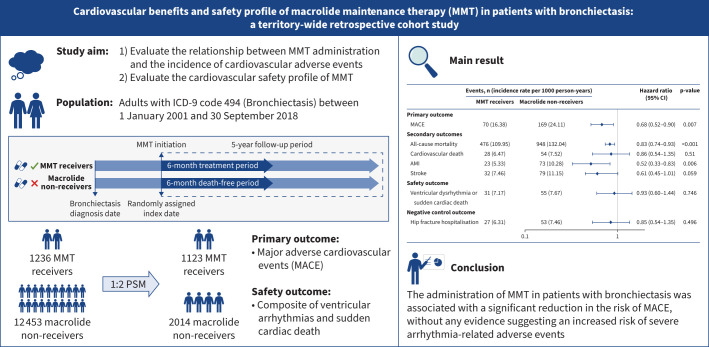

Graphical abstract

Overview of the study. MMT: macrolide maintenance therapy; ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; PSM: propensity score matching; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; AMI: acute myocardial infarction.

Abstract

Background

Macrolide maintenance therapy (MMT) has demonstrated notable efficacy in reducing exacerbation in patients with bronchiectasis, which is a major risk factor for cardiovascular events. However, a comprehensive assessment of the cardiovascular benefits and safety profile of MMT in this population is lacking.

Methods

This territory-wide cohort study analysed patients diagnosed with bronchiectasis in Hong Kong between 2001 and 2018. Patients were classified as MMT receivers or macrolide non-receivers based on the administration of MMT. Propensity score (PS) matching was employed for confounding factors adjustment. The primary outcome of interest was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and stroke. The safety outcome was the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was utilised to compare the incidence of outcomes across the two groups.

Results

A total of 22 895 patients with bronchiectasis were identified. Following 1:2 PS matching, the final cohort consisted of 3137 individuals, with 1123 MMT receivers and 2014 macrolide non-receivers. MMT administration was associated with a significantly reduced risk of MACE (16.38 versus 24.11 events per 1000 person-years; hazard ratio (HR) 0.68, 95% CI 0.52–0.90). Importantly, the use of MMT was not associated with elevated risk of ventricular arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death (7.17 versus 7.67 events per 1000 person-years; HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.60–1.44).

Conclusions

The administration of MMT in patients with bronchiectasis was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of MACE, without any evidence suggesting an increased risk of severe arrhythmia-related adverse events.

Shareable abstract

In people living with bronchiectasis, macrolide maintenance therapy was associated with significant risk reduction in major cardiovascular adverse events, while not associated with elevated risk of ventricular arrythmia or sudden cardiac death https://bit.ly/4fMB0qs

Introduction

The high burden of cardiovascular comorbidities among people living with chronic lung diseases such as bronchiectasis is increasingly recognised. In comparison with the general population, individuals with bronchiectasis have a three-fold increased risk of developing coronary heart diseases and a five-fold elevated risk of stroke incidence [1]. Consequently, cardiovascular-related death ranks second only to mortality directly attributed to bronchiectasis itself [2]. Thus, mitigating the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in bronchiectasis assumes great importance in improving long-term survival in this patient population.

A key principle in addressing cardiopulmonary risk is identifying shared mechanisms such that interventions with cross-disease beneficial effects can be implemented [3]. The precise mechanisms driving the increased prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in people living with bronchiectasis have not been clearly elucidated, yet a consistent relationship between acute exacerbations and increased incidence of cardiovascular events has been identified in bronchiectasis and other diseases, including COPD [4–6]. Acute exacerbations are associated with increased pulmonary and systemic inflammation as well as increased cardiac workload which may combine to trigger cardiovascular events. In bronchiectasis, macrolide maintenance therapy (MMT) is recommended by multiple national and international guidelines for those experiencing frequent exacerbations due to its ability to reduce exacerbation frequency by exerting a combination of anti-inflammatory, antiviral and, perhaps to a lesser extent, antimicrobial effects [7]. Although the broader anti-inflammatory properties of MMT suggest potential cardioprotective effects, historical studies reported an increased incidence of sudden cardiac death or ventricular tachyarrhythmias associated with the use of short-term courses of macrolides [8–10]. The impact of MMT on cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with bronchiectasis has not been extensively studied and thus the balance of risk or potential benefits is unclear.

In this territory-wide cohort study, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between MMT administration and the incidence of cardiovascular adverse events, while also evaluating the associated risk of severe arrhythmia-related outcomes.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS) database. CDARS is an electronic health record database managed by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority. This comprehensive database encompasses 43 hospitals, 49 specialist outpatient clinics and 73 general outpatient clinics, collectively covering >90% of Hong Kong's population (over 7.5 million individuals) since 1993. The data within CDARS have been extensively validated, demonstrating high coding accuracy, which has enabled numerous high-quality, population-based studies to be conducted [11–13]. This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong Western Cluster.

