Abstract

Background:

The World Health Organization recommends that all postpartum women be examined for resumed sexual activity. Despite this, postpartum sexual health education and health promotion are not adequately incorporated into current maternal healthcare systems in low- and middle-income nations. There were variations in the prevalence and variables associated with early postpartum sexual intercourse across several studies.

Objectives:

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the pooled prevalence and associated factors for early postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan African countries.

Data Sources and Methods:

Primary studies were identified using international databases such as Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, and CINAHL. The Newcastle‒Ottawa Scale quality assessment tool was used to evaluate the quality and strength of the included studies. STATA version 17 was used for the meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of the studies and publication bias was examined using I2 statistics and Egger’s regression test. Subgroup analysis decreased the underlying heterogeneity based on the study years and sample sizes.

Results:

Seventeen primary articles were included in the meta-analysis with 8507 study participants. The pooled prevalence of early postpartum sexual resumption in sub-Saharan Africa was 39.41% (95% CI: 31.55%–47.27%). Primiparous (OR = 3.32; 95% CI: 2.26–5.90), spontaneous vaginal delivery (OR = 5.98; 95% CI: 1.74–20.51), formula feeding (OR = 2.24; 95% CI: 1.46–3.44), family planning (OR = 2.91; 95% CI: 1.89–4.49), husband pressure (OR = 4.99; 95% CI: 1.38–18.05), have no formal education (OR = 2.36; 95% CI: 1.49–3.76), and monogamy (OR = 4.18; 95% CI: 2.27–7.69) were significantly associated with early postpartum sexual resumption.

Conclusion:

Four out of 10 women had returned to sexual activity within 6 weeks of giving birth. This suggests that a large proportion of women are more vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies and sexual health problems. Sexual health education and counseling should be incorporated into standard postpartum care to increase contraceptive use and delay unplanned pregnancies.

Keywords: early sexual resumption, sexual intercourse, postpartum, 6 weeks of childbirth, sub-Saharan Africa

Plain language summary

Early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa

The return of sexual intercourse after delivery, as well as the use of contraceptive measures, are key parts of postpartum sexual health. Postpartum sexual health has received little attention from researchers and clinicians, with the focus remaining exclusively on postpartum contraception. Sexual health care should be integrated into primary care, and sexual health education and counseling should be offered as part of routine postpartum care. Healthcare providers place more of a focus on suggestions related to contraception because they expect that women would regain normal sexual function after giving birth and would not bother to provide counseling on postpartum sexual activity. Clinicians have paid little attention to postpartum sexual health, and the prevalence and factors associated with early postpartum sexual intercourse have been inconsistent. The goal of this study was to determine the pooled prevalence and associated factors of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

Postpartum sexual health is gaining popularity around the world, and early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse might hamper postpartum health.1,2 Resumption of sexual intercourse after delivery and the use of contraceptive measures are integral aspects of postpartum sexual health.1,3

Engaging in sexual intercourse during the early postpartum period is often associated with reproductive tract infections and unintended pregnancy. 4 After childbirth, hormonal changes can lead to vaginal tissue contracting and becoming more sensitive. It’s important for the vagina, uterus, and cervix to return to their normal size for healthy sexual intercourse. 5 Engaging in sexual intercourse soon after childbirth raises the risk of infections caused by vaginal sores and abrasions. 6 Many mothers who resumed sexual activity within the first 3 months after childbirth reported experiencing various sexual health issues, such as pain during intercourse, insufficient vaginal lubrication, difficulty achieving orgasm, vaginal laxity, reduced sexual desire, abnormal vaginal discharge, and genital tears.7,8

The recommendation for when it is safe to engage in sexual intercourse after giving birth largely depends on the mode of delivery. In general, advice suggests waiting for at least 6 weeks after childbirth before resuming postpartum sexual intercourse. 9 The World Health Organization identifies postpartum sexual health as one of the most critical concerns to address during the postpartum period. 2 Even though most maternal deaths and complications occur during this time, postpartum mothers receive considerably less attention and care compared to pregnant and laboring women. 10 Unfortunately, postpartum sexual health has received limited attention from researchers and clinicians, who have predominantly focused on postpartum contraception. 11

Sexual healthcare should be integrated into primary care, and sexual health education and counseling should be offered as part of routine postpartum care. 12 Postpartum education regarding sexual behavior and contraceptives can improve the effective use of contraceptives and delay the onset of sexual activity.13,14 Healthcare providers often focus more on suggestions related to contraception because they expect women to regain normal sexual function after giving birth and therefore may not provide counseling on postpartum sexual activity. 10

The prevalence and factors associated with early postpartum sexual intercourse have been inconsistent. Previous studies reported varying rates of early resumption of sexual intercourse, ranging from 20.2% in Ethiopia 15 to 79.1% in Cameroon. 16 The goal of this study was to determine the pooled prevalence and associated factors of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa. The study results will help clinicians and policymakers design effective interventions to improve the standard of postpartum care by integrating family planning and sexual health education into postnatal care.

