Abstract

Thoracolumbar burst fracture treatment in neurologically intact patients is controversial with many classification systems to help guide management. Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity score (TLICS) provides a framework, but evidence is limited, and recommendations are primarily based on expert opinion. In this retrospective cohort study, data was reviewed for patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures at a Level-1 Trauma Center in New England from 2013 to 2018. Neurologically intact patients without subluxation/dislocation on supine computed tomography were included. Multimodal pain control and early mobilization were encouraged. Patients that failed to mobilize due to pain were treated with operative stabilization. Outcome measures include degree of kyphosis, visual analog scale pain scores, and neurological function. Thirty-one patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures with TLICS scores of 4 or 5 were identified, of which 21 were treated nonoperatively. Kyphosis at final follow-up was 26.4 degrees for the nonoperative cohort versus 13.5 degrees for the operative group (P < .001). Nonoperative patients tended towards shorter hospital lengths-of-stay (3.0 vs 7.1 days, P = .085) and lower final pain scores (2.0 vs 4.0, P = .147) compared to the operative group. Two patients (6%) developed radicular pain with mobilization, which resolved after surgical intervention. No patients experienced decline in neurologic function. A trial of mobilization for neurologically intact TLICS grade 4 and 5 thoracolumbar burst fractures is a safe and reasonable treatment option that resulted in successful nonoperative management of 21 out of 31 (68%) patients.

Keywords: nonoperative management, thoracolumbar burst fracture, TLICS

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The majority of spine fractures occur at the thoracolumbar level.[1] Of these, burst fractures account for 10% to 20%.[2] The neurologically intact patient with this injury pattern represents a challenging clinical scenario as there are multiple classification systems aimed at guiding treatment and opinions differ on optimal management.[2–11]

Operative and nonoperative strategies are both well supported in the literature.[12–15] The classification systems used to guide treatment of these injuries have been created on the basis of expert opinion, including the widely-used Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity score (TLICS) which is frequently employed to describe the degree of thoracolumbar trauma and guide management.[4,16] Notably, the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen spine thoracolumbar classification system represents a newer alternative system for describing these injuries, but the structural outline and data gathering for this review began prior to the widespread adoption of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen spine system.[17]

The TLICS score system assigns points (Table 1)[16] based on morphology of the injury, presence of neurological deficits, and competence of the posterior ligamentous complex. It also assigns a management category based on the number of points (Table 1).[16] According to this system, a burst fracture (2 points) with an indeterminate ligamentous injury (2 points) in a neurologically intact patient (0 points) would have a score of 4 and could be treated either operatively or nonoperatively at the surgeon’s discretion. A burst fracture (2 points) with clear ligamentous injury (3 points) in a neurologically intact patient (0 points) brings the score to 5 and should be treated operatively. The distinction between these 2 categories can be challenging to define with limited interrater reliability and is perhaps overly reified in the clinical decision-making process.[18]

Table 1.

TLICS guide and suggested management.

| Parameter | Points |

|---|---|

| Morphology | |

| Compression fracture | 1 |

| Burst fracture | 2 |

| Translational/rotational | 3 |

| Distraction | 4 |

| Neurological involvement | |

| Intact | 0 |

| Nerve root | 2 |

| Cord, conus medullaris | |

| Incomplete | 3 |

| Complete | 2 |

| Cauda equina | 3 |

| Posterior ligamentous complex | |

| Intact | 0 |

| Injury suspected/indeterminate | 2 |

| Injured | 3 |

| Management | Points |

| Nonoperative | 0–3 |

| Nonoperative or operative | 4 |

| Operative | ≥5 |

TLICS = Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity score.

1.2. Rationale

The purpose of this study was to test our hypothesis that neurologically intact patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures and a TLICS score of not only 4 but also 5 can be safely managed with a trial of nonoperative management. We are unaware of any previous such study. We present a clear protocol for pain control to optimize mobilization and provide a framework to trial nonoperative treatment and demonstrate no neurologic complications with early mobilization.

