Abstract

Dogs’ comprehension of human gestures has been characterized as more human-like than that of our closest primate relatives, due to a level of flexibility and spontaneous performance on par with that of human infants. However, many of the critical experiments that have been the core evidence for an understanding of human communicative intentions in dogs have yet to be replicated. Here we test the ability of dogs to comprehend a pointing gesture while varying the salience of the gesture and the context in which it is made. We find that subjects’ (N = 70) choices across two experiments are consistent with an understanding of communicative intentions. Results largely replicate previous critical controls that rule out a number of egocentric hypotheses including an attraction to human hands and novelty. We also find that dogs spontaneously follow a human gesture in a new context: choosing which direction to navigate around a barrier. The flexible and spontaneous problem solving observed in dogs’ gesture comprehension is discussed in relation to its similarity to that of human infants. We conclude with important avenues for future research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10071-024-01901-6.

Keywords: Pet dogs, Gesture, Intentions, Communication, Cooperation

Dogs’ understanding of human gestural communication has been proposed as more human-like than that observed in nonhuman great apes (Hare and Tomasello 2005a). Human infants, before their first birthday, demonstrate an understanding of communicative intent by flexibly and spontaneously using gestures (Behne et al. 2005, 2012; Call et al. 2004; Morissette et al. 1995; Schulze and Tomasello 2015; Tomasello et al. 2005, 2007, 2022, 2023). Domestic dogs also understand human gestures relatively flexibly and spontaneously from an early age (Duranton et al., 2017; Kaminski et al., 2012; Tauzin et al., 2015; Téglás et al., 2012; Scheider et al., 2013; Lakatos et al., 2009; Bray et al. 2020a; Hare et al., 2010; MacLean et al., 2017; Udell et al., 2008; Wobber and Hare 2009). In contrast, nonhuman great apes show little ability to spontaneously use cooperative communicative gestures as infants or adults (Bräuer et al. 2006; Call et al. 2000; Herrmann et al. 2007; MacLean and Hare 2015; Tempelmann et al. 2013; Tomasello et al. 1997; Wobber et al. 2014; Clark and Leavens 2019). Based on individual differences, dogs and human infants, but not great apes, also show a distinct cognitive factor for cooperative-communication that is distinguished from their non-social problem-solving abilities. Critically, both infants and dogs heavily rely on reading gestures in everyday life. While understanding gestures is a foundation of cultural cognition in infants, in dogs it predicts their training success for service and detection work (Lazarowski et al. 2019; MacLean and Hare 2018; Tomasello 2019).

Based on the similarities between human infants and dogs use of gestures, the communicative intention hypothesis (CIH) was proposed (Agnetta et al. 2000; Hare and Ferrans 2021; Hare and Tomasello 2005b). The CIH suggests that, much like human infants, dogs have evolved the ability to acquire a basic understanding of the cooperative-communicative intention behind human gestures. This understanding gives dogs the potential to solve new problems – some they have never seen before. The CIH predicts dogs will show some spontaneous ability to use novel human gestures and flexibly solve problems with the same human gestures in different contexts (Hare and Ferrans 2021).

A number of alternative interpretations have been proposed for the skills dogs demonstrate. These more cognitively parsimonious hypotheses do not require intention reading. Dogs may simply have an unusual attraction to hands and objects. By this leaner account, dogs egocentrically search for rewards in locations that are near, have been touched or modified by human hands (Bentosela et al. 2008; Dorey et al. 2010; Elgier et al. 2009). As a corollary, dogs may only gradually learn to use pointing as a directional cue through conditioned associations during their extensive experience with humans (Fossi et al. 2014; Hansen Wheat et al. 2022; Wynne et al. 2008). If dogs are relying solely on these types of egocentric motivational or learning mechanisms, their problem solving will be inflexible compared to the intention reading infants. Dogs will struggle to spontaneously use novel gestures – especially those controlling for human proximity. They will also fail to generalize the use of a gesture that is only encoded as a social cue used in one or a few situations (Heyes 1993). Significant experience (dozens or hundreds of repetitions) will be required to relearn the use of a human gesture in each new context a dog encounters (e.g. Anderson et al. 1995; Call et al. 2000; Herrmann et al. 2007; Itakura and Tanaka 1998; Povinelli et al. 1999; Tomasello et al. 1997).

A number of experiments provide evidence against these commonly proposed low-level hypotheses. First, motivation to approach human hands and novel objects does not seem to explain the use of human gestures. For example, in one experiment rewards were hidden in one of two locations directly to the left or right of an adult dog or puppy. A human gestured to the baited location while facing the dog a meter away and remaining equidistant between the two locations. Because the hiding locations were much closer to the dog than the human, when a dog made her choice, she had to move away from the hand being used to gesture in order to approach the reward location. Puppies and adult dogs reliably used the gesture to find the food (Riedel et al., 2008). Further, Agnetta et al. (2000) found that dogs only search for a reward in a location indicated by a novel marker when they observed a human placing it. When subjects did not see the novel marker placed, they searched randomly – ruling out a general attraction to novelty as an explanation for their success (see also Riedel et al., 2008). Second, dogs’ success at reading basic human gestures cannot be fully explained by gradual learning through direct experience either. Young dog puppies, including those without extensive human experience, already succeed at following proximal pointing gestures within the first few months of life (Bhattacharjee et al. 2017; Gácsi et al. 2009; Hare et al. 2002; Riedel et al. 2008; Salomons et al., 2021, 2023). Puppies and adult dogs also comprehend a number of novel communicative gestures – in some cases on their very first trial (Bhattacharjee et al. 2017; Bray et al. 2021; Kaminski et al. 2009; Kirchhofer et al. 2012; Rossano et al. 2014; Salomons et al., 2021; Stewart et al. 2015). This early emerging flexibility is not predicted by a purely associative account, although dogs do improve their use of gestural communication through experience and practice (Elgier et al., 2009; MacLean and Hare 2018; McKinley and Sambrook 2000; Wynne et al., 2008 but see Hare et al. 2010).

While these initial findings seem to rule out a host of lower-level mechanisms, some critical control conditions from Agnetta et al. (2000) and Riedel et al. (2008) have never been replicated. Agnetta et al. (2000) has a relatively small sample (N = 16) by current standards and both sets of experiments were only conducted by a single research group. Given the potential implications for the CIH, it is vital to replicate these experiments with an increased sample, in a different lab and with a different population of dogs (Brecht et al. 2013; Farrar et al. 2021; von Kortzfleisch et al. 2020). Moreover, to further test the idea that dogs have a flexible understanding of the cooperative-communicative intentions behind a human gesture, we need more tests in other contexts beyond the object-choice task.

Here we replicate the previous control conditions designed to test if dogs have an attraction to human hands and novel objects, as well as provide a new test where dogs can use a human gesture in the context of deciding which direction to navigate around a barrier. The CIH predicts that (1) previous findings that rule out several lower-level mechanisms will replicate, and (2) dogs will flexibly interpret the meaning of the same pointing gesture to indicate different actions depending on the problem solving contexts – i.e. to search in a particular location in a hidden-food task, vs. to choose a particular navigational route when faced with a decision of how to get around a barrier.