Methods

The review process was established using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplemental File 1). 17

Population

Women of reproductive age group and post-partum women

Exposure

Factors influencing the early resumption of sexual intercourse among postpartum women include socio-demographic variables, parity, and mode of delivery, genital injury during birth, contraceptive use, and partner pressure to have sex.

Outcome measurements

This review and meta-analysis had two main outcomes. The primary outcome was the prevalence of early resumption of sexual intercourse among postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa. The second outcome was factors associated with the early resumption of sexual intercourse among postpartum women.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies published between 2010 and 2023 on the early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa were reviewed. Studies that did not include at least one factor or the prevalence of sexual activity within the first 6 weeks after delivery were omitted. Interventional studies, case reports, systematic reviews, qualitative articles, case series, conference abstracts, letters to the editor, newspaper articles, and other types of popular media were also excluded.

Data sources and search strategy

We used electronic databases to retrieve studies for this review and meta-analysis from Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, and CINAHL. The search terms used were as follows: postpartum period, postpartum women, puerperium, sexual intercourse, coitus, early resumed sexual intercourse, associated factors, risk factors, associated risk factors, determinants, and sub-Saharan Africa. Our search strategy included key terms and phrases such as “postpartum period”[MeSH Terms] OR (“postpartum”[All Fields] AND “period”[All Fields]) OR “postpartum period”[All Fields] OR (“postpartum period”[MeSH Terms] OR (“postpartum”[All Fields] AND “period”[All Fields]) OR “postpartum period”[All Fields] OR “postpartum”[All Fields]) OR “Postpartum Women”[All Fields] OR (“postpartum period”[MeSH Terms] OR (“postpartum”[All Fields] AND “period”[All Fields]) OR “postpartum period”[All Fields] OR “puerperium”[All Fields]) AND “coitus”[MeSH Terms] OR “coitus”[All Fields] OR “Coital Frequency”[All Fields] OR “First Intercourse”[All Fields] OR “Sexual Intercourse”[All Fields] AND “Associated factors” OR “risk factors” OR “associated risk factors” OR “determinants” AND “africa south of the sahara”[MeSH Terms] OR (“africa”[All Fields] AND “south”[All Fields] AND “sahara”[All Fields]) OR “africa south of the sahara”[All Fields] OR “africa sub Saharan”[All Fields] OR “Sub-Saharan Africa”[All Fields] OR “Sub-saharan Africa”[All Fields] (Supplemental File 2).

Study selection

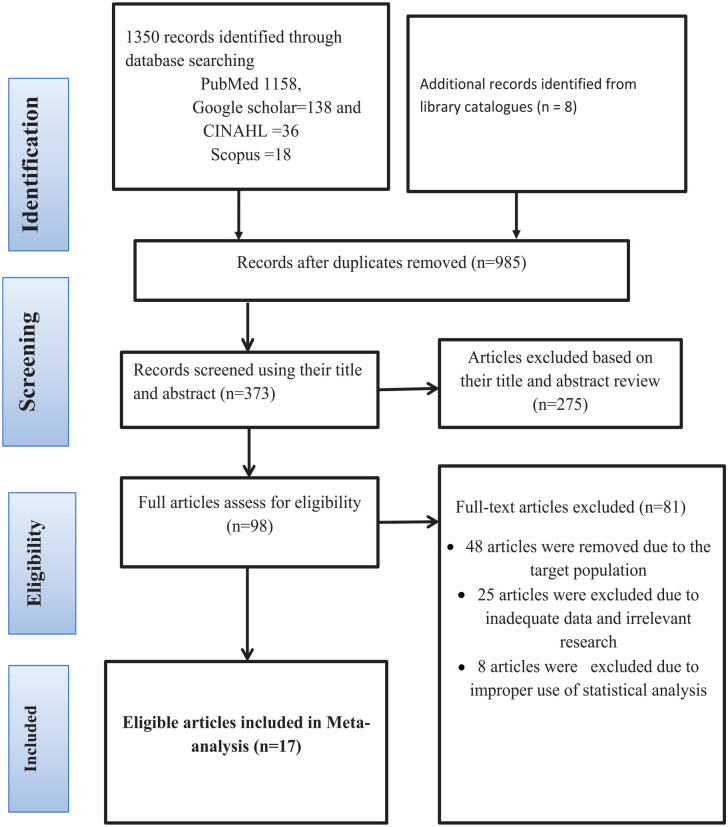

An electronic database was used to search 1358 primary studies. The search results were initially downloaded into Endnote version IX, and duplicates were removed. The studies were carried out in two stages. The complete text was evaluated once the title and abstract were screened. After screening the title and abstract, the full text was reviewed. A total of 989 articles were excluded due to duplication. Additionally, 275 articles were excluded after evaluating their titles and abstracts, while 81 articles were excluded because of issues related to the target population, insufficient data, inappropriate study design, or improper statistical analysis. Three independent reviewers assessed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies. Potentially relevant papers were selected for full-text review, and 17 publications were ultimately included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Disagreements among reviewers were resolved using predefined article selection criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart for the study selection process.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data were extracted by four independent reviewers using a standardized data extraction form. This tool included fields for the primary author’s name, year of publication, study setting, sample size, study methodology, and the prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse. Any uncertainties during the extraction process were addressed by involving the fifth and sixth authors. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale quality evaluation instrument was used to assess the quality and strength of the included studies. 18 Three reviewers (HGB, MDW, and GNM) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. Articles with a mean quality score of ⩾6 out of 9 were included in the analysis. Fifteen cross-sectional and two cohort study articles met the quality criteria (Supplemental File 3).