2. Materials and methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to initiating this retrospective review. Between January 2016 and November 2018 patients treated at a single Level-1 Trauma Center in the Northeast with fractures between T10 and L2 were prospectively identified and marked in the electronic medical record for later review. Patients were also retrospectively identified by a search of the hospital database for International Classification of Diseases-10 codes specific to these injuries for the period between April 2013 and December 2015 since these had not been marked in the electronic medical record upon initial presentation.

The records and radiographs of identified patients were subsequently analyzed. Inclusion criteria consisted of immediate presentation to an emergency department following acute injury, a diagnosis of thoracolumbar burst fracture between T10 and L2 (as these junctional vertebrae were the most frequently observed fractured levels at our institution and most characteristic for these injuries more broadly), TLICS score of 4 or 5, no motor or sensory deficits in the lower extremities, and ability to read and speak the English language.[4,19] Exclusion criteria comprised the following: any neurologic deficits, subluxation/dislocation or translation injuries, pathologic fractures, or incomplete data available for review (including immediate loss to follow-up after hospital discharge).

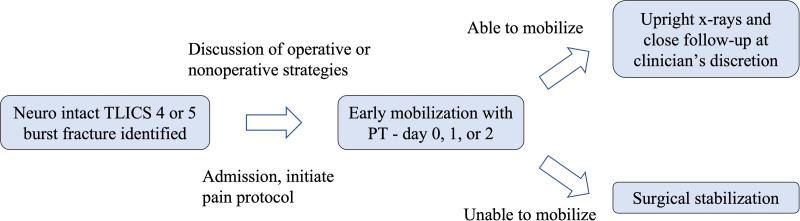

On admission to our facility supine computed tomography (CT) of the thoracolumbar spine was performed to evaluate fracture morphology. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were uniformly treated with multimodal pain control consisting of 1000 mg of scheduled acetaminophen, 500 mg scheduled methocarbamol, 50 mg tramadol as needed, and 5 to 15 mg oxycodone as needed (some patients also received as needed ketorolac and/or morphine per surgeon discretion as well as a titrated dose of gabapentin if radicular symptoms were present) (Fig. 1). Additionally, all patients in the retrospective cohort from 2013 to 2015 were prescribed a brace as an adjunct to nonoperative management. There was a departmental shift away from bracing in the time interval between the retrospective and prospective cohorts, so patients identified from 2016 to 2018 were treated without bracing. This shift reflected growing evidence of the potential risks of bracing (skin issues, discomfort) in addition to a lack of evidence of increased efficacy compared to non-bracing options.[20]

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting pathway for nonoperative management of neurologically intact thoracolumbar burst fractures.

Upright static AP and lateral radiographs centered at the level of the injury were obtained as soon as patients could tolerate them. Dynamic radiographs and magnetic resonance were not routinely obtained. Patients were also encouraged to mobilize with physical therapy. Those who were unable to mobilize after several attempts with a dedicated physical therapist or who failed to tolerate upright imaging due to the severity of their pain underwent operative intervention. Surgery consisted of posterior spinal fusion without decompression with pedicle screws and spanning rods either 1 or 2 levels above and below the site of the fracture. One patient additionally underwent corpectomy with humeral shaft allograft in order to directly reinforce the anterior column to assist in addressing global sagittal imbalance in the setting of focal kyphosis of 38 degrees. Postoperative upright AP and lateral radiographs were obtained prior to discharge from the hospital for all patients treated with surgery. Both nonoperative and operative patients were generally seen in clinic at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks post-injury, after which additional follow-up visits were scheduled at the discretion of the treating physician. In total, 16 operative patients were potentially eligible, of which 13 were confirmed eligible, and 10 completed follow-up and were analyzed in the study. For the nonoperative patients, 36 patients were potentially eligible, of which 4 were immediately lost to follow-up and complete data were available for 21, who were analyzed in the final study.

