Abstract

Introduction

Hyporesponsiveness to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) in patients with anaemia of chronic kidney disease may lead to increased ESA doses to achieve target haemoglobin levels; however, elevated doses may be associated with increased mortality. Furthermore, patients with hyporesponsiveness to ESAs have poorer clinical outcomes than those who respond well to ESAs. Incidence and clinical characteristics of patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness were explored in a real-world setting.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of electronic medical records of adults with stage 5 chronic kidney disease receiving renal replacement therapy and ESA treatment, from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2021. The primary objective was ESA hyporesponsiveness rate/1000 days, with a hyporesponsive event defined as ESA use at an elevated dose, according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) criteria. Other hyporesponsiveness definitions applied were erythropoietin resistance index-defined ESA hyporesponsiveness (ERI) Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) and a clinical practicality algorithm.

Results

In total, 85,259 patients were included in the analysis; 59.9% were male, median (interquartile range) ESA starting dose was 733.3 (400.0, 1200.0) IU/week and follow-up duration was 2.2 (1.0, 4.2) years. Incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness varied when applying different definitions; NICE 0.05/1000 days (5.2% of patients), ERI 0.40/1000 days (40.7%), KDIGO 0.15/1000 days (15.4%), and clinical practicality algorithm 0.48/1000 days (47.9%). ESA doses remained higher in hyporesponsive versus responsive patients, yet haemoglobin levels were similar between groups.

Conclusion

The results from this study, which applied multiple hyporesponsiveness definitions to a large, geographically diverse population of patients with anaemia of CKD, showed variation in ESA hyporesponsiveness incidence rates depending on definitions used and higher ESA doses in hyporesponsive versus responsive patients. These results underscore the need for individualised clinical assessment and thorough evaluation when considering ESA dose adjustments to reach haemoglobin targets.

Graphical abstract available for this article.

Trial Registration

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-03015-4.

Keywords: Anaemia, CKD, Dialysis, Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, Hyporesponsiveness

Plain Language Summary

Some people living with kidney disease may also have anaemia (low numbers of blood cells). This can increase their risk of heart disease and reduce their quality of life. Treatments for anaemia in people living with kidney disease include iron supplements and drugs that stimulate the production of red blood cells, known as erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. However, some people have weak responses to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and high doses can cause side effects. We looked at how the percentage of people with weak responses to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents varied when using different criteria to identify them. We also looked at the clinical characteristics of people who experienced a weak response after 1 year and those who did not. To do this, we reviewed medical records from people treated at specialist kidney care centres across 24 countries from Europe and South Africa. We included medical records between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021. Depending on what criteria we used, the percentage of people living with kidney disease and anaemia who were identified as having weak responses to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents varied greatly, from 5.2% to 47.9%. People living with kidney disease and anaemia who have weak responses to treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents need adjustments to their care to address this. However, our research shows that the different criteria used to identify these patients can affect how many are identified, and may affect their care. Therefore, all patients with kidney disease and anaemia should be carefully monitored.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-03015-4.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Patients with anaemia of chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are hyporesponsive to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) have poorer clinical outcomes than those who respond well to ESA therapy. |

| There are a number of definitions for ESA hyporesponsiveness used in the literature. |

| The present study explored the real-world incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness using multiple definitions applied to a large, geographically diverse patient population and described their clinical characteristics. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness varied from 5.2% to 47.6%, depending on the definition used; however, higher ESA doses were seen in hyporesponsive versus responsive patients, despite similar haemoglobin levels. |

| The variation in incidence rates when applying different definitions of ESA and apparent residual persistent hyporesponsiveness highlight the importance of careful individual patient assessment should ESA dose increases be required. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.27055147.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive condition [1], estimated to affect around 697 million people worldwide as of 2019 [2]. Anaemia is a common complication of CKD, which increases in severity and prevalence as glomerular filtration rate declines [3]. Anaemia is also associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, CKD progression, mortality [4], and a negative impact on quality of life [5].

Clinical management of patients with anaemia of CKD typically comprises iron supplementation and treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) [6, 7]. However, these treatments have limitations [8]. Oral iron often leads to gastrointestinal side effects, resulting in reduced tolerability and poor adherence [9, 10], and, in those with CKD, it is poorly absorbed in the gut as a result of elevated hepcidin levels [11]. While intravenous (IV) iron has greater efficacy than oral iron [12], it can also further increase hepcidin levels and is associated with an increased risk of hypotension, headaches, hypersensitivity reactions, and infections [8, 13, 14]. ESAs are a key component of anaemia treatment in patients with CKD [6, 15]; however, increasing the ESA dose with the aim of reaching the target haemoglobin (Hb) level may raise the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [16, 17].

Hyporesponsiveness to ESAs is associated with poorer clinical outcomes compared with those who respond well to ESA therapy [18, 19]. There are various definitions of ESA hyporesponsiveness [6, 7, 20, 21], and the reported prevalence varies according to the criteria applied [22–24]. The present study aimed to identify the incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness using varied definitions in patients receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT) in a real-life clinical setting across a large, geographically diverse patient population and explore differences in clinical characteristics between ESA-hyporesponsive and ESA-responsive patients.

Methods

Study Design

This observational, retrospective, secondary database analysis (NCT05530291) was based on electronic medical records from the Fresenius Medical Care (FME) database, EuCliD, a health information system used by FME Nephrocare dialysis clinics worldwide. EuCliD is a multilingual database that serves more than 100,000 patients treated in FME clinics, with 126 million dialysis sessions recorded in the database. Medical data are collected during regular clinical practice and are stored and managed centrally. The development, structure, and purpose of the EuCliD database have been described in detail elsewhere [25].