Experiment 1

To test the CIH we ran two of the critical conditions from Riedel et al. (2008) and Agnetta et al. (2000). To our knowledge they have never been replicated. We first tested the ability of dogs to use a human pointing gesture that requires them to move away from the experimenter’s arm and hand as they make their choice. We then replicated the ABA design from Agnetta et al. (2000) to test if dogs use a physical marker to find hidden food because they are attracted to the object itself or if they attach communicative significance to the object once observing it being placed by an experimenter. The CIH predicts that dogs, as observed previously, will skillfully use the human social gestures but not the non-social marker.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were selected at random from a pool of local companion (i.e. pet) dogs whose owners had entered themselves into the Duke Canine Cognition Center database of potential study participants, filtered for dogs who had no reported history of aggression and were at least one year old. 47 dogs were recruited to participate in the study, but only subjects who completed all trials in all conditions were included in the analysis. 17 dogs did not complete all conditions (see abort criteria in procedure), yielding 30 total subjects included in the analysis. Included subjects ranged in age from 1 to 10 years and were a heterogeneous variety of breeds as reported by owners, including pure-bred and mixed breeds (Table S.1 A).

Procedure

Setup and general procedure

All testing took place in a closed testing room at Duke Canine Cognition Center. All dogs were given a few minutes to explore and acclimate with their owner in the room before testing begins. A white noise machine was on throughout all testing sessions to further reduce any environmental sound distractions. Within the room, the testing area was marked by either tape on the floor or a mat depending on the condition – see Fig. 1 for the distal pointing setup, and Fig. 2 for the marker gesture conditions setup.

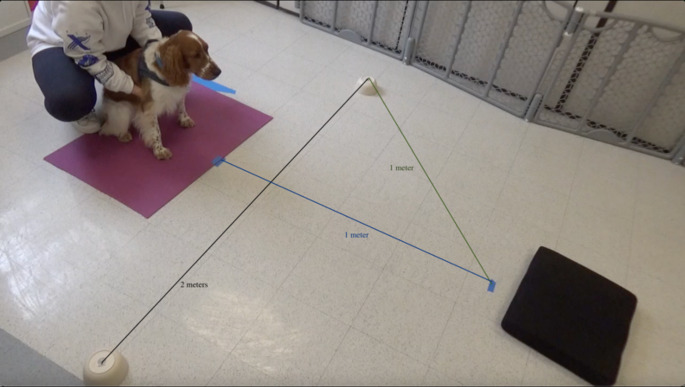

Fig. 1.

Distal Pointing Testing Area

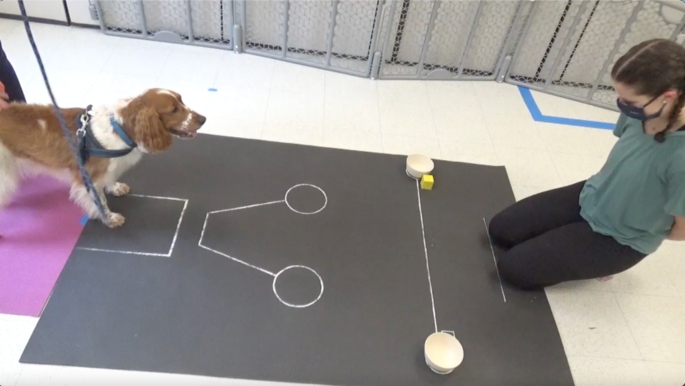

Fig. 2.

Marker Gesture Testing Area

A bowl of fresh water was accessible to the dogs at all times. The rewards used were either Zuke’s Minis treats or an alternative treat provided by the owner, broken down to a similar size. All testing sessions were recorded by two handheld video cameras (Sony Handycam HDR-CX405 or similar), mounted on tripods and positioned outside the testing area at locations which best captured the behaviors of the subject and experimenter for each test.

All subjects completed the conditions in the same order: distal pointing, first non-social marker (NS1), social marker, second non-social marker (NS2). The experimenter was the same person across all subjects and conditions, while the handler was either a research assistant (N = 26) or the owner if the dog demonstrated discomfort with being handled by a stranger or separated from their owner (N = 7). For all trials, the handler (H) positioned the dog on the starting mat, facing forward toward the experimenter (E). E kneeled on the cushion (distal pointing) or painted line (marker) facing the dog. H stood or kneeled behind the dog, looking down towards the floor, and gently restrained them by holding evenly with their hands or by the leash while the E did their demonstration, until E said “Okay!” (or other release word as designated by owner). At this point, H released the dog and started the stopwatch to time the trial. In all trials, dogs had 20 s to make a choice. When the dog made a choice, E or H said “choice”, and H brought the dog back to the starting mat for the next trial. The trials in each condition were presented consecutively, with only the time necessary for the experimenter and handler to reset to the starting position between trials (typically ~ 30 s).

Distal pointing gesture

Warmups

E presented the food to the dog, saying “[dog’s name], look!”. Then E visibly baited one of the bowls by lifting up the side closest to them, sliding their hand under the bowl to place the reward, and lowering it back down. E then returned to kneeling, gazing down at the floor, and gave the release word. The dog needed to successfully choose the baited bowl on four out of five trials in a row to advance to testing.

Test Procedure

E presented the food to the dog, saying “[dog’s name], look!”. Then E, always moving right to left, leaned forward and baited/sham baited each bowl by lifting up the side closest to them, sliding their hand under the bowl to place/sham place the reward, and lowering it back down. E then returned to center, looked and attempted to make eye contact with the dog, and then looked towards the baited bowl, extending contralateral across their body to point at the baited bowl, while saying “[dog’s name], look!”. This position was held for three seconds, then E, while still holding the point, looked back at the dog and gave the release word before returning their gaze to the baited bowl. E held the point and gaze until the dog made a choice. There were six trials in this condition.

Refamiliarization/Abort criteria

If the subject did not make a choice within 20 s, the trial was repeated. If the dog made no choice twice in a row, two refamiliarization warm-up trials were attempted. If at any point there were two more consecutive no choices, a higher value food was used and refamiliarization was attempted again. If the subject did not engage in refamiliarization trials or made four total no-choices within a single task, the session was aborted. In the event that the subject touched the experimenter before making a choice, the trial was repeated. If this occurred more than three times for one trial, the session was aborted.

Marker gesture

Warmups

E presented the food to the dog, saying “[dog’s name], look!”. Then E visibly baited one of the bowls by silently placing the food reward inside. E then returned to kneeling, gazing down at the floor, and gave the release word. The dog must successfully choose the baited bowl on four out of a sliding window of five trials to advance to testing.

Non-Social Condition Test Procedure

H and the dog began the trial outside of the testing room. Before they entered, E placed a food reward in one of the bowls, and then placed the marker (yellow wooden 3” cube, Fig. 2) next to this bowl. E returned to kneeling position and gazed down at the floor, then said “okay” loudly enough for H to hear, at which point H led the dog into the testing room and into position on the starting mat. E looked and attempted to make eye contact with the dog while saying the release word, then returned their gaze to the ground and held this position until the dog made a choice. Dogs completed a total of 12 trials in this condition, in two blocks: six before the social marker gesture condition, and six after.