Fractures were classified using the TLICS score system.[4,16] Measured radiographic parameters included focal kyphosis at the fractured level, vertebral body height loss, canal compromise, and interspinous splaying. These were measured on either CT scan or supine lateral radiograph at the time of injury, followed by upright lateral radiographs at time of injury (or postoperatively) and at latest follow-up. The Cobb angle technique was used to measure kyphosis, which was defined as the angle formed from a line drawn parallel to the superior endplate of the vertebra 1 level above the fractured vertebra and a line drawn parallel to the inferior endplate of the vertebra 1 level below the fractured level.[21] Vertebral body height loss was measured as the ratio of the height of the most compressed section of the fractured vertebral body to the average height of the posterior vertebral bodies of the intact vertebrae above and below. Canal-compromise was measured on CT as the ratio of anterior-to-posterior diameter of the spinal canal at the level on axial CT scan with the most stenosis due to the retropulsed fracture fragment as compared to average canal diameter of the intact vertebrae above and below. To assess for posterior longitudinal complex instability, the distance between the facets of the fractured vertebra was compared to the average distance between those of the vertebrae adjacent to the injured level. Additionally, the interspinous distance between the fractured vertebra and those cranial and caudal to it were also compared to assess the stability of the posterior longitudinal complex.[22] Three attending spine surgeons (RM, DL, CZ) and 2 orthopedic residents (PS, SB) evaluated the available imaging until a consensus was obtained. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student t test to compare underlying patient demographics and outcomes between the operative and nonoperative groups (in addition to the differences between the subset of the nonoperative patient treated both with and without bracing). Institutional review board approval at the University of Vermont was obtained prior to initiating this retrospective review (CHRMS [Medical]: STUDY00000011). A waiver of consent was authorized under 46.116(f)(1)(3), 46.164.512(i)(1)(2).

3. Results

During the study period we encountered 52 patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures, of which 31 met inclusion criteria, had complete data, and completed follow-up, thus were included in our study group. There were 23 males and 8 females with an average age of 53.2 years (range of 15–82 years). The most common mechanisms of injury were falls from a height, followed by motor vehicle collision. Other mechanisms included all-terrain vehicle crash, snowmobile crash, sledding accident, fall from a horse, and avalanche. Pertinent patient demographics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient demographics and fracture characteristics.

| Characteristic | Operative | Nonoperative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 21 | |

| Age at injury (years) | 50.0 | 54.7 | |

| Length of follow-up (days) | 336 | 89 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 | 15 | |

| Female | 2 | 6 | |

| Level | |||

| T10 | 0 | 1 | |

| T11 | 0 | 0 | |

| T12 | 3 | 8 | |

| L1 | 5 | 10 | |

| L2 | 2 | 2 | |

| TLICS score | |||

| TLICS 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| TLICS 5 | 6 | 13 |

TLICS = Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity score.

The nonoperative group included 21 patients with 15 males and 6 females with an average age of 54.7 (range 26–82 years). Injured levels included T10 and T12 through L2. Height loss and canal compromise averaged 43% and 29%, respectively. Local kyphosis averaged 16.7 degrees supine and 22.3 degrees upright at presentation and 26.4 degrees at final follow-up. Length of hospital stay averaged 10.1 days with a range of 0 to 153 days (recalculated without an outlier—a patient whose disposition was complicated by unhoused status and lack of social support, this average was 3.0 days with a range of 0 to 28. This value is reflected in Table 2). The average duration for follow-up was 89 days with a range of 32 to 1550. Average visual analog scale (VAS) pain score at final follow-up was 2.0 (Table 3). No patients in the nonoperative group suffered a decline in motor function or new radiculopathy at discharge or at final follow-up clinic visit. The decision to utilize a brace was made at the discretion of the treating surgeon, with 16 of 21 patients being treated without one. With the exception of vertebral body height loss at presentation (47% non-braced vs 29% braced, P < .05), there were no differences in underlying characteristics or outcomes between the braced and non-braced groups (Table 4).

Table 3.