Study population and exposure

We conducted a retrospective cohort study mimicking an as-treated, new-user design to evaluate the cardiovascular protective effect and safety of MMT among patients diagnosed with bronchiectasis. Eligible participants included all patients aged ≥18 years with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code 494 (Bronchiectasis) between 1 January 2001 and 30 September 2018. Exposure of interest was the administration of MMT, which was defined as receiving macrolide antibiotics in four specific regimens, each lasting a minimum of 6 months: 1) azithromycin 500 mg, three times per week; 2) azithromycin 250 mg, daily; 3) erythromycin 400 mg (equivalent to erythromycin base 250 mg), twice daily; and 4) azithromycin 250 mg, three times per week. The effectiveness of the first three regimens in reducing bronchiectasis exacerbation frequency has been validated by pivotal clinical trials [14–16]. The fourth regimen, although lacking trial data support, is commonly prescribed in clinical settings, particularly for patients intolerant to higher azithromycin dosages [7]. A 14-day grace period was allowed for intermittent adherence. Patients receiving macrolides at other doses or shorter duration were excluded, as well as those lacking precise records of dosage and duration of macrolide use. Macrolide antibiotics prescription details are summarised in supplementary table S1. To mitigate potential immortal time bias, wherein MMT receivers are granted a fixed 6-month period during which death could not have occurred, macrolide non-receivers who died within 6 months after enrolment were excluded from analysis.

For MMT receivers, the index date was defined as the date of their first drug prescription. For macrolide non-receivers, the index date was randomly assigned as the date of an outpatient visit [17].

Outcomes and follow-up

The primary outcome of interest was three-point major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), a composite of cardiovascular death, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke. Secondary outcomes included each component of MACE and all-cause mortality. The safety outcome was a composite of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. We chose hip fracture hospitalisation as negative control outcome in the comparison analysis. Each individual was followed up for a fixed duration of 5 years. Follow-up started the day after the index date and lasted until the occurrence of study outcomes, death or the last day of data collection, whichever came first.

Covariates

Covariates included potential confounders and variables known to be risk factors for the study outcomes. Age, sex, obesity, alcohol use, smoking, bronchiectasis diagnosis calendar year, interval between diagnosis and index date, exacerbation incidence within 1 year preceding the index date, chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, use of drugs (inhaled antibiotics, inhaled or oral corticosteroids, anti-platelet drugs and statins), and history of comorbidities (stroke, unstable angina hospitalisation, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting, AMI, congestive heart failure (CHF), arrythmia, chronic renal failure (CRF), peripheral artery diseases, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, liver diseases, diabetes, cancer and COPD) were collected as covariates. The definitions used to identify the covariates are listed in supplementary table S2.

Statistical analysis

Eligible patients were classified into MMT receivers and macrolide non-receivers, based on their exposure to MMT. Propensity score (PS) matching was employed for confounding control. PSs were calculated by fitting multivariable logistic regression models that estimated the probability of receiving MMT. The aforementioned baseline covariates were included in the regression model. The nearest-neighbour method was used to match MMT receivers with macrolide non-receivers, with a 1:2 ratio and a maximum calliper of 0.02 of the PS. A standardised mean difference (SMD) <0.1 between the matched cohorts was considered as well matched.

The numbers of incidences (events) and incidence rates per 1000 person-years in the cohort were calculated. Cox proportional hazards models were utilised to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence intervals. We used the Kaplan–Meier method to visualise the cumulative curve of the primary outcome over time and used log-rank tests to compare hazard rates between the two groups. Number needed to treat (NNT), the reciprocal of the risk difference between MMT receivers and macrolide non-receivers, was calculated to indicate the absolute risk reduction. Furthermore, we used a Poisson regression model to compare exacerbation frequency between the two groups within 6 months after the index date. A logistic regression model was employed to estimate the odds ratios for patients who underwent at least one exacerbation within 6 months after the index date, comparing MMT receivers to macrolide non-receivers.

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis were performed to evaluate the consistency and robustness of our findings. In order to address the concern for unmeasured confounding and a healthy user effect, we conducted a logistic regression analysis to elucidate any potential association between MMT and the occurrence of MACE before the index date. Furthermore, we conducted an exploratory analysis to investigate the potential association between the dosage and duration of macrolide antibiotics and MACE incidence. Details on the methodology for these analyses can be found in the supplementary material.

