Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Blood pressure (BP) control is essential for preventing cardiorenal complications in chronic kidney disease (CKD), but most patients fail to reach BP target. We assessed longitudinal patterns of antihypertensive drug prescription and systolic BP.

Study Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Setting & Population

In total, 2,755 hypertensive patients with CKD stages 3-4, receiving care from a nephrologist, from the French CKD–Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (CKD-REIN cohort study).

Exposure

Patient factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, and laboratory data, and provider factors, including number of primary care physician and specialist encounters.

Outcomes

Changes in antihypertensive drug-class prescription during follow-up: add-on or withdrawal.

Analytical Approach

Hierarchical shared-frailty models to estimate hazard ratios (HR) to deal with clustering at the nephrologist level and linear mixed models to describe systolic BP trajectory.

Results

At baseline, median age was 69 years, and mean estimated glomerular filtration rate was 33 mL/min/1.73 m². In total, 66% of patients were men, 81% had BP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg, and 75% were prescribed ≥2 antihypertensive drugs. During a median 5-year follow-up, the rate of changes of antihypertensive prescription was 50 per 100 person-years, 23 per 100 for add-ons, and 25 per 100 for withdrawals. After adjusting for risk factors, systolic BP, and the number of antihypertensive drugs, poor medication adherence was associated with increased HR for add-on (1.35, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01-1.80), whereas a lower education level was associated with increased HR for withdrawal (1.23, 95% CI, 1.02-1.49) for 9-11 years versus ≥12 years. More frequent nephrologist visits (≥4 vs none) were associated with higher HRs of add-on and withdrawal (1.52, 95% CI, 1.06-2.18; 1.57, 95% CI, 1.12-2.19, respectively), whereas associations with visit frequency to other physicians varied with their specialty. Mean systolic BP decreased by 4 mm Hg following drug add-on but tended to increase thereafter.

Limitations

Lack of information on prescriber and drug dosing.

Conclusions

In patients with CKD and poor BP control, changes in antihypertensive drug prescriptions are common and relate to clinician preferences and patients’ tolerability. Sustainable reduction in systolic BP after add-on of a drug class is infrequently achieved.

Index Words: chronic kidney disease, hypertension, blood pressure, antihypertensive agents, renin-angiotensin system

Plain-Language Summary

Blood pressure (BP) control remains unattained in most patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), raising questions about how antihypertensive treatment is managed. Our study highlights dynamic, yet heterogeneous patterns of antihypertensive drug prescriptions in patients with CKD stages 3-4 receiving care from a nephrologist over 5 years of follow-up. Modifiable factors such as high body mass index and poor medication adherence were associated with higher hazard of adding-on an antihypertensive drug class, independently of baseline BP and antihypertensive treatment. Similarly, lower education level was associated with antihypertensive drug withdrawn, as was more frequent visits to primary care physicians, underlining the importance of coordinated care. Sustainable reduction in systolic BP after add-on of a drug class is infrequently achieved and may be related to drug withdrawal and poor treatment adherence.

Hypertension is the leading modifiable risk factor for premature death, affecting 1.4 billion people worldwide.1 A possible cause and consequence of chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension is also its most common comorbid condition.2,3 Strict blood pressure (BP) control unambiguously improves survival and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes in this population.4, 5, 6, 7 Guidelines recommend systolic BP levels from 130-139 to <120 mm Hg in CKD,8, 9, 10 but these targets are not met by many patients, with considerable international variation.11

Achieving adequate BP control most often requires associating 2 or more antihypertensive drug classes.12,13 Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors are recommended as first-line treatment in patients with CKD, more effective than active controls in improving kidney and CV outcomes.8, 9, 10 Absent other compelling indications or contraindications, calcium-channel blockers (CCBs) and diuretics are interchangeably recommended as second- and third-line drugs, but evidence for preferring one or the other lacks consistency.9,10,14, 15, 16 The management of hypertension in patients with CKD is complex because of their multiple comorbid conditions and prescriptions for which different drug classes may be contraindicated or poorly tolerated, and prescribers may have preferences.17

In a nationally representative CKD cohort with poor BP control, we hypothesized that antihypertensive treatment is rarely reassessed. We comprehensively analyzed rates of changes in antihypertensive drug prescription in CKD (add-on and withdrawal), the association of these changes with patient- and provider-related factors, and the short-term systolic BP trajectory in patients with and without an add-on of an antihypertensive drug over follow-up.

Methods

Data Source and Population

The CKD–Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (CKD-REIN) is a prospective cohort study conducted in 40 French nephrology clinics, nationally representative (geographically and by legal status). From 2013-2016, we included 3,033 patients with moderate-to-advanced CKD not transplanted nor on maintenance dialysis. The CKD-REIN cohort study's complete rationale, design, and methods are available elsewhere.18 The French National Institute of Health and Medical Research's institutional review board approved the protocol (reference: IRB00003888); the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03381950). All study participants were aged ≥18 years and provided informed consent.

We identified patients with a diagnosis of arterial hypertension in medical records (n = 2,605), a prescription of antihypertensive drugs (n = 2,822), or a systolic/diastolic BP ≥130/80 mm Hg at least twice (n = 2,036), ie, a total of 2,957 patients at baseline. After excluding patients with missing data for nephrologist identification (n = 2), BP at baseline (n = 14), or antihypertensive drug status over follow-up (n = 186), we studied 2,755 patients (Fig S1).