Meta-analysis

The extracted data were entered into Microsoft Excel and then exported to STATA version 17 software for further analysis. 19 We included at least two studies that reported one factor associated with early postpartum sexual intercourse, along with their measure of effect and 95% confidence interval (CI). A random-effects model, based on the DerSimonian–Laird method, was used to assess variations between the studies.

Publication bias and heterogeneity

The I 2 test statistic was used to examine the heterogeneity of the included studies. Heterogeneity was declared as p ⩽ 0.05. 20 Egger’s test was used to determine the statistical significance of publication bias, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. 21

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

There were 15 cross-sectional studies and 2 cohort studies. Five of the reviewed articles (29.4%) were from Ethiopia, 7 (41.2%) were from Nigeria, 3 (17.6%) were from Uganda, 1 (5.9%) was from Cameron, and one study (5.9%) was from Ghana. The sample size ranged from 120 in Cameroon 16 to 1980 in Ghana. 22 The prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa in the included studies was between 20.2% in Ethiopia and 79.1% 15 in Cameroon (Table 1). 16

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 17 studies included in the meta-analysis of the early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan African countries, 2023.

| Author (year) | Countries | Study setting and study design | Sample size | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jambola et al. (2020) | Ethiopia | Facility-based cross-sectional study | 528 | 20.2 |

| Gadisa et al. (2021) | Ethiopia | Facility-based cross-sectional study | 330 | 59.3 |

| Mekonnen (2020) | Ethiopia | A community based cross-sectional study | 634 | 26.9 |

| Edosa Dirirsa et al. (2022) | Ethiopia | Facility-based cross-sectional study | 421 | 31.6 |

| Tesfay F et al. (2018) | Ethiopia | Facility-based cross-sectional study | 445 | 73.4 |

| Owonikoko KM et al. (2014) | Nigeria | Facility-based cross-sectional study | 400 | 35.8 |

| Anzaku AS et al. (2014) | Nigeria | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 352 | 67.7 |

| Adanikin et al. (2015) | Nigeria | Prospective cohort study | 203 | 27.6 |

| Oke et al. (2022) | Nigeria | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 366 | 37.6 |

| Ezebialu IU et al. (2012) | Nigeria | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 680 | 29.7 |

| Iliyasu et al. (2018) | Nigeria | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 371 | 21.7 |

| Adenike OB et al. (2017) | Nigeria | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 460 | 38.9 |

| Alum et al. (2015) | Uganda | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 374 | 21.9 |

| Kaye DK et al. (2011) | Uganda | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 131 | 58 |

| Madenje M et al. (2020) | Uganda | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 622 | 25 |

| Nkwabong et al. (2019) | Cameroon | Retrospective cohort | 120 | 79.1 |

| Eliason et al. (2017) | Ghana | Facility-based cross-sectional study sexual | 1980 | 23.9 |

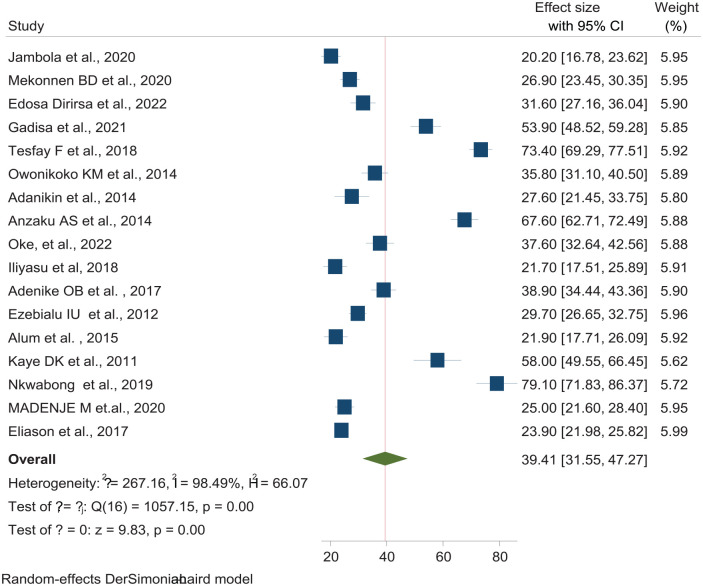

Early resumption of the postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa

A random effect meta-analysis model was employed. The overall pooled estimate of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa was 39.41% (95% CI: 31.55%–47.27%); I 2 = 98.49%, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the pooled prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in Sub-Saharan African countries.