All statistical analyses and figure graphing were performed using R version 4.3.1 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 22 895 individuals diagnosed with bronchiectasis were identified from the CDARS database spanning the years 2001 to 2018. Among them, 13 689 individuals met the inclusion criteria, with 1236 MMT receivers and 12 453 macrolide non-receivers (supplementary figured S1 and S2). In general, MMT receivers tended to be younger, had lower rates of smoking and alcohol consumption, and exhibited more severe respiratory conditions (i.e. longer bronchiectasis duration, higher exacerbation incidence, higher burden of P. aeruginosa and COPD, and more frequent use of corticosteroids and inhaled antibiotics) (table 1). Conversely, macrolide non-receivers had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities and cardiac drug utilisation (i.e. ischaemic stroke, CHF, arrythmia, CRF, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and utilisation of aspirin and statin) (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics before and after propensity score (PS) matching

| Before PS matching | After PS matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolide non-receivers (n=12 453) | MMT receivers (n=1236) | Overall (n=13 689) | SMD | Macrolide non-receivers (n=2014) | MMT receivers (n=1123) | Overall (n=3137) | SMD | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, years | 70.2±14.3 | 66.4±14.1 | 69.9±14.3 | 0.273 | 67.5±15.2 | 67.3±13.8 | 67.4±14.7 | 0.019 |

| Male | 5637 (45.3) | 620 (50.2) | 6257 (45.7) | 0.098 | 1003 (49.8) | 556 (49.5) | 1559 (49.7) | 0.006 |

| Ever-drinker | 749 (6.0) | 31 (2.5) | 780 (5.7) | 0.174 | 63 (3.1) | 29 (2.6) | 92 (2.9) | 0.033 |

| Ever-smoker | 1419 (11.4) | 60 (4.9) | 1479 (10.8) | 0.241 | 91 (4.5) | 58 (5.2) | 149 (4.7) | 0.030 |

| Obesity | 159 (1.3) | 5 (0.4) | 164 (1.2) | 0.096 | 5 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 9 (0.3) | 0.020 |

| Diagnosis calendar year | 0.196 | 0.031 | ||||||

| 2001–2005 | 2881 (23.1) | 277 (22.4) | 3158 (23.1) | 481 (23.9) | 254 (22.6) | 735 (23.4) | ||

| 2006–2010 | 2891 (23.2) | 380 (30.7) | 3271 (23.9) | 601 (29.8) | 340 (30.3) | 941 (30.0) | ||

| 2011–2015 | 4009 (32.2) | 382 (30.9) | 4391 (32.1) | 616 (30.6) | 347 (30.9) | 963 (30.7) | ||

| After 2015 | 2672 (21.5) | 197 (15.9) | 2869 (21.0) | 316 (15.7) | 182 (16.2) | 498 (15.9) | ||

| Bronchiectasis duration (years) | 1.46±3.27 | 4.48±4.71 | 1.73±3.53 | 0.745 | 3.60±5.08 | 3.98±4.29 | 3.73±4.82 | 0.080 |

| Bronchiectasis severity | ||||||||

| Exacerbation incidence, 1 year before index date | 0.516 | 0.061 | ||||||

| 0 | 5812 (46.7) | 426 (34.5) | 6238 (45.6) | 717 (35.6) | 401 (35.7) | 1118 (35.6) | ||

| 1 | 4520 (36.3) | 335 (27.1) | 4855 (35.5) | 607 (30.1) | 314 (28.0) | 921 (29.4) | ||

| 2 | 1210 (9.7) | 195 (15.8) | 1405 (10.3) | 318 (15.8) | 178 (15.9) | 496 (15.8) | ||

| ≥3 | 911 (7.3) | 280 (22.7) | 1191 (8.7) | 372 (18.5) | 230 (20.5) | 602 (19.2) | ||

| Microbiology | ||||||||

| Chronic P. aeruginosa infection | 2215 (17.8) | 669 (54.1) | 2884 (21.1) | 0.818 | 923 (45.8) | 563 (50.1) | 1486 (47.4) | 0.086 |

| Bronchiectasis treatment | ||||||||

| Inhaled antibiotics | 22 (0.2) | 8 (0.6) | 30 (0.2) | 0.074 | 10 (0.5) | 6 (0.5) | 16 (0.5) | 0.005 |

| Corticosteroids | 4645 (37.3) | 935 (75.6) | 5580 (40.8) | 0.839 | 1421 (70.6) | 825 (73.5) | 2246 (71.6) | 0.065 |

| Other medications | ||||||||

| Aspirin | 2496 (20.0) | 144 (11.7) | 2640 (19.3) | 0.231 | 259 (12.9) | 140 (12.5) | 399 (12.7) | 0.012 |

| Statins | 1759 (14.1) | 83 (6.7) | 1842 (13.5) | 0.244 | 143 (7.1) | 82 (7.3) | 225 (7.2) | 0.008 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| History of stroke | 795 (6.4) | 45 (3.6) | 840 (6.1) | 0.126 | 80 (4.0) | 41 (3.7) | 121 (3.9) | 0.017 |

