong et al., 2020). These modifications in histone proteins have a notable role in defining chromatin structure and gene expression regulation. The most common types of post-translational modifications are acetylation/methylation of lysine/arginine residues (Carr et al., 2015). Methylation of lysine in histones, via protein lysine methyltransferase (PKMTs), and arginine residues, by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs,) are crucial to determine gene expression since methylation can lead to more condensed chromatin, which can prevent the access of transcription factors to their binding site (Hublitz et al., 2009; Jambhekar et al., 2019). While lysine methylation has a primary action of gene repression, arginine methylation can either activate or repress transcription. Although some of the PRMTs can be considered histone-specific, several PRMTs have been found to modify non-histone substrates (Yang and Bedford, 2013; Hamamoto et al., 2015). Methylation of non-histone proteins appears to be an indispensable post-translational modification, with a wide-range of roles in various cellular processes, including cell signaling, embryo development, cell cycle regulation, proliferation, survival, and differentiation (Carr et al., 2015; Hwang et al., 2021; Di Blasi et al., 2021). However, methylation of non-histone proteins is also implicated in cell stress response (Shi and Gibson, 2007), behavior (Godini et al., 2021), function (den Hoed et al., 2021), and cognitive disorders (Zhang et al., 2007).

PRMTs are a family of enzymes responsible for methylation of arginine residues in mammals (Bedford and Clarke, 2009). This methylation occurs by transferring methyl groups from S-adenosyl-L-methionine to target proteins, leading to changes in their stability, activity and localization (Angelopoulou et al., 2023). Humans have 9 PRMT isoforms, organized into 3 types depending on their methylation pattern. Type I PRMTs catalyze mono-methylation of the arginine residue forming mono-methyl arginine (MMA), and further methylating the same nitrogen atom again to form asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA). Type I PRMTs are composed by PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT3, PRMT4, PRMT6, and PRMT8, with PRMT1 being the most expressed one. Type II PRMTs catalyze mono-methylation of the arginine residue and further methylate the other nitrogen atom of the arginine residue to form both MMA and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA). Type II PRMTs are composed by PRMT5 and PRMT9. Type III PRMTs (PRMT7) only methylate one nitrogen atom forming MMA (Guccione and Richard, 2019; Morales et al., 2016).

PRMTs are highly expressed in the central nervous system and recent studies suggest their involvement in development, differentiation, and maturation of neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes (Angelopoulou et al., 2023). Therefore, PRMTs play an important role in neuronal function and development, often associated with neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s (AD), Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases, and other pathological scenarios including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, inflammation, and metabolic disorders (Angelopoulou et al., 2023; Jarrold and Davies, 2019; Couto et al., 2020; Srour et al., 2022; vanLieshout and Ljubicic, 2019). PRMT4 is overexpressed in 3xTg-AD mice to suggest compromised cerebral blood flow but restored upon PRMT4 inhibition (via TP-064) (Clemons et al., 2024). On the other hand, the accumulation of amyloid beta in AD can result in the inhibition of PRMT5 activity, leading to unregulated neuronal apoptosis (Angelopoulou et al., 2023). In this review, we aim to summarize the current knowledge of PRMTs, as modulators and response to neuronal stress evoked by various brain pathologies (i.e. AD, stroke) (Please see Table 1 and Fig. 1 for a summary of this review).

Table 1.

PRMTs and their relevant targets.

| PRMT | Switch | Target | Effect/Pathway | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PRMT1 | down | Nrf2 (R437) | Reduced protection against oxidative stress | Liu et al. (2016) |

| down | RelA (R30) | Increase expression of NF-κB target genes | Reintjes et al. (2016) | |

| up | p65 | Coactivate NF-κB-mediated transcription at the HIV-1 LTR promoter and MIP2 | Hassa et al. (2008) | |

| down | unknown | Increase accumulation of HIF-1α protein levels under hypoxic conditions | Lafleur et al. (2014) | |

| down | FOXO1 | Reduce stress-induced apoptosis | Yamagata et al. (2008) | |

| down | STAT1 (R31) | Reduce transcription of interferon-mediated anti-proliferative gene expression | Mowen et al. (2001) | |

| down | E2F1 | Reduce E2F1-dependent apoptosis | Zheng et al. (2013) | |

| down | unknown | Reduce dopaminergic neuronal cell death | Nho et al. (2020) | |

| down | MRE11 | S-phase checkpoint defects | Boisvert et al. (2005b) | |

| down | p53BP1/MRE11 | Decrease DNA repair capacity | Vadnais et al. (2018) | |

| down | FEN1 (R192) | Decrease cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy | He et al. (2020b) | |

| down | APE1 | Increase DNA damage in the mitochondria and sensitizes cells to oxidative stress | Zhang et al. (2020) | |

| down | CIITA | Activates MHC through IFN-y and CIITA enhanceassome | Fan et al. (2017) | |

| down | NIP45 | Impaired cytokine production by T helpers | Mowen et al. (2004) | |

| PRMT2 | up | unknown | Inhibit NF-κB-dependent gene expression and promotes cell death | Hassa et al. (2008) |

| down | BRD4 | Sensitizes cells to BET inhibitors and DNA damaging agents | Liu et al. (2022) | |

| up | unknown | Anti-depressant | Liu et al. (2024) | |

| up | Cobl | Induce neuronal morphogenesis | Hou et al. (2018) | |

| up | H3R8me2a | Co-activate oncogenic gene expression programs in Glioblastoma multiforme | Dong et al. (2018) | |

| PRMT3 | down | HIF1α | Inhibit angiogenesis in colorectal cancer | Zhang et al. (2021) |

| down | HIF1α | Repressed Glycolysis pathway | Zhou et al. (2024) | |

| PRMT4 | down | Histone 3 | Reduce arsenic-induced expression of ferritin gene | Huang et al. (2013) |

| down | unknown | Reduce NF-κB-mediated transcription at the HIV-1 LTR promoter | Hassa et al. (2008) | |

| down | p300 | Attenuate DNA damage response | Lee et al. (2011) | |

| down | Histone 3 | Decrease expression of NF-κB-dependent genes | Miao et al. (2006) | |

| PRMT5 | down | unknown | Reduce oxidative stress and inflammation-induced cell death | Diao et al. (2019) |

| down | p65 (R30) | Reduce expression of some NF-κB-regulated genes | Wei et al. (2013) | |

| down | unknown | Attenuate hypoxic induction of HIF-1α | Lim et al. (2012) | |

| down | FOXO1 | Disturb development of muscle and regeneration | Kim et al. (2023) | |

| down | Smad7 | Suppress cell proliferative activity | Cai et al. (2021) | |

| down | E2F1 | Retore regulatory activity of the cell cycle and Induce apoptosis in cancer cells | Sloan et al. (2023) | |

| down | H4 (R3) | Cell-cycle arrest (apoptosis and loss of cell migratory activity | Yan et al. (2014) | |

| down | 53BP1 | Reduce 53BP1 levels and impairs NHEJ DNA repair | Hwang et al. (2020) | |

| down | Rad9 | Increase susceptibility to DNA damage | He et al. (2011) | |

| down | RUVBL1 | Reduce DSB repair activity | Clarke et al. (2017) | |

| down | TDP1 | Increase cell replication, lethality and DNA damage | Rehman et al. (2018) | |

| down | KLF4 | Suppress tumor progression and Induce tumor cell death | Zhou et al. (2019) | |

| down | no enzymatic function | Potentiates RAIL-mediated cytotoxicity | Tanaka et al. (2009) | |

| down | p65 (R30) | Suggested therapy for rheumatoid arthritis | Chen et al. (2017) | |

| PRMT6 | down | H3R2 | Increase cellular senescence | Neault et al. (2012) |

| unknown | Polymerase beta | Enhance polymerase β DNA binding and processivity | El-Andaloussi et al. (2006) | |

| up | GPS2 | Increase expression of NF-κB target genes | Di Lorenzo et al. (2014) | |

| PRMT7 | down | unknown | Decrease hippocampal mitochondrial oxygen consumption rates | Acosta et al. (2023) |

| PRMT8 | down | unknown | Increase inflammatory response and reduce mitochondrial reserve capacity under hypoxia | Couto et al. (2021) |

| PRMT9 | down | SF3B2 | Increase alternative splicing, aberrant synapse development and impaired learning and memory | Shen et al. (2024) |