Explanatory Variables

Baseline and annual data collected from interviews, records, and self-administered questionnaires included sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, and laboratory data. Diabetes was defined by glucose-lowering drug prescription(s), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5%, fasting glucose ≥7 mmol/L, or nonfasting glucose ≥11 mmol/L. CV history at baseline included heart failure (HF), coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, and dysrhythmias. Spot or 24-hour urine tests, prescribed as routine care, were used to calculate sodium-creatinine ratios.19 Urinary albumin-creatinine ratios (ACR) were measured or estimated from protein-creatinine ratios.20 The glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated with the 2021 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.21 CKD is classified by eGFR (G1-G5, with cutoffs at 90, 60, 30, and 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) and ACR (A1-A3, with cutoffs at 30 and 300 mg/g). Height and weight were measured by nephrologists or outpatient nurses during a routine visit, and used for body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) calculation. Adherence to medications was assessed with the Girerd score,22 calculated with 6 items and described in 3 categories, good, moderate, and poor. Participants reported the number of visits to their primary care physician (PCP) and specialists in the year preceding enrollment through self-administered questionnaires.

Information on BP and Antihypertensive Drugs

Study protocol required BP to be measured at least twice, in sitting position, after a 5-minute rest; the average of these measurements was used in all analysis. These measurements were performed by nephrologists or outpatient nurses once a year by protocol or more frequently during routine visits. Participants were asked to bring all drug prescriptions (from any doctor) over the past 3 months to their inclusion visit and all prescriptions for the preceding year to each annual follow-up visit. Antihypertensive drugs were then coded according to the international Anatomic Therapeutic and Chemical thesaurus (Table S1) and analyzed at levels 3 (pharmacologic subgroup) and 4 (chemical subgroup) of the Anatomic Therapeutic and Chemical hierarchy.23

We evaluated changes in antihypertensive drug classes prescribed during follow-up: add-on, switch, and withdrawal. Patients were followed up until initiation of kidney replacement therapy (KRT), death before KRT, completion of 5 years of follow-up, loss to follow-up, or censoring on December 31, 2020.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics and antihypertensive drug classes were described overall and by subgroups at baseline (systolic BP, CKD G stage, and CKD A stage). All changes were considered to estimate overall rates of add-ons, withdrawals, and switches. All patients were considered at risk of any change and any add-on during their follow-up, only periods in which patients were prescribed at least one antihypertensive drug were considered for any withdrawal. For specific drug classes, periods when patients were not prescribed the drug were considered for add-on rate, and periods when patients were prescribed the drug were considered for withdrawal rate. Because few switches were identified during follow-up, we estimated class-specific rates only for add-ons or withdrawals. The first 3 changes in the number of classes during follow-up were depicted graphically with a Sankey plot.

We estimated crude and adjusted cause-specific hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of an antihypertensive drug class add-on or withdrawal (first event) associated with patient- and provider-related factors using hierarchical shared-frailty models. Models accounted for clustering at the nephrologist level through a lognormal random effect. Factors previously identified in the literature as risk factors for hypertension (eg, comorbid conditions) and factors describing provider or health care features (eg, number of medical visits) were modeled as fixed effects (details in Item S1: Supplementary Methods). We tested the interaction term between systolic BP and the number of antihypertensive drug classes, which was significant for add-on. Log-linearity and proportional hazard assumptions were checked graphically with Martingale and Schoenfeld residuals, respectively. Death and KRT initiation were competing risks.

To describe short-term trends in systolic BP, we performed linear mixed models with random intercept and slope for patients with and without add-on of an antihypertensive drug class. Fixed effects were time, add-on status, and the interaction between these 2. Time zero corresponds to the timing of add-on and 8.4 months from baseline (median time to first add-on) for patients with and without add-on, respectively. We performed multiple imputation of missing data with a multivariate normal model fitted using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method that takes a 2-level data structure into account (JOMO package for R software).24 We used Rubin and Schencker’s framework to combine estimates across 30 imputed datasets.25 As a sensitivity analysis, we added the urinary sodium-creatinine ratio (both in mmol/L) in patients with complete data (n = 1,975). Statistical significance was defined by P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Among 2,755 patients, median age was 69 years, 933 (34%) were women, and the mean eGFR was 33 mL/min/1.73 m2. At baseline 2,232 patients (81%) had BP ≥ 130/80, and 1,515 (55%) a mean BP ≥140/90 mm Hg. Two or more antihypertensive drug classes were prescribed to 2,066 (75%). Those with a lower systolic BP were younger; more highly educated; had less severe albuminuria; and had lower frequencies of CAD, HF, or cerebrovascular disease (Table 1). Most patients received care in clinics at university hospitals, especially patients in the lowest systolic BP group (Table S2). More than half the patients (55%) had seen a PCP at least 4 times in the year before study enrollment, 2,327 (97%) had seen the nephrologist at least once, and 1,692 (70%) a cardiologist or a diabetologist.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline, Overall and by Systolic Blood Pressure Level (mm Hg)

| Systolic Blood Pressure Levels Baseline Characteristics |

All (n = 2,755) | <120 (n = 282) | 120-129 (n = 415) | 130-139 (n = 615) | 140-159 (n = 946) | ≥ 160 (n = 497) | Missing Data N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 69 (61-77) | 65 (51-73) | 66 (56-72) | 68 (59-76) | 70 (64-77) | 71 (66-78) | 0 (0%) |

| Women, n (%) | 933 (34%) | 107 (38%) | 145 (35%) | 205 (33%) | 308 (33%) | 168 (34%) | 0 (0%) |

| Education (years), n (%) | 32 (1.2%) | ||||||

| <9 | 413 (15%) | 37 (13%) | 51 (12%) | 89 (15%) | 146 (16%) | 90 (18%) | |

| 9-11 | 1,356 (50%) | 125 (45%) | 184 (45%) | 291 (48%) | 493 (52%) | 263 (54%) | |

| ≥12 | 954 (35%) | 114 (42%) | 175 (43%) | 231 (37%) | 296 (32%) | 138 (28%) | |

| Adherencea | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| Good | 1,029 (37%) | 106 (38%) | 154 (37%) | 244 (40%) | 353 (37%) | 172 (35%) | |

| Moderate | 1,527 (55%) | 153 (54%) | 235 (57%) | 322 (52%) | 527 (56%) | 290 (58%) | |

| Poor | 199 (8%) | 23 (8%) | 26 (6%) | 49 (8%) | 66 (7%) | 35 (7%) | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean (SD) | 33 (12) | 34 (12) | 34 (12) | 33 (12) | 33 (12) | 32 (12) | 0 (0%) |

| Albumin-creatinine ratio (mg/g), median (IQR) | 122 (25-544) | 71 (16-402) | 81 (22-388) | 100 (23-390) | 134 (24-615) | 244 (39-824) | 397 (14%) |

| Medical history n (%) | |||||||

| Diabetes | 1,202 (44%) | 101 (36%) | 150 (36%) | 241 (39%) | 460 (49%) | 250 (51%) | 6 (0.2%) |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 1,466 (54%) | 152 (54%) | 201 (49%) | 305 (50%) | 522 (56%) | 286 (58%) | 34 (1.2%) |

| Coronary artery disease (CAD) | 680 (25%) | 75 (27%) | 97 (24%) | 130 (22%) | 251 (27%) | 127 (26%) | 51 (1.9%) |

| Heart failure (HF) | 368 (13%) | 65 (23%) | 46 (11%) | 82 (13%) | 119 (13%) | 56 (11%) | 6 (0.2%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) | 311 (12%) | 26 (9%) | 46 (11%) | 65 (11%) | 105 (11%) | 69 (14%) | 63 (2.3%) |

| Acute kidney injury | 593 (22%) | 66 (24%) | 90 (22%) | 125 (20%) | 199 (21%) | 113 (23%) | 32 (1.2%) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.8 (5.8) | 27.6 (5.9) | 28.1 (5.6) | 28.4 (5.6) | 29.5 (5.9) | 29.4 (6.0) | 57 (2.1%) |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 142 (20) | 112 (7) | 124 (3) | 134 (3) | 148 (6) | 172 (12) | 0 (0%) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg), mean (SD) | 78 (12) | 68 (9) | 74 (9) | 77 (9) | 79 (11) | 85 (13) | 1 (<0.1%) |

| Number of BP measurements over the follow-up, median (IQR) | 7 (5 - 11) | 7 (5 - 10) | 7 (4 - 10) | 8 (5 - 11) | 7 (5 - 10) | 8 (5 -11) | 0 (0%) |

| Time interval between BP measurements (mo), median (IQR) | 5.4 (3.2-7.1) | 5.8 (3.9-8.2) | 5.8 (3.5-8.3) | 5.7 (3.5-7.5) | 5.1 (3.0-6.9) | 4.8 (3.0-6.4) | 0 (0%) |

| Urinary sodium-creatinine ratio, median (IQR) | 12 (9-17) | 11 (8-15) | 11 (8-16) | 12 (8-16) | 12 (9-17) | 13 (10-18) | 780 (28%) |

| Number of drugs prescribed, median (IQR) | 8 (5-11) | 7.5 (5-10) | 7 (5-10) | 7 (5-10) | 8 (6-11) | 8 (6-11) | 0 (0%) |

| Number of antihypertensive drugs prescribed, median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Adherence to medications was assessed with the Girerd score, calculated with 6 items and described in 3 categories, good, moderate, and poor.22

Antihypertensive Drug Prescriptions at Baseline

The most frequently prescribed antihypertensive drug classes were RAS inhibitors (RASis) (2,133 [77%]), diuretics (1,531 [56%]), CCBs (1,308 [48%]), and β-blockers (1,170 [42%]) (Table S3). Amiloride, methyldopa, pyrimidine derivatives, and rauwolfia alkaloids (reserpine) were rarely or never described (≤1%). Overall, 257 antihypertensive drug regimens were observed at baseline (10 single class and 247 class combinations, Table S4). The top 5 prescriptions included RASi alone (405 [15%]) or in combination (1,735 [63%]), followed by diuretics + RASi (246 [9%]), diuretics + CCBs + RASi (241 [9%]), diuretics + β-blockers + RASi (229 [8%]), and diuretics + β-blockers + CCBs + RASi (226 [8%]). No other antihypertensive drug regimen was prescribed to more than 6% of patients.

Rates of Changes in Antihypertensive Drug-Class Prescriptions

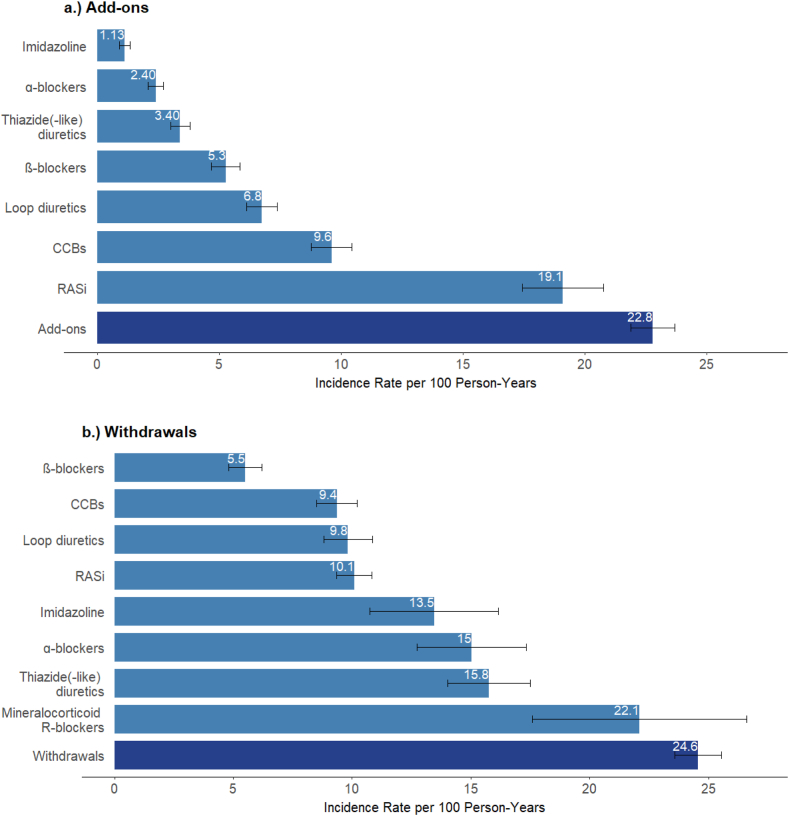

During a median 5-year follow-up (interquartile range [IQR], 4.6-5.2), we observed 2,411 drug-class add-ons, 2,463 withdrawals, and 391 switches. The number of add-ons and withdrawals was highest for RASi (507 and 725, respectively) and CCBs (514 and 449). The rate of any change of antihypertensive prescription was 50 per 100 person-years (PY) (Table S5). The rates of add-on and withdrawal of an antihypertensive drug class were nearly the same (23 and 25 per 100 PY, respectively); the switch rate was much lower at 3.90 per 100 PY. Add-on rates were highest for RASi (19 per 100 PY) and CCBs (9.6 per 100 PY), and withdrawal rates were highest for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) (22 per 100 PY) and thiazide diuretics (16 per 100 PY, Fig 1, Table S5).

Figure 1.

Rates of add-ons and withdrawals (with 95% confidence intervals) by antihypertensive drug class. Figure displays add-on and withdrawal rates for drug classes with at least 85 events. Rates for drug classes with fewer events, as well as number of events and persons at risk for all drug classes are shown in Supplementary Table 5.

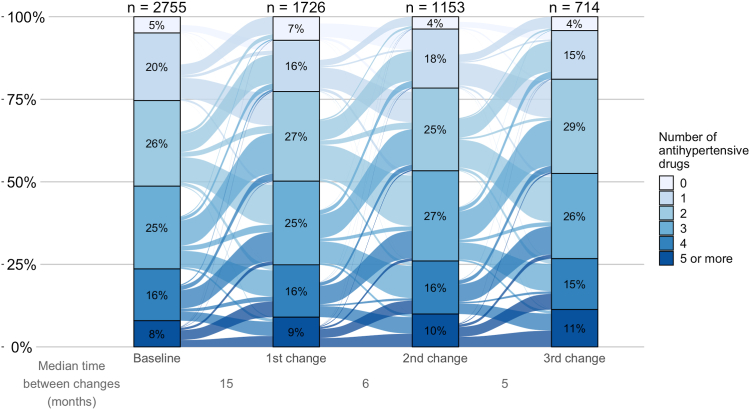

At the time of the add-on, the median number of antihypertensive drug classes prescribed was higher among patients who were added MRAs, α-blockers, or imidazoline (median of 3; IQR, 2-4, Table S6) than for patients who were added other classes (median of 2; IQR, 1-3). These patients were less often prescribed RAS inhibitors (59%-71% at the time of add-on of a drug class, RAS inhibitors excluded) compared with the overall sample (77% at baseline). The median number of antihypertensive drug classes prescribed at the time of prescription withdrawal was 5 (IQR, 4-5) for imidazoline, 4 (IQR, 3-5) for MRAs, and α-blockers, and 3 (IQR, 2-4) for other drug classes. Because almost the same proportion of patients had a drug class added as withdrawn during follow-up, the distribution of the number of antihypertensive drug classes prescribed remained virtually unchanged over time (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in the number of antihypertensive drugs prescribed during follow-up. In this Sankey plot, bars represent the distribution of the number of antihypertensive drug classes at baseline and at the first 3 change time points. X-axis depicts the median time to each prescription change (in months). Y-axis represents the percentage of patients with a given number of drug classes prescribed. Links from one bar to another are proportional to the flow rate of patients whose number of antihypertensive drug classes changed.

Factors Associated with Changes of Antihypertensive Drug Prescriptions

For patients prescribed up to 2 antihypertensive drug classes, the hazard of adding an antihypertensive drug class was higher at higher levels of baseline systolic BP, starting from values around 140 mm Hg (Table 2, Supplementary Table S7, and Fig S2). Inversely, the higher the baseline number of these classes, the lower the hazard of adding another. After adjusting for these and other clinical and health care-related characteristics, 3 groups of patients—older, with higher BMI, and with poor adherence—had a higher hazard of an add-on. Patients with more visits to the nephrologist or to another specialist and care in a private nonprofit nephrology facility versus a nonuniversity hospital also had a higher hazard of an add-on.

Table 2.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios For The Add-On and Withdrawal of an Antihypertensive Drug Class Associated with Patient- and Provider-Related Factors

| Factors | HR (95% CI) Adjusted Models |

|

|---|---|---|

| Add-onsa | Withdrawals | |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg, reference: 120 mm Hgb) | ||

| 110 mm Hg | 1.00 (0.80-1.25) | 1.13 (0.99-1.30) |

| 130 mm Hg | 1.03 (0.91-1.17) | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) |

| 140 mm Hg | 1.11 (0.97-1.28) | 0.91 (0.83-0.99) |

| 150 mm Hg | 1.21 (1.03-1.42)c | 0.90 (0.80-1.01) |

| Age (per 10-y increase) | 1.09 (1.01-1.17)c | 1.06 (0.99-1.14) |

| Men | 0.95 (0.81-1.12) | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) |

| Education (years, reference: ≥12 y) | ||

| 9-11 | 1.15 (0.90-1.46) | 1.23 (1.02-1.49)c |

| <9 | 1.08 (0.91-1.28) | 0.96 (0.82-1.13) |

| Adherence (reference: good) | ||

| Moderate | 1.13 (0.97-1.32) | 1.14 (0.98-1.34) |

| Poor | 1.35 (1.01-1.80)c | 0.95 (0.70-1.29) |

| Diabetes | 0.99 (0.83-1.19) | 0.92 (0.78-1.09) |

| eGFR (per decrease of 10 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) | 1.05 (0.98-1.12) |

| ACR (mg/g, per increase of 10%) | 1.01 (1.01-1.02)c | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) |

| BMI (per 2 kg/m2increase) | 1.04 (1.01-1.06)c | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 1.09 (0.92-1.30) | 1.19 (1.02-1.39)c |

| Number of antihypertensive drugs classes prescribed (per increase of 1 drug class) | 0.78 (0.72-0.84)c | 1.54 (1.45-1.64)c |

| Number of visits to the PCP (reference: 0) | ||

| 1 or 2 | 1.04 (0.93-1.15) | 1.10 (1.00-1.22)c |

| 3 or 4 | 1.07 (0.87-1.31) | 1.21 (1.01-1.46)c |

| >4 | 1.11 (0.82-1.51) | 1.34 (1.03-1.74)c |

| Number of visits to nephrologist (reference: 0) | ||

| 1 or 2 | 1.15 (1.02-1.30)c | 1.16 (1.04-1.30)c |

| 3 or 4 | 1.32 (1.04-1.68)c | 1.35 (1.08-1.69)c |

| >4 | 1.52 (1.06-2.18)c | 1.57 (1.12-2.19)c |

| Number of visits to specialists in cardiology or diabetes (reference: 0) | ||

| 1 or 2 | 1.25 (1.08-1.45)c | 1.01 (0.88-1.16) |

| 3 or 4 | 1.57 (1.17-2.11)c | 1.02 (0.77-1.34) |

| >4 | 1.97 (1.27-3.07)c | 1.02 (0.68-1.54) |

| Legal status of the nephrology facility (reference: nonuniversity hospital) | ||

| University hospital | 1.01 (0.84-1.22) | 0.93 (0.74-1.17) |

| Private for-profit clinic | 0.79 (0.61-1.02) | 0.74 (0.53-1.04) |

| Private nonprofit clinic | 1.62 (1.20-2.19)c | 0.91 (0.58-1.44) |

Note: For the adjusted model of withdrawals and of add-ons, the median frailty variance was 0.12 (95% CI 0.08-0.16, P < 0.001) and 0.00 (95% CI -0.04 to 0.04, P > 0.05), respectively.

Abbreviations: ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratios; PCP, primary care physician.

In the add-on model, the interaction term between systolic BP and the number of antihypertensive drug classes prescribed was significant. The HRs displayed for systolic BP were calculated for patients with 2 antihypertensive drug classes prescribed, whereas the that for the number of antihypertensive drug classes was calculated for patients with a systolic BP of 140 mm Hg (both medians values for these characteristics in the overall population).

HRs of add-ons or withdrawals associated with systolic BP were derived with spline functions (Supplementary Figure S2). Comparisons against systolic BP at 120 mm Hg are based on exact systolic BP values (ie, 110, 130, 140, and 150 mm Hg).

Indicates 95% confidence intervals excluding 1 (one).

After multivariable adjustment, the hazard of having an antihypertensive drug class withdrawn was higher among patients with any of the following: systolic BP <110 mm Hg, more antihypertensive drug classes at baseline, a CV history, more frequent visits to their PCP or nephrologist, or an education level of 9-11 versus ≥12 years. The hazard of withdrawal also varied significantly according to the patient's nephrologist (median frailty variance, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.08-0.16; P < 0.001).

The sensitivity analysis yielded associations similar to the main analysis (Supplementary Table S8) with no statistically significant association of the urinary sodium-creatinine ratio with add-on or withdrawal.

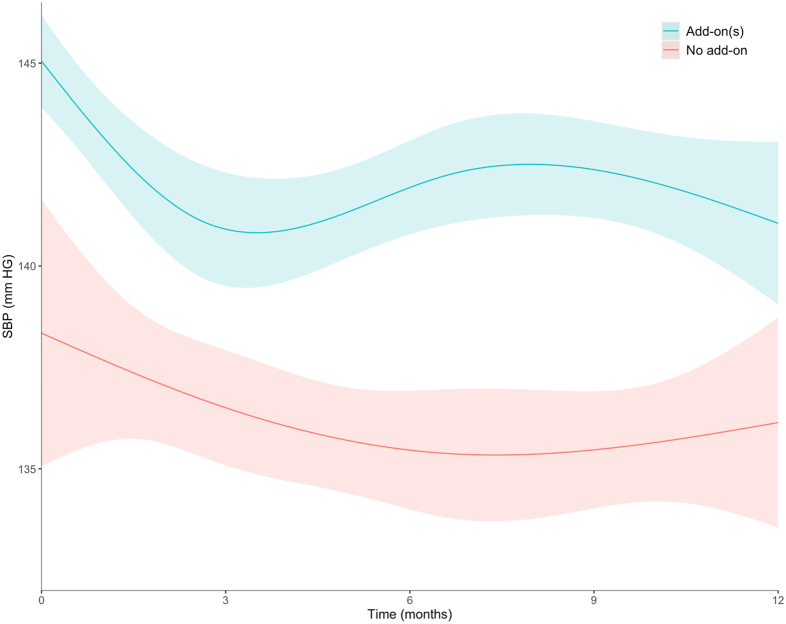

Short-term Changes in Systolic BP Following Add-on of an Antihypertensive Drug Class

In patients with add-on of an antihypertensive drug class, mean systolic BP at start was 145 ± 1.1 mm Hg and was reduced by 4.1 mm Hg (95% CI, 2.1-6.2, Fig 3) in the first 3 months. After the third month, systolic BP increased slightly by 1.6 mm Hg (95% CI, −0.8 to 3.9), but without reaching its initial level up to 1 year after. In patients with no add-on, mean systolic BP was lower, 138 ± 3.3 mm Hg, and tended to decline smoothly, by 2.2 mm Hg (95% CI, −3.5 to 7.9), over the considered 1-year period.

Figure 3.

One-year systolic BP trends in patients with and without an add-on of an antihypertensive drug. In patients with add-on of an antihypertensive drug class, time zero corresponds to timing of add-on. In patients without add-on, time zero corresponds to 8.4 months from baseline (median time of the first add-on in patients who had it). Abbreviation: SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Discussion

In a large cohort of patients with moderate-to-severe CKD receiving care from a nephrologist, we identified substantial heterogeneity in antihypertensive prescriptions. Contrary to our initial hypothesis to explain the poor BP control in this population, we observed dynamic changes in these prescriptions over follow-up. The overall 20 per 100 patient-year rates for both add-ons and withdrawals nonetheless concealed disparities across drug classes, potentially informative about prescriber preferences and patient tolerance. We identified CV risk factors and comorbid conditions specifically associated with the add-on or withdrawal of drug classes. The higher hazards of add-on or withdrawal associated with more frequent physician visits seemed to vary by specialty. Importantly, our analysis showed that add-on of an antihypertensive drug class was associated with subsequent decrease in systolic BP level in CKD in real-world, yet this decrease was modest and poorly sustained in time.

We identified 257 distinct antihypertensive drug regimens at baseline (based on the type and number of drug classes). Over the study period, we observed that antihypertensive drug prescriptions were dynamic, with high rates of both drug class add-ons and withdrawals of 23 and 25 per 100 PY, respectively. This dynamic nonetheless resulted in a virtually stable distribution of the number of classes prescribed, but rates varied substantially by drug class. Our results indicate, for example, high rates of RASi prescription in patients not yet under RAS blockade. It is noteworthy that the MRA prescription rate was one-quarter that of centrally acting drugs (α-adrenergic antagonists and imidazoline). Despite MRA's well-established benefits in resistant hypertension and HF management,26,27 concerns about its life-threatening risks in CKD, including hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury, have precluded its widespread use in CKD patients.28

After adjustment for clinical and health care-related characteristics, patients with older age and higher BMI had higher rates of an antihypertensive drug add-on, consistent with the high prevalence of treatment-resistant hypertension in these populations.29 Moderate and poor adherence to drug therapy were common (55% and 7% of patients, respectively) and showed a graded association with a higher hazard of add-ons. This finding points to the need to evaluate adherence systematically before intensifying therapy. We also found nephrology care in private nonprofit clinics to be associated with greater likely of an add-on class compared with other types of facilities (public university or nonuniversity hospitals and private for-profit clinics). It is not clear whether this finding is because of specific care protocols or patient profiles because, in France, these clinics are often intended to care for patients with less complex CKD. On the other hand, the adjusted hazard of withdrawing an antihypertensive drug class was higher in patients with than without a history of CV disease. Deprescribing is part of the continuum of good prescription practices and may be particularly important among patients with multiple comorbid conditions and polypharmacy.30

Changes in these prescriptions were associated with more frequent medical visits in the preceding year. Except for nephrologists (similarly associated with add-ons and withdrawals), the associated physician specialties differed. The rate of add-ons was higher in patients seeing specialists (in cardiology, endocrinology, and diabetes) more often, whereas the rate of withdrawals was more likely in patients seeing their PCP more often. PCPs remain at the frontline of CKD management and may have to deal with medication-related complaints more frequently. With enhanced diagnosis and awareness of CKD, the number of patients with CKD has increased dramatically over the past 2 decades and demonstrated the need to develop optimal models of nephrology referral and coordinated care.31

Of note, the magnitude of decline in systolic BP decline (4.1 mm Hg) at 3 months in patients with an add-on was similar to that reported in a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of the effects of antihypertensive drugs on long-term BP at 6 months.32 However, systolic BP did not reach optimal levels and tended to rebound after 3 months from add-on, consistent with the rates of withdrawal in our study (as much that of add-on). This finding underlines the difficulty of achieving BP control in CKD in the real-world setting and calls for interventions to manage adverse drug reactions leading to drug withdrawal.

Our study has several strengths. It is based on a large number of patients with confirmed CKD diagnoses and hypertension recruited from a representative sample of nephrology outpatient facilities. Our detailed survey of prescribed drugs constitutes a unique aspect of this study that allowed us to identify all prescription changes over a 5-year follow-up and provide information for each antihypertensive drug class.

Our study also has several limitations. One-quarter of prescription or deprescription dates were imputed. Dosing and prescriber specialty could not be assessed. Lack of information about individual BP goals precluded formal assessment of therapeutic inertia. Finally, the study period (2013-2020) does not allow us to assess the adherence to the 2021 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline update for antihypertensive management and the impact of the introduction of new drugs. Our findings may, however, provide a basis for a future analysis of the trends in clinical practices and be useful for future clinical trials.

In conclusion, this study showed substantial heterogeneity and changes in antihypertensive prescription practices among patients with CKD, probably reflecting clinician preferences and the decreased tolerability of some drug classes. Our findings further suggest that specialists and PCPs have different roles in prescribing and deprescribing drugs for patients with CKD, which underlines the importance of coordinated care. The reduction in systolic BP following add-on of an antihypertensive drug class in the real-world seemed, however, modest, and not long-lasting, consistent with the high rates of withdrawal and frequent poor self-reported adherence in this population.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Margaux Costes-Albrespic, MPH, Sophie Liabeuf, PhD, PharmD, Solène Laville, PhD, PharmD, Christian Jacquelinet, PhD, MD, Christian Combe, PhD, MD, Denis Fouque, PhD, MD, Maurice Laville, MD, Luc Frimat, PhD, MD, Roberto Pecoits-Filho, PhD, MD, FACP, FASN, Oriane Lambert, MSc, Ziad A. Massy, PhD, MD, FERA, Bénédicte Sautenet, PhD, MD, Natalia Alencar de Pinho, PhD, and the CKD-REIN study group

CKD-REIN study group

Natalia Alencar de Pinho, Christian Combe, Denis Fouque, Luc Frimat, Aghilès Hamroun, Christian Jacquelinet, Maurice Laville, Sophie Liabeuf, Ziad A. Massy, Abdou Omorou, Christophe Pascal, Roberto Pecoits-Filho, Bénédicte Stengel, Céline Lange, Oriane Lambert, Marie Metzger∗

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: NAP, BSau; data acquisition: CJ, CC, DF, ML, LF, RPF, OL, ZAM; data analysis/interpretation: MCA, SLia, SLav, CJ, CC, DF, ML, LF, RPF, OL, ZAM, BSau, NAP; statistical analysis: MCA; supervision or mentorship: NAP, BSau, SLia, ZAM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated, and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Support

CKD-REIN is funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche through the 2010 “Cohortes-Investissements d’Avenir” program (ANR-IA-COH-2012/3731) and by the 2010 national Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique. CKD-REIN is also supported through a public-private partnership with Fresenius Medical Care and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) since 2012 and Vifor France since 2018, Sanofi-Genzyme from 2012 to 2015, Baxter and Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret (MSD France) from 2012 to 2017, Amgen from 2012 to 2020, Lilly France from 2013 to 2018, Otsuka Pharmaceutical from 2015 to 2020, AstraZeneca from 2018 to 2021 and Boehringer Ingelheim France since 2022. Inserm Transfert set up and has managed this partnership since 2011.

Financial Disclosure

MCA, SLia, SLav, CJ, CC, DF, ML, OL, LF, and BSau declare no conflict of interest. NAP coordinates the CKD-REIN cohort study, and received funding as indicated below. RPF received honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer, Lilly, Akebia, Bayer, GSK, Novo Nordisk, George Clinical and Fresenius Medical Care, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development. ZAM reports having received grants for CKD-REIN and other research projects from Amgen, Baxter, Fresenius Medical Care, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret, Sanofi- Genzyme, Lilly, Otsuka, AstraZeneca, Vifor and the French government, as well as fees and grants to charities from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the CKD-REIN study coordination staff for their efforts in setting up the CKD-REIN cohort, all the clinical research associates, as well as the CKD-REIN clinical sites and investigators (indicated in Supp Information). We thank Jo Ann Cahn for editing the English version.

Data Sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request by contacting the CKD-REIN study coordination staff at ckdrein@inserm.fr.

Peer Review

Received November 17, 2023. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted June 18, 2024 in revised form.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Figure S1: (A) Flow chart of selected patients at baseline in the CKD-REIN cohort and (B) Venn diagram of hypertension definition.

Figure S2: Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of natural cubic splines of the adjusted association between systolic blood pressure and (A) add-on and (B) withdrawal hazard.

Item S1: Supplementary methods.

Item S2: CKD-REIN clinical sites and investigators.

Table S1: Anatomical Therapeutic and Chemical (ATC) Codes of Antihypertensive Drugs.

Table S2: Nephrology Facility Type and Number of Medical Visits in the Year Preceding Study Enrollment, Overall and by Systolic Blood Pressure Level (mm Hg).

Table S3: Antihypertensive Drug Classes Prescribed at Baseline by (A) CKD G Stage and (B) CKD A Stage.

Table S4: Antihypertensive Regimens Prescribed at Baseline.

Table S5: Number of Events, Number of Patients at Risk, and Rates (95% confidence intervals) of (A) Changes in Antihypertensive Drug Class Prescription Overall, (B) Add-ons, and (C) Withdrawals by Drug Class.

Table S6: Antihypertensive Drug Classes Prescribed at the Time of Changes Overall and by Antihypertensive Drug Classes for (A) Add-ons and (B) Withdrawals.

Table S7: Crude Hazard Ratios of Add-on and Withdrawal of an Antihypertensive Drug Class Associated with Patient- and Provider-related Factors.