| History of unstable angina hospitalisation | 124 (1.0) | 4 (0.3) | 128 (0.9) | 0.083 | 11 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 15 (0.5) | 0.028 |

| History of PCI or CABG | 241 (1.9) | 10 (0.8) | 251 (1.8) | 0.097 | 19 (0.9) | 10 (0.9) | 29 (0.9) | 0.006 |

| History of AMI | 341 (2.7) | 20 (1.6) | 361 (2.6) | 0.077 | 36 (1.8) | 20 (1.8) | 56 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1211 (9.7) | 86 (7.0) | 1297 (9.5) | 0.100 | 158 (7.8) | 83 (7.4) | 241 (7.7) | 0.017 |

| Arrhythmias | 1290 (10.4) | 82 (6.6) | 1372 (10.0) | 0.134 | 156 (7.7) | 80 (7.1) | 236 (7.5) | 0.024 |

| Chronic renal failure | 312 (2.5) | 12 (1.0) | 324 (2.4) | 0.118 | 26 (1.3) | 12 (1.1) | 38 (1.2) | 0.021 |

| Peripheral artery diseases | 1277 (10.3) | 104 (8.4) | 1381 (10.1) | 0.063 | 167 (8.3) | 97 (8.6) | 264 (8.4) | 0.012 |

| Hypertension | 3324 (26.7) | 243 (19.7) | 3567 (26.1) | 0.167 | 407 (20.2) | 230 (20.5) | 637 (20.3) | 0.007 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 809 (6.5) | 49 (4.0) | 858 (6.3) | 0.114 | 92 (4.6) | 48 (4.3) | 140 (4.5) | 0.014 |

| Liver diseases | 668 (5.4) | 58 (4.7) | 726 (5.3) | 0.031 | 97 (4.8) | 53 (4.7) | 150 (4.8) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | 1415 (11.4) | 119 (9.6) | 1534 (11.2) | 0.057 | 197 (9.8) | 107 (9.5) | 304 (9.7) | 0.009 |

| Cancer | 1173 (9.4) | 180 (14.6) | 1353 (9.9) | 0.159 | 272 (13.5) | 158 (14.1) | 430 (13.7) | 0.016 |

| COPD | 2496 (20.0) | 434 (35.1) | 2930 (21.4) | 0.342 | 684 (34.0) | 382 (34.0) | 1066 (34.0) | 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean±sd or n (%), unless otherwise stated. MMT: macrolide maintenance therapy; SMD: standardised mean difference; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; AMI: acute myocardial infraction.

After 1:2 PS matching, 1123 MMT receivers were successfully matched with 2014 non-receivers. The baseline characteristics between the two groups were well balanced with SMDs <0.1. In the PS-matched cohort, the MMT receivers and macrolide non-receivers had similar proportions of patients with cardiovascular complications and cardiovascular drug usage; they also had similar diagnosis year, bronchiectasis duration, P. aeruginosa prevalence and exacerbation frequency within 1 year prior to the index date (supplementary figure S3).

Primary and secondary outcome analysis

In the unmatched overall cohort, a total of 1326 (9.69%) MACE occurred during the 5-year follow-up period. Patients who experienced MACE had a significantly higher frequency of exacerbations within 1 year preceding the index date (mean±sd event count: 1.88±2.02 versus 1.48±1.99; p<0.001) and 6 months after the index date (mean±sd event count: 0.70±1.22 versus 0.55±1.12; p<0.001) compared with those who did not experience MACE.

In the PS-matched cohort, 70 MMT receivers and 169 macrolide non-receivers experienced MACE (16.38 versus 24.11 events per 1000 person-years), indicating a significantly reduced risk of MACE associated with MMT (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.52–0.90) (figure 1). In addition, the estimated 5-year NNT to prevent one MACE in the PS-matched cohort was 46 (95% CI 25–337).

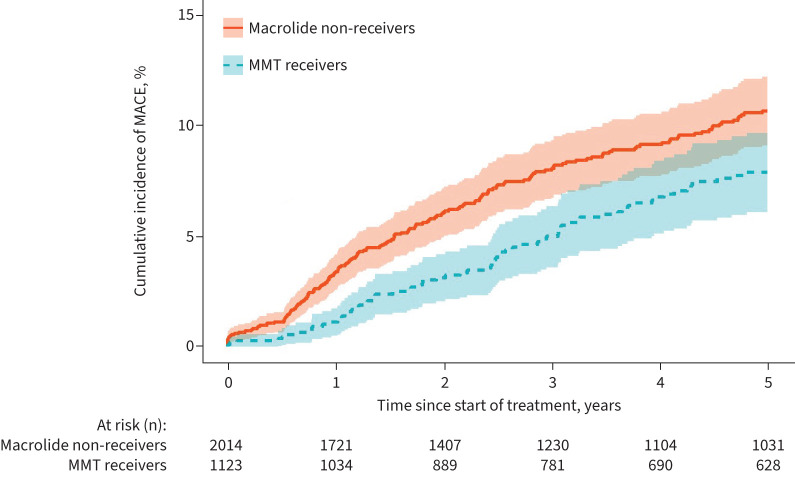

FIGURE 1.