The study population comprised adults ≥ 18 years of age with stage 5 CKD who were receiving chronic maintenance extracorporeal RRT and were treated with ESA between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021 in Nephrocare dialysis centres across 24 countries (11 from Western Europe, 12 from Eastern Europe, and South Africa). Eligible patients were required to have a known ESA administration route; a documented Hb value at index date (or within 20 days) and availability of at least one Hb value post index date; at least one body weight available; and have relevant data for the 30 days prior to the index (defined below). Patients receiving methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta were not included in the analysis, as these types of ESA are not included in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) definition of hyporesponsiveness. Patients who were ESA-naïve or ESA-experienced were both eligible for inclusion. Key exclusion criteria were evidence of hereditary haemolytic anaemia (defined by the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10 code D58.9), or a transplant within 6 months prior to the ESA initiation date.

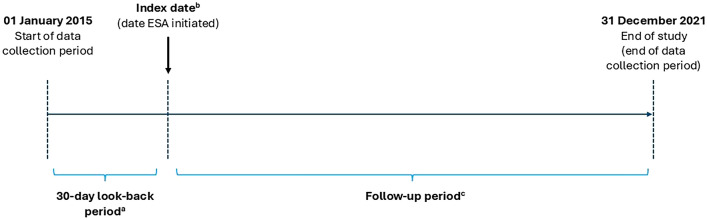

The index date was defined as the first treatment date with ESA within the study period (Fig. 1). The ESA hyporesponsiveness date, or first hyporesponsive event experienced by a patient within the study period, was the first occurrence of ESA use at the elevated dosing level defined according to NICE dosing criteria for hyporesponsiveness [7]: epoetin alfa ≥ 300 IU/kg/week subcutaneous (SC), or ≥ 450 IU/kg/week IV, or darbepoetin ≥ 1.5 μg/kg/week. For ESA dose calculations, the documented ESA dose was summed for each patient using the patient’s body weight measurement taken closest to the week of the start date and grouped by 7-day weekly intervals from the ESA initiation date. For darbepoetin, equivalent IU doses were calculated from µg (value in µg × 220) [26]. ESA hyporesponsiveness was assessed in this study with the assumption that treating physicians addressed intercurrent illness or chronic blood loss in the usual clinical care. The individual target Hb values used to adjust ESA doses were determined by the treating physician. Patients were followed from the index date to the point of experiencing an open event that resulted in censoring (death, transplantation, change in dialysis centre, or loss to follow-up), or reaching the study end.

Fig. 1.

Study design. aThe date of initiation of RRT was available for all patients included in the analysis in case there was a need for distinction between incident/non-incident patients. bDefined as the first ESA treatment date within the study period; patients with no relevant information on the ESA start date in the database were excluded from the analysis. cEnd of follow-up was earliest date of death, transplantation, dialysis centre change (i.e. moving outside of an FMW facility or an FME facility not using the EuCliD database), loss to follow-up, or end of study. ESA erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, RRT renal replacement therapy

Ethics

All data were pseudonymised and all patients provided written informed consent for access and secondary use of their pseudonymised clinical data for research purposes. According to the National Institutes of Health definition of human subject research, this study falls under the exempt human subjects research category [27].

Outcomes

The primary objective of this analysis was to describe the incidence rate of ESA hyporesponsiveness per 1000 days, defined according to NICE dosing criteria for hyporesponsiveness in the overall study population. ESA hyporesponsiveness according to the erythropoietin resistance index (ERI) [21] was also evaluated as an exploratory endpoint. Secondary objectives included evaluating the incidence rates of ESA hyporesponsiveness according to definitions (described below) from the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines [6] and a previously proposed clinical practicality algorithm (CPA) [20]; to evaluate ESA dose and Hb level patterns in patients who were ESA hyporesponsive or responsive (NICE-defined); to explore index date demographics and clinical characteristics for patients who became ESA hyporesponsive (defined according to NICE dosing criteria for hyporesponsiveness) or those who did not within 1 year; and to describe the proportion of patients experiencing isolated, intermittent, or chronic ESA hyporesponsiveness (defined below) after initiating ESA.

Defining ESA Hyporesponsiveness

In this analysis, in addition to the evaluation of NICE dosing criteria for hyporesponsiveness (epoetin alfa ≥ 300 IU/kg/week SC or ≥ 450 IU/kg/week IV, or darbepoetin ≥ 1.5 μg/kg/week; primary objective), patients were also evaluated using other definitions of hyporesponsiveness, including the ERI [21], the KDIGO guidelines [6], and the CPA [20]. The ERI is calculated as (ESA/weight)/Hb based on weekly averages [21]. The KDIGO guidelines criteria define a patient as ESA hyporesponsive if an increase in Hb level from baseline is not observed after the first month of ESA treatment with appropriate weight-based dosing [6]. The CPA used in the present study defined hyporesponsiveness as a patient requiring an ESA dose greater than the dosage administered to 90% of patients in that patient’s country.

To describe the proportion of the population with isolated, intermittent, or chronic hyporesponsiveness, NICE dosing criteria were used. Patients with up to two consecutive hyporesponsive months with no additional hyporesponsive months during the study period were classified as isolated hyporesponders, those with < 75% of the study period with hyporesponsive months were considered intermittent hyporesponders, and those with ≥ 75% of the study period with hyporesponsive months were considered chronic hyporesponders.

Statistical Analyses

No formal sample size estimation was performed. However, the number of patients receiving RRT who were treated with an ESA in the EuCliD database between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021 was expected to be > 50,000, with up to 30% anticipated to be hyporesponsive.

As a result of the exploratory nature of the analysis, no formal hypothesis was tested, and data were analysed using descriptive statistics (see Supplementary Methods in the Supplementary Material).

Results

Patient Disposition

Between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021, 380,675 patients with a diagnosis of CKD were identified, of whom 85,259 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis (Supplementary Material, Table S1). The greatest proportion of the study population was from Eastern European countries (n = 53,193; 62.4%), followed by Western European countries (n = 31,609; 37.1%), and South Africa (n = 457; 0.5%) (Supplementary Material, Table S2). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 2.2 (1.0, 4.2) years, and reasons for the end of patient follow-up were death (44.5%), end of study (26.3%), dialysis centre change (13.8%), transplantation (10.8%), other (3.2%), and loss to follow-up (1.5%).

