Abstract

Dental anxiety usually stands in the way of obtaining adequate dental treatment, and the dental setting and team are considered factors that may affect dental anxiety. Many cross-sectional studies have indicated that dentally anxious children prefer their dentist to wear friendly attire rather than a conventional white coat, but no clinical trial has detected the effect of wearing a child’s friendly attire on anxiety levels among young patients. A total of 120 children were enrolled in this study and divided into four groups in which the dentists wore either friendly attire or white coat in the reception and treatment areas. Anxiety and pain were assessed while the patients received a dental injection. A statistically significant decrease in anxiety levels was observed in the 1st group compared with the other three groups after dental infiltration into the maxilla. The pain scores were significantly lower in the 1st group, whereas the control group patients scored the highest scores. A child’s friendly attire can help dentists build positive relationships with young patients and help reduce their anxiety.

Keywords: Friendly attire, White coat, Anxiety, Pain, Pediatric dentistry

Subject terms: Dentistry, Paediatric research, Psychology

Introduction

Dental anxiety “DA” is a reaction to an unknown risk for the patient, causing a state of fear that something serious is about to happen during dental treatment, which is often linked to a sense of loss of control1. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Mangalekar et al., dental anxiety is a prevalent issue affecting individuals of all ages worldwide2. As the prevalence of dental anxiety in pediatric patients is estimated to be between 5.7 and 20.2%, with multiple factors playing a crucial role in its prevalence3.

These factors are usually divided into external (past dental experiences, modeling, indirect experiences and wrong information) and internal factors (general anxiety, gender and age)4. While the factors influencing dental anxiety are varied, the appearance of the dentist’s attire may play a role in fear and anxiety4, as children anticipate an expectation of the dentist on the basis of their appearance, movements, and gestures during the first visit, even before any verbal communication takes place. In this context, professional appearance and attire could be important, as they may influence the development of the dentist‒patient relationship5.

Many studies have been conducted to observe children’s preferences for the dentist’s attire and its link to dental anxiety. Çubukçu and Çelik revealed that white dental attire and past dental experiences can influence the level of dental anxiety in primary school children6. Yahyaoglu et al. highlighted a correlation between children’s preferences for the dentist’s appearance and their levels of dental anxiety. Most children who chose colorful and patterned attire were classified as anxious. This choice was attributed to the attire acting as a distraction during treatment7. Additionally, Karmakar et al. demonstrated the impact of a dentist’s attire color on children’s anxiety levels and heart rate. yellow, blue, pink, and purple colors were shown to lower the heart rate and reduce anxiety in children during treatment. In contrast, when a dentist wore black or red, the child’s heart rate and anxiety levels increased8.

Oliviera et al. performed a systematic review and revealed variability in patient preferences for the dentist’s attire, which was attributed to cultural differences across the surveyed populations. According to the meta-analysis, there was no significant difference between patients’ preferences for traditional white coat and child-friendly attire. However, the studies included in the review highlighted that age plays an important role in this preference. Moreover, all the studies in the review focused on the relationship between anxiety levels and the child’s choice of the dentist’s attire. Additionally, it was noted that children with no prior dental experience were more likely to choose colorful attire9.

Noticeably, all observational studies were conducted as surveys with pictures of the attires listed in questionnaires, but none have examined the effects of dentists’ nonconventional attire on anxiety and pain levels among children while experiencing anxiety in the dental setting, even though this effect was evaluated and addressed later in pediatric clinics and hospitals as the clown doctor intervention.

This intervention has been found to be effective in managing anxiety and pain in young children by changing the stereotypical image of the medical staff in hospitals and using the appearance of a clown as a distraction during various medical procedures that may cause pain, such as venipuncture10,11. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effect of the dentist’s friendly attire on reducing anxiety and pain among children after receiving anesthetic injection, which is considered one of the main anxiety = evoking situations in the dental setting.

The null hypothesis: child-friendly dental attire does not reduce anxiety and pain levels in children who received dental anesthesia injection for the first time.