Social Condition Test Procedure

H and the dog began the trial outside of the testing room. Before they entered, E placed a food reward in one of the bowls. E returned to kneeling position and gazed down at the floor, then said “okay” loudly enough for H to hear, at which point H lead the dog into the testing room and into position on the starting mat. E then presented the marker to the dog by holding it out at arm’s length towards the dog at about the dog’s eye level and attempting to make eye contact while saying, “[dog’s name], look!”, then gazed towards and placed the marker next to the baited bowl while saying “[dog’s name], look!” again. E then looked back at the dog and said the release word, then returned their gaze to the ground and held this position until the dog made a choice. There were six trials in this condition.

Refamiliarization/Abort criteria

If the subject did not make a choice within 20 s, the trial was repeated. If the dog made no-choice (NC) twice in a row, two refamiliarization warm-up trials were attempted. If at any point there were two more consecutive NCs, a higher value reward was used and refamiliarization was attempted again. If the subject did not engage in refamiliarization trials or made four total NCs within a single task, the session was aborted.

Design

This study had a within-group design, and all subjects completed all conditions in the same order. The order of which side was the “correct” baited location was the same for all subjects, and was pseudo-randomized through the battery, so that it was on the right and left an equal number of times in each condition and never on the same side more than twice in a row.

Scoring & Analysis

Subjects’ choices were live-coded by the experimenter after each trial. In all conditions, a “choice” was defined as the first bowl the dog touched or passed their nose over the plane of with their nose or front paw. The dependent measure in each trial was always whether the dog correctly chose the baited bowl. The proportion of correct trials in each condition was then calculated and used for analyses. Testing sessions were video recorded from two angles for later review if needed. However, given the unambiguous nature of the responses and very high reliability found on these same types of two-hiding location choice tasks in prior studies (e.g. Bray et al. 2020a; Riedel et al., 2008; Salomons et al., 2021), reliability assessments of side chosen were not conducted.

In the distal pointing condition, “touching the experimenter” was defined as the dog touching any part of the experimenter’s body with their nose or front paw before making a choice (see repeat/abort criteria). These instances were live-coded when the experimenter felt the touch, and videos of the trials in which touches were reported were later reviewed by a second coder to ensure they were made with the nose or front paw. The second coder was in 100% agreement with the experimenter’s live assessment in these instances.

Analysis was done in RStudio v.1.4.1103. First, mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to (1) look at the overall effect of condition and the other variables of interest (Successes, Failures ~ Condition + Age + Sex + Touch + Handler + (1|Dog Name), family = binomial), and (2) to compare performance on each condition to chance (50%) with a cell means design matrix for condition (Successes, Failures ~ 0 + Condition + (1|Dog Name), family = binomial).

These models were followed up with further tests for each condition and to compare performance in the three marker gesture conditions to one another. One sample t-tests were used as a secondary means of comparing dogs’ performance in each condition to chance, as well as for the first trial only in each condition. A Welch’s T-test was used to compare the performance in the distal pointing condition of the dogs who never touched the experimenter’s hand with that of dogs who touched her hand at least once. The number of individual dogs performing above chance in each condition (determined by a binomial test to be defined as all 6 out of 6 trials correct, p < .05) was also counted. A one-sided p-value for the number of dogs that performed above chance (y) out of the total (n = 30), compared to the predicted number that would do so by chance according to the binomial distribution (when probability of performing above chance is 0.56 = , was also calculated using the following formula:

, was also calculated using the following formula:

An ANOVA was used to test for a significant difference between the three marker gesture conditions (NS1, social, NS2), and then Tukey’s post-hoc tests were performed to determine which of these conditions differed from each other.

Results

A mixed-effects logistic regression model of all conditions and variables of interest revealed a significant effect of condition, with no significant effects of age, sex, whether or not the dog ever touched the experimenter’s hand, or whether the handler was a research assistant or the subject’s owner. Additionally, a mixed-effects logistic regression model with a cell means design matrix for condition revealed that the dogs’ performance was significantly different than chance (50%) on all three conditions (Table S.2 A).

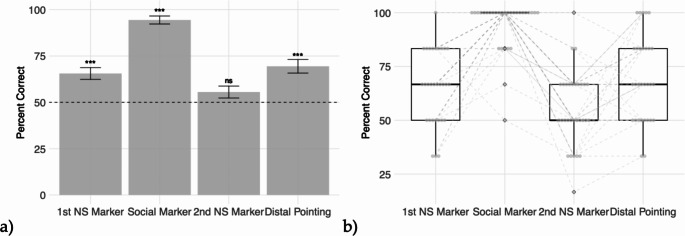

In the first non-social marker condition, the group performed significantly above chance (M = 0.66, SD = 0.17, t(29) = 4.88, p < .001; Fig. 3), though only 1 of the 30 dogs performed significantly above chance as an individual (p = .37). The group also performed significantly above chance on their first trials in this condition (24 of 30 dogs correct, M = 0.80, SD = 0.41, t(29) = 4.04, p < .001).

Fig. 3.

Summary of Gesture Comprehension Performance in Experiment 1. (a) Mean percent of trials correct (±SEM) on each condition. Dashed line represents chance; ***p < .001. (b) Boxplot of data distribution in each condition. Grey points represent individual subjects’ scores, with grey dashed lines linking individuals’ scores across conditions

The group performed significantly above chance at a much higher level in the social marker gesture condition (M = 0.94, SD = 0.12, t(29) = 20.54, p < .001; Fig. 3), and 24 of the 30 dogs performed above chance as individuals (p < .001). All 30 dogs were correct on their first trial in this condition (making a t-test unnecessary/ impossible due to lack of variation).

In the second non-social marker condition, the group did not perform significantly above chance (M = 0.56, SD = 0.18, t(29) = 1.72, p = .10; Fig. 3), and again only 1 of the 30 dogs performed significantly above chance as an individual (this was a different individual than the one above chance in the first non-social marker condition) (p = .37). The group also did not perform above chance on their first trial in this condition (17 of 30 dogs correct, M = 0.57, SD = 0.50, t(29) = 0.72, p = .47.).

Dogs, as a group, performed significantly above chance in the distal pointing condition overall (M = 0.69, SD = 0.20, t(29) = 5.30, p < .001; Fig. 3). The group also performed significantly above chance on their first trials in this condition (25 of 30 dogs correct, M = 0.83, SD = 0.38, t(29) = 4.82, p < .001). At the individual level, 5 of the 30 dogs performed significantly above chance (p < .001). 20 of the 30 dogs included in analysis never touched the experimenter before making a choice during distal pointing trials. For the 10 dogs who did, the total number of repeats across all 6 trials due to touching the experimenter ranged from 1 to 8 (M = 1.23, see Table S.1 A for each subject’s totals).

There was a significant difference in the dogs’ performance on the three marker tasks (F(2, 58) = 46.81, p < .001; one-way repeated measures ANOVA), and post-hoc analyses with a Bonferonni adjustment show that the dogs performed significantly better on the social marker condition than both the first (t(29) = -7.39, p < .001) and second (t(29) = -10.79, p < .001) non-social marker conditions, but that there was no significant difference between the two non-social marker results (t(29) = 2.04, p = .05).