Patient Characteristics

Baseline characteristics at index date for the overall population are presented in Table 1. Overall, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 63.8 (15.0) years, 59.9% of patients were male, and the mean (SD) body weight was 72.1 (16.9) kg. At index date, the median (IQR) levels for Hb and ferritin were 10.4 (9.4, 11.3) g/dL and 358.8 (181.2, 641.7) µg/L, respectively; the mean (SD) transferrin saturation (TSAT) was 25.2% (13.7%) (Table 1). Haemodiafiltration (HDF) was the renal replacement method for 38.4% of patients and 60.3% received haemodialysis. Arteriovenous fistula was the access method used for haemodialysis in 55.5% of patients, while 42.4% of patients had a central catheter.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics at index date (overall population)

| Characteristics | Overall, N = 85,259 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | n = 85,259 |

| Mean ± SD | 63.8 ± 15.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 66.0 (55.0, 75.0) |

| Age category, n (%) | |

| ≤ 65 years | 42,401 (49.7) |

| > 65 years | 42,858 (50.3) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 51,043 (59.9) |

| Body weight, kg | n = 84,811 |

| Mean ± SD | 72.1 ± 16.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 70.3 (60.0, 82.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | n = 76,506 |

| Mean ± SD | 26.9 ± 6.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 26.0 (22.8, 30.1) |

| Hb, g/dLa | n = 85,146 |

| Mean ± SD | 10.3 ± 1.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 10.4 (9.4, 11.3) |

| Ferritin, µg/La | n = 61,395 |

| Mean ± SD | 488.9 ± 458.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 358.8 (181.2, 641.7) |

| Transferrin, mg/dLa | n = 29,403 |

| Mean ± SD | 181.3 ± 43.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 177.0 (152.0, 204.0) |

| TSAT, %a | n = 49,279 |

| Mean ± SD | 25.2 ± 13.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 22.6 (16.0, 31.0) |

| Serum iron, µg/dLa | n = 55,275 |

| Mean ± SD | 58.9 ± 29.5 |

| Median (IQR) | 54.0 (39.0, 72.2) |

| TIBC, mg/dLa | n = 29,403 |

| Mean ± SD | 226.7 ± 54.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 221.3 (190.0, 255.0) |

| PTH, ng/La | n = 56,658 |

| Mean ± SD | 352.9 ± 330.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 258.0 (140.0, 449.3) |

| CRP, mg/dLa | n = 53,401 |

| Mean ± SD | 19.9 ± 36.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 6.6 (2.3, 19.3) |

| Albumin, g/dLa | n = 69,584 |

| Mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| Median (IQR) | 3.8 (3.5, 4.1) |

| Additional anaemia treatment, n (%)b | 59,629 (69.9) |

| IV iron, n (%) | 58,560 (68.7) |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 3760 (4.4) |

| Dialysis efficiency, Kt/V | n = 81,439 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.6 (0.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) |

| Dialysis type, n (%) | |

| Haemodialysis | 51,382 (60.3) |

| HDF | 32,701 (38.4) |

| PD | 926 (1.1) |

| Other | 250 (0.3) |

| Vascular access for dialysis, n (%) | |

| AVF | 45,934 (55.5) |

| AVG | 1721 (2.1) |

| Catheter | 35,093 (42.4) |

| Missing/unknown | 2511 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 12,214 (14.3) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 13,626 (16.0) |

| Hypertension | 52,165 (61.2) |

| Heart failure | 11,282 (13.2) |

| Drugs acting on RAAS, n (%) | 21,579 (25.3) |

AVF arteriovenous fistula, AVG arteriovenous graft, BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CRP C-reactive protein, ESA erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, Hb haemoglobin, HDF haemodiafiltration, IQR interquartile range, IV intravenous, NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, PD peritoneal dialysis, PTH parathyroid hormone, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SD standard deviation, TIBC total iron binding capacity, TSAT transferrin saturation

aAt index date (date of ESA initiation)

bDefined as receiving oral or IV iron and blood transfusions in addition to ESA treatment; if the patient received only ESA treatment, they were classed as having received no further anaemia treatment

Treatment at Index Date

In the overall patient population (n = 85,259), the median (IQR) ESA starting dose at index date was 733.3 (400.0, 1200.0) IU per week. A higher proportion of patients received epoetin alfa (60.2%) than darbepoetin (39.8%), with equal proportions having either IV or SC administration. At index date, additional (non-ESA) treatment for anaemia was administered to 69.9% of patients, including IV iron in 68.7% of patients and blood transfusions in 4.4% of patients.

Primary Endpoint

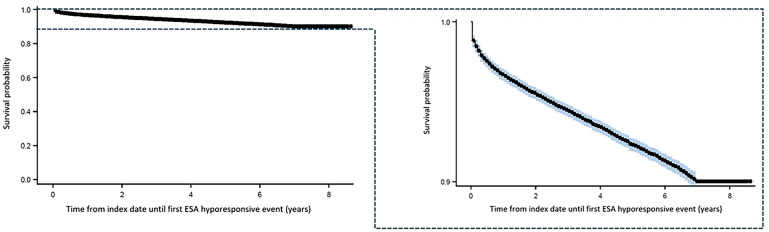

In the overall population, a NICE hyporesponsive event was observed in 4421 patients (5.2%). The incidence rate of NICE hyporesponsiveness was 0.051 per 1000 days and the median time to first hyporesponsive event (in those who experienced an event) was 225 days, with an initial sharp decrease followed by a consistent decline observed in the proportion of patients without a hyporesponsive event shortly after index date (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for the occurrence of first ESA hyporesponsive event after ESA initiation (overall population). Right-hand panel presents data points on a larger scale for clarity. Blue areas indicated a 95% Hall–Wellner band. Crosses indicate censored data points. ESA erythropoiesis-stimulating agent

Of the 4421 patients with NICE hyporesponsiveness, 3475 patients (78.6%) were from Western European countries, 906 patients (20.5%) were from Eastern European countries, and 40 patients (0.9%) were from South Africa.