Methods and materials

Ethical approval

This study was registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06122883) (08/11/2023). Ethical approval for this study was obtained (IRB No. UDDS-4066-15082022) from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Dentistry, Damascus University. The study was conducted in accordance with the principals stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Parents/guardians were informed about the objectives and procedures of the study and authorized their children’s participation by signing an informed consent form. The current study was conducted in the Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Damascus University, from January 2023 until December 2023 to evaluate the effect of friendly attire on dental anxiety and pain after dental injections among children visiting dental offices in comparison with conventional white attire.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined via G-Power 3.1 statistical software after the effect size was calculated via a similar study in the medical literature11. The significance level of p was set at 0.05, and the study power was 0.95, resulting in a sample size of 88 children. After an attrition rate of 5% was calculated, the sample size was increased to 120 children to avoid drop out.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A total of 120 children visiting the department to receive pulpotomy treatment were included in the study. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Children between the ages of 6 and 10 years were eligible if they required a pulpotomy procedure in their maxillary molars. Additionally, the participants had not undergone any previous dental treatments. Only children who received a positive rating according to the Frankl Rating Scale, which assesses cooperative behavior, were included. Moreover, no sedative medications were administered to the children within three hours before the dental visit. Children with communication disabilities and those who were referred to the department due to severe dental pain were excluded from the study.

Randomization

After informed consent was obtained from the patients’ guardians, 60 male/60 female children were randomly assigned to one of the research groups by www.randomizer.org. Each participant was assigned a random number. The participants were subsequently randomly distributed into four groups via the block randomization method designed via the online service www.randomiation.com, which randomly distributes participants into four random permuted blocks, each containing 30 participants with an allocation ratio of 1:1:1:1. To achieve allocation concealment, randomization and allocation were performed before the commencement of the trial by a third party (a research student unaware of the study details). The operator conducting the trial met the participants for the first time in the operating room after they were enrolled and assigned a group.

Study groups

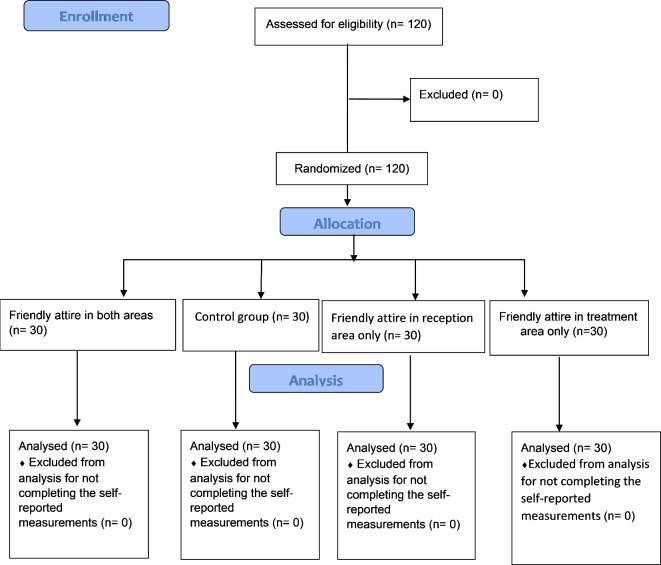

A 4-arms parallel study was conducted according to a CONSORT flowchart (Fig. 1). Children were assigned to 4 groups:

Group A: buccal and palatal infiltrations were administered with basic behavior guidance techniques while the dentist wearing friendly attire in the reception area and treatment room (Fig. 2).

Group B: buccal and palatal infiltrations were administered with basic behavior guidance techniques while the dentist wearing conventional attire in the treatment room after meeting the child in the reception area while wearing the friendly attire.

Group C: buccal and palatal infiltrations were administered with basic behavior guidance techniques while the dentist wearing friendly attire in the treatment room after meeting the child in the reception area while wearing the conventional attire.

Group D (Control group): buccal and palatal infiltrations were administered with basic behavior guidance techniques while the dentist wearing conventional attire in the reception area and treatment room.

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram.

Fig. 2.

Child-friendly attire.

The intervention

First, the dental setting was set the same way in all four groups: the walls were painted with a neutral color (baby blue), the reception area contained four chairs and a table colored light brown, and the dental office contained a light blue dental chair and cabins of the same color. After being seated in the dental chair, a 20% benzocaine gel was applied at the injection site prior to anesthesia for 1 min, and then a 1:80,000 lidocaine infiltration injection was administered in the maxillary arch.

Outcome measurements

This study evaluated the effect of dental attire on children’s anxiety and pain after receiving dental anesthesia in order to complete one of the most common dental treatments in pediatric dentistry (Pulpotomy). Pain and anxiety levels were evaluated before and during buccal and palatal infiltration using five scales.

Children’s state anxiety was assessed by the child anxiety questionnaire developed by Nilson et al.12, a driven tool from the state-trait anxiety scale that matches children’s cognitive abilities, as children give their response based on 4 facial expressions, one at a time, and then choose between three steps of how much the facial expression represent their feelings (i.e., a little, some and a lot). This accumulative scale was used to measure dental anxiety before and after treatment; scores ranging from 4 to 6 indicated no anxiety or mild anxiety, whereas scores ranging from 7 to 9 indicated moderate anxiety, with scores ranging from 10 to 12 indicating severe anxiety or phobia.

For dental anxiety, the Children Fear Scale was used to assess pre- and postoperative fear among patients undergoing painful medical procedures13. This is a self-reported assessment tool consisting of 5 faces representing different levels of fear, with 0 indicating no fear and 4 indicating the worst feeling of fear.

Both scales were used three times by the dentist who administrated the anesthesia: once the patient arrived at the reception area (T1), after the patient was seated in the dental chair (T2) and finally after receiving dental anesthesia (T3).

Additionally, changes in the physiological pulse rate were recorded at three different times during the study using finger pulse oximeter: the 1st time was 5 min after the patient was seated in the reception area, the 2nd time was 5 min after the patient was seated in the treatment area, and the 3rd time was 5 min after the dental injection.

To measure pain, the child was asked to choose a face from the Wong-Baker scale that matched his feelings after receiving the injection.

Children’s behavior during the administration of local anesthesia was recorded on video using a mobile phone camera attached to the dental chair (Shaomi redmi note 11 pro plus©) and was subsequently assessed by two external observers according to the Faces-Legs-Activity-cry-consolability scale (FLACC).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS 22, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

One-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of differences in pulse rate changes between groups, while the Wong-Baker, CFS, CAQ, and FLACC scores were compared with the Kruskal‒Wallis test. Bonferroni and Mann‒Whitney U tests were applied for multiple-dimensional comparisons to identify significant differences between two groups.

Independent t tests were used to compare pulse rate changes between the sexes, and the Mann‒Whitney test was used to compare CAQ, CFS, FLACC and Wong Baker scores between the sexes.

Results

One hundred and twenty patients were enrolled in this study, and the demographic characteristics of the groups are summarized in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found in terms of sex or age between the groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample description: one-way ANOVA test used for age comparisons, and the Kruskal‒Wallis test was used for sex comparisons.

| Variable | 1st group | 2nd group | 3rd group | 4th group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 8 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 0.530 |

| Gender, male (n, %) | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | 1.000 |

State anxiety

A statistically significant difference was found between groups in CAQ scores at T3 (p = 0.042), whereas no difference was detected at T1 (p = 0.077) or T2 (p = 0.074) between groups (Table 2) indicating that pretreatment anxiety levels did not differ between the reception area and treatment area. Compared with the control group, the 1st group presented a statistically significant decrease in anxiety levels after dental injection (Table 2).

Table 2.

CAQ mean scores recorded in the reception area and treatment area before and after surgery.

| Caq mean score | 1st group | 2nd group | 3rd group | 4th group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 5.37 | 4.70 | 4.87 | 5.63 | 0.077 |

| T2 | 5.37 | 4.70 | 4.80 | 5.63 | 0.074 |

| T3 | 4.50 | 4.60 | 4.57 | 5.43 | 0.042* |

The Kruskal‒Wallis test was used to detect changes in anxiety scores before and after injection between groups. *The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Dental anxiety

No significant difference was found between the groups in terms of CFS scores at T1 (p = 0.696), T2 (p = 0.638) or T3 (p = 0.063), with almost 95% of the enrolled patients having mild dental anxiety. Intragroup comparisons revealed a decreased level of fear among patients in the 1st group after dental injection compared with preoperatively (P = 0.014) (P = 0.020) (Table 3).

Table 3.

CFS score frequencies.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1st group | 11 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 19 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2nd group | 13 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3rd group | 12 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Control group | 12 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| P value | 0.696 | 0.638 | 0.063 | ||||||||||||

The Kruskal‒Wallis test was used to detect changes in fear scores before and after injection between groups. *The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

elf-reported pain (Wong-Baker) and disruptive behavior (FLACC)

The patient-reported pain score (wong-baker) did not differ significantly between the groups (p = 0.073). For FLACC scores, a statistically significant difference was detected between groups (p = 0.000) (Table 4). The Mann‒Whitney test revealed that patients in the 1st group scored the lowest scores. Indicating that they were most comfortable during the procedure, followed by patients in the 2nd and 3rd groups (p = 0.000), with control group patients feeling uncomfortable the most (Table 5).

Table 4.

Groupwise comparison of the mean FLACC score and the interquartile range of the W-B pain scale score.

| 1st group | 2nd group | 3rd group | Control group | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flacc media | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–4) | 0.000 |

| n (interquartile range) Mean ± standard deviation | 0.040 ± 0.563 | 0.93 ± 0.828 | 0.87 ± 0.730 | 1.50 ± 0.861 | * |

| Wong Baker median (interquartile range) | 0 (0–2) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 0.073 |

*The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Table 5.

Mann‒Whitney test for multiple-dimensional comparisons between every two groups with respect to the FLACC scale.

| Group | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FLACC Scores | 1st group | 2nd group | 0.008* |

| 3rd group | 0.010* | ||

| Control group | 0.000* | ||

| 2nd group | 3rd group | 0.836 | |

| Control group | 0.013* | ||

| 3rd group | Control group | 0.005* | |

*The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Physiological parameters

There was a statistically significant difference in pulse rate measurements at T3 compared with those at T1 and T2 (p = 0.000) (P = 0.000). The pulse rate was significantly lower in the 1st group than in the other three groups after dental injection, whereas no differences in pulse rate measured at T1 or T2 were detected between the groups (p = 0.070).

Intragroup comparisons revealed a significantly increased pulse rate in both male and female patients in the control group and 2nd group after dental injection (Table 6).

Table 6.

One‐way ANOVA was used to compare the mean pulse rates recorded in the reception area and treatment area before and after surgery between the groups.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P vlaue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st group | 99.07 ± 12.029 | 100.23 ± 13.526 | 96.47 ± 13.957 | 0.081 |

| 2nd group | 94.70 ± 10.343 | 93.90 ± 10.240 | 98.77 ± 10.088 | 0.034* |

| 3rd group | 95.80 ± 11.775 | 95.27 ± 12.418 | 98.33 ± 12.513 | 0.145 |

| Control group | 97.70 ± 10.600 | 95.30 ± 12.183 | 104.13 ± 10.126 | 0.027* |

*The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Comparison of anxiety and pain scores between males and females

No statistically significant difference was found between males and females in CFS, CAQ, Wong-Baker, and FLACC scores or in pulse rate changes (Tables 7, 8).

Table 7.

Independent t test used for mean score comparisons of pulse rates recorded in the reception area and treatment area before and post-operative between sexes.

| Sex | N | Mean | Std. deviation | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse rate 1 | Male | 60 | 95.42 | 9.757 | 0.064 |

| Female | 60 | 97.02 | 13.195 | ||

| Pulse rate 2 | Male | 60 | 96.13 | 11.242 | 0.145 |

| Female | 60 | 97.42 | 12.535 | ||

| Pulse rate 3 | Male | 60 | 99.08 | 12.262 | 0.981 |

| Female | 60 | 99.77 | 11.794 |

*The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Table 8.

Mann‒Whitney test used for multiple-dimensional comparisons between genders with respect to the CFS, CAQ, WB, and FLACC scales.

| Sex | N | Mean rank | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caq | Male | 60 | 59.04 | 0.624 |

| Female | 60 | 61.96 | ||

| Caq 2 | Male | 60 | 59.01 | 0.616 |

| Female | 60 | 61.99 | ||

| Caq 3 | Male | 60 | 58.69 | 0.525 |

| Female | 60 | 62.31 | ||

| Cfs | Male | 60 | 57.75 | 0.349 |

| Female | 60 | 63.25 | ||

| Cfs 2 | Male | 60 | 57.38 | 0.287 |

| Female | 60 | 63.62 | ||

| Cfs 3 | Male | 60 | 59.04 | 0.606 |

| Female | 60 | 61.96 | ||

| Wong-baker | Male | 60 | 61.58 | 0.701 |

| Female | 60 | 59.42 | ||

| flacc | Male | 60 | 59.57 | 0.753 |

| Female | 60 | 61.43 |

*The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Discussion

Several studies have indicated that a complex set of factors in the dental office plays a major role in developing and maintaining dental anxiety14. Children mostly link their previous painful dental experiences during any dental procedure to the dental team in the clinic; thus, the dentist becomes a stimulus of dental fear and anxiety to the patient15.

The present randomized clinical study analyzed the effects of friendly dental attire, which is considered an anxiety-evoking fator, on children’s anxiety levels when they receive a dental injection.

School-aged children were included in the study because they can express their emotions and report them more adequately than younger children do16.

Rachman stated that the development of anxious responses in children occurs either directly through conditioning or indirectly through modeling and information received, and subsequent studies documented that these confounding factors and the way children precept the dentist are significant contributors to child dental anxiety17.

This study revealed a decrease in CAQ scores in the 1st group (FABA) after dental injection compared with the three other groups, which could be attributed to the change in the child’s perception of the dentist’s attire; nevertheless, using a child-friendly color in the dental environment could enhance a positive attitude toward dental treatment, as young patients can connect colors to their emotional responses18. In the present study, the pretreatment anxiety levels did not differ significantly between the reception area and treatment area, as both areas were painted blue and had the same drawings on the walls. Moreover, Lin et al. reported an association between patients’ dental anxiety and their state anxiety and reported that dental anxiety is a significant predictor of expected pain and pain during treatment, whereas state anxiety can only predict expected pain19, in accordance with previous findings. Dental fear and anxiety and state anxiety were measured in this study via a child anxiety questionnaire, and a child fear scale as a pictorial scale is easier to interpret by children from different mental stages, which has advantages over other types of scales13.

Additionally, a statistically significant decrease in heart rate was recorded in the 1st group (FABA) after receiving the injection, indicating a reduced anxiety level in the 1st group of patients, as anxiety interferes with the pulse rate and other physiological parameters17. Anxiety can induce a response in the sympathetic nervous system, leading to changes in the cardiovascular system20.

In terms of pain perception, children in the 1st group (FABA) were more relaxed and felt less pain as a consequence of decreased anxiety, whereas controlling a patient’s emotional behavior and anxiety can increase the pain threshold, which eventually reduces pain perception18,21. The previous findings refute the null hypothesis and confirms the effect of child’s friendly dental attire on reducing anxiety levels among children receiving dental injection for the first time, which lead to a decreased pain level, resulting in a better experience for them in the dental setting. This result was in accordance with Meiri et al.11 and Javed et al.10 who confirmed the effect of changing child perception on doctors in reducing anxiety levels upon operating painful medical procedures. Overall, this study is one of few that has highlighted the crucial role of children’s perception of the dentist attire in modifying their anxiety in the dental office by exposing them to unconventional attires.

However, anxiety levels did not differ according to sex. This finding may be attributed to the complex nature of dental anxiety, which results from the interaction of multiple factors. Individual experiences and perceptions of dental care appear to have a greater influence than gender does, as dental anxiety is more prominently manifested through personal encounters rather than inherent gender characteristics22. This was in accordance with23,24. No difference was found in the degree of dental anxiety levels between males and females. Also the current study revealed no statistically significant difference in recorded pain levels between males and females. Pain assessment is related to the patient’s pain tolerance and pain threshold, both of which are influenced by various physical and psychosocial factors25. Additionally, a cohort study by Malmborg and colleagues demonstrated that pain levels in children are similar regardless of sex, despite physical differences. The study highlighted several factors influencing the pain experience, such as health-related quality of life and other psychological factors, which complicate the understanding of the role of sex in pain tolerance and assessment26.

A limitation to the study would be the dentist’s gender which could have played the role of confounding factor affecting the child’s perception of the dentist, another limitation would be the short period in which the child was exposed to the friendly attire, as it can be a disorienting factor to the child expectation of the whole dental treatment procedure. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine the effect of dentist’s gender on children’s anxiety levels and to evaluate the prolonged effect of child-friendly attire on whether the child’s anxiety levels or perceptions of the dentist persist over time or affect their future dental visits with different dental procedures.

Conclusion

In light of the previously mentioned limitations, this study indicates that altering a child’s perception of dental attire can reduce the anxiety and pain level experienced by the child while receiving a dental injection for the first time in the dental setting, this finding can improve children’s experience in the dental office and help establish a good patient-doctor relationship.

Author contributions

B.J. conception and design of the research, conducting the clinical process, and article writing; A.D. collecting data, and article writing; A.J. data analysis and interpretation, and article reviewing; L.M. research supervision, article revising, M.S. research supervision, article revising, A.D. study design and article review. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Klingberg, G. & Broberg, A. G. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behavior management problems in children and adolescents: A review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int. J. Pediatr. Dent.17(6), 391–406 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangalekar, S. B. et al. Dental anxiety scales used in pediatric dentistry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bangladesh J. Med. Sci.22, 117–126 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grisolia, B. M. et al. Prevalence of dental anxiety in children and adolescents globally: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Int. J. Pediatr. Dent.31(2), 168–183 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuscu, O. O., Caglar, E., Kayabasoglu, N. & Sandalli, N. Preferences of dentist’s attire in a group of Istanbul school children related with dental anxiety. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent.10(1), 38–41 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kastelic, D. R., Volpato, L. E., de Campos Neves, A. T., Aranha, A. M. & Martins, C. C. Do children and adolescents prefer pediatric attire over white attire during dental appointments? A meta-analysis of prevalence data. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent.14(1), 14 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Çubukçu, Ç. E. & Çelik, Z. C. Patterns of dental anxiety in primary schoolers attending oral health education program. J. Contemp. Med.13(2), 331–334 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yahyaoglu, O., Baygin, O., Yahyaoglu, G. & Tuzuner, T. Effect of dentists’ appearance related with dental fear and caries astatus in 6–12 years old children. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent.42(4), 262–268 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karmakar, S., Mathur, S. & Sachdev, V. A game of colours, changing emotions in children: A pilot study. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent.20, 377–381 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira, L. B. et al. Children’s perceptions of dentist’s attire and environment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent.13(6), 700–726 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javed, T. et al. Medical clowning: a cost-effective way to reduce stress among children undergoing invasive procedures. Cureus13(10), 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meiri, N., Ankri, A., Hamad-Saied, M., Konopnicki, M. & Pillar, G. The effect of medical clowning on reducing pain, crying, and anxiety in children aged 2–10 years old undergoing venous blood drawing—A randomized controlled study. Euro. J. Pediatr.175, 373–379 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia de Avila, M. A. et al. Children’s anxiety and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study using the children’s anxiety questionnaire and the numerical rating scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health17(16), 5757 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMurtry, C. M., Noel, M., Chambers, C. T. & McGrath, P. J. Children’s fear during procedural pain: Preliminary investigation of the Children’s Fear Scale. Health psychology30(6), 780 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seligman, L. D., Hovey, J. D., Chacon, K. & Ollendick, T. H. Dental anxiety: An understudied problem in youth. Clin. Psychol. Rev.55, 25–40 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avramova, N. Dental fear, anxiety, and phobia; causes, diagnostic criteria and the medical and social impact. J. Mind Med. Sci.9, 202–208 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira, A. I., Barros, L., Mendonça, D. & Muris, P. The relationships among parental anxiety, parenting, and children’s anxiety: The mediating effects of children’s cognitive vulnerabilities. J. Child Fam. Stud.23, 399–409 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sujatha, P. et al. Child dental patient’s anxiety and preference for dentist’s attire: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatric Dent.14(Suppl 2), S107 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umamaheshwari, N., Asokan, S. & Kumaran, T. S. Child friendly colors in a pediatric dental practice. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent.31(4), 225–228 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, C. S., Wu, S. Y. & Yi, C. A. Association between anxiety and pain in dental treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res.96(2), 153–162 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlad, R., Monea, M. & Mihai, A. A review of the current self-report measures for assessing children’s dental anxiety. Acta Med. Transilv25(1), 53–56 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alkanan, S. A. M., Alhaweri, H. S., Khalifa, G. A. & Ata, S. M. S. Dental pain perception and emotional changes: On the relationship between dental anxiety and olfaction. BMC Oral Health23(1), 175 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan, S. D. et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing various dental procedures. Bioinformation18(10), 982 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imamullah, A. Y., Utomo, R. B. & Supartinah, A. Comparison of dental anxiety levels measured using dental anxiety scale and GSR-psychoanalyzer in patients aged 6–8 years old. Odonto Dent. J.9(1), 1–11 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal, S., Chandak, M., Reche, A. & Singh, P. V. The prevalence of dental fear and its relationship to dental caries and gingival diseases among school children in Wardha. Cureus15(10), 1–9 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saraiva, L. H. A., Viana, L. D. S., Pereira, L. C., Costa, R. J. R. M. & Holsbach, D. R. Sex and age differences in sensory threshold for transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Fisioterapia em Movimento35, e35148 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malmborg, J. S. et al. Associations between pain, health, and lifestyle factors in 10-year-old boys and girls from a Swedish birth cohort. BMC Pediatrics23(1), 328–333 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.