Outcomes in the 1:2 propensity score-matched macrolide maintenance therapy (MMT) receivers versus macrolide non-receivers. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; AMI: acute myocardial infarction.

Regarding the secondary outcomes, MMT receivers exhibited a significantly reduced risk of AMI (5.33 versus 10.28 events per 1000 person-years; HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.33–0.83) and all-cause mortality (109.95 versus 132.04 events per 1000 person-years; HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74–0.93) compared with macrolide non-receivers. The incidence rates of cardiovascular death and stroke were also lower in MMT receivers compared with macrolide non-receivers (cardiovascular death: 6.47 versus 7.52 events per 1000 person-years; stroke: 7.46 versus 11.15 events per 1000 person-years), although the difference did not reach a statistical significance (figure 1). The Kaplan–Meier curve depicting the cumulative incidence of MACE was consistent with the results obtained from the Cox regression analysis (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in the propensity score-matched cohort. MMT: macrolide maintenance therapy.

Safety outcome analysis

A total of 31 ventricular arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death events occurred among MMT receivers, while 55 events occurred among macrolide non-receivers (7.17 versus 7.67 events per 1000 person-years). The use of MMT was thus not associated with increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.60–1.44) (figure 1).

Negative control outcome

Regarding the negative control outcome analysis, there were no significant differences in the risk of hip fracture hospitalisation between MMT receivers and macrolide non-receivers. The incidence rates of hip fracture hospitalisation were 6.31 and 7.46 events per 1000 person-years, respectively (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.54–1.35) (figure 1).

Exacerbation incidence analysis

In the PS-matched cohort, MMT receivers and macrolide non-receivers experienced a mean±sd 0.43±0.91 and 0.60±1.20 exacerbations per person, separately, within 6 months after the index date, indicating a 33% relative reduction associated with MMT (incidence rate ratio 0.67, 95% CI 0.60–0.74) (supplementary table S3). Among the study population, 288 (25.65%) MMT receivers and 679 (33.71%) macrolide non-receivers experienced at least one exacerbation within 6 months after the index date, respectively, suggesting a 40% relatively lower risk (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.49–0.72) (supplementary table S4). Exacerbation incidence rates preceding and after the index date stratified by exposure group are illustrated in supplementary figure S4.

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

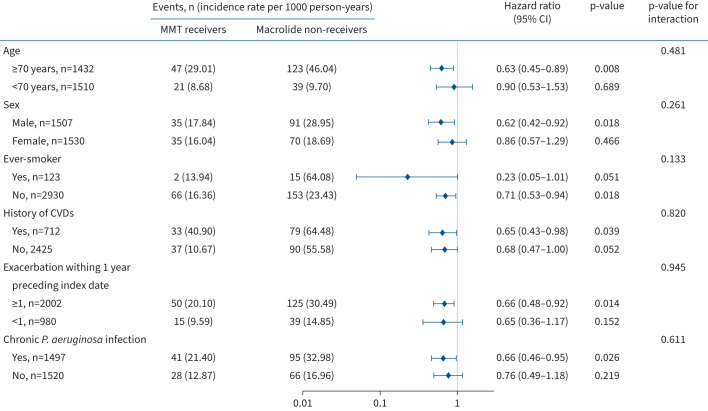

The association between MMT and MACE was similar by age, sex, smoking history, cardiovascular diseases, 1-year exacerbation frequency preceding enrolment and chronic P. aeruginosa infection. However, it is important to note that the precision of the estimate might have been limited due to the small number of patients included in the subgroup analysis. Specifically, statistical significance was not reached in subgroups of patients aged <70 years, females and patients with a smoking history. These subgroup analysis results are considered exploratory and should be interpreted with caution (figure 3 and supplementary figure S5).

FIGURE 3.

Primary outcome in propensity score-matched macrolide maintenance therapy (MMT) receivers versus macrolide non-receivers by various subgroups. CVD: cardiovascular disease; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa. History of CVDs was defined as history of acute myocardial infraction, stroke, unstable angina hospitalisation, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting, peripheral artery diseases, congestive heart failure, or arrythmia.

The robustness of our findings was further confirmed through additional analyses. Results remained consistent when inverse probability of treatment weighting and doubly robust models were used for covariate adjustment. Moreover, the prescription time-distribution matching model yielded similar findings, which effectively addressed the concern regarding immortal time bias. Furthermore, the association between MMT and MACE incidence reduction remained statistically significant when we excluded patients who had a history of non-tuberculous mycobacteria infection and ventricular arrhythmias (supplementary table S5). As shown in supplementary table S6, there was no significant association between MMT administration and AMI or stroke incident within 1 year preceding enrolment.