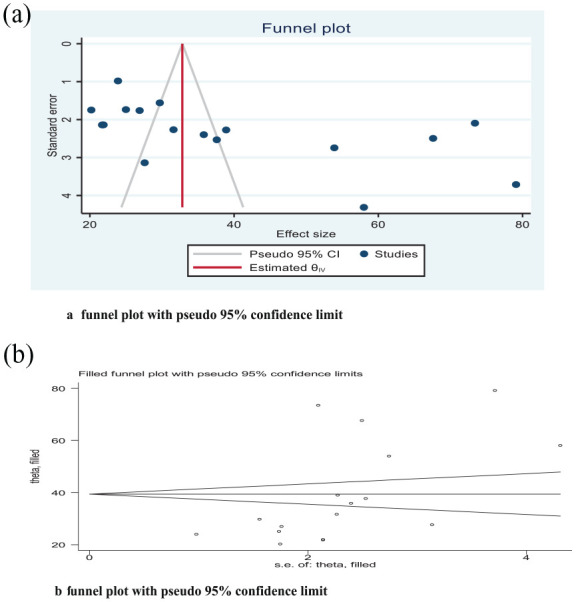

Heterogeneity and publication bias

The findings of this study indicated significant heterogeneity across the studies, as shown by the I² statistic (I² = 98.49%, p ⩽ 0.001). A funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were used to assess publication bias. The funnel plot revealed an asymmetrical distribution (Figure 3A). The p-value for Egger’s regression test was 0.016, indicating the presence of publication bias (Table 2). Duval and Tweedie’s nonparametric trim-and-fill analysis was employed to address publication bias in the 17 studies that examined the early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa. However, the analysis did not identify any missing studies to be imputed (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(a) Funnel plots to test publication bias in 17 studies. (b) No additional studies were added to the trim and fill analysis to correct publication bias.

Table 2.

Egger’s regression test.

| Egger’s test | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | p > t | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | 8.177247 | 9.633802 | 0.85 | 0.409 | −12.35672–28.71121 |

| Bias | 13.25003 | 4.866237 | 2.72 | 0.016 | 2.877891–23.62217 |

CI: Confidence interval.

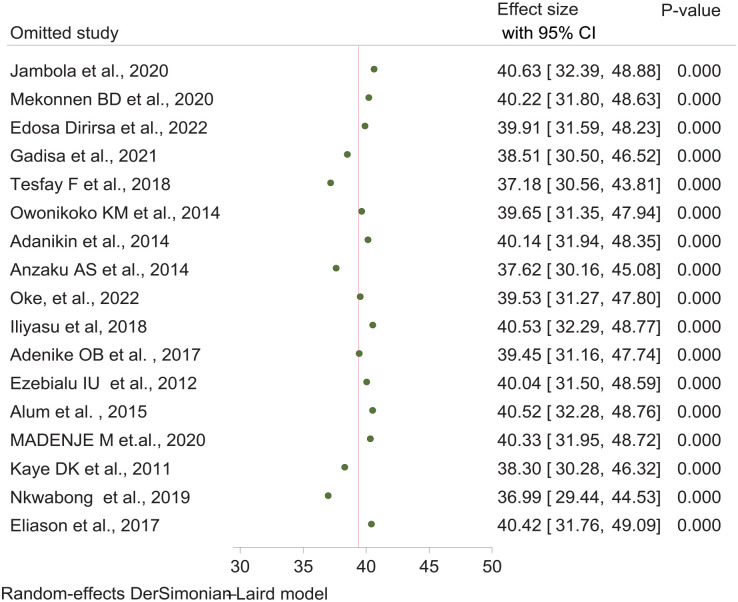

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a random-effects model to identify outliers and assess the impact of individual studies on the overall meta-analysis outcome. We performed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. The results indicated that no single study significantly influenced the overall outcome. The pooled prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa varied, ranging from 36.99% (95% CI: 29.44%–44.53%) to 40.63% (95% CI: 32.39%–48.88%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analyses for the prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan African countries, 2023.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on country, study design, sample size, and study year to identify sources of heterogeneity. Ethiopia had the highest pooled prevalence of early resumption of sexual intercourse within 6 weeks postpartum at 41.17% (95% CI: 21.56%–60.77%), while Uganda had the lowest prevalence at 34.34% (95% CI: 9.33%–49.36%). In the subgroup analysis based on the study year, the pooled incidence was 39.96% (95% CI: 26.22%–53.71%) for studies conducted between 2010 and 2015, and 39.13% (95% CI: 29.01%–49.25%) for studies conducted between 2016 and 2023. The pooled prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse, based on subgroup analysis by sample size, was 45.81% (95% CI: 30.93%–60.70%) for studies with sample sizes less than 400, and 33.88% (95% CI: 24.67%–43.10%) for studies with sample sizes of 400 or more. The highest pooled prevalence was observed in studies with a cohort design, at 53.31% (95% CI: 2.84%–103.78%), while cross-sectional studies had a prevalence of 37.61% (95% CI: 29.71%–45.50%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse based on the country, study design, and sample size and study year.

| Sub group | Number of studies | Random effects (95% CI) | Test of heterogeneity I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | |||

| Ethiopia | 5 | 41.17 (21.56–60.77) | 99.15 |

| Nigeria | 7 | 36.97 (26.57–47.37) | 97.39 |

| Uganda | 3 | 34.34 (19.33–49.36) | 96.59 |

| Study design | |||

| Crosse-sectional | 15 | 37.61 (29.71–45.50) | 98.44 |

| Cohort | 2 | 53.31 (2.84–103.78) | 99.11 |

| Sample size | |||

| <400 | 8 | 45.81 (30.93–60.70) | 98.40 |

| ⩾400 | 9 | 33.88 (24.76–43.10) | 98.50 |

| Publication year | |||

| 2010–2015 | 6 | 39.96 (26.27–53.71) | 98.03 |

| 2016–2023 | 11 | 39.13 (29.01–49.25) | 98.74 |

CI: confidence interval.