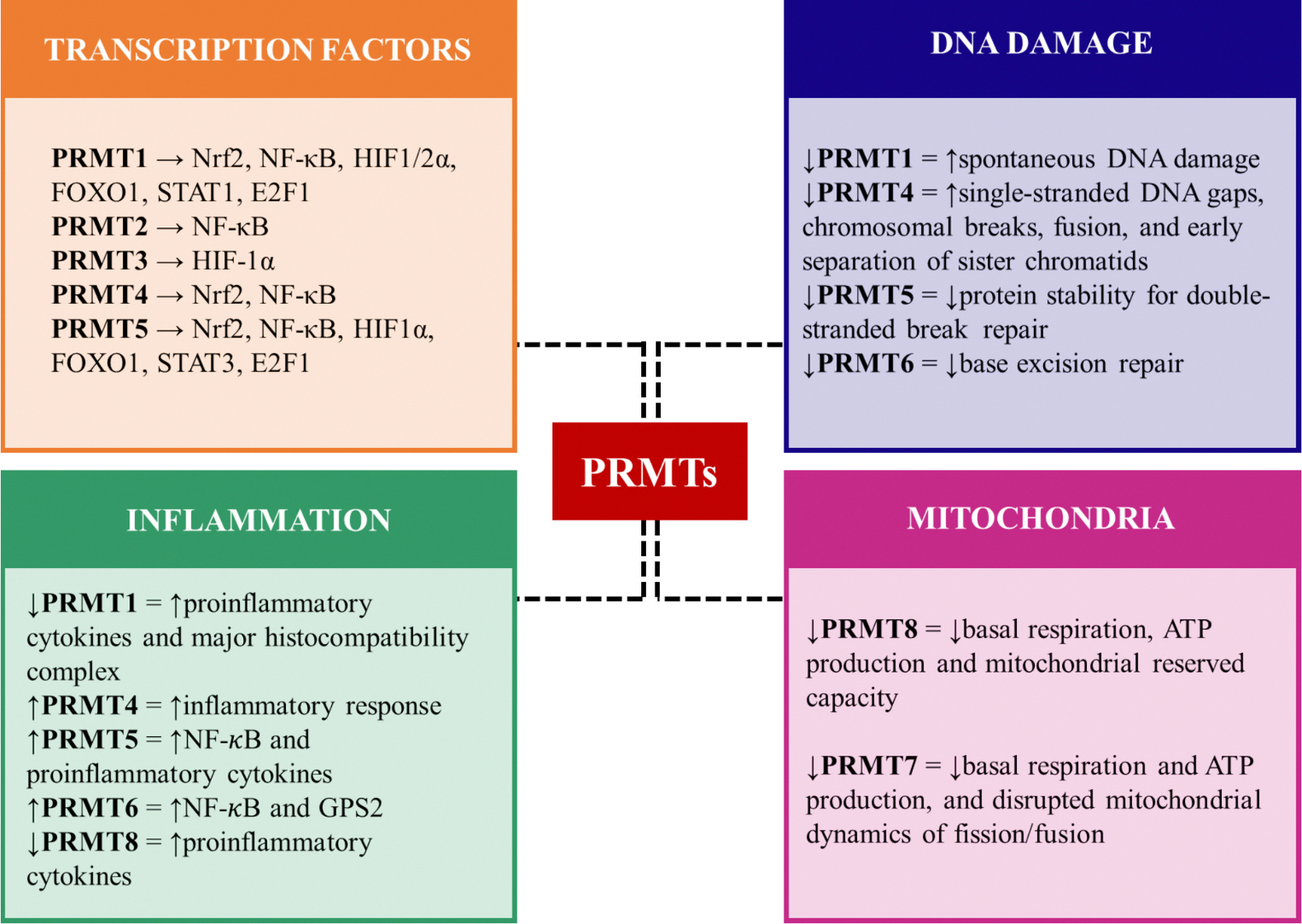

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing PRMT’s involvement in key cellular processes of stress response.

2. Transcription factors

Transcription factors also undergo post-translational modifications, which alter their DNA-binding activity and modulate protein-protein interactions, subcellular localization, transcriptional activity, and protein stability (Kim et al., 2021). Moreover, transcription factors can act as a DNA methylation reader, capable of recognizing methyl-lysine and methyl-arginine regions of the histone, therefore modulating gene expression (Zhu et al., 2016). PRMTs can regulate the activity of several transcription factors such as FOXO1 (Forkhead box protein O1), by PRMT1, which prevents proteasomal degradation and favors nuclear localization (Yamagata et al., 2008). Cell stress response in neurodegeneration comprises several key transcription factors, such as the nuclear factor (erythroid 2)–related factor 2 (Nrf2) (Suzen et al., 2022), the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) (Kaltschmidt et al., 2022), heat shock factors (HSFs) (Gomez-Pastor et al., 2018) and proteins (HSP) (Beretta and Shala, 2022), hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) (Correia et al., 2013), forkhead box O (FOXO) (Du and Zheng, 2021), CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) (Straccia et al., 2011), SRY-related HMG-box (SOX) (Stevanovic et al., 2023), homeobox (HOX) (Acquaah-Mensah et al., 2015), signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) (Wang et al., 2002), and E2F. All of these transcription factors are regulated through arginine methylation by PRMTs.

2.1. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)

Nrf2 is a transcription factor crucial for cellular defense against oxidative stress, as it activates cytoprotective gene expression (Gong and Yang, 2020; He et al., 2020a; Hammad et al., 2023) through binding of antioxidant response element (ARE), a regulatory sequence of DNA present in multiple genes of detoxification and antioxidant proteins (Chen and Kunsch, 2004). Nrf2 is the first transcription factor to bind to ARE and it was found that methylation by PRMT1 increased its’ transcriptional activity and DNA binding ability (Liu et al., 2016). Knocking down PRMT1 and PRMT4 blocks the binding of Nrf2 to the ARE of the ferritin gene in arsenic treated human cells interfering with cellular antioxidant response (Liu et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2013). Pyroptosis, a process of inflammation-induced cell death, via Nrf2/heme-oxygenase (HO-1) pathway is attenuated in ischemia/reperfusion model when PRMT5 is inhibited, all-the-while reducing oxidative stress. In confluence with the previous data, the protein levels of Nrf2 and HO-1 are also increased when PRMT5 is silenced (Diao et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022).

2.2. Nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB)

NF-κB is a family of inducible transcription factors that are involved in cellular stress, proliferation, synaptic plasticity, and learning/memory (Oeckinghaus and Ghosh, 2009; Snow and Albensi, 2016; Verma et al., 2023). RelA (p65) is one of the best-known NF-κB transcription factors relevant to AD. Expression and activation of p65 has been shown to up-regulate β-secretase cleavage and Aβ production, as observed in the brain of some sporadic AD patients (Snow and Albensi, 2016; Chen et al., 2012). One of the most prominent post-translational modifications of p65 is the methylation of arginine residues by PRMTs (Dai et al., 2022). Methylation of R30 (arginine 30) on p65, via PRMT5, occurs in response to interleukin IL-1b activation and it is essential for NF-κB-regulated genes that encode cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors (Wei et al., 2013). Reintjes et al. (2016) showed that PRMT1-mediated p65 methylation reduced overall expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Reintjes et al., 2016). Interestedly, Hassa et al. (2008) showed that NF-κB-dependent transcription at the HIV-1 LTR (long terminal repeat) promoter in vitro is regulated by several PRMTs, where PRMT1, with PRMT4 as co-activator, strongly activated p65, but PRMT2 and PRMT5 function as repressors of NF-κB (Hassa et al., 2008). Thus, the regulation of NF-κB activity through arginine methylation is extremely complex and context-dependent.