Exploratory analysis

MMT was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of MACE compared with non-maintenance macrolide therapy (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.47–0.81). However, non-maintenance macrolide therapy did not appear to lower the risk of MACE when compared with macrolide non-receivers (HR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99–1.21). Furthermore, we found no additional benefits from prolonged MMT compared with the standard MMT regimen (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.36–1.09) (supplementary table S7).

Discussion

In this territory-wide cohort study involving patients with bronchiectasis, MMT was associated with a 32% risk reduction in MACE, while not associated with increased risk of ventricular arrythmia or sudden cardiac death. The therapeutic effect of MMT was found to be dependent on a minimum effective dosage and duration, as extending the duration did not lead to additional benefits. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation to examine the relationship between MMT and cardiovascular adverse outcomes, and to evaluate its cardiovascular safety profile specifically in patients with bronchiectasis.

MMT has been recommended for adults with bronchiectasis due to the high-quality evidence on exacerbation reduction [7, 14–16]. Here we observed 33% reduction in exacerbation frequency associated with MMT, supporting the real-world efficacy of these treatments for people living with bronchiectasis. Importantly, we also observed a significant association between MMT use and decreased incidence of cardiovascular events. Exacerbation has been recognised as a major risk factor for the high prevalence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with bronchiectasis, independent of advanced age, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes [5, 6, 18]. The systemic inflammatory response induced by a bronchiectasis exacerbation is hypothesised to trigger plaque rupture, microthrombosis and ultimately cardiovascular damage [19, 20]. Macrolides, when administered over a prolonged period, have immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory effects that extend beyond their antibacterial properties [21]. For example, long-term azithromycin and erythromycin treatment significantly reduced serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels compared with placebo in the EMBRACE and Bronchiectasis and Low-dose Erythromycin Study (BLESS) trials [15, 16]. Animal studies have further demonstrated the myocardial protective effect of macrolide antibiotics following AMI and their neuroprotective effect following ischaemic stroke, mainly through promoting the transformation of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory phenotype to an anti-inflammatory phenotype [22, 23]. These observations served as the impetus for our study and rationalise our findings on the possible protective benefits of long-term macrolide use in reducing cardiovascular adverse events among bronchiectasis patients.

While our findings indicate that macrolides could potentially offer cardiovascular protection, it is worth noting that some other studies have not yielded similar results. The Azithromycin in Acute Coronary Syndrome (AZACS) study [24], the Weekly Intervention with Zithromax for Atherosclerosis and its Related Disorders (WIZARD) study [25] and the Azithromycin and Coronary Events Study (ACES) [26] reported that azithromycin provided a neutral effect in the secondary prevention of atherosclerosis cardiovascular diseases (ASCVDs). Several factors may contribute to the discrepancy between our findings and the results observed in these previous trials. First, the aforementioned studies did not encompass individuals with chronic lung disease and were instead “all-comers” at risk of cardiovascular disease. Second, the duration of azithromycin treatment in these trials was notably shorter than the MMT protocol employed in our investigation (5 days in AZACS and 11 weeks in WIZARD). In ACES, although the azithromycin treatment lasted for 1 year, the frequency of prescription, with azithromycin administered once weekly, remained lower than that of our study cohort. Lastly, it is important to note that the design of these studies was based on the hypothesis that Chlamydia pneumoniae, an organism susceptible to azithromycin, was one of the culprits in ASCVD development and that macrolides prevented cardiovascular events through averting C. pneumoniae infection. Unlike the clear and robust relationship between bronchiectasis exacerbation and cardiovascular diseases, the association between C. pneumoniae and cardiovascular diseases remains somewhat unclear and there is a lack of consolidated evidence in the published literature [27–29].

The results of our safety outcome analysis favoured the prescription of MMT in patients with bronchiectasis, supporting the notion that MMT may be cardioprotective in people with chronic lung disease, in keeping with prior work from our group in those living with COPD [30, 31]. In clinical practice, ventricular arrythmia or sudden cardiac death associated with macrolide antibiotics have been topics of concern, although the evidence has been conflicting. For instance, Ray et al. [9, 32] reported increased risk of sudden cardiac death associated with erythromycin and azithromycin in 2004 and 2012, respectively. However, a subsequent Danish cohort study did not observe any substantial increase in the risk of cardiovascular death among azithromycin users [33]. Additionally, a large multicentre nested case–control study reported no significant difference in ventricular arrhythmia risk between azithromycin users and amoxicillin users [34]. It is important to note that these studies focused on acute courses of macrolides; as such, a common limitation of these studies was the inability to fully elucidate the impact of confounding by indication, such as the site of infection, pathogen and disease severity, which may have led to an unequal distribution of the risk of acute cardiovascular events between macrolide receivers and the control groups, even after adjusting for coexisting heart diseases and other known cardiovascular risk factors. This limitation may have led to the marked heterogeneity across different studies, thereby limiting the generalisability of the findings [35]. In contrast, our research focused on evaluating the cardiovascular safety profile specifically in bronchiectasis patients, providing more targeted and generalisable insights for this patient population.

Clinical implication

Our study provides the first real-world evidence to suggest that MMT was associated with reduced incidence of MACE in patients with bronchiectasis, while also demonstrating a favourable cardiovascular safety profile. Our study findings suggest MMT in patients with bronchiectasis may serve a dual purpose, not only reducing exacerbations but also exerting a cardiovascular protective effect, and this warrants further evaluation in prospective clinical trials.

Strength and limitations

The strength of our study included the use of CDARS, a well-validated electronic healthcare database with comprehensive records of all diagnoses, hospitalisations and details of drug dispenses for the entire population of Hong Kong. By utilising this database, we were able to collect relevant information in a standardised and objective manner, thereby minimising the potential for common biases that can arise in conventional observational studies, such as selection and recall biases. Moreover, the application of the PS matching method enabled us to balance the distribution of confounding variables between treatment groups, thus improving the validity of the results. Lastly, the sensitivity analysis adopting different models further validated our study results.

Our study has several limitations. First, we were unable to thoroughly evaluate bronchiectasis severity due to limited access to radiological and lung function data. Nevertheless, we addressed this limitation by adjusting for exacerbation incidence, a key indicator of disease severity [2]. Second, missing laboratory results (e.g. CRP and interleukin) hindered exploring potential mechanisms for MMT's cardiovascular benefits. Third, the retrospective nature of our study limited our ability to establish a causal relationship between the prevention of exacerbations through MMT and the protective effect on cardiovascular outcomes. Prospective studies are warranted to test this hypothesis in the future. Fourth, a major concern is that of indication bias where clinicians withhold MMT in a subset of patients deemed more likely to be at risk of MACE. We addressed this concern by adjusting for cardiovascular comorbidities, and the sensitivity analysis excluding patients with a history of ventricular arrhythmias further enhanced the validity and robustness of our findings. Importantly, there was no difference between groups for MACE incidence in the year prior to enrolment. Lastly, as an observational study, there is a possibility of residual confounding factors that may not have been completely adjusted. Reassuringly, our analysis using a negative control outcome, i.e. hip fracture hospitalisation, yielded null results.

Conclusions

In this territory-wide cohort of patients with bronchiectasis, MMT was associated with a significantly reduced risk of MACE, with no indication of an elevated risk of severe arrythmia-related side-effects. These results suggest arrhythmogenic concerns related to MMT may be overstated and the potential cardiovascular protective effect of MMT in patients with bronchiectasis merits evaluation by a future randomised study.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-01574-2024.Supplement (960.5KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgement

We thank the Hong Kong Hospital Authority for granting access to the data.

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and the West Cluster of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority. Informed patient consent was not required as the data used in this study were anonymised.

Author contributions: F. Frost, D. Wat, S.H.M. Lam, G.Y.H. Lip and K-H. Yiu were responsible for the study design. R. Guo completed the initial data preparation and statistical analyses. R. Guo and K-H. Yiu drafted the manuscript. A-P. Cai, Y-H. Chan, Q-W. Ren, J-Y. Huang, J-N. Zhang, W-L. Gu, C.T-W. Tsang, C-Y. Zhu and Y-M. Hung contributed to the statistical analyses. T. Bucci, F. Frost, G.Y.H. Lip and K-H. Yiu provided the clinical expertise. All authors critically reviewed and contributed to the intellectual content of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. R. Guo and K-H. Yiu are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have approved the final manuscript for publication.

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00045-2025

Conflict of interest: D. Wat has received speaker's fees from Chiesi, AstraZeneca, GSK, Sterling Anglian, Glenmark and Insmed. F. Frost has received speaker's fees from Chiesi, AstraZeneca and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and support for attending meetings and travel from Chiesi. The research presented in this manuscript was conducted independently, and the authors declare that there was no impact of the conflicts of interest on the work. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Support statement: This study was supported by the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen, China (SZSM201911020) and supported by HKU-SZH Fund for Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline (SZXK2020081). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Navaratnam V, Millett ER, Hurst JR, et al. Bronchiectasis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Thorax 2017; 72: 161–166. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, et al. The bronchiectasis severity index. An international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 576–585. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1575OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost F, Lip GYH. Cardiorespiratory multimorbidity in people living with chronic lung disease: challenges, opportunities, and a concept for optimization via an integrated care approach. Chest 2024; 165: 500–502. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalmers JD. Bronchiectasis exacerbations are heart-breaking. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 301–303. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201710-832ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendez R, Feced L, Alcaraz-Serrano V, et al. Cardiovascular events during and after bronchiectasis exacerbations and long-term mortality. Chest 2022; 161: 629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saleh AD, Kwok B, Brown JS, et al. Correlates and assessment of excess cardiovascular risk in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1701127. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01127-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700629. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assimon MM, Pun PH, Wang L, et al. Azithromycin use increases the risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with hemodialysis-dependent kidney failure. Kidney Int 2022; 102: 894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1881–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng YJ, Nie XY, Chen XM, et al. The role of macrolide antibiotics in increasing cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66: 2173–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwok WC, Tam TCC, Sing CW, et al. Validation of diagnostic coding for bronchiectasis in an electronic health record system in Hong Kong. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2023; 32: 1077–1082. doi: 10.1002/pds.5638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai Y, Luo H, Wong GHY, et al. Risk of self-harm after the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in Hong Kong, 2000–10: a nested case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: 135–147. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren QW, Yu SY, Teng TK, et al. Statin associated lower cancer risk and related mortality in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 3049–3059. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altenburg J, de Graaff CS, Stienstra Y, et al. Effect of azithromycin maintenance treatment on infectious exacerbations among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the BAT randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 1251–1259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serisier DJ, Martin ML, McGuckin MA, et al. Effect of long-term, low-dose erythromycin on pulmonary exacerbations among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the BLESS randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 1260–1267. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong C, Jayaram L, Karalus N, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (EMBRACE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 660–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60953-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohanty A, Tate JP, Garcia-Tsao G. Statins are associated with a decreased risk of decompensation and death in veterans with hepatitis C-related compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 430–440. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Garcia MA, Bekki A, Beaupertuy T, et al. Is bronchiectasis associated with cardiovascular disease? Respir Med Res 2022; 81: 100912. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2022.100912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazaz R, Marriott HM, Francis SE, et al. Mechanistic links between acute respiratory tract infections and acute coronary syndromes. J Infect 2013; 66: 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maclay JD, McAllister DA, Johnston S, et al. Increased platelet activation in patients with stable and acute exacerbation of COPD. Thorax 2011; 66: 769–774. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.157529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venditto VJ, Feola DJ. Delivering macrolide antibiotics to heal a broken heart – and other inflammatory conditions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2022; 184: 114252. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Darraji A, Haydar D, Chelvarajan L, et al. Azithromycin therapy reduces cardiac inflammation and mitigates adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction: potential therapeutic targets in ischemic heart disease. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0200474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amantea D, Certo M, Petrelli F, et al. Azithromycin protects mice against ischemic stroke injury by promoting macrophage transition towards M2 phenotype. Exp Neurol 2016; 275: 116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cercek B, Shah PK, Noc M, et al. Effect of short-term treatment with azithromycin on recurrent ischaemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the Azithromycin in Acute Coronary Syndrome (AZACS) trial: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 361: 809–813. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor CM, Dunne MW, Pfeffer MA, et al. Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease events: the WIZARD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290: 1459–1466. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grayston JT, Kronmal RA, Jackson LA, et al. Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary events. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1637–1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Younes HM, Abu Abeeleh MA, Jaber BM. Lack of strong association of Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis in a Jordanian population. J Infect Dev Ctries 2016; 10: 457–464. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danesh J, Whincup P, Walker M, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG titres and coronary heart disease: prospective study and meta-analysis. BMJ 2000; 321: 208–213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7255.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danesh J, Whincup P, Lewington S, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA titres and coronary heart disease; prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2002; 23: 371–375. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bucci T, Wat D, Nazareth D, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events after acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients receiving long-term low-dose azithromycin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024; 209: 1394–1396. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202309-1699LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bucci T, Wat D, Sibley S, et al. Low-dose azithromycin prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Emerg Med 2024; 19: 1615–1623. doi: 10.1007/s11739-024-03653-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray WA, Murray KT, Meredith S, et al. Oral erythromycin and the risk of sudden death from cardiac causes. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1089–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svanstrom H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1704–1712. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trifiro G, de Ridder M, Sultana J, et al. Use of azithromycin and risk of ventricular arrhythmia. CMAJ 2017; 189: E560–E568. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorelik E, Masarwa R, Perlman A, et al. Systematic review, meta-analysis, and network meta-analysis of the cardiovascular safety of macrolides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e00438-18. doi: 10.1128/aac.00438-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-01574-2024.Supplement (960.5KB, pdf)

This PDF extract can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-01574-2024.Shareable (724.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.