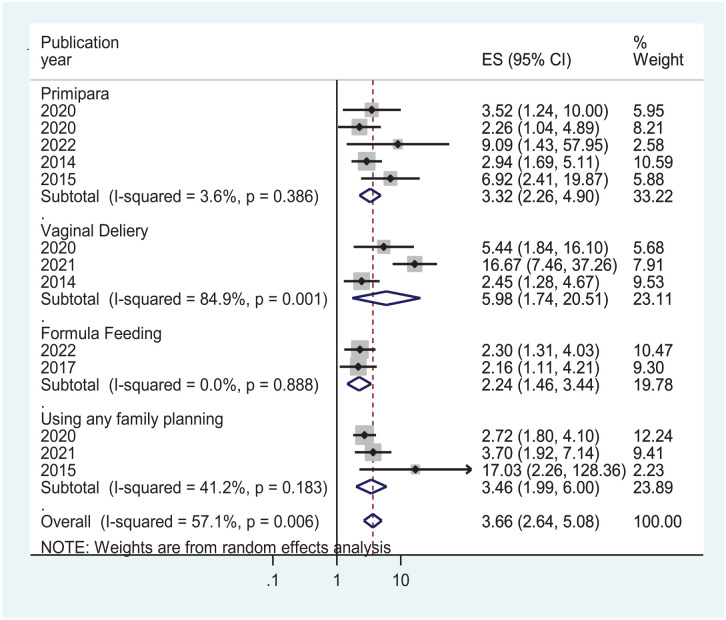

Factors associated with early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse

The pooled effect of five studies15,23 –26 indicated that being primiparous was statistically associated with early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse. Primiparous mothers had a threefold greater risk of resuming sexual intercourse before the 6-week postpartum period compared to multiparous mothers (OR = 3.32; 95% CI: 2.26–5.90) (Figure 5). The pooled effect of three studies15,27,28 indicated that normal vaginal delivery significantly increased the risk of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse by nearly six times compared to complicated vaginal delivery and cesarean section (OR = 5.98; 95% CI: 1.74–20.51) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot for the pooled effect of primiparous, normal vaginal delivery, formula feeding, and family planning with early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan African countries, 2023.

The pooled effect of two studies22,24 showed that formula feeding increased the risk of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse twofold compared to breastfeeding mothers (OR = 2.24; 95% CI: 1.46–3.44) (Figure 5). Four reviewed studies23,25,27,29 indicated that using family planning methods increased the risk of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse by nearly three times compared to not using family planning methods (OR = 2.91; 95% CI: 1.89–4.49) (Figure 5).

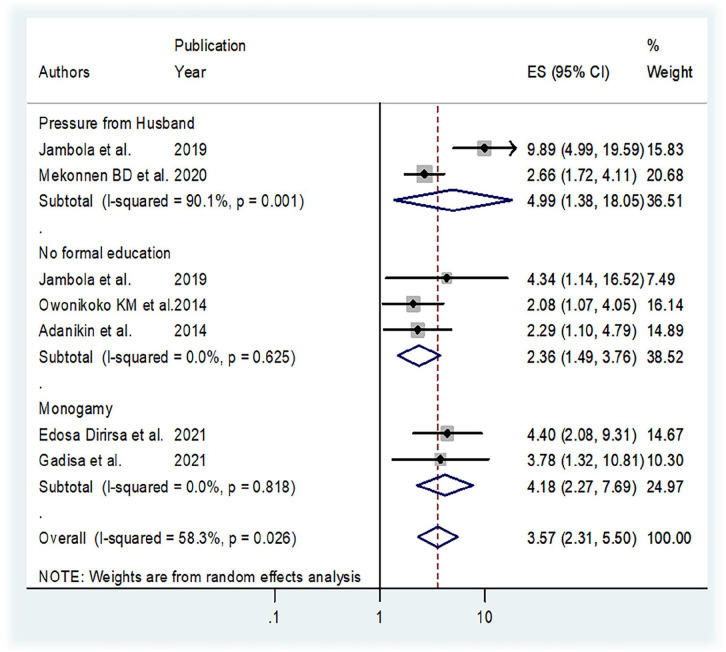

Two primary studies reviewed15,23 found that pressure from husbands to engage in sexual intercourse increased the risk of early resumption of postpartum sexual activity by nearly fivefold (OR = 4.99; 95% CI: 1.38–18.05) (Figure 6). Three studies reviewed15,26,28 showed that mothers with have no formal education had twice the risk of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse compared to mothers with formal education (OR = 2.36; 95% CI: 1.49–3.76) (Figure 6). The pooled results of two independent studies24,27 showed that being in a monogamous relationship increased the risk of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse twofold compared to other relationship types (OR = 4.18; 95% CI: 2.27–7.69) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot for the pooled effect of pressure from husbands, mothers with no formal education, and monogamous parents with early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan African countries, 2023.