2.3. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs)

HIF is a transcription factor that triggers a cell survival program in conditions of oxygen deprivation, activating over 100 genes that encompass various cellular processes involved with hypoxia adaptation, such as anemia, tissue ischemia, angiogenesis, energy metabolism, cell proliferation, cell cycle control among others (Bouthelier and Aragones, 2020; Mitroshina and Vedunova, 2024). HIFs are heterodimeric transcription factors that have three isoforms of the α subunit (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α). HIF-1α and HIF-2α are critical for the hypoxia response (Kenneth and Rocha, 2008), but HIF-1α is neuroprotective, thus regulating gene expression associated with cell death during neurodegeneration (Iyalomhe et al., 2017). HIF-1 is controlled by multiple post-translational modifications on different amino acid residues of its subunits. The asymmetric methylation of R282 (of HIF1a) by PRMT3 increases HIF-1α stability, which favors gene expression related to angiogenesis and the HIF1/VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A) pathway, improving tissue vascularization (Zhang et al., 2021). Moreover, in a study with vascular calcification, the authors observed that depletion of PRMT3 regulated the glycolysis pathway by repressing the expression of β-glycerophosphate, Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) through HIF-1α (Zhou et al., 2024). In addition, PRMT1 can act as a repressor of HIF1/2α subunit; on the other hand, PRMT5 knockdown attenuated the hypoxic induction of HIF-1α, and the transcript levels of HIF-1-governed genes (i.e. VEGF, lysyl oxidase, and Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1), suggesting that PRMT5 is required for the HIF-1 signaling pathway (Lim et al., 2012; Lafleur et al., 2014).

2.4. Forkhead box protein (FOXO)

FOXO (part of the Forkhead family of transcription factors) protein target genes that encode metabolism and/or stress resistance mechanisms when cells are not generating enough energy or in the absence of insulin or insulin-like growth factors (Nemoto and Finkel, 2002; Oli et al., 2021). Several studies have suggested the potential involvement of FOXO in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s disease, amyloid lateral sclerosis, dementia and others (Maiese, 2016; Orea-Soufi et al., 2022). In AD patients FOXO3 is considered the largest inducer of cell death in response to Aβ mediated oxidative stress (Maiese, 2016). In fact, arginine methylation is one of the several post-translational modifications that regulate FOXO. PRMT1 can methylate the R248 and R250 residues within the FOXO motif blocking Akt (kinase protein)-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO1, changing the transcription factor’s activity. Reduced PRMT1 enhanced nuclear exclusion and proteasomal degradation of FOXO1 and decreased oxidative stress-induced apoptosis dependent of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway in HEK293 (Human Embryonic Kidney) cells, to suggest that FOXO1 methylation by PRMT1 activated expression of Bim gene (Bcl-2-interacting mediator), therefore, promotes apoptosis. Moreover, the knockdown of PRMT1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) proteins which regulate vascular endothelial growth factor, to promote vascular homeostasis (Yamagata et al., 2008). PRMT5 is another methyltransferase enzyme that regulates FOXO1’s activity. In a PRMT5 knockout mouse embryonic myoblasts, Kim et al., 2023 showed that FOXO1 levels were increased and accumulated in the cytosol of the myoblasts leading to activation of autophagy and depletion of lipid droplets resulting in disturbed development of muscle and regeneration (Kim et al., 2023).

2.5. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT)

The STAT family comprises a group of cytoplasmic transcription factors that modulate cellular responses to a diverse array of extracellular signals, including cytokines and growth factors. STAT protein activation is primarily driven by tyrosine phosphorylation, predominantly mediated by Janus kinases (JAKs) (Awasthi et al., 2021). The JAK/STAT signaling pathway is a pivotal mechanism in determining gliogenic cell fate, influenced significantly by the overactivation of microglia and astrocytes. This pathway plays a crucial role in neuroinflammation observed in neurodegenerative diseases, by initiating innate immune responses, coordinating adaptive immune mechanisms, and regulating neuroinflammatory responses (Rusek et al., 2023). In tauopathies, tau accumulation activates STAT1, which results in the suppression of synaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) transcription. Acetylated STAT1 forms complexes with STAT3 in the cytoplasm, inhibiting its nuclear translocation and activation. This inhibition directly suppresses NMDAR expression, contributing to synaptic dysfunction and memory impairment (Hong et al., 2020). Mowen et al. (2001) showed that PRMT1 methylate R31 on STAT1, regulating the transcription of interferon-mediated anti-proliferative gene expression (Mowen et al., 2001). Also, PRMT5 can directly methylate SMAD7 (Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7); such protein modification ensures robust STAT3 activation via the Smad7-STAT3 axis, which is necessary for cell proliferation, while PRMT5 silencing or inhibition results in suppression of cell proliferation (Cai et al., 2021).

2.6. E2F

The E2F family comprises of nine transcription factors, all involved in cell cycle regulation during G1/S transition, and DNA synthesis; E2F1, E2F2, E2F3a are gene activators, while E2F3b, E2F4-8 are gene repressors (Chen et al., 2009). The role in promoting cell cycle progression or apoptosis will depend on the transcriptional activation of a subset of E2F target genes (Chu et al., 2007). In neurons, aberrant re-entry into the cell cycle is a pathological event that contributes to the progression and severity of neurodegenerative diseases. Although some studies have suggested that this phenomenon immediately leads to cell death and apoptosis (Frade and Ovejero-Benito, 2015), others have suggested a non-proliferative role of the cell-cycle proteins leading to cell senescence (Wu et al., 2024; Frank and Tsai, 2009; Nandakumar et al., 2021).

E2F1 plays contradictory roles, such as promote cell-cycle progression v. apoptosis (Cho et al., 2012). PRMT1 can methylate E2F1, induce apoptosis; while PRMT5-dependent methylation promoted cellular proliferation (Zheng et al., 2013). Inhibition of PRMT5 led to restored regulatory activity of the cell cycle through retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (p-RB)/E2F, and apoptosis (p53-dependent/p53-independent) (Sloan et al., 2023). PRMT5 is overexpressed in glioblastoma cells (patient-derived primary tumors and cell lines), where genetic attenuation of PRMT5 expression led to cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and loss of glial cell migratory activity (Yan et al., 2014).

3. DNA damage response

The DNA damage response involves multiple proteins and pathways aimed to avoid genome mutation and consequently cell degeneration or cancer. There are at least five major pathways involved in DNA damage repair in mammalian cells (Huang and Zhou, 2021): mismatch repair (MMR), that resolves single nucleotide mismatches generated during replication (Li, 2008); base excision repair (BER), that corrects covalent additions to DNA bases (Caldecott, 2020); nucleotide excision repair (NER), that clears bulky adducts and cross-linking lesions (Yang and Bedford, 2013); homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), responsible for double-stranded breaks (Pannunzio et al., 2018). Posttranslational modifications are required for most of the DNA damage response proteins. PRMTs are essential in these processes, generating modified arginine residues such as mono-methylarginine (MMA), asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and/or symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA).