ESA Hyporesponsiveness Using Alternative Definitions

Overall, an ERI-defined ESA hyporesponsive event was observed in 34,738 patients (40.7%), with an incidence rate of 0.403 per 1000 days. Of these patients, 17,996 (51.8%) were from Eastern European countries and 16,532 (47.6%) were from Western European countries. The incidence rate of ESA hyporesponsiveness per 1000 days was 0.15 (n = 13,142; 15.4%) based on KDIGO and 0.48 (n = 40, 832; 47.9%) based on the CPA.

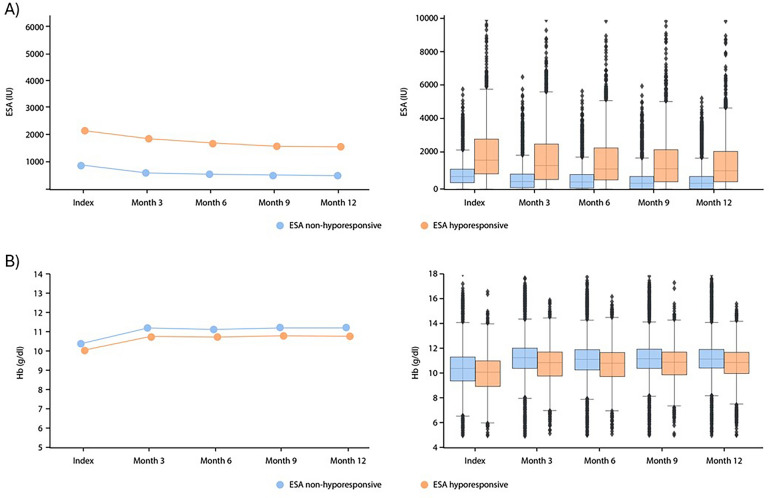

ESA Dose and HB Level over 12 Months

The ESA dose and Hb levels over the first 12 months post ESA initiation for all patients with a hyporesponsive event over the full study period, and for responsive patients (defined according to NICE dosing criteria) are presented in Fig. 3. At index date, the median (IQR) ESA starting dose was 1700.0 (933.3, 2933.3) IU per week in ESA hyporesponders and 733.3 (400.0, 1173.3) IU per week in ESA responders. For both ESA hyporesponders and responders, ESA doses declined over the 12-month period post ESA initiation but appeared to be consistently higher in ESA hyporesponders (Fig. 3). A higher scatter was observed in doses administered to ESA hyporesponders (Fig. 3). After 12 months post ESA initiation, the median ESA dose (IQR) decreased to 1100.0 (466.7, 2200.0) IU per week in ESA hyporesponders and 333.3 (0.0, 733.3) IU per week in ESA responders. At index date, the median (IQR) Hb level was 10.1 (9.0, 11.0) g/dL for ESA hyporesponders and 10.4 (9.4, 11.3) g/dL for the ESA responder group. Similar Hb levels were observed between ESA hyporesponders and ESA responders throughout the 12-month period post ESA initiation, with both groups demonstrating an improvement in Hb within 3 months of ESA initiation (Fig. 3) to final median (IQR) Hb levels of 10.8 (10.0, 11.7) g/dL and 11.2 (10.4, 11.9) g/dL in ESA hyporesponders and ESA responders, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Mean (left) and median (IQR; right) a ESA dose and b Hb levels over the first 12 months post-ESA initiation (index date) in patients with a NICE ESA hyporesponsive event over the full study period and patients with an ESA response. Left-hand panels show mean values. Right-hand panels show box plots, comprising low whiskers (Q1 − 1.5 × IQR), a box denoting the IQR with median line and high whiskers (Q3 + 1.5 × IQR). ESA erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, Hb haemoglobin, IQR interquartile range, NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Q quartile

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in Patients with or Without an ESA Hyporesponsiveness Event Within 1 Year Post ESA Initiation

A total of 2602 patients (58.9% of all hyporesponsive patients) experienced their first NICE-defined hyporesponsive event within 1 year post ESA initiation. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these groups are presented in Table 2 (see Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics at index date for patients with an ESA hyporesponsive event within 1 year post ESA initiation and those without an event within 1 year post ESA initiation

| Characteristics | ESA hyporesponsivea (within 1 year post ESA initiation) (N = 2602) |

ESA responsive (within 1 year post ESA initiation) (N = 82,657) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | n = 2602 | n = 82,657 |

| Mean ± SD | 64.9 ± 16.4 | 63.8 ± 14.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 68.0 (55.0, 78.0) | 66.0 (55.0, 75.0) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 1323 (50.9) | 49 720 (60.2) |

| Body weight, kg | n = 2591 | n = 82,220 |

| Mean ± SD | 62.1 ± 14.2 | 72.4 ± 16.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 60.5 (52.0, 70.2) | 70.5 (60.5, 82.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | n = 2073 | n = 74,433 |

| Mean ± SD | 24.3 ± 5.6 | 27.0 ± 6.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 23.6 (20.9, 26.7) | 26.1 (22.9, 30.1) |

| Hb, g/dLb | n = 2602 | n = 82,544 |

| Mean ± SD | 9.7 ± 1.5 | 10.4 ± 1.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 9.8 (8.7, 10.8) | 10.4 (9.4, 11.3) |

| Ferritin, µg/Lb | n = 2019 | n = 59,376 |

| Mean ± SD | 488.3 ± 522.8 | 488.9 ± 455.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 331.0 (160.1, 638.0) | 359.6 (182.0, 641.8) |

| Transferrin, mg/dLb | n = 1436 | n = 27,967 |

| Mean ± SD | 176.9 ± 49.6 | 181.6 ± 43.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 170.0 (141.0, 205.7) | 177.0 (153.0, 204.0) |