Discussion

The goal of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to metasynthesized the prevalence and determinant factors of early postpartum sexual resumption before 6 weeks postpartum in sub-Saharan African countries. According to this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa was 39.41% (95% CI: 31.55%–47.27%). Even though more than 90% of women worldwide prefer to postpone or avoid future pregnancies, they frequently continue sexual activity without utilizing family planning methods. 30 This finding is consistent with findings from the United States 43% 31 and China 36%. 32 This finding is lower than the findings of a multilevel analysis of Demographic and Health Survey Data on early sexual resumption among postpartum women in Sub-Saharan Africa, which found 67.97% (95% CI: 67.60–68.34). 33 This might be due to the fact that the Demographic and Health Survey did not show the pooled prevalence and associated factors. This finding was higher than studies from Spain, 24.4%, 34 and India, 28.3%. 35 This could be due to differences between sociocultural and healthcare systems.

In this meta-analysis, being a primiparous mother was found to be a major factor in the early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse. The majority of primiparous mothers are younger age groups who are eager to have another baby for the following period and may start sexual intercourse sooner. Supporting findings revealed that women with fewer children resume sexual activity earlier than women with many children. 36

The mode of delivery significantly affects the timing of resuming sexual intercourse within the 6-week postpartum period. According to this meta-analysis, women who had a normal vaginal delivery were nearly six times more likely to engage in sexual intercourse during this period compared to those who experienced complicated vaginal deliveries or cesarean sections. Several studies have shown that women who underwent episiotomies, experienced perineal tears, or had instrumental deliveries were notably less likely to resume sexual intercourse within 6 weeks postpartum compared to those who had spontaneous vaginal birth.37,38 The rationale could be that the recovery time following a cesarean section may be longer than for a vaginal delivery because women may experience more pain and discomfort in their abdomen while the skin and nerves surrounding their surgical scar heal slowly.

Women who were not breastfeeding were twice as likely to resume sexual intercourse before 6 weeks postpartum. This study’s findings are consistent with research indicating that breastfeeding reduces levels of progesterone, estrogen, and androgen. These hormonal changes may indirectly affect sexual interest by increasing breast sensitivity, reducing sexual desire, decreasing vaginal lubrication, and causing vaginal atrophy. 39 Breastfeeding emerged as the main predictor of dyspareunia during the postpartum period. Exhaustion and sleep deprivation, resulting from the need to breastfeed every few hours at night, can significantly reduce sexual desire.11,40

Utilizing any family planning methods increased the likelihood of resuming sexual activity within 6 weeks postpartum by threefold compared to those who did not use contraception. This study aligns with findings from research conducted in the United States and Poland.41,42 Women using contraception may feel less concerned about pregnancy risks, prompting them to resume sexual activity before 6 weeks postpartum. This meta-analysis found that pressure from husbands to engage in sex increased the likelihood of early resumption of sexual activity within 6 weeks postpartum by fivefold. This observation may result from gender-power dynamics, where women often encounter expectations for early sexual engagement. The current review identified that women have no formal education were twice as likely to resume sexual intercourse before the 6-week postpartum period compared to women with formal education. This could be attributed to empowered women having greater autonomy in making decisions about their sexual lives. This autonomy may reduce the influence of their partners’ sexual pressures without their consent.

This study found that women in monogamous marriages were four times more likely to resume sexual intercourse during the 6-week postpartum period compared to mothers in polygamous marriages. This difference may be attributed to the possibility that in polygamous marriages, the husband may live with his other wives until the recently postpartum wife resumes sexual intercourse. Research supports that women in polygamous marriages experience lower self-esteem and higher levels of depression and anxiety compared to women in monogamous marriages.34,43 Another study found that women who were single, divorced, or separated were more likely to delay resuming sexual intercourse compared to women living with a partner. 44

Limitations of the study

Despite the study’s strengths in integrating evidence on early resumption of sexual intercourse within the 6-week postpartum interval in sub-Saharan Africa, several limitations must be acknowledged for future research. A primary limitation was the scarcity of studies from across all Sub-Saharan African countries, with the majority originating from Uganda, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. These geographical biases could impact the generalizability of findings, and methodological biases may also affect results.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that by the 6-week postpartum period, 4 in 10 women had resumed vaginal intercourse. Factors statistically significantly associated with early resumption of sexual intercourse included prim parity, normal vaginal delivery, family planning use, formula feeding, husband’s sexual pressure, lack of formal education, and monogamous marriage.

Postnatal care will primarily focus on postpartum sexuality, pregnancy risks, and contraception. Ideally, contraceptive plans and postpartum sexual education should be established during prenatal care, and postpartum visits should be scheduled earlier than the current standard of 6 weeks.