Results stratified by operative status with associated P-values.

| Results | Operative | Nonoperative | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital day of surgery | 2.7 | – | |

| Length of hospital stay (days)* | 7.1 | 3.0 | .085 |

| Initial supine kyphosis (degrees) | 15.1 | 16.7 | .684 |

| Initial upright kyphosis (degrees) | – | 22.3 | |

| Postoperative upright kyphosis (degrees) | 9.4 | – | |

| Final follow-up upright kyphosis (degrees) | 13.5 | 26.4 | .0009 |

| Initial height loss | 42% | 43% | .904 |

| Canal compromise | 45% | 29% | .061 |

| VAS at final follow-up | 4.0 | 2.0 | .147 |

VAS = visual analog scale.

Outlier removed.

Table 4.

Results for nonoperative patients stratified by bracing status with associated P-values.

| Results | Braced | Non-braced | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 5 | 16 | |

| Length of hospital stay (days)* | 2.5 | 3.1 | .877 |

| Initial supine kyphosis (degrees) | 11.2 | 18.5 | .175 |

| Initial upright kyphosis (degrees) | 17.4 | 23.9 | .159 |

| Final follow-up upright kyphosis (degrees) | 21.2 | 28.1 | .189 |

| Initial height loss | 29% | 47% | .022 |

| Canal compromise | 25% | 31% | .588 |

| VAS at final follow-up | 2.5 | 1.9 | .629 |

VAS = visual analog scale.

Outlier removed.

The operative group consisted of 10 patients (8 males, 2 females) with an average age of 50.0 years and range of 15–82 years. Each vertebral level from T12 through L2 was represented. Height loss and canal compromise averaged 42% and 45%, respectively. Local kyphosis averaged 15.1 degrees supine at presentation, 9.4 degrees on postoperative upright radiographs, and 13.5 degrees at final follow-up. Hospital day of surgery was 2.7 on average. Two of the 10 patients underwent surgery due to radicular pain symptoms with attempted mobilization. Seven proceeded to the operating room due to back pain (one of these due to persistent pain at outpatient follow-up). Finally, 1 patient was admitted with an immediate plan for surgical fixation, without trial of nonoperative management at the discretion of the treating surgeon. The total length of hospital stay averaged 7.1 days with a range of 2 to 21 days. The duration of follow-up averaged 336 days (range: 59–1635). Final VAS pain score averaged 4.0. Similarly to the nonoperative group, no patients in the operative group suffered declines in motor function or new radiculopathy through final follow-up clinic visits (Table 3).

3.1. Case examples

3.1.1. Nonoperative case

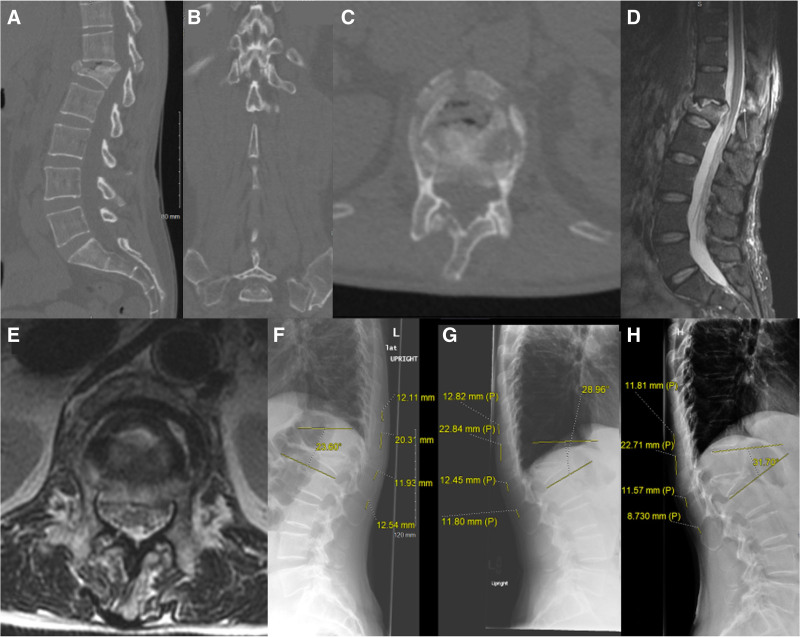

KC is a 57-year-old female who fell down a flight of stairs and sustained an L1 burst fracture. She was neurologically intact following the accident and presented to the emergency department. Imaging (Fig. 2) showed a TLICS 5 injury (burst morphology, posterior ligamentous complex injury, and neurologically intact). She was admitted for observation, pain control, and mobilization with physical therapy. She was discharged from the hospital 3 days later. Over the course of her follow-up she remained neurologically intact and pain gradually improved to the point that at final follow-up over 5 months after initial injury VAS pain score was 0. She returned to work at a desk job without restrictions.