3.1. Type I PRMTs

PRMT1 is responsible for almost 90 % of all arginine methylation and is the most studied and described PRMT that methylate arginine residues (Dhar et al., 2013; Easton et al., 2000). It has been observed in models of Parkinson’s Disease that PRMT1 regulates dopaminergic neuronal cell death through DNA damage repair system involving PARP1 (Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1) – AIF (apoptosis-inducing factor) pathway. When SN4741 cells (a dopaminergic neuron model) are treated with 1-methyl-4-phenylpiridinium iodide (MPP+), which causes dopaminergic neuronal cell death, PRMT1 and histone 4R3 methylation is enhanced. Interestingly, MPP-induced dopaminergic neuronal cell death was reduced upon lower PRMT1 (via siRNA) levels to suggest that PRMT1 plays an important role in neuronal apoptotic pathways (Nho et al., 2020).

It is known that PRMT1 forms a complex with PARP1. Inhibition of PARP1 also reduced dopaminergic neuronal cell death provoked by MPP treatment while overexpression of PRMT1 leads to increased translocation of AIF to the nucleus, to suggest the importance of PRMT1 in apoptosis induced by DNA damage repair pathways via PARP1 and AIF (Nho et al., 2020). Although PARP1-AIF are not observed as being directly modified by PRMT1, many other proteins involved in the DNA damage response are substrates of PRMT1, such as MRE11 (Meiotic recombination 11), BRCA1 (Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein), 53BP1 (p53 binding protein 1), Pol β (polymerase beta), FEN1 (Flap endonuclease 1), APE1 (Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1), and hnRNPUL1 (Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein U Like 1).

MRE11 (Boisvert et al., 2005a; Boisvert et al., 2005b) is methylated by PRMT1 in the glycine arginine-rich (GAR) domain, which is required for exonuclease activity in the damaged DNA. MRE11 methylation interferes with the DNA damage checkpoint of the S-phase of the cell cycle (Boisvert et al., 2005a; Boisvert et al., 2005b). In mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), PRMT1 also methylates SAM68 (Src associated in mitosis, of 68 kDa), a protein involved in mRNA processing, transport, and translation (Bielli et al., 2011). PRMT1 is also essential for genome integrity and cell proliferation; loss of PRMT1 in MEFs leads to spontaneous DNA damage, delayed cell cycle progression, checkpoint defects, aneuploidy, and polyploidy. Additionally, the knockdown of PRMT1 in human osteosarcoma cells results in hypersensitivity to DNA damage along with a defect in the recruitment of the RAD51 (another protein involved in DNA damage repair) to the site of DNA damage (Yu et al., 2012). DNA damage repair proteins methylated by PRMT1 also affect 53BP1, playing a critical role in double-stranded break repair by promoting non-homologous end joining, while inhibiting homologous recombination (Yu et al., 2012; Vadnais et al., 2018). Furthermore, PRMT1 methylates DNA pol β and FEN1 at the arginine 137 and 192, respectively. This methylation interferes with the binding of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Guo et al., 2010). PRMT1 also methylates APE1 at arginine 301 (R301), which is enhanced by oxidative situations, such as H2O2 and menadione (Zhang et al., 2020). This methylation does not affect its nuclease activity but enhances APE1 binding to the mitochondrial outer membrane translocase (TOM20), promoting APE1 translocation to the mitochondria. Deficiency in R301 methylation increases DNA damage in the mitochondria and sensitizes cells to oxidative stress (Zhang et al., 2020).

PRMT4 is essential in the DNA replication fork, as observed in MEF cells, which will use low-fidelity mechanisms of replication (i.e.: allow errors) of the DNA even under stress when the methyltransferase is silenced (via siRNA). The knockdown of PRMT4 leads to more single-stranded DNA gaps, while increased chromosomal breaks, fusion, and early separation of sister chromatids in mitotic cells. The results of co-immunoprecipitation studies suggest that PRMT4 binds to PARP1 to slow down the DNA replication fork (Genois et al., 2021).

PRMT6 also plays a role in DNA damage response by modifying histones H3R2, H3R17, H3R42, and H2AR29 either producing MMA or ADMA (Casadio et al., 2013; Waldmann et al., 2011; Guccione et al., 2007; Hyllus et al., 2007). PRMT6 methylation of H3R2 leads to the repression of tumor suppressor expression, such as p53 and p21 (Guccione et al., 2007; Neault et al., 2012). However, a H3R42me2a modification by PRMT6 stimulates the transcription of genes controlled by p53 (Casadio et al., 2013). In addition, PRMT6 methylates Polymerase β, to enhance its binding to DNA, processivity of polymerase and base excision repair activity (BER) (El-Andaloussi et al., 2006).

3.2. Type II PRMTs

PRMT5 methylates the GAR motif of 53BP1, to increase protein stability, which is essential for double-stranded break repair. The SDMA modification in 53BP1 by PRMT5 competes with the ADMA catalyzed by PRMT1 (Hwang et al., 2020). PRMT5 also symmetrically dimethylates four arginine residues (R19, R100, R104, and R192) of FEN1, which drives the base excision repair pathway (LP-BER). Cells expressing the methylation deficient FEN1 mutant (R192K or 4RK) display higher levels of γH2AX (a phosphorylated histone indicative of unrepaired DNA accumulation) compared to cells expressing FEN1 wild-type, which make these mutant cells more sensitive to oxidative stresses (Guo et al., 2010).

RAD9 is a component of the 9-1-1 complex involved in the DNA damage response and is methylated by PRMT5, a modification essential for the activation of checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) signaling, which regulates the S/M and G2/M cell cycle checkpoints (He et al., 2011; Lieberman et al., 2017). RUVBL1 (RuvB Like AAA ATPase 1) is an AAA+ ATPase involved in chromatin remodeling, transcription, and DNA repair. RUBVL1 was identified as a PRMT5 interacting partner and substrate symmetrically dimethylated on R205 (Clarke et al., 2017). Depletion of RUBVL1 impaired homologous recombinant-mediated double-stranded repair leading to increased γH2AX upon ionizing radiation exposure (Clarke et al., 2017). PRMT5 also methylates TDP1 (Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1) at two arginine residues, and promotes TDP1 catalytic activity. TDP1 is an important DNA repair enzyme for the removal of trapped Top I (topoisomerase 1) cleavage complexes (TopIcc) that are generated by either DNA lesions (mismatches, abasic sites, nicks, and adducts) or Top I inhibitor (Camptothecin, CPT) during Top I-mediated cleavage–religation process. TopIcc may stall the progression of replication and transcription forks and generate DSBs. PRMT5 knock down leads to increased DNA damage in cells treated with CPT which implies that SDMA modification protects cells against DNA damage (Rehman et al., 2018).

4. Inflammation

Arginine methylation is an essential process of inflammatory regulation, mediated by the enzymatic actions of PRMT1, PRMT4, PRMT5, and PRMT6. These PRMTs act as inflammatory mediators by interacting with NF-κB (Srour et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2016). PRMT1’s methylation of NF-κB affects TNFα’s action in the inflammatory response. TNF-α is one of the primary proinflammatory cytokines that mediate systemic inflammation by stimulating the transcription of several genes involved in inflammation via NF-κB activation (i.e. A20, BCL-2, NLRP3, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, IL-1β, and IL-6) (Reintjes et al., 2016; Brasier, 2010; Liu et al., 2017). PRMT1 methylates the R30 site of the RelA/p65 subunit, prevent binding with the target DNA, and ultimately suppress gene expression responsive to TNF-α. PRMT1 acts as a negative regulator of inflammation through methylation of NF-κB. knockdown of PRMT1 also restores NF-κB targeted gene expression (NFKBIA, TNFα, and A20) in response to TNF-α (Reintjes et al., 2016).

Furthermore, PRMT1 has a role in the activation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC), it methylates CIITA (class II trans activator) leading to its degradation. CIITA associates with the DNA binding protein complexes to form the CIITA enhanceosome complex on the promoter of MHC class II genes to transactivate MHC class II genes. It is known that IFN-γ induce the expression of CIITA, and interestingly, downregulation of PRMT1 was observed in macrophage cells treated with IFN-γ. These findings suggest that PRMT1 reduce activation of MHC genes, which can reduce inflammatory response (Masternak et al., 2000; Meissner et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2017).