This review will offer current information to policymakers, healthcare providers, planners, researchers, and program managers. It will also facilitate the integration of sexual healthcare into sexual health education, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing counseling as a routine component of postpartum care. Healthcare providers should pay attention to factors influencing the early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse. They should focus on identifying predictors of early resumption and educating women about initiating sexual activity while using contraception.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455057241302303 for Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Habtamu Gebrehana Belay, Enyew Dagnew Yehuala, Simegnew Asmer Getie, Alemu Degu Ayele, Tigist Seid Yimer, Besfat Berihun Erega, Wassie Yazie Ferede, Mulugeta Dile Worke and Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie in Women’s Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-whe-10.1177_17455057241302303 for Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Habtamu Gebrehana Belay, Enyew Dagnew Yehuala, Simegnew Asmer Getie, Alemu Degu Ayele, Tigist Seid Yimer, Besfat Berihun Erega, Wassie Yazie Ferede, Mulugeta Dile Worke and Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie in Women’s Health

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-3-whe-10.1177_17455057241302303 for Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Habtamu Gebrehana Belay, Enyew Dagnew Yehuala, Simegnew Asmer Getie, Alemu Degu Ayele, Tigist Seid Yimer, Besfat Berihun Erega, Wassie Yazie Ferede, Mulugeta Dile Worke and Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the authors and publishers of the original study.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Habtamu Gebrehana Belay  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1909-936X

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1909-936X

Simegnew Asmer Getie  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0748-0978

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0748-0978

Alemu Degu Ayele  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2777-4108

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2777-4108

Besfat Berihun Erega  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8075-6294

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8075-6294

Wassie Yazie Ferede  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5993-9958

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5993-9958

Mulugeta Dile Worke  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2540-9809

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2540-9809

Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1223-7980

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1223-7980

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Declaration

Ethical approval and consent to participate: This is not applicable because the study is a review, and the data used were obtained from already published materials.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contribution(s): Habtamu Gebrehana Belay: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Methodology; Validation; Writing – review & editing; Software; Formal analysis; Data curation.

Enyew Dagnew Yehuala: Writing – original draft; Methodology; Writing – review & editing; Formal analysis; Data curation.

Simegnew Asmer Getie: Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Formal analysis; Data curation.

Alemu Degu Ayele: Writing – original draft; Validation; Visualization; Methodology; Data curation.

Tigist Seid Yimer: Visualization; Validation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Software.

Besfat Berihun Erega: Software; Data curation; Writing – review & editing; Methodology; Writing – original draft.

Wassie Yazie Ferede: Validation; Writing – original draft; Formal analysis; Software; Methodology.

Mulugeta Dile Worke: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Methodology; Validation; Software; Formal analysis; Data curation.

Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie: Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Validation; Methodology; Software; Formal analysis; Data curation.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials: All the data used to support the review findings of this study are available from the manuscript.