| TSAT, %b | n = 1762 | n = 47,517 |

| Mean ± SD | 22.9 ± 14.5 | 25.3 ± 13.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 20.0 (13.3, 29.0) | 22.7 (16.0, 31.0) |

| Serum iron, µg/dLb | n = 1727 | n = 53,548 |

| Mean ± SD | 52.3 ± 32.1 | 59.1 ± 29.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 46.0 (31.0, 64.2) | 54.0 (39.1, 72.6) |

| TIBC, mg/dLb | n = 1436 | n = 27,967 |

| Mean ± SD | 221.1 ± 62.0 | 227.0 ± 53.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 212.5 (176.3, 257.1) | 221.3 (191.3, 255.0) |

| PTH, ng/Lb | n = 1707 | n = 54, 951 |

| Mean ± SD | 327.8 ± 335.4 | 353.7 ± 329.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 220.0 (107.1, 412.2) | 259.0 (141.0, 450.5) |

| CRP, mg/dLb | n = 1703 | n = 51,698 |

| Mean ± SD | 22.2 ± 35.2 | 19.8 ± 36.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 8.4 (3.1, 24.5) | 6.5 (2.3, 19.2) |

| Albumin, g/dLb | n = 2140 | n = 67,444 |

| Mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| Median (IQR) | 3.5 (3.1, 3.8) | 3.8 (3.5, 4.1) |

| Additional anaemia treatment, n (%)c | 1716 (66.0) | 57,913 (70.1) |

| IV iron, n (%) | 1624 (62.4) | 56,936 (68.9) |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 250 (9.6) | 3510 (4.3) |

| Dialysis efficiency, Kt/V | n = 2499 | n = 78,940 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.0) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) |

| Dialysis type, n (%) | ||

| Haemodialysis | 1500 (57.7) | 49,882 (60.4) |

| HDF | 1072 (41.2) | 31,629 (38.3) |

| PD | 21 (0.8) | 905 (1.1) |

| Other | 9 (0.4) | 241 (0.3) |

| Vascular access for dialysis, n (%) | ||

| AVF | 1033 (43.5) | 44,901 (55.9) |

| AVG | 61 (2.6) | 1660 (2.1) |

| Catheter | 1282 (54.0) | 33,811 (42.1) |

| Missing/unknown | 226 | 2285 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | 295 (11.3) | 11,919 (14.4) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 258 (9.9) | 13,368 (16.2) |

| Hypertension | 1184 (45.5) | 50,981 (61.7) |

| Heart failure | 188 (7.2) | 11,094 (13.4) |

| Drugs acting on RAAS, n (%) | 731 (28.1) | 20,848 (25.2) |

AVF arteriovenous fistula, AVG arteriovenous graft, BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CRP C-reactive protein, ESA erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, Hb haemoglobin, HDF haemodiafiltration, IQR interquartile range, IV intravenous, NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, PD peritoneal dialysis, PTH parathyroid hormone, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SC subcutaneous, SD standard deviation, TIBC total iron binding capacity, TSAT transferrin saturation

aDefined according to NICE dosing criteria for hyporesponsiveness: epoetin alfa ≥ 300 IU/kg/week SC or ≥ 450 IU/kg/week IV, or darbepoetin ≥ 1.5 μg/kg/week

bAt index date (date of ESA initiation)

cDefined as receiving oral or IV iron and blood transfusions in addition to ESA treatment; if the patient received only ESA treatment, they were classed as having received no further anaemia treatment

While no formal statistical comparisons were performed, differences in sex distribution were observed between the two groups: approximately equal proportions of men and women experienced an ESA hyporesponsive event within 1 year, but a greater proportion of men (60.2%) than women (39.8%) were responsive to ESA. Comorbidities of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure were reported in a smaller proportion of patients with a hyporesponsive event within 1 year versus those without (Table 2).

The proportion of patients receiving HDF was similar between groups and median dialysis efficiency was greater than 1.2 Kt/V in both groups. A greater proportion of patients with a hyporesponsive event within 1 year underwent dialysis via catheter (54.0%) than those without (42.1%). Mean ± SD dialysis efficiency was 1.7 ± 0.5 Kt/V in those with an event within 1 year versus 1.6 ± 0.4 Kt/V in those who did not have an event; median (IQR) values were 1.7 (1.4, 2.0) Kt/V and 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) Kt/V, respectively.

Median TSAT appeared to be lower in patients who had an ESA hyporesponsive event within 1 year than those who did not, while median ferritin concentrations were similar between groups. A higher median C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration was reported in those with an event within 1 year than those without, while parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels appeared lower (Table 2).

Treatment at Index Date for ESA Hyporesponders Within 1 Year Post ESA Initiation

In the population with ESA hyporesponsiveness within 1 year post index date, the median (IQR) ESA starting dose at index date was 2500.0 (1466.7, 3800.0) IU per week and 733.3 (400.0, 1173.3) IU per week in those without an event after 1 year. The proportions of patients receiving epoetin alfa (~ 60%) or darbepoetin (~ 40%) were similar between groups, and IV ESA was administered to a higher proportion of patients with an event within 1 year post index than those without (86.1% versus 48.8%). The proportion of patients receiving IV iron was lower in those with an event within 1 year post index than those without (62.4% versus 68.9%), while twice as many patients with an event after 1 year post index received blood transfusions than those without an event after 1 year post index (9.6% versus 4.3%).

Isolated, Intermittent, and Chronic ESA Hyporesponsiveness

Hyporesponsiveness (NICE) was intermittent in most patients (n = 3874; 87.6%) and the remainder were isolated episodes (n = 547; 12.4%); none were chronic. No notable differences were observed in the overall demographic and clinical characteristics between isolated and intermittent ESA hyporesponders (Supplementary Material, Table S3). Median (IQR) ESA dose at index date was similar for patients with isolated episodes (1733.3 [900.0, 2833.3] IU) or intermittent ESA episodes (1686.7 [933.3, 2966.7] IU).