Likewise, PRMT1 is crucial for T helper’s cytokine production in an IL-4 and IFN-γ transcription activation manner. This process occurs by the arginine methylation of the N-terminal domain of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)-interacting protein (NIP45) which act as a co-activator of NFAT and induce expression of IL-4 and IFN-y genes (Mowen et al., 2004).

PRMT4’s role in the inflammatory response is still not fully understood. PRMT4 can regulate ICAM-1 (Intercellular adhesion molecule-1), G-CSF (Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor), MCP-1 (Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), and IP-10 (Interferon gamma-induced protein 10). The precise mechanism is unclear; however, a study by Miao et al. (2006) suggest that it is a co-activator through direct interaction with RelA/p65 in the presence of TNF-α (Miao et al., 2006). PRMT4 also methylates H3R17 histone in promoters involved in the inflammatory response, including TNF-α and IL-8 in monocytes (Miao et al., 2006). PRMT5 acts in the canonical NF-κB pathway, by binding with DR4 (Death receptor 4) protein and activating TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor, leading to multi-subunit IκB kinase (IKK) complex and NF-κB activation as well as triggering NF-κB target genes expression (Kim et al., 2016; Tanaka et al., 2020). Decreased PRMT5 activity causes an increase in TRAIL cytotoxicity, however without interfering with NF-κB signaling mediated by TNF-α action (Srour et al., 2022). PRMT5 also methylates the p65 subunit of NF-κB, regulating gene expression of several cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors NF-κB-dependent, such as IL-1α, IL-8, and TNF receptor-associated factor 1 (TRAF1). This methylation occurs at R30 and R35 with the methylation of R30 responsible for 85 % of NF-κB-dependent gene expression (Wei et al., 2013). Other studies suggest that PRMT5’s regulatory role on NF-κB pathways is caused by the IKK complex; inhibition of PRMT5 methylation led to reduced IKKβ and IKKα activation and RelA/p65 nuclear translocation. Lack of PRMT5 is also correlated with lower production of IL-6 and IL-8, as well as with inactivation of NF-κB, leading to cell proliferation and migration arrest (Chen et al., 2017).

PRMT6’s role in the regulation of inflammation is through direct interaction with NF-κB and G-protein pathway suppressor 2 (GPS2) (Di Lorenzo et al., 2014). A study with transgenic mice that overexpress PRMT6 showed that there is direct binding between PRMT6 and NF-κB (RelA/p65 subunit) that leads to increased expression of several NF-κB target genes, including IL-6, a process stimulated by TNF-α (Di Lorenzo et al., 2014). PRMT6 can have an indirect regulation of NF-κB through the methylation of coactivators, like p160/steroid receptor coactivator (SRC) proteins (Harrison et al., 2010). In addition to NF-κB methylation, PRMT6 also interacts with GPS2, a protein with several biological functions, including the mediation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), RAS protein and JAK signaling pathways, all essential for the inflammatory response (Kim et al., 2016). PRMT6’s action on GPS2 occurs by the methylation of R323 and R312, a necessary process that prevents degradation and ensures GPS2 stability. Thus, PRMT6 can act as a regulator of inflammation (Huang et al., 2015). Other inflammatory markers/modulators also include PRMT8. PRMT8 knockout mouse model had higher levels of TNF-α and IbaI protein as compared to wildtype mice, while overexpression of PRMT8 significantly reduced levels of both Iba1 and TNF-α (Couto et al., 2021). IbaI is an intracellular calcium-binding protein specific to microglia and macrophages, and an important inflammatory marker for several diseases, such as traumatic brain injury, epilepsy and AD (Ohsawa et al., 2004; Novoa et al., 2022). In addition, after hypoxia, PRMT8−/− mice had a significant reduction in rolling leukocyte speed as compared with WT mice, which suggests increased inflammatory response due to leukocyte extravasation into the brain. These findings suggest that PRMT8 may also be involved in neuroinflammation (Couto et al., 2021).

5. Mitochondria

Mitochondria is an organelle present in all cells and has the essential role of generating ATP, the source of energy involved in cellular metabolism. This organelle, sometimes referred to as the lung of the cell, due to oxygen consumption, is also involved in the regulation of cell apoptotic pathways and has been shown to play important role in the pathogenesis of AD (Bhatia et al., 2022; McBride et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2008; Trimmer et al., 2000).

Evidence of PRMTs, more specifically PRMT8’s role in the homeostasis of mitochondria was observed in knockout mice (PRMT8−/−), when oxygen consumption rate of the hippocampus decreases. Mice lacking in PRMT8 had reduced hippocampal basal respiration and ATP production compared to wild-type mice and its mitochondrial reserved capacity was significantly lower under hypoxia when compared to wild-type mice under hypoxia. Oxygen consumption rates were similar to wild type mice when mice lacking PRMT8 were injected with a virus to overexpress PRMT8 (Couto et al., 2021). Finally, importance of PRMT8 in the mitochondria activity was suggested by increased RNA expression of the reactive oxygen species markers transthyretin (TTR) and solute carrier family 3 member 1 (Slc3a1) in knockout mice (PRMT8−/−), as well as a significant increase in phosphatidic acid, a regulator of mitochondrial function (Couto et al., 2021; Kameoka et al., 2018).

PRMT7 can also modulate the mitochondria. In a mouse model of mild traumatic brain injury (rm-TBI), PRMT7 protein levels were significantly lower 3 days after the TBI hits and hippocampal mitochondrial oxygen consumption rates (via Seahorse XFe24), especially ATP production, were altered when compared to sham mice, along with disrupted mitochondrial dynamics of fission and fusion proteins. When PRMT7 was overexpressed (via AAV) in the rmTBI mice, mitochondrial reserve capacity was significantly increased and ATP levels were similar to sham mice levels (Acosta et al., 2023). Altogether, the data suggest that PRMT7 and PRMT8 can modulate mitochondria respiration and cell viability, important in responding to cellular stress and a wide-variety of pathologies.

6. Future direction

It is important to consider various PRMT isoforms (PRMT1-9) in different situations of AD, brain injury, and/or other cellular stress pathologies. Modulation of various PRMT isoforms can be of therapeutic importance. Identifying specific pathologies v. PRMTs involved is currently the challenge.

Since PRMT5 is frequently upregulated in many types of cancers, much research has focused on finding modulators of this type II PRMT. In fact, different PRMT5 inhibitors have undergone clinical trials, such as GSK3326595, JNJ-64619178, PF-06939999, PRT811, AMG 193, which so far have inconclusive data or limited clinical efficacy with some adverse effect (Pfizer, n.d.; GlaxoSmithKline, n.d.; Therapeutics, n.d.; Janssen Research and Development L, n.d.; Amgen, n.d.). There is an additional ongoing clinical trial (phase I/II) for safety and tolerability in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors with MTAP (methylthioadenosine phosphorylase) deletion with a selective PRMT5 inhibitor (TNG908), which is estimated to be completed by September of 2025 (Tango Therapeutics I, n.d.).

PRMT4 inhibitors, such as TP-064 (Nakayama et al., 2018) and EZM302 (Drew et al., 2017), were developed and pre-clinically tested for multiple myeloma, where upregulation of PRMT4 was observed. Interestingly, in old female AD-mice model that have PRMT4 protein levels higher in the brain, treatment with TP-064 lead to improvement of brain blood flow (Clemons et al., 2024). So far, no clinical trials targeting PRMT4 are in progress.

Although PRMT1 is the most studied PRMT, the only 2 clinical trials so far were not specific, targeting instead, overall type 1. The inhibitors comprise of GSK3368715 (GlaxoSmithKline, n.d.), discontinued in 2022 due to high rate of thromboembolic events, and CST2190 (CytosinLab Therapeutics Co. L, n.d.), which was recently initiated, both for the treatment of solid tumors. There are a number of other inhibitors of PRMTs (Couto et al., 2020; Tong et al., 2024) with some isoform-specific and some type I, II and III specific. Additional challenges include the lack of agonists that can be PRMT isoform-specific to be able to modulate PRMT activity when it is downregulated in pathology. Considering the low success of clinical trials, more investigations need to be performed regarding these intriguing family of enzymes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grants 1R01AG081258-01A1 (HWL), 1RF1NS132291-01 (HWL), 1R01AG081874-01 (HWL), and American Heart Association grants 22TPA970253 (HWL), and 24POST1196128 (MU).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Hung Wen Lin reports financial support was provided by National Institute of Health. Mariana Sayuri Berto Udo reports financial support was provided by American Heart Association. Hung Wen Lin reports financial support was provided by American Heart Association. Hung Wen Lin is the honorary treasurer of the International Society for the Study if Fatty Acids and Lipids (ISSFAL) If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Julia Zaccarelli-Magalhães: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Cristiane Teresinha Citadin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Julia Langman: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Drew James Smith: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Luiz Henrique Matuguma: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Hung Wen Lin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Mariana Sayuri Berto Udo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Acosta CH, Clemons GA, Citadin CT, et al. , 2023. PRMT7 can prevent neurovascular uncoupling, blood-brain barrier permeability, and mitochondrial dysfunction in repetitive and mild traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 366, 114445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acquaah-Mensah GK, Agu N, Khan T, Gardner A, 2015. A regulatory role for the insulin- and BDNF-linked RORA in the hippocampus: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 44, 827–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amgen. n.d. A Study of AMG 193 in Subjects With Advanced MTAP-null Solid Tumors (MTAP). ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT05094336. [Google Scholar]

- Angelopoulou E, Pyrgelis ES, Ahire C, Suman P, Mishra A, Piperi C, 2023. Functional implications of protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) in neurodegenerative diseases. Biology (Basel) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi N, Liongue C, Ward AC, 2021. STAT proteins: a kaleidoscope of canonical and non-canonical functions in immunity and cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford MT, Clarke SG, 2009. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol. Cell 33, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta G, Shala AL, 2022. Impact of heat shock proteins in neurodegeneration: possible Therapeutical targets. Ann. Neurosci. 29, 71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, Rawal R, Sharma P, Singh T, Singh M, Singh V, 2022. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: opportunities for drug development. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 20, 675–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielli P, Busa R, Paronetto MP, Sette C, 2011. The RNA-binding protein Sam68 is a multifunctional player in human cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18, R91–R102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, Hendzel MJ, Masson JY, Richard S, 2005a. Methylation of MRE11 regulates its nuclear compartmentalization. Cell Cycle 4, 981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, Dery U, Masson JY, Richard S, 2005b. Arginine methylation of MRE11 by PRMT1 is required for DNA damage checkpoint control. Genes Dev. 19, 671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthelier A, Aragones J, 2020. Role of the HIF oxygen sensing pathway in cell defense and proliferation through the control of amino acid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 1867, 118733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasier AR, 2010. The nuclear factor-kappaB-interleukin-6 signalling pathway mediating vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 86, 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Gu S, Yu Y, et al. , 2021. PRMT5 enables robust STAT3 activation via arginine symmetric Dimethylation of SMAD7. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 8, 2003047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldecott KW, 2020. Mammalian DNA base excision repair: dancing in the moonlight. DNA Repair (Amst) 93, 102921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr SM, Poppy Roworth A, Chan C, La Thangue NB, 2015. Post-translational control of transcription factors: methylation ranks highly. FEBS J. 282, 4450–4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadio F, Lu X, Pollock SB, et al. , 2013. H3R42me2a is a histone modification with positive transcriptional effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14894–14899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Zhou W, Liu S, et al. , 2012. Increased NF-kappaB signalling up-regulates BACE1 expression and its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15, 77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Zeng S, Huang M, Xu H, Liang L, Yang X, 2017. Role of protein arginine methyltransferase 5 in inflammation and migration of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 21, 781–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G, 2009. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 785–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XL, Kunsch C, 2004. Induction of cytoprotective genes through Nrf2/antioxidant response element pathway: a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho EC, Zheng S, Munro S, et al. , 2012. Arginine methylation controls growth regulation by E2F-1. EMBO J. 31, 1785–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Plowey ED, Wang Y, Patel V, Jordan-Sciutto KL, 2007. Location, location, location: altered transcription factor trafficking in neurodegeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 66, 873–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke TL, Sanchez-Bailon MP, Chiang K, et al. , 2017. PRMT5-dependent methylation of the TIP60 coactivator RUVBL1 is a key regulator of homologous recombination. Mol. Cell 65 (900–916), e907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons GA, Silva ACE, Acosta CH, et al. , 2024. Protein arginine methyltransferase 4 modulates nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 239, e30858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia SC, Carvalho C, Cardoso S, et al. , 2013. Defective HIF signaling pathway and brain response to hypoxia in neurodegenerative diseases: not an “iffy” question! Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 6809–6822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto ESA, Wu CY, Citadin CT, et al. , 2020. Protein arginine methyltransferases in cardiovascular and neuronal function. Mol. Neurobiol. 57, 1716–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto ESA, Wu CY, Clemons GA, et al. , 2021. Protein arginine methyltransferase 8 modulates mitochondrial bioenergetics and neuroinflammation after hypoxic stress. J. Neurochem. 159, 742–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CytosinLab Therapeutics Co. L. n.d. CTS2190 Phase I/II Clinical Study in Patients. ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: CT06224387. [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Zhang J, Li S, et al. , 2022. Protein arginine methylation: an emerging modification in Cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 13, 865964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S, Vemulapalli V, Patananan AN, et al. , 2013. Loss of the major type I arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 causes substrate scavenging by other PRMTs. Sci. Rep. 3, 1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasi R, Blyuss O, Timms JF, Conole D, Ceroni F, Whitwell HJ, 2021. Non-histone protein methylation: biological significance and bioengineering potential. ACS Chem. Biol. 16, 238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo A, Yang Y, Macaluso M, Bedford MT, 2014. A gain-of-function mouse model identifies PRMT6 as a NF-kappaB coactivator. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 8297–8309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao C, Chen Z, Qiu T, et al. , 2019. Inhibition of PRMT5 attenuates oxidative stress-induced Pyroptosis via activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signal pathway in a mouse model of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2345658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Li Q, Yang C, et al. , 2018. PRMT2 links histone H3R8 asymmetric dimethylation to oncogenic activation and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 9, 4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew AE, Moradei O, Jacques SL, et al. , 2017. Identification of a CARM1 inhibitor with potent in vitro and in vivo activity in preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Sci. Rep. 7, 17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S, Zheng H, 2021. Role of FoxO transcription factors in aging and age-related metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Biosci. 11, 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton RL, Patankar MS, Lattanzio FA, et al. , 2000. Structural analysis of murine zona pellucida glycans. Evidence for the expression of core 2-type O-glycans and the Sd(a) antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7731–7742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Andaloussi N, Valovka T, Toueille M, et al. , 2006. Arginine methylation regulates DNA polymerase beta. Mol. Cell 22, 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Li J, Li P, et al. , 2017. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) represses MHC II transcription in macrophages by methylating CIITA. Sci. Rep. 7, 40531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frade JM, Ovejero-Benito MC, 2015. Neuronal cell cycle: the neuron itself and its circumstances. Cell Cycle 14, 712–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CL, Tsai LH, 2009. Alternative functions of core cell cycle regulators in neuronal migration, neuronal maturation, and synaptic plasticity. Neuron 62, 312–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genois MM, Gagne JP, Yasuhara T, et al. , 2021. CARM1 regulates replication fork speed and stress response by stimulating PARP1. Mol. Cell 81 (784–800), e788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GlaxoSmithKline. n.d. Study to Investigate the Safety and Clinical Activity of GSK3326595 and Other Agents to Treat Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) and Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT03614728. [Google Scholar]

- GlaxoSmithKline. n.d. First Time in Humans (FTIH) Study of GSK3368715 in Participants With Solid Tumors and Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT03666988. [Google Scholar]

- Godini R, Handley A, Pocock R, 2021. Transcription factors that control behavior-lessons from C. Elegans. Front. Neurosci. 15, 745376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pastor R, Burchfiel ET, Thiele DJ, 2018. Regulation of heat shock transcription factors and their roles in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 4–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Yang Y, 2020. Activation of Nrf2/AREs-mediated antioxidant signalling, and suppression of profibrotic TGF-beta1/Smad3 pathway: a promising therapeutic strategy for hepatic fibrosis - a review. Life Sci. 256, 117909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione E, Richard S, 2019. The regulation, functions and clinical relevance of arginine methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 642–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione E, Bassi C, Casadio F, et al. , 2007. Methylation of histone H3R2 by PRMT6 and H3K4 by an MLL complex are mutually exclusive. Nature 449, 933–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Zheng L, Xu H, et al. , 2010. Methylation of FEN1 suppresses nearby phosphorylation and facilitates PCNA binding. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 766–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto R, Saloura V, Nakamura Y, 2015. Critical roles of non-histone protein lysine methylation in human tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 110–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammad M, Raftari M, Cesario R, et al. , 2023. Roles of oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling in pathogenic and non-pathogenic cells: a possible general mechanism of resistance to therapy. Antioxidants (Basel) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ, Tang YH, Dowhan DH, 2010. Protein arginine methyltransferase 6 regulates multiple aspects of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 2201–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassa PO, Covic M, Bedford MT, Hottiger MO, 2008. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 coactivates NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression synergistically with CARM1 and PARP1. J. Mol. Biol. 377, 668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Ru X, Wen T, 2020a. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Hu Z, Sun Y, et al. , 2020b. PRMT1 is critical to FEN1 expression and drug resistance in lung cancer cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 95, 102953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Ma X, Yang X, Zhao Y, Qiu J, Hang H, 2011. A role for the arginine methylation of Rad9 in checkpoint control and cellular sensitivity to DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 4719–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hoed J, Devaraju K, Fisher SE, 2021. Molecular networks of the FOXP2 transcription factor in the brain. EMBO Rep. 22, e52803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong XY, Wan HL, Li T, et al. , 2020. STAT3 ameliorates cognitive deficits by positively regulating the expression of NMDARs in a mouse model of FTDP-17. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W, Nemitz S, Schopper S, Nielsen ML, Kessels MM, Qualmann B, 2018. Arginine methylation by PRMT2 controls the functions of the actin Nucleator Cobl. Dev. Cell 45 (262–275), e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BW, Ray PD, Iwasaki K, Tsuji Y, 2013. Transcriptional regulation of the human ferritin gene by coordinated regulation of Nrf2 and protein arginine methyltransferases PRMT1 and PRMT4. FASEB J. 27, 3763–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Cardamone MD, Johnson HE, et al. , 2015. Exchange factor TBL1 and arginine methyltransferase PRMT6 cooperate in protecting G protein pathway suppressor 2 (GPS2) from proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 19044–19054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Zhou PK, 2021. DNA damage repair: historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hublitz P, Albert M, Peters AH, 2009. Mechanisms of transcriptional repression by histone lysine methylation. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 335–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JW, Kim SN, Myung N, et al. , 2020. PRMT5 promotes DNA repair through methylation of 53BP1 and is regulated by Src-mediated phosphorylation. Commun. Biol. 3, 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JW, Cho Y, Bae GU, Kim SN, Kim YK, 2021. Protein arginine methyltransferases: promising targets for cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 788–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyllus D, Stein C, Schnabel K, et al. , 2007. PRMT6-mediated methylation of R2 in histone H3 antagonizes H3 K4 trimethylation. Genes Dev. 21, 3369–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyalomhe O, Swierczek S, Enwerem N, et al. , 2017. The role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in mild cognitive impairment. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 37, 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambhekar A, Dhall A, Shi Y, 2019. Roles and regulation of histone methylation in animal development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 625–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen Research & Development L. n.d. A Study of JNJ-64619178, an Inhibitor of PRMT5 in Participants With Advanced Solid Tumors, NHL, and Lower Risk MDS. ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT03573310. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrold J, Davies CC, 2019. PRMTs and arginine methylation: Cancer’s best-kept secret? Trends Mol. Med. 25, 993–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt B, Helweg LP, Greiner JFW, Kaltschmidt C, 2022. NF-kappaB in neurodegenerative diseases: recent evidence from human genetics. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15, 954541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameoka S, Adachi Y, Okamoto K, Iijima M, Sesaki H, 2018. Phosphatidic acid and Cardiolipin coordinate mitochondrial dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth NS, Rocha S, 2008. Regulation of gene expression by hypoxia. Biochem. J. 414, 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Jeong MG, Hwang ES, 2021. Post-translational modifications in transcription factors that determine T helper cell differentiation. Mol. Cell 44, 318–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Yoo BC, Yang WS, Kim E, Hong S, Cho JY, 2016. The role of protein arginine methyltransferases in inflammatory responses. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 4028353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Oprescu SN, Snyder MM, et al. , 2023. PRMT5 mediates FoxO1 methylation and subcellular localization to regulate lipophagy in myogenic progenitors. Cell Rep. 42, 113329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafleur VN, Richard S, Richard DE, 2014. Transcriptional repression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) by the protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT1. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 925–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Bedford MT, Stallcup MR, 2011. Regulated recruitment of tumor suppressor BRCA1 to the p21 gene by coactivator methylation. Genes Dev. 25, 176–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GM, 2008. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 18, 85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman HB, Panigrahi SK, Hopkins KM, Wang L, Broustas CG, 2017. p53 and RAD9, the DNA damage response, and regulation of transcription networks. Radiat. Res. 187, 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Choi YJ, Cho CH, Park JW, 2012. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 is an essential component of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 signaling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 418, 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Lin B, Yin S, et al. , 2022. Arginine methylation of BRD4 by PRMT2/4 governs transcription and DNA repair. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Zhang B, Guo H, et al. , 2024. The antidepressant effects of protein arginine methyltransferase 2 involve neuroinflammation. Neurochem. Int. 176, 105728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC, 2017. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2, 17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li H, Liu L, et al. , 2016. Methylation of arginine by PRMT1 regulates Nrf2 transcriptional activity during the antioxidative response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 2093–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiese K, 2016. Forkhead transcription factors: new considerations for alzheimer’s disease and dementia. J. Transl. Sci. 2, 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masternak K, Muhlethaler-Mottet A, Villard J, Zufferey M, Steimle V, Reith W, 2000. CIITA is a transcriptional coactivator that is recruited to MHC class II promoters by multiple synergistic interactions with an enhanceosome complex. Genes Dev. 14, 1156–1166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S, 2006. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr. Biol. 16, R551–R560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner TB, Li A, Kobayashi KS, 2012. NLRC5: a newly discovered MHC class I transactivator (CITA). Microbes Infect. 14, 477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao F, Li S, Chavez V, Lanting L, Natarajan R, 2006. Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase-1 enhances nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated gene transcription through methylation of histone H3 at arginine 17. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1562–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitroshina EV, Vedunova MV, 2024. The role of oxygen homeostasis and the HIF-1 factor in the development of neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales Y, Caceres T, May K, Hevel JM, 2016. Biochemistry and regulation of the protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 590, 138–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowen KA, Tang J, Zhu W, et al. , 2001. Arginine methylation of STAT1 modulates IFNalpha/beta-induced transcription. Cell 104, 731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowen KA, Schurter BT, Fathman JW, David M, Glimcher LH, 2004. Arginine methylation of NIP45 modulates cytokine gene expression in effector T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell 15, 559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Szewczyk MM, Dela Sena C, et al. , 2018. TP-064, a potent and selective small molecule inhibitor of PRMT4 for multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 9, 18480–18493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar S, Rozich E, Buttitta L, 2021. Cell cycle re-entry in the nervous system: from polyploidy to neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 698661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neault M, Mallette FA, Vogel G, Michaud-Levesque J, Richard S, 2012. Ablation of PRMT6 reveals a role as a negative transcriptional regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 9513–9521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto S, Finkel T, 2002. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science 295, 2450–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nho JH, Park MJ, Park HJ, et al. , 2020. Protein arginine methyltransferase-1 stimulates dopaminergic neuronal cell death in a Parkinson’s disease model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 530, 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa C, Salazar P, Cisternas P, et al. , 2022. Inflammation context in Alzheimer’s disease, a relationship intricate to define. Biol. Res. 55, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S, 2009. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa K, Imai Y, Sasaki Y, Kohsaka S, 2004. Microglia/macrophage-specific protein Iba1 binds to fimbrin and enhances its actin-bundling activity. J. Neurochem. 88, 844–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oli V, Gupta R, Kumar P, 2021. FOXO and related transcription factors binding elements in the regulation of neurodegenerative disorders. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 116, 102012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orea-Soufi A, Paik J, Braganca J, Donlon TA, Willcox BJ, Link W, 2022. FOXO transcription factors as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43, 1070–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannunzio NR, Watanabe G, Lieber MR, 2018. Nonhomologous DNA end-joining for repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 10512–10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer. n.d. A Dose Escalation Study Of PF-06939999 In Participants With Advanced Or Metastatic Solid Tumors. ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT03854227. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman I, Basu SM, Das SK, et al. , 2018. PRMT5-mediated arginine methylation of TDP1 for the repair of topoisomerase I covalent complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 5601–5617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reintjes A, Fuchs JE, Kremser L, et al. , 2016. Asymmetric arginine dimethylation of RelA provides a repressive mark to modulate TNFalpha/NF-kappaB response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4326–4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusek M, Smith J, El-Khatib K, Aikins K, Czuczwar SJ, Pluta R, 2023. The role of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: new potential treatment target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Ma X, Wang Y, et al. , 2024. Loss-of-function mutation in PRMT9 causes abnormal synapse development by dysregulation of RNA alternative splicing. Nat. Commun. 15, 2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Gibson GE, 2007. Oxidative stress and transcriptional regulation in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 21, 276–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan SL, Brown F, Long M, et al. , 2023. PRMT5 supports multiple oncogenic pathways in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 142, 887–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow WM, Albensi BC, 2016. Neuronal gene targets of NF-kappaB and their dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9, 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srour N, Khan S, Richard S, 2022. The influence of arginine methylation in immunity and inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 2939–2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic M, Lazic A, Schwirtlich M, Stanisavljevic Ninkovic D., 2023. The role of SOX transcription factors in ageing and age-related diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straccia M, Gresa-Arribas N, Dentesano G, et al. , 2011. Pro-inflammatory gene expression and neurotoxic effects of activated microglia are attenuated by absence of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzen S, Tucci P, Profumo E, Buttari B, Saso L, 2022. A pivotal role of Nrf2 in neurodegenerative disorders: a new way for therapeutic strategies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Hoshikawa Y, Oh-hara T, et al. , 2009. PRMT5, a novel TRAIL receptor-binding protein, inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis via nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 557–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Nagai Y, Okumura M, Greene MI, Kambayashi T, 2020. PRMT5 is required for T cell survival and proliferation by maintaining cytokine signaling. Front. Immunol. 11, 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tango Therapeutics I n.d. Safety and Tolerability of TNG908 in Patients With MTAP-deleted Solid Tumors. ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT05275478. [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutics P n.d. A Study of PRT811 in Participants With Advanced Solid Tumors, CNS Lymphoma and Gliomas. ClinicalTrialsgov identifier: NCT04089449. [Google Scholar]