References

- 1. O’Malley D, Higgins A, Smith V. Postpartum sexual health: a principle-based concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71: 2247–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rezaei N, Azadi A, Sayehmiri K, et al. Postpartum sexual functioning and its predicting factors among Iranian women. Malays J Med Sci 2017; 24(1): 94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chivers ML, Pittini R, Grigoriadis S, et al. The relationship between sexual functioning and depressive symptomatology in postpartum women: a pilot study. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hipp LE, Low LK, van Anders SM. Exploring women’s postpartum sexuality: social, psychological, relational, and birth-related contextual factors. J Sex Med 2012; 9(9): 2330–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baker AM, Jahn JL, Tan ASL, et al. Sexual health information sources, needs, and preferences of young adult sexual minority cisgender women and non-binary individuals assigned female at birth. Sex Res Soc Policy 2021; 18: 775–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Enderle C.d.F., da Costa Kerber NP, Lunardi VL, et al. Constraints and/or determinants of return to sexual activity in the puerperium. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2013; 21: 719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iliyasu Z, Galadanci HS, Danlami KM, et al. Correlates of postpartum sexual activity and contraceptive use in Kano, northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2018; 22(1): 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anzaku A, Mikah S. Postpartum resumption of sexual activity, sexual morbidity and use of modern contraceptives among Nigerian women in Jos. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014; 4(2): 210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mbekenga CK, Galadanci HS, Danlami KM, et al. Prolonged sexual abstinence after childbirth: gendered norms and perceived family health risks. Focus group discussions in a Tanzanian suburb. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013; 13: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clarke-Deelder E, Opondo K, Oguttu M, et al. Immediate postpartum care in low-and middle-income countries: A gap in healthcare quality research and practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023; 5(2): 100764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Makins A. Postpartum contraception: feasibility of providing postpartum family planning counselling and immediate Postpartum Intra Uterine Device (PPIUD) services in low and middle-income countries. Coventry: University of Warwick, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JT, Tsai JL, Tsou TS, et al. Effectiveness of a theory‑based postpartum sexual health education program on women’s contraceptive use: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2011; 84: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lopez LM, Hiller JE, Grimes DA. Education for contraceptive use by women after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 20: CD001863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jambola ET, Gelagay AA, Belew AK, et al. Early resumption of sexual intercourse and its associated factors among postpartum women in western ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health 2020: 381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nkwabong E, Ilue EE, Nana Njamen T. Factors associated with the resumption of sexual intercourse before the scheduled six-week postpartum visit. Trop Doct 2019; 49(4): 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151(4): W-65–W-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho AT, Huynh KP, Jacho-Chávez DT, et al. Data science in Stata 16: Frames, lasso, and Python integration. J Stat Softw 2021; 98: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21(11): 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54(10): 1046–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eliason SK, Bockarie AS, Eliason C. Postpartum fertility behaviours and contraceptive use among women in rural Ghana. Contracept Reprod Med 2018; 3(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mekonnen BD. Factors associated with early resumption of sexual intercourse among women during extended postpartum period in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Contracept Reprod Med 2020; 5: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edosa Dirirsa D, Awol Salo M, Eticha TR, et al. Return of sexual activity within six weeks of childbirth among married women attending postpartum clinic of a teaching hospital in Ethiopia. Front Med 2022; 9: 865872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alum AC, Kizza IB, Osingada CP, et al. Factors associated with early resumption of sexual intercourse among postnatal women in Uganda. Reprod Health 2015; 12(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Owonikoko KM, Adeoye AG, Tijani AM, et al. Determinants of resumption of vaginal intercourse in puerperium period in Ogbomoso: consideration for early use of contraceptives. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2014; 3(4): 1061–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gadisa TB, G/Michael MW, Reda MM, et al. Early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse and its associated risk factors among married postpartum women who visited public hospitals of Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2021; 16(3): e0247769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adanikin AI, Awoleke JO, Adeyiolu A, et al. Resumption of intercourse after childbirth in southwest Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2015; 20(4): 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Radziah M, Shamsuddin K, Jamsiah M, et al. Early resumption of sexual intercourse and its determinants among postpartum Iban mothers. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2(2): 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cleland J, Shah IH, Daniele M. Interventions to improve postpartum family planning in low -and middle-income countries: program implications and research priorities. Stud Fam Plann 2015; 46(4): 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sok C, Sanders JN, Saltzman HM, et al. Sexual behavior, satisfaction, and contraceptive use among postpartum women. J Midwifery Womens Health 2016; 61(2): 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhuang C, Li T, Li L. Resumption of sexual intercourse post partum and the utilisation of contraceptive methods in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019; 9(3): e026132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asmamaw DB, Belachew TB, Negash WD. Multilevel analysis of early resumption of sexual intercourse among postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from Demographic and Health Survey Data. BMC Public Health 2023; 23(1): 733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Triviño-Juárez JM, Romero-Ayuso D, Nieto-Pereda B, et al. Resumption of intercourse, self-reported decline in sexual intercourse and dyspareunia in women by mode of birth: a prospective follow-up study. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74(3): 637–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kunwar S, Faridi MMA, Singh S, et al. Pattern and determinants of breast feeding and contraceptive practices among mothers within six months postpartum. Biosci Trends 2010; 4(4): 186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rowland M, Foxcroft L, Hopman WM, et al. Breastfeeding and sexuality immediately post partum. Can Fam Physician 2005; 51(10): 1366–1367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knutson AJ, Boyd SS, Long JB, et al. Early resumption of sexual intercourse after first childbirth and unintended pregnancy within six months. Womens Health Issues 2022; 32(1): 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet 1991; 338(8760): 131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salih MA, Murshid WR, Mohamed AG, et al. Risk factors for neural tube defects in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia: Case-control study. Sudan J Paediatr 2014; 14(2): 49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leeman LM, Rogers RG. Sex after childbirth: postpartum sexual function. Obstet Gynecol 2012; 119(3): 647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rzońca E, Iwanowicz-Palus G, Lenkiewicz E. Factors affecting sexual activity of women after child-birth. J Public Health Nurs Med Rescue 2016; 2016: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alimi R, Marvi N, Azmoude E, et al. Sexual function after childbirth: a meta-analysis based on mode of delivery. Women & Health 2023; 63: 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shabangu Z, Madiba S. The role of culture in maintaining post-partum sexual abstinence of Swazi women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16(14): 2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sehhatie F, Malakouti J, Mirghafourvand M, et al. Sexual function and its relationship to general health in postpartum women. J Womens Health Issues Care 2016; 5(1): 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455057241302303 for Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Habtamu Gebrehana Belay, Enyew Dagnew Yehuala, Simegnew Asmer Getie, Alemu Degu Ayele, Tigist Seid Yimer, Besfat Berihun Erega, Wassie Yazie Ferede, Mulugeta Dile Worke and Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie in Women’s Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-whe-10.1177_17455057241302303 for Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Habtamu Gebrehana Belay, Enyew Dagnew Yehuala, Simegnew Asmer Getie, Alemu Degu Ayele, Tigist Seid Yimer, Besfat Berihun Erega, Wassie Yazie Ferede, Mulugeta Dile Worke and Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie in Women’s Health

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-3-whe-10.1177_17455057241302303 for Determinants of early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis by Habtamu Gebrehana Belay, Enyew Dagnew Yehuala, Simegnew Asmer Getie, Alemu Degu Ayele, Tigist Seid Yimer, Besfat Berihun Erega, Wassie Yazie Ferede, Mulugeta Dile Worke and Gedefaye Nibret Mihretie in Women’s Health