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of patients with anaemia of CKD receiving RRT and ESA treatment, the observed incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness, based on NICE dosing criteria, was 5.2% [7]. When defining hyporesponsiveness using ERI, the KDIGO guidelines, and the CPA [6, 20, 21], incidence was 40.7%, 15.4%, and 47.9%, respectively. As ESA hyporesponsiveness is associated with increased mortality rates and poor outcomes [4, 5, 28, 29], its recognition and an understanding of optimal management of anaemia in this patient group is important. In particular, the CPA definition, which compared ESA dose requirements for patients treated within the same country, may provide a convenient measure that reduces variability in results across different regions based on healthcare practices and socioeconomic factors [20].

The present study is the first to explore the incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness using varied definitions in the same patient population from a broad geographical region. Prior studies have also shown that the incidence of ESA hyporesponsiveness can vary widely according to the definition applied, with rates of 10–15% reported in patients with CKD receiving dialysis [22–24]. These previously reported incidences are higher than that identified using NICE dosing criteria in the present study, but lower than that observed when ERI, KDIGO, or CPA criteria were used. Potential reasons for the low incidence of NICE hyporesponsiveness include the substantial proportion (approximately 40%) of patients receiving HDF, and the finding that dialysis efficiency was greater than the guideline minimum standard of 1.2 Kt/V [30]; these factors may have contributed to the low observed rate of hyporesponsiveness by removing uraemic toxicity, a contributing factor to the pathophysiology of anaemia of CKD [31, 32].

The disparity in reported hyporesponsiveness incidence rates has implications for clinical practice. KDIGO guidelines recommend ameliorating care regimens in patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness by avoiding further ESA dose escalation beyond double the initial weight-based dose or dose at which they had been stable and treating underlying causes of ESA hyporesponsiveness [6]. However, it is possible that, depending on the criteria used, some patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness may be undiagnosed and remain on suboptimal treatment and unnecessary ESA dose escalation. Our findings highlight the need for improved awareness of ESA hyporesponsiveness, even at thresholds which typically may not meet criteria as described by guidelines, such as NICE or KDIGO. Careful assessment of patients on high ESA dose, regardless of hyporesponsiveness criteria, is warranted.

The apparent higher ESA doses in hyporesponsive than responsive patients observed in the present analysis aligns with previous reports [18, 19]. However, ESA-hyporesponsive and ESA-responsive patients had similar Hb levels, and both groups showed an improvement within 3 months after treatment initiation. It is worth noting that one reason for higher ESA doses in ESA hyporesponders versus responders may be that ESA hyporesponsiveness was defined according to NICE ESA dosing criteria. Notably, doses remained higher in hyporesponsive than in responsive patients over 12 months, suggesting some degree of persistent lower sensitivity and poorer response to ESA. Previous findings have shown that chronic hyporesponsiveness is associated with a greater requirement for blood transfusions and increased mortality than isolated hyporesponders or responders [23]. In the present study, while no patients met the criteria for chronic hyporesponsiveness, the majority (87.6%) were intermittent hyporesponders with generally consistent index-date demographic and clinical characteristics between intermittent and isolated hyporesponders. These findings contrast with the previous study, where 31.8% of hyporesponsive patients had chronic ESA hyporesponsiveness and significantly lower Hb and TSAT alongside greater PTH levels than ESA responders [23]. This study also applied different criteria to define both overall ESA hyporesponsiveness and chronic hyporesponsiveness [23]. These previous findings and our data highlight the disparity between different definitions of ESA hyporesponsiveness. However, our study identified a group of patients with higher ESA doses to achieve Hb targets, suggesting careful monitoring would be necessary in these patients.

Approximately 60% of hyporesponsive patients experienced their first NICE-defined hyporesponsive event (as per NICE dosing criteria) within the first year following ESA initiation. We further analysed the time to the first hyporesponsive event using a Kaplan–Meier curve, which demonstrated a steady decline in survival probability, suggesting that the occurrence of events continued at a similar rate beyond the first year. Given that KDIGO guidelines criteria define a patient as ESA hyporesponsive if an increase in Hb level from baseline is not observed after the first month of ESA treatment with appropriate weight-based dosing [6], this finding highlights further the importance of careful consideration towards ESA hyporesponsiveness criteria selection. Owing to the clinical importance of early ESA hyporesponsiveness, index date, and given that the majority of patients in the present analysis had their first hyporesponsive event within 1 year post index date, demographic and clinical characteristics were explored in those who developed an event within 1 year and those who did not. Persistent inflammation is an important component of CKD and its pathophysiology [33]. Patients with CKD frequently display increased pro-inflammatory activity, with elevated CRP and cytokines [33–35], along with decreased activity of anti-inflammatory cytokines [33]. Findings from the present analysis reflect this current understanding, with apparent higher CRP levels observed in 1-year hyporesponder patients than those without an event within 1 year, although there were high degrees of missing data. Interaction of inflammatory cytokines with hepcidin may underlie ESA hyporesponsiveness [36]. Inflammation may stimulate production of hepcidin [37], which in turn downregulates the iron exporter, ferroportin, resulting in functional iron deficiency and reduced availability of iron for erythropoiesis [37]. Consequently, inflammation could work antagonistically to ESAs, which may contribute to patients requiring higher ESA doses to achieve target Hb levels. Newer hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PH) inhibitors may provide a potential alternative treatment strategy for patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness as they promote hypoxia-induced expression of erythropoietin while suppressing hepcidin and other pro-inflammatory cytokines [17, 38]. Recent evidence, including real-world evidence and an umbrella review assessing data from multiple metanalyses, suggests that HIF-PH inhibitors are effective in increasing haemoglobin levels, decreasing inflammatory markers, and hepcidin levels and improving iron transport [39–42].