- Tong C, Chang X, Qu F, et al. , 2024. Overview of the development of protein arginine methyltransferase modulators: achievements and future directions. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 267, 116212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmer PA, Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, et al. , 2000. Abnormal mitochondrial morphology in sporadic Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease cybrid cell lines. Exp. Neurol. 162, 37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadnais C, Chen R, Fraszczak J, et al. , 2018. GFI1 facilitates efficient DNA repair by regulating PRMT1 dependent methylation of MRE11 and 53BP1. Nat. Commun. 9, 1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanLieshout TL, Ljubicic V, 2019. The emergence of protein arginine methyltransferases in skeletal muscle and metabolic disease. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 317, E1070–E1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma Y, Sachdeva H, Kalra S, Kumar P, Singh G, 2023. Unveiling the complex role of nf-Kappab in alzheimer’s disease: insights into brain inflammation and potential therapeutic targets. Georgian Med. News; 133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann T, Izzo A, Kamieniarz K, et al. , 2011. Methylation of H2AR29 is a novel repressive PRMT6 target. Epigenetics Chromatin 4, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Schreiber RD, Campbell IL, 2002. STAT1 deficiency unexpectedly and markedly exacerbates the pathophysiological actions of IFN-alpha in the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16209–16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Fujioka H, Zhu X, 2008. Dynamin-like protein 1 reduction underlies mitochondrial morphology and distribution abnormalities in fibroblasts from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 470–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, et al. , 2009. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 29, 9090–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Wang B, Miyagi M, et al. , 2013. PRMT5 dimethylates R30 of the p65 subunit to activate NF-kappaB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13516–13521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Sun JK, Chow KH, 2024. Neuronal cell cycle reentry events in the aging brain are more prevalent in neurodegeneration and lead to cellular senescence. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K, Daitoku H, Takahashi Y, et al. , 2008. Arginine methylation of FOXO transcription factors inhibits their phosphorylation by Akt. Mol. Cell 32, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Alinari L, Lustberg ME, et al. , 2014. Genetic validation of the protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 as a candidate therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 74, 1752–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Bedford MT, 2013. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Vogel G, Coulombe Y, et al. , 2012. The MRE11 GAR motif regulates DNA double-strand break processing and ATR activation. Cell Res. 22, 305–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Zeldin DC, Blackshear PJ, 2007. Regulatory factor X4 variant 3: a transcription factor involved in brain development and disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 3515–3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Pan W, Zhang Y, et al. , 2022. Comprehensive overview of Nrf2-related epigenetic regulations involved in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Theranostics 12, 6626–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang K, Feng X, et al. , 2021. PRMT3 promotes tumorigenesis by methylating and stabilizing HIF1alpha in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 12, 1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Li L, et al. , 2020. Arginine methylation of APE1 promotes its mitochondrial translocation to protect cells from oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 158, 60–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Moehlenbrink J, Lu YC, et al. , 2013. Arginine methylation-dependent reader-writer interplay governs growth control by E2F-1. Mol. Cell 52, 37–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Q, Xiao X, Qiu Y, et al. , 2020. Protein posttranslational modifications in health and diseases: functions, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. MedComm 2023 (4), e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Zhang C, Peng H, et al. , 2024. PRMT3 methylates HIF-1alpha to enhance the vascular calcification induced by chronic kidney disease. Mol. Med. 30, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Feng Z, Hu D, et al. , 2019. A novel small-molecule antagonizes PRMT5-mediated KLF4 methylation for targeted therapy. EBioMedicine 44, 98–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wang G, Qian J, 2016. Transcription factors as readers and effectors of DNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 551–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.