Table S8: Sensitivity analysis: Crude and Adjusted Hazard Ratios of Add-ons and Withdrawals of Antihypertensive Drug Classes Associated with Patient- and Provider-related Factors with Complete Data for the Sodium-Creatinine Ratio (n = 1,975).

Contributor Information

Natalia Alencar de Pinho, Email: natalia.alencar-de-pinho@inserm.fr.

CKD-REIN study group:

Natalia Alencar de Pinho, Christian Combe, Denis Fouque, Luc Frimat, Aghilès Hamroun, Christian Jacquelinet, Maurice Laville, Sophie Liabeuf, Ziad A. Massy, Abdou Omorou, Christophe Pascal, Roberto Pecoits-Filho, Bénédicte Stengel, Céline Lange, Oriane Lambert, and Marie Metzger

Supplementary Material

Figures S1-S2; Items S1-S2; Tables S1-S8.

References

- 1.Mills K.T., Bundy J.D., Kelly T.N., et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muntner P., Anderson A., Charleston J., et al. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in adults With CKD: Results From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):441–451. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ku E., Lee B.J., Wei J., Weir M.R. Hypertension in CKD: core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(1):120–131. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The SPRINT Research Group A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra R., Nguyen H.A., Benavente O., et al. Association between more intensive vs less intensive blood pressure lowering and risk of mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1498. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie X., Atkins E., Lv J., et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):435–443. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Li J.J., Wang A.J., et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure control on mortality and cardiorenal function in chronic kidney disease patients. Ren Fail. 2021;43(1):811–820. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2021.1920427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelton P.K., Carey R.M., Aronow W.S., et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunstro M., Muiesan M.L., Tsioufis K., et al. The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2023;41(1) doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000003480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung A.K., Chang T.I., Cushman W.C., et al. KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2021;99(3):S1–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alencar de Pinho N., Levin A., Fukagawa M., et al. Considerable international variation exists in blood pressure control and antihypertensive prescription patterns in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2019;96(4):983–994. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An J., Luong T., Qian L., et al. Treatment patterns and blood pressure control with initiation of combination versus monotherapy antihypertensive regimens. Hypertension. 2021;77(1):103–113. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spirk D., Noll S., Burnier M., Rimoldi S., Noll G., Sudano I. Effect of home blood pressure monitoring on patient’s awareness and goal attainment under antihypertensive therapy: The Factors Influencing Results in Anti-HypertenSive Treatment (FIRST) Study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43(3):979–986. doi: 10.1159/000490687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skoglund P.H., Svensson P., Asp J., et al. Amlodipine+Benazepril is superior to Hydrochlorothiazide+Benazepril irrespective of baseline pulse pressure: subanalysis of the ACCOMPLISH Trial. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17(2):141–146. doi: 10.1111/jch.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jr J.T.W., Probstfield J.L., Cushman W.C. ALLHAT findings revisited in the context of subsequent analyses, other trials, and meta-analyses. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):832–842. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faucon A.L., Fu E.L., Stengel B., Mazhar F., Evans M., Carrero J.J. A nationwide cohort study comparing the effectiveness of diuretics and calcium channel blockers on top of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on chronic kidney disease progression and mortality. Kidney Int. 2023;104(3):542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonelli M., Wiebe N., Manns B.J., et al. Comparison of the complexity of patients seen by different medical subspecialists in a universal health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stengel B., Combe C., Jacquelinet C., et al. The French Chronic Kidney Disease-Renal Epidemiology and Information Network (CKD-REIN) cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(8):1500–1507. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flack J.M., Grimm R.H., Staffileno B.A., et al. New salt-sensitivity metrics: variability-adjusted blood pressure change and the urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(1):10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumida K., Nadkarni G.N., Grams M.E., et al. Conversion of urine protein–creatinine ratio or urine dipstick protein to urine albumin–creatinine ratio for use in chronic kidney disease screening and prognosis: an individual participant–based meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(6):426–435. doi: 10.7326/M20-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inker L.A., Eneanya N.D., Coresh J., et al. New creatinine- and cystatin c–based equations to estimate gfr without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737–1749. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girerd X., Radauceanu A., Achard J.M., et al. [Evaluation of patient compliance among hypertensive patients treated by specialists] Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2001;94(8):839–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2023. Published online. Oslo, Norway 2022. https://atcddd.fhi.no/filearchive/publications/1_2024_guidelines__final_web.pdf

- 24.Quartagno M., Grund S., Carpenter J. jomo: A flexible package for two-level joint modelling multiple imputation. R J. 2019;11(2):205. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin D.B., Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-are databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med. 1991;10(4):585–598. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams B., MacDonald T.M., Morant S., et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;386(10008):2059–2068. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eschalier R., McMurray J.J.V., Swedberg K., et al. Safety and efficacy of eplerenone in patients at high risk for hyperkalemia and/or worsening renal function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(17):1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossignol P., Massy Z.A., Azizi M., et al. The double challenge of resistant hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1588–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00418-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calhoun D.A., Jones D., Textor S., et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. Circulation. 2008;117(25):e510–e526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnaswami A., Steinman M.A., Goyal P., et al. Deprescribing in older adults With cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(20):2584–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckardt K.U., Delgado C., Heerspink H.J.L., et al. Trends and perspectives for improving quality of chronic kidney disease care: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2023;104(5):888–903. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canoy D., Copland E., Nazarzadeh M., et al. Antihypertensive drug effects on long-term blood pressure: an individual-level data meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Heart. 2022;108(16):1281–1289. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2021-320171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1-S2; Items S1-S2; Tables S1-S8.