Of note, at index date among patients with an ESA hyporesponsive event within 1 year, a lower proportion received IV iron and a higher proportion received blood transfusions than those without an event after 1 year. These findings contrast with previous evidence demonstrating ESA dose reductions and fewer blood transfusions with higher IV iron usage in patients with anaemia of CKD receiving dialysis [43]. However, it is important to note that IV iron dose was not available to provide further context for these findings. We noted an apparent greater incidence of blood transfusions in patients with a hyporesponsive event within 1 year than in those without, which is supported by previous data showing greater blood transfusion rates among patients with dialysis-dependent CKD and hyporesponsiveness to ESAs [18]. In our study, ferritin levels at index date were similar between patients with and without hyporesponsive events within 1 year, whereas conflicting results have been reported previously, with either higher or similar ferritin levels in ESA-hyporesponsive and ESA-responsive patients [18, 19]. However, since the elevated ferritin levels often reported in patients with CKD may be attributed to underlying systemic inflammation [44], this may not be a suitable marker of iron stores in this population.

The present retrospective study explored various definitions of ESA hyporesponsiveness and clinical characteristics in a large population of patients with anaemia of CKD receiving dialysis at Nephrocare dialysis clinics. However, the current findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Given its observational, retrospective nature, the study was subject to the potential bias inherent in any uncontrolled observational study. The study was purely exploratory, with all analyses being descriptive in nature; as such, no association or causality can be inferred from these results. Confounding may have occurred according to ESA treatment indication or by country/region. While guideline recommendations are available, the usual ESA starting dose may have been influenced by country clinical experience, and individual physicians’ discretion. Patients’ ESA dosing history prior to inclusion in EuCliD is unknown, and non-ESA-naïve patients could have been included. Thus, Hb levels at index date may be impacted by previous treatment. Patients receiving methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta were not included in the present analysis, as these types of ESAs are not included in the NICE-defined criteria for hyporesponsiveness; however, records were included from patients treated with the two most commonly used ESAs in the studied regions (darbepoetin and epoetin), providing results that are generalisable to the populations in these regions. Finally, data were captured from electronic medical records, which may have incomplete or missing information; for example, information on IV iron dose was unknown and missing data were observed for parameters relating to iron metabolism (e.g. among patients who were hyporesponders or responders after 1 year: TSAT [hyporesponders 840/2602; responders 35,140/82,657]), inflammation markers (e.g. CRP [hyporesponders 899/2602; responders 30,959/82,657]), and parathyroid hormone (hyporesponders 895/2602; responders 27,706/82,657). Owing to the retrospective nature of this analysis, a single aspirational Hb target criterion for NICE was not applied to the definition of ESA hyporesponsiveness; however, the Hb values are expected to be in line with those recommended in clinical guidelines (typically 10–12 g/dL) [6, 7]. As comorbidity data were dependent on the patient and healthcare providers voluntarily reporting comorbidities to the dialysis centre, data were incomplete, and there was no delineation between missing data and absence of a comorbidity.

Conclusions

The present study was the first to use alternative definitions of ESA hyporesponsiveness across a large, broad, and geographically diverse population of patients with anaemia of CKD who were receiving RRT. Results show a large variation in incidence rates when applying different definitions of ESA, as has been noted across previous studies, which highlights the differences in clinical practice and the difficulty of capturing such differences within one definition of ESA hyporesponsiveness. These data have important clinical implications, highlighting the need for careful assessment of patients with higher ESA dose, even if they do not fall within defined ESA hyporesponsiveness ranges. We also found persistently higher ESA doses over 12 months in ESA hyporesponders than responders, suggesting residual persistent hyporesponsiveness and the need for continued management of patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Hannah Brown, PhD, of Lumanity for providing medical writing support/editorial support, which was funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc. in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Author Contributions

Conception: Christopher Atzinger, Alina Jiletcovici, Najib Khalife; study design and conduct: Christopher Atzinger, Alina Jiletcovici, Robert Snijder, Kirsten Leyland, Najib Khalife, Astrid Feuersenger; data acquisition: Hans-Jürgen Arens, Luca Neri, Mario Garbelli, Otto Arkossy; analysis and interpretation: all authors; including Mahmood Ali; writing: all authors.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study, the Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc.

Data Availability

Researchers may request access to anonymised participant-level data, trial-level data and protocols from Astellas-sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing see: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Hans-Jürgen Aren, Luca Neri, Astrid Feuersenger, Mario Garbelli and Otto Arkossy are employees of Fresenius Medical Care, contracted by Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc. to conduct the study. Hans-Jürgen Aren reports Fresenius Medical Care stock shares. Christopher Atzinger and Alina Jiletcovici are employees of Astellas Pharma Global Development Inc. Alina Jiletcovici reports Eli Lilly stock shares. Robert Snijder is an employee of Astellas Pharma Europe B.V. Kirsten Leyland, Najib Khalife and Mahmood Ali are employees of Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd.

Ethical Approval

All data were pseudonymised and all patients provided written informed consent for access and secondary use of their pseudonymised clinical data for research purposes. According to the National Institutes of Health definition of human subject research, this study falls under the exempt human subjects research category [27].

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: These data were presented in part as a poster presentation at the 60th European Renal Association Congress, June 15–18, 2023, Milan, Italy.

References

- 1.Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2022;12(1):7–11. 10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Chronic Kidney Disease – Level 3 cause. 2022. https://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/chronic-kidney-disease-level-3-cause. Accessed 2023 Dec 15.

- 3.Nakhoul G, Simon JF. Anemia of chronic kidney disease: treat it, but not too aggressively. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(8):613–24. 10.3949/ccjm.83a.15065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palaka E, Grandy S, van Haalen H, McEwan P, Darlington O. The impact of CKD anaemia on patients: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes – a systematic literature review. Int J Nephrol. 2020;1(2020):7692376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Haalen H, Jackson J, Spinowitz B, Milligan G, Moon R. Impact of chronic kidney disease and anemia on health-related quality of life and work productivity: analysis of multinational real-world data. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Anemia Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(4):279–335. https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/KDIGO-2012-Anemia-Guideline-English.pdf. Accessed 2022 Aug 22.