Figure 2.

(A–H) Images A to C are selected parasagittal, coronal, and axial CT cuts demonstrating an L1 burst fracture with extension to the T12–L1 facet joints and T12 spinous process. Images D and E are selected parasagittal and axial MRI sequences revealing disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex with ligamentum flavum injury (white arrow). Image F is the initial upright lateral radiograph which shows the degree of kyphosis and interspinous distances at time of admission. Images G and H are upright radiographs taken at 6 weeks and 5 months respectively indicating slight progression of kyphosis and interspinous splaying.

3.1.2. Operative case

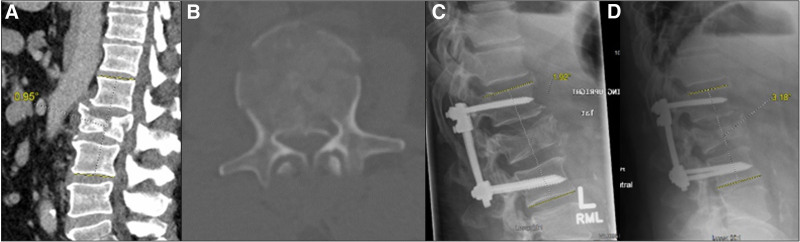

BR is a 57-year-old male who fell 20 feet from a ladder against a telephone pole and sustained an L2 burst fracture (Fig. 3). He had no motor or sensory deficits but did have radicular pain immediately after the accident. This pain had worsened in severity by the time he reached the emergency department and was refractory to neuroleptic medication. He was found to have a TLICS 4 fracture of L2 (burst morphology, indeterminate posterior ligamentous complex, and neurologically intact). Due to his worsening leg symptoms, he was taken to the operating room on hospital day 1 and underwent L1 to L3 posterior fusion with bone graft without decompression. He was discharged on postoperative day 5 with full strength in the bilateral lower extremities and with resolution of radiculopathy. By latest follow-up, his kyphosis had increased from 1.9 to 3.2 degrees, he had full strength in the lower extremities, his radiculopathy had not returned, and his pain was stable (VAS 2 on day of discharge and at latest follow-up.)

Figure 3.

(A–D) Images A and B show selected parasagittal and axial CT images demonstrating an L2 burst fracture with indeterminate posterior ligamentous complex injury. Images C and D are initial postop and final postop lateral radiographs, respectively.

4. Discussion

Since thoracolumbar fractures were first classified based on mechanism of injury and anatomic considerations, no fewer than ten classification schemes have been devised to aid clinicians in characterizing the degree of injury and help guide treatment.[2–11] Thoracolumbar burst fractures represent a complex injury pattern with both bony and ligamentous involvement, making classification challenging. Classification schema have continually evolved as new information has been introduced, such as the stability provided by the posterior ligamentous complex of the affected segments.[2] Despite the challenges associated with classification of these injuries, these systems are relied upon to aid in developing a clear treatment plan for each patient. Therefore, it is of pivotal importance to correctly identify which injury patterns can withstand physiologic loading and thus are potentially amenable to nonoperative treatment.

This study is the first case series to trial non operative management for patients with thoracolumbar burst fractures and a TLICS score of either 4 or 5. We demonstrate that these injuries can be satisfactorily managed without surgical intervention in the neurologically intact and therefore recommend that patients be offered a trial of nonoperative management at the time of presentation. This is in contrast to other published recommendations which support surgical stabilization for patients with scores of 5 within the TLICS framework.[4] Throughout the duration of our study, no patients (including those treated nonoperatively) developed any neurological deficits. Two patients out of 31 total (6.4%) developed worsening of radicular pain which was present on arrival. Both patients underwent surgical intervention with subsequent resolution of radicular symptoms, suggesting that surgery is a reasonable option for patients presenting with refractory radicular pain.

Overall, patients treated nonoperatively were found to tend towards shorter hospital stays and less pain at final follow-up. Comparing the operative and nonoperative groups, the only injury characteristic that differed significantly was final upright kyphosis (operative group: 13.5 degrees, nonoperative group 26.4 degrees P = .0009). None of these factors played a direct role in the decision-making process for determining treatment plan. There were no significant differences in underlying demographics (age, gender) or other fracture characteristics (level, TLICS score, initial supine kyphosis, and height loss) between the 2 groups.

Patients treated operatively exhibited less kyphosis on final upright imaging but there was no difference in neurologic function between the groups during the duration of their hospitalization and patients treated nonoperatively tended towards lower VAS pain scores at final follow-up (2.0 vs 4.0). Pain is a particularly challenging problem in the acutely injured spine patient. We believe that a very important aspect of successfully treating these injuries nonoperatively is early counseling and utilization of a multimodal pain control regimen coupled with early, aggressive physical therapy. These resources are available at any hospital that treats burst fractures, regardless of location. Concerning brace use in nonoperative patients, aside from initial vertebral body height loss, we found no significant differences in any other measured outcomes between the subset of nonoperative patients treated with bracing versus without it. No operative patients were prescribed a brace.

This study has several limitations. Due to the small number of patients, it is difficult to identify differences between fracture characteristics. However, this is mitigated by the fact that TLICS can be applied to all burst fractures and also considers ligamentous injury. Although specific fracture characteristics are not reported in this study, the generalizability of TLICS make it a useful tool for classification and management. While detailed fracture morphology description aids in understanding the degree of bony injury, such detail may not guide management principles. Additionally, northern New England contains a relatively homogenous patient population which may limit the generalizability of this work. A further limitation of our study is lack of follow-up data. Follow-up for the nonoperative patients averaged 89 days versus 336 for operative patients. This is largely a reflection of departmental practice patterns (with ~3 months follow-up for nonoperative fractures and ~12 months for operative fractures) in addition to the fact that follow-up beyond the 12-week mark was scheduled at the discretion of the treating surgeon. That said, the potential for lower duration of follow-up to fail to capture the true incidence of meaningful post-injury neurologic decline is mitigated by the fact that there is only 1 major health network within the region of the study.

This work builds upon the work of others who have demonstrated that patients with TLICS scores of 4 can be reasonably managed nonoperatively.[12] Our study extends this work to also include neurologically intact TLICS 5 injuries. Whereas at many institutions, patients with TLICS scores of 4 and 5 would be routinely treated surgically, we have demonstrated that over 67% of these patients were successfully treated without surgery, with satisfactory neurologic function, avoidance of peri-operative risk, and trends toward better pain scores and shorter lengths-of-stay. Though further investigation is needed to better refine our classification systems and management strategies for thoracolumbar burst fractures in the neurologically intact, our data suggest that these patients should be given a trial of nonoperative management.

5. Conclusion

A trial of mobilization for neurologically intact TLICS grade 4 and 5 thoracolumbar burst fractures is a safe and reasonable treatment option that resulted in successful nonoperative management of 21 out of 31 (68%) patients.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Peter Shorten, Benjamin Kagan, Robert Monsey.

Data curation: Peter Shorten, Benjamin Kagan, David Lunardini, Robert Monsey.

Formal analysis: Shawn Best, David Lunardini, Robert Monsey.

Investigation: Peter Shorten, Benjamin Kagan, Martin Krag, Robert Monsey.

Methodology: Peter Shorten, Martin Krag.

Project administration: Chason Ziino, Robert Monsey.

Supervision: Chason Ziino, David Lunardini, Robert Monsey.

Writing – original draft: Shawn Best.

Writing – review & editing: Shawn Best, Chason Ziino, David Lunardini, Martin Krag, Robert Monsey.

Abbreviations:

- CT

- computed tomography

- TLICS

- Thoracolumbar Injury Classification and Severity score

- VAS

- visual analog scale

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Institutional review board approval at the University of Vermont was obtained prior to initiating this retrospective review (CHRMS [Medical]: STUDY00000011). A waiver of consent was authorized under 46.116(f)(1)(3), 46.164.512(i)(1)(2).

How to cite this article: Best SA, Shorten PL, Ziino C, Kagan BD, Lunardini DJ, Krag MH, Monsey RD. The neurologically intact patient with TLICS 4 or 5 burst fracture should be given a trial of nonoperative management. Medicine 2024;103:46(e40304).

Contributor Information

Peter L. Shorten, Email: peter.shorten10@gmail.com.

Chason Ziino, Email: Chason.Ziino@uvmhealth.org.

Benjamin D. Kagan, Email: Benjamin.kagan@uvmhealth.org.

David J. Lunardini, Email: David.Lunardini@uvmhealth.org.

Martin H. Krag, Email: martin.krag@med.uvm.edu.

Robert D. Monsey, Email: Robert.Monsey@uvmhealth.org.

References

- [1].den Ouden LP, Smits AJ, Stadhouder A, Feller R, Deunk J, Bloemers FW. Epidemiology of spinal fractures in a level one trauma center in the Netherlands: a 10 years review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44:732–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:817–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Oner C, Rajasekaran S, Chapman JR, et al. Spine trauma-what are the current controversies? J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31(Suppl 4):S1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vaccaro AR, Zeiller SC, Hulbert RJ, et al. The thoracolumbar injury severity score: a proposed treatment algorithm. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:209–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nicoll EA. Fractures of the dorso-lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31B:376–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ferguson RL, Allen BL, Jr. A mechanistic classification of thoracolumbar spine fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984:77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Holdsworth F. Fractures, dislocations, and fracture-dislocations of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:1534–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kelly RP, Whitesides TE, Jr. Treatment of lumbodorsal fracture-dislocations. Ann Surg. 1968;167:705–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, Harms J, Nazarian S. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:184–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McAfee PC, Yuan HA, Fredrickson BE, Lubicky JP. The value of computed tomography in thoracolumbar fractures. An analysis of one hundred consecutive cases and a new classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:461–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McCormack T, Karaikovic E, Gaines RW. The load sharing classification of spine fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1741–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wood KB, Buttermann GR, Phukan R, et al. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of a thoracolumbar burst fracture without neurological deficit: a prospective randomized study with follow-up at sixteen to twenty-two years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Abudou M, Chen X, Kong X, Wu T. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD005079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seybold EA, Sweeney CA, Fredrickson BE, Warhold LG, Bernini PM. Functional outcome of low lumbar burst fractures. A multicenter review of operative and nonoperative treatment of L3–L5. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:2154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pehlivanoglu T, Akgul T, Bayram S, et al. Conservative versus operative treatment of stable thoracolumbar burst fractures in neurologically intact patients: is there any difference regarding the clinical and radiographic outcomes? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020;45:452–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee JY, Vaccaro AR, Lim MR, et al. Thoracolumbar injury classification and severity score: a new paradigm for the treatment of thoracolumbar spine trauma. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:671–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vaccaro AR, Oner C, Kepler CK, et al. AOSpine thoracolumbar spine injury classification system: fracture description, neurological status, and key modifiers. Spine. 2013;38:2028–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schweitzer KM, Vaccaro AR, Harrop JS, et al. Interrater reliability of identifying indicators of posterior ligamentous complex disruption when plain films are indeterminate in thoracolumbar injuries. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12:437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vu C, Gendelberg D. Classifications in brief: AO thoracolumbar classification system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:434–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Giele BM, Wiertsema SH, Beelen A, et al. No evidence for the effectiveness of bracing in patients with thoracolumbar fractures. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:226–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Keynan O, Fisher CG, Vaccaro A, et al. Radiographic measurement parameters in thoracolumbar fractures: a systematic review and consensus statement of the spine trauma study group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:E156–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bizdikian AJ, El Rachkidi R. Posterior ligamentous complex injuries of the thoracolumbar spine: importance and surgical implications. Cureus. 2021;13:e18774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]