Of the 17 subjects who were recruited for testing but were ultimately excluded from analysis, 13 met the abort criteria for failing to pass the warmups or make choices during trials, three met the abort criteria for repeatedly touching the experimenter’s hand in the distal pointing condition, and one was excluded due to experimenter error during testing.

Discussion

Our results replicate the central findings of Reidel et al. (2008) and Agnetta et al. (2000) with a different group of dogs and double the sample size used in Agnetta et al. (2000). Adult dogs were skilled at using a pointing gesture that required them to move away from the gesturing human and they were much more successful using an arbitrary and novel marker to find food when they observed a human placing it. The performance of subjects in the distal pointing condition was very similar to subjects in Reidel et al. (2008), with both previous and current samples choosing correctly in ~ 70% of trials. Additionally, in the current sample we only included trials in which the dogs did not touch the experimenter before choosing, further supporting the hypothesis that an attraction to hands cannot explain their success. Two-thirds of the dogs tested never touched the experimenter first, and the 1/3 that occasionally did were still able to succeed without doing so, performing at the same level as those who never did. While Agnetta et al. (2000) did not find any evidence that dogs used the marker unless they observed it being placed by a human, our subjects did find the food above chance when they were first tested in the non-social condition. However, they performed far more skillfully when seeing the marker placed, performed at chance in the repeat of the nonsocial condition, and did not perform differently in the two nonsocial sessions. At the individual level, only a single subject (3% of the sample) performed above chance in either nonsocial marker condition, while over 75% did so in the social marker condition. Finally, their success rate on the first trial of the first non-social marker condition was higher than both their average performances across all 6 trials in the non-social conditions and their first-trial success rate in the second non-social condition. This suggests our subjects (1) had a relatively weak initial attraction to the marker in their first session which dwindled and disappeared by the second session and (2) did not attach any social or communicative meaning to the marker itself. The difference in performance here from Agnetta et al. (2000) might be a result of the placement of the marker in the two different experiments. In Agnetta et al. (2000) the marker was placed on top of the hiding locations and may not have been as salient as when it was placed next to hiding location in the current experiment – potentially drawing more attention to it. Finally, our subjects’ high level of performance with the arbitrary and novel marker when used in a social gesture, with 100% using it correctly on the first trial and over 75% making only correct choices, can be characterized as rapid and spontaneous comprehension. Future studies can further examine factors that make the marker gesture so salient for most dogs in comparison to other gestures.

Overall, our findings strengthen the evidence against attraction to hands or novel objects as lower-level explanations for dogs’ success in gesture tasks and support the hypothesis that the social, communicative aspect of the gesture is key to dogs’ ability to use it effectively. In Experiment 2, we further test the flexibility and spontaneity of dogs’ comprehension of human pointing gestures.

Experiment 2

In this experiment we will use three different conditions to test the comprehension of subjects by varying the salience of a pointing gesture and the context of its use. All subjects will be tested for their ability to locate rewards using the highly salient proximal pointing gesture and the more subtle momentary pointing gesture. In addition, they will be presented with a barrier which they must navigate around in order to obtain a reward. We will measure if subjects prefer to detour the barrier using the direction suggested by a human pointing – even though subjects will be rewarded regardless of their direction of approach.

The CIH predicts that while individual dogs may show varying success across the different gesture types or contexts, as a group, the dogs will be able to succeed with all gestures and many subjects should succeed as individuals regardless of the salience of the pointing gesture or the context in which it is made. The CIH also predicts that dogs will be able to switch between responses to a pointing gesture based on the context of the problem presented: to locate a specific place or choose a direction to navigate around a barrier. Alternatively, success in one context may hamper performance in another, as a dog’s memory of being rewarded in one context, prevents success in the other.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were an experimentally naive set of individuals that did not participate in Experiment 1 but were selected from the same subject pool using the same process. 51 dogs were recruited to participate in the study, but only subjects who completed all trials in all conditions were included in the analysis. Eleven dogs did not complete all conditions (see abort criteria in procedure), leaving 40 total subjects included in the analysis. Subjects represented a heterogeneous sample of breeds ranging in age from 1 to 13 years (Table S.1B). All dogs were handled by the same research assistant (N = 30) unless they appeared nervous when their owner left the room, in which case they were handled by their owner (N = 10).

Procedure

The general procedures were the same as described for Experiment 1.

Setup

The testing area was delineated using a testing mat (Fig. 4). For the proximal pointing condition, the bowl locations were marked with tape on the floor outside the edges of the testing mat, 2 m apart from one another, on the same line that is 1 m from the start box. Large dogs started centered behind, rather than centered in, the starting box so that they could not see over the barrier when applicable.

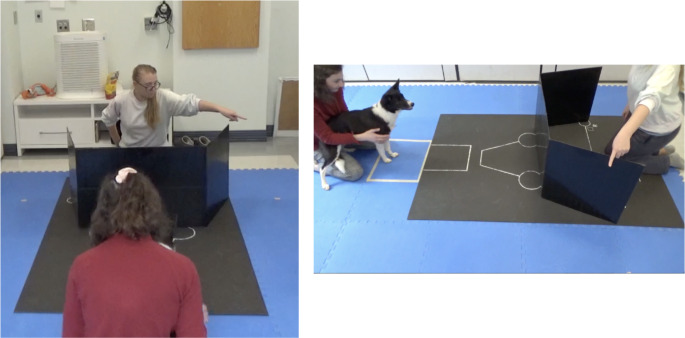

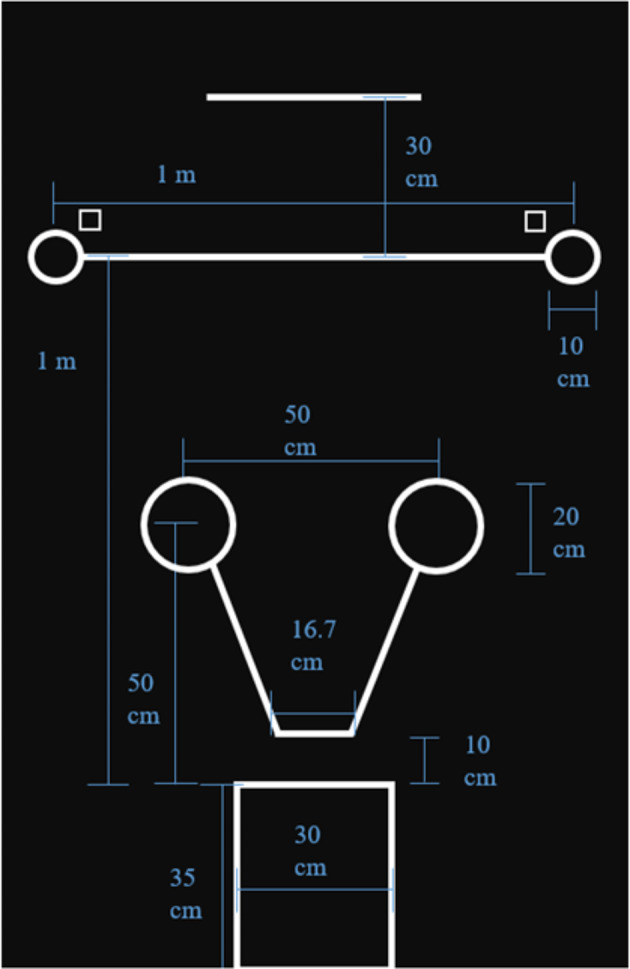

Fig. 4.

Testing Mat Dimensions

Two-Bowl Choice Warmups

Before beginning the two-bowl choice conditions (whether proximal or momentary pointing came first), all subjects were required to succeed in four out of five warmup trials, identical to those described for the Marker Gesture warmups in Study 1.

Proximal pointing

E approached the subject to present the food reward in her hand and said “look!”, allowing the dog to see and sniff the food briefly, saying “[dog’s name], look!”. E then closed her fingers around the food and rotated her wrist so that the back of her hand faced the subject, occluding the food. With the reward occluded, E then walked backwards to the bowl at position R, bent down and either placed or pretended to place (as appropriate for the trial) the food in the bowl, then walked across to and did the same at the bowl at position L, making identical hand movements and sounds at each bowl. E then knelt behind the center line. E knelt bent forward to eye level with the subject, and pointed with her proximal arm to the baited bowl, index finger extended and head turned toward the baited bowl. E then turned her head to look at the subject, said “look!”, and turned her head back towards the baited bowl gaze alternating this way three times, all while maintaining the pointing arm’s position. E then said “Okay!” and maintained the pointing gesture and gazed towards the baited bowl until the trial ended.

Momentary pointing

E places both bowls next to each other in the center of the 1-m line between the 10-cm circles. The occluder is ~ 10 cm in front of bowls, blocking the dog’s view of the bowls. E presents the subject with the reward (saying “[dog’s name], look!”), places the treat in one of the bowls behind the occluder while simultaneously sham baiting the other bowl with the other hand (i.e. mimicking the baiting movement with the empty hand). E then places the occluder behind her and simultaneously slides the bowls into the positions marked on the mat. As E slides the bowls into the 10-cm circles, she glances first to the bowl on her left, and then to the bowl on her right to check bowl placement. E spends equal time glancing at each bowl placement and always in left-right sequence. After baiting, E tries to make eye contact with the dog, says “[dog’s name], look!”, and points toward the bowl with the reward. The point consists of the index finger of the contralateral hand extended about 20 cm from the bowl (other hand should already be behind E’s back) and E’s head and gaze directed toward the bowl. This point was held for ~ two seconds and then E placed hand behind back and looked down. E then gave an “okay!” and remained in this position until trial ended.

Barrier warmups

E presents the food in the bowl to the dog, saying “[dog’s name], look!”. Then E immediately gives the release word and uses the bowl to guide the dog around the barrier, placing the bowl down in the center behind the barrier and leaning back into kneeling position to allow the dog to retrieve the reward. This is repeated as needed until the dog succeeds at following the bowl around the barrier and gets the reward twice, once from the right side and once from the left.

Barrier pointing

The testing area layout for the barrier pointing condition is pictured below (Fig. 5), with the front edge of the barrier aligned with the top of the circles 50 cm from the start box. E presented the food to the dog, saying “[dog’s name], look!”. Holding the bowl centered above the barrier so it was visible to the dog, E audibly and visibly dropped the food into the bowl and then lowered it straight down behind the barrier, following it with her gaze and placing it in the same spot where the dog had retrieved it during warm ups. E then looked back up at the dog, attempted to make eye contact, and said “this way!” as she pointed over the side of the barrier and gazed out over the barrier towards her finger. This position was held for three seconds, and then E said the release word. Once the dog had picked a side to navigate around the barrier and was about to come around the barrier’s edge, E put their arm back down behind their back.

Fig. 5.

Barrier Condition Testing Area

Refamiliarization/Abort criteria

If the subject did not make a choice within 20 s, the trial was repeated. If there were two no choices twice in a row, two refamiliarization warm-up trials were attempted. If at any point there were two more consecutive no choices, a higher value reward was used and refamiliarization was attempted again. If the subject did not engage in refamiliarization trials or made four total no choices within a single task, the session was aborted. Because touching the experimenter was uncommon and did not affect performance in Experiment 1, it was not part of the abort criteria for Experiment 2.

Design

All subjects received six trials in each of the three conditions for a total of 18 test trials. This study had a within-group design. The order of the two object-choice pointing conditions was counterbalanced, with half of the subjects completing the proximal pointing condition first, and half completing the momentary pointing condition first. The barrier pointing condition was done in a separate testing session, and the order was counterbalanced so that half the subjects participated in the barrier condition before the two object choice conditions while the other half completed it after the object choice pointing conditions. There was always a play and/or outside relief break of at least 5 min in between the barrier pointing session and the two-bowl choice pointing session. The side baited on the first trial was counterbalanced across subjects so that half received each side first. Throughout the test sessions baiting was pseudo-randomized so that the reward was hidden in the right and left an equal number of times in each condition and never on the same side more than twice in a row.

Scoring & analysis

The approach to scoring and analysis was identical to Experiment 1.

First, mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to (1) look at the overall effect of condition and the other variables of interest (Successes, Failures ~ Condition + Age + Sex + Order + Handler + (1|Dog Name), family = binomial) and (2) to compare performance on each condition to chance (50%) with a cell means design matrix for condition (Successes, Failures ~ 0 + Condition + (1|Dog Name), family = binomial).

These models were followed up with further tests for each condition and to compare performance in the three marker gesture conditions to one another. One sample t-tests were used as a secondary means of comparing dogs’ performance in each condition to chance, as well as for the first trial only in each condition. All three conditions were examined for whether subjects performed above chance as a group (across all trials and on Trial 1) and as individuals, and the p-value for the number of individuals performing above chance was also calculated according to the same formula used in Experiment 1 (n = 40). A Welch’s t-test was performed to test for difference in performance between the proximal and momentary pointing conditions. Welch’s T-tests were also performed to test for an effect of session order (barrier session first or object-choice session first) on performance in each condition.

Results

A mixed-effects logistic regression model of all conditions and variables of interest revealed a significant effect of condition, with no significant effects of age, sex, session order, or whether the handler was the research assistant or the subject’s owner. Additionally, a mixed-effects logistic regression model with a cell means design matrix for condition revealed that the dogs’ performance was significantly different than chance (50%) on all three conditions (Table S.2B).

In the barrier pointing condition, the group performed significantly above chance (M = 0.78, SD = 0.19, t(39) = 8.94, p < .001; Fig. 6), and at the individual level, 11 of the 40 dogs performed significantly above chance (p < .001). The group also performed significantly above chance on their first trials in this condition (28 of 40 dogs correct, M = 0.7, SD = 0.46, t(39) = 2.73, p < .01). In the momentary pointing condition, the group performed significantly above chance (M = 0.7, SD = 0.21, t(39) = 5.81, p < .001; Fig. 6), and at the individual level, 7 of the 40 dogs performed significantly above chance (p < .001). The group did not perform significantly above chance on their first trials in this condition (24 of 40 dogs correct, M = 0.6, SD = 0.5, t(39) = 1.27, p = .21). In the proximal pointing condition, the group performed significantly above chance (M = 0.89, SD = 0.16, t(39) = 15.67, p < .001; Fig. 6), and at the individual level, 24 of the 40 dogs performed significantly above chance (p < .001). The group also performed significantly above chance on their first trials in this condition (35 of 40 dogs correct, M = 0.88, SD = 0.33, t(39) = 7.08, p < .001).

Fig. 6.

Summary of Gesture Comprehension Performance in Experiment 2. (a) Mean percent of trials correct (± SEM) on each condition. Dashed line represents chance; ***p < .001. (b) Boxplot of data distribution in each condition. Grey points represent individual subjects’ scores, with grey dashed lines linking individuals’ scores across conditions

A two-way mixed ANOVA shows that there was a significant difference in performance between the three pointing conditions [F(2,76) = 12.39, p < .001, generalized eta squared = 0.159], and no significant differences between the session orders (barrier session before vs. after object choice session) [F(1,38) = 2.24, p = .14, generalized eta squared = 0.024] or interaction between session order and condition [F(2,76) = 0.155, p = .85, generalized eta squared = 0.002]. Post-hoc analyses with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that there was no significant difference between the momentary pointing and barrier pointing conditions (t(39) = 1.73, p = .09) while momentary pointing (t(39) = -5.13, p < .001) and barrier pointing (t(39) = -3.61, p < .001) were each significantly different from the proximal pointing condition.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that as a group, subjects showed the predicted flexibility by interpreting all three gestures successfully, despite differences in their saliency and contexts. Even though subjects were only given six trials in each condition, they were able to comprehend a human pointing gesture in each condition. The three different tasks did reveal significant individual variability. Relatively few dogs performed perfectly on any of the tasks. While 60% of subjects were above chance as individuals when responding to proximal pointing, the most salient gesture, only 17–28% of individuals chose correctly in all six trials of the momentary or barrier pointing. Only 30% of subjects scored perfectly on two or more of the gestures, with just 3 of the 40 dogs using all three gestures without making a mistake. Finally, the lack of an order effect suggests that at the group level, switching between contexts did not impact performance significantly. Overall, the results support the CIH in showing how dogs can flexibly and spontaneously comprehend human pointing gestures across contexts. However, by limiting the number of trials each subject received, our criteria for individual success was relatively strict. This strict criterion reveals important individual variability. Some dogs can flawlessly switch between contexts, while other dogs are more affected by the saliency of the cue (as demonstrated by the variation in number of successful individuals in each condition). Future research can provide dogs with more trials to examine if more dogs will succeed as individuals with more room for mistakes. It may also be useful to collect detailed survey information from owners that may help reveal which, if any, characteristics (breeding, special training or participation in sport, frequent use of pointing gestures at home, etc.) may shape these individual differences and allow some dogs to generalize more readily. Further study could also untangle exactly which elements of the gesture used in the proximal condition made it easier for many dogs to read.

General discussion

The ability of dogs to spontaneously use a variety of human pointing gestures of different salience across multiple contexts provides strong support for the Communicative Intentions Hypothesis. Our subjects’ success with distal, proximal, and momentary pointing corroborates previous findings that dogs can successfully utilize different variations of a pointing gesture in the context of searching for hidden food. Their performance can largely be described as flexible and spontaneous. Dogs showed flexibility since they could comprehend a human across contexts – searching and detouring. Their performance was spontaneous since there were so few trials per test session with little opportunity to learn within the test and as a group the dogs were above chance on their first trial in all gesture conditions except the momentary pointing. At the individual level many subjects showed as much or more skill with the novel and arbitrary social marker gesture than with a more familiar pointing gesture. Our newest barrier task further shows that adult dogs can interpret the same gesture across different contexts, without explicit training within the experiment (see also Kirchhofer et al. (2012); Rossano et al. (2014). Rather than searching in a location on the floor, in this new context, dogs moved towards the indicated side of the barrier and continued around it, away from the pointing hand, to where food was located. The order the dogs were tested in the two contexts also did not affect their performance. Our subjects easily transition between the different communicative contexts.

Results only provided limited evidence to support the role of lower-level explanations like an attraction to human hands or novel objects impacting subjects’ choices. Replicating previous findings from Riedel et al. (2008), performance with the distal pointing condition rules out an attraction to a human hand as a viable explanation for success. The dogs were still able to successfully use a human gesture, even when they had to move away from the hand to choose correctly. In addition to this replication, we also added an additional procedural control to the distal pointing condition of Experiment 1 to prevent any influence on results of a subject’s attraction to hands. Trials were excluded and rerun, if the subject approached or touched the experimenter’s hand during the trial. Although it occurred rarely, this procedure eliminated the possibility of performance being influenced by an attraction to the hand that led subjects to search in the bowl that happened to be nearest (see also Salomons et al. (2023).

Unlike Agnetta et al. (2000), our subjects did have a slight but significant initial attraction to the novel marker in first nonsocial marker condition. In the first block, 80% of subjects chose the marker location on the first trial, and 64% chose the marker location across all six trials. Yet in the second block, subjects chose at chance levels on both the first trial and across all six. The group’s performance on the first nonsocial marker condition did not differ significantly from that of the second non-social marker session. These results are consistent with an initial attraction to the marker that extinguished quickly. Otherwise, there was little difference between the first and second blocks of the non-social marker condition. Only one subject performed above chance in each block (different individuals). Subjects also made correct choices significantly more with the social marker than either of the two nonsocial marker conditions – and by a large margin of over 30% points (an effect similar in size to that observed in Agnetta et al. (2000). Even if the attraction dogs show in the first nonsocial marker condition was maintained it is not strong enough to explain the level of skill dogs show with the social marker where they were correct in 95% of trials. Our subjects’ pattern of results also rules out a simple associative account linking the marker and the reward since the subjects failed to use the marker in the second nonsocial marker test even though they were just rewarded for searching the marked location in the social marker condition.

Our two experiments are not without limitations. Our sample of dogs may not be representative of all dogs, or even all companion dogs. Our subjects are selected to visit our university campus center based on their confidence in novel situations. Any dog with behavioral “problems” are not tested (i.e. aggression, fear, lack of food motivation, etc.). This selection might introduce sampling bias that masks variability in performance present in dogs as a species (e.g. free ranging dogs, dingos, etc.). While we did match or increase our sample size compared to previous publications, it may still be that robust differences in certain dog populations’ abilities remain unseen within our current sample. We also provide no developmental tests. This leaves open the possibility that the high performance of some dogs on some tasks are heavily shaped by extensive early exposure to humans that allowed for a relatively gradual maturational or learning process (although unlikely in the case of the social marker; Bray et al., 2021b; Salomons et al., 2021). It will be important for future work to explore how gesture comprehension across contexts matures as dogs develop and how cognitive emergence interacts with experience to improve their abilities through different forms of learning. We also only examined one additional context. Our results suggest that future work should continue to explore the limits of flexibility in dogs’ gesture comprehension beyond search, retrieval, and detour that have previously been demonstrated.

While the current research helps reinforce the idea that dogs comprehend human gestures in a relatively human-like way (compared to other nonhumans), it still remains unclear to what degree dogs understanding of communicative intentions is like what is observed in young infants. Dogs are similar in important ways, but any basic understanding they have of communicative intentions is likely to be highly constrained compared to infants who are soon to become linguistic.Tomasello 2019 outlines a range of social inferences that infants make while cooperatively communicating with others that are critical non-linguistic precursors of human language abilities. It is likely that many of these inferential abilities are well beyond what dogs are capable of. For example, dogs are likely incapable of exclusionary inference where a child infers that an adult’s gesture refers to one aspect of an object instead of the whole(Moll et al. 2006; see also MacLean & Hare, 2012 for an example in great apes). And no one has ever reported the understanding of iconic gestures by dogs (or any other nonhuman; Tomasello 2019; but see Kaminski et al. (2009) for more on non-gestural icons). There is also little, if any, evidence in dogs for a link between the comprehension and production of pointing that is another indication of a human infant’s understanding of shared intentions (Behne et al. 2012). Important for the future will be systematically characterizing the similarity and differences between dog and human understanding of communicative intentions.

Overall, we replicated the main findings from the two experiments most frequently cited as evidence against egocentric interpretations of the use of human gestures by dogs. We again found evidence that dogs’ understanding of human gestures is flexible, spontaneous, and cannot be explained by lower-level mechanisms alone. This supports the previous hypothesis that dogs’ understanding of cooperative communication is human-like in its underlying cognition, opening avenues for the study of evolutionary processes that may have given rise to these abilities in both species (Hare 2017). It will also be exciting to explore if individual differences in flexible understanding of communicative intentions explains differences in trainability or performance among companion and working dogs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Candler Cusato and Morgan Ferrans for assistance with recruiting participants, Mike Tomasello for helpful comments throughout, and the many undergraduate research assistants who helped with dog handling (especially Samantha Kefer).

Author contributions

All authors conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. H.S. and J.S. conducted the investigation. H.S. and B.H. wrote the original manuscript text. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded in part by grants from the Office of Naval Research (N00014-16-12682), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH-1RO1HD097732) and the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation (Grant-#02700).

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information file.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This work was conducted under Duke University IACUC protocol A128-23‐06.

Disclosure

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agnetta B, Hare B, Tomasello M (2000) Cues to food location that domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) of different ages do and do not use. Anim Cogn. 10.1007/s100710000070 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR, Sallaberry P, Barbier H (1995) Use of experimenter-given cues during object-choice tasks by capuchin monkeys. Anim Behav 49(1):201–208. 10.1016/0003-3472(95)80168-5 [Google Scholar]

- Behne T, Carpenter M, Tomasello M (2005) One-year-olds comprehend the communicative intentions behind gestures in a hiding game. Dev Sci 8(6):492–499. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behne T, Liszkowski U, Carpenter M, Tomasello M (2012) Twelve-month-olds’ comprehension and production of pointing. Br J Dev Psychol. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentosela M, Barrera G, Jakovcevic A, Elgier AM, Mustaca AE (2008) Effect of reinforcement, reinforcer omission and extinction on a communicative response in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Behavioural Processes, 78(3), 464–469. 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee D, Gupta NND, Sau S, Sarkar S, Biswas R, Banerjee A, Babu A, Mehta D, D., Bhadra A (2017) Free-ranging dogs show age related plasticity in their ability to follow human pointing. PLoS ONE 12(7):e0180643. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuer J, Kaminski J, Riedel J, Call J, Tomasello M (2006) Making inferences about the location of hidden food: Social dog, causal ape. J Comp Psychol. 10.1037/0735-7036.120.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EE, Gruen ME, Gnanadesikan GE, Horschler DJ, Levy KM, Kennedy BS, Hare BA, MacLean EL (2020a) Cognitive characteristics of 8- to 10-week-old assistance dog puppies. Anim Behav 166:193–206. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EE, Gruen ME, Gnanadesikan GE, Horschler DJ, Levy KM, Kennedy BS, Hare BA, MacLean EL (2020b) Dog cognitive development: a longitudinal study across the first 2 years of life. Anim Cogn. 10.1007/s10071-020-01443-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EE, Gnanadesikan GE, Horschler DJ, Levy KM, Kennedy BS, Famula TR, MacLean EL (2021) Early-emerging and highly heritable sensitivity to human communication in dogs. Curr Biol 31(14):3132–3136e5. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht KF, Legg EW, Nawroth C, Fraser H, Ostojić L (2013) The Status and Value of replications in Animal Behavior Science. 10.26451/abc.08.02.01.2021

- Call J, Agnetta B, Tomasello M (2000) Cues that chimpanzees do and do not use to find hidden objects. Anim Cogn 3(1):23–34. 10.1007/S100710050047/METRICS [Google Scholar]

- Call J, Hare B, Carpenter M, Tomasello M (2004) Unwilling’ versus ‘unable’: chimpanzees’ understanding of human intentional action. Dev Sci 7(4):488–498. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark H, Leavens DA (2019) Testing dogs in ape-like conditions: the effect of a barrier on dogs’ performance on the object-choice task. Animal Cognition 22(6):1063–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dorey NR, Udell MAR, Wynne CDL (2010) When do domestic dogs, Canis familiaris, start to understand human pointing? The role of ontogeny in the development of interspecies communication. Anim Behav 79(1):37–41. 10.1016/J.ANBEHAV.2009.09.032 [Google Scholar]

- Elgier AM, Jakovcevic A, Barrera G, Mustaca AE, Bentosela M (2009) Communication between domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and humans: Dogs are good learners. Behavioural Processes, 81(3), 402–408. 10.1016/J.BEPROC.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Farrar BG, Voudouris K, Clayton NS (2021) Replications, comparisons, sampling and the Problem of Representativeness in Animal Cognition Research. Anim Behav Cognition 8(2):273. 10.26451/ABC.08.02.14.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossi MC, Coppola D, Baini M, Giannetti M, Guerranti C, Marsili L, Panti C, De Sabata E, Clò S (2014) Large filter feeding marine organisms as indicators of microplastic in the pelagic environment: the case studies of the Mediterranean basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar Environ Res 100:17–24. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gácsi M, Györi B, Virányi Z, Kubinyi E, Range F, Belényi B, Miklósi Á (2009) Explaining dog wolf differences in utilizing human pointing gestures: selection for synergistic shifts in the development of some social skills. PLoS ONE 4(8). 10.1371/journal.pone.0006584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hansen Wheat C, van der Bijl W, Wynne CDL (2022) Rearing condition and willingness to approach a stranger explain differences in point following performance in wolves and dogs. Learn Behav 31:1–4. 10.3758/S13420-022-00544-2/FIGURES/1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare B (2017) Survival of the Friendliest: Homo sapiens Evolved via Selection for Prosociality. In Annual Review of Psychology. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044201 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hare B, Ferrans M (2021) Is cognition the secret to working dog success? In Animal Cognition (Vol. 24, Issue 2, pp. 231–237). Springer. 10.1007/s10071-021-01491-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hare B, Tomasello M (2005a) Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends Cogn Sci 9(9):439–444. 10.1016/j.tics.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare B, Tomasello M (2005b) The emotional reactivity hypothesis and cognitive evolution. Trends Cogn Sci. 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.01016061417 [Google Scholar]

- Hare B, Brown M, Williamson C, Tomasello M (2002) The domestication of social cognition in dogs. Sci (Vol 298. Issue 5598). American Association for the Advancement of Science10.1126/science.1072702 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hare B, Rosati A, Kaminski J, Bräuer J, Call J, Tomasello M (2010) The domestication hypothesis for dogs’ skills with human communication: a response to Udell (2008) and Wynne (2008). Animal Behaviour, 79(2), 1–6. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.06.031

- Herrmann E, Call J, Hernández-Lloreda MV, Hare B, Tomasello M (2007) Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: the cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science 317(5843):1360–1366. 10.1126/science.1146282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes CM (1993) Imitation, culture and cognition. Anim Behav 46(5). 10.1006/anbe.1993.1281

- Itakura S, Tanaka M (1998) Use of experimenter-given cues during object-choice tasks by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), an orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), and human infants (Homo sapiens). J Comp Psychol 112(2):119–126. 10.1037/0735-7036.112.2.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski J, Tempelmann S, Call J, Tomasello M (2009) Domestic dogs comprehend human communication with iconic signs. Dev Sci. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhofer KC, Zimmermann F, Kaminski J, Tomasello M (2012) Dogs (canis familiaris), but not chimpanzees (pan troglodytes), understand imperative pointing. PLoS ONE 7(2):30913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski L, Rogers B, Waggoner LP, Katz JS (2019) When the nose knows: ontogenetic changes in detection dogs’ (Canis familiaris) responsiveness to social and olfactory cues. Anim Behav 153:61–68. 10.1016/J.ANBEHAV.2019.05.002 [Google Scholar]

- MacLean EL, Hare B (2015) Bonobos and chimpanzees exploit helpful but not prohibitive gestures. Behaviour 152(3–4):493–520. 10.1163/1568539X-00003203 [Google Scholar]

- MacLean EL, Hare B (2018) Enhanced selection of assistance and explosive detection dogs using cognitive measures. Front Veterinary Sci 5(OCT). 10.3389/fvets.2018.00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- MacLean EL, Herrmann E, Suchindran S, Hare B (2017) Individual differences in cooperative communicative skills are more similar between dogs and humans than chimpanzees. Anim Behav 126:41–51. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.01.005 [Google Scholar]

- McKinley J, Sambrook TD (2000) Use of human-given cues by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and horses (Equus caballus). Anim Cogn 3(1):13–22. 10.1007/s100710050046 [Google Scholar]

- Moll H, Koring C, Carpenter M, Tomasello M (2006) Infants determine others’ focus of attention by Pragmatics and Exclusion. J Cognition Dev 7(3):411–430. 10.1207/S15327647JCD0703_9 [Google Scholar]

- Morissette P, Ricard M, Décarie TG (1995) Joint visual attention and pointing in infancy: a longitudinal study of comprehension. Br J Dev Psychol 13(2):163–175. 10.1111/j.2044-835x.1995.tb00671.x [Google Scholar]

- Povinelli DJ, Bierschwale DT, Čech CG (1999) Comprehension of seeing as a referential act in young children, but not juvenile chimpanzees. Br J Dev Psychol 17(1):37–60. 10.1348/026151099165140 [Google Scholar]

- Riedel J, Schumann K, Kaminski J, Call J, Tomasello M (2008) The early ontogeny of human-dog communication. Anim Behav 75(3):1003–1014. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.08.010 [Google Scholar]

- Rossano F, Nitzschner M, Tomasello M (2014) Domestic dogs and puppies can use human voice direction referentially. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1785), 20133201. 10.1098/rspb.2013.3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salomons H, Smith KCM, Callahan-Beckel M, Callahan M, Levy K, Kennedy BS, Bray EE, Gnanadesikan GE, Horschler DJ, Gruen M, Tan J, White P, vonHoldt BM, MacLean EL, Hare B (2021a) Cooperative Communication with humans evolved to Emerge Early in Domestic Dogs. Curr Biol 31(14):3137–3144e11. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomons H, Smith KCM, Callahan-Beckel M, Callahan M, Levy K, Kennedy BS, Bray EE, Gnanadesikan GE, Horschler DJ, Gruen M, Tan J, White P, vonHoldt BM, MacLean EL, Hare B (2023) Response to hansen wheat et al.: additional analysis further supports the early emergence of cooperative communication in dogs compared to wolves raised with more human exposure. Learning & Behavior, 51(2), 131–134. 10.3758/s13420-023-00576-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schulze C, Tomasello M (2015) 18-month-olds comprehend indirect communicative acts. Cognition 136:91–98. 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart L, MacLean EL, Ivy D, Woods V, Cohen E, Rodriguez K, McIntyre M, Mukherjee S, Call J, Kaminski J, Miklósi Á, Wrangham RW, Hare B (2015) Citizen science as a new tool in dog cognition research. PLoS ONE. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempelmann S, Kaminski J, Liebal K (2013) When apes point the finger: three great ape species fail to use a conspecific’s imperative pointing gesture. Interact Stud 14(1). 10.1075/is.14.1.02tem

- Tomasello M (2019) Becoming human: a theory of ontogeny. Belknap Press of Harvard University

- Tomasello M (2022) The evolution of agency: behavioral organization from lizards to humans. MIT Press

- Tomasello M (2023) Having intentions, understanding intentions, and understanding communicative intentions. Developing theories of intention. Psychology, pp 63–76

- Tomasello M, Call J, Gluckman A (1997) Comprehension of Novel communicative signs by apes and human children. Child Dev 68(6):1067–1080 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, Moll H (2005) Understanding and sharing intentions: the origins of cultural cognition. Behav Brain Sci 28(5):675–691. 10.1017/S0140525X05000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Liszkowski U (2007) A new look at infant pointing. Child Dev 78(3):705–722. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kortzfleisch VT, Karp NA, Palme R, Kaiser S, Sachser N, Richter SH (2020) Improving reproducibility in animal research by splitting the study population into several ‘mini-experiments’. Sci Rep 10(1):16579. 10.1038/s41598-020-73503-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobber V, Hare B (2009) Testing the social dog hypothesis: are dogs also more skilled than chimpanzees in non-communicative social tasks? Behav Process 81(3):423–428. 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobber V, Herrmann E, Hare B, Wrangham R, Tomasello M (2014) Differences in the early cognitive development of children and great apes. Dev Psychobiol 56(3):547–573. 10.1002/dev.21125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne CDL, Udell MAR, Lord KA (2008) Ontogeny’s impacts on human-dog communication. Anim Behav 76(4):1–4. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.03.010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the supplementary information file.