- 7.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Guidelines – Chronic Kidney Disease: Assessment and management. 2021. [PubMed]

- 8.Portolés J, Martín L, Broseta JJ, Cases A. Anemia in chronic kidney disease: from pathophysiology and current treatments, to future agents. Front Med. 2021;8(March):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancelo-Hidalgo MJ, Castelo-Branco C, Palacios S, et al. Tolerability of different oral iron supplements: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):291–303. 10.1185/03007995.2012.761599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolkien Z, Stecher L, Mander AP, Pereira DIA, Powell JJ. Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Strnad P, editor. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117383. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutiérrez OM. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia in CKD and end-stage kidney disease. Kidney Int Reports. 2021;6(9):2261–9. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Shepshelovich D, Rozen-Zvi B, Avni T, Gafter U, Gafter-Gvili A. Intravenous versus oral iron supplementation for the treatment of anemia in CKD: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(5):677–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Vecchio L, Ekart R, Ferro CJ, et al. Intravenous iron therapy and the cardiovascular system: risks and benefits. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1067–76. 10.1093/ckj/sfaa212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Agarwal AK. Iron metabolism and management: focus on chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2021;11(1):46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikhail A, Brown C, Williams JA, et al. Renal association clinical practice guideline on anaemia of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez-García R, Varas J, Cives A, et al. Increased mortality in haemodialysis patients administered high doses of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: a propensity score-matched analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(4):690–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfx269. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wu HHL, Chinnadurai R. Erythropoietin-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness in patients living with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Dis. 2022;8(2):103–14. 10.1159/000521162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Cizman B, Smith HT, Camejo RR, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of erythropoiesis-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness in the post-bundling era. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):589–599.e1. 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.McMahon LP, Cai MX, Baweja S, et al. Mortality in dialysis patients may not be associated with ESA dose: A 2-year prospective observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13(1):40. 10.1186/1471-2369-13-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Berns JS. Hyporesponse to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) in chronic kidney disease. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hyporesponse-to-erythropoiesis-stimulating-agents-esas-in-chronic-kidney-disease#H3332399465.

- 21.Chait Y, Kalim S, Horowitz J, et al. The greatly misunderstood erythropoietin resistance index and the case for a new responsiveness measure. Hemodial Int. 2016;20(3):392–8. 10.1111/hdi.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo J, Jensen DE, Maroni BJ, Brunelli SM. Spectrum and burden of erythropoiesis-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness among contemporary hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(5):763–71. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sibbel SP, Koro CE, Brunelli SM, Cobitz AR. Characterization of chronic and acute ESA hyporesponse: a retrospective cohort study of hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):144. 10.1186/s12882-015-0138-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macdougall IC, Meadowcroft AM, Blackorby A, et al. Regional Variation of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Hyporesponsiveness in the Global Daprodustat Dialysis Study (ASCEND-D). Am J Nephrol. 2023;54(1–2):1–13. 10.1159/000528696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcelli D, Kirchgessner J, Amato C, et al. EuCliD (European Clinical Database): a database comparing different realities. J Nephrol. 2001;14 Suppl 4:S94–100. [PubMed]

- 26.Jordan J, Breckles J, Leung V, Hopkins M, Battistella M. Conversion from epoetin alfa to darbepoetin alfa: effects on patients’ hemoglobin and costs to canadian dialysis centres. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2012;65(6):443–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US National Institutes of Health. Definition of Human Subjects Research. Exempt Human Subjects Research Infographic. 2020.

- 28.Bae MN, Kim SH, Kim YO, et al. Association of erythropoietin-stimulating agent responsiveness with mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143348. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narita I, Hayashi T, Maruyama S, et al. Hyporesponsiveness to erythropoiesis-stimulating agent in non-dialysis-dependent CKD patients: The BRIGHTEN study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(11):e0277921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daugirdas JT, Depner TA, Inrig J, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884–930. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hamza E, Metzinger L, Metzinger-Le Meuth V. Uremic toxins affect erythropoiesis during the course of chronic kidney disease: a review. Cells. 2020;9(9):2039. 10.3390/cells9092039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Yamamoto S, Kazama JJ, Wakamatsu T, et al. Removal of uremic toxins by renal replacement therapies: a review of current progress and future perspectives. Ren Replace Ther. 2016;2(1):43. 10.1186/s41100-016-0056-9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akchurin OM, Kaskel F. Update on inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Blood Purif. 2015;39(1–3):84–92. 10.1159/000368940. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Gluba-Brzózka A, Franczyk B, Olszewski R, Rysz J. The influence of inflammation on anemia in CKD patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):725. 10.3390/ijms21030725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Xu G, Luo K, Liu H, Huang T, Fang X, Tu W. The progress of inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2015;37(1):45–9. 10.3109/0886022X.2014.964141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deicher R, Hörl WH. Hepcidin: a molecular link between inflammation and anaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(3):521–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Iron balance and the role of hepcidin in chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36(2):87–93. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Weir MR. Managing anemia across the stages of kidney disease in those hyporesponsive to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Nephrology. 2021;52(6):450–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren S, Yao X, Li Y, Zhang Y, Tong C, Feng Y. Efficacy and safety of hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor treatment for anemia in chronic kidney disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1296702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mima A, Horii Y. Treatment of renal anemia in patients with hemodialysis using hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) stabilizer, roxadustat: a short-term clinical study. In Vivo (Brooklyn). 2022;36(4):1785–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mima A. Enarodustat treatment for renal anemia in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. In Vivo (Brooklyn). 2023;37(2):825–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minutolo R, Liberti ME, Simeon V, et al. Efficacy and safety of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in patients with chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis of phase 3 randomized controlled trials. Clin Kidney J. 2023;17(1):sfad143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macdougall IC, White C, Anker SD, et al. Intravenous iron in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batchelor EK, Kapitsinou P, Pergola PE, Kovesdy CP, Jalal DI. Iron deficiency in chronic kidney disease: updates on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(3):456–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Researchers may request access to anonymised participant-level data, trial-level data and protocols from Astellas-sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing see: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx.